9

Take a Walk on the Wide Side

It’s a wide, wide world out there. Certain subjects just cry out to be photographed in a panoramic format. Many of my favorite images from my “Sunrise from the Summit” project, in which I photographed sunrise (or sunset) from the summit of all 54 of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks, are panoramas. Something about that ultra-wide angle of view, sometimes as much as a full 360-degrees, captured the exhilarating, humbling, and awe-inspiring experience of being a tiny speck on top of the world. Many more-accessible scenes also fit the panoramic format. My favorite panoramas also include intimate landscapes taken inside golden aspen groves, sweeping vistas of sculpted sandstone canyons, and ultra-wide images of the Milky Way forming an arch that stretches from horizon to horizon.

The easiest way to shoot a panorama is to take a single frame and crop it to whatever aspect ratio works best for the subject. There’s no law that says that an image composed within a 3:2 frame must be shown with that same aspect ratio. However, there are two disadvantages to creating a panorama with only a single frame. First, your shot is limited to the angle of view of your widest lens. For my 16mm lens, that’s 97 degrees—wide, but not as wide as I often want. The second disadvantage concerns print size. Panoramas look good printed big, but the biggest print you can make is limited by the resolution of the single frame. The solution is to shoot a series of images, rotating the camera between shots so each frame overlaps the next, then stitch all the frames together with appropriate software. With this approach, it’s possible to create enormous panoramas—as much as 360 degrees wide—with tremendous resolution and sharpness.

Setting up a Single-Row Panorama

The simplest panoramas to create consist of a single row of images. The key to shooting a single-row panorama that can easily be stitched together is proper setup of the camera and tripod in the field. If you do a careful job there, the actual stitching of single-row panoramas is straightforward.

First, level the chassis, the part at the base of the tripod head where the legs join, by adjusting the length of the tripod legs. Check your work using the level built into the chassis (if you have one) or a handheld level. Note that leveling the camera is not the same thing as leveling the chassis. You need to level the plane on which the tripod head rotates as you pan across the scene. This is a crucial step; get it wrong, and a horizon that should be straight and level will look like a roller-coaster track. Next, level the camera left to right using the in-camera level or a level in the hot shoe. In the past it was also helpful to level the camera front to back, but stitching software these days is so good that this step is no longer necessary. I normally orient the camera vertically, which requires shooting more images to cover the width of the panorama, but also gives me higher resolution in the final image. If the closest part of your subject is 100 feet away or more, this completes the physical setup.

FIGURE 9-2 Panorama of Elephant Canyon at sunset, Needles District, Canyonlands National Park, Utah. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L III USM at 28mm. Stitched panorama, single row with seven camera positions, three-frame bracket set, two-stop bracket interval at ISO 100, images merged using Lightroom Classic’s Photo Merge>HDR Panorama utility.

Of course, the most interesting panoramas are typically those that include a nearby foreground. If your composition includes elements close to the camera, there’s another step required for setup: positioning the camera so it rotates around the nodal point of the lens. This step is necessary to prevent foreground elements from moving in relation to background elements as you rotate the camera, a phenomenon called parallax. To demonstrate this, hold up one finger and close one eye. Rotate your head back and forth while holding your finger stationary. Your finger will seem to move in relation to the background. This is because your eye is not centered on your head’s axis of rotation. Rotating the camera when its “eye” (the lens) is not centered over the axis of rotation (the center of the tripod head) produces a similar result. Trying to assemble a panorama with serious parallax errors will befuddle even the smartest stitching software.

FIGURE 9-3 Wolcott Mountain, Mears Peak, Peak 13,134, and lupine in the Mt. Sneffels Wilderness at sunrise, Colorado. Panoramas like this one, with close-in foregrounds, require use of a nodal slide to prevent parallax. Canon EOS 1Ds Mark III, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L II USM at 20mm. Stitched panorama, single row with six camera positions, three-frame bracket set, two-stop bracket interval at ISO 400, images merged using Lightroom Classic’s Photo Merge>HDR Panorama utility.

