18

Technology and the Corporate Board 2020 and Beyond

Dr. Gary L. Evans

Professor, Corporate Governance and Strategy at the University of Prince Edward Island Faculty of Business

Introduction

This chapter looks at the impact that technology is having on and within the corporate boardroom today and looking forward to the future. Boardrooms have historically looked to technology as tools of efficiency and effectiveness, but today's technology is far more. It impacts the very fabric of the business model and requires that boards take a different view on the concepts of strategic planning and the business models that have historically impacted the profitability of the corporation. Directors need to go beyond the classic concepts of strategic planning and learn to apply exponential thinking as part of the decision process of the board when applying technology to their strategic planning. This chapter explores the mainstream technologies, and the fringe technologies of 2019–2020, that need to be part of the strategic planning process. Boards need to develop a different attitude toward technology not just as disruption but as essential to survival. Boards need to consider technology training for all board members so that they understand the concepts of upcoming and developing technologies as applied to their industry. The empirical evidence clearly indicates that the world is in an era of technological transformation, and radical changes will occur across industries. Each corporate board needs to improve at predicting how to best utilize technology to their advantage.

History

Boards have two primary functions: fiducial duty of care and future direction based on sound strategic planning processes. The fiducial aspect includes auditing and other governance committees and a copious review of historical records while maintaining a risk management decision-making process to protect the company assets and long-term profitability. Strategic planning looks at market penetration, expansion, and various aspects of the supply chain to allow for competitive advantage in new and existing markets. Boards meet regularly to review financial performance and the appropriate ratios and measurement as applied to their industry business model. Risk management policies and decision-making processes are aligned to ensure that the company maintains and develops best practice methodologies that allow them to provide confidence to shareholders. Comprehensive governance training provides board members clarity on their directorship duties and establishes knowledge of both the industry and business model in which the corporation competes. By adhering to good governance models and state-of-the-art best practices, boards can successfully direct the affairs of the corporation.

These concepts allow companies to enjoy profitable business success and continue to be critical going forward. However, today's corporations need to add an additional level of board technical competence that was not necessary in previous times (Turel, Liu, & Bart, 2019; Valentine, 2014). The technology era is not new; after all, the Internet celebrated its thirtieth birthday this year. Some companies falsely assume that they have a level of comfort with technological change and just need to have the right CIO and upgrade their systems to ensure state-of-the-art technologies. Unfortunately, this is not good enough to allow companies to maintain a sustainable future.

Directors need to understand existing technology and the fringe technologies and how they impact all levels of their organization. During the 1980s and 1990s, many companies looked to outsourcing as a method of staying current with technologies, trusting other companies to run the internal systems and to provide the technology for future development. The argument put forward was that this allowed businesses to focus on their core activities and not be hindered by system technology issues. This might provide short-term benefits for companies, but in the long term they lose control of the company direction. The systems department has become the change management division implementing new financial and integrated supply chain and global resource management systems, automating everything from manufacturing to consumer support systems. Companies developed new systems with protective firewalls and backup methodologies thereby protecting their data and business operations. This appeared good enough in the 1990s and early 2000s, but it will not suffice for the world of 2019 and moving forward to the 2020s.

Concerned by the many misinterpretations of his inaugural 1997 work on disruptive innovation, Christensen and three coauthors restated the core principals of disruptive innovation so that future researchers and practitioners of strategic planning would be better able to understand the phenomenon of disruption and the practical and academic application of the disruptive innovation theory (Christensen, McDonald, Altman, & Palmer, 2018). Christensen's theory has over 20 years of application, and directors are encouraged to explore the disruptive innovation theory in more detail. For this chapter, it is important to understand Christensen's definition of disruptive innovation. He classifies two types of potential disruption. The first is when incumbent companies ignore the low-end market, and companies use this as an opportunity to enter the market from below, often offering a lower-level product at a reduced cost. The second is the creation of new markets where none existed before. Uber is often used as an example of what is not disruptive innovation. Uber is a different business model attacking an already existing taxi market. A better example would be the creation of wearable technologies (Christensen, 1997; Christensen, 2015; Christensen et al., 2018). The fact that many technologies have exponential development curves makes the speed of deployment and adoption more critical. Technology disruption is speeding up, and the alarm bells are ringing from academics, professional firms, and governance institutions that board members need to become more engaged in technological changes and start developing board members for the future (Drejer, 2018; Evans, 2017; ICD, 2019; NACD, 2018; Turel et al., 2019).

Boards need to look to the future, not with linear thinking but by applying exponential thinking to the strategic planning and decision-making processes within the boardroom that are designed to handle disruption. Today's leaders have a two-step process, first to think exponentially and second to be comfortable with mainstream technologies while tracking the fringe technologies for upcoming change.

Exponential Thinking

Decision makers are comfortable with concepts of linear decision-making and incremental change, directors understand that organizations need to have constant change, and by taking incremental steps, companies can adapt and change with the environment. Planning cycles for both tactical and strategic planning are based on these concepts of structured linear and incremental change. Strategic planners need to move to the concept of exponential thinking in the fast-changing technology world of today (Raymond, 2014). Once a technology is accepted, people tend to forget how fast it advanced. Today, individuals accept smartphones as devices that act as a high definition camera, personal assistant, messaging device, navigation system, social media, and gaming device to name a few of the features far beyond the concept of a cell phone.

The journey of the smartphone will continue to evolve exponentially as fringe technologies become mainstream. An example of a research planning process that was initially started with linear thinking but then moved to exponential thinking was the study of DNA. It was initially thought that the human DNA string would be understood in 15 years. After five years, it was deemed that the project was failing and that it would take another 20 years to fully understand human DNA. Five years later, the full human DNA sequence was published (Funk, 2013; Raymond, 2014).

What the initial planners did not account for was that knowledge was doubling each year and that each next step was applying the previously gained knowledge. The same is true of technology today; it is not just proceeding one step at a time but doubling its knowledge year after year. Gordon Moore, the cofounder of Intel, predicted that transistors on a computer chip would double every year, and he was correct. Futurist Ray Kurzweil stated that this could be applied to certain technologies, but others would expand faster than this as they used existing technologies to create the next generation. This accelerated technology is sometimes referred to as Metcalfe's law, which was initially linked to the fast expansion of the network based on nodes (Lund & Safouhi, 2019; Raymond, 2014).

