16

Responsible Boards for a Sustainable Future:

Dr. Yilmaz Argüden

Founding Chairman of ARGE and Chairman of Rothschild

“Trust is the essence of good governance and the foundation of sustainable development.”

Introduction1

As external pressures, including resource scarcity, globalization, and access to information continue to increase, how corporations respond to sustainability challenges will determine their long-term viability and competitiveness. According to the latest McKinsey Global Survey2 on the topic, executives at all levels see an important business role for sustainability. The same survey results also show that aligning sustainability with core business strategy and stakeholders (like consumers, employees, investors) is the top reason for implementing sustainable business practices. Yet, there is significant room for improvement in the effectiveness of the execution and accountability of their sustainability programs.

As the world continues to get smaller, the mutual interdependence of the corporations and their stakeholders grows larger. To achieve success, institutions increasingly rely upon the utilization of not only their own resources, but also the resources of others. To be able to gain access to the resources of others, institutions need to create trustworthy relationships. Therefore, the key to success and development is gaining the trust of present and potential stakeholders. These stakeholders include not only shareholders, employees, labor organizations, and customers, but also those who provide credit to the company, those in its supply chain, and the governments in whose countries the business operates, in short, individuals and organizations in all parts of society.

For example, to be able to grow fast and compete globally, firms need to gain access to global credit or equity capital markets. Similarly, as the role of corporations in the development of the world's economy increases and the scope of their influence widens, so does the breadth of their responsibilities. The license to operate increasingly requires fulfilment of the firms' responsibilities to the community. The trustworthiness of corporate architectures, processes, and behaviors become an indispensable characteristic of the corporation not only for their shareholders, but also for their stakeholders.

Today, successful and sustainable organizations need: to demonstrate not only a willingness to involve the stakeholders in decision-making; to embrace a culture of transparency and accountability; to be fair and consistent in relations with stakeholders; but also, to have an organizational infrastructure that ensures “corporate trust.” Hence, good governance is the key to creating sustainable companies.

Many corporations' interest in sustainability issues started out as nice to have as part of their social responsibility programs and to build their corporate reputation. However, those who have taken it seriously as a board and CEO responsibility soon understood that paying attention to sustainability issues was in fact a great risk management technique, particularly since avoidance is much more economical than repairing corporate reputation after a significant failure (e.g., BP-Gulf of Mexico and Volkswagen-Diesel cases). Now, some forward-looking business leaders began to view the challenge of sustainability as an opportunity for value creation. They came to realize that if sustainability issues are becoming relevant for large numbers of people throughout the globe, addressing them properly would be a good business case for satisfying a global need. (See Table 16.1.)

Companies that have embraced these challenges and transformed them into an opportunity for innovation and long-term value creation gain several advantages:

- Innovation in products and ways of doing business

- Lower cost of capital and easier access to capital markets

- Lower cost of operation through less dependency on limited resources

Table 16.1 Evolution of the Sustainability Frontier

Corporate Social Responsibility Risk Management Tool Value-Creation Opportunity

Role of Sustainability - Sustainability efforts are de-coupled from strategy and financial metrics and used as a marketing tool

- Sustainability efforts are focused on compliance and opportunity for managing reputational and operational risk in volatile markets

- Sustainability is a core driver of strategy and innovation in products, ways of doing business, and managing stakeholders

Role of the Board of the Directors - Increasing marketing and brand equity

- Managing reputational risk due to globalization

- Reducing costs across the value chain as well as long-term resource dependence

- Ensuring regulatory compliance

- Resilience in volatility

- Competitive advantage and long-term viability

- Impact on solving problems

- Long-term resilience against volatility in commodity prices and resource constraints

- Increased loyalty from customers and employees

- Flexibility to experiment with new approaches

There are a number of reasons why progress has been slow for companies in viewing sustainability as a strategic imperative:

- Capital markets and investor expectations evaluate company performance through short-term financial metrics rather than long-term value creation.

- The complexity and diversity of stakeholder expectations and industry dynamics make it difficult to craft a one-size-fits-all approach to sustainability management, requiring each company to craft their approach to sustainability.

- As the costs of externalities are not internalized, companies do not incur the costs of not integrating sustainability into their performance metrics.

- There are limited data and tools for measuring returns through nonfinancial metrics (including social, environmental, and governance).

