44

Ensuring Good Governance and Business Success in International Subsidiaries

Thomas C. Sears BA MBA PhD

Retired Canadian Bank Executive

My phone rang. On the line was the senior vice president of one of my largest clients. In the six months since taking up my posting in London, we had become quite friendly. But this call was different. This normally very personable executive sounded like a father who had just lost a child. His tone was serious. He sounded stunned … not knowing what to do. “Tom,” he said, “we have just been told to put down our pencils and go home … every one of us.” His words have echoed with me over time, since that Friday morning. This is how I first learned of the greatest breach of corporate governance in history to that date.

Kevin's firm, the world's largest merchant bank, was founded in 1762 in London, England. By 1995 it had become one of the most powerful companies in international finance. Baring Brothers Bank was about to enter the corporate history books for all the wrong reasons.

Three years earlier, Nick Leeson was appointed to head up Barings' new derivatives and futures trading subsidiary in Singapore. Shortly after his arrival and unknown to others, Leeson started making unauthorized and speculative trades. These “bets” were initiated to cover a loss caused by an error on a client account. His brand-new subsidiary was going to have to cover that loss and it would reflect poorly on him as unit head. He decided to roll the dice to cover that loss, and he did. His speculative trading worked. With that success behind him he became hooked. His luck continued and in his first year he generated large profits for Barings and boosted the bank's bottom line by 10 percent. Leeson was the hero of Baring's newest international business venture. Leeson's bosses were pleased with their golden-haired boy who generated these huge profits for the bank, and equally large bonuses for the entire division including themselves. But the golden touch soon disappeared. Leeson's bets started to go wrong. To cover these new losses, he continued to double down. Losses grew exponentially. At the end of his second year, losses exceeded £2 million. His rogue trading was well hidden in a dummy client account. By year three losses ballooned to £208 million. When Leeson fled Singapore in February 1995, they had exploded to £827 million (US$1.4 billion), twice the bank's trading capital. The oldest and largest merchant bank in the world was bankrupt and would be sold to Dutch bank ING for £1.

International operations can bring great commercial success and even prestige to a company. But international operations bring new challenges and risks not previously encountered by even the most successful of domestic and international companies. These units not only need to be successful business ventures, they require effective corporate governance. Often located thousands of miles away from the head office, how do great companies achieve these two highly important and possibly competing goals of achieving business success within an environment of effective governance controls without either of these objectives interfering with the other?

It is well known by experienced business leaders and boards that the failure rate faced by new business ventures is high, particularly in the early years. According to Statistics Canada, “At least half of new companies in Canada go out of business before their third anniversary and only one-fifth of them survive a decade.” Other countries will have their own statistics, but the message is clear: The risk of failure is high for new business ventures. Similarly, successful domestic corporations face new and challenging risks when expanding into international markets. They can face different cultures, languages, and product preferences as well as unfamiliar regulatory systems and governments. While there are many wonderful success stories with international expansions, there are numerous cases of highly successful companies failing in foreign jurisdictions. Knowing this gives pause to cautious business leaders. Examples include Best Buy in China and Turkey; McDonald's in Brazil and Barbados; Canadian Tire in the United States; Starbucks in Australia; Target in Canada. Successful domestic companies failing outside of their home market are not rare. These companies often fail due to business, product, or cultural misjudgments based on inconsistencies from the home market. Decision makers have simply missed some material fact(s) during their due diligence to expand internationally.

But the prospect of growth, the lure of new markets, or expansion moves by competitors can entice even the most cautious of business leaders. International expansion can offer companies better access to resources, lower costs of manufacturing, increased sales, or to simply keep up with industry competition. Today's seamless communications, transportation, and technology give decision makers confidence to reach outside of their home and traditional markets to grow their bottom lines, diversify their corporate earnings, and strengthen their corporate sustainability. Successful companies do their homework and complete a rigorous due diligence process to understand the differences in new and unfamiliar markets and look to find ways to address the nuances of the new market before deciding to invest in a less familiar jurisdiction. To do otherwise can lead to the failure of the new venture and financial losses as outlined above.

However, “business” risks are not the only risks they will face. Failures of governance are another source of risk beyond business, product, or cultural challenges. Governance failings can cause irreparable harm to the corporation and its stakeholders, as it did for Barings.

