Introduction

Much has changed since I wrote the first edition of The Art, Science, and Craft of Great Landscape Photography in 2014. My knowledge has deepened, technology has advanced, and the techniques I use to plan, scout, shoot, and process images have evolved. The time has come for a second edition. Here’s a snapshot of what’s new.

Smartphone apps for planning photo shoots have improved dramatically. The best apps now have position-search capabilities that make it simple to answer questions like:

“What are the best days this year to shoot the full moon setting over Longs Peak as seen from the summit of Twin Sisters?”

“When will the sun rise through Turret Arch and South Window simultaneously?”

“What time of year, and what time of night, is ideal for shooting a Milky Way panorama at Goblin Valley State Park?”

Editing software has also improved. For example, high-dynamic-range imaging techniques, which I once used only as a last resort, have now become my go-to solution for high-contrast scenes where nothing is moving in the frame. My approach to editing night images has evolved. For example, rather than shifting the entire image toward blue to create a blue sky, I now seek to preserve the colors my eyes can see at night, such as the colors of bright stars and planets, while shifting only the color of the background sky to the deep blue we imagine the sky should be.

My understanding of atmospheric optics, the science of how sunlight interacts with our atmosphere, has deepened, particularly when it comes to twilight glows and how they can be enhanced by recent volcanic eruptions. I’ll explain how my new knowledge has led me to shoot beautiful landscape images I might previously have missed, and how you can do the same.

I’ve expanded my discussion of composition to provide greater insights into the art of landscape photography. And I’ve replaced almost all of the images in the first edition with fresh images illustrating the major points. All images are now accompanied by camera, lens, and exposure data, as well as other technical details about the image.

The first edition of the book was aimed primarily at photographers who already knew the basics. In this edition I’ve added a chapter on photographic fundamentals to help less-experienced photographers come up to speed. This chapter explains the exposure triangle (aperture, shutter speed, and ISO), and white balance. I’ve also included a discussion of auto-focus modes, auto-exposure bracketing, depth of field, and hyperfocal distance.

Sunset at Delicate Arch, Arches National Park, Utah. Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L III USM at 35mm, three-frame bracket set, two-stop bracket interval at ISO 100, images merged using Lightroom Classic’s Photo Merge>HDR utility.

In addition to all the substantive changes, the second edition features a less-obvious improvement. I began teaching landscape photography workshops in 2002. There’s nothing like explaining a complex subject to a live audience to reveal the places where students struggle to understand—and to teach me the best ways to explain difficult concepts. The first edition benefited greatly from that experience. During the five years since publication of the first edition, I have taught several dozen group workshops and many private, one-on-one workshops. That additional experience has further refined my approach to explaining the art, science, and craft of landscape photography.

Some things haven’t changed. Recently a student at a workshop I was teaching at Great Sand Dunes National Park asked a question. We had just finished shooting the Milky Way soaring over a wind-sculpted sand dune on a crystal-clear night. She asked, “Have you ever lost your sense of wonder at the beauty of the natural world?” I replied, “Never. If I ever lose my sense of wonder, I will stop shooting.”

I still think of landscape photography as the pursuit of visual “peak experiences.” I’m borrowing a term here from humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow, who studied human potential—the heights to which humans can aspire, not the depths to which they can sink. According to Maslow, peak experiences can give “a sense of the sacred, glimpsed in and through the particular instance of the momentary, the secular, the worldly.” Whoa! That sounds awfully pretentious. But when I think back on the most beautiful scenes I’ve ever witnessed, I understand what Maslow was talking about. Visual peak experiences are moments of extraordinary natural beauty, often ephemeral, that I try to capture in such a way that a viewer of the photograph can share my sense of wonder and joy. Granted, my photographs rarely, if ever, achieve such lofty heights. Perhaps they never truly will. But for me it is the pursuit of visual peak experiences, and the arduous, ecstatic struggle to capture them on my camera’s sensor, that makes landscape photography endlessly fascinating.

The Milky Way over towers near the Joint Trail, Needles District, Canyonlands National Park, Utah. Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, Canon EF 35mm f/1.4L II USM. Land: one row, three camera positions, four frames per camera position, images stacked in Photoshop, noise reduced with Stack Mode>Median, 2 minutes, f/1.4, ISO 6400. Sky: two rows, three camera positions per row, four frames per camera position, images aligned and noise reduced in RegiStar, 10 seconds, f/1.4, ISO 6400.