Rotating the camera around the nodal point of the lens requires purchasing a specialized panorama head. The Really Right Stuff Pano Elements Package that I currently use is shown in figure 9-4. The package consists of two parts: the nodal slide, on which the camera is mounted, and the panning clamp, which is mounted on the tripod head. The L-bracket bolted to the bottom and side of the camera was an essential but separate purchase. Once the panning clamp is leveled using the normal ballhead controls, you don’t need to touch those controls again. Leveling the panning clamp and using it to pan across the scene means the plane of rotation stays level regardless of whether the chassis is level. By design, leveling the panning clamp also levels the camera left to right. Using a panning clamp greatly simplifies setup. No more tedious adjusting of the length of each tripod leg to make the chassis parallel to the ground, then leveling the camera left to right as a separate step!

The disadvantage of using a panning clamp is that it forces the camera to be level front to back. That means you can’t point the camera up to include a tall mountain or down to include a deep canyon. The only way to ensure that tall mountains or deep canyons are included is to use a lens with a field of view so wide it will include the highest or lowest part of your subject with the camera level front to back, then crop off the excess from the opposite side of the image. For example, even with my widest lens, a 16mm, I can only look up 48 degrees or down 48 degrees (half the angle of view of the lens, since the camera is level from front to back). If your widest lens isn’t wide enough, you can’t shoot the panorama with the panning clamp.

There are two solutions to this problem. The first is to remove the panning clamp from the system and attach the nodal slide directly to the tripod head. This requires you to once again level the chassis by adjusting the length of the tripod legs. Although tedious, this approach lets you point the camera up or down and still eliminate parallax. You still need to level the camera left to the right. The second solution is to purchase a multi-row panorama kit and use it to shoot a single row with the camera pointing up or down. I’ll discuss multi-row panorama gear later in this chapter.

FIGURE 9-4 A Really Right Stuff nodal slide and panning clamp.

