4

CEO Succession: Lessons from the Trenches for Directors:

Mark B. Nadler

Nadler Advisory Services LLC

Introduction

Let's start with the good news: Many businesses are doing a significantly better job than they used to when it comes to the all-important job of selecting a new chief executive officer. As boards have become more active and engaged over the past 10 to 15 years, the scales have clearly tipped in favor of a more professional, objective, and transparent succession process owned by the board rather than by the incumbent CEO.

However, before we declare “mission accomplished,” let's pause for a brief reality check. It's nice to think that boards have finally accepted their role as the ultimate owners of the succession process; yet, in the years and months leading up to the final vote on a new CEO, too many boards still look like an absentee landlord.

The good news is that the underlying approach to the succession process has changed faster and more dramatically than anyone would have predicted. Today, the great majority of directors agree—at least in principle—that boards should abandon the traditional succession model: an autocratic CEO orchestrating the selection of a personal favorite who demonstrates some combination of ill-defined qualities that somehow constitute “the right stuff.” Unfortunately, the old model persists in some form at far too many companies. We should remain highly skeptical of descriptions of the contemporary succession process as a meticulously planned, precisely executed, data-driven exercise in corporate precision—which it most assuredly is not.

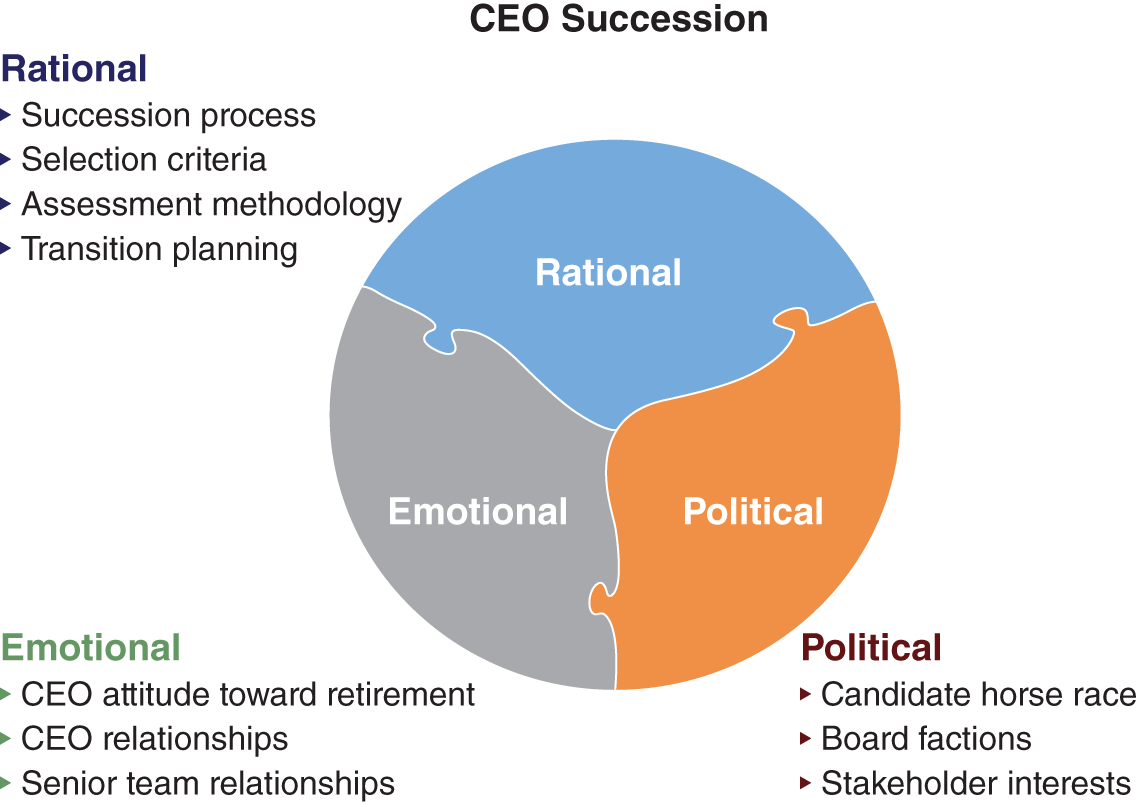

Our purpose here is to focus on the reality of succession, rather than the theory, and to examine how and why the succession process derails in real life. It boils down to this: No matter how hard you try to sanitize succession and turn it into an antiseptic, highly engineered, easily replicable process based on the science of talent assessment, it remains first and foremost an essentially human endeavor—often messy, inherently complex, always situation specific. And it always involves the inherent interplay of these three powerful dynamics (see Exhibit 4.1).

- Emotional: Personal emotion pervades the CEO succession process from start to finish, starting with those CEOs who struggle with the inevitability of retirement. Personal emotions shape the behavior of everyone involved: the reluctant CEO; the directors who are torn between loyalty to a longtime leader and the understanding that it's time for a change; the ambitious CEO candidates, competing in a winner-take-all contest; and the CEO's steadfast subordinates who view a change at the top with deep anxiety, and with good reason. All are buffeted by profound emotions throughout the entire process, continuing through the selection decision, the logistics of the hand-off, and the CEO's post-retirement role.