For me, these marvelous moments occur most often in wild places, particularly in the mountains. Even after 50 years, I still remember a peak experience that occurred during a camping trip with my parents in the desert mountains of southern California. I was 12 and hungry for child-size adventure. Alone, I walked away from our campsite to a saddle in a ridge overlooking a vast desert valley and the mountain ranges beyond. It was a journey that an adult would have measured in mundane yards and minutes; I measured it in emotional light-years. For a timeless interlude I meditated on the ridge, soaking in the silence and the unfathomable sweep of land. I remember feeling utterly isolated in a desolate world, and yet I recall no desire to flee back down the path to camp. Something about the sheer unrepentant emptiness of the land compelled my awestruck attention and has demanded my return to the mountains again and again.

F.W. Bourdillon, a British mountaineer who tried to climb Everest a century ago, captured my feelings when he explained the secret motivation of mountain-lovers as “a feeling so deep and so pure and so personal as to be almost sacred—too intimate for ordinary mention.” Mountains, he went on to say, “. . . move us in some way which nothing else does . . . and we feel that a world that can give such rapture must be a good world, a life capable of such feeling must be worth the living.”

In my early teen years I hiked the valleys and scrambled up the easy peaks in California’s Sierra Nevada. Then, at 15, I took up technical rock-climbing. When I moved to Boulder, Colorado, to go to college in 1975, I added ice-climbing to my quiver of mountain skills and began tackling difficult routes on peaks from Alaska to Argentina. In my mid-30s, after 20 years of intense mountaineering, my interest in climbing high peaks began to wane, while my interest in photographing them blossomed. Landscape photography, I found, could be just as much of an adventure as mountaineering. True, the challenges were different, but the pulse-pounding excitement and the need to perform gracefully under pressure were still there. At one time I had struggled out of bed at 1:00 a.m. to climb a long, demanding route on a high peak before the afternoon thunderstorms struck; now I rose at the same absurd hour to race the rising sun to a photogenic vantage point. My motto for sunrise shoots is simple: sleep is for photographers who don’t drink enough coffee. All these early starts have led me to formulate the first dictum in Randall’s Rules of Landscape Photography: Never eat breakfast before midnight. If you must get up before midnight to do a photo shoot, eat dessert.

Pikes Peak rises above the fog blanketing South Park at sunrise as seen from the summit of 14,286-foot Mt. Lincoln, Mosquito Range, Colorado. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF 70-200mm f/4L IS USM at 200mm, 1/100th, f/8, ISO 100.

I quickly learned one of the fundamental paradoxes of landscape photography: The potential reward is always greatest when the odds against you are the longest. The most likely outcome on a day with heavy clouds is that the sun will rise or set into gray murk. Creating evocative landscape images will be almost impossible. But if that rising or setting sun finds a tiny gap between dense clouds and the horizon, the result can be some of the most spectacular light you’ve ever seen. When that happens, you may have only seconds to compose the shot and capture the image. In many cases, such an opportunity will not occur again for weeks or even months.

Hallett Peak from the Flattop Trail during a windstorm at sunrise, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado. Zone VI 4×5 field camera, Fujichrome film. Lens and exposure unrecorded.

I also learned that the most powerful moments in the natural world are transitory. One vicious hailstorm can flatten all the wildflowers in an entire valley. Miss a shot of fall foliage, and you may have to wait an entire year for another chance. The fall color display is always fleeting; the leaves reach their peak of color just as the stems become so brittle that the slightest breeze sends them spinning to the ground. The most magical winter wonderland can enchant photographers only briefly; all too soon, the sun and wind strip the snow from the trees, and the world becomes ordinary once more. Recently I relocated two marvelous weathered trees near the summit of Twin Sisters that I last photographed 20 years before. One had fallen and lost the golden patina that made it so appealing two decades earlier; small trees had sprung up around the other tree, obscuring the view of Longs Peak that had once made the shot so compelling. Time never repeats itself, of course, but the sustained pursuit of landscape photography hammers home that truth with a poignancy we rarely feel in our busy, ordinary lives. As Pablo Picasso put it, “The purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our souls.” I believe that applies to the creation of art as much as to its enjoyment.