Finding the Nodal Point

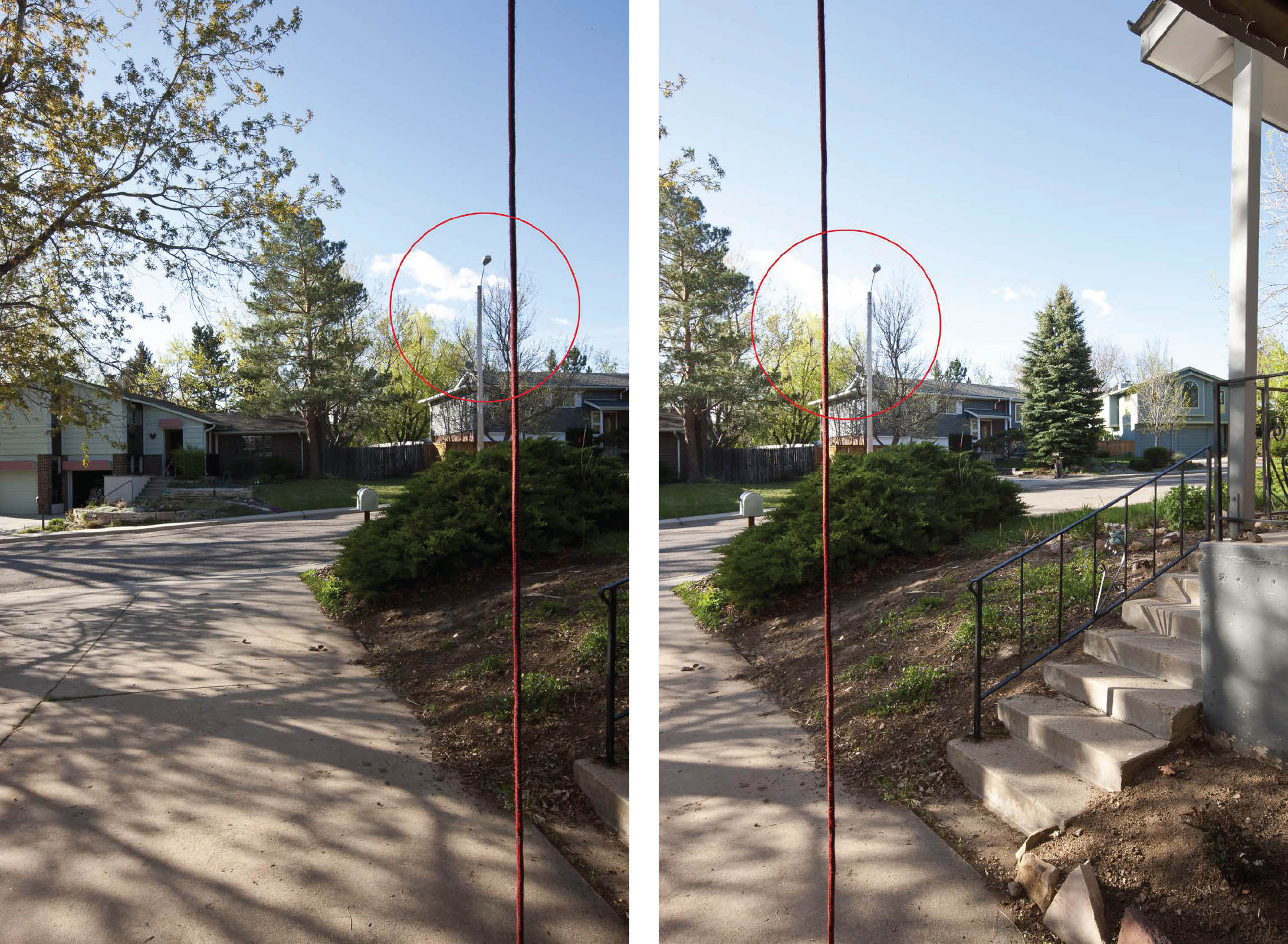

Here’s how to find the nodal point of your lens. First, create a situation in which some part of the subject is close to the lens, say, 18 inches or 2 feet away, while the background is at least 50 yards away. One easy setup is to tie a string to a branch or some other high support where you can see past the string to a well-defined landmark like a building or streetlamp. Hang a weight from the string to keep it from blowing in the wind. Now set up and level your camera as previously described. Adjust the nodal slide until you’ve positioned the center of the lens approximately over the axis of rotation of your tripod head. Now rotate the camera left to right. If the string shifts to the right in relation to the background, move the nodal slide forward (away from you as you look through the camera). If the string shifts to the left in relation to the background, move the nodal slide backward (toward you as you look through the camera). Find the position on the nodal slide at which the string remains stationary in relation to the background as you pan the camera from left to right. You only need to noodle over nodal points once: this is a one-time test that will not need be repeated so long as you use the same camera, lens, and L-bracket.

FIGURE 9-5 This pair of photographs demonstrates what happens when you rotate the camera with the axis of rotation passing through the camera body rather than the nodal point of the lens. Notice that the string appears to the right of the streetlamp in the image on the left, but to the left of the streetlamp in the image on the right.

If you’re working with a zoom, you should test several representative focal lengths, say, 16mm, 20mm, 24mm, 28mm, 35mm, and 50mm. You don’t need to test every millimeter change in focal length. You may find that you don’t have enough travel on the nodal slide to rotate a 70mm lens around the nodal point, but you’re not likely to be shooting panoramas with very close-in foregrounds with a 70mm lens because the depth of field of a 70mm lens extends only from 18 feet to infinity even at f/22. Longer lenses offer even worse depth of field. Write the results on a small card and put the card in your camera bag. I printed mine on an adhesive label and attached it to the nodal slide itself, then protected the label with a clear peel-and-stick laminate available at any office-supply store.

FIGURE 9-6 This pair of photographs demonstrates what happens when you rotate the camera with the axis of rotation passing through the nodal point of the lens. Notice how the string remains in the same place in relation to the streetlamp in both frames.

Camera Settings for Single-Row Panoramas

After perfecting your composition, leveling your camera, and positioning the nodal slide correctly, turn your attention to the camera controls. All controls should be on manual. Use manual exposure, manual white balance, manual ISO selection, and manual focus. Any change in exposure, color, depth of field, or focus point can make it impossible to stitch the images together. If possible, choose an exposure that will work for all frames in your panorama. If that’s not possible, use the exposure strategy I’ll discuss in the following sections. Compose generously, particularly with wide angles. Include more of the scene, on all four sides, than you will want in the final composition. When initially stitched together, the panorama will have scalloped edges. Although some stitching programs provide ways to fill in the scalloped edges, I prefer to include some extra image area when I compose, then crop off the excess.