“Despite the fact that many technologies follow a predictable exponential growth rate, due to our lack of exponential intuition, we often have the impression that technology appears unexpectedly” (Lund & Safouhi, 2019, p. 1). “Invariably people create technologies and business plans as if the world is never going to change” (Raymond, 2014, p. 64).

Boardrooms need to take on exponential thinking when addressing current technologies. It is not enough to just address the technology that exists today; we need to consider how it will change in the future. Kodak employed the inventor of the digital camera on its staff but failed to see or embrace the technology because they were heavily invested in film technology and could not envision that the low-level quality of the initial digital camera was on an exponential change curve. Kodak's linear thinking not only made them miss the opportunity to be the industry leader but led to their bankruptcy in 2012. Failure to develop leadership direction that understands exponential thinking can jeopardize corporate long-term survival (Diamandis & Kotler, 2016; Lund & Safouhi, 2019).

It is clearly documented that one of the big concerns of every board is cybersecurity, but to treat it as today's problem with today's technology is a formula for failure. This approach will be forever chasing the rabbit and never catching it, only to be surprised by the next breach of security. This is not to say that short-term action is not necessary, but the ultimate solution needs to take a long-term view. The Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, and AI are all component parts of cybersecurity, and the board needs to develop an awareness of how the different technologies can work together to form secure platforms. Security is not a one-time fix but a process embedded within the company risk management methodology. The historical process of strategic planning defined “tactical” as 12–24 months and “strategic” as 2–5 years with a 5–10-year vision. Now, even if they have been keeping a close watch over technology, companies must consider that their industry is likely to face a system-level disruption every 10 years. Figure 18.1 provides planners a new strategic time horizon. For companies that are not tracking the changes in technology, change might appear without warning, creating a devastating business disruption. As more company boards prepare for the disruption phenomenon, few have the skillsets necessary to properly analyze the current trends and how they might impact their specific industry (NACD, 2016, 2018; ICD, 2019).

FIGURE 18.1 New Strategic Time Horizon

Source: The Future Today Institute, 2019, p. 18.

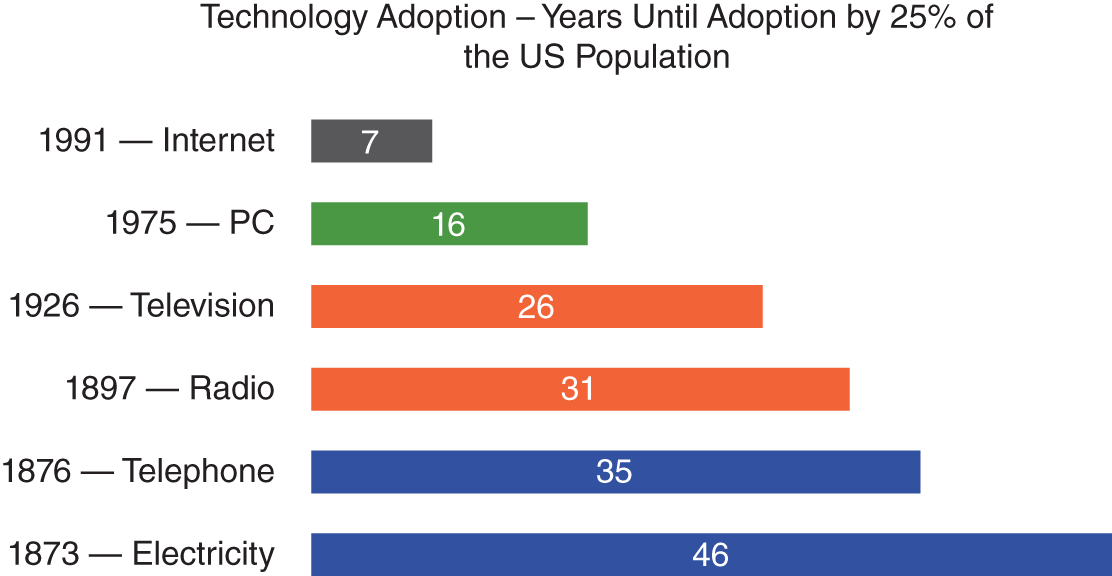

As a starting point for disruption, companies can look at history and grasp what they can from what has happened over the last 40 years without assuming the same time frames for adoption of technologies as in the past. Figure 18.2 highlights how time frames for adoption of new technologies have drastically changed over the years. Whether you follow Moore's law or Metcalfe's law, the fact is that the time frame for adoption is getting shorter.

Organizations need to study not only the technologies that are on the forefront but also those that appear on the fringe and how they can impact every part of the supply chain and relationships between suppliers and customers. Evans (2017) points out that disruptive innovation and its links to technologies go back to Schumpeter's (1942) published paper on “Creative Destruction,” which predated Christensen's disruptive innovation theory. All these theories offer today's corporate leaders the opportunity to explore how to think about disruption within their particular industry and how to react to the ongoing wave of change. While academics might debate and continue to test various aspects of different theories, practitioners need to embrace new theories and knowledge to help them better understand the change in thinking and decision-making for the current era (Hopp, Antona, Kaminski, & Salge, 2018). Today's market disruption is less likely to occur from a single technology than from the synchronization of different technologies, processes, and actions that lead to a new service or product (Petzold, Landinez, & Baaken, 2019).

Boards need to rethink how they consider time and innovation. Boards cannot just investigate the blatant technologies that impact their business today; they need to consider how a combination of technologies could impact any and all parts of their organization. Historically, we have tried to measure each separate technology exponentially one at a time, but the convergence of technologies will lead to greater market changes than just one technology. The convergence of AI, robotics, 3D/4D/5D printing, and nanotechnology will have a profound impact on industries ranging from autonomous vehicles to medical equipment (Kaplan, 2017; Lund & Safouhi, 2019).