- The global nature of problems requires nontraditional partnership across corporate, nongovernmental, and public spheres as well as among competitors within the same industry to share the costs of initial investments and increase effectiveness of execution.

- Change requires successful execution within the company, including adoption of vision throughout the organization, its value chain, and product-cycle, which is increasingly difficult in today's multi-stakeholder world.

- The global nature of challenges and the lack of sovereign bodies make it difficult to impose penalties on responsible parties, slowing down progress.

Gaining competitive advantage and resilience in times of varied stakeholder expectations, increasing global challenges, and volatile markets require redefining the role of the corporation in today's society. Companies that have undertaken this challenge are transforming it into an opportunity by:

- Making sustainability a key leadership priority and part of core strategy

- Adopting long-term view for value creation and innovation

- Forming partnerships to move beyond the capabilities of individual companies to solve complex global challenges

- Focusing on capturing value across the value chain and product lifecycle to reach their sustainability targets

- Engaging stakeholders and increasing transparency on company performance

- Assessing risks and performance against nonfinancial targets in addition to financial targets before compliance requirements increase

- Ensuring sustainability initiatives are adopted throughout the organization

Role of the Board of Directors

The essence of good corporate governance is ensuring trustworthy relations between the corporation and its stakeholders. A board of directors sets the tone at the top and is responsible for ensuring the right climate and culture exists within the organization. Corporate boards of directors do not participate in day-to-day decision-making; instead, they provide guidance, set overall policy based on the corporate mission and vision, and exercise an oversight function, reviewing the actions of corporate officers and executives in order to ensure that the company creates value on a sustainable basis while protecting the interests of all stakeholders.

Sustainability is a long-term issue for companies. Boards are responsible for long-term decisions and guidance and strategy setting for organizations. Therefore, sustainability is a key board responsibility. Decisions like redesigning value chain, introducing new technologies, and investing in green innovations are some of the critical issues where boards need to take responsibility. Boards' time perspectives should be longer than those of the management teams. Hence, boards need to make sure that the top management does not fail to address key sustainability issues whose effects will be realized in the long term, exceeding managements teams' term.

The key to good corporate governance is ensuring that the principles of Consistency, Responsibility, Accountability, Fairness, Transparency, and Effectiveness are Deployed (CRAFTED)3 throughout the organization. Applying CRAFTED principles is a sine qua non of sustainable success.

Earning the trust of the stakeholders is the key to mobilize their resources toward a common vision. Transparency in relationships is the key to earning that trust. Success requires effective utilization of resources entrusted to a corporation. Being fair and accountable to all the stakeholders whose resources are entrusted to the corporation is the key to sustainability of access to those resources. The communication and behavior of each institution influences not only how its own resources are utilized, but also those of its stakeholders. Therefore, consistency of the policies of a corporation is key to ensure that right expectations are formed throughout the value chain, thereby making the whole value chain stronger. Value creation requires measured risk taking. Risk is the kin of profit. Therefore, taking initiative and responsibility, which naturally involves risk taking, is a key element of value creation. Sustainability of success requires continuous improvement and innovation. This in turn requires learning and the participation and involvement of all in the organization. Hence, creation of a climate which emphasizes good governance principles and deployment of a good corporate governance culture is the key for sustainability.

The board members, as stewards of public trust, must always act for the good of the organization and need to exercise reasonable care in all decision-making, without placing the organization under unnecessary risk. Furthermore, as key decision makers responsible for the success of the corporation, they need to ensure that the corporation gains and retains the trust of present and future stakeholders. Both this risk management role and value-creation responsibility call for fair treatment of the stakeholders.

The term fiduciary refers to a relationship in which one person has a stewardship responsibility of care for the assets or rights of another person. A fiduciary is an individual who has this responsibility. The term fiduciary is derived from the Latin term for faith or trust. The term stewardship implies an inherent willingness to serve others (a moral duty), and a willingness to subordinate one's interests to those of others by acceptance of the duty to serve.

