06

Managing the Mandate: The BIM Level 2 Environment

Introduction

Although the Levels of BIM Maturity were outlined in Chapter 4, it is important to address the impact on the organisation as it seeks to adopt BIM Level 2. In this chapter, BIM Level 2 is explained in terms of managing the organisational change and implementation plan required to deliver it.

This includes:

- What does BIM Level 2 mean for my organisation?

- BIM Manager’s essential project delivery task list.

What does BIM Level 2 Mean for my Organisation?

The title of this section is probably the question that the construction industry asks more than any other, in terms of the mandate for fully collaborative 3D BIM on all centrally procured UK government construction projects. In order to understand the impact on the organisation, it is important to consider the key internal environment factors that will be affected. These are:

- Organisational culture

- Management

- Organisational structure

- Assets

- Financial strength

- Human resources.

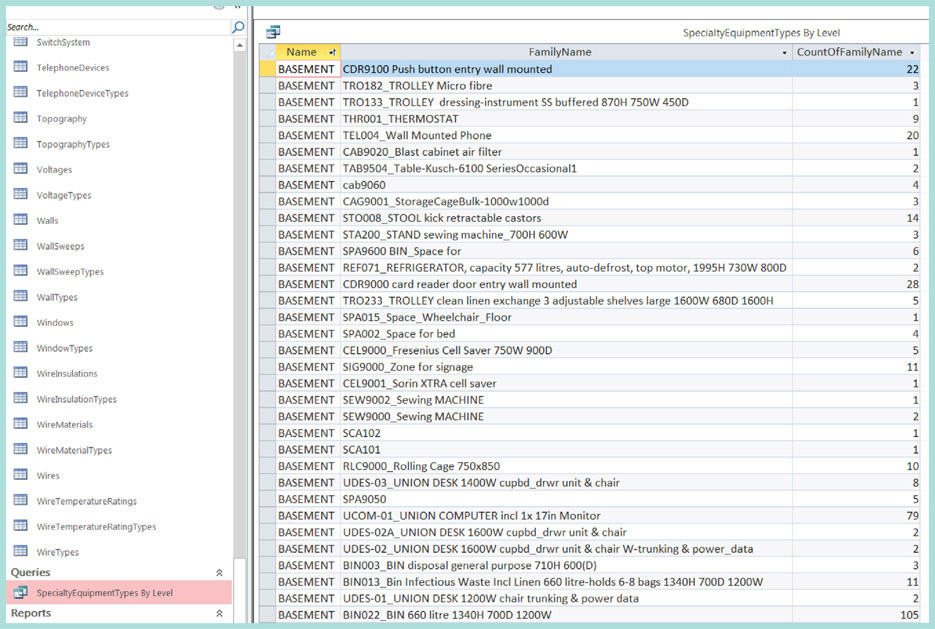

Culture has been described as a ‘system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs that show employees what is appropriate and inappropriate behaviour.’1 In respect of adopting new initiatives like BIM, the organisational culture must beget an atmosphere of trust, which means relying on the honesty and integrity of others, especially the leadership. Unlike business as usual, multi-faceted technologies like BIM will pervade every aspect of design and construction practice; their successful implementation will therefore require the cohesive effort of the entire company. If trust in the leadership is lacking, there will be misgivings about any managerial assertions about the smoothness of changing over to BIM and whether transitional arrangements will be sufficient for the level of responsibility accepted by those adopting the new technology. Organisational culture influences whether staff respond to management initiatives with enthusiasm, indifference or complete apathy – is typically informed by past experiences. Whether good or bad, these can make or break future attempts to deploy new technology. As an example, let us describe a situation in a hypothetical organisation, where some previous IT implementations, including a sophisticated project data management solution, have foundered badly due to insufficient investment in configuration, professional support and training. Despite this, end-users might still have unofficially borne the brunt of blame for the failure of the new systems. On that basis, the same end-users would be justifiably wary of unqualified managerial optimism about realising the benefits of BIM. As a means of engendering trust, management should announce their plans for BIM only after they have factored professional support, training and realistic staff development timescales into the overall impact of implementation. They should establish a monthly office-wide forum for raising concerns and agreeing solutions in relation to the new technology. A BIM ‘suggestion box’ would also provide a means for staff to air issues anonymously. This kind of interaction would help to develop genuine and collective consensus and trust. Consider the below example of exporting the data in the 3D model of a major hospital to a Microsoft Access database. The resulting equipment database was sorted by level, filtered and enumerated. This demonstrates that, beyond 3D, models can be used to embed and exchange commercially valuable information about every aspect of the design, construction and operation of built assets in a format that is spatially organised and also searchable by normal database queries. Figure 6.1

Database export of the 3D model This is of immense value in helping to achieve major improvements in both inter-departmental and inter-organisational efficiency. Therefore, BIM warrants the full involvement of senior management in committing firm-wide time, effort and other resources to its successful implementation. The first step is for senior management to arrive at a consensus on the reasons that BIM Level 2 is an important corporate goal, how it fits into the overall corporate strategy, and the timescale and criteria for monitoring how it is achieved. What are the risks involved (including that of doing nothing)? This consensus should be the basis for defining the firm’s strategic aims for BIM. For example, they might include:

The organisation’s vision statement is an important outcome from this consensus on BIM strategy. The vision should encapsulate the ideal positioning in the competitive business environment that should result from your strategic efforts.