- Political: CEO succession stimulates unique political interest. Internal groups and outside interests all feel a personal stake in the outcome and its implications for the organization's future: which strategies to pursue, what level of wealth to return to shareholders, what kind of workplace to maintain for employees, and what role to play in the larger society. Political activity can be found within the board, among the candidates, across the employee population and, with growing frequency, among activist shareholders.

EXHIBIT 4.1 The Dimensions of CEO Succession

- Rational: This dynamic has gained unprecedented importance in recent years. It represents the opposite of simply finding a candidate with “the right stuff.” It embodies a logical sequence of steps, each delegated to a particular group or individual with explicit roles and responsibilities, with heavy emphasis on dispassionate assessment of candidates based on a consistent set of objective criteria. It envisions a process owned by the board and conscientiously assisted from start to finish by a willing CEO and management team responsible for identifying, assessing, and developing a robust set of qualified candidates.

Succession planning often runs aground when it ignores the inevitable interactions of all three dimensions. Succession can lead to dismal results when it consists of an aging CEO choosing an ill-equipped but loyal retainer to maintain the status quo; conversely, it can also produce unforeseen outcomes, ranging from bad choices to the loss of top talent to drawn-out disputes, when it places disproportionate importance on candidate-assessment technologies while ignoring political realities or personal relationships.

Over the years, we have identified 10 ways—some widely acknowledged, others discussed mainly behind closed doors—in which the succession process can stumble and fail. All can be avoided—or at least minimized—by carefully managing the delicate interplay of the rational, emotional, and political dynamics. They are:

- The talent disconnect

- The reluctant retiree

- The absence of human resources

- The assessment tool obsession

- The irrelevant criteria

- The cultural conundrum

- The mysterious talent pool

- The never-ending transition

- The forever CEO

- The persistent myth: It's just for the big guys

The Talent Disconnect

Looking at CEO succession trends over the past decade or so, two contradictory themes stand out. First, companies have become more likely to select their CEOs from among their homegrown talent—which in many ways should be a good thing. The second trend is that many companies still do a poor job of developing future CEOs. As the first trend line heads upward, and the second remains flat, the growing gap between the two represents the increasing risk of companies appointing ill-prepared CEOs.

The relatively recent trend toward internal promotion marks a sharp departure from previous decades. From the 1970s through the early 2000s, there was a general increase in the preference for outsiders, who at one point made up about a third of CEO selections. But in the United States—particularly since the Great Recession—there has been an overall steep decline in outside hires. The publication Strategy & in its annual study of CEO transitions found that 80 percent of all new CEOs at U.S. and Canadian companies in 2014 were promoted internally, a percentage that remained fairly constant through 2016. Both the Conference Board and search firm Spencer Stuart reported a dramatic uptick in outside CEO hires in 2017, but it remains to be seen if that was merely a one-time blip caused by major upheavals in retail and manufacturing.

Some companies have enormous confidence in their ability to develop top leaders, but there's evidence that confidence might be misplaced. In a 2014 Stanford University study, half the directors surveyed thought their company had an effective succession plan, yet only one in four felt they had enough qualified candidates lined up for the CEO and other C-suite roles—which begs the question of how those directors defined an effective succession plan. More specifically, Stanford reported that 39 percent of companies do not have a single internal candidate who they consider ready to step into the CEO role, and just over half—only 54 percent—are actively grooming someone for the role.

There's plenty of evidence that far too many boards remain distanced from the executive talent development process until an imminent succession demands their attention. By then, it's often too late for them to have much impact or to insist on the development of more than one credible candidate. Consider this:

- Only 46 percent of the directors in the 2014 Stanford survey said their board was actively involved in succession planning and talent reviews for top executive positions.

- Just over 40 percent in the same survey were not aware of any talent development programs for the top executives reporting to their CEO.

- In a Spencer Stuart study the same year, only 60 percent of respondents said they had a formal process for reviewing internal succession—which suggests that more than 40 percent didn't.

- Three years later, a National Association of Corporate Directors report came up with the same conclusion: Only 60 percent of directors said their boards had discussed long-term CEO succession in the past 12 months, and only 39 percent had identified a pipeline of internal candidates.

- In a 2018 survey by search firm Egon Zehnder, only 44 percent of CEOs said their own appointment had been part of a planned, formal succession process, and only 32 percent said they currently had any succession planning of their own underway.

There's a stubborn consistency in those numbers. Going back to research we did with the University of Southern California's Center for Effective Organizations nearly 12 years ago, and continuing through the most current studies, the percentage of companies with an informal, inadequate, or nonexistent succession planning process remains stuck at around 40 percent. Yet, as we noted earlier, the other important number is 80 percent—the proportion of CEOs being selected from within (up until 2017). And therein lies the disconnect: If the boards at 80 percent of companies have been promoting inside talent, but directors at 40 percent of companies have been dissatisfied or disengaged from talent development and don't think there's a single qualified internal candidate, the only conclusion is that a lot of boards continue to appoint CEOs they either really don't know or don't see as fully qualified.

The Reluctant Retiree

The disconnect between the rising rate of internal promotions and the lagging process in talent development falls squarely within the rational dimension of succession planning; it's a process failure. But that process lapse often can be traced to emotional and political factors—more specifically, to the incumbent CEO's reluctance or even outright refusal to talk about succession. Some reasons are obvious, others less so.