As early as 1790 B.C. the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi established rules of law governing business conduct for the behavior of agents entrusted with property.4 Aristotle (384 B.C.–322 B.C.) influenced the development of fiduciary principles, recognizing that in economics and business, people must be bound by high obligations of loyalty, honesty, and fairness, and that when such obligations are not required or followed, society suffers.5

Corporate board members have a fiduciary responsibility to act in good faith and with a reasonable degree of care, and they must not put themselves in any conflicts of interest. The fiduciary responsibilities of board members fall into three categories: duty of loyalty, duty of care, and duty of full and fair disclosure.

The duty of loyalty imposes on the board an affirmative duty to protect the interests of the corporation, and also an obligation to refrain from conduct which would injure the corporation and its shareholders. Directors must avoid any conflict between duty and self-interest. Undivided allegiance to the corporation's best interest is required.

The duty of care requires directors to make a business decision based on all available and material information and to act in a deliberate and informed manner. First, the board members must act in good faith for the company's best interest. Second, they must believe that their decisions promote the best interest of the corporation in both the short and the long term based on a reasonable investigation of the available options.

The duty of full disclosure is to provide reasonably complete disclosure especially when shareholders are asked to vote and when the company completes a conflict-of-interest transaction. However, extending the duty of full and fair disclosure further to include environmental, societal, and governance matters is critical for gaining and retaining the trust of present and future stakeholders.

According to the Conference Board,6 recently the notion of fiduciary duty is expanding to include sustainability issues. Increasingly the pursuit of sustainable business initiatives is viewed as consistent with corporate governance standards. In particular, judicial action7 and recent stakeholder constituency statutes8 and statutory exculpatory provisions under corporate law9 have laid the groundwork for boards to consider non-shareholder interests and concerns in making investment decisions.10 Similarly, in 2009 the Committee for Economic Development issued recommendations on the potential contributions that boards of directors can offer to improve overall business performance while responding to societal concerns.11

Therefore, the responsibilities of the board members are not limited to short-term interests of the shareholders, but also include long-term impacts on anyone affected by their decisions and future generations. As “trusted” agents, board members need to ensure that the stakeholders “trust” the corporation to ensure their long-term commitment to work with the corporation toward achieving its mission.

Emerging Standards of Sustainability

According to the Brundtland Commission (Our Common Future report) of the United Nations on March 20, 1987: “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” The United Nations Millennium Declaration identified principles and treaties on sustainable development, including economic development, social development, and environmental protection. The 2005 World Summit on Social Development confirmed the same dimensions for the sustainable development goals. These three pillars have served as a common ground for numerous sustainability standards and certification systems in recent years. Later, the United Nations Agenda 21 specified culture as the fourth domain of sustainable development.

One of the main outcomes of the Rio+20 Conference in 2012 was the agreement by member states to launch a process to develop a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which have been built upon the Millennium Development Goals and converge with the post-2015 development agenda. The outcome document of Rio+20, The Future We Want, resolved to establish an inclusive and transparent intergovernmental process on SDGs that is open to all stakeholders with a view to developing global sustainable development goals to be agreed by the UN General Assembly. In September 2015, 17 aspirational, action-oriented SDGs have been agreed upon by the UN General Assembly. The SDGs cover areas such as: poverty reduction, universal access to health, education, energy, and water; reducing inequalities; climate change and environmental protection; and promoting peace and good governance throughout the globe. (See Table 16.2.)

UNFCCC Climate Conference COP21 was held in Paris in December 2015. An agreement to combat climate change and unleash actions and investment toward a low-carbon, resilient, and sustainable future was agreed by 195 nations in Paris. The Paris Agreement for the first time brings all nations into a common cause based on their historic, current, and future responsibilities. The universal agreement's main aim is to keep a global temperature rise this century well below 2° Celsius and to drive efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels.12 The Paris Agreement and the outcomes of the UN climate conference (COP21) cover all the crucial areas identified as essential for a landmark conclusion:

Table 16.2 SDGs

| Goal | Description |

| Goal 1 No Poverty | End poverty in all its forms everywhere |

| Goal 2 Zero Hunger | End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture |

| Goal 3 Good Health | Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages |

| Goal 4 Quality Education | Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all |

| Goal 5 Gender Equality | Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls |

| Goal 6 Clean Water | Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all |

| Goal 7 Affordable Energy | Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all |

| Goal 8 Decent Work | Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all |

| Goal 9 Industry, Innovation, Infrastructure | Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation |

| Goal 10 Reduced Inequality | Reduce inequality within and among countries |

| Goal 11 Sustainable Cities | Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable |

| Goal 12 Responsible Consumption & Production | Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns |

| Goal 13 Climate Action | Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts |

| Goal 14 Life below Water | Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development |

| Goal 15 Life on Land | Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss |

| Goal 16 Good Governance | Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels |

| Goal 17 Partnerships | Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development |

