01

The Client Perspective: Strategy, Cost and the Long-Term Value of Asset Information

Introduction

In structuring this Handbook, it was important to think carefully about how best to balance the significant business needs of firms already employing a BIM Manager or Coordinator with those that have little or no BIM capability.

The starting point for Building Information Model management is the process of aligning your design technology strategy with not only the goals of your firm, but also those of your clients. This chapter captures why BIM is valuable to clients and how to formulate the BIM Strategy with added relevance to the client’s own decision-making and asset management strategy.

The key coverage of this chapter is as follows;

- Building Information Modelling – a definition

- Where and why should we do BIM?

- BIM and Cost Analysis

- Defining BIM Objectives.

Building Information Modelling – a Definition

In order to establish a common frame of reference, we begin by considering the formal industry definition of Building Information Modelling.

In the UK, the Construction Project Information Committee (CPIC) is a UK advisory group that has been a key participant in the development of common industry processes for BIM. Its BIM definition paraphrases that of the US National Building Information Model Standard Project Committee, stating:

‘Building Information Modeling (BIM) is a digital representation of physical and functional characteristics of a facility. A BIM is a shared knowledge resource for information about a facility forming a reliable basis for decisions during its life-cycle; defined as existing from earliest conception to demolition’. 1

Why and where should we do ‘BIM?’

Although we shall unpack this lengthy definition into simpler principles in the next few chapters, we shall now consider BIM in the light of the client’s strategic priorities. Instead of repeating and refining existing definitions, this book begins by responding to the question that is often overlooked: ‘Where and why should we do BIM?’

In order to answer this, we should turn our attention to the overall purpose of innovation as a means of business improvement. Typically, new technology is adopted to deliver enhanced value with greater efficiency. So, BIM strategy should provide greater value to the client and your organisation as well as improving project efficiency.

In simple terms, BIM allows users to share project and asset information by mapping that data onto 3D representations of building components that reside in the model. Combining shared models aggregates the mapped data so that users can review, sort and filter the combined and comprehensive inputs of all project participants.

For instance, by selecting a plant room space in the plan, users can review its dimensions established by the architect, the air flows needed to maintain the required room temperatures (known as set points), the boiler’s clearances as set by the building service engineer and the self-weight assigned to the same equipment by the structural engineer.

The value of BIM is in providing a graphical environment in which all of the specialised data for any area or element in the proposed building is immediately accessible to all users.

Of course, as with any other business system, information loses value when it becomes inaccessible, out of date or erroneous. This is true of all collaborative data development Yet, considering the many other databases that businesses employ, such a truism does not make the case for not using them.

Considering the Client’s Long Range Business Goals

While it’s always useful to focus on project-specific goals, doing so to the neglect of the client’s long–range business strategy is unwise. Such an approach places undue emphasis on the relatively short-lived value that can be extracted during the project lifecycle, whereas it is far better to also tap into the long-term priorities of both current and prospective clients.

The other consequence of pursuing a solely project-based approach to BIM is that it becomes overly focused on the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of each process rather than why a particular output is needed in the first place. It is all too easy to concentrate on the mechanisms involved in delivering every imaginable kind of BIM output without first determining which deliverables are of sufficiently compelling value to both the project and client.

The Importance of relating BIM strategy to Client strategy

If BIM is not aligned with the client’s business priorities, the strategy for implementing it will become skewed towards just improving internal and collaborative efficiency, instead of maximising its overall effectiveness on behalf of the client. Instead, BIM strategy should, within the constraints of available time and resources, aim to maximise the value of the technology for both the client and the project team.

Alignment with Client asset Management strategy

To this end, consulting the client’s asset management strategy is a useful starting point for developing an all-encompassing BIM strategy.

Consider a major food retailer that sets a goal of opening 150 new branded high street stores across the country over the next three years. While major project-related costs will be incurred by that decision, associated with that corporate priority is the significantly higher long-term impact on operations, maintenance and disposal costs.

It is because of the relatively higher costs incurred in use and beyond the immediate project lifecycle that a comprehensive BIM strategy must reflect the asset management strategy of the client. Note that this is very different from attempting to consult the client’s own BIM strategy (assuming that one exists).