When I first became a full-time landscape photographer, in 1993, the only way to share these marvelous moments was to capture them on film. In the film era, most people assumed that an image was a truthful representation of the world unless proven otherwise. Today, in the digital era, peoples’ perception of photographs has changed: Many people assume a digital image has been enhanced unless proven otherwise. Given my reverence and respect for wild land, it probably goes without saying that I believe authenticity still matters in landscape photography. I practice what you might call “nature photojournalism.” Most images that have enduring power are also authentic. To take an example from the world of current-events photojournalism, recall the famous photograph of the lone protester standing in front of a phalanx of tanks in Tiananmen Square during pro-democracy demonstrations in China in 1989. That image is so powerful that the Chinese government has banned Internet searches for it in China. If that image had been a still taken on a Hollywood movie set, with some Hollywood actor as Tank Man and all the tanks created using CGI, would that image have anything like the power it does? I think not.

Clearing storm over columbine and Lone Eagle Peak, Indian Peaks Wilderness, Colorado. Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, Canon TS-E 24mm f/3.5L II tilt-shift lens, 1/15th, f/16, ISO 100.

Some people argue that images can never truly capture the real world, so any claim to authenticity is absurd. I readily acknowledge that there are significant differences between viewing the real world and viewing a photograph of it. Indeed, understanding and overcoming those differences are a major topic in this book. However, I believe it’s possible to draw a line between an image that reflects reality in some fundamental way and one that doesn’t. I want to be able to tell someone viewing my work, “What you see in my prints is what I saw through the lens.” I want the viewers of my work to exclaim, “Wow! What a magnificent world we live in!” not to think, “Wow! That guy really knows Photoshop.”

From Peak Experience to Well-Crafted Image

To be a good landscape photographer today, you need the brain of an engineer and the heart of a hopeless romantic. Creating an evocative landscape photograph requires both an emotional connection to the scene and an understanding of the science and craft of creating compelling images. My approach to teaching landscape photography can be summed up in ten words: Master the science and craft, and the art will follow.

Mt. Herard and Medano Creek at sunset, Great Sand Dunes National Park, Colorado. Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L III USM at 30mm, 0.6 seconds, f/16, ISO 100.

The craft of landscape photography obviously includes photography itself: aperture, shutter speed, ISO, white balance, depth of field, and so on, all of which I cover in chapter 1. But the science and craft of landscape photography goes far beyond such photographic basics.

Understanding key scientific concepts from fields as diverse as geography, optics, vision, and psychology can help landscape photographers create captivating images.

A knowledge of geography helps photographers understand how the direction of the sun at sunrise and sunset varies tremendously between summer solstice and winter solstice. At the latitude of Denver, the difference is 60 degrees. In Fairbanks, Alaska, the difference is 140 degrees.

A knowledge of atmospheric optics, the science of how sunlight interacts with our atmosphere, explains why the sky is often blue, sunsets are sometimes red, and why tall mountains rising abruptly above the plains can receive beautiful light. Understanding atmospheric optics also permits the knowledgeable photographer to predict where rainbows will appear and why polarizers sometimes enhance reflections and sometimes remove them. Atmospheric optics also explains the origin of gap light and glow light, some of the rarest light you’ll ever be privileged to photograph, and how volcanic eruptions thousands of miles away affect the character of the light you see.

The science of landscape photography also includes an understanding of how the complexities of human vision affect the way we see the world and the way we view art. For example, the brightest highlight in which our eyes can see detail is about 10,000 times brighter than the darkest shadow in which we can see detail. The brightest highlight in a photographic print is only about 50 times brighter than the darkest shadow. One of the fundamental problems for a landscape photographer is finding the best way to compress the very broad range of tones we see in the real world into the much narrower range of tones we can reproduce in a print. This book tackles this problem from many angles, starting with calculating exposure in the field and concluding with a variety of techniques in the digital darkroom. These techniques include the Rembrandt Solution, my name for a technique used by the 17th-century master painter that is still relevant in the digital age. Used properly, the Rembrandt Solution can create the illusion of greater dynamic range in a print than what actually exists.

Twilight glow on Delicate Arch and the La Sal Mountains about 18 minutes after sunset, Arches National Park, Utah. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L II USM at 35mm, 8 seconds, f/16, ISO 100.