Famous cases of corporate governance breaches involving an international subsidiary include ENRON's use of their Cayman subsidiary to hide losses that eventually brought that company down; ENRON's failure caused the subsequent demise of their external auditor, Arthur Andersen. AIG used its Bermuda subsidiary to fraudulently assist a client misrepresent their domestic profits. In this case AIG enticed reinsurance partner Cologne Re to aid in the fraud through Gen Re.'s Irish subsidiary. That governance breach resulted in extreme reputational damage to both companies, fines being issued, employees losing their jobs, and Wells notices being issued to arrest senior executives in these firms and bringing them to trial.

Other famous governance breaches involving international subsidiaries include:

- U.S. Bank JPMorgan's “London Whale” trading loss in 2012 is estimated at $5.8 billion. In the resultant investigation it was further alleged that JPMorgan London intentionally hid the transactions in question from British regulators.

- The UK's HSBC was found guilty of allowing Mexican drug cartels to launder billions of dollars through its U.S. subsidiary, resulting in a fine of $700 million.

- The UK's Barclays was found guilty of civil and criminal crimes in their U.S. subsidiary for manipulating the LIBOR rate (London Interbank Offered Rate) and fined $450 million.

Researching other examples of rogue traders, corrupt executives, and other breaches of governance in international operations that damaged the parent company is easy with the Internet. Simply search “International Corporate Fraud.” Board directors do not want their corporate names to appear when governance geeks or journalists do these searches.

With these concerns in mind, how should an international company set up and manage its foreign subsidiaries for both business success as well as effective corporate governance? Let us start after the point when business leaders in the parent organization have completed a very thorough due diligence on the “business” differences of the new jurisdiction that they need to address and have plans to mitigate the market nuances that brought failure to Best Buy, Target, and others mentioned earlier. With this confidence on the business side, we turn our attention to how parent organizations implement these successful business practices as well as instill effective governance in their international subsidiaries.

In my research on effective corporate governance of international subsidiaries, I identified the following five-step process for creating good corporate governance structures and practices within the subsidiary that work in alignment with the business practices and objectives.

Align the Purpose of the Subsidiary and Its Board to the Parent

International subsidiaries will have different purposes. Expanding your retail banking operations into a new country is quite different from opening a low-cost standalone operation to manufacture circuit boards that will serve as component parts for devices you will be selling further upstream, or compared to a subsidiary starting a local mining operation for an international mining firm. One seeks marketing success, another high-quality factory operations, and the third seeks efficient resource extraction. Board makeup and mandate will vary based on the subsidiary's purpose.

Geoffrey Kiel of Australian Catholic University developed a “Degree of Freedom Model” as a tool to help international business leaders examine the purpose of their subsidiary and the resulting impact on the board structure and mandate.

Kiel's model helps parent organizations decide how integrated an international subsidiary and its board must be to the parent. An international bank, for example, may require very close alignment of a subsidiary to the parent while such coordination might be less necessary for a standalone unit manufacturing circuit boards for computers or smartphones.