FIGURE 18.2 Time Frames for Adoption of New Technologies

Source:Singularity.com and The Economist, https://info.aiim.org/aiim-blog/surviving-disruption-strategies-for-the-era-of-ai-and-machine-learning.

As boards spend time educating their members on strategic planning processes and financial literacy, they now need to consider training sessions that explore exponential thinking processes and technology assessment. This type of thinking will allow boards to consider how the synchronization of processes and technology will create new markets, products, and services. Boards will gain greater insights into technological change by linking with the academic and research communities. Boards need to follow the latest theories and debates on emerging technologies and decision-making processes. Tech-savvy boards are more likely to identify opportunities and timing that allows them not only to survive the disruption but to thrive (Nueno, 2016; Leatherberry, MaCormack, Kark, & Lamm, 2019). In reviewing future thinking and boards, Botha and Pretorius (2017) found board members lacked the basic skillsets for future thinking and encouraged board members to work with educational institutions familiar with the technologies and to develop a future-thinking training program. Surprisingly, board members over 60 were more adapted to future thinking than the younger board members. The board members that found future thinking most difficult were aged between 30 and 60 (Botha & Pretorius, 2017). A key element for boards to convert to exponential and future ways of thinking is their ability to adapt. Dysfunctional boards or boards that have structural issues need to resolve these first. For boards to adapt to new philosophies, they need strong leadership and sound governance structures (Leblanc, 2016).

Emerging Technologies

The first challenge for some boards is identification of the emerging technologies. One method is to use big data and patents to identify the technologies that demonstrate exponential growth (Segev, Jung, & Jung, 2013; Prokhorenko & Panifov, 2018). While this is plausible to identify the high-level emerging singular technologies, it does not address the convergence of technologies, and boards should be careful in their attempts to forecast future development that does not take into consideration fringe technologies. Farmer and Lafond (2016) proposed that in using Moore's law and combining it with historical cost data, it is practical to use big data to forecast technological progress. Using this philosophy, their model attempts to forecast the potential market size solar technology will have in the energy sector. The model forecasted that solar energy could capture 20 percent of the market by 2027 (Farmer & Lafond, 2016). Other tools available to the board include reports put out by different organizations that watch and track technology trends and performance.

Both the Gartner Group and Future Today Institute (FTI) provide annual updates on what they see as the leading technologies to watch and those to be mindful of that currently are considered on the fringes. Both Gartner and FTI indicate that AI, blockchain, and IoT are technologies that will have substantial impact on businesses and their business models in the near future and that these technologies are necessary for the corporate strategic planning process. Boards need to consider how technology will change their industry and the impact it will have on the economic business model (Jari & Lauraeus, 2019; Olson, Remick, & Tapia, 2016). New industries will be created with technology, and some will radically change. Technology impacts the core business of every corporation. Technology is now and will forever be a responsibility of the board. The King IV report has declared that technology is part of the corporate DNA and should now have a permanent position on the board agenda (King IV Report, 2016).

Volatility, uncertainly, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) were first put forward in 1987 by the leadership theories of Bennis and Nanus to deal with a changing world. This was later refined by Krupp and Schoemaker, who proposed six disciplines of leadership and management drawn in a loop of learn, anticipate, challenge, interpret, decide, and align (Jari & Lauraeus, 2019). These theories can be used as tools to help boards understand and respond to technological impact. The Gartner group uses what they refer to as the “hype cycle.” Figure 18.3 demonstrates where Gartner 2019 sees technologies within a 10-year time frame. Their hype cycle might appear similar to what project managers use as project learning or change curves where the excitement of new methods generates high expectations in the beginning, but as the change process starts, users get disillusioned during the process of managing the change.

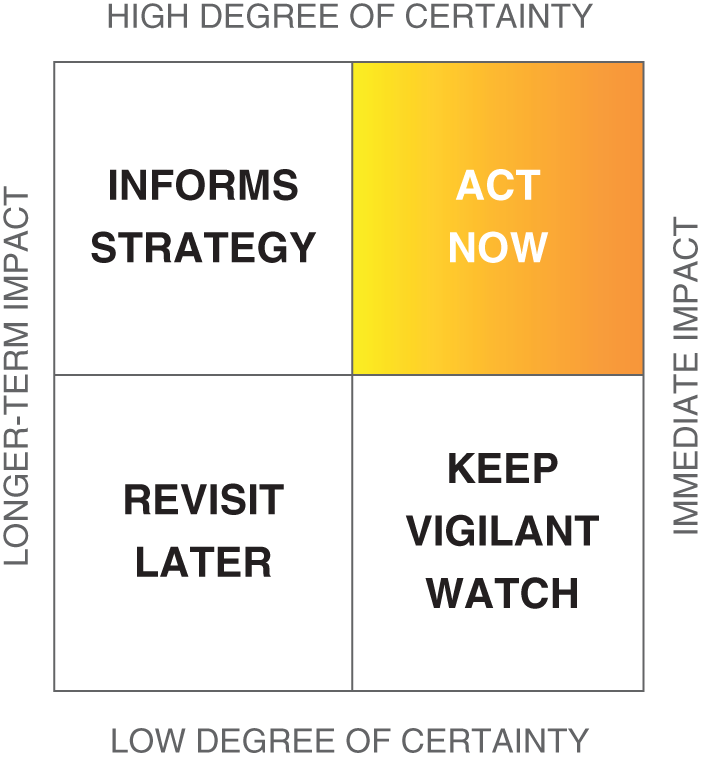

While the graph is easy to comprehend, it is high level, and those who consider using this as an indicator will need to develop a much deeper understanding of the technologies to best understand the ramifications of the technology on their specific business environment. Many of the technologies put forth in the model are in themselves hybrids of different levels of technology that could incorporate various levels of AI, blockchain, IoT, cloud computing, big data, and so on. FTI took a different approach, listing 315 different technologies and their impact by industry. FTI offers a four-quadrant model, outlined in Figure 18.4, of “Revisit, Inform, Act, or Watch,” allowing users to utilize different responses depending on the technology and how it may or may not impact their industry. Both reports provide suggested insights and a watchlist for what might come next, including the technology companies best positioned to move the technology forward (Future Today Institute (FTI), 2019; Gartner, 2019).

