188 THE GAME PRODUCTION HANDBOOK, 2/E

about one month before beta. If it is in the contract, the final music deliverable

should also include the stems. Stems are the individual instrument tracks that

exist within the final music mix. The stems can be used to compose variations for

commercials, game trailers, or future games.

Plan to have all the music rights finalized and contracts signed about one

month before beta. This ensures that everything is ready to go in time for the

game’s ship date. If you can’t get a music track secured by beta, think about re-

placing or removing that track from the game.

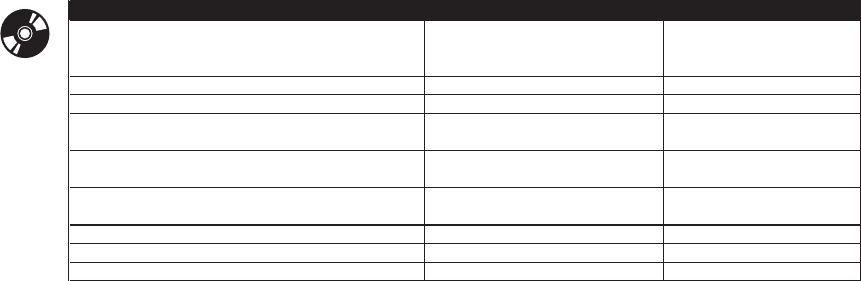

Figure 11.1 is a general overview of the music deliverable schedule for a

game. When the composer starts delivering music for you to listen to, you will

want to schedule the specific deadlines for sending him feedback and getting the

revised music tracks back for review.

Bid Packages

Send bid packages to several composers during pre-production so you can get

an idea of prices, how responsive they are, their music style, and how long it will

take them to compose music for your game. Composers might have a preferred

format for receiving bids, so check with them first for any necessary forms. In

general, the bid packages must include as much information about the game’s

music needs as possible. Things to include are as follows:

■

Grand total for many minutes of music are needed

■

How many different pieces of music are needed

■

How long each piece of music must be

■

Specifics on where each piece of music will be located in the game (UI, in-

game, cinematics)

■

Any sound, voiceover, and music mixes that are needed

■

Format for music deliverables

■

Final deadline for receiving all final deliverables

O

N

T

H

E

C

D

FIGURE 11.1 General overview of music deliverable schedule.

enildaeDecruoseRksaT

st

r

ats

n

oitcud

o

rp erof

e

Bre

e

nignE dnu

o

S/re

n

giseD dnuoSde

ni

mreted ngised cisuM

Initial music deliverables defined Sound Designer By Alpha

Add placeholder music in the game Sound Designer By Alpha

Send bid packages to composers (if working with

ahp

lA yBrecudor

P)r

e

s

o

pmo

c lanret

x

e

a

h

plA

yBr

e

c

u

d

orP)

