Chapter 21

Investment Management

As the term wealth management has become mainstream, more firms are moving toward a model that asks clients about life goals, liabilities, work, family, and spending patterns as a way to increase value. Managing money is just one part of the much bigger picture—although certainly it's a very significant part. The term wealth management was first used in 1933 and has become popular in the last 25 years. As more and more firms have started to focus on broader relationships, planning has become core just as portfolio construction. By standard definition, wealth management means serving the high‐net‐worth market, but everyone has their own definition of what wealth management means. The four stages to wealth management are wealth accumulation, wealth planning, wealth preservation, and wealth transfer. The big pillars of these stages are the risk tolerance of the client, time horizon, the risk/reward aspect of each asset class, tax efficiency, and how each component fits with the overall plan. Wealth management and investment management are not interchangeable.

Future clients will have more options on how they invest. They will have a number of choices: do‐it‐yourself robo, robo‐assisted, advisor, and life advisor team.

Hindsight, as they say, is 20/20. I have witnessed and felt the anxiety of many market corrections. My first was the 1987 crash, followed by the technology bubble in 2000, the liquidity crisis that began in 2007, and the deep recession that marked 2008/2009. All of these corrections have provided me with a deeper understanding of not only who I am as an investor, but the overall industry. As a student of the business, I had a front‐row seat to how advisors and high‐net‐worth clients reacted to these volatile markets. So it begs the question, how can one avoid these setbacks? Some advisors respond to severe market corrections by underweighting their equity portfolios. However, the stock market's history for the past 200 years tells us betting against America is a mistake.

From a historical perspective, the equity market returned 11.7 percent from 1928‐2016. But we know the market is never “average.” Therefore, maintaining purchasing power is key to maintaining your lifestyle. Stocks have lost at least 10 percent of their value 23 times in the last 122 years. Understanding investors' risk tolerance is arguably the most important thing you can discuss with your clients on a regular basis. Waiting until a major correction occurs is an expensive way of getting to know what a client can handle. Some clients may only be comfortable with volatility somewhere around 20 percent. History and wisdom is always the best way to think about the future and how to create wealth. When Warren Buffett was asked about his secret of creating a $67 billion fortune, he said, “My wealth has come from a combination of living in America, some lucky genes, and compound interest.” As someone who's been invested in the market for the past 35 years I can tell you first hand that compound interest is indeed the secret—and avoiding big mistakes. The other major lesson we can learn from Warren Buffett is to stay in the market and ride its ups and downs. Furthermore, Buffett doesn't just buy stocks; he buys companies. Because even if you are smart enough to get out of the market at the right time, you also have to know when to get back in. Diversification is always your friend.

One of the best ways to add value for your clients is to reduce the noise around them. By noise, I am referring to the overload of information we receive on a daily basis. While some of the information is truly valuable and relevant to the client, much of it is written to stir the pot or create drama or even distract people from what's really going on. It's important that you know how to filter useful information from the noise. As their advisor, clients depend on you to help reduce their anxiety, not increase their blood pressure by providing noise that means nothing in the end. Historically, every four to six years we experience a 20‐plus percent market correction. You must guide your clients through these times of volatility.

After 35 years I have learned that markets cannot be timed with any consistency. I have also learned that for the past 100 years equities have provided substantially better returns than other asset classes. What does the future hold? Well, no one knows. What we do know is this: history favors a return to the mean. Therefore, if an investor doesn't have at least a five‐year time horizon, he probably has no business being in the equity market. As well, the world is getting more prosperous and emerging nations are experiencing growth of their middle class. We are living through a technological revolution that will fuel growth. Equities are needed to protect purchasing power. For many, being out of the market poses the biggest risk when it comes to portfolio construction. Far too many investors get scared out of the market at the worst time.

When I first started as an advisor in the early 1980s, I had a handful of clients who were wise investors and knew a great deal about building a portfolio. They understood why trying to time the market is a foolish thing to do and they knew the importance of dollar‐cost averaging. These clients would invest in high‐quality stocks on a regular basis, growing their overall portfolio. Over the years these clients became wealthy. I specifically remember one client, a New York police officer whose mother taught him how to invest in the market when he was in his twenties. As time went on he accumulated a net worth of over $4 million between some inheritance and smart investing. The market volatility didn't bother his generation of investors.

