15

Board Oversight and Climate Change: What Directors Need to Know

Patricia A. Koval

Experienced Corporate Director and Former Senior Partner, Torys LLP (Retired)

Climate change, once viewed as just an environmental or sustainability issue, is now seen as a critical issue which may have material financial impacts on businesses and affect their long-term growth and profitability. Indeed, it is now “mainstream,” driving questions for businesses such as: What impact will climate change have on the company's operations in the short, medium, and long term? What impact will it have on the viability of the company's current business model? How can the company ensure that its business model is resilient in the longer term as climate change occurs and the world transitions to a lower-carbon economy? The World Economic Forum's 2019 Global Risk Report identified “extreme weather events” as the macroeconomic risk with the highest likelihood and third highest impact over the next ten years, and the failure of climate-change mitigation and adaptation as second in terms of both likelihood and impact.1

This chapter looks at why and how climate change is now a core business issue for companies, public or private, and suggests how it should be addressed within the board of directors' governance framework. It highlights important background and specific issues for boards, and suggests questions that directors should ask. Given that disclosure of climate change–related matters is a timely subject, particularly for public companies, the chapter also considers this issue.

Introduction

While some in Canada began to seriously look at climate change–related risk early in this century,2 the attention of the global business community focused on the 2015 Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework on Climate Change (UNFCCC). At the same time, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) identified the systemic risk posed by climate change to the stability of the global financial system. This was signaled in a keynote speech identifying climate change as the “tragedy of the horizon”3 given by Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England and then-chairman of the FSB.

Following those events, under the leadership of Governor Carney and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the FSB formed the industry-led Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). The TCFD released its final recommendations, made “by the market for the market,” in June 2017,4 together with an accompanying paper on implementation guidance and a technical paper on scenario analysis. The recommendations create a framework for climate change–related analysis and disclosure for companies. At their heart, the TCFD recommendations ask companies to identify, evaluate, and assess climate-related risks and opportunities in time horizons that stretch beyond the traditional business planning cycle, and, with that information, to evaluate their business models and strategies in order to ensure resilience to climate-related risks and, hence, long-term viability. Work continues on developing frameworks for implementation.5

Separately, Canada's provincial securities regulators, under the umbrella, Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA), surveyed the state of climate change–related disclosure in 2017 and found it wanting.6 In their April 2018 report, they affirmed that the legal requirement to disclose material risks includes material climate change–related risks and opportunities and material financial impacts on an issuer's business. As well, the CSA emphasized the importance of multi-period analysis, stating that if an issuer concludes that a climate change–related risk could reasonably be expected to have a potential material impact on the issuer at some time in the future, it should be disclosed even if it may arise only over the medium or long term.7 Importantly, the CSA highlighted climate-related governance, indicating that regulators would seek to introduce requirements for mandatory disclosure of a company's governance process in relation to material risks and opportunities, including the board's responsibility for oversight and the role played by management, as well as disclosure of how the company oversees the identification, assessment, and management of material risks.8

More recently, the federally appointed Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance was asked to examine the conditions necessary to create a market for sustainable finance in Canada. In its Final Report, published in June 2019, it emphasized corporate governance and included extensive recommendations for corporate disclosure relating to climate change in Canada.9

For well over ten years, various corporate stakeholders, including asset managers, pension funds, lenders, insurers, and some consumers, have sought enhanced board scrutiny and management of climate change–related risks.10 There are now numerous initiatives by investors, banks, and insurers to create guidelines, investment screens, processes, and models to incorporate climate-related information, including climate governance, into their decision-making and stress-testing of their portfolios.11 Not surprisingly, there is also an established and growing climate change–related service industry—collecting and providing climate data and developing and providing climate analytical models and methodology. Financial regulators have focused on climate-related governance as well: for example, in 2019, the Prudential Regulation Authority, which regulates banks, insurers, and investment firms doing business in the United Kingdom, finalized guidelines requiring those firms to embed fully the consideration of climate risks into governance frameworks, including at the board level.12 Climate-related shareholder proposals have increased in Canada13 as well as globally.14 Many institutional investors are actively advocating for boards of companies to make changes to their companies' business models and adopt strategies to transition to a future lower-carbon economy. Climate Action 100+, for example, has over 360 investor members (including Canadian investor groups) representing more than US$34 trillion worldwide.15 It has identified over 160 corporations which are large greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters, and engages with them to encourage them to, among other things, introduce climate matters as a metric for executive compensation, to adopt TCFD, and to make changes in their business models to align their business strategies with the Paris Agreement.16

Stakeholder attention to the management of climate change–related risk and climate change–related disclosure has occurred alongside other important stakeholder interest trends: the growing emphasis on sustainable corporate long-term value creation and “good corporate citizenship.” In addition to the fact that climate change can be a core business issue for a board to consider, it is clear that paying attention to these stakeholder interests is consistent with the legal role and responsibility of directors in Canada. In contrast to the United States where the law favors “shareholder primacy,” the Supreme Court of Canada has instead affirmed “stakeholder primacy.” The Court has interpreted the provisions of corporations' statutes which say that directors and officers must act “honestly and in good faith with a view to the best interests of the corporation” to mean that, in exercising their fiduciary duty in oversight over a company's affairs and in decision-making, directors should:

- Recognize and balance the interests of all relevant stakeholders, which in the circumstances of any given case, may include shareholders, employees, suppliers, creditors, consumers, governments, and the environment;

- Recognize and balance both short-term and long-term interests (including those of stakeholders with competing short-term and long-term interests); and

- Reflect on the interests of the corporation both as an economic actor and as a “good corporate citizen.17

Put another way, for boards of directors in Canada, “good stakeholder relationships are good business and good for business.”18 In June 2019, the Canada Business Corporations Act, which governs a significant number of Canadian companies, was amended to make explicit that when considering the best interests of a corporation, directors may consider, among other things, the interests of stakeholders, the environment, and the long-term interests of the corporation.19

Incorporating Climate Change into the Overall Board Governance Framework

The key role of the board of directors is to oversee management of the company, including its core risk identification and management process, its business model and strategy, its financial performance, and its reporting to, and communications with, stakeholders. Directors have a duty to ask relevant questions in order to understand, provide appropriate oversight over, and make informed decisions in these areas. In connection with risk in particular, the board's role includes ensuring that adequate strategies are devised to identify, assess, manage, and mitigate risks, and then to monitor the implementation of those strategies. With respect to a company's short-, medium-, and long-term business strategy, business model, and financial planning, directors must ask questions to help them assess whether management is identifying, assessing, and reporting to the board on actual or potential impacts of risks and opportunities and identifying options or alternatives which may result in enhanced value creation.

At first instance, climate change is only one of many important areas in which directors must understand and assess risk and opportunity and their implications for the company's business model and strategy. The answers will differ from company to company, but the “big picture” question is the same: how is climate change likely to affect the company's business, operations, access to capital and value creation in its immediate planning horizon as well as in the medium and long term?

As is the case with all other important business issues, the board of directors must set the appropriate “tone at the top” with respect to the company's approach to climate change. In order to do this, the board should include oversight of climate issues within appropriate governance structures and mechanisms, and directors should understand and be able to talk meaningfully about the company's strategy in this regard.

