7 An empirical study of user satisfaction with a health dialogue system designed for the Nigerian low-literate, computer-illiterate, and visually impaired

Abstract: The advent of the Internet has made this elaborate communication network a repository for many different kinds of information sharing. Among the information normally searched for on the Internet is health-based information. This information helps the consumers to carry out “self-care” (activities that contribute to maintaining a state of well-being); in so doing, it empowers them to initiate lifestyle changes and new regimens to maintain good health. However, this information on the Internet is primarily delivered in text format. Due to inadequate Internet access and the low level of literacy in Nigeria, vital health information is only available to a small percentage of the population. This chapter reports on the development, acceptability, and user satisfaction with a dialogue system providing health information about lassa fever, malaria fever, typhoid fever and yellow fever. This system caters to the needs of those who lack Internet access or who are computer-illiterate, low-literate, or visually impaired. A cross-sectional study was conducted using a questionnaire that gathered demographic data about the study participants and their satisfaction and readiness to accept the system. The user satisfaction results showed a mean of 3.98 (approximately 4), which is the recommended average for a good usability study. Dialogue systems of this kind help to provide cost-effective and equitable access to health information that can protect the population from tropical disease outbreaks. They serve the low-literate, the computer-illiterate, and the visually impaired.

7.1 Introduction

The Internet serves as a repository for different kinds of information. There is rarely a subject on which information cannot be gleaned on the Internet, including health. There were 2.1 billion Internet users world-wide in 2011 (Hadlaczky et al. 2013). Jesaimini et al. (2013) state: “One of the most cited reasons for accessing the Internet is searching for health information.” Patients access medical information through taking part in online discussion groups, searching for health information in medical databases, arranging for consultations with doctors, and using self-administered treatment and diagnosing tools found on line (Bessel et al. 2002). Patients also seek, in addition to health information, emotional support through websites that are devoted to a particular disease as well as from online support groups and electronic mailing lists that give newsy updates to patients who have signed up for these regular email alerts (Alejandro & Gagliardi 1998).

Access to useful health information (HI) and medical information (MI) on the Internet can be lifesaving in underdeveloped countries. For example, in Nigeria the current life expectancy is 49 years according to the 2010 report of the World Health Organization (WHO). That report lists malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia, prematurity, birth asphyxia, neonatal sepsis, HIV/AIDS, congenital abnormalities and injuries as the most common causes of death, in rank order. Some of the major illnesses that lead to mortality in Nigeria, such as those listed above, could have been prevented with simple medications and healthy lifestyles (Acho 2005). Most certainly, the situation could have been different if the populace were aware of the availability of health information on the Internet and were able to make proper use of such information. This is especially so because the Internet has a lot of prospects in supporting health care and self-care (Bernhardt 2000; Baker et al. 2003; Lintonen et al. 2008; Weaver et al. 2009). Health-related information on the Internet could help patients to be better informed, obtain more knowledge about their illnesses and conditions, and consequently be more involved in the decision making process concerning their health, rather than passively sitting by as the peril of illness and disease consume their vitality. No doubt, such access to online health information could improve patients’ health by ensuring that they have more appropriate healthcare services that are sorely needed at the early stages of illness (Diaz et al. 2002; Lupiáñez-Villanueva 2011).

7.2 Related work

Jesaimini et al. (2013) reviewed literature up to March 2012 in an effort to investigate which kinds of users searched for health information on the Internet and for what purposes. Their specific focus was on medication information in particular. Their study covered patients in the general population rather than in one specific region. They studied patients’ use of the Internet in North America and Europe, in the Middle East and Asia, and in Australia and New Zealand. Their results showed that nearly one half of the general population and 50%–99% of adults suffering from a chronic disease had used the Internet to search for health information, primarily about a specific disease, its treatment, exercise, and diet. As regards medications, approximately one half of the online health information seekers, whether patients or not, looked for medical information concerning side effects, drug safety, interactions, update on drugs currently consumed, new drugs, and over-the-counter or alternate medications. Women, adults older than 50 years, and well-educated people searched considerably more frequently for health information and medical information. The reasons to search on line for medical information were convenience, broad range of information, and peers’ opinions. The online searches for medical information did not replace health professionals’ information, but offered additional information and a possibility to crosscheck. Interestingly enough, the study results also showed that not only can online medical information reassure a patient or incentivize them to ask questions from the treating physician, but online health-related information can likewise confuse the patient. This is so because the patients’ lack of medical expertise creates confusion when presented with large amounts of, sometimes contradictory, information which can be hard to sift through and digest.

