Chapter 5

Coaching Advisors to Grow the Business

“Without a coach, people will never reach their maximum capabilities.”

—Bob Nardelli

You Can't Coach Desire

Bill Bowerman: “Nobody can coach desire, Pre,” the track coach at the University of Oregon said to Steve Prefontaine in the 1998 movie Without Limits, a great movie about what it takes to have heart. William Jay “Bill” Bowerman was an American track and field coach and co‐founder of Nike, Inc. Over his career, he trained 31 Olympic athletes, 51 All‐Americans, 12 American record‐holders, 22 NCAA champions and 16 sub‐four‐minute milers. Leaders with a growth mindset invest in the growth of others. It's the best way to have an impact and leave a legacy. In the long run, no one will remember if you recruited three top producers or you grew your revenues by 30 percent. But people with whom you had a meaningful impact will remember you forever. That is how great leaders create more great leaders. They do this both informally, by setting an example that others want to emulate, and formally, by consciously and conscientiously investing time in developing the talents of the people they work with. But they understand that you can't coach desire. It's the biggest mistake I made as a manager in terms of coaching: trying to motivate the unmotivated. It's not the one who outright lets you know that he or she has no interest in growing or coaching or receiving help from you or anyone else. This advisor is being honest with the manager and him‐ or herself. It's the advisor who placates you and tells you what you want to hear who will have you spinning your wheels. That's the one who will drain your energy because it's in your nature to help people, to make a difference. It doesn't take much to get hooked into believing that these people are committed because that's what we want to believe. Therefore, before you focus on coaching be sure your advisors or managers are not only open to but committed to improving.

What Do You Want to Talk About Today?

“Most people, even though they don't know it, are asleep.”

—Anthony DeMello, Awareness

Many people are unaware of their potential, or most certainly the depth of their potential, until someone points it out to them. Even if they are aware of it, they may not be able to reach it without a helping hand from someone with more experience and know‐how. That's where coaching comes in. Many live in an insular world and measure results based on poor information. For example, when someone says, “I'm doing well,” I like to ask relative to what. Are you measuring against firm skills and objectives; are you setting your own standards? As Mark Sutton (former president of UBS) used to say, “Anyone can seem like they are running fast next to an oak tree.”

A Parable: The Eagle Who Died a Chicken

Earn the Right to Coach

In the right environment and with the right coaching, we all have the potential to reach new heights. Great leaders know this, but too many on‐the‐ground managers do not. When I ask managers how many coaches they had when they were an advisor, only about 20 percent say they had coaches who made a difference in their career development. That's true for me as well. This fact is unfortunate, but perhaps not surprising. When you think about it, how much training have you had that provided you with the tools necessary to make a difference in someone else's behavior? Many people believe coaching is important, but far too many don't take the time to master the skill.

I Don't Coach Because:

- I'm too busy—47 percent

- My advisors are not receptive—24 percent

- I'm not sure how to do it—15 percent

- There's no incentive associated with the action—11 percent

Source: Spectrum Group

I encourage you as part of your own leadership and professional development to learn how to coach effectively. Like everything else it takes time and a lot of practice to become effective. The highest compliment someone can pay you is asking for your help, to be coached by someone she respects and who has achieved success. And you yourself cannot be an effective coach if you are not coached from time to time—no matter what stage of your career you are in.

When we talk about relationships, we have to understand feelings and be able to identify our own feelings and those of the people we're working with—whether it's through coaching or just plain trying to understand a team member or client. First, identify the feelings of the person with whom you are interacting so that you can determine whether he is in a negative or positive state. If the person is coming from a negative place, you can help him take action toward a more positive state. Identifying the right feelings and choosing the right words could help you have a more effective coaching conversation. The following pairs of feelings may be useful for learning how to identify different types of emotions:

| Turn the negative . . . | . . . into the positive |

| Suspicion | Trust |

| Fear | Hope |

| Sadness | Joy |

| Weakness | Strength |

| Unfulfilled | Satisfaction |

| Rejection | Support |

| Confusion | Clarity |

| Shyness | Curiosity |

| Boredom | Involvement |

| Frustration | Contentment |

| Inferiority | Superiority |

| Repulsion | Attraction |

| Hurt | Relief |

| Loneliness | Community |

| Hate | Love |

| Anger | Affection |

| Scarcity | Abundance |

| Unimaginative | Creative |

| Insensitivity | Compassion |

| Insecurity | Confidence |

“The day soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you have stopped leading them.”

—Colin Powell

As I said earlier, I encourage you to carefully consider whom you choose to coach. Your time is precious. Focus on people who will appreciate what you have to offer and will do something with the guidance you provide. If you can't measure the progress it's difficult to make adjustments and as a result the conversation becomes just emotional.