As an example, consider this excerpt from the UK’s Network Rail Asset Management Strategy. The Executive Summary explains: ‘Network Rail’s commitment to its customers is enshrined in a Promise to deliver the Timetable, so that trains run safely, punctually and reliably – now and in increasing numbers in the future. Asset Management supports the delivery of the Promise by planning, delivering and making available an infrastructure that supports the current and future timetable – safely, efficiently and sustainably.’2

It is important to note that the stated approach is in support of the rail infrastructure operator’s business commitment. The emphasis is on achieving infrastructure availability capable of supporting the Network Rail’s promise to deliver current and expanding future timetable requirements. This goal is qualified by the importance of maintaining safety (which is reiterated), efficiency and sustainability. Later in this document, there is also recognition that ‘a significant improvement in our asset management capability is required to live up to this commitment’.

So, it would be neglectful for the design team to adopt a strategy that bypasses Network Rail’s asset management goals.

Further along in the Network Rail Strategy document, the importance of the asset management strategy is clarified: ‘Asset management of the railway infrastructure is fundamentally about delivering the outputs valued by our customers and funders and other key stakeholders, in a sustainable way, for the lowest whole life cost.’

So, in this case, whatever your internal priorities for BIM, the client’s stated asset management goal, like this one, should shape your long-term BIM strategy. Therefore, one of the client-aligned BIM goals for an infrastructure contractor working on Network Rail projects might read: ‘To provide BIM outputs that enable key stakeholders to ascertain readily the impact on asset value of our design and construction alternatives and determine the lowest sustainable whole life cost as design proceeds.’

As another example, consider a Housing Association that has implemented a strategic goal that aims to ‘identify a five per cent increase in the overall net present value (NPV) of our property asset base, extracting maximum value for those assets whilst supporting a diverse portfolio to ensure mixed communities.’

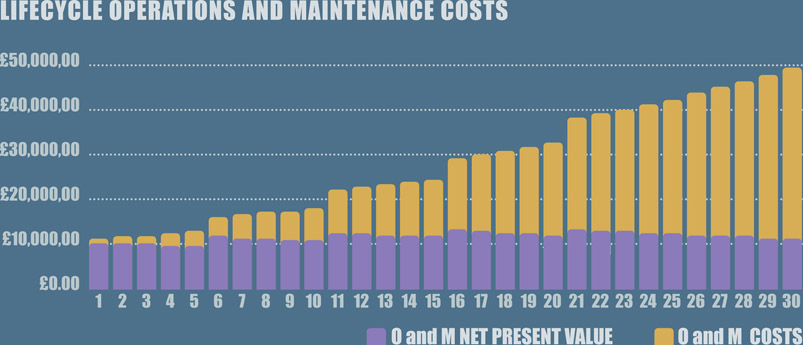

Net present value takes inflation into account by discounting costs incurred over the building’s lifecycle in order to price them in today’s money. In the graph below, the annual increases in operations and maintenance (O and M) costs are depicted by the orange bars, while the purple bars represent their respective net present values.

Figure 1.1

Lifecycle operations and maintenance costs

Given that the Housing Association’s goal is a five percent overall increase in net present value, this could be achieved by either gross rental increases, or by reducing the operations and maintenance costs by the same amount.

Here is a corresponding BIM goal that would garner their interest: ‘By means of BIM analysis, to optimise sustainable design strategies in order to deliver a consistent five percent reduction on baseline O and M lifecycle cost projections’. Once achieved, this forms a far more likely basis for repeat business with the Association than just streamlining the drawing production process.