While the board retains responsibility for overall oversight, one or more board committees should be charged with specific oversight of climate-related matters and their written mandates, including responsibility, meeting frequency, and process, should reflect this. Within typical board committee structures, the most likely choices for the primary oversight committee are: the risk committee, or if one does not exist, whichever committee is charged with risk oversight overall (usually the audit committee); or the environment, health and safety committee, to the extent that it is charged with oversight of all environmental issues. Depending on which committee has primary oversight, there are areas where the nature of the needed oversight will interact or overlap with other committees. These may include:

- The audit committee, to the extent that it involves the company's financial performance and oversees financial disclosure, investor communications, disclosure controls, and internal controls;

- The governance committee, to the extent that it focuses on overall regulatory-related compliance, board continuing education, and board and committee competency (and may wish to review whether climate change competency should be included in the board skills matrix);

- The human resources committee, to the extent that it focuses on compensation, including whether climate considerations, metrics, and targets should be built into senior officers' compensation and whether suitable incentives exist, generally, to motivate management oversight, and perhaps, innovation, in the climate context; and

- The environment, health, and safety committee, to the extent that it provides oversight, in particular, of physical climate impacts.

For companies that deem themselves to be particularly high risk in relation to climate change, a separate climate committee could be constituted, either as a formal board committee or as an ad hoc committee.

Collectively, the board committees charged with oversight of climate change–related matters should also review and assess the mechanisms in place at the management level in order to ensure that management has appropriate ways, including through internal committees, specific delegated individual responsibilities, and appropriate incentives, to assess and manage climate change–related risks and opportunities and to translate these assessments into strategic decisions. Ultimately, as well, the relevant board committee(s) must ensure that appropriate climate-related reporting, both with respect to scope and frequency, are provided to them as well as to the board itself so that decision-making occurs at the appropriate level.

Understanding the Dynamic of Climate Risk, Climate Opportunity, and Financial Impact

It is critical to effective oversight for the board of directors to have a fundamental understanding of the material climate-related risks and opportunities that may affect the company. It has been misconceived that climate change–related risks and opportunities are substantially confined to those companies that emit high levels of GHGs.20 In fact, climate change–related risks and opportunities are much broader in nature, application, and scope, and much more complex. They will affect different companies differently; for some companies, climate change may not present material risks or opportunities but that cannot be determined without an informed examination. The factors that will govern the nature and extent of climate change–related risks and opportunities, as well as their financial and strategic impacts, include:

- The type of industry in which the company operates;

- The nature of its products and services and key factors underlying their demand;

- Its business model;

- The nature of the competition it faces within its industry;

- The physical locations and political jurisdictions in which the company's head office and subsidiaries exist, or in which they make, distribute and sell products or services, or own and operate properties and physical assets; and

- The physical locations and political jurisdictions in which key constituents of the company's supply chain exist and those through which raw materials or inputs must travel to reach the company's production, distribution or sales locations.

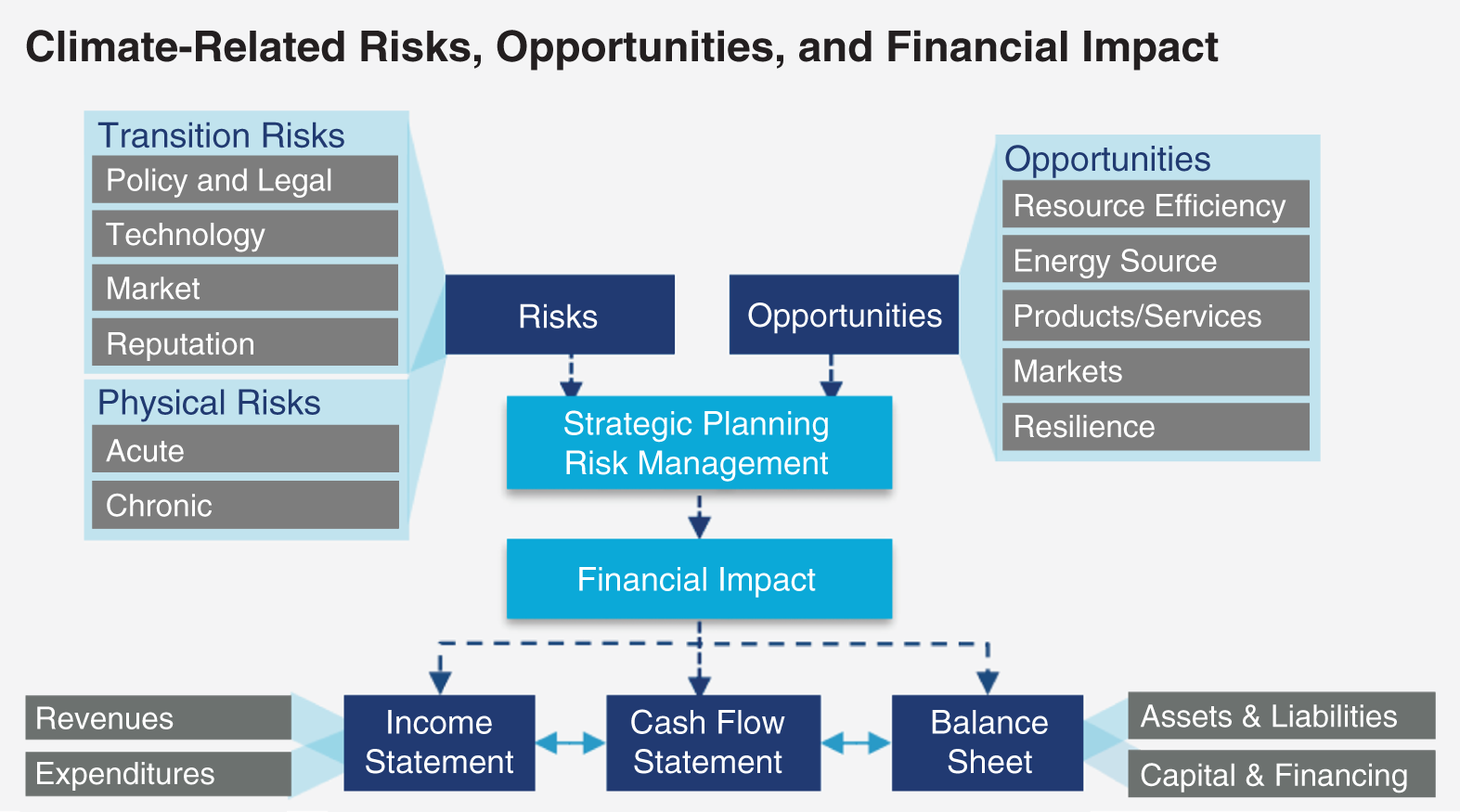

FIGURE 15.1 Climate-Related Risks, Opportunities, and Financial Impact

A number of frameworks exist to classify and identify these risks and opportunities.21 The TCFD recommendations include the useful schematic22 in Figure 15.1.

Climate Change–Related Risks

The TCFD framework identifies two key categories of risk,23 physical risk and transition risk, and recommends that companies identify and evaluate them from short-term and forward-looking medium-term and long-term perspectives.24

Physical risks arise from the increased frequency and severity of weather and climate-related events that can damage property or affect trade. These include risks from acute events, such as excessive precipitation causing floods, hurricanes, heavy winds and tornadoes, heat waves, excessive snowfall, or severe flash freeze/thaw events, and risks from chronic (slower onset) events, such as sea level rise, ocean acidification, sustained increases in temperatures, droughts, long-term water shortage or water quality issues, long-term changes in air or ocean currents, soil degradation, changes in snow cover, permafrost degradation, or ecosystem degradation. For businesses, acute or chronic events may damage or have direct or indirect negative impacts on property, assets or infrastructure, business continuity, supply chains, transportation needs, distribution networks and other trade arrangements with customers and intermediaries, and employee health and safety. Direct impacts are most easily observed and quantified, and, with appropriate historical data and access to climate models or climate analytics, companies may be reasonably able to foresee them. Indirect impacts are very different—these are impacts that may more broadly affect economies or the human or natural environment, such as changes in global trade routes, changes in agricultural productivity, migration, impacts on human health, climate-induced conflicts, availability of natural resources, or changes in macroeconomic indicators such as GDP, employment, and interest rates. Indirect impacts on corporate value chains are both more difficult to predict and to quantify.