FIGURE 18.3 Where Gartner Sees Technologies Within a 10-Year Time Frame

Source: Gartner, Hype Cycle 2019.

FIGURE 18.4 Four-Quadrant “Revisit, Inform, Act, or Watch”

Source: Future Today Institute, 2019, p. 16.

Certain technologies are likely to impact all companies during the next 2–5 years and therefore are considered requirements for all strategic planning. The technologies identified as having the biggest impact of change in today's planning cycle are AI, blockchain, and IoT. Being tech-savvy is now a critical requirement for boards. It is no longer a question of whether disruption will occur; it is a question of when (Leatherberry et al., 2019).

Artificial Intelligence

The concept of AI goes back to the report by Turing (1950) when he created the first concept of how to measure AI. The measurement concept of the Turing test was if you could not tell whether it was a human or a computer that had passed the Turing test. This became more sophisticated, measuring different levels of AI from low-level AI with human intervention for each decision point and high-level AI that did not need to inform the human and could make all decisions without human intervention. Today, most AI would be classified as low- to medium-level in which the system has limited decision-making capabilities based on mathematical algorithms. Many electronic systems in homes are low-level AI for which we set the initial decision, but future decisions are automatic. The temperature in your house does not ask you to turn on the furnace; it happens automatically based on how a human set the thermostat. More sophisticated AI systems react to a broader range of decision points such as what is found in electronic trading systems.

On February 5, 2018, an electronic trading system plunged the Dow Jones by 800 points in 10 minutes. While for the most part we have had positive experiences with AI, it is a relatively new technology, and errors will happen. Stock brokers are expensive; humans and computers using big data are more efficient at seeing patterns in rapid trading, so it not surprising that this has become an attractive area for automation. AI technology is improving quickly, and as it improves, companies will be more reliant on AI to be a key part of cybersecurity. AI has made substantial gains in recent years and is positioned to be a major disruptor during the next 2–5 years (Kaplan, 2017). Evans (2017) proposed that one of the major improvements in AI development has been the change in approach to AI development. System developers are using fuzzy logic and probabilistic methodologies to allow systems to learn on their own. A machine learning algorithm could be used to select the next board member based on a set of attributes and desired outcomes. This concept was recently studied showing that while improvements need to be developed on some current shortcomings of algorithm development, director selection analysis may be completed in part by an AI system in the not too distant future. (Erel, Stern, Tan, Weisbach, 2019)

It is not realistic to assume that AI will have self-awareness or mimic human consciousness in the foreseeable future, but it is realistic to expect AI to replace most mundane positions that involve repetitive decision-making processes. AI technology already is superior to humans in identifying patterns from big data and will be a major tool for future decision-making. Training and educating board members on AI technology and how it relates to the other mainstream and fringe technologies will be an essential part of training directors (Lancefield & Gagliardi, 2016; Lauterbach & Bonime-Blanc, 2016). The push to develop autonomous cars and to have the ability to mine data lakes has been an accelerator in AI research. The next generation of technologies including blockchain and IoT need AI to make them more effective. Board members will not need to understand the nuts and bolts of AI, but they do require an understanding of AI's current capacity and the research developments underway. AI technology's biggest disruption is what it can do when married to other technologies.

Blockchain

For uninformed individuals, blockchain might appear as a complex, difficult to understand technology with limited applicability within current business models. The potential for this technology is far reaching, and while Gartner (2019) has it listed as 5–10 years, Webb, Giralt, Palatucci, and Perez (2019) classify it as “act now.” Born from Bitcoin, blockchain technology has three basic characteristics: decentralized, immutable, and transparent. Blockchain is designed with a validation process making it difficult to tamper with the technology; an organization would need to control over 50 percent of the decentralized system to hack it. Once input, the data cannot be tampered with and provides a complete audit trail of all transactions.

The root of blockchain was Bitcoin, and cryptographic validation is a core component of the technology. Combine blockchain technology with IoT and AI, and the possibilities of the impact this technology could have on the supply chain are staggering. A misconception of blockchain is that it will do away with traditional banking and that its primary purpose will be in the financial sector. Blockchain will impact all sectors, and while applications are currently limited, this is likely to change exponentially over the next couple of years. The impact that blockchain will have on financial institutions will depend on the evolution of defining the value of the banking business model. As Figure 18.5 demonstrates, all parts of the supply chain will be impacted by blockchain technology (Casey & Vigna, 2018; Casino, Dasaklis, & Patsakis, 2019; Caytas, 2016; Evans, 2017; Min, 2019; Morkumas, Paschen, & Boon, 2019; Poszler, Ritter, & Welpe, 2019). Blockchain technology will be a critical element as the IoT takes hold across industries. Understanding blockchain will provide directors with an important insight into the development of current and future business models for their prospective businesses. Blockchain will bring a new level of diligence to board governance and needs to be understood by the board (Davidson, De Filippi, & Potts, 2016).

Cloud

Cloud technology is being adopted by consumers and industry at a rate that highlights the close link between business models and technological disruption. No single type of consumer or industry has taken a leading role. Cloud technology growth has a positive correlation relationship between companies with a focus on cost reduction (Loukis, 2019). Cloud technology is an example of where the technology is disrupting the disruptors. The war is on for who will dominate this new market, and the range of potential services is expanding as the major players merge and look into how cloud technology can interface with other mainstream technologies from blockchain to AI. Amazon took the advantage of cloud technology with a new business model creating a revenue stream from what was a cost center (DaSilva, Trkman, Desouza, & Lindic, 2013). IBM's acquisition of Red Hat in 2018, valued at 34 billion USD, demonstrates the importance of this new market segment to the major cloud providers. While some reluctance existed initially due to concerns about security, improved encryption methodologies and adoption of new data protection technologies remove the concerns about cloud technology security (Alghamdi et al., 2019; Ratten, 2015). In terms of visionaries, during a breakfast meeting 20 years ago, Bill Gates explained the concepts of what he then termed the “neural network” and how it would change the whole concept of data storage. This would become known today as cloud technology. Bill Gates has long since retired from Microsoft, but his concepts of exponential thinking and visioning obviously continue within the company, as Microsoft is a top provider of cloud technology. Cloud technology can be utilized by virtually every company. The question directors need to consider is how it will be used and the potential advantages it can bring to a revised business model. Cloud technology is now mainstream, and companies need to consider not just the services it provides today but additional functionality, new products, and services of the future. Some companies will redevelop their business models to take advantage of cloud technology, and others will fail and no longer be in business (DaSilva et al., 2013).

