53

Governance of Small and Medium-Sized Entities

Jo Iwasaki MA FCA ACCA

Investor Relations, Helsinki Capital Partners; and Past Secretary, Global Forum on Governance, Risk, and Performance, ACCA

Introduction

As a group, small and medium-sized entities (SMEs) are a sector that contributes significantly to national economies. Bodies such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank recognize the importance of SMEs, which account for the largest proportion of companies globally. Their impact on employment is also substantial: “They play an outsized role in developing economies, where they account for about half of employment and the majority of jobs created.”1

The challenge is that their growth, productivity, and entrepreneurship are often compromised compared with those of larger companies. Although their economic performance is monitored closely because they affect national economies,2 SMEs have underlying challenges: Governance is one of them.

What Are SMEs?

The definition of SMEs generally depends on size-based criteria, such as turnover, balance sheet total, and headcount, or a combination of these. Thresholds vary from country to country, depending on the size and other characteristics of the national economy. For example, the OECD defines SMEs as firms employing up to 249 persons, with a further breakdown into micro (1–9), small (10–49), and medium (50–249).3

Table 53.1 Criteria Used to Define Business Size in the EU

| Company Category | Headcount | Turnover or Balance Sheet Total |

| Medium-sized | <250 | Turnover ≤ €50m or Balance sheet total ≤ €43m |

| Small | <50 | Turnover ≤ €10m or Balance sheet total ≤ €10m |

| Micro | <10 | Turnover ≤ €2m or Balance sheet total ≤ €2m |

Alternatively, the European Union (EU) combines different size-based categories, as shown in Table 53.1.4

Another definition of SMEs appears in Section 1 of International Financial Reporting Standard for Small and Medium-sized Entities (“IFRS for SMEs”). The IFRS for SMEs is an accounting standard specifically developed for SMEs and monitored by the IFRS Foundation. Individual countries determine the applicability of this standard but there is an overarching definition of SMEs as entities that:

- Do not have public accountability, and

- Publish general purpose financial statements for external users.

An entity has public accountability, as defined by the IFRS for SMEs, if:

- Its debt or equity instruments are traded in a public market or it is in the process of issuing such instruments for trading in a public market, or

- It holds assets in a fiduciary capacity for a broad group of outsiders as one of its primary businesses.5

These criteria indicate that there are qualitative aspects to SMEs, particularly in their role in relation to the capital markets and corresponding public accountability. Therefore, the size-based definition covers only some of their characteristics.

Governance Codes and Standards for SMEs

Primarily owing to their size but also to their noninvolvement in capital markets, SMEs are usually outside the scope of formal governance requirements. As a result, it is rare to find mandatory governance requirements for SMEs. This is evident from the fact that SMEs do not see governance requirements as among the regulatory and administrative burdens otherwise deemed the most important factors affecting SMEs and start-ups, presenting legal barriers to entry and increasing their compliance costs.6

This does not mean that governance has less relevance for SMEs than for their larger counterparts. On the contrary, governance is relevant to any entity that has a duty toward parties affected by its stewardship, whether those affected (“stakeholders”) are external or internal. This is because governance “helps to protect the rights and interests of shareholders and, increasingly, those of other stakeholders, providing a framework for effective monitoring of management actions and performance and for encouraging better business results.”7

Challenges in policymaking over SME governance arise because listed companies, in which ownership and management are separate but which also owe accountability to the public due to their listed status, have driven the development of governance frameworks. Among SMEs, where owners and managers are often the same people, the agent-principal issue is often absent.

Adding to this limited relevance of established governance frameworks, the cost-benefit balance of good governance is hard to prove. This has often reduced the apparent need for good corporate governance and so the topic has been largely ignored by SMEs. Even so, codes and standards have been published that are applicable or relevant to SMEs. The next section reviews some of these that are widely applicable or recently launched.

Governance Standards and Codes Applicable to All Types of Organizations, Including SMEs

Most corporate governance standards and codes are specifically developed for, and addressed to, publicly listed companies but they vary in application. Some allow application by entities other than public companies, or may not specify the types of entity to which they apply, or may apply to all companies.