The craft of landscape photography includes the ability to plan shoots and locate promising subjects using topographic maps and computerized mapping tools. These computer programs help photographers visualize how light will play across the landscape and enable them to answer questions such as, “What is the best day to photograph the full moon rising through Utah’s world-famous Delicate Arch at sunset?” It includes scouting, the task of getting to know an area in depth. And it includes mastering the four basic exposure strategies for landscape photography, so that you are equipped to handle any lighting situation that nature throws at you.

South Window through Turret Arch at sunrise, Windows area, Arches National Park, Utah. The rising sun is visible through both arches simultaneously on only eight days per year. Zone VI 4×5 field camera, Fuji Pro 160S color negative film. Lens and exposure unrecorded.

That, in a nutshell, is the science and craft of landscape photography. So how can mastering these topics lead to creating art? Can an authentic landscape photograph also be creative? I think it can be if you understand what I mean by creative. I think there are two major misconceptions about creativity that hold photographers back. The first is that only geniuses can be creative, to which I say, balderdash. The second is that creativity occurs when you sit in a darkened room until amazing ideas pop into your head. That’s not how creativity works, at least not in the context of landscape photography. I think creative landscape images occur when photographers make a new, unexpected, but suddenly obvious connection between seemingly unrelated information already stored in their head. Here’s an example.