Today, advisors talk about goals‐based wealth management, aligning an investment strategy by goals based on a particular time horizon. Successful portfolio construction must be based on the client's needs, wants, and legacy. One way to think about structuring a portfolio is based on timeline segmentation. Long‐term portfolios are those looking 10 to 15 years out, intermediate‐term portfolios, 5 to 10 years, and near‐term portfolios, 6 months to 2 years. If you have been in the business for a few years, you have seen data showing the benefits of remaining in the market. For example, from 1996 to 2015, the S&P 500 returned 8.18 percent, if fully invested. Missing the 10 best‐performing market days during that period of time meant an investor's returns were cut by half to 4.49 percent. If an investor missed the 30 best days, his return declined to −0.05 percent. Trying to time the market is impossible. That's why a diversified portfolio can help you stay in the market and make the ride a little smoother.

From Stockbroker to Life Advisor

How did we move from the traditional account executive or stockbroker to financial advisor or wealth advisor? From the late 1970s and through the 1980s and 1990s, it was about firms manufacturing products and stockbrokers selling shares in those firms, be it stocks, bonds, closed‐end funds, or limited partnerships. A guideline—Rule 405—required that brokers determine the suitability of investments before making recommendations. At the end of the day, it was about selling and earning a commission on the transactions, and doing what you thought was in your client's best interest. Today, the financial world is moving toward a fiduciary standard in which an advisor occupies a position of special trust and confidence when working with clients to act with undivided loyalty to the client. This includes disclosure of how the financial advisor is to be compensated and any other conflicts of interest. Regardless of how the rules surrounding the fiduciary standard change going forward, the future will demand that the advisor be completely transparent and always put the client's interests first.

As with everything there are risks that come with investing and managing another person's wealth. One can't talk about putting the clients' interests first if one does not have the skill, knowledge, and competency to understand risk. Clients want to maximize returns on a risk‐adjusted basis. A little history on risk will serve us well, but for a deeper dive, I wholeheartedly recommend Against the Gods by Peter L. Bernstein, and, in my opinion, it should be mandatory reading for anyone in financial services.

The serious study of risk began during the Renaissance (1300–1700) when long‐held beliefs were challenged and new ideas were introduced. It was a time of religious turmoil, nascent capitalism, and a vigorous approach to science and the future. In 1654, the Chevalier de Méré, a French nobleman with a taste for both gambling and mathematics, challenged the famed French mathematician Blaise Pascal to solve a puzzle. The question was how to divide the stakes of an unfinished game of chance between two players when one of them is ahead. The puzzle had confounded mathematicians since the time it was posed some one hundred years earlier by the monk and mathematician Luca Paccioli. Pascal turned for help to Pierre de Fermat, a lawyer who was also a brilliant mathematician. The outcome of their collaboration was intellectual dynamite, resulting in the theory of probability, the mathematical heart of the concept of risk.

The theory of probability enabled people for the first time to make decisions and forecast the future with the help of numbers. Fast forward to 1952, when Harry Markowitz, a young graduate student at the University of Chicago, demonstrated mathematically why putting all your eggs in one basket is an unacceptably risky strategy. Tony will discuss Harry Markowitz in my interview.

The word risk derives from the early Italian word, risicare, which means “to dare.” In this sense, risk is a choice rather than a fate. The action we dare to take depends on how free we are to make choices. In his book, Against the Gods, Bernstein points out that persistent tension exists between those who assert that the best decision is based on quantification numbers, determined by the patterns of the past, and those who base their decisions on more subjective degrees of belief about the uncertain future. This push–pull dynamic has never been resolved and is inherent in understanding risk.

Helping a client understand risk beyond investments is helping the client make better choices and plan accordingly. The advisor of today and tomorrow is a life advisor, not a stockbroker selling a product. The biggest question you need to ask yourself is: What's the most efficient and cost‐effective way to manage your client's portfolio? What is your talent? Are you a stock picker? Or are you a great asset allocator and play the role of the quarterback, hiring and firing money managers? Outsourcing investment management for most advisors is simply the way to run a business and most importantly the client's best solution.

