GAME PLAN 281

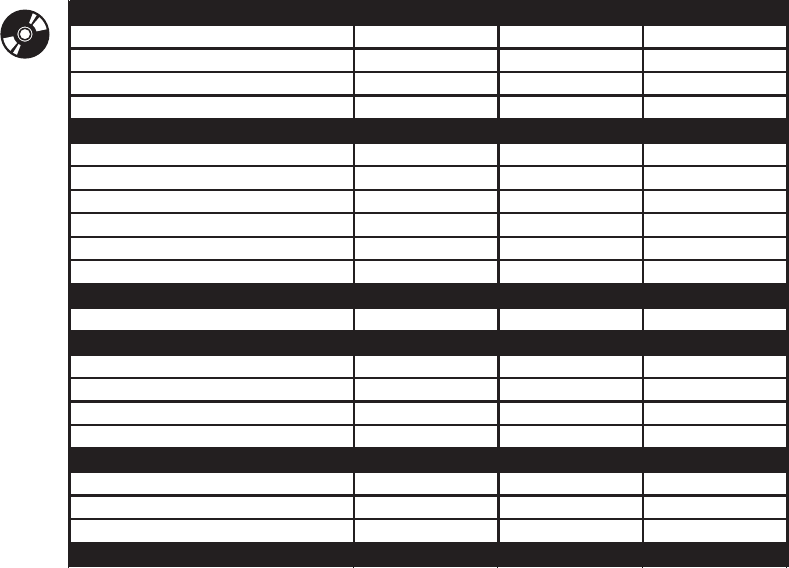

Figure 16.12 is a sample budget for the other costs on a project. In this ex-

ample, the “Number” column is used to indicate multiple purchases of a given

item—for example, 10 computers. The “Number” column is multiplied by the

“Rate” column to determine the total “cost” for each line items. These, in turn,

are added for the grand total.

After the development budget is determined, it can be added to the pub-

lisher’s P&L statement to determine whether the title will yield a profit. If not,

you will be asked to make adjustments to the budget and schedule until they are

satisfactory.

Managing a Budget

As with the schedule, you will need to track your budget during the development

process. The same person who is appointed as the schedule tracker is also a good

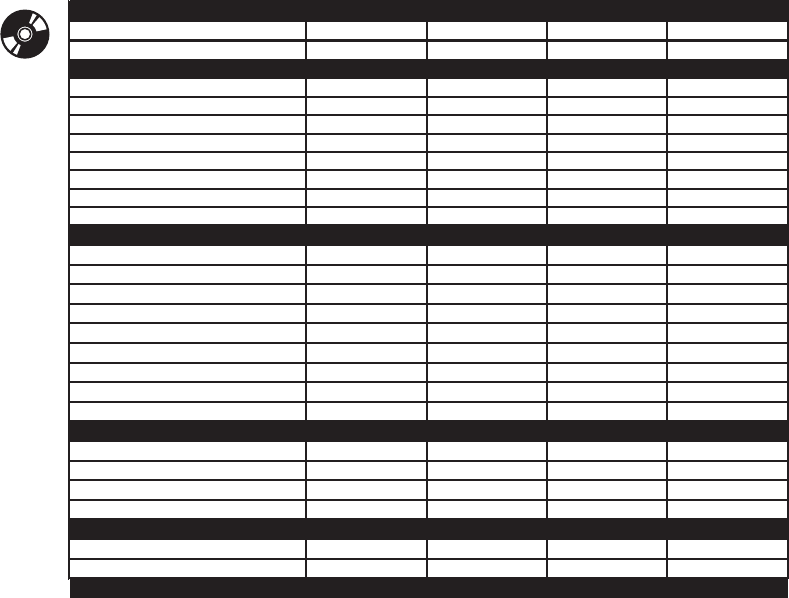

Production Personnel Number Monthly Rate # of Months Cost

Producer 1 $8,000 24 $192,000

Associate Producer 3 $6,000 18 $324,000

Art Personnel

Lead Artist 1 $10,000 24 $240,000

Technical Artist 1 $8,000 24 $192,000

Concept Artist 2 $6,000 10 $120,000

World Builder 10 $6,000 12 $720,000

Object Artist 3 $6,000 8 $144,000

Texture Artist 4 $6,000 12 $288,000

Marketing Artist 1 $6,000 12 $72,000

Animator 3 $8,000 8 $192,000

Engineering Personnel

Lead Engineer 1 $10,000 24 $240,000

Networking Engineer 2 $8,000 16 $256,000

Graphics Engineer 4 $8,000 18 $576,000

UI Engineer 1 $8,000 12 $96,000

AI Engineer 4 $8,000 18 $576,000

Sound Engineer 1 $8,000 12 $96,000

Tools Engineer 3 $8,000 18 $432,000

General Engineer 5 $8,000 18 $720,000

AI Engineer 2 $8,000 12 $192,000

Design Personnel

Lead Designer 1 $8,000 24 $192,000

Designer 4 $6,000 18 $432,000

Sound Designer 1 $6,000 12 $72,000

Writer 1 $6,000 6 $36,000

QA Personnel

Lead QA Analyst 1 $8,000 24 $192,000

Tester 20 $6,000 10 $1,200,000

GRAND TOTAL 80 $7,792,000

Based on 24-month development cycle

Monthly rates are for example only, do not reflect actual rates

FIGURE 16.11 Sample budget for personnel costs on a project.