The financial impacts of direct and indirect physical impacts could include, for example:

- Reduced revenues (such as losses arising from business interruptions, reduced asset productivity, or reduced consumer demand);

- Increased operating costs (including, for example, for repairs, increased insurance premiums, increased energy costs for heat waves or cold snaps, or negative impacts on workforces);

- Increased capital expenditures (such as the cost of repairs to, or retrofitting damaged or climate-vulnerable infrastructure, or temporarily or permanently moving to and equipping new sites or locations);

- Early retirement of assets or asset write-offs;

- Reserves write-offs (for mining companies and oil and gas producers); and

- Higher cost of, or more limited access to, capital or insurance.

In the 2018 annual voluntary corporate survey by CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project), for example: Coca-Cola identified that water shortages may prevent it from making its soft drink products and Intel Corp. identified that water shortages will adversely impact the semiconductor manufacturing process; Walt Disney Co. commented that excessive heat may prevent vacationers from going to its theme parks; AT&T reported that wildfires and hurricanes may knock out its cell towers, causing extensive repair costs, potential relocation of towers, and additional hardening of its network; and Bank of America identified flood risk to homeowners as a reason for anticipating higher rates of mortgage defaults.25 Visa Inc. went further, noting that chronic events may increase the likelihood of global pandemics and more armed conflicts, causing fewer people to travel, and hence reducing its foreign exchange revenues!26

Transition risks result from the transition or adjustment to a lower carbon economy. These may include technology, market, and policy and legal changes, which may often overlap or interconnect. Ultimately they may prompt a reassessment of the value of assets and business strategies as both costs and opportunities become apparent, and may result in the same sorts of financial impacts as described above (albeit for different causal reasons). In addition, these changes may pose reputational risk as a company assesses how exposed its corporate identity or brand will be due to its response, or perceived lack of response, to these changes, including how these will affect the attitudes of consumers, employees, shareholders, and other providers of capital. The financial impacts of transition risks may include “stranding” assets, that is, the repricing or write-downs of carbon intensive assets (i.e., oil, natural gas, or coal) that could become “stranded,” meaning unusable or reduced to lower/zero value.

Technology risk may come from the adoption of technological improvements or innovations that support the transition to a low carbon, energy-efficient economy. For example, the development and use of new technologies including renewable energy, battery storage, energy efficiency, and carbon capture and storage may affect the competitiveness of certain companies, their production and distribution costs, their research and development expenditures, and, ultimately, customer preferences for their products and services.

Market risk is the possibility that there may be a change in consumer behavior or customer preferences in the demand for certain commodities, products, or services as climate-related risks and opportunities are increasingly understood and evaluated. For companies in the materials/industrials sector, for example, changes in product preferences may occur as consumers and businesses demand materials that enhance energy efficiency and facilitate environmental certifications, such as LEED.27

Policy and legal risks encompass policy (or regulatory) actions of two sorts: those intended to constrain activities that contribute to the adverse effect of climate change; and those that promote adaptation. In the former category are the proliferating number of federal, provincial, and foreign GHG emissions regulation mechanisms, including emissions reduction targets, “hard” or intensity-based emission caps, and carbon taxes. Compliance with these rules may significantly affect the operations and financial performance of companies doing business, owning assets, or having key supply chain elements, in multiple affected jurisdictions, and noncompliance may result in fines or penalties. Also in this category are increased risks to some companies for failure to obtain licenses, project approvals, permits, or environmental impact assessment approvals for proposals involving significant GHG emissions (including upstream and downstream emissions).28 Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom and some parts of the USA are increasingly witnessing contentious administrative and legal processes for the approval of oil and gas pipelines, energy-related infrastructure, and new oil, gas, and coal projects.29 In the second category, policy actions to promote adaptation could include, for example, stipulating greater water efficiency measures, shifting energy sources toward lower emissions sources, promoting some (and simultaneously limiting other) types of products (such as incentives by some jurisdictions for the production of electric vehicles), adopting energy-efficiency solutions and promoting more sustainable land-use practices.

Litigation Risk—A Special Category

Litigation risk30 has become particularly important to companies and their insurers in light of proliferating global climate litigation. Boards need to be wary of climate litigation, as, even if unsuccessful, it may have significant cost implications for the company (and its insurers) as well as reputational implications, and could potentially impact the investment/divestment decisions of investors and other capital providers.

In addition to the potential for litigation in relation to permits or approvals for new activities or infrastructure (described above), directors should be aware of three trends:

- Multiplying litigation against major carbon-producers seeking damages relating to their alleged causal connection in global warming (in order to fund adaptation costs);

- Investor litigation under applicable securities laws on the grounds of companies' failures to disclose or misrepresent the risks or costs posed to them by climate change; and

- Litigation against companies for causing personal injury or damage to property of others as a result of failure to adapt owned or operated infrastructure.

Litigation in the first category was fueled by the 2014 publication of a study by Richard Heede31 which mapped and quantified the cumulative emissions of the 90 largest carbon producers from 1854 to 2010—dubbed the “Carbon Majors.” These cumulative emissions results are updated annually by climate scientists and advocates,32 and they are cited to support ongoing litigation claims.33

In the United States, a country whose litigation trends are closely followed by Canadian companies and institutional investors, a significant number of cases were filed in 2017 and 2018 by major cities, counties, one state (Rhode Island) and the West Coast's largest association of fishermen, against a long list of oil, natural gas, and coal companies (including Encana Corp, and Suncor Inc., both Canadian companies identified as Carbon Majors). The plaintiffs brought various claims under U.S. state common law, including under several torts similar to those under Canadian common law:

- Private nuisance (i.e., where one party uses its property in a way that substantially causes damages to another's property or substantially and unreasonably interferes with the use of another person's property), where global warming is alleged to be the nuisance, with GHG emissions contributing to it;

- Public nuisance (nuisance that affects public property or public rights);

- Negligence;

- Design defect (where fossil fuels are alleged to be a product whose design with GHG emissions makes them inherently dangerous);

- Failure to warn (no adequate warning of the design defect); and

- Trespass (knowing physical intrusion of the warming/GHG emissions onto another person's property),

and in one case, a claim alleging liability for violation of state environmental rights legislation.34

These lawsuits are being vigorously defended. The plaintiffs face significant legal issues including: the political question doctrine, which essentially says that political issues are non-justiciable; the substantive issue of proof of causation, that is, the link between the defendants' behavior and the alleged harm suffered by the plaintiffs; and standing, that is, demonstrating that the plaintiff has sufficient connection to the issue to support its participation in the case. Two U.S. cases that were moved to and adjudicated at the U.S. federal court level, those brought by Oakland and New York City, were dismissed in 2018 by lower courts on the basis of the political question doctrine, although both have been appealed. In the Oakland case, the Court stated that it accepted the science behind global warming yet the problem “deserves a solution on a more vast scale than can be supplied by a district judge or jury in a public nuisance case”35 and noted that the relief sought could affect the conduct of energy producers and energy policies worldwide.