To explore how the investing landscape is changing, I conducted an interview with a friend and former colleague, Tony Davidow. Tony has over 30 years of experience in the industry. He began his career working for a family office, later worked for a large wealth management firm as an asset manager, and is currently serving as an asset allocation strategist for the Schwab Center for Financial Research. He is an award‐winning author and frequent speaker at industry conferences.

Rick: How has asset allocation and portfolio construction evolved over the last several decades, and how should advisors evolve their approach?

Tony: There are three macro‐trends that advisors will need to address in order to continue to grow their practices and meet their clients' needs: (1) advisors will need to understand and embrace the role and use of nontraditional investments, (2) advisors will need to incorporate active and passive investing, and (3) advisors will need to incorporate some form of forward‐looking tactical allocations.

Today's asset allocation needs to evolve beyond the old 60/40 portfolio (60 percent S&P 500 and 40 percent Barclays Aggregate Bond index). It used to be sufficient to use a basic stock, bond, and cash portfolio where your stocks provided growth, bonds provided income, and cash provided stability. However, the current market presents significant challenges for the 60/40 portfolio. Bond yields are at generationally low levels and stock returns will likely be below their historic norms.

In 1952, Harry Markowitz first introduced the concept of diversification, which later became the basis of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT). Markowitz's work concluded that an investor could reduce the overall risk of a portfolio by including investments that have low correlations to one another. Markowitz once called this “the only free lunch in finance.” In other words, diversification can deliver benefits over time at no additional cost.

Markowitz's research focused on diversification across a group of stocks. We now live in a global economy where companies sell goods and services around the world. The world is more complex, but fortunately we have more efficient ways of accessing the markets.

In order to reap the benefits of diversification, today's advisors need to expand the number of asset classes and include certain nontraditional investments. Stock allocations should include domestic large‐ and small‐cap and international and emerging markets, among others. Bonds should be diversified across Treasuries, corporations, high yield, and international and emerging markets debt, among others. Investing in commodities, real estate, and alternative investments can provide broader diversification.

Rick: With the expanding number of asset classes, it may seem daunting to clients and advisors. How do you suggest advisors explain the merits of these investments?

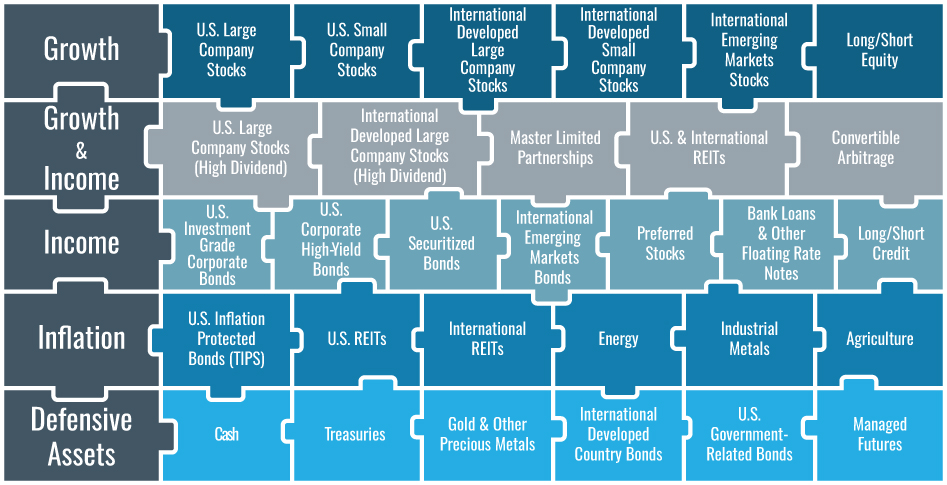

Tony: You're right. Investors are often intimidated by the unknown so we suggest changing the manner in which advisors introduce some of these new investment options. You can think of a portfolio as a series of puzzle pieces. Viewing each piece in isolation may seem confusing—but when put together the right way, the picture comes into focus.