Rotate the camera between shots so that each frame overlaps the next by about 30 percent. You don’t need to use precisely the same amount of overlap for each successive frame. However, I prefer to rotate the camera by a precise number of degrees using the scale on the panning clamp and the following table. It’s quicker to use the degree scale when the light is changing fast than it is to look through the camera as you pan to the next camera position. At night, when you can’t see much through the viewfinder and Live View on most cameras is useless, using the degree scale is essential. I shoot all panoramas from left to right because the degree scale counts upward when rotating in that direction. Be sure you set up the panorama so the degree scale reads zero at the first camera position. That simplifies the mental gymnastics you need to do to calculate the next camera position. For example, it’s easier to add 25 degrees repeatedly if you’re starting at zero (0°, 25°, 50°, etc.) than if you’re starting at, say, 13 degrees (13°, 38°, 63°, etc.).

FIGURE 9-7 A 200-degree panorama looking west at sunrise from the summit of 14,309-foot Uncompahgre Peak, March 2, 2010, Uncompahgre Wilderness, Colorado. I used the techniques I described in chapter 4 to determine the best day to shoot the full moon setting over Wetterhorn Peak at sunrise. Canon EOS 1Ds Mark III, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L II USM at 24mm. Stitched panorama, single row with six camera positions, three-frame bracket set, two-stop bracket interval at ISO 100, images merged using Lightroom Classic’s Photo Merge>HDR Panorama utility.

Stitching Panoramas

You can use Lightroom, Photoshop, and many other programs ranging from simple and cheap to complex and expensive to stitch your single-row panoramas together. The easiest and best solution at this writing is to use Lightroom. In the Library module, select the images you want to stitch, then choose Photo>Photo Merge>Panorama or right-click on any image and choose Photo Merge>Panorama. In the Photo Merge dialog box (figure 9-8), choose the projection you want to use: Spherical, Cylindrical, or Perspective. Spherical works well for multi-row panoramas and single-row panoramas shot with an ultra-wide-angle lens, particularly if the lens was pointed up or down. Cylindrical is usually best for single-row panoramas shot with moderately wide to telephoto lenses. Perspective often fails or produces a bizarre result. The preview will update as you click through the options, making it easy to decide which option is best for your panorama. The Boundary Warp slider will eliminate the scalloped edges of the panorama, but it must warp the image to do so. Checking Fill Edges will cause Lightroom to fill in the scalloped edges by inventing image content that is supposed to be a seamless continuation of the adjacent portion of the captured image. Check the result carefully; this feature is amazing when it works, but it can also fail dramatically. (As I mentioned earlier, I prefer to compose generously and crop off the scalloped edges.) Click Merge, and Lightroom will produce your stitched panorama. If you’ve done everything right in the field, the result should be perfect, with no stitching errors, such as odd, blurry discontinuities in the boundaries of objects that should be smooth. Better yet, your stitched panorama will be a DNG (Adobe’s RAW file format). That means it still has all the editing flexibility inherent in RAW images.

FIGURE 9-8 The Photo Merge>HDR Panorama dialog box in Lightroom Classic showing the settings I used to create figure 9-7.

Shooting and Processing High-Contrast Panoramas

If you’re shooting a very wide panorama, the brightest highlights are likely to be much brighter than the darkest shadows. In those situations, HDR will be the only viable way to capture good detail in both the shadows and highlights. I start by setting the best compromise exposure for the frame that will be the middle of my panorama (unless that frame includes the sun, in which case I exclude the sun when metering). Normally I use the exposure recommended by the camera as a starting point. As with all panoramas, I set all camera controls to manual. Then I pan the camera to the first camera position, which is always at the left end of the panorama. When the light hits, I shoot a three-frame bracket set with a two-stop bracket interval, so my exposures are, in order, 0, -2, and +2. After shooting the complete panorama, I check my histogram for each bracketed set to make sure I’ve got the detail I want in the highlights and shadows. If necessary, I’ll use exposure compensation to set the starting point for my bracketed set at -1 or +1 to ensure that my lightest frame has good shadow detail and my darkest frame has good highlight detail in each bracketed set. In extreme situations, I sometimes zero out exposure compensation and shoot a five-frame bracket set with a two-stop bracket interval to ensure that I have all the image data I need.