O

N

T

H

E

C

D

282 THE GAME PRODUCTION HANDBOOK, 2/E

candidate to be the budget tracker. Any budget expenditures should be noted on

a weekly, or at least a monthly, basis.

The studio or publisher’s accounting department will also be involved in

watching the budget. They keep records of all the expenditures on the game—

salaries, hardware purchases, and costs of external vendors—and will allocate all

of these things against your game’s budget. They are a good source of information

if you need to find out the total amount spent on the game at any given point.

Keep detailed records for any expenditures. Each studio has a different pro-

cess for paying expenses, so check with the accounting department and studio

management on what forms need to be filled out to make purchases, pay a ven-

dor, or hire new team members. For example, if paying an external vendor, you

might need to get an invoice and detailed statement of work from the vendor.

Hardware Number Rate Cost

Computers 80 $3,000 $240,000

Console Development Kits 40 $10,000 $400,000

Controllers 60 $100 $6,000

Graphics Cards 80 $300 $24,000

Software

Perforce 76 $750 $57,000

3DSMax 19 $4,000 $76,000

Photoshop 4 $600 $2,400

MS Project 5 $1,000 $5,000

Unreal 3.0 Engine 1 $1,000,000 $1,000,000

Visual C++ 23 $3,000 $69,000

Licensing Fees

Justice Unit Royalty

1 $500,000 $500,000

External Vendors

Voiceover 1 $250,000 $250,000

Music 1 $50,000 $50,000

Cinematics 1 $300,000 $300,000

Localization 4 $50,000 $200,000

Other

Travel 24 $1,000 $24,000

Food 24 $500 $12,000

Shipping/Postage 24 $200 $4,800

GRAND TOTAL $3,220,200

Based on 24-month development cycle

Rates are for example only, do not reflect actual rates

FIGURE 16.12 Sample budget for other costs.

O

N

T

H

E

C

D

GAME PLAN 283

After receiving this, you might need to fill out a check request form and submit

it to accounting for payment. The form probably will ask for general information

about the expenditure: was it budgeted and what part of the budget is it applied

to. After all the paperwork is received, accounting will cut a check and mail it to

the vendor.

If you find that the project is going over budget, don’t ignore the problem

because it won’t go away. Instead, take time to re-asses your game plan and de-

termine whether there are any adjustments that can be made to the schedule,

staffing, or scope of the project.

16.5 STAFFING

The schedule details what work needs to be done, and the staffing plan deter-

mines who will do it. When these elements are combined, and the resources are

added to the schedule, it determines when all the work is completed. Therefore,

it is important to understand the strong dependencies between the staffing plan

and schedule. The staffing plan is also affected by budget; if you need to hire

additional people to complete the work, you need to have money in the budget

to do this. If you can’t afford extra people, you will need to reduce the scope of

work so that the people you do have available can complete it on time and at

budget.

Your staffing plan is largely based on what tasks must be completed. For

example, if the game requires 10 character models and five levels, you are going

to need several artists to complete this work. If the game is utilizing brand new

technology, you’ll want to have enough engineers on the project to prototype,

code, and debug it. In the sample schedule illustrated in Figure 16.7, the sched-

ule can be brought in a few days if more artists and designers are added to the

project. As you can see, it is helpful to add or subtract people to the schedule

to determine the effect this has on the deadlines. After you find a good balance

between the tasks to be completed and people needed, you can fully define your

staffing plan.

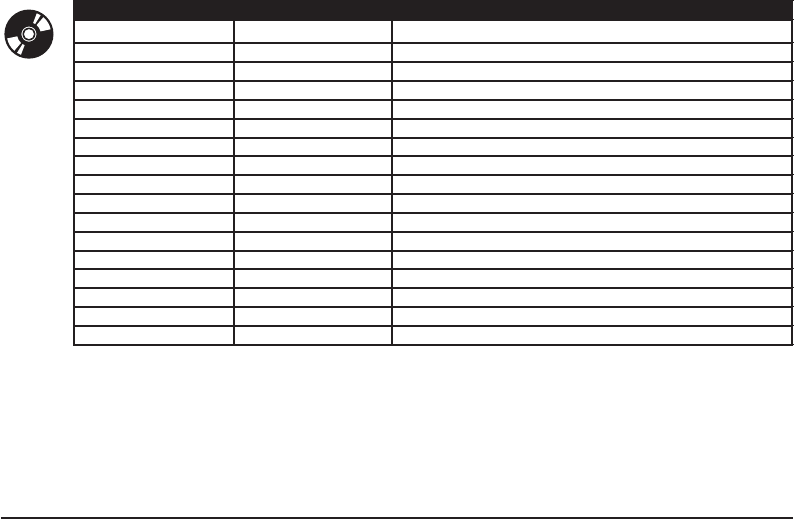

In general, the pre-production phase will include a small group of people

that will be on the project until the end. During production, people will roll

on and off the project as needed. By beta, the team will again be reduced to a

small group of people who will bug-fix and code release the game. All of these

staff changes will be reflected in your production schedule. Figure 16.13 is an

example of partial staffing list for a game with a two-year development cycle.