Oyelami et al. (2013) investigated Nigerians’ Internet pattern usage. This included studying patients’ awareness of the availability of health-related information on line, as well as an examination of the key factors that influenced their use of the Internet for self-care health information. A questionnaire-based assessment of 205 individuals selected randomly was carried out. The results indicated that 61% of the participants used the Internet for self-care (self-diagnosis and treatment in lieu of seeking help from the medical profession) and were aware of the availability of health information on the Internet, which they readily pursued to find answers to their health concerns. The participants in this study also reported that they had used the Internet for purposes other than seeking health-related information. Those purposes included communication, social networking, general research, and banking. The results validated study participants’ perceived ease of use, compatibility (consistency with the values or norms of potential adopters of a technology and the similarity with existing standards), Internet self-efficacy (belief in a person’s ability to succeed in a specific situation), and technical support and training, as factors to consider in using the Internet for self-care.

Jo et al. (2010) carried out a survey to reveal the patterns of utilization of health information on the Internet among native residents of the metropolitan city of Incheon and simultaneously in the Gangwon province of South Korea. Their results revealed the following categorical breakdown for the health information that people sought on the Internet: general health tips (64.2%); disease specific information (32.0%); shopping for health commodities such as HIV test kits, contraceptive devices, etc. (23.7%); and selection of hospitals (19.3%). The survey showed that people with a higher education and higher income level were inclined to use the Internet more often for health information than those who were less educated and had less income. Similarly, metropolitan city residents used health information found on the Internet more often than those leading a more humble lifestyle living in the outer lying province. One’s personal health status appeared to be the most important factor in determining the use of the Internet for searching information about general health tips. For example, healthy people (68.3%) used the Internet more than those plagued by illnesses (44.4%). However, among the population of ill people who availed themselves of the Internet, they were found to use the Internet most frequently for disease-specific information (62.6%). Residence area (where a person resides) was the most important factor of online shopping for health commodities. For instance, whereas 31.8% of city dwellers used the Internet for purchasing health commodities, only 19% of those living in the province used it for the same purpose. Similarly, residence area, age, and health examination were the determinant factors for the utilization of the Internet for hospital selection.

AlGhamdi & Moussa (2012) through a self-administered questionnaire (a questionnaire that is administered without an interviewer) carried out a study to determine how the public uses the Internet in Saudi Arabia to search for health-related information. As part of the study, the respondents were ask to evaluate their perceptions of the quality of information they found on the Internet when compared with the information they obtained from their own healthcare providers. Their results showed that 87.8% of the study respondents used the Internet generally and 58.4% used the Internet for searching specifically for health-related information. While 89.3% reported that a doctor was their primary source of health information, 84.2% of those surveyed agreed that searching for health information on the Internet was useful. The reasons given were: (1) curiosity (92.7%); (2) not getting sufficient information from their doctors (58.5%); and 3) not trusting the information given to them by their doctors (28.2%). In fact, 44% of study participants searched for health information before going to the clinic; 72.5% of the study respondents discussed the information they obtained from the Internet with their doctors. And nearly all those who did so (71.7%) believed that this positively affected their relationship with their doctor. Health information search was more frequent among the 30–39 year age group as well as those with university or higher education, employed individuals, and high-income groups.

The work by Sadasivam et al. (2013) reveal that not only do individuals who need health information search for it, but there is similarly a category of health information seekers called “surrogate seekers” – those who actively search the Internet for relevant health infomation for persons other than themselves. Members of this category search for health-related information for their family members or friends who may be suffering from serious health conditions. It is important to address this category because they are frequent visitors of the Internet along with those who search the web for information related to their own conditions. The study seeks to identify the unique characteristics of surrogate seekers, showing how they differ from self-seekers of health information. The researchers contend that by “identifying the unique characteristics of surrogate seekers [this] would help in developing Internet interventions that better support these information seekers.”