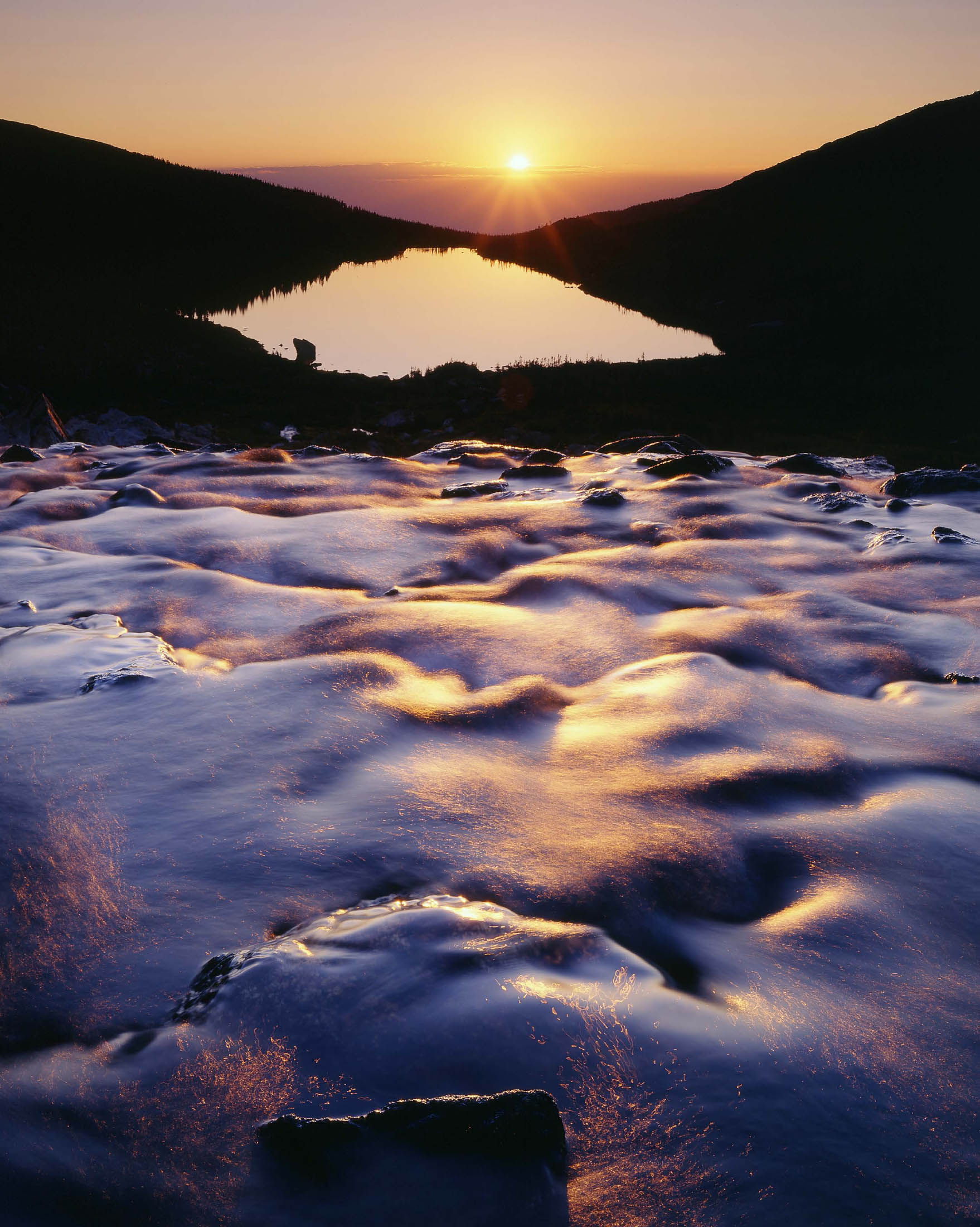

I was hiking with my wife Cora in Colorado’s Indian Peaks Wilderness in the middle of the day in July when I came across a stream that fed into Lake Isabelle. The stream looked quite ordinary in the noon light. I noticed, however, that I could see the plains to the east through a notch in the foothills at the east end of the lake. I knew from my understanding of atmospheric optics that any time you’re in the mountains and can see the plains either to the east or west, you’ve got potential for exceptionally red light on your foreground. In this case, I envisioned warm sunrise light illuminating the stream as it flowed toward the rising sun. I shot a compass bearing to the notch and wrote the bearing down in the notebook I always carry. When I got home, I used an app to look up when the sun would rise at the same bearing as the notch and learned it would occur both in late August and mid-April. In mid-April the stream would still be snow-covered and frozen, but late August seemed promising. I returned twice that year and once again a year later before making my favorite image of this location, which I call Sunrise above Lake Isabelle. By combining my knowledge of atmospheric optics, geography, planning apps, and how to manage high-contrast scenes, I had come up with an image that in no way resembled the ordinary stream I saw in midday light. (Chapter 4 describes the apps I use today in similar situations.)

Making images that capture your visual peak experiences and evoke emotion when you view them later is a satisfying achievement. To be truly successful as an artist, however, your images must speak to a wider audience. An understanding of the psychology of how we view art can strengthen your work. I’ll discuss the distinction between images that are merely different and those that are genuinely creative. I’ll also describe the critical importance of relevance, as demonstrated by research conducted with my images by advertising researcher Bruce Hall. As Robert Solso, author of Cognition and The Visual Arts put it, “An artist does not create art any more than a physicist creates physics.” What he meant is that physicists don’t invent the laws of physics; they try to uncover the laws that describe the seemingly chaotic phenomena they observe. Similarly, successful images aren’t generated randomly; they must fit like a key into the lock of the viewer’s emotions—triggering memories, evoking anticipation, and helping viewers imagine the feelings they would have experienced if they had been standing next to the photographer when the image was captured.

The shallow stream above Lake Isabelle where I shot Sunrise above Lake Isabelle, Indian Peaks Wilderness, Colorado. Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L III USM at 35mm, 1/30th, f/11, ISO 100.

Sunrise above Lake Isabelle, Indian Peaks Wilderness, near Boulder, Colorado. Zone VI 4×5 field camera, Fujichrome film. Lens and exposure unrecorded.

Before you can set out on your own personal vision quest, you need a working knowledge of your camera gear. In this book, I’ll assume you’re already familiar with the basic operation of your camera, such as how to set the aperture, shutter speed, and ISO to get what your in-camera meter considers to be the right exposure. (I’ll explain why you should choose various settings for these parameters in chapter 1.) You should be familiar with the various exposure modes your camera probably offers, such as program, aperture-priority, shutter-priority, and manual. You should know how to use exposure compensation to vary the exposure the sensor receives, and you should know how to set the white balance and choose the meter mode. I’ll assume you know how to download images from your memory card and make basic adjustments to color and density with image-editing programs.

I firmly believe that you do not need to be born an artist to create great photographs. In my view, landscape photography is largely a craft that can be mastered with practice. Noted black-and-white photographer John Sexton once said, “The only difference between me and my students is that I have made more mistakes than they have.” There’s a lot of truth in that statement. I shoot most of my images deep in the wilderness, but the lessons I’ve learned that I teach in this book are equally applicable whether you’re shooting sunset from the balcony of your home or shooting sunrise from the summit of a 14,000-foot peak. I hope that mastering the content of this book will give you the skills and knowledge you need to distill your own peak experiences into powerful images of the natural world.