4 The Information Technology

and Management Infrastructure

Strategy

Globalization and information

management strategies

1 Introduction

Recently, the globalization of competition has become the rule rather than the exception for a number of industries.39 To compete effectively, at home or globally, firms often must coordinate their activities on a worldwide basis. Although many global firms have an explicit global business strategy, few have a corresponding strategy for managing information technology internationally. Many firms have information interchange protocols across their multinational organizational structures, but few have global information technology architectures. A global information management strategy is needed as a result of (1) industry globalization: the growing globalization trend in many industries and the associated reliance on information technologies for coordination and operation, and (2) national competitive posture: the aggregation of separate domestic strategies in individual countries that may contend with coordination. While Procter and Gamble contends with the need to address more effectively its global market in the branded packaged goods industry, Singapore requires improved coordination and control of trade documentation in order to compete more effectively in the cross-industry trade environment that is vital to the economic health of that nation. Each approach recognizes the growing information intensity in their expanding markets. Each in turn must meet the challenges brought about by the need for cross-cultural and cross-industry cooperation.

Globalization trends demand an evaluation of the skills portfolio that organizations require in order to participate effectively in their changing markets. Porter41 suggests that coordination among increasingly complex networks of activities dispersed worldwide is becoming a prime source of competitive advantage: global strategies frequently involve coordination with coalition partners as well as among a firm's own subsidiaries. The benefits associated with globalization of industries are not tied to countries’ policies and practice. Rather, they are associated with how the activities in the industry value chain are performed by the firm's worldwide systems. These systems involve partnerships31 with independent entities that involve information and management process interchange across legal organization boundaries, as well as across national boundaries.

For a global firm, the coordination concerns involve an analysis of how similar or linked activities are performed in different countries. Coordination31 involves the management of the exchange of information, goods, expertise, technology, and finances. Many business functions play a role in such coordination – logistics, order fulfilment, financial, etc. Coordination involves sharing and use, by different facilities, of information about the activities within the firm's value chain.30 In global industries, these skills permit a firm to (1) be flexible in responding to competitors in different countries and markets, (2) respond in one country (or region) to a change in another, (3) scan markets around the world, (4) transfer knowledge between units in different countries, (5) reduce costs, (6) enhance effectiveness, and (7) preserve diversity in final products and in production location. The innovations in information technology (IT) in the past two decades have greatly reduced coordination costs by reducing both the time and cost of communicating information. Market and product innovation often involves coordination and partnership across a diverse set of organizational and geographically dispersed entities. Several studies26,27,38,42 suggest ways in which companies/nations achieve competitive advantage through innovation.

Organizations must begin to manage the evolution of a global IT architecture that forms an infrastructure for the coordination needs of a global management team. The country-centered, multinational firm will give way to truly global organizations that will carry little national identity.49,50 It is a major challenge to general management to build and manage the technical infrastructure that supports a unique global enterprise culture. This chapter deals with issues that arise in the evolution of a global business strategy and its alignment with the evolving global IT strategy.

Below we present issues related to the radical changes taking place in both the global business environment and the IT environment, with changes in one area driving changes in the other. Section 2 describes changes taking place in the global business environment as a result of globalization. It highlights elements from previous research findings on the effects of globalization on the organizational strategies/structures and coordination/control strategies. Section 3 deals with the information technology dimension and addresses the issue of development of a global information systems (GIS) management strategy. The section emphasizes the need for ‘alignment’ of business and technological evolution as a result of the radical changes in the global business environment and technology. Section 4 summarizes and presents other challenges to senior managers that are emerging in the global business environment.

2 Globalization and changes in the business environment

Since the Second World War, a number of factors have changed the manner of competition in the global business community. The particular catalyst for globalization and for evolving patterns of international competition varies among industries. Among the causative factors are increased similarity in available infrastructure, distribution channels, and marketing approaches among countries, as well as a fluid global capital market that allows large flows of funds between countries. Additional causes include falling political and tariff barriers, a growing number of regional economic pacts that facilitate trade relations, and the increasing impact of the technological revolution in restructuring and integrating industries. Manufacturing issues associated with flexibility, labor cost differentials, and other factors also play a role in these market trends.

Widespread globalization is also evident in a number of industries that were once largely separate domestic industries, such as software, telecommunications, and services.9,32,40 In the decade of the 1990s, the political changes in the Soviet Union and the Eastern European countries, plus the evolution of the European Common Market toward a single European market without national borders or barriers,13 also have led to growing international competition. Other factors are changing the economic dynamics in the Pacific Rim area, with changes in Hong Kong, Japan, China and Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, and the reentry of certain nations to the global economic community (e.g. Vietnam).

Previous research indicates that significant changes have taken place in organizational strategies/structure during the 1980s because of ever-increasing global competition and growth in the communications and information-processing industry. Researchers in international business have pointed out that the structure of a global firm's value chain is the key to its strategy: its fit with the environmental requirements that determine economic performance.3,15,37,40 Another study found that, in successful global firms, organization structure and strategy are matched by selecting the most efficient or lowest cost structure that satisfies the information-processing requirements inherent in the strategy.12 That is, the firm's strategy and its information-processing requirements must be in alignment with the firm's organizational structure and information-processing capabilities. To understand changes in organizational designs for global forms, these changes are highlighted in relation to the changes in strategies.

2.1 Evolution of the global firm's strategy/structure

Global strategy is defined by Porter40 as strategy from which ‘a firm seeks to gain competitive advantage from its international presence through either a concentrated configuration of activities, or coordinating among dispersed activities, or both’. Configuration involves the location(s) in the world where each activity in the value chain is performed, it characterizes the organizational structure of a global firm. A global firm faces a number of options in both configuration and coordination for each activity in the value chain. As implied by these definitions, there is no one pattern of international competition, neither is there one type of global strategy.