FIGURE 18.5 Parts of Supply Chain Impacted by Blockchain Technology

Source: Casino, F., Dasaklis, T., Patsakis, C. (2019), p. 62.

5G

5G is a technology that most corporate leaders do not fully understand in terms of its potential impact. Not only does it compete with the high speed of fibre optics; it is wireless and easier to deploy than all other forms of wi-fi. It has the potential of 100 times current speeds and capacity with reduced power consumption. While some see deployment taking 2–5 years, it has the potential to create new products, services, and connectivity with the IoT that have not yet been envisioned. Combining its improved response time, it brings concepts of the smart home, smart city, and supply chain disruption to a new level. This is a technology that is underestimated by many, and when combined with other technologies, it unblocks some of the hurdles that have been restricting new developments (Abbosh & Downes, 2019). This is a fringe technology that unlocks many other technologies from their limitations and should be watched closely for industry disruption. Abbosh and Downes (2019) use this technology as an example to highlight companies' failure to understand the magnitude of change because they are stuck in the process of linear thinking. Gartner did not include 5G on their 2018 (Figure 18.3) emerging market technology hype cycle curve. It was included as informing strategy by Webb et al. (2019) with the prediction that it will reduce transmission latency from 30 milliseconds to less than 1 millisecond. 5G will unleash the power of cloud robotics and create a new wave of industrial robotics (Abbosh & Downes, 2019; Webb et al., 2019). Directors need to discuss technologies from an informed level of understanding. They do not need to be engineers or systems people, but just as all directors should be able to read and understand financial statements, directors in 2019 and beyond need to understand both the mainstream and fringe technologies with an exponential mindset.

Internet of Things

Companies can expect explosive growth in the IoT, and we have only begun to see the potential opportunities for new products and services. With AI, blockchain, and 5G coming to market, this opens a host of new opportunities for the IoT. Without the above three technologies, it would be difficult to bring the IoT to the forefront. These technologies are essential for both response and coverage. With the development of these technologies, it has become possible to release the power of the IoT (Valtanen, Backman, & Yrjola, 2019). The smart city, home, office, warehouse, and manufacturing reaches new levels of automation. Standalone systems that worked autonomously with each other can now communicate and share, allowing a new level of robotics and technology sharing. It is feasible to consider markets and services that will cross many industries. A major concern for the expansion of the IoT is cybersecurity, as the IoT opens new entry points across multiple systems (Radanliev et al., 2019). Cybersecurity is a critical element for the expansion of the IoT, and this risk can be mitigated by interfacing with other technologies such as AI and blockchain. The benefit of the IoT, as with many technologies, is in the adoption of new business models (Metallo, Agrifoglio, Schiavone, & Mueller, 2018).

Quantum Computing

This would currently be classified as a weak signal, as currently there are less than a dozen true quantum computers in the world with extremely difficult environmental constraints. They can be compared to the first IBM mainframe when the world was still trying to figure out how to use them, and special buildings and structures had to be created to house them. That is quantum computing today. New chip designs are being explored, and ultimately the coolant technology will need to be addressed for mass production to be feasible. The power that would be unleashed by this level of technology would be like comparing today's technology to what existed in the 1940s. Board directors may not concern themselves with this today but in ten years this could move from very outside fringe to mainstream.

Cybercrime

One of the exponentially growing areas is cybercrime research from the NACD, ICD, and IOD. All these corporate governance institutes have identified cybercrime as a growing concern for directors, and while the awareness is most certainly a discussed topic on all boards, a NACD study showed that board members' confidence that they were prepared for a cyberattack dropped from 42 to 37 percent from 2016 to 2017; 2019 Reports from the ICD and IOD echo similar concerns. The recent municipal attacks on infrastructure will continue to erode board members' confidence in cybersecurity (Atkins & Kashyap, 2019). The sophistication of cybercrime has grown far beyond phishing scams to include municipalities and major companies being held for ransom. The city of Baltimore has had its whole city infrastructure held up for ransom, and at the time of writing this chapter, the city has not been able to rectify large elements of their resource management system. The simple task of paying for parking tickets is no longer possible, and individuals need to line up to pay in person for many services that historically had been handled online. A study by the University of Calgary identified that not only is cybercrime expanding exponentially, but governments and businesses at all levels are not adequately trained or prepared to deal with the increased level of crime (Pesic, 2018). This report highlights the increased risk for the IoT and smart cities and acknowledges that both government and businesses need to develop new ways of thinking about cybercrime. The study put forward as a potential solution tax incentive to encourage and reward SME to develop a level playing field against those focused on committing cybercrime (Pesic, 2018). This author believes that neither government nor the private sector are properly trained or positioned for this approach to work. An alternative could be expansion of research funds to encourage the technology firms to work with universities to develop new solutions. Country legislation based on current technologies will do little to curb cybercrime that is international in scope and ability. Cybercrime, as with climate change, will require an international approach and exponential thinking to resolve this effectively (Lund & Safouhi, 2019).

The corporate governance associations have put forward several templates to aid board members on cyberrisk oversight (Clinton, 2017). Boards need to continue to review their risk management portfolios, what they are protecting, how they are doing it, and the most likely forms of attacks they might face (NACD, 2018; Edwards, 2019; ICD, 2019; IoD, 2019). As the IoT continues to grow, the opportunity for attacks grows. It is estimated that attacks in 2019 will have a 2 trillion USD price tag, which represents a quadruple of cost since 2015 (Atkins & Kashyap, 2019).