- Mitigation—reducing emissions fast enough to achieve the temperature goal

- A transparency system and global stock-take—accounting for climate action

- Adaptation—strengthening ability of countries to deal with climate impacts

- Loss and damage—strengthening ability to recover from climate impacts

- Support—including finance, for nations to build clean, resilient futures

All 195 countries made a commitment to submit climate action plans to reach the goals. Corporations would be part of these plans and would have responsibility in reaching the national and international targets. Addressing challenges in a global scale requires governments to devise innovative ways of partnering with other governments, corporations, and civil society, developing accountability structures, and changing national education systems. Solving problems such as decreasing carbon emissions or water scarcity requires multi-stakeholder problem-solving, execution, and accountability.

Although the United States has decided to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement in June 2017, a number of U.S. companies, cities, and states declared to follow the Paris Climate Agreement, which is a strong sign for acceptance of sustainable and responsible business conduct both by public and private actors.

In short, a sustainable global economy is one that combines long-term profitability with ethical behavior, social justice, and environmental care. Sustainability is improving the quality of human life while protecting the potential of future generations to do the same. Good governance is also a responsibility toward a sense of universal commitment to sustainable development. Table 16.3 lists widely accepted voluntary standards and guidelines that influence priorities in sustainability reporting and sustainable investing.

UN Global Compact

Initiated by Kofi Annan's13 speech to Davos participants in 1999, the UN Global Compact is a strategic policy initiative for businesses whose CEOs make a commitment to aligning their operations and strategies with ten universally accepted principles in the areas of human rights, labor, environment, and anti-corruption.

Table 16.3 Global Sustainability Initiatives

| Initiative | Description |

| UN Global Compact (UNGC) | The UN Global Compact is a strategic policy initiative for businesses that are committed to aligning their operations and strategies with ten universally accepted principles in the areas of human rights, labor, environment and anti-corruption. |

| OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (GME) | The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises are recommendations addressed by governments to multinational enterprises operating in and from adhering countries. They provide nonbinding principles and standards for responsible business conduct in a global context consistent with applicable laws and internationally recognized standards. |

| UN Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) | PRI aims to help investors integrate the consideration of environmental, social, and governance issues into investment decision-making and ownership practices, and thereby improve long-term returns to beneficiaries. |

| Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) | GRI promotes the use of sustainability reporting as a way for organizations to become more sustainable and contribute to sustainable development. |

| International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) | IR is a process founded on integrated thinking that results in a periodic integrated report by an organization about value creation over time and related communications regarding aspects of value creation. |

| Guidance Standard on Social Responsibility (ISO 26000) | ISO 26000 provides guidance on how businesses and organizations can operate in a socially responsible way through organizational governance, human rights, labor practices, the environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues, and community involvement. |

| Equator Principles | The Equator Principles (EPs) is a risk management framework, adopted by financial institutions, for determining, assessing and managing environmental and social risk in projects and is primarily intended to provide a minimum standard for due diligence to support responsible risk decision-making. |

Kofi Annan's call to action was operationalized brilliantly14 with a very simple but very effective requirement for the signatories: that they would annually report (Communication on Progress, COP) to the UN Secretary General what they are doing for each of the ten universally accepted principles, confirmed by their CEOs signature, and that these reports would be publicly available. There are no specific targets (each organization picks their own targets), there is no third-party verification (although this is recommended, it is not a requirement), and the initiative is totally voluntary. There is only one penalty for those who fail to report: to be delisted from the UN Global Compact signatories list.

However, this simple requirement of annual Communication on Progress by organizations that voluntarily signed on has served extremely well. First, organizations from different geographies and different scales have picked achievable targets that were appropriate for themselves. This in turn improved their motivation to do even better each year. The requirement of CEOs signature provided much-needed focus on each organization's voluntary activities on these principles and improved both resource utilization and deployment throughout the organization and geographies. Competitive instincts of corporate leaders pushed them to do better each year rather than seeing the target they have picked for themselves as regulatory hurdles to be met. So, a virtuous cycle for continuous improvement was set in motion. Also, the fact that the reports are publicly available has provided both a self-discipline and potential for review by other stakeholders, as well as a benchmarking and a learning opportunity from peers.