At the time of writing, there is no Canadian lawsuit alleging corporate responsibility for climate change.36 The media, however, has reported that some municipalities in British Columbia are considering such class action litigation and are requesting that Province to enact “strict liability” legislation,37 much like that which allowed tobacco companies to be held liable, without proof of fault, for the health care costs of smoking. It is also known that climate advocacy groups are counselling other regions and cities to consider similar lawsuits.38

With respect to disclosure-focused litigation, lawsuits have been brought in Australia and the United States.39 A key lawsuit was launched in 2018 by the State of New York against Exxon Mobil Corporation alleging securities law and general common law fraud for alleged pervasive intentional misstatements to investors and others regarding its management of climate-related risks.40 The State alleged that Exxon has repeatedly and falsely assured investors that it has taken active and consistent steps to protect the company's value from the risk that climate change poses to its business. In particular, Exxon's disclosed claims regarding its application of proxy costs of GHG emissions in its economic projections are alleged to be materially false and misleading.41 That lawsuit spawned shareholder lawsuits against Exxon in 2018 and 2019 and, importantly, lawsuits specifically against its directors and executive officers.42 Securities class action lawsuits have also been brought against electrical utility companies in California, including PG&E Corp, touted in the media as climate change's first bankruptcy.43 There, equity and bond investors have alleged that these companies and their underwriters misrepresented the companies' exposure to wildfires, including by misrepresenting the steps taken to improve and maintain their infrastructure in light of known climate change conditions and wildfire risks.

At the time of writing, no disclosure lawsuits have emerged in Canada44 but the possibility of such claims has received academic comment.45 In their analysis, the authors identified three potential types of disclosure-related claims that might surface in Canada: failure to discuss financially material risks of the transition to low-carbon strategies (including as necessitated by regulatory and societal factors); material misstatements of the value of a company's assets in light of “stranded assets”; or material misstatements relating to the risks of continued extraction and use of a high-carbon product, such as oil, gas, or coal.

For companies which develop, design, build, own, operate, maintain, or repair infrastructure,46 as severe weather events have increased in frequency, and localized weather and climate data has become more readily available, it may be reasonably foreseeable that acute events could stress or damage infrastructure and shorten its anticipated useful life. Equally, it may be reasonably foreseeable that impacts from incremental or chronic climate-related events could exacerbate this stress or damage. There may also be cascading and cumulative direct or indirect effects. Where personal injury, health, or property damage occurs, parties who do not have insurance coverage or access to compensation through a disaster relief or special compensatory fund may bring lawsuits, based, likely, on common law claims of negligence or nuisance, against the owners and operators of the infrastructure, as well as relevant design professionals. Lawsuits of this nature already exist in the United States, Australia, and Canada.47

Within the spectrum of litigation risk for a company, it is also possible that directors may be targeted for allegedly mismanaging climate change–related matters in their business, financial, investment, acquisition, or disposition decisions.48 Canadian corporations' statutes generally say that directors owe a fiduciary duty to the corporation to act honestly, in good faith and with a view to the best interests of the corporation, and, in so doing, to exercise the care, diligence, and skill that a reasonably prudent person would exercise in comparable circumstances.49 With this, however, Canadian law embraces the “business judgment rule,”50 in which a court will generally defer to a board's decision if: (i) the decision has been made on an informed basis after following a reasonable process (i.e., directors asked for and received relevant information, asked, and received answers to relevant questions, relied on qualified advisors in circumstances where expert advice was needed or warranted, and took the time to review and deliberate the matter) and (ii) the decision lies within a range of reasonableness, that is, within a reasonable range of alternatives. Properly conducted process, including asking questions, will protect directors.

Climate Change–Related Opportunities

In any business situation in which there is risk, there is usually opportunity, and climate change is no exception. There are many different ways to envision opportunities arising from the physical impacts of climate change and from the transition to a lower carbon economy. Generally, under the TCFD typology, these are viewed as opportunities for decreased costs, higher revenues, competitive advantage, and reputational advantage in:

- Resource efficiency and costs savings;

- The adoption of low-emission energy sources;

- The development of new products and services;

- Access to new markets; and

- Building climate-related resilience along the supply chain.51

Cost savings might be expected, for example, from increased energy efficiency but also potentially in relation to broader materials, water and waste management. As well, with respect to physical risks, cost savings may also result from “learning” in respect of earlier acute events, that is, taking measures to avoid or lessen the nature and volume of earlier costs experienced. Business opportunities may result from strategies directed at developing or investing in products, services or technologies that can directly profit from the changing climate or the transition to a low-carbon economy, including as a result of changing consumer behavior or changing consumer preferences. “Low carbon” or “carbon neutral” labeled products are one example, but so, possibly, are water-permeable pavements, efficient building cooling products, and ceiling fans. Existing products and services may also experience greater demand as the climate changes. In the 2018 voluntary CDP Climate Change survey, for example, Apple indicated that more climate-related disasters will make its iPhones more vital and Merck & Co. indicated that it could expect higher demand for its tropical and weather-related illness products.52 There may also be opportunity through direct investment in low-carbon or “clean” technologies and services. Access to new markets could result from collaborating with others focusing on the shift to a lower-carbon economy while new capital-raising opportunities might result from the creation of new “green” financial products and financing “green” services or infrastructure.

The concept of resilience, in relation to climate change, refers to a company's developing adaptive capacity to respond to climate change to better manage the associated risks and seize opportunities, including the ability to respond to transition risks and physical risks.53 The TCFD commented that opportunities for resilience might be particularly relevant for: companies with long-lived fixed assets (i.e., infrastructure) or extensive supply or distribution networks; companies that depend critically on utility, infrastructure networks or natural resources in their value chain; and those that might require longer-term financing and investment.54

Understanding the Tools to Evaluate Climate Change–Related Risks and Opportunities

In order to understand the nature and importance of the potential physical and transition risks and opportunities facing the company over various time horizons, directors must know what processes are being used to: measure and assess the importance of these risks; identify new ones as they emerge; monitor the status of these risks; and assess resilience to these risks.

The TCFD framework recommends that a company use scenario analysis, incorporating multiple sets of scenarios.55 This technique is often used for other purposes in risk management, strategy, and financial planning, but it is nascent in the climate context. Scenarios are hypothetical constructs which yield a series of potential future outcomes based on specific assumptions, factors, and methodologies, such as the assumed global temperature rise, the energy mix, or whether the transition to a low carbon economy happens smoothly or abruptly. Scenarios can yield a qualitative or quantitative narrative of what might happen in the future and, as a result, help management and boards of directors to think through different possible futures.

For the purposes of physical risk analysis, a company might instead do prediction models for short- and medium-term analysis using existing historical data and probability modeling. Given uncertainty in climate policy and, in particular, the potential cascading impacts of climate change, scenario analysis may be more useful for assessing direct impact of physical risk in the long term, or for looking at more nebulous indirect physical risk impacts in the short, medium, or long term.56

Companies which own, operate, or maintain important infrastructure can also conduct climate-related resilience and vulnerability assessments57of these assets using approved engineering techniques. These assessments can then inform decisions regarding major upgrades, design features, site location, and other climate adaptation measures.

For all but the largest companies, conducting climate scenario analysis is likely to be highly complex and costly. Although some publicly available scenario models exist,58 there are many ways, many models, and new ways and models are evolving, to conduct scenario analysis. There is a lack of guidelines, standards, protocols, and consistent practices in this area.59 In most cases, companies will need to seek outside expert assistance for this purpose.

For physical risk analysis, there may be limitations on the availability of relevant historical data or climate prediction data for all of the locations that a company may need to look at along its asset ownership, production, distribution, and supply chain. The Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance observed in its Final Report that, while quality scientific climate data exists in Canada, there are no centralized public sources of such information, or accessible analytical models, for assessing it, and the Panel made recommendations for the development of such resources.60 Companies may need to seek outside expert assistance and incur significant costs to acquire data and prediction models for this purpose.