The term “code,” where used, generally implies a form of “soft” law that sets out best practice, used on a so-called “comply-or-explain” or “apply-or-explain” basis.8 This contrasts with “hard” law, such as company law, which is enforceable and carries penalties for noncompliance.

This does not exclude others from applying the codes and some may encourage application by companies that are outside their scope. An example of this is the UK Audit Firm Governance Code, developed originally in 2007 by an independent working group at the invitation of the UK Financial Reporting Council (FRC), the industry regulator, to be applied to public practices auditing 20 or more listed companies. The Audit Firm Governance Code is broadly based on the UK Corporate Governance Code, applicable to companies with a premium listing.9

While SMEs may also adopt a code issued for listed companies, in practice such adoption takes place mostly among large companies that are approaching a listing stage, or entities whose reputation and public accountability are under scrutiny. This is not the case for SMEs: Governance requirements related to capital markets are largely irrelevant. Furthermore, owing to the size and simple structure of SME organizations, principles such as board independence and committee structure, though fundamental to large listed companies, are often impractical or even prohibitive. Finally, to enable any meaningful application, the drafting of codes need to be set at a high level or be principles-based to accommodate the wide variety of size, form, and activities of SMEs.

An example of a code that applies to all organizations, regardless of their form of incorporation or size, is South Africa's King IV Code.10 The King Report on Corporate Governance was first issued in 1994 by the Institute of Directors in South Africa, and to date there have been four revisions.

The principles of King IV apply to all SMEs, as to all large and listed companies. SMEs are defined in Part 6.5 Supplement for small and medium enterprises within King IV. The Code explains the rationale for including SMEs within its scope as follows:

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are the drivers of a growing and inclusive economy, and of societal transformation SMEs need to be innovative and entrepreneurial, and open to technological change and productivity growth Good corporate governance contributes to the success of an SME, as it enhances the functioning of its leadership structures and helps the governing body to govern in such a way that the SME meets its strategic objectives.11

The principal idea behind the broad applicability of King IV is its “mindful application.” King IV explains the benefits of corporate governance for specific sectors, allowing organizations to interpret and apply the Code in a way that is appropriate for them. To highlight this point, the Code discusses governance outcomes: ethical culture, effective control, good performance, and legitimacy. Application of principles should ultimately help organizations achieve these outcomes; compliance means little in itself.

Furthermore, leading practices set out in King IV are meant to be scaled in accordance with size of turnover and workforce, amount of resources, and extent and complexity of activities, enabling proportionality.

Governance Standards and Codes Developed for Non-Listed Companies

The European Confederation of Directors' Associations, also known as ecoDa, is a not-for-profit association acting as the European voice of board directors. In 2010, ecoDa published a set of 14 principles of good governance for unlisted companies. Corporate Governance Guidance and Principles for Unlisted Companies in Europe takes into account “the degree of openness, size, complexity and level of maturity of individual enterprises” in adopting good practice.12

As many unlisted companies are owned and controlled by individuals and families, the Guidance and Principles starts from the position that the primary concern should not be the relationship between boards and external shareholders or with a focus on compliance with formal rules and regulations. Instead:

it is about establishing a framework of company processes and attitudes that add value to the business, help build its reputation and ensure its long-term continuity and success.13

The main beneficiaries of good corporate governance, according to ecoDa, are shareholders of private companies. This is because they often have limited ability to sell their ownership stakes and are therefore committed to staying with the company for the medium to long term. The Guidance and Principles also note that even unlisted companies will have to be attentive to fulfilling their corporate responsibilities toward their stakeholders as the societal scrutiny over businesses increases.

One of the critical concerns ecoDa Guidance and Principles point out is that a company is not an extension of the personal property of the owner. This is important for private companies as the founder of a company can be a controlling shareholder and often holds an important position in the management.