Under the able leadership of its founding executive director, Georg Kell, in 15 years the UN Global Compact has become the largest voluntary corporate responsibility initiative and sustainability platform in the world. By 2018, there are more than 13,200 signatories, over 9,800 of which are businesses, from over 161 countries. More than 100 countries have established Local Networks of Global Compact signatories in their respective countries,15 increasing mutually beneficial collaboration and learning opportunities. On a global scale these national networks meet annually to learn from each other and provide guidance to the overall development of the initiative.

UN Global Compact was recognized as a role model initiative in the B20 recommendations to the G20 in Antalya on November 2015.16

OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

The Guidelines provide voluntary principles and standards for responsible business conduct in areas such as employment and industrial relations, human rights, environment, information disclosure, combating bribery, consumer interests, science and technology, competition, and taxation.

The Guidelines are a leading tool to promote responsible business conduct in the changing landscape of the global economy. Observance of the Guidelines by enterprises is voluntary and legally not enforceable. Yet, a significant number of companies on the FTSE4 Good and Dow Jones Sustainability Index refer to the OECD MNE Guidelines in their corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports.

The fact that OECD countries have endorsed the Guidelines is a differentiating factor from other voluntary initiatives. The Guidelines are applicable to large and to SME multinational enterprises; the criterion is not the size but the multinational character of the company. Although the content of the Guidelines does not apply to non-MNEs, it can well be relevant for non-MNEs, especially as a source of inspiration.

Principles for Responsible Investment

Developed with the contributions of a multi-stakeholder group including the global investment industry, intergovernmental organizations, civil society, and academia, the Principles for Responsible Investment Initiative (PRI) is an investor-led coalition in partnership with the United Nations Environmental Program Finance Initiative and the United Nations Global Compact.

More than 2,140 asset owners and investment managers who are decision makers for $90 trillion of assets under management are PRI signatories. They explicitly accept that their fiduciary role calls them to incorporate environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) issues into their investment decisions. They are a powerful force that is giving an impetus to responsible business.

The Principles are voluntary and aspirational. The PRI Initiative has quickly become the leading global network for investors to publicly demonstrate their commitment to responsible investment, to collaborate and learn with their peers about the financial and investment implications of ESG issues, and to incorporate these factors into their investment decision-making and ownership practices.

Not only investors and managers of huge assets are beginning to focus on responsible investment, thereby providing financial incentives for responsibility in boardrooms, but also credit markets are developing with an increasing focus on transparency and reporting the environmental and climate impact of supported projects.

Global Reporting Initiative

GRI's Sustainability Reporting Framework is a reporting system that enables all companies and organizations to measure, understand, and communicate four key areas of their performance and impacts: economic, environmental, social, and governance. GRI's mission is to make sustainability reporting standard practice. GRI provides one of the world's most prevalent standards for sustainability reporting. GRI Guidelines seek to enhance comparability between different corporations' sustainability reports by providing a holistic framework and encouraging the use of common indicators.

GRI has issued its first reporting framework in 2000 and over the years the GRI framework has become the benchmark for best practice in sustainability reporting. Over 46,000 companies now use the GRI framework as the basis of their reporting.

The GRI framework has gone through a series of evolutions and its most recent version, G4, is a major overhaul. In particular, G4 is focusing on supply chain materiality and allowing companies to report only on what matters most to them. Many companies' greatest sustainability impacts are in the supply chain. By encouraging the companies to explore and report more detail about suppliers, G4 aims to improve their overall sustainability performance.

Also, with the aim of putting sustainability higher on the board's agenda and ensuring a better link between sustainability and remuneration, G4 is increasing its disclosure requirements around governance and remuneration with new indicators.

GRI has strategic partnerships with the UN Global Compact, the OECD, ISO, and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

International Integrated Reporting Council

Launched in 2010 by HRH the Prince of Wales, the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) is a global coalition of regulators, investors, companies, standard setters, the accounting profession, and NGOs. Its mission is to create the globally accepted International Integrated Reporting Framework that would improve disclosure on the organizations' value-creation process by incorporating material information about the organizations' strategy, governance, performance, and prospects in a clear, concise, and comparable format.