Bartlett3,4 suggests that for a global firm value-chain activities are pulled together by two environmental forces: (1) national differentiation, i.e. diversity in individual country-markets; and (2) global integration, i.e. coordination among activities in various countries. For global firms, forces for integration and national differentiation can vary depending on their global strategies. Table 4.1 shows the evolution of the global firms’ strategy/structure and their coordination/control strategies as a result of globalization of competition. The vocabulary of Bartlett4 and Porter40 will be further used in our framework.

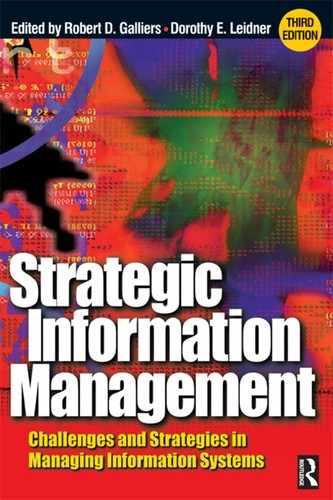

Under a multinational strategy, a firm might differentiate its products to meet local needs to respond to diverse interests. In such an approach, the firm might delegate considerable operating independence and strategic freedom to its foreign subsidiaries. Under this decentralized organizational structure, highly autonomous national companies are often managed as a portfolio of offshore investments rather than as a single international business. A subsidiary is focused on its local market. Coordination and control are achieved primarily through personal relationships between top corporate management and subsidiary managers than by written rules, procedures, or a formal organizational structure. Strategic decisions are decentralized and top management is involved mainly in monitoring the results of foreign operations. Figure 4.1 presents this organizational strategy/structure.

This model was the classic strategy/structure adopted by most European-based companies expanding before the Second World War. Examples include Unilever in branded packaged products, Phillips in consumer electronics, and ITT in telecommunications switching. However, much changed for European companies in the 1970s with the reduction of certain tariff barriers by the EEC* and with the entrance of both American and Japanese firms into local markets.

Table 4.1 Global business environment – strategy/structure and coordination control

Business strategy/structure |

Strategic management processes |

Tactical business processes |

Coordination and control processes |

Multinational/decentralized – federation |

Informal HQ-subsidiary relationships; strategic decisions are decentralized |

Mainly financial flows; capital out and dividends back |

Socialization; careful recruitment, development, and acculturation of key decision makers |

Global/centralized federation |

Tight central control of decisions, resources and information |

One-way flows of goods, resources and information |

Centralization; substantive decision making by senior management |

International/coordinated – federation |

Formal management planning and control systems allow tighter HQ – subsidiary linkages |

Assets, resources, responsibilities decentralized but controlled from HQ |

Formalization; formal systems, policies and standards to guide choice |

Transnational/integrated – network |

Complex process of coordination and cooperation in an environment of shared decision making |

Large flows of technology, finances, people, and information among interdependent units |

Co-opting; the entire portfolio of coordinating and control mechanisms |

Interorganizational/coordinated federation of business groups |

Share activities and gain competitive advantage by lowering costs and raising differentiation |

Vertical disaggregation of functions |

Formalization; multiple and flexible coordination and control functions |

In the machine lubricant industry, automotive motor oil tends toward a multinational competitive environment. Countries have different driving standards and regulations and regional weather conditions. Domestic firms tend to emerge as leaders (for example, Quaker State and Pennzoil in the United States). At the same time, multinationals, with country subsidies (such as Castrol, UK) become leaders in regional markets. In the lodging industry, many segments are multinational as a result of the fact that a majority of activities in the value chain are strongly tied to buyer location. Further, differences associated with national and regional preferences and lifestyle lead to few benefits from global coordination.

Figure 4.1 Multinational strategy with decentralized organizational structure

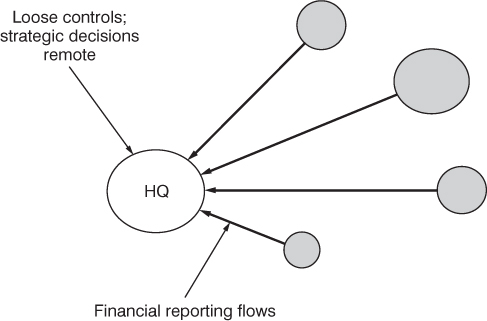

Under a pure global strategy, a firm may seek competitive advantage by capitalizing on the economies associated with standardized product design, global-scale manufacturing, and a centralized control of world-wide operation. The key parts of a firm's value-chain activities (typically product design or manufacturing) are geographically concentrated. They are either retained at the center, or they are centrally controlled. Under this centralized organizational structure, there are primarily one-way flows of goods, information, and resources from headquarters to subsidiaries; key strategic decisions for worldwide operations are made centrally by senior management. Figure 4.2 depicts this organizational strategy/structure.

This export-based strategy was/is typical in Japanese-based companies in the postwar years. They typically require highly coordinated activities among subsidiaries. Examples include KAO in branded packaged products, Matsushita in consumer electronics, NEC in telecommunications switching, and Toyota in the automobile industry. Toyota started by capitalizing on a tightly controlled operation that emphasized worldwide export of fairly standardized automobile models from global-scale plants in Toyota City, Japan. Lately, because of growing protectionist sentiments and lower factory costs in less-developed countries, Toyota (among others) has found it necessary to establish production sites in less-developed countries in order to sustain its competitive edge. The marine engine lubricant industry is a global industry that requires a global strategy. Ships move freely around the world and require that brand oil be available wherever they put into port. Brand reputations thus become global issues. Successful marine engine lubricant competitors (such as Shell, Exxon, and British Petroleum) are good examples of global enterprises.