To enable the application by a wide range of companies, the Guidance and Principles introduces its 14 principles in two phases: Phase 1 (principles 1–9) applies to all kinds of unlisted company, regardless of size or complexity while Phase 2 (principles 10–14) is more relevant to larger and more complex companies, including those seeking to prepare for a future listing.

Phase 1 principles include the establishment of constitutional documents, a board responsible for long-term success and oversight, and shareholder engagement. These do not necessarily require detailed, bureaucratic procedures and can be adopted by small companies. In practice, ecoDa notes, the key challenge is that the leadership of the company that introduces governance principles needs to be fully convinced of the benefits of doing so. This is because even some of fundamental principles, such as transparency and checks and balances, may require practices unfamiliar for some leaders, such as owner-managers.

A key characteristic of Phase 2 principles is a clear and explicit separation of management and oversight. Independent directorship, balance and diversity, and evaluation of board and individual directors are introduced in Phase 2. The Guidance and Principles call this a “landmark event in the evolution of an unlisted company … an irreversible step towards good governance.”14 These principles are primarily addressed to larger and more complex entities, unlisted companies with significant external financing, and unlisted companies aspiring to a public listing.15

The development of codes for unlisted companies may correspond with changes in the political and regulatory environment. Wates Corporate Governance Principles for Large Private Companies, published by the UK FRC in 2018, is intended to help large private companies that have come under new obligations by The Companies (Miscellaneous Reporting) Regulations 2018 (effective from 1 January 2019).16

The UK government published a Green Paper on Corporate Governance Reform in November 2016. Introducing a corporate governance framework for large private companies was one of the key issues, and the rationales given in the Green Paper can be summarized as below.

- Good governance is about more than the relationship between the owners and the managers of a business. Other stakeholders, including employees, customers, supply chains, and pension fund beneficiaries, also suffer when a private company fails.

- Society has a legitimate expectation that companies will be run responsibly in return for the privilege of limited liability, irrespective of their size and incorporation status.

- There has been an increase in the number of private companies that are outside the scope of public scrutiny and formal corporate governance discipline associated with listed companies.

- It is in the interests of businesses themselves to have good corporate governance that provides confidence to stakeholders and helps build reputation and contribute to long-term success.17

Following the public consultation, the UK government introduced new regulatory requirements for large private companies to state in the directors' report which corporate governance code the company applied in the financial year and how it had done so, including any departures from that code's requirements.

The FRC set up a coalition of trade and industry, investors, workers, and professional bodies, as requested by the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industry Strategy, in January 2018 to develop a set of corporate governance principles for large private companies.18

Many supported strengthening corporate governance standards for large private companies on the basis that “the social and economic impact of large private companies can be as great as that of listed companies and can pose similar risks for pensioners, employees, supply chains, local communities and others.”19 The definition of “large private companies” in the government regulations certainly excludes SMEs.20 Nonetheless, except for the issue of public accountability, both the basic premises and the fundamental principles appear to be no less relevant to SMEs than to large private companies:

[G]ood governance can go beyond the relationship between the owners and the managers of a company, and … there are other stakeholders, including employees, suppliers and customers with a strong and legitimate interest in the way a company is run.21