c

is

um

g

ni

s

n

eci

l

fi(

s

thgir cis

u

m r

of

gnit

aitog

en

t

r

at

S

ateB erofe

b

sh

tn

om 3 -

2 ~

r

esopmoCresopmo

c

eht

yb dereviled

s

n

oi

tisopmoc

f

o

tes

t

sriF

a

teB erofeb htn

o

m 1 ~res

o

p

m

oCsexim

cis

u

m

lanif srevi

l

e

d

r

e

sopmoC

ateB erofeb htnom 1 ~recudorP sthgir cisum lani

f

l

l

a

eruceS

Implement all final music in the game Sound Designer By Beta

MUSIC 189

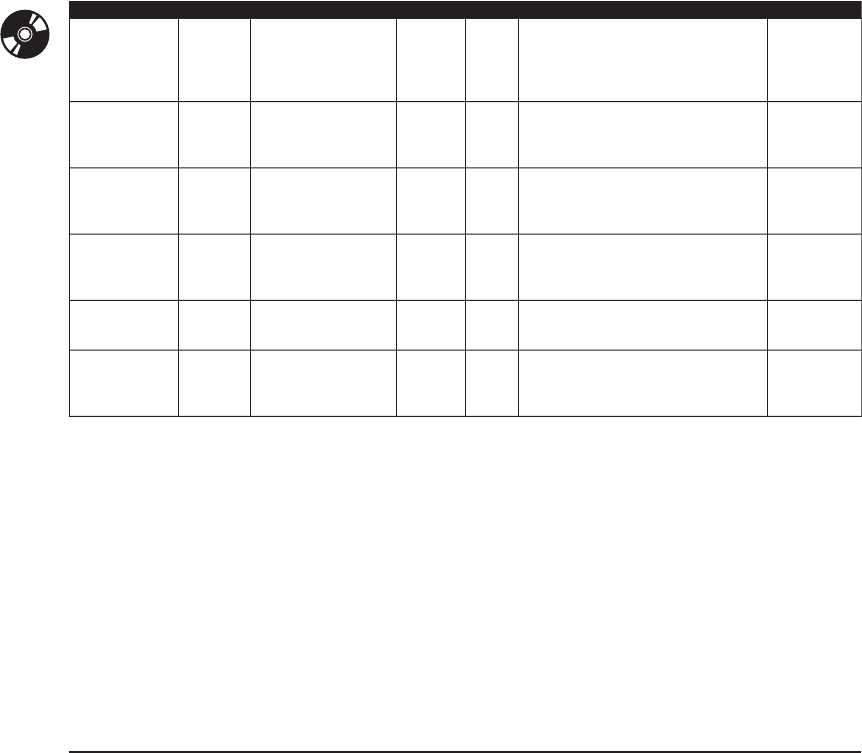

Figure 11.2 is an example of what information you should include in a bid

package. This is a fairly straightforward way of organizing what music cues are

needed and the deadlines.

In addition, you will need to provide some documentation and samples on

what you want the music to sound like. The music vision document should pro-

vide general information on the music genre, gameplay themes, and any other

special considerations (such as regional flavor). It should also include samples of

music from other games, soundtracks, bands, composers, or any other audio that

can closely convey the look and feel you want for the game. After you send out

the bids, follow up with each composer and make your final selection.

11.3 WORKING WITH A COMPOSER

Most likely, your sound designer will be working directly with the composer.

The producer is usually involved as a sounding board for opinions and might

have final approval on the final music tracks for the game. The producer is defi-

nitely required to approve the deliverables and make payment to the vendor.

Before the composer can begin working on the music, he will need to get a

much better idea of what the game is about. So send him a build of the game or

a game trailer if a build is not available to play. In addition, concept art, character

O

N

T

H

E

C

D

FIGURE 11.2 Music bid example.

Music Cue Length Mixing Details Location Format Notes Deadline

Main Theme 120 secs Full Dolby 5.1 mix UI .wav

Main theme for the game, will be heard

whenever players are in the UI shell

screens. Must match the look and feel

outlined in enclosed "Music Vision"

7

0

0

2

,

0

3 lirpA.t

n

emuc

o

d

Loop 1 30 secs Stereo In-game .wav

Heard in game as a looping piece of

background music. Must match the look

and feel outlined in enclosed "Music

7002 ,03

yaM.tnemuc

o

d "noisiV

Loop 2 30 secs Stereo In-game .wav

Heard in game as a looping piece of

background music. Must match the look

and feel outlined in enclosed "Music

7002 ,03 yaM.tnemucod "noisiV

Intro Cinematic 180 secs

Stereo, music +

voiceover + sound

effects, music must be

timed to picture. Cinematic .wav

Deliver final music, vo, and sound effects

mixes on separate tracks. June 30, 2007

Midtro Cinematic 60 secs

Stereo, music only,

background music, no

timing. Cinematic .wav

Deliver final music, vo, and sound effects

mixes on separate tracks. June 30, 2007

Outro Cinematic 90 secs

Stereo, music +

voiceover + sound

effects, music must be

timed to picture. Cinematic .wav

Deliver final music, vo, and sound effects

mixes on separate tracks. June 30, 2007

190 THE GAME PRODUCTION HANDBOOK, 2/E

descriptions, and the storyline can also be helpful to convey the look and feel

of the game. The composer can review these elements, along with the music

vision document, to determine the themes and inspiration for the music.

After the composer has these elements, he can begin roughing out the music

tracks. Plan on several rounds of feedback between the composer and sound de-

signer, before the final music is ready. The composer will provide a rough audio

mix of the initial music that can be reviewed by the sound designer to ensure that

it is on the right track. This is where the feedback process begins.

The feedback process needs to be well-defined beforehand so that time is

used wisely and the composer is not waiting weeks (or months) for feedback. It is

important that all feedback is communicated in writing to all appropriate parties.

If verbal feedback is provided via a conference call, write up the notes from the

conversation and email them to make sure there is a written record.

Establish deadlines for when feedback will be provided and when it will be

implemented. For example, when the composer delivers samples for review,

he should expect to hear feedback within three days. If no feedback is given,

he can assume that everything is fine and proceed with the next phase. After

the sound designer has given feedback, the composer needs to determine when

the next set of samples with the feedback incorporated will be ready for review.

This deadline is communicated in writing to the sound designer.

Finally, when anyone is giving feedback, make sure that it is useful and con-

structive. It’s not enough to say “eh, I really don’t like this, but I can’t put my

finger on why,” because that gives the composer nothing to work with. He won’t

know what to change in order to get it the way you want. Instead, be specific

about what you don’t like, even if you think it sounds silly. For example, “I really

don’t like the screeching at the end of the song, it is too shrill and may annoy the

player. Maybe it can be toned down or replaced with something else.” This type

of feedback is much easier to work with. If possible, provide specific time codes

on the areas of the music you are critiquing.