FIGURE 9-9 East and West Beckwith and Marcellina Mountain at sunset from knoll along the Lake Irwin Trail, Kebler Pass area, Gunnison National Forest, Colorado. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L II USM at 33mm. Stitched panorama, single row with six camera positions, three-frame bracket set, two-stop bracket interval at ISO 100, images merged using Lightroom Classic’s Photo Merge>HDR Panorama utility.

FIGURE 9-10 Turks Head and the Green River at sunset, Island in the Sky district, Canyonlands National Park, Utah. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L III USM at 20mm. Stitched panorama, single row with six camera positions, three-frame bracket set, two-stop bracket interval at ISO 100, images merged using Lightroom Classic’s Photo Merge>HDR Panorama utility.

After downloading the files to Lightroom, I select all the files in the panorama sequence and choose Photo>Photo Merge>HDR Panorama. Lightroom will combine all the images in each bracketed set into a 16-bit floating-point DNG, then stitch all the HDR DNG files into a panorama. Once again, the final file is a DNG RAW file, with all the editing flexibility of the RAW format.

If you’re shooting a 360-degree panorama, be sure to start the sequence by shooting the frame you’ll want on the left side of the finished panorama. You’re shooting a full circle, but the starting point still matters. By the time you work your way around the circle, enough time will have elapsed that clouds and sky color may no longer match up across the boundary between the first and last frames.

Lightroom often seems to have a mind of its own when stitching 360-degree panoramas. Rather than starting the stitch with the frame you shot first (the one you want at the left end of the panorama), it will pick an image from the middle of the sequence and start stitching from there. To solve this problem using Lightroom, you’ll probably have to drop the last image in the sequence, so that your completed panorama is really only 340 or 350 degrees, not a full circle. Another possible solution is to locate the first image you shot (the one that will end up at the left end of the finished panorama). Then locate the last image in the sequence (the one that will end up at the right end). In the final panorama, the right edge of the rightmost image should end where the left edge of the leftmost image begins. Crop the right side of the rightmost image so that no part of this image overlaps the left edge of the leftmost image. At this writing, Lightroom will only stitch images that have exactly the same pixel dimensions, so it will ignore the cropped image. To stitch together all the images, including the cropped one, you’ll need specialized stitching software. PTGUI is my current favorite.

FIGURE 9-11 Panorama of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison from Exclamation Point, with the Narrows on the left, flanked by the north and south Chasm View walls, and the Painted Wall on the right. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L II USM at 16mm. Stitched panorama, two rows, four camera positions per row, three-frame bracket set, two-stop bracket interval at ISO 100, images merged using Lightroom Classic’s Photo Merge>HDR Panorama utility.

Multi-Row Panoramas

Multi-row panoramas are stitched together from an array of images rather than a single row. For example, you might shoot four rows of images, with each row containing 10 images. The completed array would have four rows and 10 columns. Single-row panoramas are much easier to set up, shoot, and stitch together, so why would you ever want to shoot a multi-row panorama?

There are three main reasons. The first is to create images with mind-boggling resolution. The second is to shoot subjects that are both taller and wider than your widest lens can encompass. And the third is to shoot single-row panoramas in which you point the lens up or down without having to level the chassis by adjusting the length of the tripod legs. In conjunction with ultra-fast, moderately wide lenses, multi-row panorama gear also opens up intriguing possibilities when shooting the Milky Way, as I’ll discuss in the next chapter.

FIGURE 9-12 Milky Way panorama over Missouri Mountain and the Sawatch Range from the summit of Huron Peak, Collegiate Peaks Wilderness, Colorado. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF 50mm f/1.4 USM, stitched panorama, four rows, ten camera positions per row, 13 seconds, f/1.4, ISO 6400.

By stitching together multiple rows, you can create enormous files from which you can make huge prints with excellent quality. For example, I once had an assignment to shoot the backdrop for a trade-show booth that had to measure 10×10 feet at 300 ppi—which meant creating a file that was 36,000×36,000 pixels. I used a 200mm lens and shot nine rows with 13 images per row.

On another occasion I shot a Milky Way panorama from the summit of 14,003-foot Huron Peak (figure 9-12). I used a 50mm lens and a multi-row panorama setup to shoot four rows with 10 images each. The complete panorama measures 15,173 x 27,588 pixels—big enough to make a 51×92 inch print at 300 ppi.