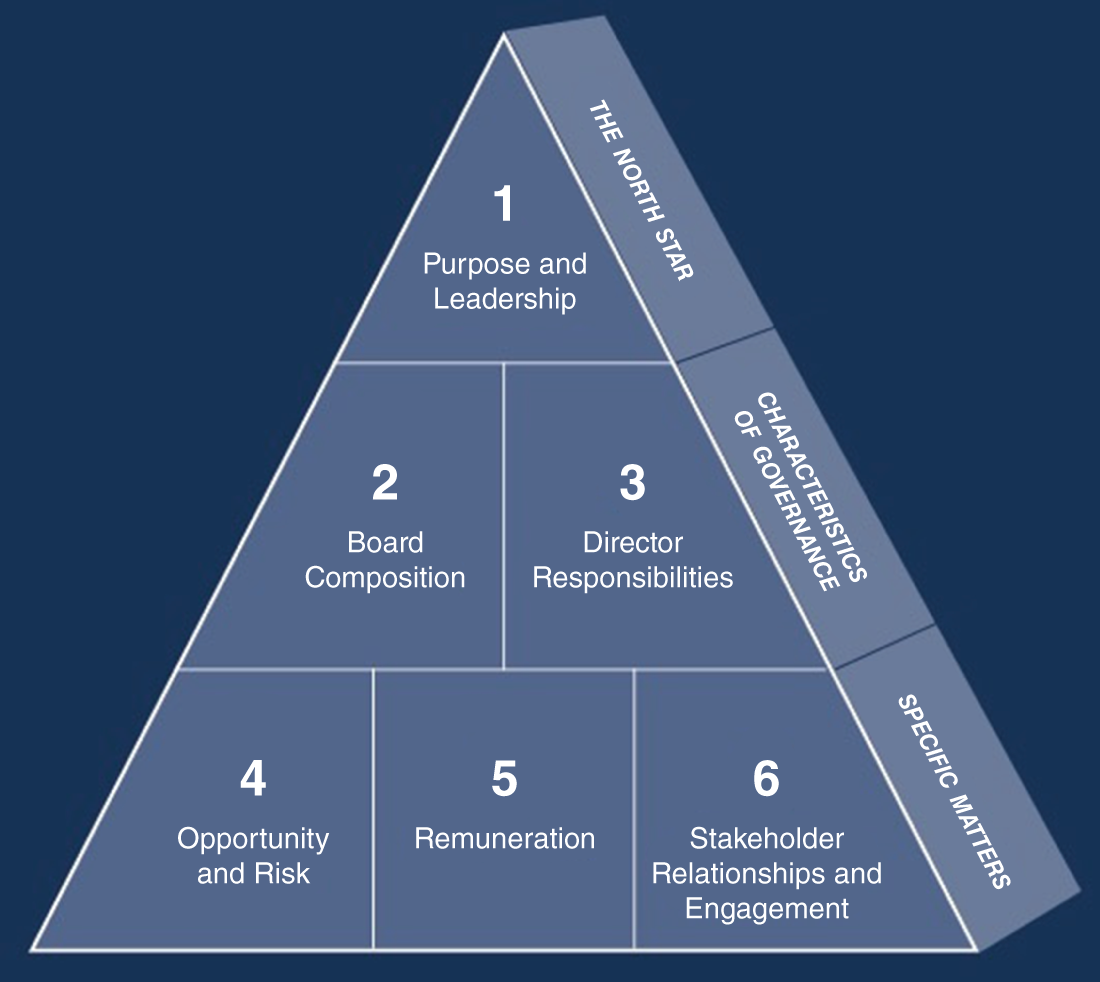

Six of the Wates Principles are extracted and set out below.

- Purpose and Leadership—An effective board develops and promotes the purpose of a company and ensures that its values, strategy, and culture align with that purpose.

- Board Composition—Effective board composition requires an effective chair and a balance of skills, backgrounds, experience, and knowledge, with individual directors having sufficient capacity to make a valuable contribution. The size of a board should be guided by the scale and complexity of the company.

- Board Responsibilities—The board and individual directors should have a clear understanding of their accountability and responsibilities. The board's policies and procedures should support effective decision-making and independent challenge.

- Opportunity and Risk—A board should promote the long-term sustainable success of the company by identifying opportunities to create and preserve value and establishing oversight for the identification and mitigation of risks.

- Remuneration—A board should promote executive remuneration structures aligned to the long-term sustainable success of a company, taking into account pay and conditions elsewhere in the company.

- Stakeholder Relationships and Engagement—Directors should foster effective stakeholder relationships aligned to the company's purpose. The board is responsible for overseeing meaningful engagement with stakeholders, including the workforce, and having regard to their views when making decisions.

Some of the principal ideas, such as having a board separate from the executive team and observance of independence, may be achievable in effect rather than form in the SME context. In any case, none of the ideas underlying the principles should be disregarded as irrelevant or impractical by the majority of smaller companies.