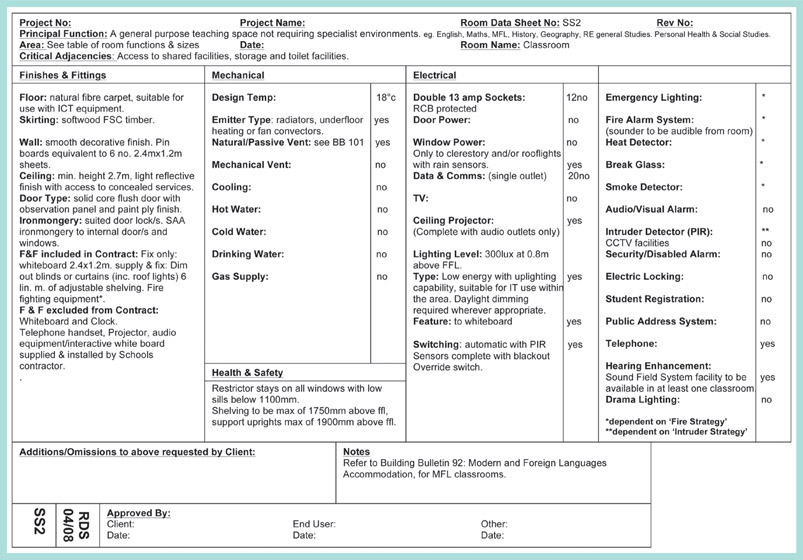

As a final example, the Education Funding Agency has implemented a set of non-statutory area guidelines for mainstream schools. In furtherance of this guidance, it has also issued a spreadsheet-based Schedule of Accommodation reporting tool for ensuring that the spaces, as designed, fall within the area ranges (based on group sizes) specified in Building Bulletin 103.

In addition, standardised area data sheet (ADS) codes are used to classify the wide variety of classroom types and room functions.

Figure 1.2

Education Funding Agency’s Schedule of Accommodation tool.

In alignment with this official guidance, the corresponding BIM goal would be: ‘To facilitate the review of design options by automating the production of area data sheets from BIM and thereby significantly reducing the requirement for manual data entry to complete standardised Schedule of Accommodation reports.’

Why should asset Cost considerations be important to your BIM strategy?

The costs associated with a proposed asset are key to the client’s determination about whether it will meet their performance requirements. In particular, whole life costing seeks to provide a consistent basis for comparing the long-term impact of alternative proposals that require different cash flows over different timeframes.

If an organisation’s BIM strategy does not seek to facilitate these long-term asset cost comparisons, it will miss the opportunity for using the technology to facilitate and influence the client’s investment decisions. BIM is a technology that provides for direct integration of financially valuable data with design or construction proposals. A good example of this capability is the automatic production of Gross Internal Floor Area schedules from the model.

In respect of long-term feasibility, it is important to distinguish initial capital expenditure (CAPEX) from ongoing operating expenditure (OPEX). To consider the former without regard to the latter would lead to short-sighted investment decisions that have no long-term viability.

One method of reviewing both CAPEX and OPEX involves assessing the Whole Life Cost including Life Cycle Cost. The components that together comprise Whole Life Cost are shown in fig. 1.4

Figure 1.3

Sample school area data sheet (Courtesy of Cornwall Council)

Whole Life Cost predictions are crucial to the process for gaining financial authorisation for a building project, as it proceeds through distinct decision-making stages, known as gateways. At these gateways, stakeholders participate in reviews to assess the business case and technical feasibility of a project before approving further work.

It’s important to remember that money tied up in a construction project, or in operating the resulting asset, could have been profitably invested or lent elsewhere. Therefore, it is important for businesses to evaluate the potential returns on those investment alternatives that are being rejected in favour of a particular scheme. As a consequence, the importance of assigning monetary value to the significant resources expended in producing or maintaining an asset cannot be understated.

In order to assign costs to projects through BIM, elements in the model are classified by a set of common building functions, such as roof, enclosure and structural frame. By means of export to a compatible database format, the model’s data structure provides comprehensive schedules of quantities and can also be embedded with historical cost data as a starting point for O and M cost estimates. As the designers update their models with alternatives, the schedules and estimates will automatically update to provide a faster means of comparison with the cost plan.

BIM and Cost analysis

the Building Cost Information Service (BCIS) of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors provides the elemental Standard Form of Cost analysis5 (SFCA) as the definitive industry-wide standard for cost planning. In accordance with the New Rules of Measurement 2, the document assigns the different components of building design to 14 categories of element definitions for costing purposes. In each case, the SFCA document clarifies the rules and units of measurement.

A logical consequence of these definitions is that if quantities derived from our models are not structured in accordance with these definitions, they will not facilitate useful comparison.