- Many longtime CEOs, particularly founders, simply cannot envision giving up leadership of an organization with which they've become so closely associated. The job becomes such an indelible element of the CEO's personal identity that the idea of somehow separating them becomes unthinkable.

- In the absence of mandatory retirement, some CEOs do everything possible to avoid confronting the inevitability of personal and professional mortality.

- Some CEOs mistakenly view succession planning as a distraction from their “real job.” We've seen that dynamic at work in several software and energy firms—all Fortune 500 companies—resulting in situations where CEOs between 8 and 10 years into their terms had no obvious successor in place and no interest in planning for one.

- Finally, there's the oft-cited excuse that the CEO wants to avoid launching a dysfunctional horse race among potential candidates. That objection mistakenly assumes that executives aren't already thinking ahead, planning their options, and positioning themselves to move up, hang on, or move away.

Fortunately, the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2009 made it much more difficult for CEOs to keep succession in limbo by deciding that shareholders could legitimately demand that boards disclose the essence, if not the details, of their CEO succession plans. Suddenly, boards realized that they could be held publicly accountable for failing to ensure a process was in place. That provided the impetus many of them needed to initiate the sometimes painful discussions with reluctant CEOs.

But the emotional and political dynamics that sometimes make those conversations so difficult really haven't changed. We worked with directors who felt they were either stonewalled or bullied by their CEO whenever they tried to raise the topic. At one leading manufacturing company, the CEO would angrily threaten to resign every time the board tried to discuss succession. The CEO at a high-tech firm would fume and pout for weeks any time directors mentioned succession; they finally tried to entice him with the offer of a substantial bonus if he made significant progress in succession planning. That simply resulted in a pitched battle at the end of the year over whether he had done enough to earn the bonus.

The SEC ruling didn't make these succession discussions any easier; it just made them necessary. And that places a new burden on nonexecutive chairs and lead directors to have the courage, sensitivity, and political savvy to know how and when to raise the topic and then to follow through.

The Absence of Human Resources

In the best succession processes, there are three key players: the independent leader of the board (either the nonexecutive chairman or lead director); the incumbent CEO; and the chief human resources officer (CHRO). Yet, all too often, the CHRO is essentially AWOL—either invisible or ineffectual. The absence of an influential, strategically minded CHRO who not only designs and manages an effective process, but who can also provide a trusted link between the CEO and the board, can be catastrophic.

In 2014, with the support of the National Association of Corporate Directors, we surveyed corporate directors (half of the respondents chaired their board's compensation committee) to better understand directors' perceptions of the CHRO. Overall, the results were sobering for HR leaders; only 31 percent of the directors said their CHRO had “a good or great deal of influence” on their board's decisions, and nearly a quarter said the CHRO had almost none at all. And the results regarding CEO succession—an area where you would expect the CHRO to be deeply involved—were particularly disturbing.

Overall, only 37 percent of the directors said their CHRO contributed good or very good value to the CEO succession process. We asked specifically about the CHRO's contribution to 10 different components of the succession process; the highest rating—only 47 percent received a positive score—was for providing objective candidate assessments, including the use of outside resources. (Once again, we're talking about the rational aspects of the process.) The lowest scores involved the emotional and political aspects of the process—only 30 percent rated “good or very good” for creating the profile of the future CEO (which is about as personal as it gets for the departing CEO and as political as it gets for the board), and for “personal counseling to the CEO on emotional aspects of succession and transition.”

The CHRO's role in succession is the ultimate test of how well they have earned the trust of both the CEO and the board, which is no mean feat. We worked with a Fortune 500 board that so thoroughly perceived the CHRO as nothing more than a flunky to the CEO—who was aggressively resisting retirement—that the board simply excluded him from the entire process. The CHRO spent the year sitting on the sidelines, criticizing the process to anyone who would listen. At the other extreme, we saw a very adept lead director persuade the CHRO that because of her unique, longstanding relationship with the CEO, it was time for her to “climb down out of the bleachers and get out on the field” to persuade him it was time to drop his resistance to succession planning. That delicate maneuver successfully ended a stalemate that could have continued for years.

The Assessment Tool Obsession

The dramatic swing of the pendulum toward the rational dimension of succession is most evident in the booming success of the talent-assessment industry, and its inroads at the CEO candidate level. All sorts of businesses, including the traditional executive search firms that are constantly seeking new revenue streams, have seized on branded assessment tools and methodologies in pursuit of competitive advantage. All sorts of claims are made for the statistical validity and predictive value of cleverly packaged tests and assessment reports.

Having used and observed a sampling of these tools and techniques over the years, here's our best advice: Don't fall in love with any of them. If someone had actually come up with a foolproof test that could consistently predict CEO success, we would all be using it by now. There's a reason you've never heard of that test.

Many assessment approaches have real value; all have limitations, depending upon how they're used. Some personal observations:

- There are some very impressive standardized tests of cognitive ability, emotional maturity, and personality tendencies, based upon extensive databases built over years of testing. The problem is that only a fraction of the data specifically refers to candidates for the CEO role, which is truly unique. In many cases, the findings are thoroughly documented, impressively presented, but somewhat irrelevant.

- Many of the tests are self-assessments, which often provide surprisingly insightful results; the Hogan Leadership Profile, for example (which combines the data from three of the online tools administered by Hogan Assessment Systems), is a particularly useful, well-validated tool. But at the end of the day, they're still self-assessments; their best use is as just one element in a multisource assessment, and as a way to raise red flags for deeper investigation and targeted questioning during other interviews.