Here are a few examples of BIM vision statements, some of which align closely with the above-mentioned aims:

The vision must be articulated regularly and consistently by senior staff as a set of clear long-term strategic goals combined with the consequent measurable objectives and key performance indicators that need to be achieved (see Chapter 1). Once the goals have been clarified, the management team should commission the BIM Sponsor, in conjunction with an external consultancy with a proven BIM implementation track record, to develop a documented assessment of the current state of the firm and its readiness to implement BIM. This would include:

A BIM implementation plan should be developed by the BIM Sponsor and BIM Champion (see Chapter 3) after reviewing the readiness assessment. In particular, the plan should contain the following elements:

The implementation plan – with a realistic budget and schedule – should be reviewed by the directors and either rejected, approved or fine-tuned to the organisation’s needs. Approval of the implementation plan should trigger the next step. Before implementation proceeds, the BIM Champion must be able to instil firm-wide confidence in the technical aspects of the BIM approach. This can only be achieved by thorough training and taking sufficient time to ensure that this pivotal individual is able to guide the production of high-quality deliverables through BIM. The BIM Champion should be tasked with developing a small pilot project to constructional detail. This is because the production of large-scale general arrangement drawings from BIM is relatively straightforward, while most approaches to incorporating detail at smaller scales involve a balance between the addition of ever finer 3D model detail and the embellishment of derived orthogonal views with extensive 2D drafting and annotations. Thus, one of the biggest challenges for new implementations is the development of efficient methods for increasing the detail and information stored in BIM as the project deliverables progress to construction documentation. On this basis, there should also be a contractual mandate for the BIM implementation consultant to explain how best to combine model and 2D detailing. This would involve a live demonstration of previous models containing convincing examples of useable construction documentation. An early business-wide multi-level awareness campaign should be conducted by the BIM Sponsor and BIM Champion (with the help of external consultants) to promote the business-wide understanding of BIM and its implications for staff. This should never be conducted without first addressing team leaders confidentially in order to gauge their concerns. The firm-wide briefing should explain the corporate vision for BIM at all levels by answering questions like:

For successful orderly change, careful management is required. To this end, the firm’s entire organisational structure should be audited in line with the corporate vision for deriving benefits from BIM. This includes those taking the key role of marketing the benefits of BIM to prospective clients through bids and events. BIM is not simply a high-powered 3D drawing tool. If used properly, it will affect every aspect of the firm’s project data management process. As an example, part of the BIM Protocol used on projects might include an agreement to embed design criteria in the model so that it can be used to develop elemental cost analyses. Normally, these criteria would be added in the form of specification data, requiring the expert input of senior project staff. If this input is not by direct interaction with the model, the team must factor in the time required for technician-level staff to transpose the information from a different format. The time-saving advantages of BIM for cost analysis will not be achieved if considerable time is lost in doing this, or if the