One of the coaches I have worked with over the years as a professional is Dr. Tim Ursiny, the CEO of Advantage Coaching & Training. Tim has taught thousands of leaders coaching skills and truly understands what makes a successful coach. Tim emphasizes the importance of a coach having two sides: the soft side and the hard side. The soft side includes things like being a good listener, being inspirational, building trust quickly, asking powerful questions, and truly believing in the coachee. The hard side is the ability to challenge someone, hold him accountable, set objectives, and stretch him to his potential. The soft side alone is inadequate because it creates comfort and potential complacency. The hard side alone does not create the safety that the coachee needs to be vulnerable, admit mistakes, and show humility. Most coaches tend to be weighted more heavily on either the soft or the hard side, but the best coaches develop both sides and with it the ability to be creative and drive performance. They build a positive rather than a punitive accountability in which the coachee is recognized for her performance and challenged to perform at her highest level.

Great coaches must also differentiate from pure Socratic Method–based coaching versus mentoring. Both pure coaching and mentoring are valuable, but they offer different ways of interacting with the coachee. They can be combined for a powerful impact, but this only works if the coach knows the difference between the two styles and is able to apply whichever is needed for the situation at hand. With mentoring, the mentor is the expert. To be a mentor you often have to have a track record of coaching success or at least be able to prove your expertise on the topic. People often want mentors instead of Socratic Method–based coaches because they want to hear your advice; they want to know how you did what you did. In Socratic Method–based coaching your expertise is not necessarily part of the discussion, it's more about your ability to pull out your coachee's expertise, wisdom, and creativity and focus them on action and accountability. Thus, a coach who has never worked as a financial advisor can still coach a financial advisor.

According to Tim, the challenge is that many, if not most, managers tend to “tell” too much rather than ask powerful questions that get the coachee to self‐discover the answers. If you have the discipline and the skill to get your coachees to determine answers for themselves, then you get more ownership, buy‐in, and accountability from your coachees throughout the process. If they tell you what they need to do, how they need to do it, and by when they will get it done, they are much more likely to go after that outcome with ownership and passion.

It may sound easy to use questions to help people self‐discover, but Tim frequently points out that the problem with that method is conditioning. In most educational experiences, we are rewarded for coming up with an answer and solving a problem. We are not rewarded as frequently for our ability to ask really good questions. When coaching, many managers feel (due to good intentions and conditioning) the strong urge to provide the answer for the coachee. While this can be helpful at times, there are other times where this approach will be harmful to the coaching process and create resistance from the coachee. Therefore, the best coaches must have the ability, through practice, to go beyond their conditioning and approach their coaching with complete awareness of when they are asking versus when they are telling.

Alternatively, when a coachee is willing, ready to act, and it is not necessary for him to become a better thinker/problem‐solver on a certain topic, then it is fine to mentor. When the coachee is resistant, puts up blocks, or is unwilling or unable to figure out his solutions and actions himself, then you will want to employ more questions and reflections to get to the desired outcomes.

On the topic of resistance, Tim and I have discussed the fact that many advisors are not willing to be coached and he has shared a few insights on this issue. The first is that higher‐performing advisors are actually statistically more willing to be coached than lower‐performing advisors. He hypothesizes that this is due to higher‐end advisors being more driven and constantly wanting to outperform others or even their own past performance.

His other insight is that, in his experience, most advisors are actually more willing to be coached than it first appears. In fact, he would go so far as to say that out of 10 people who appear unwilling to be coached, only one is truly unwilling. The key is in how you frame the coaching. The initial engagement must tap into the potential coachee's motivators, not what motivates the coach or the firm. Hard‐driving, confident, fast‐paced advisors tend to be motivated by results and growth. When they believe that coaching will get them better results, and, if they respect the coach, they will be much more likely to engage in coaching.

Advisors who are kind, patient, more reflective individuals may be less motivated by results or less focused on image focus, but they can be highly coachable when they see how working with a coach will create more stability and security in their lives. Individuals who are more analytical, systems‐oriented, and logical are more open to coaching when they see the logic behind it, when it is presented as a clear process, and when it increases efficiencies.

It is important for a coach to uncover the personality and motivations of the coachee in the initial discovery session in order to frame the coaching appropriately. When this is done well, the number of people willing to be coached increases dramatically.

Whether the coachee is focused on results/growth, image/impact, stability/security, systems/efficiencies, or any combination of these, the key is to help the coachee achieve the outcomes she wants. Tim has told me that one of his most valuable questions in his discovery meeting is, “What does success look like?” He wants the coachee to paint a vivid picture for him of the intended outcomes from the engagement. Subsequent coaching is all done with this outcome in mind and every action step generated through the coaching should be relevant to that vision. He also likes to ask, “What will achieving that do for you?” This question helps coaches get to the root motivators. Tim also shares that if the coachee does not show some level of energy or passion when answering that question then she is likely not motivated enough to put in the hard work to go after that goal.

People often ask about when to use an inside coach (the manager) versus when to use an outside coach. Tim offered the following:

Use an inside coach when:

- It is essential for you, as the coach, to have a complete understanding of all the internal moving parts and culture (i.e., you are concerned that your lack of knowledge could lead to poor action steps for the coachee).

- The coachee respects and trusts you and feels safe enough to be honest and open.

- You want to build your reputation within your firm for your coaching skills and have the ability to get great outcomes.

Use an outside coach when:

- You have not sufficiently mastered both the soft and hard sides of being a great coach.

- The coachee will be more open and honest if the person is on the outside.