From all the related work described above, it can be seen that the vital health information accessed by the patient, or their advocate, appears in text format only. However, if a consumer is not computer literate, has no access to the Internet, is visually impaired, or is suffering from literacy problems in general, such a consumer is clearly at a disadvantage. Hence, it is imperative that we attend to the needs of these special categories of individuals who would benefit from the massive amount of health-related information found on line.

7.3 Dialogue systems

According to Bickmore & Giorgino (2006), a dialogue is discourse between two or more parties, including a human and a computer. Bickmore and Giorgino (2006) and Alan et al. (2004) defined a dialogue system as a computer system that communicates with a human.

Even though there are proprietary solutions for developing dialogue systems, VoiceXML is the W3C standard designed for human-computer audio dialogues that feature synthesized speech, digitized audio, recognition of spoken, DTMF (Dual Tone Multi Frequency) key input, recording of spoken input, telephony and mixed initiative conversations (José 2007; W3C 2001). The main goal of VoiceXML is to bring the full power of Web development and content delivery to voice response applications and to free the authors of such applications from low-level programming and resource management. VoiceXML enables integration of voice services with both data services, using the familiar client-server paradigm (W3C 2001). For a traditional webpage, a Web browser will make a request to a Web server, which will, in turn, send an HTML document to the browser to be displayed visually to the user. However, for a dialogue system, it is the VoiceXML Interpreter that sends the request to the Web server, which will return a VoiceXML document to be presented as a dialogue system via a telephone.

Dialogue systems for calling up web-based medical content play a special role in underdeveloped countries. Nigeria presents an interesting test case in that the low level of computer literacy serves as one of the major impediments to accessing health information on the Internet (Jegede & Owolabi 2003; Esharenana & Emperor 2010). Furthermore, only 27.3% of the world population has access to computers, and 25.9% have access to the Internet (ITU 2009). Consequently, one technology that can be used to overcome the accessibility problem is telephonic communication. In fact, telephones outnumber computers on the planet (José 2007), and 67% of the world population has access to them as stated in the ITU report (2009). Given the ubiquity of telephones, HI and MI may be made accessible to the Nigerian populations of the computer-illiterate, low-literate and the visually impaired via the proper use of the spoken dialogue system, which we describe below. This system is accessible via both fixed lines (landlines) and mobile phones. Dialogue systems provide interactive voice dialogues between a human and a computer. They have the potential of being used to provide ubiquitous, cost-effective and wide-scale services to a vast majority of people (David 2006). They can also be used to provide access to health information available on the Internet to the visually-impaired. In this work, below, we explore how Health Dialogue System (HDS) provides access to health information. We show how the system was developed and evaluate its performance for acceptability and user-satisfaction.

7.4 Methods

The Health Dialogue System (HDS) was developed using VoiceObjects Desktop for Eclipse 11. This is an Eclipse-based IDE for designing, developing, testing, deploying and administering of voice, video, text and Web-based applications. Voxeo Prophecy 13 was used as the implementation platform consisting of a speech server and VoiceXML engine. Voxeo Prophecy is a standards-based premise voice platform that is used by Voxeo customers worldwide for inbound IVR, outbound notification, innovative VoIP applications, and more. All these tools allow for testing of voice applications without having to deploy them on the telecommunication service providers’ networks. A white female voice was used by HDS in interacting with the participants. By default, Voxeo Prophecy’s text-to-speech (TTS) system can be used in either a white female voice or a white male voice mode. HDS was tested using an in-built soft phone in Voxeo Prophecy.

7.4.1 Participants

The evaluation of HDS was carried out among 19 undergraduates of Landmark University, which is located in Omu-Aran, Kwara State, Nigeria. Of all of the 19 subjects that participated in the study, one subject did not complete the questionnaire. Each of the subjects that participated in the evaluation was informed beforehand of what services HDS offers and how to interact with the system. Each was subsequently invited to test the system on a laptop computer running Windows 8. After the test, each subject was given a questionnaire to fill out.