What the Board Needs to Know About Risk and Opportunities Analyses

As the foregoing indicates, a board of directors should understand what the potential physical and transition risks are, and how important (material) these are likely to be within and beyond the company's immediate planning horizon. Questions that directors should ask include:

- What time frames are appropriate for this purpose (i.e., what is the short term, the medium term and the long term)?

- What data and what processes are management using to assess these risks and their actual and potential financial impacts?

- How often is management updating its analyses? How often should we (the board and relevant committees) be updated?

- What processes is management putting in place to identify new risks as they emerge?

- How important is this analysis to the company in terms of availability of insurance or debt and equity capital?

- Is management assessing the physical risks as well to the company's supply chain and distributors?

- Is reliable location-specific data available for these purposes?

- Is management conducting climate vulnerability and resilience tests for important infrastructure (using appropriate methods and experts) and, if so, how often are tests being conducted?

- Is management using external expertise where that it is warranted?

- Does the board have timely access to reports from, or presentations by, relevant external experts?

While some risks will not be as important for some companies as for others, policy and regulatory risks are likely to influence almost every company in some way (and they are frequently cited risks by companies in both voluntary and regulatory disclosures).61 Directors should be regularly briefed about policy and regulatory trends that may have an impact on the company in the short, medium, or long term, and which may be important factors in shaping long-term strategy. Briefings by management, and where applicable, outside legal or other specialized advisors, on key developments, should occur at least annually, and more frequently for companies in sectors most exposed to these types of risks. For directors of companies involved in the energy or utilities sectors, in particular, briefings should occur in advance of seeking key environmental approvals or permits for new activity or related infrastructure build, and directors should also question management about the content and readiness of communications strategies and legal strategies with respect to these approval processes.

Similar questions should be asked about the identification of, and quantification of potential financial impacts relating to, climate change–related opportunities. One key question in this regard is whether management is suitably motivated and incentivized (by compensation or otherwise) to look for such opportunities. Other questions that should be asked include:

- Is management exploring and considering innovation and technology-related opportunities?

- If so, what capital expenditure will be involved?

- Is management looking at these types of opportunities, in general, in making decisions about capital allocation in the relevant time horizons?

- Are we (the board and the relevant board committees) being briefed and updated frequently enough on these matters?

Directors also need to understand when and how management is using scenario analysis and climate prediction models as tools, as well as what type of data is being used, where it was sourced, and what the key assumptions and factors are. The board should ask management about its confidence in the usefulness and reliability of both the data and the analysis. In the context of scenario analysis, the board should ask questions to determine whether management has made choices in factors and assumptions that might tilt the analysis in a direction that will affect a desired outcome. If outside experts are being used, directors should consider requesting one or more presentations by these experts in order to allow it to ask questions directly. If quantitative analysis is being done with respect to multiple scenarios, management will produce an array of numbers, which must be distilled for the board so that it can clearly understand the signals they produce for the company's resiliency, business model, and strategy. Ultimately, boards need to know whether scenario analysis and climate modelling is being conducted in such a way that it can meaningfully inform the board's oversight processes and decision-making.

What the Board Needs to Know About Climate-Related Risk Management and Strategic Planning

As climate change–related risks and their potential financial impacts are identified, a board of directors needs to understand what systems and processes management will use to mitigate and manage them, and what mechanisms are being developed in order to respond to changes in risks and the risk profile over time. For physical risks, directors should ask, at first instance, whether (and what) comprehensive remedial and contingency plans are in place to deal with severe weather events. A company's approach to managing physical risks may make a significant difference to its ability to withstand climate change impacts over time. Risk mitigation may involve planning and de-risking processes, finance and reinsurance/risk transfer, knowledge and information generation, human resources and adjusting supply chain mechanisms or capital allocation to, and direct investment in, technology or engineered infrastructure. For transition risks, a board might question whether better internal processes and direct investment into technology might mitigate risk, as well as allow a company to take advantage of opportunities and to gain competitive or reputational advantages. Other questions directors might ask include:

- Does the company have a system or process for ongoing climate-change risk audit?

- Is climate change–related risk embedded in the company's overall enterprise risk management system?

- What strategies are in place to mitigate or manage risks in the short, medium, and long term, and how frequently are these being reviewed?

- Is the company dedicating sufficient resources, human and otherwise, to identifying, implementing, and monitoring processes intended to deal with these issues?

- Is the company participating in relevant industry initiatives?

- How is management engaging with critical capital providers, such as its banks and project finance providers in terms of their questions with respect to these matters?

- Are we (the board and the relevant committees) being briefed and updated frequently enough on these matters?

Once a company has assessed climate change–related risks and opportunities, management should be in a position to identify their importance or materiality to the company, and translate them into a meaningful analysis and set of recommendations for the company's immediate planning horizon, as well as medium- and long-term strategies. Directors should ask if this is being done, and, in turn, ask questions about the analysis and recommendations, including to understand how frequently recommendations are reviewed and updated, when and how strategies will be implemented, and how their implementation will be monitored. For example, directors might ask whether management recommends use of an internal carbon price. Ultimately, the board of directors must ask questions to allow them to assess whether changes to the company's business model will be needed in order for the company to succeed in the long term.

What the Board Needs to Know About Climate Change–Related Disclosure

Federal and most provincial laws, as well as laws in other countries where a company may do business, require certain industrial facilities to report GHG emissions at or beyond threshold levels and to separately report emission levels and reductions over specific time periods in compliance with regulation aimed at curbing GHG emissions. This is an element of a company's legal compliance obligations, and boards should exercise oversight over this in the same manner as for other compliance/regulatory matters.

All companies, whether public or private, prepare audited and unaudited financial reports and disclose financial metrics to their shareholders, their principal lenders and applicable corporate or other regulators. For financial statements purposes, a board of directors should ask whether management is taking climate-related matters into account in estimating important contingencies, or for the valuation of assets and liabilities, including, as applicable, fossil fuel resource reserves, infrastructure or investments, including to determine if there is a prospect that these assets are overvalued—that is, is there a risk that these assets will become “stranded”?

Special disclosure obligations apply to public companies. A public company distributing its securities in Canada has obligations to make continuous and timely disclosures in documents filed with securities regulators and sent to security holders, including its annual information form and quarterly and annual management's discussion and analysis (MD&A). Under applicable securities laws, a company must disclose risks to it and its business that would be most likely to influence an investor's decision to purchase its securities, as well as commitments, events, risks, or uncertainties that it reasonably believes will materially affect its future performance. Climate change–related risks and opportunities must be considered in this context. Public companies must also disclose their policies and procedures related to risk management and oversight, including oversight of their disclosure obligations themselves. Certain other types of required disclosure may encompass climate-related matters, including those relating to material litigation, regulatory penalties or sanctions, and liabilities, permits, or environmental conditions affecting operations.

For the purpose of continuous disclosure obligations, the concept of materiality typically determines what information a company must disclose. In Canada, materiality is assessed by reference to the so-called “reasonable investor” standard: Information is likely to be material if a reasonable investor's decision whether to buy, sell, or hold the company's securities is likely to be influenced or changed if the information is omitted or misstated.62 The question of what information is “material” at any time is an objective determination that a company must make based on its own facts and circumstances at the time disclosure is being made, including what it believes its security holders think is important.