- Some firms have popularized assessments consisting solely of a lengthy “behavioral interview” with the candidate. On the basis of that single interview—which can certainly be quite rigorous—the assessor provides a detailed evaluation of the candidate's strengths and weaknesses. The advantages are speed, simplicity, and cost, which makes them particularly popular in the private equity (PE) world. But over time, there have been growing concerns—including among some PE firms—that the overwhelming reliance on a single source of information can produce results of questionable value.

- Some firms offer branded assessment tools that convert subjective feedback into numerical ratings, in what sometimes borders on an adventure in pseudoscience. Assuming well-qualified people have conducted effective interviews with the right people, these findings can certainly provide valuable insights regarding relative strengths and weaknesses. However, declaring one candidate better qualified because he or she was rated a 5.6 on team building, using a 7-point scale, while another rated only 5.5 can be truly misleading, if not ludicrous. Having participated in those sorts of ratings for years, there is scant scientific validity underlying the decimal point distinctions between candidates; the ratings are often the result of assumptions, generalizations, speculation, and compromises among members of the assessment team (and, at times, between the team and the client). Contrary to outward appearances, there is nothing empirical about these numbers.

Bottom line: There is no shortcut or foolproof tool for evaluating CEO candidates. A meaningful assessment requires a variety of tools and activities that gather information from a broad range of sources. That preference was clearly expressed by the 220 chief HR officers who responded to a 2014 survey on CEO assessment by the Darla Moore School of Business at the University of South Carolina.

Over 75 percent of the respondents favored using multiple sources of data—and by overwhelming margins, those included analysis of past performance and 360-degree interviews for internal candidates and reference checks for outsiders. A much lower number—just over 19 percent—cited the behavioral interviews favored by PE firms as among the most effective techniques. Only 11 percent gave high ratings to cognitive ability tests, and just under 5 percent for business simulations, as assessment techniques for CEO candidates.

The Irrelevant Criteria

Of course, the value of any assessment is limited by the relevance of what's being assessed. We were approached once by the chief talent officer of a global communications company about coaching an internal CEO candidate. Each candidate had already been assessed by an outside firm. Unfortunately, each had been assessed on how well they were doing their current job, because the CEO—a classic case of the reluctant retiree—refused to involve the board in developing a role description for the next CEO. So the assessments weren't of much use in preparing candidates for the CEO position.

The absence of forward-looking criteria—clearly defined, prioritized requirements regarding the experience, skills, leadership qualities, and personal attributes the next CEO will need to successfully meet the anticipated strategic challenges—is where so many succession processes plunge off the tracks. While the idea that those criteria are necessary and should be developed with significant board input has gained broader acceptance, emotional and political forces are still very much in play in the form of highly subjective, quirky, and biased criteria that don't show up in the written role descriptions. Here are some examples we've encountered:

- The cloning exercise: At successful companies, it's not uncommon for succession planning to become a search for a carbon copy of the current CEO. Some boards seek comfort in continuing what they're used to; some CEOs see the choice as validation. The decision is rarely explicit, but the telltale sign is when the assessment criteria provide a perfect description of the incumbent on his or her best day, including management style, technical background, and personal strengths. That misguided approach ignores the fact that: (1) successful CEOs literally come in all shapes and sizes, and (2) the CEO's background and approach, which might have been ideal 10 or 20 years ago, could be wildly out of synch with the organization's future challenges.

- The unfair comparison: Directors tend to compare candidates with the current version of the incumbent CEO, which is inherently misleading; no one who has never held the job before can possibly come to the position as a fully formed, perfectly prepared CEO. A more useful point of comparison would be the incumbent CEO on his or her first day on the job.

- “The kids aren't ready”: A particularly insidious emotional force involves longtime CEOs who can't accept that their heir apparent will ever be ready for the job. The successor becomes frozen in the CEO's mind as a perpetual adolescent who will never reach adulthood. We worked with a board whose CEO had started and led the company for 20 years with the help of two younger, loyal subordinates. When the board finally insisted to the CEO that it was time to retire, he stunned everyone by aggressively lobbying not for either of his lieutenants but, instead, for the CEO of a competing firm. He simply couldn't bring himself to think of either of “the boys” (each around 50 years old) filling his shoes. (The board disagreed.)

- Personal preferences: Quirky criteria abound, grounded in history, tradition, culture, or individual bias. At one manufacturing company, the incumbent CEO wanted to disqualify the most obvious internal candidate because his wife, who apparently had a bit too much to drink at a company offsite, struck the CEO as “trailer trash.” We worked with a Fortune 500 CEO—a marathon runner and fitness fanatic—who refused to consider an outstanding candidate unless he lost 20 pounds. At one national retailer, we worked with a promising candidate who was vetoed because he'd never played high school or college sports—a tradition set by the founding CEO. At a major Midwest marketing firm, only avid outdoorsmen were considered serious candidates, although the business had absolutely nothing to do with hunting, camping, or fishing. Another CEO vetoed a well-qualified candidate because on a business trip they'd taken together, the executive watched a movie and napped rather than working throughout the flight, as the CEO always did. The list goes on, illustrating the endless variety of personal biases and irrelevant considerations that can distort the assessment and selection process.