An integrated report aims to provide insight about the all material resources and relationships used and affected by an organization. It seeks to explain how the organization interacts with the external environment and the financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural capitals to create value over the short, medium, and long term. It is seeking to forge a global consensus to establish a single, unified approach to financial and sustainability reporting. More than 80 international organizations have signed up to be part of the IIRC's network program. According to the Founding Chairman of the initiative, Mervyn King: “A key challenge for leadership is to make sustainability issues mainstream. Strategy, risk, performance, and sustainability have become inseparable; hence the phrase ‘integrated reporting.’”17

Under the Turkish Presidency of the G20, integrated reporting was among the B20 recommendations to the G20:

Implementation of inclusive and sustainable development will depend on the active engagement of the public private, and non-governmental sectors, including but not limited to the increasing number of actors signing the UN Global Compact and UN Principles for Responsible Investments (UNPRI). Good governance and responsible behavior by all actors should be established by creating a regulatory environment where transparency in the public and private sectors is the norm. Embracing reporting best practice and encouraging market-led initiatives, such as Integrated Reporting, focused on communicating value creation and sustainability performance across the economy would be the most effective way of improving transparency and building trust.18

International Organization for Standardization's Social Responsibility Standards

ISO 26000 provides guidance on how businesses and organizations can operate in a socially responsible way that contributes to the health and welfare of society. Developed through a multi-stakeholder process, ISO 26000 is a voluntary guidance standard and applicable to all organizations, not only limited to corporations.

The Standard covers seven key principles, advocated as the roots of socially responsible behavior: Accountability, Transparency, Ethical behavior, Respect for stakeholder interests, Respect for the rule of law, Respect for international norms of behavior, and Respect for human rights. The core subjects, which every user of ISO 26000 should consider are organizational governance, human rights, labor practices, environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues, and community involvement and development.

The Standard involves a seven-step approach to sustainability:

- Working with stakeholders to recognize their concerns

- Defining the scope of social responsibility for the organization

- Designing enterprise-wide procedures to integrate the sustainability program into the organization's mission, vision, strategies, and policies

- Overseeing the implementation of the procedures

- Communicating on social responsibility internally and through public disclosure

- Evaluating the sustainability program through performance metrics

- Making continuous improvements through the learnings achieved

Equator Principles

The Equator Principles (EPs) is a risk management framework, adopted by financial institutions, for determining, assessing and managing environmental and social risk in projects and is primarily intended to provide a minimum standard for due diligence to support responsible risk decision-making. The EPs apply globally, to all industry sectors and to four financial products:

- Project Finance Advisory Services

- Project Finance

- Project-Related Corporate Loans

- Bridge Loans

The relevant thresholds and criteria for application are described in detail in the Scope section of the EPs.19 EP signatories (80+ top financial institutions) do not provide finance to the projects that are not satisfying the requirements of EPs. EPs also helped the convergence of environmental and social standards in the financial sector.

Collaboration between these initiatives is increasing. For example, the former and now honorary chairman of GRI, Mervyn E. King, is also chairing the IIRC. UN Global Compact has signed a cooperation agreement with the GRI and is promoting utilization of GRI for its own Communication on Progress (COP) reports. In July 2014, the Boards of UN Global Compact, PRI, and PRIME (UN Principles of Responsible Management Education) met jointly in New York. More than 500 business schools are signatories of the UN PRIME. In doing so they have committed to addressing this need for change in leadership capabilities through education, research, and engagement. However, universities and governments have been slow to create opportunities and rewards for interdisciplinary research and broad public dissemination of research results. The mechanisms by which universities are funded, journals are ranked, and academics are assessed discourage academics from engaging with real problems and communicating their work to those who can act upon it.20

Responsible Boards

In order to move toward a more sustainable future, we need to have organizations who assume their sustainability responsibilities and act upon them. Corporations have the opportunity to be at the forefront of this change with their resources, efficiency, innovation capabilities, and access to talent. While the key implementation responsibility lies with the CEOs, the top decision-making bodies for the organizations, their boards of directors, have a critical role to play in providing guidance and oversight to the management for a better future for humanity.21

Regardless of the mechanism in order to fulfill their sustainability responsibilities properly, the boards need to ensure that:

- The corporation's sustainability goals are made part of the business strategy that the board oversees.