The question of what is “material” in the climate change context has been debated in Canada for well over ten years. Following issuer and investor consultations, the CSA first published guidance in 2010 for disclosure on environmental issues generally.63 This guidance contains a number of principles for issuers seeking to make materiality determinations, including: where doubt exists, disclose. In 2018, the CSA concluded64 that it would not then recommend any significant overall changes to securities law requirements with respect to the disclosure of climate change–related risk and opportunities, and would not recommend new prescriptive disclosures or a “comply-or-explain” framework. The CSA did state, however, that it would seek to introduce new rules mandating disclosure (i.e., not subject to materiality) with respect to a company's governance process in relation to material risks and opportunities, including the board's responsibility for oversight and the role played by management, as well as disclosure of how the issuer oversees the identification, assessment and management of material risks.65 In stating this, the CSA noted that such disclosures were almost universally requested by investors, and expressly noted that the TCFD framework recommends disclosure, irrespective of materiality, of:

- The board of directors' oversight of climate change–related risks and opportunities;

- Management's role in assessing and managing climate change–related risks and opportunities;

- The process used by the organization to identify and assess climate-change related risks; and

- How such processes are integrated into the organization's overall risk management process.

More recently, the CSA responded to concerns of smaller issuers who sought more guidance to help them identify and improve their disclosure of material climate change–related risks. In August, 2019, the CSA published a further staff notice, which used the TCFD risk typology and included questions, including governance-related questions, that issuers might use.66 While the CSA did not articulate new principles for assessing materiality, it did cite resources that issuers might refer to, including the work of the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB).67 It also suggested that issuers might consider using external resources and benchmarking their climate change–related disclosure against their peers.68

Given the stated intentions of the CSA to introduce rules to mandate disclosure regarding climate-related governance and the increasing importance accorded to governance-related disclosure by investors, it would be prudent for a board of directors to proactively review having the company make disclosure along the lines being proposed by the CSA (as mirrored in the TCFD). In this respect, any such disclosure should be reviewed through the company's customary disclosure processes and protocols, including customary board committee and board review.

In response to requests for climate-related information from stakeholders other than investors, many companies now make voluntary additional climate-related disclosures outside their mainstream regulatory filings. These typically occur in corporate responsibility or sustainability reports, through answers (publicly available) to the voluntary climate questionnaires of CDP, through website disclosures, or in climate risk and resilience reports.69 Many companies make disclosures under sustainability reporting frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or SASB.

Directors of a company that discloses such voluntary information should ensure that oversight of this type of reporting is included in the company's public relations, communications and disclosure control processes, as it may have broad implications for corporate reputation and stakeholder relationships. It will also be important for the board to ask whether appropriate processes are in place to ensure that all information being disclosed, whether through voluntary or mandatory disclosures, is being disclosed on a consistent basis.

The TCFD framework is gaining momentum in Canada and elsewhere (sometimes integrated with other frameworks).70 The federal government stated in its spring 2019 Budget that it “supports the TCFD's voluntary international disclosure standards and a phased approach to adopting them by major Canadian companies, as appropriate.”71 In a speech given at approximately the same time, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney said: “The momentum behind TCFD's voluntary disclosure is creating a virtuous circle by encouraging learning by doing. As companies apply the recommendations and as investors increasingly differentiate between firms based on this information, adoption will continue to spread, disclosure will become more decision-useful and efficient, and its impact will grow.”72 More recently, the Final Report of the Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance endorsed TCFD, recommending a phased comply-or-explain process for compliance by all Canadian companies. The Expert Panel recommended disclosure of climate change–related governance processes in the first phase (along with certain aspects of strategy, risk management and metrics and targets), urging that large companies complete this phase as soon as possible, and, in any case, before the end of 2022, with smaller companies urged to complete it by the end of 2024.73

The TCFD recommendations are designed for voluntary use by all types of companies in their mainstream financial filings (i.e., those filed with securities and/or industry regulators), not their voluntary filings. Importantly, TCFD incorporates a “local user” concept of materiality, that is, a company should assess materiality using the same concept as it would otherwise use (i.e., in Canada, the “reasonable investor” standard).74 In addition to the mandatory disclosures referred to above, TCFD recommends that, if deemed material, a company should disclose:

- Actual and potential impacts of climate-related risks and opportunities on the organization's businesses, strategy, and financial planning;

- Metrics and targets used to assess and manage relevant climate-related risks and opportunities;

- Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 GHG emissions; and

- The resilience of the company's strategy; and using scenario analysis, including a 2°C or lower scenario.75

The TCFD provides supplementary guidance for banks, insurance companies, asset owners, and asset managers, as well as for certain nonfinancial business sectors potentially most affected by climate change: energy, transportation, materials, and buildings (including real estate) and agriculture, food, and forest products.

If a company has not yet looked at adopting some or all of the TCFD recommendations, it would be prudent for a board of directors to ask management whether the company should or will use the TCFD framework. Where management is recommending it, the board should be briefed on the critical time frame for implementing it (i.e., will it be adopted in stages? What information needs to be gathered? Is outside advice being sought?) and steps that management will take. Certain areas of TCFD may well prove more difficult to adopt than others, including, in particular the identification of appropriate metrics and targets for the company. The board may wish to recommend the use of external consultants in this regard.76 The board of directors, or the appropriate board committee, should then decide on an appropriate framework for monitoring progress and for oversight as stages are implemented.

Whether or not a company uses the TCFD framework or makes disclosures under CDP, SASB, or any other voluntary reporting framework, it will be important for a public company to manage its potential for climate change–related disclosure liability under applicable securities laws. Canadian securities regulators have a wide variety of powers to prosecute companies, their directors and responsible officers for disclosure offences, including breaches of the rules requiring disclosure of material information in continuous disclosure documents, or, more broadly, where offering documents, financial statements and documents required to be filed under securities laws contain statements that, in a material respect and at the time and in light of the circumstances in which they are made, are misleading or untrue, or do not state a fact that is required to be stated or that is necessary to make the statements not misleading.77 For these purposes, securities regulators (and Canadian courts) usually apply the “reasonable investor” standard.

Companies, and their directors and responsible officers, may also be sued by investors for damages under the civil liability provisions of provincial securities legislation. This may occur if investors purchase treasury securities under an offering in which the offering document contains a “misrepresentation.” It may also occur where investors purchase or sell the company's securities in the secondary market, if, at the time of their purchase or sale, the company has failed to disclose a “material change” in compliance with securities laws or its continuous disclosure documents, other documents made generally available to their investors (including website disclosures, corporate responsibility, climate resilience or sustainability reports) or public oral statements made on behalf of the company (i.e., by management or directors) contain a “misrepresentation.”78

A “misrepresentation” is an untrue statement of a “material fact” or an omission to state a “material fact” that is required to be stated or that is necessary to make a statement not misleading in light of the circumstances in which it was made. Whether a fact is a “material fact” is measured by a “market impact” test: would that fact reasonably be expected to have a significant effect on the market price or value of the relevant securities. A “material change” means a change in the business, operations or capital of the company that would reasonably be expected to have a significant effect on the market price or value of its securities or a decision made by its board to implement such a change.79

For any company, the answer to the question of what climate change–related information may be material for a “reasonable investor” or what might, more narrowly, constitute a “material fact” is evolving, and will continue to evolve, as climate change impacts evolve. For the board of directors, the question of how management and the company's disclosure committee are determining materiality in this context must be reviewed, on an ongoing basis, by the appropriate management and board committee(s) and the board itself. Directors should ensure that they receive briefings and advice, as needed, on these matters from the company's general counsel, and, as desired, the company's external securities law counsel. As well, directors should consider requesting periodic briefings on developing trends in climate change–related disclosure.

Closing Comments

Appropriate oversight by a company's board of directors is critical to a company's ability to effectively address risks and opportunities of all kinds, to create value for its shareholders and to deal with the interests of its stakeholders and community. As boards of directors in Canada and elsewhere in the world deal increasingly with climate change, “best practices” in both governance and disclosure will emerge, and these in turn will evolve with experience, stakeholder expectations, the markets, as applicable, and the legal, regulatory, and policy environment. Prudent boards of directors of Canadian companies should monitor these developments.