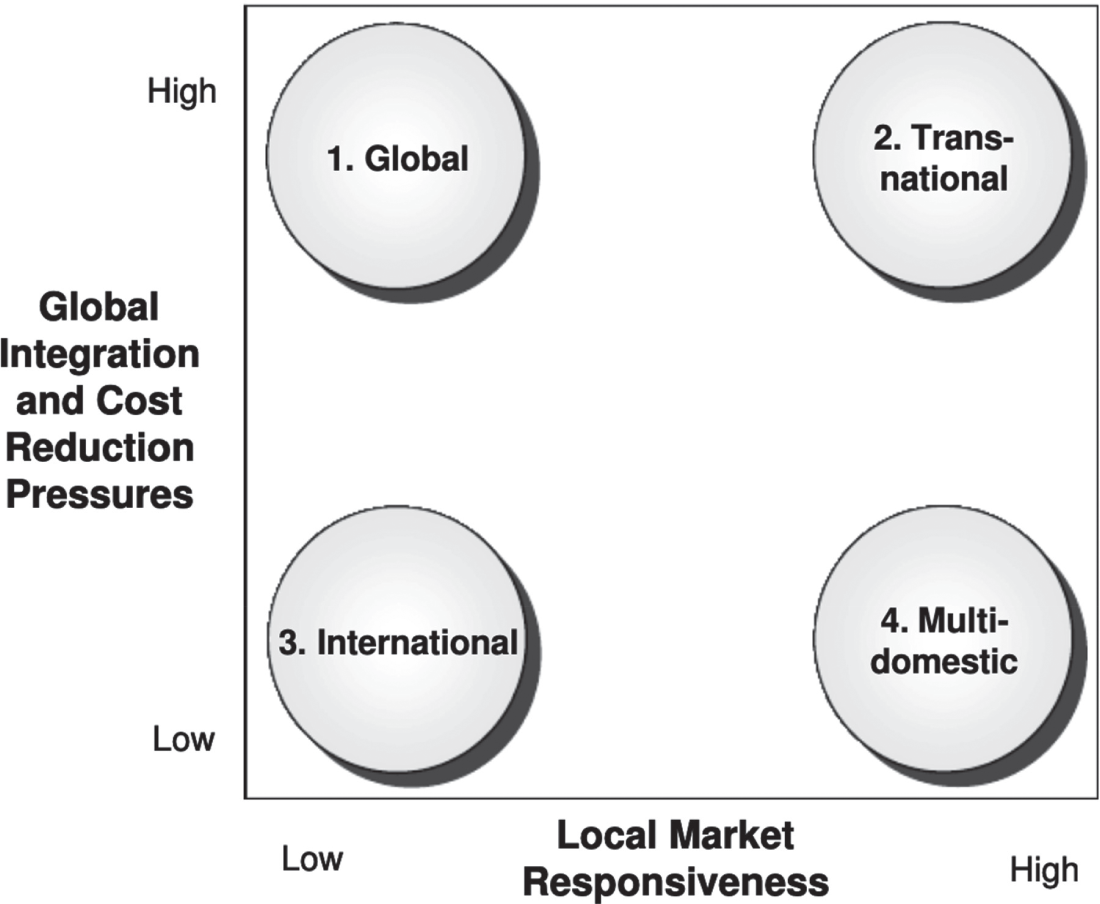

In this model the user first must determine whether the need for Global Integration and Cost Reduction Is High or Low for the international subsidiary, and then whether the need for Local Market Responsiveness Is High or Low. In so doing Kiel suggests the user will then determine which of four categories the subsidiary board best fits. Knowing this Degree of Freedom indicates how a subsidiary board should be structured and operated.

The “Global” Strategy is used when a subsidiary has a high need for Global Integration and Cost Reduction but is low in Local Market Responsiveness. The subsidiary board is operated by direct control of the parent. This would include our example of a subsidiary that manufactures circuit boards for the company's upstream smartphones or computers. It would be staffed by local managers who will ensure compliance with local laws, but the local board would be a legal compliance or puppet board controlled by the parent.

The “Transnational” Strategy is for a subsidiary that has high needs for both Global Integration and Cost Reduction as well as Local Market Responsiveness. In these circumstances the subsidiary board operates under dual reporting controls. This strategy requires the subsidiary board to provide a strong local representation for direct input on local strategies. As well, it requires effective representation of the parent's global need for control and oversight. This would include international banks that operate retail services locally.

The “International” Strategy points to a subsidiary where the needs for Global Integration and Cost Reduction Pressures and the needs for Local Market Responsiveness are both low. In these cases, the subsidiary board operates as an advisory board. Examples of this strategy might include international reinsurance operations that locate in a jurisdiction having special skills that exist in that location (e.g., reinsurance in Bermuda) or for some other favorable feature of that jurisdiction such as a low-tax advantage. The board is structured to support this business strategy of the parent with local people sought for their views or who might have specific local expertise or responsibilities, like law or finance. Subsidiary governance is conducted by the parent corporation and its internal management, similar to the “Direct Control” model.

The “Multi-Domestic” Strategy is used when the need for Local Market Responsiveness is high, but the need for Global Integration and Cost Reduction Pressures are low. The subsidiary board is a local board. This kind of board often fits large international companies like those in construction or mining where local market responsiveness is high and a significant amount of strategic decision-making is conducted at the subsidiary level. Kiel proposes that a “local board” is best, supported by management of the parent organization. The local subsidiary board has full control, performing all board roles and duties.