7.4.2 Demographics of the participants

Nine of the participants were male while five were females. The remaining four subjects chose not to specify their sex. Ten of the participants were less or equal to 20 years of age, five were within the 21–30 age range, while three did not specify their age range.

7.4.3 Data collection

In measuring user satisfaction of the system, items in questionnaires used in similar studies by Kwan & Jennifer (2005) and Walker et al. (1999) were adopted. The measures used in the questionnaires have both face and content validities. For face validity, all measures were constructed by experts with over 10 years of experience in usability tests of mobile and speech user interface (SUI) applications. In terms of content validity, the measures covered all dimensions of usability in telephony applications as defined by the European Telecommunications Standard Institute (ETSI) (Kwan & Jennifer 2005). However, a modification was made to the questionnaire by Kwan & Jennifer (2005) by the changing of some adjectives to their simpler synonyms in a bid to aid the participants’ understanding. The questionnaire used was scaled 1–5.

7.5 Health dialogue system (HDS)

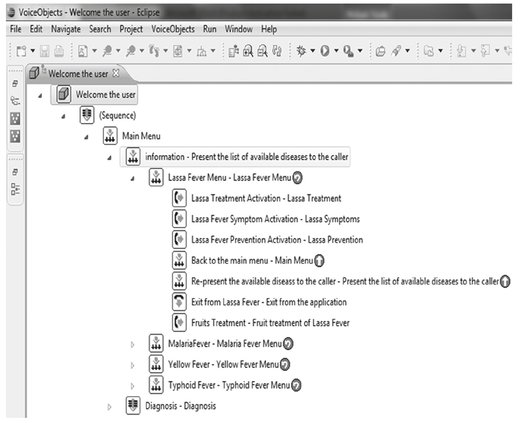

The prototype system developed provides health information about fevers rampant in Nigeria. The system when called up by the user proceeds to welcome the user and then quickly informs the user of the services it renders. The user is then expected to make a choice from a list of diseases – lassa fever, malaria fever, yellow fever and typhoid fever – in order to get information about those diseases. Once a selection is made, the system presents general information about the specific fever. The caller is then asked to select information about any of the following aspects of the fever: symptoms of the fever; how to treat it; information about fruits that can be used in treating the fever; and how to prevent it. The caller also has the option of listening to the list of the diseases again before exiting from the application. The dialogue flow generated by VoiceObjects is shown above in Fig. 7.1.

Fig. 7.1: Dialogue flow of HDS.

Figure 7.2 below shows HDS being tested with the Prophecy 13 in-built soft phone.

Fig. 7.2: Calling HDS with Prophecy 13 in-built soft phone.

7.6 Results

7.6.1 Experiences with mobile/computing devices

As shown in Tab. 7.1 below, five (27.8%) of the study participants rated their experiences/skill in the use of computer as “expert.” Ten (55.6%) rated their skills as “good.” Two (11%) rated their skills as “average” while one (5.6%) rated his computer skills as “novice.” Eight of the participants (44.4%) primarily used a desktop PC to do their work, while 10 (55.6%) made their laptop their primary computing device. Fifteen of the participants (83.3%) owned a mobile phone or personal digital assistant (PDA); two (11.1%) did not own either a mobile phone or a PDA. Lastly, one participant (5.6%) did not specify this option about a mobile device all together. Of all those that owned a mobile device, 14 (77.8%) had owned a mobile phone/PDA for more than 2 years while only one (5.6%) participant had owned such a device for 2 years or less. Three of the participants (16.6%) did not specify the duration of their ownership of a mobile device. When questioned about frequency of usage, as seen in Tab. 7.1, the results show that 14 (77.8%) of the respondents made or received calls more than seven times a week; one respondent (5.6%) made calls 5–6 times in a week; one respondent (5.6%) made calls once a week; and two of the respondents (11%) did not make any calls at all.