So, a consequent (and often neglected) goal of a design or construction firm’s BIM strategy would be: ‘To consistently classify models and quantities derived from them in alignment with industry-standard elemental cost definitions, thereby facilitating a significantly more detailed and useful response to the Client’s Cost Plan reviews.’

Figure 1.4

Whole Life Cost breakdown – ISO 15686-54

Defining BIM Objectives

There is also a further need to break each goal down into several short-range objectives that allow us to evaluate the trajectory for success. These milestones should be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely (for which the business acronym is SMART). They punctuate the journey towards achieving each strategic goal.

For instance, it is of immense value for client decision-making to be improved by BIM through transparency about costs (both project and whole life). This would be the impetus for a number of BIM objectives:

- ‘To automate the classification of model elements for industry-standard cost analysis in accordance with the BCIS Standard Form of Cost Analysis (SFCA) for all projects by year 2 of our BIM implementation programme.’

- ‘By year 3, to develop in conjunction with cost consultants a reliable method of applying BCIS pricing to BCIS structured schedules of quantities derived from BIM, thereby allowing stakeholders to readily compare the cost of design alternatives against the Cost Plan.’

Achieving these objectives will involve tactical choices discussed later in this book. Nevertheless, the proviso for achieving collaborative objectives is a well-defined contractual arrangement that ensures that all project participants understand the terms under which this information is being shared.

BIM strategy and the Long-Term Value of asset information:

Value can be understood as the economic benefit that is derived from a product or service. The key benefits of asset information are outlined in PAS-55, the Publicly Available Specification for the Management of Physical Assets.

This accepted UK Standard explains of asset data that:6

‘Examples of information to be considered include the following:

- Descriptions of assets, their functions and the asset system they serve

- Unique asset identification numbers;

- Locations of the assets, possibly using spatial referencing or geographical information systems

- The criticality of assets to the organisation;

- Details of ownership and maintenance demarcation where assets interface across a system or network of assets

- Engineering data, design parameters, and engineering drawings

- Details of asset dependencies and interdependencies

- Vendor data (details of the organisation that supplied the asset)

- Commissioning dates and data

- The condition and duty of assets

- Condition and performance targets or standards

- Key performance indicators

- Asset related standards, process(es) and procedure(s)’.

In particular, it also states that: ‘asset management information should be capable of enabling an organisation to:

- Make life cycle cost comparisons of alternative capital investments

- Determine the total cost of maintaining a specific asset(s)/asset system

- Identify expiry of warranty period and warranty

- Comply with statutory and regulatory obligations

- Obtain/calculate asset replacement values

- Determine the end of economic life of assets/asset systems, e.g. the point in time when the asset related expenditure exceeds the associated income.’ 6

Therefore, in respect of these capabilities, another key goal of BIM strategy would be defined as: ‘To develop and demonstrate the capability to deliver asset information from BIM in a structure compatible with PAS-55 compliant industry-standard asset information management processes.’

The reason for defining the goal as being to ‘develop and demonstrate the capability’ is that the delivery of such information would generally only make sense when it applies to an agreed contractual obligation, positions the firm to win significantly more business or represents added value for which the client will pay a premium.

Checklist for Formulating your BIM Strategy:

In formulating your own BIM Strategy, take a look at the headline goals in the asset management strategies of major clients and ask yourself the following questions.

- How do your current goals for design and BIM align with your client asset management strategy?

- Can you describe the asset management strategy of your firm’s largest client? Where does that information exist?

- Where and how have cost planning and asset information been introduced as key goals of your BIM strategy?

- Beyond graphical and textual output for design and construction, what initial considerations about the long-term value of the data from BIM could you provide for the client at handover?

- How will the client be able to sustain the value to their own business of the data that you intend to hand over?

- Has the client adequately planned resources for updating that data over the life of the facility?

- Have you investigated which software file formats will ensure your project data is readily accessible and appropriate to your client’s short- and long-term business requirements?

Conclusion

We have reviewed the importance of formulating the firm’s BIM Strategy from the standpoint of your client’s own strategy. This client focus should be balanced with internal and collaborative project goals for BIM. Nevertheless, if the strategy does not recognise the client’s priorities, it will fail to encompass the full business potential of BIM.