About the Author

Patricia A. Koval is a corporate director and lawyer based in Toronto, Ontario. She is retired senior partner of Torys LLP, where she specialized in corporate finance, securities law, and corporate governance. Among other things, she co-chaired the firm's Climate Change and Emissions Trading practice group, and was a frequent speaker and author and contributor to articles on disclosure, governance, and potential legal liability associated with climate change. Pat is a contributing author to The Law of Climate Change in Canada (Canada Law Book) and has been a member for over ten years of University of Toronto's Environmental Finance Advisory Committee, where she has organized and spoken at many programs on carbon finance. She was an Adjunct Professor at University of Toronto for more than 15 years.

Pat is currently an independent director of Trans Mountain Corporation and of the Independent Electricity System Ontario (IESO), and serves on the Ontario Chapter Executive Board of the Institute of Corporate Directors (ICD) and the Canadian Performance Reporting Board of CPA Canada. She is the chair of Toronto and Region Conservation Foundation, a member of the Ontario Regional Board of the Nature Conservancy of Canada and a board member of several other Canadian and U.S. organizations focused on conservation and the dual pillars of climate change and biodiversity. She is the former chair of World Wildlife Fund Canada and former member of Greening Greater Toronto, an initiative of CivicAction Alliance.

Pat graduated from the joint MBA/JD program at Schulich School of Business and Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto, Canada, after completing an Hons BA (economics).

Notes

- 1. World Economic Forum, “The Global Risks Report 2019,” https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2019.

- 2. See, for example, Koval, Patricia, Dyck, Tyson, and Pickersgill, Michael, “Climate Change Disclosure Requirements,” Corporate Disclosure, Volume II, No. 2 (2008), at p. 74 (published by Federated Press).

- 3. Carney, Mark, “Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon—climate change and financial stability,” Bank of England (29 September 2015), http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/speeches/2015/844.aspx#.

- 4. Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, “Final Report: Recommendations of the Task-Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures” (June 2017), https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/publications/final-recommendations-report/ [“TCFD Final Report”].

- 5. Task Force on Climate-Related Disclosures, “TCFD: 2018 Status Report”(September 2018), https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/publications/tcfd-2018-status-report/ and “Task Force on Climate-Related Disclosures:2019 Report” (June 2019), https://www.fsb.org/2019/06/task-force-on-climate-related-financial-disclosures-2019-status-report/ [“TCFD 2019 Status Report”]. See also Carney, Mark “A New Horizon” (21 March 2019), www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/speeches/default.aspx.

- 6. Canadian Securities Administrators, “CSA Staff Notice 51-354: Report on Climate Change–Related Disclosure Project” (April 2018), https://www.osc.gov.on.ca/en/SecuritiesLaw_csa_20180405_51-354_disclosure.project.htm [“CSA Staff Notice”].

- 7. Ibid. at p. 35.

- 8. Ibid. at p. 37. These proposed requirements are similar to the mandatory disclosure requirements under TCFD.

- 9. Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance, “Final Report of the Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance,” Government of Canada (June 2019), http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2019/eccc/En4-350-2-2019-eng.pdf [“Final Report”].

- 10. For example, investment managers such as BlackRock and State Street Global Advisors have made public statements regarding their expectations that board members of companies they invest in will evaluate climate change–related risk, risk mitigation, and adaptation strategies. See: BlackRock, 2018, “BlackRock Investment Stewardship Engagement Priorities for 2018,” https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/publication/blk-stewardship-2018-priorities-final.pdf (link as of April 13, 2019) and State Street Global Advisors, 2016, “Climate Change Risk Oversight Framework for Directors,” https://ssga.com/investment-topics/environmental-social-governance/2018/06/climate-change-risk-oversight_jun%202018.pdf (link as of April 13, 2019).

- 11. For example, United Nations Environmental Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP-FI) has ongoing pilot projects for banks, insurance companies, and pension funds and institutional investors. See its website: https://www.unepfi.org.

- 12. These guidelines require firms to: (i) assign responsibility for oversight of these risks to specific senior role holders; (ii) consider climate change in line with their board-approved risk appetites; (iii) make regular use of scenario analysis to test strategic resilience; and (iv) develop and maintain an appropriate disclosure of climate risks. See, “The New Horizon,” supra, note 5, at p. 6.

- 13. For example, Canada's six major banks received shareholder proposals for their 2019 annual meetings requesting their boards of directors to implement TCFD.

- 14. See, for example, Horster, M., and Papadopoulos, K. (2019), “Climate Change and Proxy Voting in the U.S. and Europe,” https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2019/01/07/comate-change-and-proxy-voting-in-the-u-s-and-europe/.

- 15. See their website, www.climateaction100.org (last accessed April 24, 2019).

- 16. For example, 2019 announcements by BP Oil, Glencore Inc., Shell, and Equinor (formerly Statoil) agreeing to align their business strategies with the goals of the Paris Agreement, Ibid.

- 17. See, for example, BCE Inc. v. 1976 Debentureholders, 2008 SCC 69, [2008] 3 SCR 560, and Peoples Department Stores Inc. (Trustee of) v. Wise, 2004 SCC 68,[2004] 3 SCR 461.

- 18. “Wachtell Lipton Offers Thoughts for Boards of Directors in 2019” (December 2018), http://clsbluesky.law.Columbia.edu/2018/12/20wachtell-lipton-offers-thoughts-for-Boards-of-Directors-in-2019/.

- 19. Section 122 of the Canada Business Corporations Act, as amended by Bill C-97, Budget Implementation Act, which received Royal Assent on June 21, 2019 states that a board, when evaluating a company's “best interests,” may consider, among other things: “(i) the interests of shareholders, employees, retirees, pensioners, creditors, consumers and government, (ii) the environment, and (iii) the long-term interests of the corporation.”

- 20. CSA Staff Notice, supra, note 6, p. 34.

- 21. For Canadian public companies, the CSA Staff Notice describes the risk typology as: litigation, physical, regulatory, reputation, and business model. Supra, note 6, at p. 8.

- 22. TCFD Final Report, supra, note 4.

- 23. Ibid.

- 24. The CSA also recommends that companies do the same type of analysis: short, medium, and long term. See, CSA Staff Notice, supra, note 6, at p. 35.

- 25. Flavelle, Christopher, “Corporate America Gets Ready to Monetize Climate Change” (January 22, 2019), https://bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-22/muggy-disney-parks-downed-at-t-towers-firms-tally-climate-risk.

- 26. Ibid.

- 27. LEED is the acronym for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, a certification program established by the U.S. Green Building Council for optimizing a building's sustainability related efficiencies.

- 28. Sometimes, rather than “upstream” or “downstream,” the terms used are Scope 1 emissions, Scope 2 emissions, or Scope 3 emissions, categories which derive from the GHG Protocol adopted by the World Resources Institute and the World Business Council. Scope 1 means all direct GHG emissions; Scope 2 means indirect GHG emissions from consumption of purchased electricity, heat, or steam; and Scope 3 means other indirect emissions not covered in Scope 2 that occur in the company's value chain, including both upstream and downstream emissions. These might include: the extraction and production of purchased materials and fuels, transport-related activities in vehicles not owned or controlled by the company, electricity-related activities, outsourced activities, and waste disposal.

- 29. For example, in a landmark decision in February 2019, the New South Wales Land and Environment Court refused to approve the construction of a new coal mine based, in part, on the Court's view that the construction and operation of the mine, and the transportation and combustion of coal from the mine, would result in the emission of GHG's, which would contribute to climate change. The Court considered Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions for this purpose: Gloucester Resources Limited v. Minister for Planning [2019] NSWLEC 7. The decision was not appealed.