In each of these strategies, governance responsibilities for the parent organization are conducted by head office executives from the responsible business line of the parent company, usually by attending subsidiary board meetings. In the more critical or larger subsidiaries, other executives from the parent may also serve as directors on the subsidiary board and might include representatives from key control units such as the compliance, risk, finance, or the corporate secretarial department. This allows for direct oversight by the executives responsible for that business line, plus adds other independent oversight from the parent.

Align the Processes of the Subsidiary with the Needs for Good Governance

For more sensitive and larger subsidiaries, trusted and trained managers and employees from the parent office may be placed at various key levels in the subsidiary to provide additional strengths in day-to-day operating oversight and training, as well as bringing cultural affinity from the parent. These employees can serve as important conduits in a two-way communication between the subsidiary and the parent both formally and informally. Further, these trusted employees can assure internal auditors, risk officers, and compliance officers from the parent's home operations that the usual control processes, active in the parent's environment, are being mirrored in the subsidiary. This injection of skills and soft controls strengthens the daily governance of ongoing operations and makes any wondering local employee think twice about any irregular behavior. As the subsidiary matures, these responsibilities can be passed to local employees.

In the Barings case, Nick Leeson was an expat and the top person in Singapore. He controlled both the back office and the trading unit, a critical breach of the principle of the segregation of duties needed to ensure traders are working within their limits and mandates. Segregation of duties would have been of paramount importance to Barings but was bypassed in Singapore by Leeson. Local employees would not have known to whom to report Leeson's fraudulent acts.

It is also of critical importance that the subsidiary's executive directors from the parent company ensure that audits and other reviews, like risk and compliance checks, are regularly performed and that the company's usual controls in key areas of human activity are working effectively. As they do in the parent organization, these regular reviews do find errors and the existence of these checks also deters an agent in the subsidiary from considering any irregular activity. While it is easy to be swept away on the business issues facing management and the board, active and effective control mechanisms and processes are every executive's responsibility in ensuring good governance practices in the subsidiary. It is equally important to recognize and be prepared for employees in an international location feeling that these oversight mechanisms are imposing and detract from local business activities and objectives. It is of critical importance that these processes must be understood in the subsidiary as adding value to management, the employees, and the subsidiary board. It is the parent board's responsibility to ensure they are in place and effective, and not deferred as they were in Barings' case.

It can be expected that employees from the parent organization will not at the outset understand the nuances of the environment or culture that the subsidiary operates within. And it may well be that subsidiary employees are hesitant to embarrass their new employers by speaking up. Identifying mature local employees in the subsidiary who can serve as “cultural ambassadors” to the parent employees can alleviate that risk. Empowering local employees with this role tells all local employees that the parent cares about the local operations and wants to get them right.

Align the Leadership of the Subsidiary with the Needs of the Board

One of the key concerns in governance pertains to the “principal-agency theory.” This is the theory that states human beings (agents) will do what they can to better themselves. Just as Nick Leeson started unauthorized trading, in his mind he justified his actions by initially thinking he was seeking to recover a loss suffered by the organization, and then later, to create wealth for his company and his colleagues. He had convinced himself that what he was doing was for the better good. While Barings (the principal) enjoyed his perceived successes, they would not have approved his activities if they had known he was making unauthorized trades. This natural conflict exists at many levels in an organization and starts with the board and their selected CEO.

How does the board ensure the CEO and management stay on track? They do it through a variety of hard and soft controls. The hard controls include board meetings, reports, audits, risk reviews, verifications, and other processes. The soft controls include company culture and, among other techniques, annual objectives and financial incentives. These incentives must be “fair” enough to reward the CEO and employees to avoid taking actions that might result in losing this compensation. The same control holds true for subsidiaries.

The incentives to stay on the right side of the governance lines must be in place for all members of the subsidiary's leadership team. I intentionally use the term “leadership team” rather than the management team as it connotes a behavior and not just an authority. Subsidiaries are often smaller organizations than the parent and lack a critical mass of other employees to share cultural values. The leadership team often forms the nucleus of role models in the subsidiary and must set the tone for all employees; and that tone must be consistent with the culture and objectives of the parent organization. This shared culture in the subsidiary is another soft control mechanism that states “the kind of company we aspire to be.” And that culture should be consistent with the subsidiary board's governance needs. If this subject in human dynamics and soft controls is of interest to readers, I recommend looking into the research and writings of Dan Ariely, professor of Behavioral Economics at Kent State University.