- Insiders versus outsiders: When polled, about half of directors say they prefer to find an internal CEO candidate while the other half say they have a completely open mind—all they care about is finding the best candidate. Perhaps, but whenever we start one of these processes, we can just about guarantee that at least one director—and usually more—is convinced that “there have to be better people at other companies than the ones we have around here.” It really doesn't matter how qualified the internal executives are; some directors simply illustrate the notion that “familiarity breeds contempt.” Conversely, others endorse the principle, “Better the devil you know than the one you don't.” At a certain level, the succession process involves the clash of those two clichés—and more often than not, familiarity trumps hope.

The point is that the board should have a clear understanding of its own personal biases—and those of the incumbent CEO—before articulating the criteria for the next CEO. Going into the process, there tend to be all sorts of assumptions—many of them unspoken—about where the company is going and what kind of leader it needs. From the outset, any implicit expectations need to be made explicit.

The Culture Conundrum

Another important bias that often colors the succession process involves organizational culture. In one sense, attention to culture fit is evidence of the growing influence of the rational dynamic. Cautionary tales abound of executives who were regarded as superstars at their previous companies and then crashed and burned as CEO at a new company where they were wildly out of sync with the culture.

But emotion and politics can easily distort perceptions of culture and its role in succession. Nearly every initial meeting we've had in recent years with a CEO or board to discuss succession has involved the warning, “We have the most unique culture you're ever going to find,” or “Culture plays a much bigger role here than at other companies.” It's the organizational version of Garrison Keillor's fictional Lake Wobegon, where every child is exceptional: When it comes to culture, every company is unique.

The problem comes when that opening statement is followed by some variation of, “Therefore, it would be impossible for an outsider to come in as CEO.” To be sure, there are situations where that might be true. But we would vigorously caution boards not to accept that assumption at face value.

When people lead with the importance of culture, the implication is that the organization shares some core beliefs about the way they do business and treat people—both inside and outside the organization—that are essential to their identity and worthy of maintaining at all costs. But there is often a fairly sizeable gap between the culture the company describes and the one it lives, between the culture the directors hear about in the boardroom and the culture that actually shapes behavior in the labs and offices and factories. Even at marginally successful companies, longtime CEOs and directors tend to view their culture through rose-colored glasses.

Boards often make two assumptions, both wrong: first, that the culture created by the founders is as relevant and robust as it was decades ago; and second, that the culture at the historic, geographic, and operational core of the company prevails throughout the organization. As companies grow through acquisitions, geographic expansion, and extension into new lines of business involving new people from different professional and technical backgrounds, the core culture can become frayed, transformed, even discarded, depending upon where you look. Complex companies invariably have a multitude of subcultures, often with some very different, even conflicting, attributes. All of this makes it difficult, even misleading, to talk about “The Culture.”

Several years ago, during our first meeting with the board of a major industrial company, the directors explained that the company's phenomenal growth was due to the culture instilled by the longtime CEO, who sat at the head of the table, nodding his agreement. They described the culture as a “true meritocracy” where everyone from the factory floor to the C-suite worked hard, was held accountable for their performance, and shared in the profits from the company's success.

The problem, we soon discovered, was that over the course of 20 years, the culture had atrophied. The young go-getters of the early days had been rewarded so well that they never left, resulting in an aging workforce, incredibly little turnover, and scarce opportunities to create attractive career paths to entice new recruits. The once-prized bonus had become taken for granted; it was viewed as an entitlement, not a motivator. The oft-repeated commitment to accountability became a growing source of cynicism as longtime members of the inner circle seemed to enjoy lifetime tenure regardless of slumping results. What's more, the company had expanded through several major acquisitions; by the time we showed up, over half the employees worked at heavily unionized sites, in sharp contrast with the core business, which had aggressively avoided unionization for decades. The culture described to us by the CEO and the board evoked smirks and eye rolls when we talked with managers at the unionized plants.

So, as we worked with the board to articulate their profile for the next CEO, we urged them to squarely confront the culture issue. It simply wasn't good enough for them to say, “It is the responsibility of the next CEO to maintain the unique culture which has made our company an industry leader”; they needed to step back and understand what had happened to their culture—to identify which elements to keep, which to fix, and which to replace. Only then could they have an intelligent conversation about whether their culture eliminated the viability of any outside candidates.

The Mysterious Talent Pool

A few years ago, we were asked to assess the senior executives of a well-known consumer magazine to help identify both near-term and future CEO candidates. In our presentation to the board, we described the young woman who headed the advertising sales team as the most promising long-term candidate, with outstanding potential. Some directors were bewildered. “If she's that great,” one asked the CEO, “how come we've never heard of her before?”

In hindsight, it's hard to know who was more at fault—the CEO for not providing the board with sufficient exposure to his entire team, or the board for not demanding it. Nevertheless, that situation was far from rare. A few years later, as we began the CEO succession process at a global software company, we asked each of the directors confidentially if they had any strong feelings about potential successors among the CEO's direct reports; over and over, directors would take a pass, admitting they really weren't familiar with the senior team.