Figure 4.2 Global strategy with centralized organizational structure

In the area of business-oriented luxury hotels, competitors differ from the majority of hotel accommodations and the competition is more global. Global competitors such as Hilton, Marriott, and Sheraton have a wide range of dispersed properties that employ common brand names, common format, common service standards, and worldwide reservation systems to gain marketing advantage in serving the highly mobile business travelers. Expectations of global standards for service and quality are high.

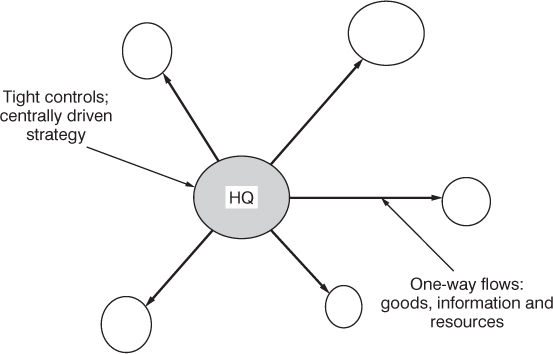

Under an international strategy, a firm transfers knowledge and expertise to overseas environments that are less advanced in technology and market development. Local subsidiaries are often free to adapt new strategies, products, processes, and/or ideas. Under this coordinated federation organizational structure, the subsidiaries’ dependence on the parent company for new processes and ideas requires a great deal more coordination and control by headquarters than under a classic multinational strategy. Figure 4.3 depicts this organizational strategy/structure.

This strategy/structure defines the managerial culture of many US-based companies. Examples include Procter and Gamble in branded packaged products, General Electric in consumer electronics, and Ericsson in telecommunications switching. These companies have a reputation for professional management that implies a willingness to delegate responsibility while retaining overall control through sophisticated systems and specialist corporate staffs. But, under this structure, international subsidiaries are more dependent on the transfer of knowledge and information than are subsidiaries under a multinational strategy; the parent company makes a greater use of formal systems and controls in its relations with subsidiaries.

Figure 4.3 International strategy with coordinated federation organizational structure

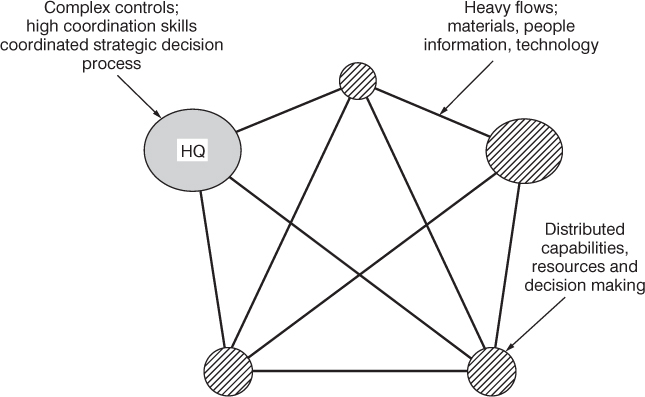

Under a transnational strategy, a firm coordinates a number of national operations while retaining the ability to respond to national interests and preferences. National subsidiaries are no longer viewed as the implementors of centrally-developed strategies. Each, however, is viewed as a source of ideas, capabilities, and knowledge that can be beneficial to the company as a whole. It is not unusual for companies to coordinate product development, marketing approaches, and overall competitive strategy across interdependent national units. Under this integrated network organizational structure, top managers are responsible for: (1) coordinating the development of strategic objectives and operating policies, (2) coordinating logistics among operating divisions, and (3) coordinating the flow of information among divisions.3 Figure 4.4 presents this organizational strategy/structure.

During the 1980s, forces of global competition required global firms to be more responsive nationally. As a result, the transnational strategies are being adopted by increasing numbers of global firms.3 This adoption is becoming necessary because of the need for worldwide coordination and integration of activities upstream in the value chain (e.g. inbound logistics, operations) and because of the need for a greater degree of national differentiation and responsiveness at the downstream end (e.g. marketing, sales, and services). For example, adoption of a transnational mode allowed companies such as Procter and Gamble, NEC, and Unilever to respond effectively to the new and complex demands of their international business environments. They were able to replace exports with local manufacture and to develop more locally differentiated products.3,9 In contrast, the inability to develop a similar organizational capability is seen by some to be a factor contributing to the strategic and competitive difficulties faced by companies such as ITT, GE, and KAO.

Special situations relate to another form of the coordinated federation organizational structure, interorganizational design, which is a particular form of the organizational framework represented in Figure 4.4. An inter-organizational design consists of two or more organizations that have chosen to cooperate by combining their strengths to overcome individual weaknesses.51 There are two modes of interorganizational design: equity and non-equity collaboration. Equity collaborations are seen in joint ventures, minority equity investments, and franchises. Non-equity collaborations are seen in forms of licensing arrangements, marketing and distribution agreements, and interorganizational systems.2,21,30,31 For example, in the airline industry, achieving the economies of scale in developing and managing a large-scale reservation system are now beyond the capacities of the medium-sized airlines. In Europe, two major coalitions have been created, the Amadeus Coalition and the Galileo Coalition. Software for Amadeus is built around System One, the computer reservation system for Continental and Eastern. Galileo makes use of United's software. Even the largest carriers have acknowledged their inability to manage a large-scale reservation system by themselves; they have joined coalitions.31

Figure 4.4 Transnational strategy with integrated-network organizational structure

Another highly visible example that demonstrates the notion of regional or national coordination in order to compete in a global market is the paper industry of Finland. The nineteen Finnish paper companies comprise a $3 billion industry that is heavily dependent on exports. Recently they determined that, to compete effectively in that service-oriented business, they must provide online electronic data interchange (EDI) interfaces with key customers and their sales offices. The Finnpap organization combined the efforts of the mill owners to develop an information system that reaches around the globe. The initial budget estimate of $40 million for five years has grown to an annual commitment of $10 million for the foreseeable future. None of the individual companies in the Finnish paper industry had the size, skills, and/or financial strength to create and deliver the world-class services necessary to compete against the large American, Canadian, and other global competitors. A regional cooperation was needed among the competitors in order to compete in the global market.

