Laws and Internet Privacy

Abstract

This chapter talks about what information you should and shouldn’t be storing online.

Keywords

Facebook; Challenge questions and answers; Online

Information in This Chapter

• How much information you should share with companies?

This chapter talks about how the Internet and the various laws around the world apply.

The law and changing technology

When it comes to technology, in general, the legal system (regardless of what country you are in) can’t keep up. New services and technologies change at a much faster pace than the legal systems can keep up with. Often, they end up being laws that directly conflict with technology, or we could even end up with different laws, some allowing the new service or technology and others that prohibit it.

When it comes to data privacy and specific government regulations, there are often large gaps between when a specific technology becomes available and when laws come into effect regarding that technologies use. In the United States, for example, there are no laws that tell companies what they are allowed to do with personal information that they collect from customers online even though companies have been collecting information from customers on the Internet for over 10 years. There are a variety of laws that have to do with electronic communications such as the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA, codified at 18 U.S.C. §§ 2510-2522) that you can read the text of at http://basicsofdigitalprivacy.com/go/ecpa. This law is one of the primary laws used to govern electronic communications, which includes Internet access, but it was written before what we consider to be the Internet of today was created.

PRISM

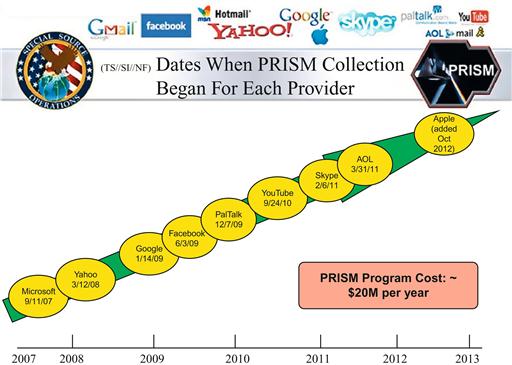

In the spring of 2013, it was revealed that the US National Security Agency (NSA) Internet has a monitoring program called PRISM. With this system, the NSA is able to monitor a huge amount of information and much of that information can be stored forever. With the NSA's PRISM program, the basic goal was to gather Internet communications data of anyone who isn’t inside the United States in an attempt to figure out who is talking to terrorists so that they can use the information gleaned from this work to stop a future terrorist attack.

This means that the NSA has data collectors on the Internet backbones around the world. These Internet backbones are simply fiber optic cables, which run from datacenter to datacenter moving everyone's Internet traffic around the world. These fiber optic cables in many countries do not belong to the government but instead to private companies. The NSA would have needed to get the companies who own these backbone lines to work with them to give them access to the data. For the countries that do regulate Internet access within their national borders and where the countries' government owns the Internet links, the NSA would need to have a deal in place with that government that would allow it to monitor all this Internet traffic. The question becomes why would another country's government want to provide the NSA access? There could be a variety of reasons, all of which one can assume would be classified by both governments, those we can assume that helping the NSA would carry some favor with the US government at some point. The assumption exists that a data sharing policy would be in place for the data that the NSA gets from that country as it is processed. An example of this can be found with the Dutch spy agency called AIVD, which can be read about more at http://basicsofdigitalprivacy.com/go/aivd, where, according to the article, which references a Dutch newspaper article, AIVD agents have access to data that have been captured and analyzed by PRISM within just 5 minutes or less of a request for the information.

The way the PRISM system works in some cases is that the system doesn’t actually track information as it travels across the Internet backbone. Instead, the NSA demands that companies such as Google, Microsoft, and Verizon hand over the data that they need on a regular basis so that they can go through this information. One of the key reasons that the NSA likes gathering the data from these large companies is that even if the network traffic between servers is encrypted when that data is stored, it will be stored with headers in plain text so that the NSA can just read the headers. Even if the data were stored by these companies using some sort of data encryption, because these companies have the encryption keys, they are able to simply decrypt the data when handing it off to the NSA.

Why then would companies outside of the United States want to get into bed with the NSA? There are a few possibilities:

1. The NSA is able to convince these companies that they have to follow US law because they may or may not be doing business with people within the United States.

2. The NSA is able to get the government of the other country to force the companies within their country to do what the NSA wants.

3. The NSA uses operatives from either the NSA or the CIA to force the companies to do what they want, probably without the company's knowledge.