A Portfolio Is Like a Puzzle

Investors understand goals and outcomes. If we change the discussion to outcomes, it's easier for investors to understand the role each investment plays in putting the pieces of the portfolio together. Growth will come primarily from stocks—U.S. large and small, international and emerging markets. Growth and income will come from dividend‐paying stocks here and abroad, plus master limited partnerships (MLPS) and real estate investment trusts (REITs). Income will come primarily from fixed income—Treasuries, corporates, high yield, and so on. Certain investments have been effective in hedging the impact of inflation, like TIPS, REITs, and some commodities. Cash, gold, and Treasuries can serve as defensive assets. Not only is this approach easier for clients to understand but it helps in managing expectations.

Rick: For many years I've heard the debate “active” versus “passive,” but you're suggesting that there is a role for both. Please explain your point of view. I know that you've done a lot of research on “smart beta” strategies. Are they active or passive?

Tony: For years, academics and advisors have debated the merits of “active” and “passive” strategies. Active management generally means a mutual fund or separately managed account (SMA). Passive management is generally in the form of an index‐based mutual fund or exchange‐traded fund (ETF).

The critics of active management would point to their difficulty in outperforming their passive benchmarks. Active managers would often counter with their skill in selecting winning companies, and avoiding the losers.

The popularity of indexing exploded after 2008 as advisors were challenged to justify the value of active management during the financial crisis. Most active managers were not able to outperform their benchmarks during the 2008 downturn. Today, there are over $3 trillion in ETF assets under management globally, providing exposure to virtually every segment of the market. Most of the major indexes, and most of the ETFs in the marketplace, are market‐cap oriented, meaning they provide the largest weighting to the largest companies regardless of their financial strength. One might say a market‐cap index “overweights the overvalued stocks and underweights the undervalued stocks.”

The first generation of indexing was focused on replicating a particular benchmark in a cost‐effective fashion, also known as “cheap beta.” The second generation of indexing sought to improve upon the market experience, either increasing the return potential or reducing the risk. These strategies are often referred to as “smart beta” or “strategic beta.” Smart beta strategies often leverage academic research showing that you could improve the market experience by breaking the link with price (i.e., the dependency on size). For example, fundamental index strategies screen and weight securities on such factors as sales, cash flow, and dividends + buybacks.

Smart beta strategies employ different weighting methodologies and periodically rebalance back to the index weight. A few of the more popular smart beta strategies are equal‐weight, momentum, low volatility, quality, and fundamental index strategies. While they are often grouped together, they are quite different in the manner in which they screen and weight securities, as well as the corresponding results. We view these strategies as a complement to both market‐cap and active management.

Our research has shown that many of these strategies have historically delivered excess returns relative to their market‐cap equivalents. Certain market environments may reward one strategy versus another. In 2015, momentum was the best performing smart beta strategy as the market was dominated by the FANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google). In 2016, fundamental was the best performing strategy as the markets focused on valuations. We favor fundamental index strategies due to the robustness of the research and the “live” experience of these strategies.

Rick: How do you suggest advisors combine these types of strategies?

Tony: We believe that you need to start by defining the role that each of these strategies plays in a portfolio. We focus on four key levers in building portfolios—tracking error, loss aversion, alpha, and cost—and then consider how to weight our strategies across market segments. Market‐cap strategies have little or no tracking error and are typically the low‐cost solution. Fundamental strategies have historically delivered alpha across market segments, and are generally more cost effective than active managers. Active managers are best equipped to deal with investors' concerns about loss aversion as they can play defense. Not all are active managers, but many can deliver better downside protection.

| Domestic Large Cap | Domestic Small Cap | Inter‐national Large Cap | Inter‐national Small Cap | Emerging Markets | |

| Market Cap | 30% | 25% | 20% | 20% | 20% |

| Fundamental | 50% | 50% | 30% | 30% | 30% |

| Active | 20% | 25% | 50% | 50% | 50% |

In the most efficient markets (Domestic Large Cap) [see table], we would allocate 50 percent to fundamental indexing, 30 percent to market‐cap, 20 percent to active management. We don't see a lot of persistence in active managers outperforming the passive options. In the least efficient markets (Emerging Markets), we'd allocate 50 percent to active managers, 30 percent to fundamental, and 20 percent to market‐cap strategies. Here we believe that there should be some skill in identifying strong companies and avoiding weak ones.