Identify the Operating Needs of the Parent: The “Non-negotiables”

Every corporation is unique and has policies and principles it holds dear. It also has unique systems, processes, and practices applicable to every unit in their network and all employees. Codes of conduct are often cited as being global in nature as well as mission, vision and values, and branding guidelines. As an example, a non-negotiable product for the international franchises of McDonald's hamburger chains might be the iconic Big Mac or the Quarter Pounder. As well as their highly recognizable golden arches logo, we would expect to see these global non-negotiables at every franchise. However, during a visit to Hawaii, I was surprised to see a McDonald's outlet offering a ramen soup called Saimin to their local patrons. The Hawaiian-style ramen noodle is a staple on the islands. They also serve Portuguese sausage and Spam with rice on their breakfast menu. These deviations from the North American menu are local favorites. They increase sales and do not conflict with the non-negotiables that are also on offer. The Big Mac that I enjoyed was exactly as it is served in my local outlet. These are examples of global needs, or “non-negotiables.” Other non-negotiables might include monthly or quarterly financial reporting, all employees signing the code of conduct, annual internal audits, and use of specific business systems or IT security systems.

Other areas where the parent might have strategic expectations in the way the subsidiary is formed or operates might include:

- Governance Structure: What kind of board and what directors need to be in place

- Leadership: Selection procedures for the managing director or CEO

- Financial Needs: A description of the CFO role, the finance team, finance systems, and reporting frequencies and processes

- Process Reviews: External auditor, internal auditor, risk management, compliance, human resources policies and reviews, and so on

- Global Cultural Needs: Vision and values, code of conduct, service expectations

- Systems: Software, hardware, HR systems (job grades, bonus structure, etc.)

- Branding: Logos, products, marketing, advertisements

Clarify and Align the Needs of the Subsidiary with the Parent Organization

Business decision makers sometimes overlook the need to align the needs of the subsidiary into the parent. These are often cultural, human resources–related, or product ideas like the Saimin soup on offer at McDonald's franchises in Hawaii. Another example might be a manager's benefit package that might include a car, a benefit not offered to a North American or European manager. This could exist for several reasons, including the notion that in some developing countries someone directing local employees within that country carries a sense of respect and authority in that culture. That authority is physically demonstrated in driving to work, a benefit not normally available to domestic employees in developing countries.

Another example might be the number of vacation days to which a starting employee is entitled. In North America, a new employee may be entitled to two weeks of vacation, in some cases only after completion of one full year of service. But under French law, an employee is entitled to accrue 2.5 days of vacation for every month worked. After a year that would be 30 days, not the 10 we see elsewhere. There will be many other local issues that the board will need to identify, wrestle with, and manage through.

So, how do you decide what to insist be consistent with the parent's domestic practices and when to allow the subsidiary room to accommodate local practices, tastes, and regulatory expectations?

Professor Martin Hilb of St. Gallen University, Switzerland, advises decision makers to follow four simple principles to achieve good governance and outstanding business results:

- Keep It Situational. This first principle advises that companies adapt their corporate practices so they can accommodate the local context within which they will operate. Like the manager's car or the Saimin soup in Hawaii, do these requests conflict with global strategy, values, or any other non-negotiable? If they do not, by inference they are negotiable and should be given consideration to better align the parent's usual processes with the practices familiar to local subsidiary employees and board. This principle requires that both parent and subsidiary boards understand and address the external context and cultural aspects of the international business operation and align it to the internal context of the parent corporation.

- Keep It Strategic. This second principle advises companies to have an effective strategy for the subsidiary that is aligned with the parent's own strategic plan. Once developed, keeping these strategies at the center of the subsidiary's focus is a non-negotiable, until they need to be updated. Keep these strategic intents at the center of decision-making and avoid slipping into areas that are not “on strategy.” This principle aligns the subsidiary with the company's strategies, activities, processes, and direction. This principle is further complemented by the fourth principle: Keep It Controlled.