Figure 53.1 shows the hierarchy of the different principles and how they fit into company structure. The overall direction comes from Principle 1, purpose and leadership. Principles 2 and 3 set out key characteristics of the governance structure. At the third level are the specific areas in which private company governance standards need to be improved.

The Wates Principles are supported by the apply-or-explain approach as in King IV, in contrast with the UK Corporate Governance Code, which adopts a comply-or-explain approach. Each of the Wates Principles is underpinned by guidance, assisting companies in explaining how they have applied each principle appropriately to their circumstances and how this is intended to achieve the desired outcome as set out in each principle.

FIGURE 53.1 “The Six Principles”

Source:FRC (2018), p. 10.

Governance Material Specific to SMEs

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) (a member of the World Bank Group), which aims to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity globally,22 provides investment advice and asset management to help companies in developing countries. It uses its expertise in corporate governance to help “companies operate more efficiently, improve access to capital, mitigate risk, and safeguard against mismanagement. [Corporate governance] makes companies more accountable and transparent to investors and gives them the tools to respond to stakeholder concerns.”23

IFC provides materials developed specifically for SME governance, arguing that SMEs could benefit from introducing certain governance principles to help their competitive survival and growth. It explains the business case as follows.

The extensive body of research shows that well-governed companies demonstrate substantially better long-term financial results and grow faster and more sustainably. SMEs interested in attracting investors can use better governance as a core value proposition. Various providers of risk capital for SMEs, such as private equity and venture funds, understand that good governance means more security and better return on investment.24

IFC's SME Governance Methodology is an in-house tool that IFC uses to analyze the stages of SME growth from start-up to maturity and to identify the various opportunities and challenges associated with each stage. In doing so, IFC aims to differentiate its approach from “[t]raditional guidance for SMEs [that has] amounted to ‘simplified’ versions of corporate governance practices recommended for larger companies” by helping them “identify governance gaps in their own companies and to find practical solutions that will benefit their business and promote its sustainable growth.”25

The approach focuses on the following key topics, of which some are also found in established governance guidance addressed to large listed companies:

- Evolution of strategic decision-making and management practices

- Practices that attract, motivate, and empower staff of high caliber

- Succession planning to minimize key-persons risk

- Internal controls to manage business risks

- External advisers and advisory board

- Setting up an effective board of directors

- Governance of family businesses26

What Does Governance Mean to SMEs?

Having reviewed existing standards and codes on SME governance, this section considers the views of smaller businesses on good governance.

In 2018, the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) surveyed approximately 500 people globally in senior positions in SMEs. The purpose of the research was to understand their views on, and practices of, good corporate governance.27 The respondents consisted of representatives of 18 percent micro, 36 percent small, and 46 percent medium-sized companies, and 96 percent of respondents were qualified accountants or similar, whose understanding of financial and related regulatory matters may have influenced the findings.28

The survey questions explored four themes, developed on the basis of existing governance codes and standards. The survey excluded specific questions related to remuneration, which is more often than not associated with corporate governance debates about large, often listed, companies.

The four themes explored were:

- Vision, strategy and leadership

- Leadership competence

- Accountability and reporting

- Connecting with employees

Interviews and focus group discussions complemented the survey outcome by providing narratives.

The survey focused on practical aspects of governance, for example, leadership responsibility in promoting long-term success, and the processes and procedures set up to support this endeavor. Transparency of governance arrangements, such as reporting, is important in attracting much-needed external funds, but there is otherwise limited incentive for SMEs unless required by regulation.

It is about leadership directing the organisation to long-term prosperity, and thus achieving the outcomes that the organisation has pledged. In doing this, the leaders need to introduce oversight mechanisms; align processes and procedures with the purpose of the organisation; demonstrate to internal and external stakeholders their commitment and bring them along on the journey towards prosperity and success; and exercise control to ensure that resources are used for the maximum impact.29

The research findings are broadly categorized in two groups: one related to the internal working of the organization and the other related to the interaction with stakeholders external to the organization.