- 30. Litigation risk was identified as a separate risk in the TCFD recommendations. See, for example, Carney, supra, note 3, TCFD Final Report, supra, note 4 and “The New Horizon,” supra, note 5.

- 31. Heede, R. “Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854-2010,” Climatic Change, vol. 122, no. 1–2, pp. 229–241, 2014.

- 32. Climate Accountability Institute, “Press Release on Update of the Carbon Majors Project” (18 August 2018), http;//www.climateaccountability.org/pdf/PressRelease%20Manilia%20Aug18.pdf.

- 33. Ekwurzel, B., Boneham, J., Dalton, M.W., Heede, R., Mera, R.J., Allen, M.R., and Frumhoff, P.C., “The rise in global atmospheric CO2, surface temperature, and sea level emissions traced to major carbon producers,” Climate Change, vol. 144, no. 4, pp. 579–590, 2017.

- 34. There is similar litigation in Germany. There, a Peruvian farmer brought a nuisance action in 2015 against electricity producer RWE AG (a Carbon Major), seeking recovery of a portion of the costs that he and others incurred to establish flood protections (from climate change–caused glacial lake flood risk). After a lower court dismissed the claim, an appeals court ruled in November 2017 that the claim is admissible, and it is in the evidentiary phase, including with respect to RWE's contributory share of the GHG emissions that contributed to the risk. Lliuya v. RWE AG. Case No. 2. 0 285/15 (Essen).

- 35. City of Oakland v. BP plc, Case 3:17-cv-06011-WHA.

- 36. Based on “Climate change litigation databases” (accessed September 1, 2019) maintained by Columbia University, Columbia Law School, Sabin Centre for Climate Change, in collaboration with Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer LLP, http://climatecasechart.com/ [“Climate Change Databases”].

- 37. Campbell, C. “Burnaby mayor asks premier for the right to sue fossil fuel companies” (February 28, 2019), https://www.vancourier.com/burnaby-mayor-asks-premier-for-the-right-to-sue-fossil-fuel-companies-1.23649724.

- 38. Savage, Karen, “Toronto Lawmaker Launches Bid to Consider Climate Suit vs. Oil Companies,” https://www.climateliabilitynews.org/2019/03/22/toronto-climate-liability-lawsuit/.

- 39. In Australia, a claim was settled against the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, and a number of lawsuits have been brought in the U.S. against Exxon Mobil and Peabody Energy.

- 40. People of the State of New York v. Exxon Mobil Corporation, 452044/2018, N.Y. Sup. Ct.

- 41. This allegedly resulted in cash flow projections for the Alberta oil sands being understated by US$30 billion.

- 42. For example, in August 2019, a shareholder filed a lawsuit against Exxon's board members and executive officers on the basis of similar allegations, asserting breach of fiduciary duty and waste of corporate assets. Saratoga Advantage Trust Energy & Basic Materials Portfolio v. Woods, No. 3:19-cv 16380 (D.N.J).

- 43. York County v. Rambo (PG&E case), 3:19-cv-00994, N.D. Cal, and Barnes v. Edison International, 2:18-cv-09690, C.D. Cal.

- 44. Climate Change Databases, supra, note 34 (last accessed September 1, 2019).

- 45. Williams, C., and Routliff, J. “Disclosure of Information Concerning Climate Change: Liability Risks and Opportunities,” 2017, https://hennickcentre.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/CCLI-Disclosure-Paper-October-30.pdf.

- 46. Such as buildings, roads, ice roads, bridges, runways, railways, energy production and distribution systems, dams and water management systems, mining tailings ponds, stormwater and wastewater systems, transportation systems, and telecommunications.

- 47. See, for example, Adler, D. “Turning the Tide in Coastal and Riverine Energy Infrastructure Adaptation: Can an Emerging Wave of Litigation Advance Preparation for Climate Change?” 4 Oil and Gas, Natural Resources and Energy Journal, 519 (2018), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/onej/vol4/iss4/2.

- 48. Saratoga, supra, note 42.

- 49. For example, see Section 122 of the Canada Business Corporations Act, RSC 1985, c. C-44, as amended.

- 50. BCE, Peoples Department Stores, supra, note 17.

- 51. TCFD Final Report, supra, note 4 at p. 6.

- 52. Flavelle, supra, note 24.

- 53. TCFD Final Report supra, note 4 at p. 7

- 54. Ibid.

- 55. Including at least a 2°Celsius global warming scenario.

- 56. Mazzacurati, E., Firth T., and Venturini, S., “Advancing TCFD Guidance on Physical Climate Risks and Opportunities,” https://gca.org/global-commission-on-adaptation.

- 57. Lenders and insurers may also request these reports on infrastructure. For example, Infrastructure Canada has adopted guidelines which prescribe these assessments as condition to obtaining finance under certain federal programs.

- 58. The most well-known are the IEA transition scenarios, which model six different assumed pathways and associated temperature increases. For modeling physical risks, the IPCC's four Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) fix greenhouse gas emissions and analyze the resulting change to the climate.

- 59. For a recent discussion, see TCFD 2019 Status Report, supra, note5.

- 60. Final Report, supra, note 9.

- 61. The CSA noted that issuers advised that they considered this risk to be the most immediate (in terms of current impact) and tangible (as to actual costs and rates that issuers are incurring or expect to incur). CSA Staff Notice, supra, note 6, at p. 13.

- 62. See, for example, Securities Act (Ontario), R.S.O. 1990, c. S5, as amended, Form 51-102 F2 at Part (1) e.

- 63. Canadian Securities Administrators, “CSA Staff Notice 51-333: Environment Reporting Guidance” (2010), https://www.osc.gov.on.ca/documents/en/Securities-Category5/csa_20101027_51-333_environmental-reporting.pdf.

- 64. CSA Staff Notice, supra, note 6.

- 65. Ibid. at p. 37.

- 66. Canadian Securities Administrators, “CSA Staff Notice 51-358: Reporting of Climate Change-related Risks” (2019), https://www.osc.gov.on.ca/en/SecuritiesLaw_csa_20190801_51-358_reporting-of-climate-change-related-risks.htm..

- 67. Ibid., p. 8. For more information on SASB' s ongoing work in this area, including its Framework and Materiality Map, see https://www.sasb.org/standards-overview/materiality-map/.

- 68. Ibid., p. 9

- 69. Public companies in Canada typically make sustainability, corporate social responsibility, and climate action and resilience reports available on SEDAR.

- 70. The SASB standards can be used to support the implementation of the TCFD recommendation as they provide industry-specific metrics for use in TCFD disclosures.

- 71. “Investing in the Middle Class: Budget 2019” (March 2019), https://www.budget.gc.ca., at p. 330.

- 72. A New Horizon, supra, note 5 at p. 4.

- 73. Final Report, supra, note 9.

- 74. Unlike Canadian securities laws, however, TCFD recommends that organizations that omit a recommended disclosure should disclose their rationale for doing so.

- 75. For companies in the agriculture/food business, TCFD also recommends a scenario analysis assuming a major disruption hypothesis.

- 76. The TCFD also maintains a regularly updated resource website, known as TCFD Knowledge Hub, at https://www.tcfdhub.org.

- 77. See, for example, Part XXII of the Securities Act (Ontario). Securities regulators also have broad public interest powers, including the power to compel a company to make or amend disclosure, which could include disclosure of material climate change–related information in continuous disclosure documents.

- 78. See, for example, Part XXIII of the Securities Act (Ontario).

- 79. A slightly different definition will apply if the company is an investment company.