- Keep It Integrated. This third principle advises companies to ensure that the subsidiary's board of directors have been carefully selected to form an integrated team. While this is also true at the parent level, aligning the subsidiary board and mandate with Kiel's strategies for entering and competing internationally (Figure 44.1) will provide insight to the skills and mandate of the subsidiary board. All boards need to be evaluated as a functioning body annually and individual directors need to be personally evaluated for their contribution and behavior and formally or informally provided feedback.

- Keep It Controlled. Hilb's final principle concerns one of the most critical factors for ensuring good corporate governance. “Keep It Controlled” advises companies to take a holistic view of their governance processes and include not only shareholders but also employees, customers, the public, and other stakeholders who would have an interest. Focusing on this broader stakeholder group allows the board and its management to have an expanded view on the control elements within their business. This broadened perspective must be front-of-mind when hard controls like audit, risk management, and operational control processes and procedures are created.

FIGURE 44.1 Degree of Freedom Model (Kiel)

These principles need to be applied to both the parent organization and the board as well as the subsidiary organization and its board. Although they may be aligned, both the parent and the subsidiary operate in different environments. Keeping It Situational for the subsidiary takes into consideration local factors. Keeping It Integrated brings both organizations together into operating and strategic alignment. When both the Local needs are satisfied as well as meeting the Global (parent's) needs, Hilb refers to that organization as being “Globally Responsive and Locally Effective, or GLOCAL.” (We will return to this term later.) To visualize how that balance between the parent's needs and the subsidiary's needs works in harmony, I have borrowed from Hilb and developed the following framework for subsidiary governance below (see Figure 44.2).

Readers interested in delving further into Hilb's principles and discovering other board and management tools to create effective strategic direction and control for their organizations are directed to Professor Hilb's insightful book: New Corporate Governance.

Understanding these concepts is a good first step, but how do we actually make it all work?

As discussed earlier, subsidiaries will have different purposes. Keeping It Situational means that different subsidiaries will require different degrees of freedom from the parent and that will affect subsidiary board makeup, product differentiation, brand management, needs for audits, reviews, and oversight, and likely even different HR policies. However, life does not remain constant—things change. How do we ensure that the needs of the parent organization for good governance and business success are met on an ongoing basis? How do we ensure that the needs of the subsidiary for unique cultural, regulatory, and product needs are met going forward? How do we ensure these important objectives continue to meet the parent's needs in business and governance as the subsidiary continues to evolve over time?

FIGURE 44.2 Framework for Subsidiary Governance of International Companies (Sears)

Source: My design, based on Hilb.

So far, we have:

- Developed and tested a detailed business plan that we now believe will work in the international jurisdiction to achieve the organization's business objectives.

- Researched the target geography for differences and similarities to the home market. We have engaged local advisors (potential future board directors) to help identify the differences in regulatory regimes and products, sales, manufacturing, and resources, including local staff, and have developed strategies around each.

- Identified the non-negotiables (needs) of the parent in operating this subsidiary and determined any local needs of the subsidiary that might present acceptable variations from the parent or the home market in staffing, human resource policies, language, and culture, as well as the Degree of Freedom this subsidiary will operate in over the long run.

- Determined what roles local and home office staff (expats) will play.

We can now recommend to the parent board the purpose and scope of the subsidiary and how operations and governance structures will work initially. But how do we ensure that continuity of business success and governance success continues as the subsidiary evolves in the future?

Making It Work—The Glue That Binds: “Trans-Cultural Conduits”

A great deal of care and attention is paid at the outset to new business ventures, including new international subsidiaries. This due diligence aims at ensuring the business case will work and the investment is right for the organization. Business and governance practices are set for a great launch. But how do we ensure the same degree of attention and information sharing continues in spite of the distance, time zones, and cultures, as changes occur? We need ongoing mechanisms to keep the parent-subsidiary relationship current, growing and changing in a positive way.

By comparison, the home unit operates in a familiar environment where news media is well monitored, and is supported by trusted advisors, like lawyers and accountants who are met with regularly both formally and informally. Information flows. Like employees meeting at the watercooler to discuss last night's game, they also learn the latest rumor circulating the organization. Information flows freely and people can react proactively.

With international units there are many moving parts. Some of these moving parts may not be well understood by leaders in the parent organization. Organizations are living entities. Things change. Local regulations will change, competition will change, products will change, new entrants and new technologies will come along, and although the parent cannot devote the same degree of time and attention as it did during the development stage of the international subsidiary, it is equally important that this ongoing monitoring be conducted for the long-term health of the subsidiary. However, to accomplish this going forward requires well-structured formal and informal communications conduits that involve others in the organization.