- You are too close to the individual and he may benefit more from an unbiased perspective.

The bottom line is that you should use whichever type of coach will help the coachee get the fastest and most powerful outcomes.

One of the best ways you can demonstrate value is to be the most effective coach in your market. Having a reputation that you can actually help someone grow is a big deal, because most don't have this skill set. If you're committed to making a difference in people's lives, become an outstanding coach. But like so many things in our business, one never truly masters coaching. Rather, you continuously aim to be a little more effective each time.

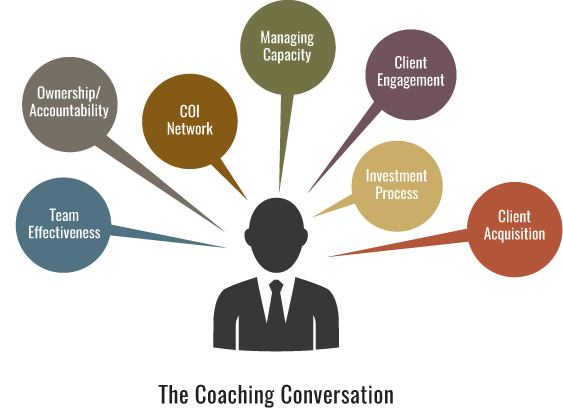

A 9‐Step Process to Achieve Coaching Success

Before engaging in the following coaching process, it's critical to set up a discovery meeting between you and the advisor. It's an opportunity to get to know one another and understand what you're hoping to achieve through the process. It also helps determine whether you can provide the right value to the particular advisor. This meeting should not be a review of the advisor's pipeline; that can be part of the discussion, but the main focus should help determine whether the coach and advisor are best matched to engage in a coaching relationship. This process is a nonstarter if neither party is motivated by the engagement. Additionally, if the advisor says he knows it all when it comes to his business, the engagement is over before it has even begun. The advisor with a growth mindset is always looking for ways to improve, right up to his last breath.

Step 1 in the process is to start with a belief audit to get a clear understanding of the advisor's worldview and beliefs. First, does she believe in coaching? How does she feel about teams? Understanding potential blocks to the process sets the stage. I can't begin to tell you how much time I have wasted trying to change people. It's exhausting. People change when they have a clear purpose and are motivated to change. You are not a magician. And generally people are most open to changing behavior when they are feeling pain.

Step 2 focuses on time management. Ask the advisor the following questions: How do you spend your time? How do you define high payoff activities? How do you manage an increase in capacity? How do you leverage resources? With technology brain hacking you at every turn, you need to help the advisor stay focused on what really matters. Help him identify all the noise in his life. There are 525,600 minutes in a year: help the advisor align his intentions with his actions.

Step 3 involves conducting a gap analysis. Hone in on helping the advisor answer the following questions: What are your strengths? What are the gaps that impede you from delivering on your promises? We all have blind spots, by the way. Help him identify his gaps. During this step you also want to analyze his level of emotional intelligence and self‐awareness. Determine what area of his work would be best served by developing new skills. Is it capital markets they need help with, planning, team collaboration? And so on.

Step 4 establishes an individual's value proposition. Ask: Who are you? Why do you do what you do? What makes you different from others in the business? Whom do you do business with? Help him become very clear on the idea that the advisor is the solution and clients ultimately buy him versus a product or service. Help the advisor discover, articulate, and deliver a confident value proposition.

Step 5 involves business development. What are the best asset‐gathering opportunities for the advisor? What are her talents and passions? There is little point in trying to convince someone to engage in an activity in which she doesn't have either the skill set or right mindset. For example, if you choose a form of exercise that you actually enjoy, you're much more likely to stick with it. But if you don't enjoy the activity, your enthusiasm will likely fade very quickly. Be mindful of helping advisors develop the right talents.

Step 6 focuses on establishing a clear set of service tiers. Basically, this step involves creating three service models in order to create unparalleled service for each client. Help the advisor identify his client segments and assess the level of service he is providing to each client segment. Help him tighten up his service model.

Step 7 analyzes the client meetings, including discovery, quarterly reviews, client events, and so forth. How effective and efficient are these meetings? How is the closing process? Who participates in these meetings? How does the advisor determine effectiveness when it comes to her own communication? Where does she get feedback on her communication style?

Step 8 focuses on client feedback. Help the advisor create the proper action plan to engage in a systematic process of receiving feedback from clients. Help the advisor decide if a client board of advisors would be appropriate.

Step 9 includes work/life balance. As the coach and/or manager are you truly interested in the overall well‐being of the advisor? Or are you only focused on the metrics? Genuinely being concerned about the person you are coaching will make you stand out as a coach because that's not the norm. As a coach and/or manager, you may play many roles—one might be the therapist while another might be the cheerleader. Help the advisor achieve an appropriate work/life balance. An advisor who is physically fit and mentally capable is more likely to achieve the growth mindset needed to excel in his business.

Once again, you have to earn the right to coach someone. Just because you have a title doesn't translate into the right to coach. Read, practice, be coached, and ask for feedback. After 10,000 hours at any discipline we can say we know something.