There has been a virtual explosion in the use of interorganizational designs for both global and domestic firms as a result of increased global competition during the 1980s. In 1983 alone, the number of domestic joint ventures announced in communications and information systems products and services industries exceeded the sum of all previously announced joint ventures in those sectors.17 Research suggests that interorganizational designs can lead to (1) ‘vertical disaggregation’ of functions (e.g. marketing, distribution) typically conducted within the boundaries of a single organization performed independently by the organizations within the network, (2) the use of ‘brokers,’ or structure-independent organizations, to link together the different organizational units into ‘business groups’ for performance of specific tasks, and (3) the substitution of ‘full disclosure information systems’ in traditional organizations for lengthy trust-building processes based on experience.36

2.2 Evolution of the global firm's coordination control strategies

Strategic control is considered to be the key element for the ‘integration’ of a firm's value-chain activities; it is defined as ‘the extent of influence that a head office has over a subsidiary concerning decisions that affect subsidiary strategy’.10 Previous research found that, as resources such as capital, technology, and management become vested in the subsidiaries, head offices cannot continue to rely on control over these resources as means of influencing subsidiary strategy.1,10,44 The nature of strategic control by the head office over its subsidiaries shifts with time; there is a need for new forms of administrative control mechanisms such as those offered through improved information management strategies.

In a study of nine large worldwide companies and by interviewing 236 managers both in corporate headquarters and in a number of different national subsidiaries, Bartlett and Ghoshal4 found that many companies had reached a coordination crisis by 1980. New competitive pressures were requiring the global firms to develop multiple strategic capabilities, even as other environment forces led them to reconfigure their historical organization structures. Many familiar means of coordination (e.g. socialization, centralization, and formalization – shown in Table 4.1) characteristically proved inadequate to this new challenge.

The study further reports that European companies began to see the power and simplicity of more centralized coordination of subsidiaries. The Japanese increasingly adopted more formal systems, routines, and policies to supplement their traditional time-consuming, case-by-case negotiations. American managers took new interest in shaping and managing the previously ignored informal processes and value systems in their firms. The study also found that the challenge for many global firms was not to find the organizational structure that provided the best fit with their global strategies, but to build and manage the appropriate decision-making processes that can respond to multiple changing environmental demands. Furthermore, because of evolving global strategies from multinational to transnational, decision making is no longer concentrated at corporate headquarters. Today's global firm must be able to carry a great deal of complex information to diverse locations in its integrated network of operations.

As we have seen, research on international business suggests that globalization has caused a change in the coordination/control needs of global firms. As a result, new organizational designs are created to meet new organizational coordination needs and to deal with increased organizational complexity and size. The traditional organizational designs18,29 such as functional, multidivisional, and matrix forms, are largely inappropriate for today's global firms.

Research further suggests that different organizational strategies/structures are necessary across products or businesses with diverse (global) environment demands. In response, there have been two relatively new trends in organizational strategies: (1) a shift from a multinational strategy with decentralized organizational structures to a transnational strategy and globally integrated networks of operations, and (2) a rapid proliferation of inter-organizational designs and structurally independent organizational units and business groups.

In short, the success in global competition depends largely on (1) a proper fit between an organization's business strategy and its structure, (2) an organization's ability to adapt its structure in order to balance the environmental forces of national differentiation and global integration for its value-chain activities, and (3) the manner of coordination/control of the organization's value-chain activities. As presented above, the globalization of competition and the evolving business environment suggest that the success of today's global firms’ business and its coordination/control strategies may be linked to a global information management strategy. In the following section, the roles and characteristics of global information systems (GIS) and their differences with traditional distributed data-processing systems are discussed. A global information system management strategy is proposed. The need for ‘alignment’ of the organization's business strategy/structure with its information system management strategy is emphasized as part of this strategy.

3 Global information systems

Due to the dramatic changes in IT, and the increased skills in organizations to deploy and exploit those advances, there are an increasing number of applications of IT by global firms in both service and manufacturing industries. The earliest were in international banking, airline, and credit authorization. However, during the 1980s, due to rapid improvements in communication and IT, more and more activities of global firms were coordinated using information systems. At the same time, patterns in the economies of IT development are changing.19,22,38 The existence or near completion of public national data networks and of public or quasi-public regional and international networks in virtually all developed (and a few developing) countries has resulted in rapid growth in data-service industries, e.g. data processing, software, information storage and retrieval, and telecommunications services.26,46

Today global firms not only rely on data-service industries and IT to speed up message transmission (e.g. for ordering, marketing, distribution, and invoicing), but also to improve the management of corporate systems by: (1) improving corporate functions such as financial control, strategic planning, and inventory control, and (2) changing the manner in which global firms actually engage in production (e.g. in manufacturing, R&D, design and engineering, CAD/CAM/CAE).46 Therefore, more and more of global firms’ mechanisms for planning, control and coordination, and reporting depend on information technology. According to the head of information systems at the $35 billion chemical giant, information systems will either be a facilitator or an inhibitor of globalization during the 1990s.35

A global information system (GIS) is a distributed data-processing system that crosses national boundaries.7 There are a number of differences between domestic distributed systems25 and GISs. Because GISs cross national boundaries, unlike domestic distributed systems, they are exposed to wide variations in business environments, availability of resources, and technological and regulatory environments. These are explained briefly below.