It's worth asking why any board would allow itself to get into the position—either through the CEO's manipulation or through its own indifference—where it had so little visibility into the company's talent pool. And yet, that situation persists at far too many U.S. companies. The Conference Board and Stanford University found in 2014 that only 55 percent of directors said they understood the strengths and weaknesses of senior executives extremely well or very well. One third said they understood these strengths and weaknesses only moderately well, and over 11 percent admitted knowing those strengths and weaknesses only slightly well or not at all well.

In that same report, only two thirds of the directors said they'd gotten to know the full senior management team in a professional manner—by working with them on a project or engaging in discussion outside the boardroom. In reality, the great majority of interactions between directors and potential CEO candidates continue to take place during formal board presentations—a totally unnatural setting that sheds little light on the executive's true ability to manage and lead. And yet, search firm Spencer Stuart reports that's how 97 percent of boards get to know their internal candidates. Less than a third—only 31 percent—said their directors had regularly scheduled meetings outside the boardroom with the CEO's direct reports, and only 26 percent said their directors regularly visited company operating sites where they could interact with candidates in their natural environment.

The most extreme case, of course, was illustrated at Hewlett-Packard, where the board appointed an outside candidate who the majority of directors had never even met, much less gotten to know. With that situation very much in mind, the chairman of a community bank where we were helping with succession concluded that too few of his directors had spent sufficient time with the two internal candidates outside of formal board meetings. Accordingly, as the board neared its final decision on succession, he directed that with the CEO's help, each director was responsible for scheduling some one-on-one time with each of the candidates in an informal setting before he would allow the full board to begin its final selection discussion. It took a couple of months, but in the end it was well worth the investment of time.

The Never-Ending Transition

Just as some CEOs do everything in their power to block the launch of the succession process, some are just as determined to keep it from ending. Emotionally, the process comes to a head when the board formally selects the next CEO; then come decisions about the timing, logistics, and communication of the handoff. If the CEO has been resistant to retirement—either actively or passively—the scheduling of the handoff is where personal emotion can truly overwhelm the rational process.

In most situations, the period between the public announcement of a new CEO and the new leader's first official day on the job ought to last in the neighborhood of three months. That provides time for the incoming CEO to spend time—which will soon become scarce—getting out and about, both inside and outside the organization—meeting people, listening, learning, and developing ideas about immediate priorities. It allows for an orderly handoff while conveying a reassuring sense of stability.

Unfortunately, some CEOs keep trying to hang onto the job even after a successor is named or in place. For example, we've encountered situations such as these:

- The CEO of a large regional bank, who spent a year transitioning his daily responsibilities to his COO and heir apparent, suddenly announced to the board a week before the formal succession vote that he expected to be retained in office for yet another year, with full salary and benefits, so that he could take his victory lap with longtime customers at a series of company-organized parties and receptions in his honor. He proposed that his newly named successor manage the company on a daily basis for an additional 12 months before actually taking over. In a turbulent executive session the night before the full board meeting, the board's nonexecutive chairman and the chairman of its governance committee persuaded their fellow directors that enough was enough, that the incoming CEO wouldn't sit still for another year and shouldn't be asked to. The next morning, the board voted unanimously that the new CEO would take office—and the incumbent would depart—in two months.

- A 20-year CEO who had battled succession ceaselessly finally relented after his board lost patience with his threats and ultimatums. The board selected his successor at the end of August, with the intention of installing him as CEO on January 1. As January neared, the incumbent manufactured one crisis after another, finally persuading the board to postpone the transition until the April shareholders' meeting. By the time April arrived, the CEO had succeeded in undermining the board leadership and the transition was delayed yet again. The new CEO didn't officially take over until two years after the board chose him.

- At a nearly billion-dollar family-owned company, the chairman and CEO finally bowed to board pressure to name his successor, who would be named COO and gradually assume the CEO's duties. Once the successor was chosen, the incumbent announced the specifics of the transition plan—which is when it became clear that “gradually” meant a six-year transition.

Endless transitions are unhealthy for everyone involved. Sometimes, promising candidates lose patience and go somewhere else rather than subject themselves to an endless transition. The interim period can become frustrating for the departing CEO, as well. Some of the best CEOs we've worked with have told us that in hindsight, they wished they had negotiated shorter transitions. Once the new CEO is announced, one recalled, “it's like someone flicked the light switch. Just that quickly, all attention turns to the incoming CEO. All of a sudden, your phone stops ringing, and people are lined up outside their door, not yours. At a certain point, you're just in the way.”

The Forever CEO

The final phase of the succession process—and a continuing source of problems—comes after the official handoff. Some retired CEOs take too long to “leave the building”—either literally or figuratively. At one pharmaceutical firm, as the CEO got off the elevator each morning, he had to walk down a hushed, carpeted hallway past the office suites of three of his retired predecessors—a constant reminder of his limited influence.

While office space for the retired CEO can create nasty disputes more often than you might think, the more substantial issue is the former CEO's continued service on the board. Sitting in the boardroom, where the new CEO is just starting the long process of building trust and credibility with the directors, the predecessor can either play a supportive, low-key role or maneuver to maintain his or her influence.

Research into this phenomenon is limited but instructive: The presence of the previous incumbent at the head of the board table does in fact inhibit board support for the new CEO's attempts to break from the past. In a study of 181 high-tech companies, Donald Hambrick of the University of Pennsylvania and Timothy Quigley of Lehigh University found that 39 percent of CEOs who left office remained as board chair for at least one year, and 26 percent stayed on for at least three years. The presence of these so-called “shadow emperors,” they concluded, imposed either “implicit or explicit constraints” on the ability of the new CEO to substantially change their predecessor's “strategies and policies.” As a result, they found, new CEOs in these situations are generally more successful at avoiding major problems than in capitalizing on new opportunities.