The “big four” professional accounting firms (Deloitte, PWC, KPMG, and E&Y) all have increased the importance of cyber-risk management, highlighting that technology is not just defensive but must include a combination of defensive and offensive technology to thwart cyberattacks. All the firms are offering their clients strategic models that take cybercrime into consideration. The starting point for boards is a candid review of how tech-savvy the board is and at which level is necessary to mitigate risk to the company both in protection and utilization of technology as an enabler for the future.

Finally, companies today need to ensure that they are compliant with evolving international laws, or they might find themselves guilty of a cybercrime. In May 2018, the EU implemented the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and fines can range from thousands to millions of euros. Google was fined 50 million euros in January 2019 by the French Data Protection authority for violations of the GDPR. Other companies have had fines in the thousands, and the top 500 U.S. companies have paid over 7 billion USD to achieve compliance. In the global economy, companies offer products and services to a global market on the Internet, and this creates new levels of responsibility for all companies. If you are a North American company doing business in the EU, this requires the Internet platform to be GDPR compliant. Substantial criticism has been made by legal professionals and technology companies on the GDPR, but this is the law, and regardless of a particular view or criticism, compliance is necessary. Data protection laws are likely to be expanded, and while some form of harmonization might be desirable, it is not likely to occur during the short term (Dimov, 2019). Companies need to protect themselves and at the same time adhere to expanding regulatory requirements. Fragmentation of regulations might create regionally different aspects of the Internet and ultimately have the impact of slowing down new technology development.

Other Technologies

The technologies outlined above are just a few of the disruptive technologies under development. Webb et al. (2019) listed over 300 different technologies capable of disrupting existing business models. Many of these technologies only become disruptive when combined with other technologies. It is the merging of different technologies that creates new markets and changes existing business models. Some of the additional technologies that are deemed important in terms of their applicability to disruption include big data, virtual reality, augmented reality, drones, deep learning, robotics, robotics process automation (RPC), robotics desktop automation (RDA), and BOTs. Evans (2017) outlines the importance of a broad range of technologies to the decision-making process of the board. Padayachee, Matthee & der Merwe (2017) conclude that the technologies are designed to be enablers. The biggest challenge for companies is not the technology but the culture, mindset, old methods, and willingness to embrace change.

For board directors struggling with where to start with the vastness of the potential of disruptive technologies, look at the developments and movements of the “big nine” technology companies. The six based in the United States are the G-MAFIA: Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, IBM, and Apple. The three in China are BAT: Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent. Other niche technology companies exist with well-known products such as Huawei, Cisco, and Twitter, to name a few, but the big nine dominate the landscape and are likely to be at the forefront of disruption (Galloway, 2018; Webb, 2019).

Business Models and Disruptive Technology

It is well documented that disruptive technologies change existing business models or create new markets that require new business models (Cozzolino, Verona, & Rothaermel, 2018). Directors need to identify whether the disruption can allow modification of existing business models or, alternatively, a new model is required that does not carry the bias and restrictions of the old model. The strategic planning process of the past does not facilitate the new ways of thinking that are necessary to allow companies to effectively address the core components that disruption is having on existing business models. Much of the strategic planning process utilized today does not allow the adaptive thinking required to handle the reality of disruptive technology (Drejer, 2018). A review of the current literature on disruptive business model development and adaptation has identified numerous research gaps in processes and methodologies on both a theoretical and practical level. For example, looking at the innovation of a new business model to deliver competitive advantage, yet maintaining industry assumptions that in themselves might no longer be true, result in a flawed model. Changing a model without the appropriate support mechanism brings a host of other problems in implementation. Similar issues exist with adaptive models, and often the overlaps of models are not clearly understood (Hopp et al., 2018; Schiavi & Behr, 2018). The confusion between legacy models and new models, whether to have a defensive or offensive approach, and selecting the wrong strategy or wrong alliance inadvertently create a new level of competition (Bughin & Zeebroeck, 2017).

Conclusion

The next level of technology disruption is positioned to explode as barriers of development are removed. The advances of cloud technology, AI, blockchain, and 5G will drive the next level of changes exponentially. The IoT will move forward, creating new markets and opportunities, but for some industries, the supply chain models of the past will be completely dismantled. Business models will undergo radical change, and future thinking is no longer a nice-to-have attribute; it will be essential for survival. Board members need to be prepared to think exponentially and develop future thinking as a measurable attribute for all board members. The path will not be easy, and the first question that needs to be asked is, are they ready to change?

There are some steps that boards can take to help prepare their members for new ways of thinking and performing. First, boards need to build their confidence in the latest technologies and educate their members on the technologies that are most likely to impact their industry (Olson et al., 2016; Valentine, 2014; Valentine, De Haes, & Timbrell, 2016; Valentine & Stewart, 2013; Weill & Woerner, 2016). This might require external as well as internal resources. Second, board members should study the big nine technology companies to get a sense of what they are investing in and investigate how they approach exponential thinking (Webb, 2019). When possible, boards should consider training in exponential and future thinking for board members. Boards should act immediately to determine if their current strategic plan has encompassed exponential and future thinking (Olson et al., 2016; Vasarhelyi, 2013). The process of preparing the board for the future needs to be a priority for every board. Board leadership needs to prepare directors to become tech-savvy, incorporating new processes for strategic planning that includes exponential and future thinking. Failure to do so will jeopardize not only the health of the organization but its survival.

About the Author

Gary L. Evans, Dip. CS, BA, Hons. B. Comm, MBA, PhD, prior to embarking on an academic career, was senior partner and CEO for KPMG Consulting for Central Eastern Europe and prior to that appointment was Partner in Charge of Chemicals, Pharmaceuticals and Energy for the London, UK, office of KPMG for tax, audit, and consulting. As a partner in a professional firm Dr. Evans spent a substantial amount of time with corporate boards and the executive management of major international corporations.