Business Environment. From the perspective of the home-base country, there are differences in language, culture, nationality, and professional management disciplines among subsidiary organizations. Due to differences in local management philosophy, business/technology planning responsibilities are often fragmented rather than focused in one budgetary area. Business/technology planning, monitoring, and control and coordination functions are often difficult and require unique management skills.24

Infrastructure. The predictability and stability of available infrastructure in a given country are major issues when making the country a hub for a global firm: ‘It is a fact of life that some countries are tougher to do business in than others.’8 Regional economic dependence on particular industry and cross-industry infrastructure may be informative. Singapore26 has provided, through TradeNet, a platform for fast, efficient trade document processing. Hong Kong,27 on the other hand, is still dealing with its unique position as the gateway to the People's Republic of China, and its historic ‘free port’ policies in developing its TradeLink platform. Lufthansa, Japan Airlines, Cathay Pacific, and other airlines are trying to pool their global IT infrastructure in order to deliver a global logistics system. At the same time, global banks are exploring the influence their IT architectures have on the portfolio of instruments they can offer on a global basis.37

Resource availability can vary due to import restrictions or to lack of local vendor support. Since few vendors provide worldwide service, many firms are limited in choice of vendors in a single project, because of operational risk. Finally, availability of telecommunications equipment/technology (e.g. LAN, private microwave, fiber optic, satellite earth stations, switching devices, and other technologies) varies among countries and geographic regions.

Regulatory Environments. Changes in government, economy, and social policy can lead to critical changes in the telecommunications regulations that pose serious constraints on the operation of GISs. The price and availability of service, and cross-border data-flow restrictions vary widely from one country to another.

The PTT (post, telephone, and telegraph) in most countries sets prices based on volume of traffic rather than based on fixed-cost leased facilities. By doing so, the PTT increases its own revenues and, at the same time, prevents global firms from exploiting economies of scale. The nature of the internal infrastructure systems may also influence the interest and ability to leverage regulation.38,49,50

There are regulations restricting usage of leased lines or import of hardware/software for GISs. These affect the GIS options possible in different countries: restrictions on connections between leased lines and public telephone networks, the use of dial-up data transmission, and the use of electronic mail systems for communications. It is not unusual for some companies to build their own ‘phone company’ in order to reduce dependence on government-run organizations.8 Hardware/software import policies also make local information processing uneconomical in some countries. For example, both Canada and Brazil have high duties on imported hardware, and there are software import valuation policies in France, Saudi Arabia, and Israel.6

Transborder Data Flow (TBDF) regulations, in part, govern the content of international data flows.5 Examples are requirements to process certain kinds of data and to maintain certain business records locally, and the fact that some countries don't mind data being ‘transmitted in’ but oppose interactive applications in which data are ‘transmitted out’. Although the major reasons for regulating the content of TBDF are privacy protection and economic and national security concerns, these regulations can adversely affect the economies of GISs by forcing global firms to decentralize their operations, increase operating costs, and/or prohibit certain applications.

Standards. International, national, and industry standards play a key role in permitting global firms to ‘leverage’ their systems development investment as much as possible. Telecommunication standards vary widely from one country to another concerning the technical details of connecting equipment and agreements on formats and procedures. However, the conversion of the world's telecommunications facilities into an integrated digital network (IDN) is well underway, and most observers agree that a worldwide integrated digital network and the integrated services digital network (ISDN) will soon become a reality.34,48 The challenge is not a problem of technology – the necessary technology already exists. Integration depends on creating the necessary standards and getting all countries to agree.

Telecommunications standards are set by various domestic governments or international agencies, and by major equipment vendors (e.g. IBM's System Network Architecture (SNA), Wang's Wangnet, Digital Equipment's DecNet, etc). There are also standards set by groups of firms within the same industry, such as SWIFT (Society for Worldwide International Funds Transfer) for international funds transfers and cash management, EDI (Electronic Data Interchange) for formatted business transactions such as purchase orders between companies (ANSI, EDIFACT, etc.),16 and SQL (Structured Query Language) as a common form of interface for coordinating data across many databases.

3.1 Global information management strategy

Table 4.2 shows the alternative information systems management strategy/structure as a result of the evolution in global business environment and technology. New information technologies are allowing closer integration of adjacent steps on the value-added chain through the development of electronic markets and electronic hierarchies.33 As that study reports, the overall effect of technology is the change of coordination mechanisms. This will result in an increase in the proportion of economic activities coordinated by markets rather than by hierarchies. This also supports and explains change in global firms’ strategies from multinational, global strategies to international (interorganizational), transnational strategies.

Table 4.2 Alignment of global and information management strategies

Business strategy/structure |

Coordination control strategy |

Coordination control mechanisms |

IS strategy structure |

Multinational decentralized – federation |

Socialization |

Hierarchies; managerial decisions determine the flow of materials and services |

Decentralization/standalone databases and processes |

Global/centralized – federation |

Centralization |

|

Centralization/centralized databases and processes |

International and interorganizational/coordinated federation |

Formalization |

Markets; market forces determine the flow of materials and services |

IOS/linked databases and processes |

Transnational integrated network |

Co-opting |

|

Integrated architecture/shared databases and processes |

The task of managing across corporate boundaries has much in common with that of managing across national borders. Managing strategic partnerships, coalitions, and alliances has forced managers to shift their thinking from the traditional task of controlling a hierarchy to managing a network.11,31,43 As discussed earlier, managers in transnational organizations must gather, exchange, and process large volumes of information; formal strategies/structures, cannot support such huge information-processing needs. Because of the widespread distribution of organizational units and the relative infrequency of direct contacts among those in disparate units in a transnational firm, top management has a better opportunity to shape relationships among managers simply by being able to influence the nature and frequency of contacts by using a proper information system management strategy.