- Appropriate resource allocations, organizational infrastructure, and responsibility assignments are made.

- Internal control and monitoring systems properly incorporate sustainability issues and are effective.

- An adequate process has been established to engage the stakeholders to allow for inputs from stakeholders.

- There is a rigorous sustainability risk analysis process that focuses on current and future impacts throughout the value chain and lifecycle of the product portfolio.

- There is a verifiable process to measure the progress toward corporation's sustainability targets.

- An effective internal communications and educational platform is established to regularly inform and motivate all organizational ranks.

- The key sustainability performance indicators are incorporated into the corporation's information, hiring, and incentive systems.

- The corporation is transparent and accountable with its sustainability efforts and disclosure policy.

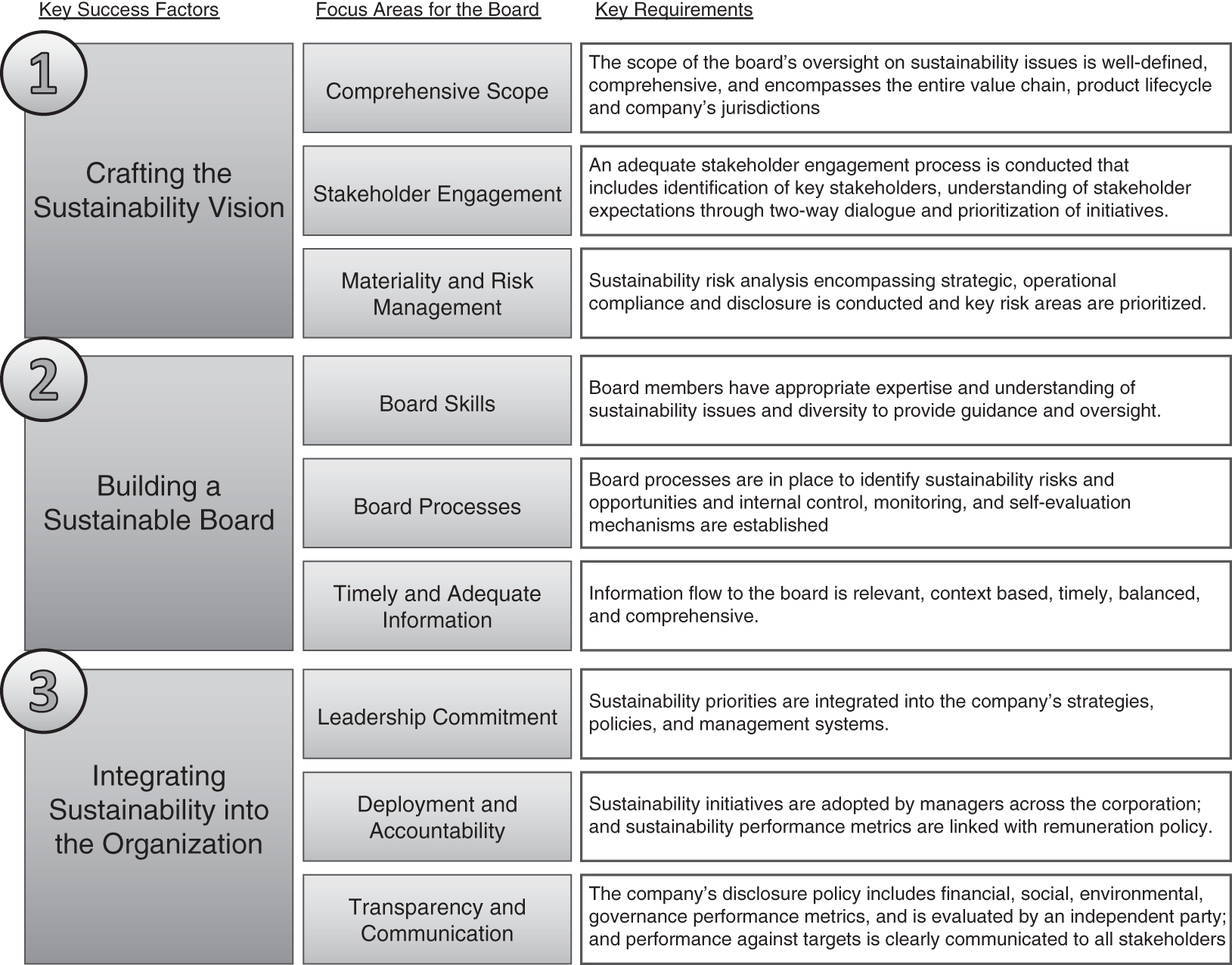

Responsible boards need to actively engage in embedding the SDGs and COP21 responsibilities to their corporations' business strategies to create sustainable value for all stakeholders, realize benefits for their shareholders, and be a leading institution for a sustainable world. (See Figure 16.1.)

FIGURE 16.1 The Board's Sustainability Responsibilities

1. Crafting the Sustainability Vision

Defining Sustainability Responsibilities with a Comprehensive Scope

The boards should clearly define their sustainability responsibilities through a Sustainability Charter.22 The Charter should clearly specify the scope of the board's23 oversight of sustainability issues; specifically reference the company's priority sustainability issues; make the linkages with the business strategies and priorities; and provide a framework for the integration with the company's risk management systems.

The scope of sustainability issues that need to be covered should include a comprehensive set of subjects such as safety, health, environmental, and community impact, human rights, labor rights, anti-corruption, and business ethics. Another key issue to consider is the standards of conduct and level of implementation in all the jurisdictions that the company operates in. OECD MNEs Guidelines particularly focus on this issue.

Supply chains are critical links that connect an organization's inputs to its outputs. Sustainability efforts of many companies are limited to measuring the sustainability of their own business operations and do not extend these efforts to their suppliers and customers. However, brand owners need to accept responsibility throughout their value chains. This may involve utilizing their purchasing power to encourage, audit, collaborate with, and provide benchmarking and learning opportunities with its suppliers on key sustainability issues. Apart from such engagement with the suppliers within the value chain, approaches such as supplier management, product design, manufacturing rationalization, and distribution optimization can be utilized to minimize negative externalities throughout the company's value chain. Furthermore, the sustainability impacts of the company's activities further downstream, including its final customers, can also be mitigated by product design and customer education. In short, the company should manage the impact of all its activities, including its supply chain as well as its full product portfolio24 throughout the lifecycle of its products.