After retiring from professional practice Dr. Evans has dedicated his time to research and teaching at the University of Prince Edward Island and completed his PhD in Corporate Governance at Liverpool John Moores University. Dr. Evans continues researching corporate boards globally and is on the editorial board of three academic journals, has been the guest editor for special corporate governance journal publications, and is considered a leading author within the field of corporate governance. Dr. Evans developed the Board Culture Theory using CGT. An active international speaker, he has given presentations on technology, diversity, and other key governance issues across Europe. Dr. Evans is an active member of the indigenous community and holds dual British/Canadian citizenship.

References

- Abbosh, O., Downes, L. (2019). 5 G's potential, and why businesses should start preparing for it. Harvard Business Review, March 5, 2019, 1–5.

- Alghamdi, B., Elnamaky, M., Arafah, M., Alsabaan, M., & Bakry, S. (2019). A context establishment framework for cloud computing information security risk management based on the STOPE view. International Journal of Network Security, 21(1), 166–176.

- Atkins, B., & Kashyap, R. (2019). What corporate boards still don't understand about cyber risk, Quartz at Work, 1–5, https://qz.com/work/1632903/what-corporate-boards-still-dont-understand-about-cyber-risk/.

- Botha, A. P., & Pretorius, M. W. (2017). Future thinking: The scarce management skill. Technology Management for Interconnected World. Proceedings of PICMET 2017, 1–10.

- Bughin, J., & Zeebroeck, N. (2017). 6 digital strategies, and why some work better than others. Harvard Business Review, July 31, 2017, 1–5.

- Casey, M. J., & Vigna, P. (Apr. 9, 2018). “In blockchain we trust.” MIT Technology Review. Retrieved on Mar. 13, 2019, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/610781/inblockchain-we-trust/.

- Casino, F., Dasaklis, T., & Patsakis, C. (2019). A systematic literature review of blockchain-based applications: Current status, classification and open issues. Telematics and Informatics (36), 55–81.

- Caytas, J. D. (2016). Developing blockchain real-time clearing and settlement in the EU, US, and globally. Columbia Journal of European Law: Preliminary Reference. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2807675.

- Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator's dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Christensen, C. M. (2015). Disruptive innovation is a strategy, not just the technology. Business Today, 4 Jan. 2015, Interview, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A394465959/ITOF?u=otta0998&sid=ITOF&xid=b86b4559. Accessed 4 June 2019.

- Christensen, C. M., McDonald, R., Altman, E. J., & Palmer, J. E. (2018). Disruptive innovation: An intellectual history and directions for future research. Journal of Management Studies, 55(7), 1043–1078.

- Clinton, L. (2017). Cyber Security Oversight Handbook, (NACD) National Association of Corporate Directors, Handbook Series, 1–42.

- Cozzolino, A., Verona, G., & Rothaermel, F. (2018). Unpacking the disruption process: New technology business models, and incumbent adaptation. Journal of Management Studies, 55(7), 1166–1292.

- Davidson, S., De Filippi, P., & Potts, J. (2016). Disrupting governance: The new institutional economics of distributed ledger technology. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2811995.

- DaSilva, C. M., Trkman, P., Desouza, K., & Lindic, J. (2013). Disruptive technologies: A business model perspective on cloud computing. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 25(10), 1161–1173.

- Diamandis, P., & Kotler, S. (2016). Goodbye linear thinking: Hello exponential! Rotman magazine, 39–43. Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto.

- Dimov, D. (2019). Five common myths about the GDPR, Techopedia, June 7, 2019, https://www.techopedia.com/5-common-myths-about-the-gdpr/2/33840?utm_campaign=newsletter&utm_medium=best&utm_source=06122019&utm_campaign=Techopedia&utm_content=Job+Role%3A+Ethical+Hacker&utm_medium=email&utm_source=janalta.

- Drejer, A. (2018). Disruption and strategic management: What are the theoretical implications of disruption on strategy? Journal on Business Review, 5(3), 1–10, https://dol.org/10.6176/2010-4804_5.3_111.

- Edwards, B. P. (2019). Cybersecurity Oversight Liability, Georgia State University Law Review, 35(3), 662–677. Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol35/iss3/3.

- Erel, I., Stern, L. H., Tan, C., & Weisbach, M. S. (2019). Selecting directors using machine learning, Charles A. Dice Center for Research in Financial Economics, Ohio State University, Fisher College of Business, WP 2018-05, 1–53, http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3144080.

- Evans, G. (2017). Disruptive technology and the board: The tip of the iceberg. Economic and Business Review, 3(17), 205–223.

- Farmer, J. D., & Lafond, F. (2016). How predictable is technology progress? Research Policy, 45, 647–665.

- Funk, J. L. (2013). What drives exponential improvements. California Management Review, University of California Berkeley, 55(3), 134–152.

- Future Today Institute (2019). The Future Today Institute (FTI) helps leaders and their organizations prepare for deep uncertainty and complex futures. Retrieved from https://futuretodayinstitute.com/.

- Galloway, S. (2018). The Four: The Hidden DNA of Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google. New York: Portfolio/Penguin.

- Gartner (2019). Gartner Top 10 Strategic Technologies for 2018. Retrieved from https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/gartner-top-10-strategic-technology-trends-for-2018/.

- Hopp, C., Antona, D., Kaminski, J., & Salge T. O. (2018). What 40 years of research reveals about the difference between disruptive and radical innovation. Harvard Business Review, April 2019, pp. 2–5.

- ICD (2019). Emerging Technologies Understanding the Disruption Ahead: An Introduction for Corporate Directors, Institute of Corporate Directors Quebec Chapter, April 2019, 1–11.

- IoD (2019). Cyber Security for your Business, Institute of Directors (UK), https://www.iod.com/news-campaigns/cyber-security-for-your-business#tab-Blogs.

- Jari, K., & Lauraeus, T. (2019). Analysis of 2017 Gartner's three megatrends to thrive the disruptive business, technology trends 2008–2016, dynamic capabilities of VUCA and foresight leadership tools. Advances in Technology Innovation, 4(2), 105–115.

- Kaplan, J. (2017). Viewpoint artificial intelligence: Think again. Communications of the ACM, 60(1), 36–38.

- King IV Report. (2016). Institute of Directors in Southern Africa. The Institute of Directors in Southern Africa NPC, all rights reserved. WWW.iodsa.co.za.