The strategy should contain the senior management policy on corporate information systems architecture (ISA). Corporate ISA (1) provides a guide for systems development, (2) facilitates the integration and data sharing among applications, and (3) supports development of integrated, corporate systems that are based on a data resource with corporate-wide accessibility.19 Corporate ISA for a global firm is a high-level map of the information and technology requirements of a firm as a whole; it is composed of network, data, and application and technology architectures. In the international environment, the network and data architectures are generally considered to be the key enabling technologies because they are the highway systems for a wide range of traffic.24

A new GIS management strategy needs to address organizational structural issues related to coordination and configuration of value-chain activities, by proper ISA design. The key components of a GIS management strategy are (1) a centralized and/or coordinated business/technology strategy on establishing data communications architecture and standards, (2) a centralized and/or coordinated data management strategy for creation of corporate databases, and (3) alignment of global business and GIS management strategy. These are explained below.

3.1.1 Network management strategy and architecture

Network architecture describes where applications are executed, where databases are located, and what communications links are needed among locations. It also sets standards ensuring that all other ISA components are interrelated and working together. The architecture is important in providing standards for interconnecting very different systems instead of requiring commonality of systems. At present, the potential for network architecture is determined more often by vendors than by general industry or organizational standards.24

Architecture. Research on international business points out that the structure of a global firm's value chain is the key to its strategy; its fit with environmental requirements derives economic performance. However, the environments of GISs are external to their global firms and thus cannot be controlled. Services provided by GISs must be globally coordinated, integrated, standardized, and tailored to accommodate national differences and individual national markets.

Deciding on appropriate network architecture is a leading management and technology issue. Research in the global banking industry found that an international bank providing a wide range of global electronic wholesale banking services has some automated systems that need to be globally standardized (e.g. global balance reporting system), while others (e.g. global letter of credit system) need to be tailored to individual countries’ markets.37 The research also suggests that appropriate structure for GISs may vary for different product and service portfolios: uniform centralization/decentralization of strategy/structure may not be appropriate for all GIS applications. Further, the research found that international banks cannot expect to optimize the structure of environmentally diverse information systems with a symmetrical approach to GIS architecture, since any such approach may set limits on the product and service portfolios called for by the bank's global business strategy. An asymmetrical approach, structuring each system to suit the environmental needs of the service delivered, although more complex, can significantly improve international banks’ operational performance. Such an approach may, however, significantly increase coordination costs.

Standards. Use of standards is an important strategic move for most companies, since many of today's companies limit the number of intercompany formats they support. With the success in the development and adoption of global standards, in particular in narrow areas (e.g. EDIFACT), it is much harder to make standards mistakes than was possible several years ago. By using standards, companies can broaden their choice of trading partners in the future. Absence of uniform data and communications standards in international, national, and industry environments means that no single product can address more than a fraction of the hardware and communications protocols scattered throughout a firm.

Standards are often set by government rules and regulations, major computers and communications vendors, and/or cooperative arrangements within an industry. Regardless of how the standards are set, they are critical to the operations of GISs. Because standards are the key to connectivity of a set of heterogeneous systems, explicit senior management policy on standards is important to promote adoption and compliance. There should be one central policy regarding key technologies/standards (e.g. EDI, SQL). This policy should include a management agenda for understanding both standards and the standard-setting process within industry, national, and international environments.23 Such a central policy accomplishes several objectives, reducing cost, avoiding vendor viability, achieving economies of scale, reducing potential interface problems, and facilitating transborder data flow. Therefore, decisions about the components of network architectures and standards require a move toward centralized, corporate management coordination and control. However, decisions regarding adding traffic need decentralized planning; they require conformity by IS managers to data communications standards.

3.1.2 Data management strategy and architecture

Data architecture concerns the arrangement of databases within an organization. Although every organization that keeps data has a data architecture, in most organizations it is the result of evolution of application databases in its various departments and not the result of a well-planned data management strategy.14,45 Data management problems are amplified for large global firms with diverse product families. For a global firm with congested data highways, the problems of getting the right data in the right amount to the right people at the right time multiply as global markets emerge.8

Lack of a centralized information management strategy often causes corporate entities (e.g. customers and products) to have multiple attributes, coding schemes, and values across databases.14 This makes linkages or data sharing among value activities difficult at best; establishing linkages requires excessive time and human resources; costs and performance of other data-related activities within the value chain are affected. These factors make important performance and correlation data unavailable to top management for decision making, thereby creating important obstacles to the firm's competitive position and its future competitive advantage.

Strategy/Architecture. To increase coordination among a global firm's value-chain activities, its data architecture should be designed based on an integrated data management strategy. This strategy should mandate creation of a set of corporate databases derived from the firm's value-chain activities. A recent study has pointed out the significance of a firm's value-chain activities in deploying IT strategically;20 however, no specific information management strategy is proposed.

Corporate data is used by more than one functional area within the value-chain activities. In contrast, department data is often used mainly by departments within the functional area that comprises a value-chain activity. Corporate data is used by departments across functions.

Corporate databases should be based on business entities involved in value-chain activities rather than around individual applications. A firm must define (1) appropriate measures of performance for each value activity (e.g. sales volume by market by period), (2) corporate entities by which the performance is measured (e.g. product, package type), (3) relationships among the entities defined, (4) entities’ value sets, coding schemes, and attributes, (5) corporate databases derived from the entities, and (6) relationships among the corporate databases. For example, for a direct value-adding activity such as marketing and sales within a firm's value chain, the corporate databases may include: advertisement, brand, market, promotion, sales.

Given this data management strategy, corporate databases are defined independent of applications; they are accessible by all potential users. This data management strategy allows a firm's senior management to (1) integrate and coordinate information with the value-adding and support activities within the value chain, (2) identify significant trends in performance data, and (3) compare local activities to activities in other comparable locations.