Tab. 7.1: Experiences with mobile/computing devices.

| Item | Category | % |

|---|---|---|

| Software usage skill | Novice | 5.6 |

| Average | 11 | |

| Good | 55.6 | |

| Expert | 27.8 | |

| Device used for work | Laptop | 55.6 |

| Desktop PC | 44.4 | |

| Ownership of phone/PDA | Mobile phone/PDA | 83.3 |

| No ownership | 11.1 | |

| No response | 5.6 | |

| Duration of ownership of phone/PDA | > 2 years | 77.8 |

| <2 years | 5.6 | |

| No response | 16.6 | |

| Frequency of making or receiving of calls weekly | > 7 times | 77.8 |

| 5–6 times | 5.6 | |

| 1 time | 5.6 | |

| No response | 11 |

7.6.2 User satisfaction and acceptability of HDS

In response to the question, “Would you like to access health information using this kind of system? If yes, why?” Seventeen of the respondents (94%) responded “yes” while one (6%) did not specify this option. These results showed a user satisfaction mean average of 3.98. Such results imply that all the participants approved access to health information via dialogue systems in that a satisfaction result of 3.98, which is approximately 4, comports with the recommended average for good usability studies on 1–5 scale (Sauro & Kindlund 2005).

Table 7.2 below lists all the reasons given by the study participants for their satisfaction and acceptance of HDS.

Tab. 7.2: Satisfaction of use and acceptability of HDS.

| “It can be used in times of emergencies” |

| “Because I believe it can be useful” |

| “The application is really interesting” |

| “Because I found the application easy to understand” |

| “Because I figured it would just make things a whole lot easier” |

| “I believe it would be of much help” |

| “It was easy to understand and operate” |

| “The system is easy to understand and communication is clear” |

| “Is quite easy and understandable” |

| “Because it is more easy and able to understand by a novice” |

| “It is easy to use” |

| “It is easy to use and gives some symptoms about health information” |

| “Because it was a bit easy to navigate around it” |

| “It provided a first aid guidance to minor health issues” |

| “It provides health information with speed and ease”. |

7.7 Conclusion

From the results presented above, it can be demonstrated that the users were both satisfied with the dialogue system and that they were readily inclined to access health information using this kind of telephony system. From their responses to the question on why they would like to access health information using dialogue systems, it is obvious that simplicity of use; understandability of the system [even though a white female voice was used in communicating with the participants]; usefulness of such systems; ease of use and navigation of the system; usefulness in providing first aid; and usefulness in making life easier were factors that contributed to the success of the dialogue system. Therefore, any system intended to provide health information should take into consideration these useful and practical features. This kind of system can be used to provide both cost-effective and readily available access to health information, which has heretofore been available on the Internet in text form only. This way, the Internet can better serve the populations of low literate, computer illiterate and the visually impaired, who without this Health Dialogue System would not have been able to access online information about debilitating and, in some instances, life threatening infectious diseases commonly found in Nigeria. Such systems provide a more equitable access to web-based health information for those who cannot readily access this information on line.

Acknowledgment

The author appreciates the efforts of Ogundaini Michael of the Department of Physical Sciences, Computer Science program of Landmark University, Omu-Aran, Kwara State, Nigeria in helping to administer the tests and the questionnaire.

References

Acho, O. (2005) ‘Poor healthcare system: Nigeria’s moral difference’, Available at: http://www.kwenu.com/publications/orabuchi/poor_healthcare.htm [Accessed 28 April 2008].

Alan, G. B. (2004) Elementary Statistics: A Step by Step Approach. New York: McGrawHill, pp. 340–342.

Alejandro, R. J. & Gagliardi A. (1998) ‘Rating health information on the internet navigating to knowledge or to babel?’, JAMA, 279:611–614.

AlGhamdi, K. M. & Moussa, N. A. (2012) ‘Internet use by the public to search for health-related information’, Int J Med Inform, 81:363–373.

Baker, L., Wagner, T. H., Singer, S. & Bundorf, M. K. (2003) ‘Use of the Internet and e-mail for health care information: results from a national survey’, JAMA, 289(18):2400–2406.

Bernhardt, J. M. (2000) ‘Health education and the digital divide: building bridges and filling chasms’, Health Educ Res, 15(5):527–531.