- Lancefield, D., & Gagliardi, C. (2016). Reimagining the boardroom for an age of virtual reality and AI. Harvard Business Review, 2–4.

- Lauterbach, A., & Bonime-Blanc, A. (2016). Artificial intelligence: A strategic business and governance imperative. NACD Directorship, September/October, 54–57.

- Leatherberry, T., McCormack D., Kark, K., & Lamm, R. (2019). The tech-savvy board, engaging with CIOs and management on strategy, risk, and performance. Deloitte Insights, http://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/topics/leadership/cio-board 1–13.

- Leblanc, R. (2016). The Handbook of Board Governance: A Comprehensive Guide for Public, Private, and Not for Profit Board Members. Richard LeBlanc, ed., John Wiley & Sons.

- Loukis, E. (2019). Do strategy processes, personnel and technology affect firms' propensity to adopt cloud computing? An empirical investigation. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 6, 1–18.

- Lund, T., & Safouhi, H. (2019). Exponential life an analysis of exponential technologies, University of Alberta Libraries, https://doi.org/10.7939/R36H4D67F,1-29.

- Min, H. (2019). Blockchain technology for enhancing supply chain resilience. Business Horizons, 62, 35–45.

- Metallo, C., Agrifoglio, R., Schiavone, F., & Mueller, J. (2018). Understanding business model in the Internet of Things industry. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 136, 298–306.

- Morkumas, V., Paschen, J., & Boon, E. (2019). How blockchain technologies impact your business model. Business Horizons, 62(3), 295–306.

- NACD. (2016). Cyber-risk oversight: Director's handbook series. Washington, DC. USA: National Association of Corporate Directors. Retrieved from: https://www.nacdonline.org/cyber.

- NACD (2018) The Report of the NACD Blue Ribbon Commission on Adaptive Governance: Board Oversight of Disruptive Risks, Washington, DC. USA: National Association of Corporate Directors. Retrieved from: https://www.nacdonline.org/insights/publications.cfm?ItemNumber=61319.

- Nueno, P. (2016). The future of governance: 10 trends for the board of 2020. Harvard Business Review, Harvard Business School Publishing, June, 45–51.

- Olson, N., Remick, T., & Tapia, A. (2016). As global business transforms, boards must keep pace. The Corporate Board, November/December, 17–22.

- Padayachee, R., Matthee, M., & der Merwe, A.V. (2017). Disruptive Technologies and IT decision making in an agile business environment, IEEE Africon 2017 Proceedings, 843–848.

- Pesic, G. S. (2018). Surviving and thriving in the digital economy. The School of Public Policy Publications, SPP Briefing Paper, University of Calgary, http:dx.doi.org/10.11575/sppp.v11io.43356, 1–14.

- Petzold, N., Landinez, L., & Baaken T. (2019). Disruptive innovation from a process view: A systematic literature review. Creative Innovation Management, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., (28), 157–174.

- Poszler, F., Ritter, A., & Welpe, I. (2019). Blockchain startups in the logistics industry: The technology's potential to disrupt business models and supply chains.

- Prokhorenko, D., & Panifov, P. (2018). Discovery of technology trends from patent data on the basis of predictive analytics, IEEE 20th Conference on Business Informatics, 148–152.

- Radanliev, P., De Roure, D. C., Nurse, J., Burnap, P., Anthi, E., Ani, U., Maddox, L., Santos, O., & Montalvo, R. (2019). Cyber risk form IoT technologies in the supply chain discussion on supply chains decision support system for the digital economy. University of Oxford, 1–9.

- Ratten, V. (2015). Cloud computing technology innovation advances: A set of research propositions. International Journal of Cloud Applications and Computing, 5(1), 71–78.

- Raymond, C. (2014). The Exponential Mind: Renowned futurist Ray Kurzweil models a better way of thinking. Success, October 2014, 62–66.

- Sainio, L. M., & Puumalainen, K. (2007). Evaluating technology disruptiveness in a strategic corporate context: A case study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Science Direct, 74, 1315–1333.

- Schiavi, G. S., & Behr, A. (2018). Emerging technologies and new business models: a review on disruptive business models. Innovation and Management Review, 15(4), 338–355.

- Segev, A., Jung, C., & Jung, S. (2013). Analysis of technology trends based on big data. IEEE International Congress on Big Data, 65, 419–420.

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1942). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (2nd ed.). New York and London: Harper & Brothers.

- Turel, Liu, & Bart (2019). Board-level IT governance. What your company should know and how it should act. In IT Professional, 21(2), 58–65. 1 March–April 2019. doi: 10.1109/MITP.2019.2892937.

- Turing, A. (1950). Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind, 59(263), 433–460. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2551299.

- Valentine, E. (2014). Can your board deliver technology governance? The Corporate Board, Vanguard Publications, Inc. Okemos, MI. March/April, 6–9.

- Valentine, E. L., De Haes, & Timbrell, G. (2016). The board's role in the governance of enterprise information and technology. In The Handbook of Board Governance: A Comprehensive Guide for Public, Private, and Not-for-Profit Board Members. Editor: Richard LeBlanc, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 574–596.

- Valentine, E. L., & Stewart, G. (2013). The emerging role of the board of directors in enterprise business technology governance. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 10(4), 346–362.

- Valtanen, K., Backman, J., & Yrjola, S. (2019). Blockchain-powered value creation in the 5G and smart grid use cases. IEEE Access, 7, 25690–25706.

- Vasarhelyi, M. A. (2013). Formalization of standards, automation, robots, and IT governance. Journal of Information Systems, 27(1), 1–11.

- Webb, A., Giralt, E., Palatucci, M., & Perez, K. (2019). Tech trends report: Emerging science and technology trends that will influence business, government, education, media and society in the coming year. Future Today Institute, 12 Annual Edition, www.futuretodayinstitute.com.

- Webb, A. (2019). The big nine: How the tech titans and their thinking machines could warp humanity. New York: Public Affairs.

- Weill, P., & Woerner, S. L., (2016). Becoming better prepared for digital disruption, NACD Directorship, Washington, D.C. March/April 2016.