This data management strategy creates an important advantage for a global firm, because activities used for the firm's strategic business planning are used to define the corporate databases. The critical establishment of linkage between strategic business planning and strategic information systems planning is possible when this strategy is used, because the activities that create value for the firm customers also create data the firm needs to operate. However, the strategy does not imply that all application databases should be replaced by corporate databases. Application databases should remain (directly or indirectly) as long as the applications exist; but there should be a disciplined flow of data among corporate, functional, and application databases.

3.1.3 Alignment of global business and GIS management strategy: a plan for action

One challenge facing management today is the necessity for the organization to align its business strategy/structure to its information systems management/development strategy. A proper design of critical linkages among a firm's value-chain activities results in an effective business design involving information technology and an improved coordination with coalition partners, as well as among a firm's own subsidiaries. Previous research has emphasized the benefits of establishing proper linkages between business-strategic planning and technology-strategic planning for an organization.22,28 Among these are proper strategic positioning of an organization, improvements in organizational effectiveness, efficiency and performance, and full exploitation of information technology investment.

Establishing the necessary alignment requires the involvement of and cooperation with both the senior business planner and the senior IS technology manager. This results in a new set of responsibilities and skills for both. For the senior business planner, new sets of responsibilities include (1) formal integration of the strategic business plan with the strategic IS plan, (2) examination of the business needs associated with a centralized and/or coordinated network, technology, and data management strategy, (3) review of the network architecture as a key enabling technology for the firm's competitive strategy and assessment of the impact of network alternatives on business strategy, (4) awareness of key technologies/standards and standard-setting processes at the industry, national, and international levels, (5) championing the rapidly expanding use of industry, national, and international standards.

For the senior information technology manager, new and critical responsibilities include (1) awareness of the firm's business challenges in the changing global environment and involvement in shaping the firm's leverage of information technology in its global business strategy, (2) preparing a systems development environment that recognizes the long-term company-wide perspective in a multi-regional and multi-cultural environment, (3) planning the development of the application portfolio on the basis of the firm's current business and its global strategic posture in the future, (4) making the ‘business purpose’ of the strategic systems development projects clear in a global business context, (5) selecting and recommending key technologies/standards for linking systems across geographic and cultural boundaries, (6) setting automation of linkages among the internal/external activities within the firm's value chain as goals and selling them to others, (7) designing corporate databases derived from the firm's value-chain activities, accounting for business cultural differences, and (8) facilitating corporate restructuring through the provision of flexibility in business services.

4 Summary and conclusions

Changes in technologies and market structures have shifted competition from national to a global scope. This has resulted in the need for new organizational strategies/structures. Traditional organizational designs are not appropriate for the new strategies, because they evolved in response to different competitive pressures. New organizational structures need to achieve both flexibility and coordination among the firm's diverse activities in the new international markets.

Globalization trends have resulted in a variety of organizational designs that have created both business and information management challenges. A global information systems (GIS) management strategy is required.

The key components of a GIS management strategy should include: (1) a centralized and/or coordinated business/technology strategy on establishing data communications infrastructure, architecture, and standards, (2) a centralized and/or coordinated data management strategy for design of corporate databases, and (3) alignment of global business and GIS management strategy. Such a GIS management strategy is appropriate today because it facilitates coordination among a firm's value-chain activities and among business units, and because it provides the firm with the flexibility and coordination necessary to deal effectively with changes in technologies and market structures. It also aligns information systems management strategy with corporate business strategy as it provides a foundation for designing information systems architecture (ISA).

In addition to the global enterprise's competitive posture, globalization also refers to the competitive posture of nations and city-states.26,27 The issues related to coordination and control in the global enterprise also invest the nation/state to review the alignment of its cross-industry competitive posture.31,42 It is incumbent on governments to seek appropriate levels of intervention in the business practices of the state that influence the state's competitive position in the global business community.

The challenges to general managers in the emerging global economic environment extend beyond the IT infrastructure. At the same time, with the information intensity in the markets (products, services, and channel systems) and the information intensity associated with coordination across geographic, cultural, and organizational barriers, global general managers will rely increasingly on information technologies to support their management processes. The proper alignment of the evolving global information management strategy and the global organizational strategy will be important to the positioning of the global firm in the global economic community.

References

1 Baliga, B. R. and Jaeger, A. M. Multinational corporations, control systems and delegation issues. Journal of International Business Studies, 15, 2 (Fall 1984), 25–40.

2 Barrett, S. and Konsynski, B. Interorganizational information sharing systems. MIS Quarterly, special issue (1982), 93–105.

3 Bartlett, C. A. and Ghoshal, S. Organizing for worldwide effectiveness: the transnational solution. California Management Review, 31, 1 (1988), 1–21.

4 Bartlett, C. A. and Ghoshal, S. Managing across Borders: The Transnational Solution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1989.

5 Basche, J. Regulating international data transmission: the impact on managing international business. Research report no. 852 from the Conference Board. New York, 1983.

6 Business Week. Special report on telecommunications: the global battle (October 1983).

7 Buss, M. Managing international information systems. Harvard Business Review, special series (1980).

8 Carlyle, R. E. Managing IS at multinationals. Datamation (March 1, 1988), 54–66.

9 Chandler, A. D. The evolution of modern global competition. In [39], 405–488.

10 Doz, Y. L. and Prahalad, C. K. Headquarters influence and strategic control in MNCs. Sloan Management Review (Fall 1981), 15–29.

11 Eccles, R. G. and Crane, D. B. Managing through networks in investment banking. California Management Review, 30 (Fall 1987), 176–195.

12 Engelhoff, W. Strategy and structure in multinational corporations: an information processing approach. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 3 (1982), 435–458.

13 Frenke, K. A. The European community and information technology. Communications of the ACM (special section the EC ’92), 33, 4 (1990), 404–412.