Rick: With the markets' ever‐changing nature, how should advisors respond? Should they try to time the market or weather the storm?

Tony: In recent years, there have been a number of events that have caused significant market disruptions: concerns about Greek debt default, Central Bank intervention, Chinese economic slowdown, and Brexit, to name a few. As a result of these dramatic events, investors are demanding insights and advice about how to navigate these challenging waters. Sometimes the best advice is to do nothing, but other times it may be prudent to make subtle shifts in portfolios. We believe in the value of being more tactical in allocating assets. We're not suggesting being all‐in or all‐out of the markets, but rather making subtle shifts at the margin to help position portfolios. You may want to overweight an undervalued segment of the market or underweight an asset class that has become expensive. You may want to avoid markets with extreme volatility or tactically overweight an interesting investing opportunity.

Being more nimble and flexible may help keep your client engaged in good times and bad. It's also an opportunity to demonstrate your insights and outlook.

Rick: In light of the rapid growth of automated advice (also known as “robo‐advice”), your insights show the value of a personal relationship and the ability to react in real time to the ever‐changing environment.

Tony: Automated advice shouldn't be viewed as a threat but as an efficient means to scale your business. Firms can either embrace technology, or determine how best to utilize it, or risk becoming obsolete. Technology can help you scale your practice and reach a generation of investors who have become dependent on technology solutions for virtually everything.

It is the combination of technology and personal touch that will resonate with clients. Successful advisors will evolve the way they do business and embrace changes in a positive fashion. While certain things can be automated, personalized advice can never be commoditized. Of course, the balance is how to grow your business while retaining a personal relationship with the client.

Don't Second‐Guess the Masters

Successful advisors, leaders with a growth mindset, don't overcomplicate anything. They apply the same basic investment rules to growing their own practice as well as to managing the assets of their clients. A core principle is simply “don't lose,” because if you're down 50 percent, you need to be up 100 percent to recoup that 50 percent loss. Said differently, protect the downside because making up big losses becomes very difficult. Tax efficiency makes a difference. Diversify across different asset classes and within asset classes, and dollar‐cost average. John Templeton and Warren Buffett, over the course of their careers, have developed a set of simple rules for investment success. Why should we have to make things more complicated than the two greatest investors of all time?

Simple Rules for Investment Success

- Invest for maximum total real return.

- Invest, don't trade or speculate.

- Remain flexible and open‐minded about types of investments.

- Diversify. In stocks and bonds, as in much else, there is safety in numbers.

- Listening to market predictions is a waste of time.

- Don't panic.

- Learn from your mistakes.

- Outperforming the market is a difficult task.

- An investor who has all the answers doesn't even understand all the questions.

Wealth management is based on the client's total financial picture. It's not about just managing the investment process; it's following an eight‐step process that can help your clients have a better experience and higher probability of achieving their goals:

- Help your clients understand what comprehensive wealth management is versus just investing. (However, if you don't offer wealth management services, be honest and let the prospect know you only specialize in investment management.)

- Help them understand why a team is important to achieve their goals.

- Help them understand the investment process and financial planning process.

- Help them with estate planning, legacy planning, and so on.

- Help them manage their debt and cash flow and establish overall good habits on budgeting and saving.

- Help them with retirement planning needs, life insurance, health and long‐term care, and so on.

- Help them manage the tax liabilities.

- Help them with succession planning (as needed and appropriate).

The team should have one quarterback—the wealth advisor or financial advisor—along with a planning advisor, a trust advisor, an estate planning lawyer, a tax advisor, an accountant or CPA, and an insurance specialist.

In terms of the advisors managing money, clients want value and the following eight steps provide real value:

- Help your clients define their short‐ and long‐term goals.

- Help them fully understand your process and investment philosophy.

- Help them with asset allocation and diversification across different asset classes.

- Help them dollar‐cost average.

- Help them rebalance.

- Help them with behavior coaching, emotional resistance.

- Help them with tax efficiency.

- Help them monitor the overall plan and make necessary changes.

“In my nearly 50 years of experience in Wall Street, I've found that I know less and less about what the stock market is going to do but I know more and more about what investors ought to do.”

—Benjamin Graham