Governance as Direction Setting and Leadership

The research found that, for governance, the effectiveness of internal functions greatly depends on leadership's establishment of a clear vision, supported by strategy, control, and processes. The effectiveness of the functions depends also on people involved with the business, particularly staff, and having them buy into the vision, supporting strategy, controls, and processes.

A large majority of survey respondents said that their organization had a vision which was longer than three years. In contrast with vision, 65 percent of total respondents said their strategy was for between one and three years. While both are subjective concepts, “vision” is often seen as linked with mission, values, and organizational purpose, in contrast with “strategy,” which relates to allocating resources and monitoring the outcome with a view to optimizing the impact. The time frame for both vision and strategy was shorter among micro-entities, possibly reflecting their smaller financial resources than those of larger firms.

Among all SMEs, the CEO or owner/manager plays an important leadership role, but they are increasingly supported or possibly replaced by senior management/executive teams as the organizations grow. Nearly half of the organizations surveyed did not invite external parties to their strategy discussion and this was particularly evident among micro-entities. Where they did so, their main point of contact was a consultant or independent advisor, followed by a professional accountant, external investor, or founder who is outside the executive team.

When asked about the reason for inviting external parties to strategy discussions, respondents most frequently cited the following three motives:

- The external party's experience and knowledge of the industry/sector

- Obtaining constructive criticism/independent perspective

- Obtaining advice on the SME's growth strategy

These reasons broadly mirror those cited in corporate governance frameworks for larger or listed companies, which call for the introduction of nonexecutive directors for independent oversight. Although no formal requirements are established, SMEs appear to recognize the need for additional skillsets that are often outside those of the owner-manager and executive team.

As regards the leadership team's skillsets, while the majority said that their leadership team had a process for ensuring that its members had a broad range of skillsets, the method of assessment tended to be informal, such as internal discussion. The use of more formal methods, such as using a skills matrix, was limited and 37 percent of respondents reported that their organization had not considered the balance of its leadership skillset for reasons such as not having had any issues due to a lack of specific skills, non-urgency, or limitation in their financial resources.

Governance as Transparency and Engagement

The degree of external transparency and engagement with stakeholders was explored through questions on reporting and employee engagement.

A large majority of respondents from medium-sized companies said that their organization presented its financial position and prospects to external parties, typically banks and external funders, followed by owners and shareholders who were not part of the internal leadership team. Among micro-entities, by contrast, up to one-third said that they did not share the organization's financial information. Correspondingly, fewer than one-third of micro-entity leaders shared financial information with banks and fund providers.

When asked whether they presented information other than financial, SMEs responded that they most frequently shared information related directly to business and resources: budget and forecast information, followed by sales and business performance measures. Among micro-entities, 41 percent did not present anything other than financial information. It was noted that across SMEs of all sizes, 11 to 14 percent prepared sustainability reports and 22 to 30 percent prepared regulatory reports.

Connecting employees with the vision and strategy of the business is fundamental to small businesses, particularly those that operate with a small team, where it is usual that staff members “step into each other's shoes” where staff shortage requires. A good understanding of the business vision and strategy helps them appreciate each other's tasks.

Many organizations communicate with their employees in team meetings. The survey showed that this was slightly less common among micro-entities than among larger entities, which may indicate that, where everyone is sitting in the same room, they consider a formal “team meeting” unnecessary because informal meetings happen regularly. Larger organizations use written communication more frequently. The use of the annual general meeting or formal meeting is predictably very limited among micro-entities. Use of online platform and mobile chat was infrequently cited, although possibly these were used for instant and spontaneous conversations, rather than for communicating strategy.

Employee incentives were mainly financial (e.g., pay rise, bonus) among companies of all sizes, although professional development opportunities(e.g., training and qualifications) and promotion/new responsibilities were used often, by both small and medium-sized entities but not by micro-entities.

FIGURE 53.2 “Interaction with the Business Environment”

Source: ACCA (2018), p. 7.

ACCA research shows how these findings interact (see Figure 53.2). The triangle made up of three circles with a leadership in the middle shows a skeleton of an organization: For a robust organization, it is essential that vision, strategy, and people are well connected. Leadership plays a vital role in bringing together these drivers to optimize the effectiveness of each one.