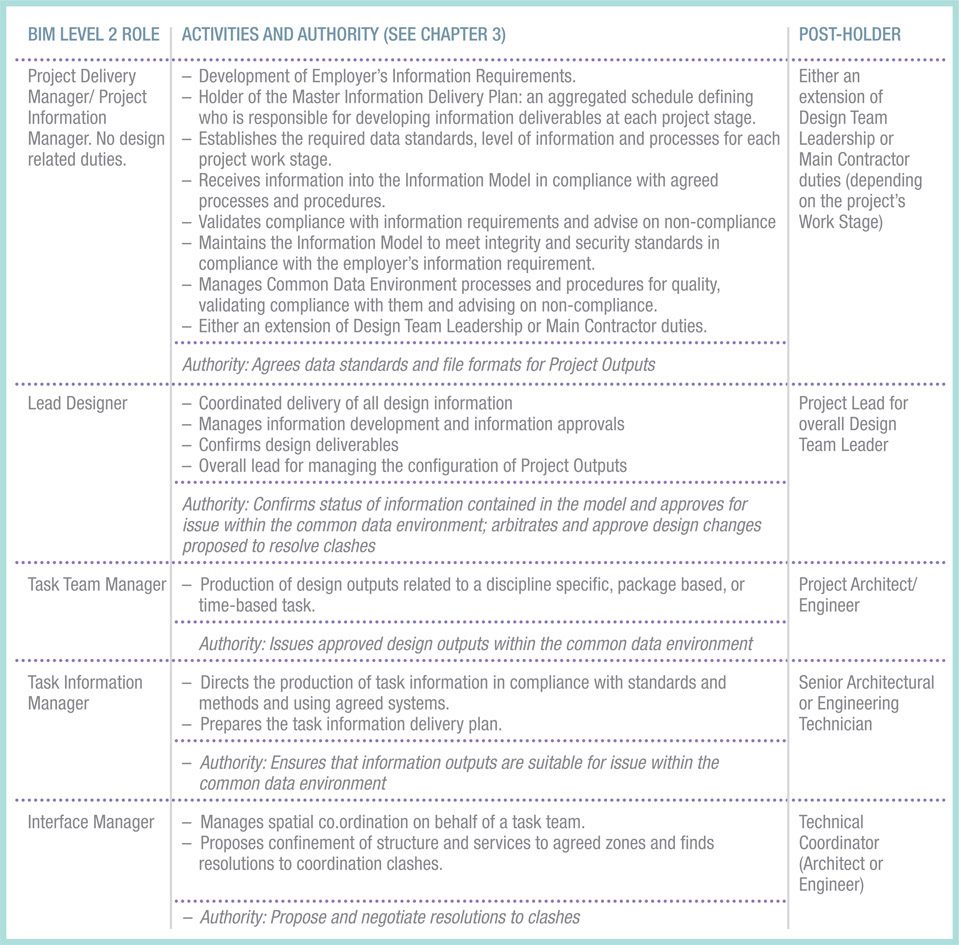

transposition to BIM is only partial. Equally, the benefits of multi-disciplinary coordination in BIM will not be fully realised by a project team that fails to utilise the federated model in their design review sessions. It is important to recognise and celebrate early successes and long-term wins. Recognition by management of exceptional effort (whether by an intranet posting, or a firm-wide email) boosts morale with the same kind of endorsement that should accompany the accomplishment of other major initiatives. It also reassures staff with the knowledge that achieving each objective of the implementation is, indeed, a significant corporate milestone. For most design and construction organisations – and for SMEs in particular – there are justifiable concerns about taking on dedicated BIM staff. As a word of reassurance, there is a need to distinguish the required BIM Level 2 role (see PAS-1192-2) from the post-holder likely to perform it. As can be seen from the table on the previous page, although the BIM roles may appear new and may involve substantial training, they correlate well to the traditional positions identified in the right-hand column. While larger firms can afford to employ a dedicated BIM Manager, SMEs, in contrast, will have to answer important questions about how these roles can be facilitated by the organisational provision of model set-up, administration and technical support. Most design and construction staff can solve many basic CAD issues without recourse to technical assistance. Typically, if a stand-alone CAD file is corrupted and fails to open, only a single user is affected. By themselves, most users will probably be able to restore the last back-up in a matter of minutes. Restoring an earlier iteration of the multi-user model in BIM requires more care, time and expertise and will affect everyone working on it. For smaller organisations, the initial cost-effective response to this added expert requirement would be to address BIM support by developing it as a shared organisational capability (see Human Resources below). The BIM Champion should field immediate queries about software malfunction and using different functions to develop both interim and formal project deliverables. This is known as first-line support. As a back-up to this role, a contract for telephone support from the software reseller would provide a means of escalating more challenging issues. However, it is important to check the proposed terms and conditions of contract regarding what is accepted as a genuine support question, as opposed to matters that might be declined as arising from a lack of basic end-user training. Even if a firm has the means to hire a full-time BIM Manager, it makes sense to ensure that, beyond support alone, part of the prospective role is to document BIM project procedures and to produce training materials for all levels in the organisation. Candidates for the position should be able to produce samples of their own clear and consistent BIM documentation and training material. Setting up BIM projects consistently and publishing documented support responses provides the opportunity for staff to search for answers themselves and, on simpler issues, become less dependent on the BIM Champion. For a while, it may also forestall the need to hire a full-time dedicated BIM Manager. While this approach has its advantages, the main drawback is that the initially enthusiastic BIM Champion may become disillusioned by the extra workload of combining existing duties with an office-wide BIM support role. At some point, it may be necessary to review staffing policy in order to provide project teams with dedicated BIM support. Formally, an asset is defined as ‘a useful or valuable thing or property owned by a person or company, regarded as having value and available to meet debts, commitment, or legacies.’ Oxford English Dictionary Assets can range from elements of the physical corporate environment to an organisation’s intellectual property. While the role of physical assets is fairly well documented, there are intangible assets that are critical to implementing BIM. Some of these are referred to as Organisational Process Assets and include:

Part of the role of management is that of an organisational curator. This involves not only cataloguing and archiving standard processes as templates for the entire firm, while reviewing key challenges; it also includes holding events and meetings that publicise the value of these assets to all staff. For instance, a BIM ‘Lessons Learned’ session should be held at the end of each project work stage to review the execution plan and to document:

This should be followed up with a review of existing policies and procedures and an office-wide presentation on how these policies will be amended in the light of these issues. This factor is critical. If an organisation is severely cash-strapped, it must address those challenges with short-term measures to return it to a moderate level of profitability before embarking on its strategic vision for BIM. (It might also prove hard to whip up morale for a new initiative from staff who think that they are one pay day away from redundancy.) In contrast, financial strength will not only buffer the cost of implementation, it can wield considerable external influence. Despite internal misgivings about the impact of implementing BIM, a wealthy prospective client or supply chain partner that mandates the use of BIM will not be ignored. While paying due regard to his or her existing workload – and with the assistance of external training development expertise – among the BIM Champion’s responsibilities would be to provide expert input on staff development for BIM. This involves imparting advice on the best available learning and training options. Learning differs from training by imposing greater self-study responsibility on the participant. Part of the BIM role involves developing internal learning modules (ranging from one-page documents to a series of demonstration videos) tailored to the organisation’s intended use of BIM. These should cover everything from ‘How do I set up a new set of models for a healthcare project?’ to ‘How can I customise 3D elements of furniture, fixtures and equipment, tag them on drawings and create a schedule of those used in my project?’ It’s important to reiterate that the purpose of implementing this tailored training is to achieve the benefits of BIM through organisational upskilling and without necessarily incurring the cost of a full-time dedicated BIM Manager. This approach does incur the cost of course development for which there should be a budget. If this is outsourced, it will involve the cost of an external expert tasked with developing the tailored training plan. When taken together, this means that, at some point, all organisations wanting to adopt BIM must accept that human resource development costs are involved. That is, expense will be incurred either through developing tailored learning content to establish organisational competence; through hiring a dedicated BIM Manager to develop procedures, oversee implementation and provide on-going support; or through hiring external expertise to deliver standard training on basic functionality and to devise tailored course modules that ensure staff use BIM in accordance with organisational and project standards. If you do opt to develop in-house learning content, the next step is to determine the modules that are best suited to each different staff role and the ideal sequence and schedule (i.e. learning path) for working through them. Managers should be tasked with ensuring that those directly reporting to them complete their assigned modules as part of their annually reviewed Personal Development Plans. It is important to emphasise that the firm-wide implementation of this training requires the highest level of managerial support (as described in Chapter 3). The introduction of BIM can often arouse employee anxiety over both its presumed complexity and its potential to eliminate the expertise by which their existing professional experience is distinguished. The reality is that much of the coordination process is still performed in 2D. Moreover, 3D coordination still relies as much on the knowledge and visual scrutiny of experienced technical coordinators as it did before the advent of BIM. So, while checking for clashes can be automated, reviewing the adequacy of safety clearances and maintenance access for services and equipment will involve experienced technical coordinators who can tour the model, check dimensions and add mark-ups of the changes that need to be made. Instead of commissioning vast swathes of basic software training, what is more appropriate is the gradual introduction of focused training sessions that concentrate on those functions immediately relevant to both existing roles and the extension of them via BIM. For instance, training technical coordinators on every aspect of using 3D coordination review software (such as Autodesk Navisworks®, Tekla BIMsight® or Bentley Project Navigator®) is nowhere near as effective and efficient as showing them the basics of how these tools can enhance the work that they already do. For example, coordinators should learn how to:

BIM Manager’s Essential Project Delivery Task List

At this stage, it’s worth summarising the essential tasks that the BIM Manager should be expected to undertake:

Organisational Culture

Management: Developing a Consensus to inform your Strategic aims for BIM Level 2 Implementation

Reminding staff of the Vision

creating a Readiness Assessment

Creating an Implementation plan and Organisational Structure

Developing the BIM champion to power user level

Launching an awareness campaign across the business

Change Management

Remembering to celebrate success

Organisational Structure

What extra roles and resources will we need?

Building the organisational BIM capability

Handling end-user support

Assets

Financial Strength

Human Resources

Where possible, use focused training to extend existing roles

Conclusion

There are significant implications for adopting BIM Level 2 for the first time. It is important to plan the implementation carefully and address the impact on the whole organisation.

These are summarised in terms of:

- Organisational culture

- Management

- Organisational structure

- Assets

- Financial strength

- Human resources.

We have seen how each of these will affect how BIM is deployed. The choice of whether internal expertise is developed by informal internal effort, a dedicated manager or external expertise is a critical one. If you do opt for a dedicated manager, the above task list should be useful in establishing the scope of required duties.