The information was pulled from the schedule and contains an overview on the

amount of time people are needed for the project.

284 THE GAME PRODUCTION HANDBOOK, 2/E

16.6 OUTSOURCING

Outsourcing work to an external vendor is a good way to save time and possibly

money on the project. You might want to use an animation house to create the

game’s introductory movie so that your artists can focus on creating in-game

content. Obviously, using an external vendor saves time for the internal develop-

ment team since they are not responsible for completing a given section of work.

Money is saved if the vendor can do something more quickly and/or cheaper

than the internal development team, such as voiceover recordings.

There are many types of game development services you can outsource with-

out impacting the quality or schedule of the project. These areas involve design

and art assets, as these tend to be discreet sets of tasks that are not dependent

on work from several parts of the team. Other things to outsource include the

following:

■

Cinematics and animation

■

Motion capture

■

Voiceover

■

Music

■

Sound effects

■

Writing

■

Localization

Role Duration Notes

Lead Artist 24 months Need for pre-production, production, code release.

Concept Artist 10 months Need for pre-production and part of production.

World Builder 1 12 months Need for production.

World Builder 2 12 months Need for production.

World Builder 3 12 months Need for production.

Texture Artist 1 8 months Begin after first round of levels are geometry complete.

Texture Artist 2 8 months Begin after first round of levels are geometry complete.

Lead Designer 24 months Need for pre-production, production, code release

Designer 1 18 months Need for production.

Scripter 1 8 months Will start after first round of levels are built and textured.

Scripter 2 8 months Will start after first round of levels are built and textured.

Producer 24 months Need for pre-production, production, code release.

Lead Enginer 24 months Need for pre-production, production, code release.

Engineer - Multiplayer 16 months Need to start right after pre-production.

Engineer - Tools 18 months Need to start right after pre-production.

Lead QA Analyst 24 months Need for pre-production, production, code release.

Tester 1 10 months Part-time for alpha, full-time at code freeze.

Based on 24-month Development Cycle

FIGURE 16.13 Example of partial staffing list.

O

N

T

H

E

C

D

GAME PLAN 285

Outsourcing engineering tasks is not recommended, as the engineering tasks

are more dependent on each other, and code merges can be time-consuming,

making it difficult to test outsourced code on a regular basis. Additionally, an

engineering vendor will need access to source code, which is highly confidential,

and will need to set up a development environment that exactly matches what

the internal engineering team is using.

Before contacting an external vendor, clearly define the scope of work to

be outsourced. The earlier worked can be scoped out, the more prepared the

vendor is to accurately estimate the workload and complete it on time. Also,

provide as much information as needed to the vendor about the game, as this

will help them plan their work better. For example, if hiring an external vendor

to compose music for the game, it is helpful to show them concept art, playable

prototypes, the style guide, and anything else that can help them get a good idea

of what the game’s vision is and what music will best fit with this vision.

As with any project, there are pros and cons to working with external vendors.

Overall, using a vendor can save time and resources during the development pro-

cess, making it more likely for the game to be finished on time. Another benefit

is that the team can concentrate solely on their tasks for the game and spend ad-

ditional time play-balancing features, fixing bugs, and polishing the assets so the

game is the best it can be. If you select vendors that are highly specialized in one

area, their quality of work will be high and will contribute to the overall quality of

the game, leaving the team to concentrate on the areas they do best.

There are a few drawbacks to working with a vendor, such as the extra costs

involved. But if the project is large and complex, the cost of an external vendor

might be worth the time and resources saved by the internal development ef-

forts. Another drawback is that the developer loses the flexibility to shift project

deliverables and internal deadlines around. When working with a vendor, the

developer must to be organized and confident in the team’s ability to meet key

milestone dates. The developer needs to provide the vendor with necessary as-

sets when needed. For example, a cinematics vendor might need to have the

final character models to complete the final version of the movies. Providing

this information requires the developer to think months ahead in the production

cycle in order to give accurate estimates to the vendor.

Another large risk to outsourcing is the vendor might not meet his deadlines.

This can severely impact the project if the deadlines are extremely tight. In order

to mitigate this risk, be sure to schedule ample time in the schedule for finding

a vendor. Additionally, after you get the vendor’s schedule, add some padding to

it so there is some slack if needed. It is never a good idea to schedule a vendor’s

deadline at the same time as a major milestone. For example, don’t have a ven-

dor deliver final cinematics or music on the beta date; plan to have it delivered

at least a week ahead of time.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.