The gray surround represents the dynamic aspect of the organization, involving both external and internal stakeholders. To be successful, a business must:

- Nurture its relationship with external stakeholders, strongly demonstrating that the business is implementing its vision through a sound strategy.

- Align rewards and opportunities for employees with its strategy; because people are one of the most precious resources for businesses, leaders need to understand how staff contribute to the strategy and reward them in line with business success.

- Stay flexible, adaptable, and resilient: Where all parties, both internal and external are aligned to the future of the business, they will collaborate, support, and complement each other better, and share knowledge. This contributes to the organization's viability.

Conclusion: Is Governance Relevant for SMEs?

Good governance for SMEs is certainly relevant: As shown by the above research, SMEs adopt, or are aware of, practices that are in line with good governance.

The main challenge is the lack of practical guidance that is detailed enough to be helpful without being inflexible. The apply-or-explain approach adopted by King IV and the Wates Principles makes apparent sense, but its mechanism hinges on reporting. For now, external communication of governance practices is unlikely to be at the forefront of the minds of SME leaders.

Communication of benefit is also important. It is difficult to quantitatively prove the benefit of good governance—whether for large listed companies or SMEs—and neither is the negative impact of the lack of good governance instantly visible. The consequence of this is that SMEs often see “governance” as something to be addressed in the future when they grow in size, or a matter to be addressed only if there is an issue.

Promoting good SME governance is a task for policymakers, industry leaders, and fund providers alike: A large amount of investment is going into the SME sector as the dynamo of a viable economy, and resource should produce optimum output. Furthermore, innovation takes place in SMEs as well as large companies: If good ideas are wasted owing to poor governance, that is a loss to society as a whole as well as to entrepreneurs and their immediate stakeholders.

About the Author

Jo Iwasaki, MA, FCA, ACCA, is a qualified accountant with an extensive research background in corporate governance, organizational culture, and risk. Jo has published a wide range of related topics, including governance principles, board responsibilities, and diversity. She enjoys engaging with and learning from stakeholders—directors, investors, professional accountants, and researchers.

Jo today works from Finland, at Helsinki Capital Partners (HCP) in investment relations. HCP is one of a handful Benefit Corporations (B Corps) (https://bcorporation.net/about-b-corps) in financial services and the only one in Finland.

Notes

- 1. The World Bank, 2016. New Evidence Shows Way Forward for SME Growth and Job Creation. 30 November 2016. Accessed on 31 December 2018. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/11/30/new-evidence-shows-way-forward-for-sme-growth-and-job-creation.

- 2. OECD's study series focuses on SME entrepreneurship, focusing on themes and countries. OECD, 2010. OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship. Accessed on 31 December 2018. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/industry-and-services/oecd-studies-on-smes-and-entrepreneurship_20780990?_ga=2.251607554.505237085.1546279539-112478397.1468573079.

- 3. OECD, 2017. Enhancing the Contributions of SMEs in a Global and Digitised Economy, page 4. Accessed on 7 January 2019. https://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/C-MIN-2017-8-EN.pdf.

- 4. European Commission, What Is an SME? Accessed on 31 December 2018. http://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/business-friendly-environment/sme-definition_en.

- 5. International Accounting Standards Board (IASB®), 2009. IFRS® for SMEs (PDF copy), page 10. London: IASC Foundation.

- 6. See, for example, OECD, 2018. Improving the Business Environment for SMEs Through Effective Regulation: Policy Note. Accessed on 31 December 2018. https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/ministerial/documents/2018-SME-Ministerial-Conference-Parallel-Session-1.pdf.

- 7. ACCA, 2015. Governance for All: The Implementation Challenge for SMEs, page 3. Accessed on 31 December 2018. https://www.accaglobal.com/content/dam/acca/global/PDF-technical/small-business/ea-governance-for-all.pdf.

- 8. Chris Pearce, “Trends in Corporate Governance.” The Handbook of Board Governance. Ed. Richard Leblanc with John Fraser. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2018. N1 and 2, page 68.