The situation generally becomes most complicated when the former CEO is the chairman—but not always. At one insurance company, a retiring CEO got around the requirement that the chair be an independent director by demanding—and receiving—a seat on every board committee, affording him endless opportunities to undermine his successor. Perhaps the most extreme case was at Twitter in 2015, which found itself at one point with three of its former CEOs on its board, raising concerns during the search process about how a new CEO could possibly lead effectively with three predecessors sitting around the table.

But the outgoing CEO's continuation on the board is far from rare. Spencer Stuart's annual survey of the S&P 500 found in 2013 that 45 percent of departing CEOs remained on the board as chairman; by 2017, that percentage had risen to 57 percent. Sometimes their term is brief, but not always; the Conference Board found that 36 percent of CEOs remained on the board for two years following their resignation as CEO, and 26 percent remained for five years or more.

There are a couple of reasons why the trend is growing. First, with more boards promoting an insider with no CEO experience, they find it reassuring to keep the departing CEO around for some period as a sort of security blanket. Second, U.S. companies are moving slowly but surely toward separating the CEO and chairman roles—but it's much cleaner to split the roles as a new CEO as taking office, rather than stripping an incumbent of the title. Indeed, the Conference Board found reported in 2011 that 19 percent of newly appointed CEOs were also named chairman at the same time. By 2017, according to Spencer Stuart, that number had dropped to only 7 percent.

There's nothing wrong with an orderly transition in which the former CEO helps to sustain a sense of continuity; best practice suggests something in the range of 6 to 12 months. The issue for boards is to carefully think through the particular circumstances of each transition—the factors leading to the CEO's retirement, the relationship between the old and new CEO, the board's expectations regarding the scope, depth, and urgency of changes they want the new CEO to introduce—and to plan the outgoing CEO's role accordingly.

The Persistent Myth: It's Just for the Big Guys

Once, at a directors' meeting in Houston, we mentioned that many CEOs avoid succession planning for fear of launching a horse race among potential candidates. A director stood up and said, “I wish we had that problem. Most of us are lucky if we have even one inside candidate!” The rest of the audience laughed appreciatively.

Both research and our own experience suggest that too many boards think of formal, rigorous succession planning as something that only applies to big companies. It isn't; the gold standard of succession planning we've personally encountered was at a small community bank in central Michigan with only a few hundred employees. Nevertheless, there's little question that bigger companies are more likely to engage in long-term succession and to spend more time and effort planning for it.

The NACD found in 2014 that big public companies are twice as likely as small ones to identify CEO succession as a board priority and rank it as a higher priority: It tied for third among big company directors, but only sixth at small companies. Only 30 percent of small companies were found to have a formal succession planning process (compared with nearly 80% of big companies); about half of the small companies (49%) handle succession through informal board discussions; and one in five have little or no board involvement at all in succession planning until it's time to actually vote on the new CEO. We should keep those numbers in mind before congratulating ourselves on all the progress that's been made in recent years.

Our own experience shows that a clear purpose and aligned leaders outweigh company size when it comes to handling succession well, as demonstrated by Isabella Bank Corp. A community bank with less than $2 billion in assets, Isabella is based in Mt. Pleasant, MI (population: 26,185), the home of Central Michigan University, and the heart of a largely agricultural region far from Detroit. Isabella has been content to remain reasonably small, to grow slowly and with great care, and to stay focused on its local customers and communities.

Rick Barz, a lifelong employee, recalls that shortly after he was promoted to CEO in 2006, “We did a reality check that revealed that six or seven years down the road, seven of our most senior executives—myself included—were going to retire within a three-year period. We had built a really strong culture, one that we wanted to preserve, and to do that we would have to hire from within.… So we began to work on the criteria we would be looking for in those top jobs, starting with the CEO position. And as I thought about all the development we needed, I realized I couldn't do it myself—we needed outside help.”

So, with the full support of board chairman Dave Maness, and with CHRO Dan Ebersole playing a central role, Barz launched a long-term effort to identify, evaluate, and develop internal talent. For a bank of that size, bringing in a locally based talent development consultant was a significant expense, and the timing was bad. “This was happening when the economy was on its back, and it was a big, big expense,” Barz remembers. “But the alternative would have been much more expensive—either going to the outside, or putting internal people in jobs they weren't prepared for.”

The board was involved from the very start, and as the process turned to CEO succession, the chairman took the lead. About two years before the CEO was scheduled to retire, Maness decided to enlist professional help with the final stage of the succession planning process, and engaged the leadership consulting group at one of the major search firms (which is when we got involved). It was another major expense for the small company—but entirely consistent with Maness's strategic vision for the bank.

“One of my biggest concerns as chairman, as I look at our future, is making sure we have the right talent to run this place,” says Maness. “Maybe it's a bigger concern for us because we're in a rural area, and we don't have all this talent swimming around; it's not like there are 30 other banks where we can go and poach talent. I don't view talent development as a luxury. We're independent, we want to stay independent, we want to be an asset for our community for a long time. For that to succeed, you have to plan long term.”