14 Goodhue, D. L., Quillard, J. A. and Rockart, J. F. Managing the data resource: a contingency perspective. MIS Quarterly, 12, 3 (September 1988), 372–391.

15 Ghoshal, S. and Noria, N. International differentiation within multinational corporations. Strategic Management Journal, 10, 4 (July/August 1989), 323–337.

16 Hansen, J. V. and Hill, N. C. Control and audit of electronic data interchange. MIS Quarterly, 13, 4 (December 1989), 403–413.

17 Harrigan, K. R. Strategies for Joint Ventures. Lexington, MA: 1985.

18 Huber, G. P. The nature and design of post industrial organization. Management Science, 30 (1984), 928–951.

19 Iramon, W. H. Information Systems Architecture. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1986.

20 Johnston, H. R. and Carrico, S. R. Developing capabilities to use information strategically. MIS Quarterly, 12, 1 (March 1988), 36–48.

21 Johnston, H. R. and Vitale, M. Creating competitive advantage with interorganizational information systems. MIS Quarterly, 12, 2 (June 1988), 152–165.

22 Karimi, J. Strategic planning for information systems: requirements and information engineering methods. Journal of Management Information Systems, 4, 4 (Spring 1988), 5–24.

23 Keen, P. G. An international perspective on managing information technologies. ICIT Briefing Paper no. 4101, 1987.

24 Keen, P. G. Competing in Time: Using Telecommunications for Competitive Advantage. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Co., 1988.

25 King, J. Centralized vs. decentralized options. Computing Surveys (December 1983).

26 King, J. and Konsynski, B. Singapore TradeNet: a tale of one city. NI191–009, Harvard Business School, 1990.

27 King, J. and Konsynski, B. Hong Kong TradeLink: news from the second city. N1–191–026. Harvard Business School, 1990.

28 King, W. R. Strategic planning for IS: the state of practice and research. MIS Quarterly, 9, 2 (June 1985), Editor's comment, vi–vii.

29 Knight, K. Matrix organization: a review. Journal of Management Studies, 13 (1976), 111–130.

30 Konsynski, B. and Warbelow, A. Cooperating to compete: modeling interorganizational interchange, Harvard Business School working paper 90–002, 1989.

31 Konsynski, B. and McFarlan, W. Information partnerships – shared data, shared scale. Harvard Business Review (September/October 1990), 114–120.

32 Lu, M. and Farrell, C. Software development: an international perspective. The Journal of Systems and Software, 9 (1989), 305–309.

33 Malone, T. W., Yates, J. and Benjamin, R. I. Electronic markets and electronic hierarchies. Communications of the AGM, 30, 6 (June 1987), 484–497.

34 Martin, J. and Leben, J. Principles of Data Communications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1988.

35 Mead, T. The IS innovator at DuPont. Datamation (April 15, 1990), 61–68.

36 Miles, R. E. and Snow, C. C. Organizations: new concepts for new forms. California Management Review, 28 (1986), 62–73.

37 Mookerjee, A. S. Global Electronic Wholesale Banking Delivery System Structure. PhD thesis, Harvard University, 1988.

38 O'Callaghan, R. and Konsynski, B. Banco Santander: el banco en casa, 9–189–185, Harvard Business School, 1989.

39 Porter, M. E. Competition in Global Industries. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1986.

40 Porter, M. E. Competition in global industries: a conceptual framework. In [39], 15–59.

41 Porter, M. E. From competitive advantage to corporate strategy. Harvard Business Review (May/June 1987), 43–59.

42 Porter, M. E. The competitive advantage of nations. Harvard Business Review (March/April 1990), 73–92.

43 Powell, W. Hybrid organizational arrangements. California Management Review, 30 (Fall 1987), 67–87.

44 Prahalad, C. K., and Doz, Y. L. An approach to strategic control in MNCs. Sloan Management Review(Summer 1981), 5–13.

45 Romero, V. Data Architecture: The Newsletter for Corporate Data Planners and Designers, 1, 1 (September/October 1988).

46 Sauvant, K. International transactions in services: the politics of transborder data flows. The Atwater Series on World Information Economy, I. Boulder: Westview Press, 1986.

47 Selig, G. J. A framework for multinational information systems planning. Information and Management, 5 (June 1982), 95–115.

48 Stallings, W. ISDN: An Introduction. New York: Macmillan, 1989.

49 Warbelow, A., Kokuryo, J. and Konsynski, B. Aucnet: TV auction network system. 9–190–001, Harvard Business School, 1989, p. 19.

50 Warbelow, A., Fjeldstad, O. and Konsynski, B. Bankenes Betalings-Sentral A/S: the Norwegian bank giro. N9–191–037, Harvard Business School, 1990, p.17.

51 Zammuto, R. Organization Design: Structure, Strategy, and Environment. The Dryden Press, forthcoming.

Copyright @ 1991 by M. E. Sharpe, Inc. Karimi, J. and Konsynski, B. R. (1991) Globalization and information management strategies. Journal of Management Information Systems, 7(4), Spring, 7–26. Reprinted with permission.

Questions for discussion

1 Evaluate the organizational strategies the authors present. What are the implications for IT architecture?

2 Do you agree with the major premise that ‘the globalization of competition and the evolving business environment suggest that the success of [a] global firms’ business and its coordination/control strategies may be linked to a global information management strategy’?

3 Will changes taking place in Europe (e.g. pan-European legislation, the introduction of the Euro) reduce the impact of some of the factors complicating international IS, such as the business environment, infrastructure, regulations, transborder dataflow, and standards?

4 The authors present a one-on-one alignment of IT strategy and organizational strategy. Is this realistic? Are there other effective alignments? How might effective alignment be achieved?

5 Assuming different stages of growth in different countries, what might be the appropriate role of the central IT group in a large multinational organization?

*The EEC was the forerunner to the European Union (EU)