FIGURE 9-13 My Really Right Stuff multi-row panorama setup.

FIGURE 9-14 Sunrise panorama of the south fork of Horse Canyon and the Maze from Brimhall Point, Maze District, Canyonlands National Park, Utah. I shot this panorama as a single row but used multi-row panorama equipment so I could point the lens down to include the bottom of the canyon. Canon EOS 5D Mark III, Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8L III USM at 21mm, stitched panorama, single row, four camera positions, three-frame bracket set, two-stop bracket interval at ISO 100, images merged using Lightroom Classic’s Photo Merge>HDR Panorama utility.

The Milky Way is a perfect example of a subject that is both wide and tall. At the right time of night, at the right time of year, the Milky Way makes a gigantic arch that stretches from horizon to horizon. A panorama showing the full arch can span an angle of 180 degrees left to right and 100 degrees vertically. Multi-row panorama gear lets you go wide both horizontally and vertically. Single-row panoramas let you go as wide as you want horizontally, even as wide as 360 degrees, but you are limited in vertical angle of view by the angle of view of your widest lens. Multi-row pano gear gives you the freedom to shoot as big an image, in an angular sense, as you want. It also gives you a fast, accurate way to keep the plane of rotation level while shooting a single-row panorama with the lens pointed up or down.

There are many ways to fudge the recommendations I’ve provided here. However, all of them come with the risk that the images will fail to stitch. You don’t want to blow some magnificent opportunity by using an unreliable shooting procedure. I prefer to use and teach methods that I know will work.

You can see my current multi-row panorama setup, which was made by Really Right Stuff, in figure 9-13. This hardware lets you shoot multi-row panoramas while keeping the plane of rotation level. As with a single-row panorama, you must rotate the camera around the nodal point as you pan from left to right if you have a close-in foreground. You can find the nodal points of your lenses for a multi-row setup using the same procedure you used for single-row panoramas. In addition to positioning the camera correctly from front to back using the nodal slide, you’ll also need to position the camera correctly from left to right, so the pivot point of the rotating base passes through the center of the lens. It will be easier to stitch together your multi-row panorama if you use precisely the same increment of rotation while panning the camera horizontally, as well as when you position the “pitch” of the camera (the degree to which it is pointing up or down) in between each row. For example, when using a 50mm lens and a full-frame camera set vertically, I pan the camera 20 degrees in between each frame and use a 30-degree pitch in between rows. I always shoot the bottom row first, from left to right, then the next higher row, again from left to right, and so on.

As with single-row panoramas, you must use manual exposure, manual focus, manual white balance, and manual ISO so that the component images will stitch together seamlessly.

Stitching software works by finding common points in the overlapping regions of adjacent images, then warping the component images until all the common points match up. Software’s ability to do this reliably has come a long way over the last five years. However, no program is invincible. For certain difficult stitches, you need high-end, specialized stitching software. Although features vary from program to program, in general these specialized programs have two major advantages over Lightroom. The first is that some programs let you define the grid in which the individual frames will be placed. For example, you can specify how many rows and columns the grid has, the spacing in degrees between images both vertically and horizontally, the sequence in which you shot the images, and the pitch of the first row. This information allows the software to create a rough layout of the images, which is particularly useful if some adjacent frames contain nothing but plain blue sky with no overlapping subject elements that the software can match up.

The second advantage of some advanced programs is that you can add control points manually. Control points, which always come in pairs, mark the identical point in the overlapping portions of two adjacent frames. For example, the summit of Longs Peak might appear on the right side of one frame and the left side of the adjacent frame. By adding control points to the top of the summit cairn in both frames, you’re telling the software to make those two points match up in the final panorama. If you can add three or more pairs of control points to each pair of images, you’ve given the software a good idea of how to match up the various subject features. The software does its best to add control points automatically, but the ability to add additional control points manually makes it possible to complete difficult stitches that might otherwise require hours of tedious retouching by hand.

Learning to shoot and stitch panoramas from multiple frames will open up a new world of photographic possibilities. No longer are you limited to seeing the world through the rectangular frame defined by your viewfinder, with its rigid 2:3 aspect ratio. That view, as pleasing as it may be, is only the starting point in your search for the most evocative possible composition. Take a walk on the wide side, and you’ll never again be content to see the world in just one way.