With Maness leading the process—and with the CEO and CHRO deeply involved every step of the way—the board established a formal procedure for working with the consultants to develop the assessment criteria for the next CEO, evaluate the internal candidates, and consider whether to look outside (which they decided against). With a year to go before the CEO's retirement, two finalists were selected and assigned to new leadership roles where they could grow professionally, assure the board of their readiness to move up, and begin to fashion a working relationship of their own, which eventually became an enormous benefit once they were promoted to the top executive positions.

The overall process—starting with the initial talent development program, and continuing through the assessment process and transition planning—was well-organized and efficiently executed. But the formal plan succeeded because the key leaders never lost sight of the importance of personal emotions and complex relationships—between the CEO and the chairman, between the candidates and the board, and within the management team, which included several executives who were disappointed to learn that they wouldn't be getting the top job.

“You have to be able to talk about these things,” says Maness, who was widely credited with demonstrating tremendous sensitivity in helping the board and management navigate the process. “You have to be able to have these hard conversations. I think we've been able to do that because we've had a group of people who always understood that it's not about us, it's about the institution, and you always have to remember that. It's also just the way Rick did things, and part of the culture. When you see a tough problem, you don't hide it or put it off—you face it, and you take care of it, because it's not going to go away.”

Conclusion

The approach Dave Maness describes above might just be the most valuable best practice of all, regardless of company size. At the end of the day, courage, candor, and common sense lie at the heart of effective CEO succession. Planning is critical, tools and methodologies are important. But in the final analysis, successful transitions rest upon the ability of proud and powerful business professionals to have these essential, hard conversations each step of the way.

About the Author

Mark B. Nadler is principal of Nadler Advisory Services, a consultancy specializing in board effectiveness and CEO succession. He has consulted to organizations of all sizes across a broad range of industries, ranging from Fortune 500 corporations and private equity portfolio companies to family-owned businesses and professional associations.

Mr. Nadler co-founded Nadler Advisory Services with his brother, David Nadler, in 2014, following several years as a partner in the Leadership Consulting Practice of Heidrick & Struggles. Prior to that, he was a partner for 16 years at Delta Consulting Group (later Mercer Delta and Oliver Wyman Delta), where he founded the global Strategic Communication practice and helped develop the corporate governance practice.

He has written or contributed to more than 70 publications related to leadership, governance, and organizational effectiveness, including three books with David Nadler—Building Better Boards: A Blueprint for Excellence in Governance (2006); Champions of Change (1998); and Competing by Design (1997). He authored “Beyond Best Practices: Revisiting the Board's Role in CEO Succession,” a chapter in Boardroom Realities (2009), edited by Jay Conger.

He is a frequent speaker on governance and succession before groups including the National Association of Corporate Directors, the Academy of Management, Wharton School's Corporate Governance Program, the University of Southern California's Corporate Governance Summit, the Bank Directors' Chairmen and CEO Forum, the Human Resources Planning Society, and the Society of Corporate Secretaries and Governance Professionals.

Prior to consulting, Mr. Nadler worked as a journalist and news executive. He was a senior editor at the Wall Street Journal and vice president/executive editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, and twice served as a juror for the Pulitzer Prizes in journalism.

References

- The Conference Board and Heidrick & Struggles. 2018. “CEO Succession Trends 2017.”

- Deloitte. 2014. “2014 Board Practices Report.” Society of Corporate Secretaries and Governance Professionals. Deloitte Center for Corporate Governance.

- Egon Zehnder. 2018. “The CEO: A Personal Reflection.” Egon Zehnder International, Inc.

- Favaro, Ken, Per-Ola Karlsson, and Gary L. Neilson. 2015. “2014 Study of CEOs, Governance and Success: The Value of Getting CEO Succession Right.” Strategy &, April 14.

- Larcker, David F., and Scott Saslow. 2014. 2014 Report on Senior Executive Succession Planning and Talent Development Survey. The Institute of Executive Development, Rock Center for Corporate Governance, Stanford University Graduate School of Business.

- Larcker, David F., Scott Saslow, and Brian Tayan. 2014. How Well Do Corporate Directors Know Senior Management?

- NACD. 2014. “NACD 2013–2014 Public Company Governance Survey.” National Association of Corporate Directors.

- NACD. 2017. “NACD 2016–2017 Public Company Governance Survey.” National Association of Corporate Directors.

- Nadler, Mark B. 2009. “Beyond Best Practices: Revisiting the Board's Role in CEO Succession.” In Boardroom Realities: Building Leaders Across Your Board, edited by Jay A. Conger (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass).

- Nadler, Mark B., and Julie J. Chen. 2015. “The HR Threat to Board Effectiveness.” NACD Directorship (July–August).

- Quigley, Timothy J., and Donald C. Hambrick, 2012. “When the Former CEO Stays on as Board Chair: Effects on Successor Discretion, Strategic Change, and Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 33: 834– 859.

- Spencer Stuart. 2014. Spencer Stuart Board Index.

- Spencer Stuart. 2018. Spencer Stuart 2017 Board Transitions.

- Wright, Patrick M., Anthony J. Nyberg, Donald J. Schepker, and Michael D. Ulrich. 2014. “2014 CEO Assessment and Onboarding.” Darla Moore School of Business, University of South Carolina.