- 9. FRC, 2016. Audit Firm Governance Code (Revised 2016). Accessed on 7 January 2019. https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/8e2026c0-cac0-4faa-8326-4713511f139a/Audit-Firm-Governance-Code-July-2016.pdf.

- 10. Institute of Directors, Southern Africa, 2016. King IV: Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa. Accessed on 2 January 2019. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iodsa.co.za/resource/collection/684B68A7-B768-465C-8214-E3A007F15A5A/IoDSA_King_IV_Report_-_WebVersion.pdf.

- 11. Ibid., page 103. See “Section 2: Scope,” which defines SMEs “as a private for-profit company which has a public interest score of at least 350 calculated in terms of regulation 26(2) of the Companies Act, 2008.” The calculation of the public interest score is available from the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission. Public Interest Score: How to Calculate the Public Interest Score (PIS) of a Company or Close Corporation. Accessed on 2 January 2019. http://www.cipc.co.za/index.php/manage-your-business/compliance-and-recourse.

- 12. ecoDa, 2010. Corporate Governance Guidance and Principles for Unlisted Companies in Europe, 2010, page 6. Accessed on 4 January 2019. http://ecoda.org/uploads/media/GUIDANCE_-_2010_CG_for_Unlisted_-_EU.pdf.

- 13. Ibid., page 7.

- 14. Ibid., page 25.

- 15. Ibid., page 43.

- 16. The Companies (Miscellaneous Reporting) Regulations 2018. Accessed on 5 January 2019. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2018/9780111170298.

- 17. Department for Business, Energy & Industry Strategy, 2016. Corporate Governance Reform: Green Paper, pages 43–44. Accessed on 7 January 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/584013/corporate-governance-reform-green-paper.pdf.

- 18. Financial Reporting Council, 2018. Wates Corporate Governance Principles for Large Private Companies. Accessed on 6 January 2019. https://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/31dfb844-6d4b-4093-9bfe-19cee2c29cda/Wates-Corporate-Governance-Principles-for-LPC-Dec-2018.pdf. Full membership of the coalition group is available from page 3.

- 19. Department for Business, Energy & Industry Strategy, 2017. Corporate Governance Reform: The Government Response to the Green Paper Consultation. Accessed on 6 January 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/640470/corporate-governance-reform-government-response.pdf, page 37.

- 20. The new corporate governance requirements of The Companies (Miscellaneous Reporting) Regulations 2018 specify that “large private companies” are those that satisfy either or both of the following conditions: (a) more than 2,000 employees, and (b) a turnover of more than £200 million and a balance sheet of more than £2 billion.

- 21. Corporate governance reform: The government response to the green paper consultation, page 36. Accessed on 6 January 2019.

- 22. International Finance Corporation, Our Governance, Accessed on 1 January 2019. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/corp_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/about+ifc_new/IFC+Governance.

- 23. International Finance Corporation, Corporate Governance: Overview. Accessed on 1 January 2019. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/Topics_Ext_Content/IFC_External_Corporate_Site/IFC+CG.

- 24. International Finance Corporation, Small and Medium Enterprises. Accessed on 1 January 2019. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/ifc+cg/topics/small+and+medium+enterprises.

- 25. International Finance Corporation, Corporate Governance and Small and Medium Enterprises. Accessed on 1 January 2019. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/e4267212-baf6-401e-9c4e-165eb3e41908/CG+SMEs+fact+sheet.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

- 26. Ibid. Extracted from the web page.

- 27. ACCA, 2018. How Vision and Strategy Helps Small Businesses Succeed: Governance Needs of SMEs. Accessed on 6 January 2019. https://www.accaglobal.com/content/dam/ACCA_Global/professional-insights/Governance-needs-for-SMEs/pi-governance-needs-SMEs.pdf. See methodology on pages 30–31.

- 28. Definition based on headcounts: micro: fewer than 10 employees, small: 10–49, and medium-sized: 50–250 employees.

- 29. ACCA, 2018. See page 6.