No matter how it happens, the fact is that it is happening, and if you talk to people in other countries, those data are being captured somewhere and handed off to the NSA in some way.

Canadian version of PRISM

According to the Toronto Globe and Mail, the United States isn’t the only county where its citizens need to worry about the government tracking everyone that you talk to. In Canada, there is a program that sadly doesn’t have a name as great as the US NSA program called PRISM (at least as far as we know as of the writing of this book in summer of 2013). This program, which you can read more about at http://basicsofdigitalprivacy.com/go/Canada, works in much the same way as the US program capturing what the mass media and press calls the metadata about the conversation. These metadata include things like who is talking to who online, when the conversation happened, and for how long, without tracking the actual conversation. When dealing with phone calls, the same sort of metadata are captured with the data being captured being the phone number who made the call, the phone number that was called, the date and time of the call, and the duration. It isn’t a stretch to assume that GPS location is also included if the call is made to a cell phone as that information would be available to the cell phone company.

This program that is run by the Communications Security Establishment Canada was first approved by the elected government in 2005 by then Defense Minister Bill Graham. According to the Globe and Mail article, which you can read in full at http://basicsofdigitalprivacy.com/go/globe, this program was shut down for a period of time starting in 2008 and was restarted in 2011 when then Defense Minister Peter MacKay signed a new order allowing the program to be restarted and starting other classified espionage programs.

Is all this legal?

When it comes to monitoring programs like PRISM and the Canadian version that we don’t know the name of or versions of this program run in other countries, a big question tends to be, how are these programs legal?

Well the frank answer is that they might not be, but that’ll depend on who you ask and how you ask the question.

Focusing on the United States for a minute, as that’s where I live so those are the laws that I know the best, the law is murky on this at best. Here in the United States, we have the constitutional right against self-incrimination. However, the courts have ruled recently that communications that are heard by a third person aren’t private, and if that third person wants to tell the government about the conversation, they are allowed to. Along with that, the courts have ruled that the fact that a conversation itself between two people while being privileged, the fact that the conversation happened isn’t privileged. This is how the NSA program that may catch communications of people within the United States gets through. All they are capturing is the fact that it happened and who it was with.

Let’s compare an online situation with an off-line situation. In the off-line world, if two people are sitting in a park having a conversation, a government employee, most likely a city police officer, can make note of the people sitting next to each other talking without any legal issues. However, if he pulls out a long range microphone to listen in, odds are, he’ll need a warrant. In the online world of voice over IP (VoIP) communications, the same rules apply. The government is able to get the status of the call from the VoIP provider without issue, but if they want the contents of the VoIP call, they will need a warrant before the VoIP provider is required to record the call for them.

At some point, I would imagine that the courts will rule on the issue of needing a warrant just to get the metadata of the call, but as of the summer of 2013, the issue hasn’t been brought before any court that has been able to strike it down.

Is all this moral?

The answer to this one is a lot easier than the “is this legal” question. The answer here, in my mind, is no, but please don’t take my word for it. Every person has to make this decision for themselves, and there really is no right or wrong answer here. A government that tracks the technology usage of everyone on the planet is really not at all moral. Could a system like this do what it’s supposed to do, which is to stop a terrorist attack? The answer there is possibly. But is it worth the invasion of people's privacy that it takes to gather data at this level? The answer there is a personal answer, but my answer is no.

Summary

As of the writing of this book in the summer of 2013, we don’t know much about these data collection systems. We have to make a lot of assumptions about them and how we should be protecting ourselves from gathering up data that we don’t want the government knowing about. There is a theory that if you have nothing to hide, you shouldn’t mind the government knowing what you are doing. However, your information is yours and you shouldn’t be forced to hand over the information without having the option to keep it to yourself. With much on this information, it is easy to control who gains access to it. If we don’t give up the information to a company, then we don’t have to worry about a government gaining access to that information. We make this decision by simply not using some services that are out there. When we use some of these services, we need to understand that information is being collected by these companies that we are using and that these companies can be handing this information over to government agencies.

With encryption systems like we learned about in Chapter 6, we can do our best to prevent the government from viewing or tracking what we are doing online. However, this only works when these monitoring systems are capturing data during transmission, not when they are capturing data at the source or destination servers.

The worst part about these systems is that the information about them is often highly classified, which means that we won’t get to know anything about these systems until long after changes to the systems.