It is a good idea to gently remind composers of upcoming deadlines, so they

can be sure to deliver on time. They might get so caught up in doing the work

that they forget their final deadline is in three days. This way, you can be sure

that you have everything you need when you need it.

11.4 LICENSING MUSIC

If you are licensing music, determine which bands you are interested in and start

contacting their publishers. The publishers usually handle all negotiations for

music rights. If it is a popular band, these negotiations can take some time, so

start the process as soon as you can. Keep in mind that if you are licensing music,

it is likely you will not be able to alter it in any way.

MUSIC 191

The contract might limit how many minutes can be used, how much addi-

tional mixing can be done on the track, or what other bands can appear in the

game. The rights may cost a flat fee or may entail an advance against royalties on

each copy of the game sold. You might also be able to get the band to record a

special version of the song or even record an original song for use in the game.

The game publisher will likely have their legal department involved in the

process as well. This way the publisher can be sure that all the appropriate rights

are accounted for in the agreement. The agreement should clearly define how

the music can be used in the game, how the music can be used in marketing

materials, and whether the music can be used on demos or game trailers. It

should also detail whether the track can appear on a game soundtrack, which is

something that is becoming more common.

WORKING WITH A COMPOSER

Raymond Herrera

3volution Productions

I have been playing games since I was 10-years-old and have always wanted

to blend music and games together. I started 3volution Productions along with my

business partner, Laddie Ervin, to make this happen. We are involved in all as-

pects of audio and games: composing original music, licensing music, voiceover, and

sound effects. Our gaming background makes it easier for us to work with develop-

ers in determining the music needs for the game. In some instances, the developer

will know exactly what is required—15 songs for X amount of money. Other times,

the developer is looking for some guidance on what music to include in the game—

original music, licensed music, and so on.

The biggest factor in determining the music options for a game is how much

money is available and how much music is wanted. If a lot of music is needed and

the budget is limited, the developer can remix songs. Remixed songs are beneficial

to the game and the band. The band now owns a remix and has worked with people

they never thought they would work with, and the game gets a custom track and the

ability to use the band’s name, without a high sticker price. When doing remixes, ac-

tual sounds and voiceovers from the game can be used to really tie it into the game.

For example, 3volution used the team call-outs and the ammo sounds the player

hears in the game for the Rainbow Six: Lock Down theme.

I believe that videogames can benefit from using music the same way that mov-

ies currently do—select a hit song that can be used as an anchor and then remix it

or license the original and feature it in the marketing campaign. This song can then

192 THE GAME PRODUCTION HANDBOOK, 2/E

be the feature on a game soundtrack, along with other music that is inspired by the

game.

Another way to get quality music without spending a ton of money is by putting

together a super group of musicians who work for a few days on creating and record-

ing a song that exists only for the game. For example, for the WWE game 3volution

worked on, there was a super group that consisted of me on drums, Shavo from

System of a Down on bass, Wes from Limp Bizkit on guitar, B-Real from Cypress

Hill on vocals, and DJ Lethal as the DJ. In some cases, marketing will pay to have a

music video made for this song and played on MTV.

In order for us to make the most impact with music, we like to be involved

with the game at the pre-production phase. This way, we can find creative ways

for developers to make the most of their budgets. For example, if we put together

a super group to record a song, marketing can be persuaded to have the money for

this come out of their budget. This means the developers don’t have to invest a lot

of money in the music, but still get a unique and high-quality song for their game.

Also, if we are involved early on, we can make sure the music, voiceover, and sound

effects are tightly integrated.

When first starting to work on a game, talk with the developers to find out

what they need and what the attitude of the game is. Then talk to the marketing

people. When talking with the marketing people, get them excited about all the

cross-promotion opportunities—game sound tracks, iTunes, bands going on tour

and showing clips from the game, and music videos.

The process begins with a conference call between 3volution and all interested

parties. When the initial meetings are completed, we create a guideline based on

these discussions of what type of music will be created, the file formats, and any other

notable details of the deliverable. This is sent to each and every person involved in

the process—the publisher, the developer, marketing, and so on. This guide is use-

ful because it holds everyone accountable to what was said and agreed upon. After

that, all feedback is handled via email. Everyone is copied on the email chain so

everyone has a chance to give their opinion. In addition, milestone deadlines are set

up and scheduled with the developer. More time means better quality.

Music is the last thing that is worked on in the games. We are hoping this will

change because music can be integral part of making a game more effective and fun

to play.

11.5 CHAPTER SUMMARY

Using music effectively in games is not difficult to do. If you are able to de-

fine your music needs up front, you can determine whether you need to hire

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.