Geert Hofstede of Maastricht University provides insights on how to manage successfully across cultures by introducing two new terms: bi-culturality and link-pins.

Bi-culturality refers to senior people in both the parent organization and the subsidiary. Initially these may be the principals who led the investigation and the business case for the board's approval to open the subsidiary. From their experience and in doing their research these individuals from the parent organization have come to understand the operating nuances of the parent, including the non-negotiables, but also the operating variants of the subsidiary's environment. They have in a sense become bi-cultural and can talk both to the subsidiary to explain the parent's needs and operating expectations as well as to the parent to explain the subsidiary's needs. Over time this ability to translate between home and international will be extended to the subsidiary's leadership team, the parent's internal auditors, the finance and marketing teams in both locations, as well as other senior people who operate in one environment but have responsibility to understand the nuances of the other.

Link-pins are similar to bi-cultural managers but operate more on a day-to-day basis in both the parent and the subsidiary. This may include sales leaders who have dual reporting lines in the parent and the subsidiary, and other functions, including risk management and the teams in finance, systems, client services, and management. In time these link-pins operate seamlessly even across distances like employees at the watercooler with daily contact, who interact both formally as well as informally in understanding each other and in sharing information.

As the subsidiary continues to evolve, bi-cultural managers and link-pins in both locations will stay in touch formally and informally on matters of importance, both operationally and strategically. These people, or conduits, are the ties that bind.

When we reflect on Hilb's earlier reference to a parent and subsidiary having both Global Responsiveness and Local Effectiveness or being GLOCAL, it is equally important that these other key “needs” also stay current. They do so through a variety of people, but Hilb also includes “mechanisms” such as policies, procedures, systems, vison and values, strategic plans, governance processes, and culture. They may be monitored by bi-cultural managers and link-pins but it is of fundamental importance that these mechanisms are in place and also stay current as the subsidiary and the parent both continue to evolve.

Hofstede's bi-culturality and link-pins and Hilb's mechanisms for GLOCAL balance all work as conduits between the parent and subsidiary to ensure two-way communication both formally and informally between the parent and subsidiary. Conduits of people and mechanisms that allow the free flow of information exist in all organizations. But these are unique as they cross cultures and distances. They are fundamental to the ongoing success of the subsidiary. They work together in the framework I call “Trans-Cultural Conduits” (Figure 44.3).

FIGURE 44.3 Trans-Cultural Conduits (Sears)

Source: My design, based on Hilb & Hofstede.

Conclusion

Successful international operations can bring great benefits and prestige to a successful domestic business. However, as we have seen, international business success without governance success can be seriously detrimental to a parent organization and its board. Equally, international governance success without business success is also a failure. We need both and we need balance.

I hope this chapter has sparked new insights for you and your organization, and has provided a framework to be successful with your international plans and network. Best of success!

About the Author

Thomas C. Sears Sr. received his MBA (Dean's List) from the Rotman School of Management in Toronto and his PhD (Governance of International Subsidiaries) from St. Gallen University, Switzerland.

For over half of his 30-year career, he headed international subsidiaries for Canada's largest bank, with clients and correspondents across 50 countries. International business brings new complexities to leadership.

During the mid-1990s, international subsidiaries were making alarming headlines and depleting shareholder capital and costing employee jobs. In writing the working paper “Achieving International Business Success and Good Governance” (see http://www.tcsears.com/#publications), he tells the true story of one client losing its shareholder capital and all employee jobs. ENRON then made headlines losing its capital, 20,000 employee jobs, and 60,000 Arthur Andersen jobs.

Realizing his shareholders and employees expected him to avoid these disasters, he studied international subsidiary governance under leading experts.

Today he consults with boards having taught governance and other international business subjects to MBAs and executives at the Rotman School of Management.

References

- Hilb, Martin. 2016. New Corporate Governance (5th ed.). New York: Springer.

- Kiel, Geoffrey C., Nicholson, Gavin J., and Hendry, Kevin. 2006. “Corporate Governance Options for the Local Subsidiaries of Multinational Enterprises,” Corporate Governance: An International Review 14(6) (2006): pp 568–576.