Bessell, T. L., McDonald, S., Silagy, C. A., Anderson, J. N., Hiller, J. E. & Sansom, L. N. (2002) ‘Do Internet interventions for consumers cause more harm than good? A systematic review’, Health Expect, 5(1):28–37.

Bickmore, T. & Giorgino, T. (2006) ‘Health dialog systems for patients and consumers’, J Biomed Inform, 39(50):556–572.

David, E. T. (2006) ‘Press 1 to promote health behaviour with interactive voice response’, Am J Manag Care, 12(6):305.

Diaz, J. A., Griffith, R. A., Ng, J. J., Reinert, S. E., Friedmann, P. D. & Moulton, A. W. (2002) ‘Patients’ use of the Internet for medical information’, J Gen Intern Med, 17:180–185.

Esharenana, E. A. & Emperor, K. (2010) ‘Application of ICTs in Nigerian secondary schools’, Library Philosophy Practice (e-journal), 1–8.

Hadlaczky, G., Carli, V., Sarchiapone, M., Värnik, A., Balázs, J., Germanavicius, A., Hamilton, R., Wasserman, D. & Masip, C. (2013) ‘Suicide prevention through internet based mental health promotion: the supreme project’, European Psychiatry, 28(1).

ITU (2009) The World in 2009: ICT Facts and Figures. Available at: http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/material/Telecom09_flyer.pdf. [Accessed 20 March 2011].

Jegede, P. O. & Owolabi, J. A. (2003) ‘Computer Education in Nigerian Secondary Schools: Gaps Between Policy and Practice’, Meridian, 6(2):1–5. Available at: http://www.ncsu.edu/meridian/sum2003/nigeria/index.html [Accessed 29 January 2014]

Jesaimini, A., Rollason, V., Cedrashi, C., Luthy, C., Besson, M., Boyer, C., Desmeules, J. A. & Piguet, V. (2013) ‘Searching for Health and Medication Information on the Internet. A review of the literature’, Clin Ther, 35(8S):e17.

Jo, H. S., Hwang, M. S. & Lee, H. (2010) ‘Market segmentation of health information use on the Internet in Korea’, Int J Med Inform, 79:707–715.

José, R. (2007) ‘Web services and speech-based applications around VoiceXML’, J Netw, 2(1):27–35.

Kwan, M. L. & Jennifer, L. (2005) ‘Speech versus touch: a comparative study of the use of speech and DTMF keypad for navigation’, Int J Hum-Comp Int, 19(3):343–360.

Lintonen, T. P., Konu, A. I. & Seedhouse, D. (2008) ‘Information technology in health promotion’, Health Educ Res, 23(3):560–566.

Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F. (2011) ‘Health and the Internet: Beyond the Quality of Information’, Rev Esp Cardiol, 64(10):849–850.

Oyelami, O., Okuboyejo, S. & Ebiye, V. (2013) ‘Awareness and usage of Internet-based health information for self-care in lagos state, Nigeria: implications for healthcare improvement’, J Health Inform Develop Count, 7(2):165–177.

Sadasivam, R. S., Kinney, R. L., Lemon, S. C., Shimada, S. L., Allison, J. J. & Houston, T. K. (2013) ‘Internet health information seeking is a team sport: Analysis of the Pew Internet Survey’, Int J Med Inform, 82:193–200.

Sauro, J. & Kindlund, E. A. (2005) ‘Method to Standardize Usability Metrics into a Single Score’, ACM, CHI. Portland, Oregon, USA, 2–7 April.

Walker, M., Litman, D. & Kamm, C. (1999) ‘Evaluating spoken language systems’, Am Voice Input/Output Society (AVIOS), 25.

Weaver III, J. B., Mays, D., Lindner, G., Eroǧlu, D., Fridinger, F. & Bernhardt, J. M. (2009) ‘Profiling characteristics of Internet medical information users’, J Am Med Inform Assoc, 16(5):714–722.

W3C. (2001) Voice Extensible Markup Language (VoiceXML) Version 2.0. Available at: http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-voicexml20-20040316/. [Accessed 29 October 2013].

World Health Organization. (2010) World Health Statistics 2010. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS10_Full.pdf [Downloaded: 23 September, 2013].