Hence, the boards need to focus not only on the sustainability issues arising from company's own operations, but also on minimizing the impacts throughout its value chain and throughout the lifecycle of its full product portfolio.

Materiality and Risk Management

Despite the fact that market performance is currently measured through short-term financial returns, sustainability issues are becoming more relevant for investors, customers, and the communities. According to the Intangible Asset Market Value25 report only 20 percent of an S&P 500 company's market value can be explained by its physical and financial assets (down from 83% in 1975) and the remainder comprises intangible factors, such as intellectual capital,26 human capital, brand and reputation, and relationships with regulatory bodies, nongovernmental organizations, customers, suppliers, and other external stakeholders.

Therefore, sustainability issues that may have an impact on these intangible areas pose a significant risk for the value of a company. Boards need to seriously consider sustainability risks in four dimensions: strategic, operational, compliance, and disclosure. The sustainability risk analysis for the company would typically include seven questions:

- Which aspects of sustainability issues are relevant for the company?

- What are the procedures and tools utilized for the assessment?

- What are the short- and long-term economic, environmental, and social impacts?

- What are the major synergies, conflicts, and trade-offs?

- What measures can be put in place to mitigate harmful impacts?

- How does the management handle variability, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) around the key issues?

- What is the least-cost (economic, environmental, and social) mitigation option?

The responses to these questions should assess stocks and flows of economic, environmental, human, and social impacts; identify positive, negative or constant trends; determine degree to which effects can be reversed; determine degree to which negative impacts are shifted to future generations; and estimate long-term costs of failure to act at present.

The boards need to ensure that the material issues that would substantively affect the company's strategy, business model, capital, or performance are properly identified. In doing so the boards need to be actively involved in setting the materiality thresholds and ensure that the trends and current and future impacts have been considered. Boards also need to ensure that the management has prioritized the key sustainability issues and considered the resource requirements to deal with the prioritized issues in its mitigation plans.

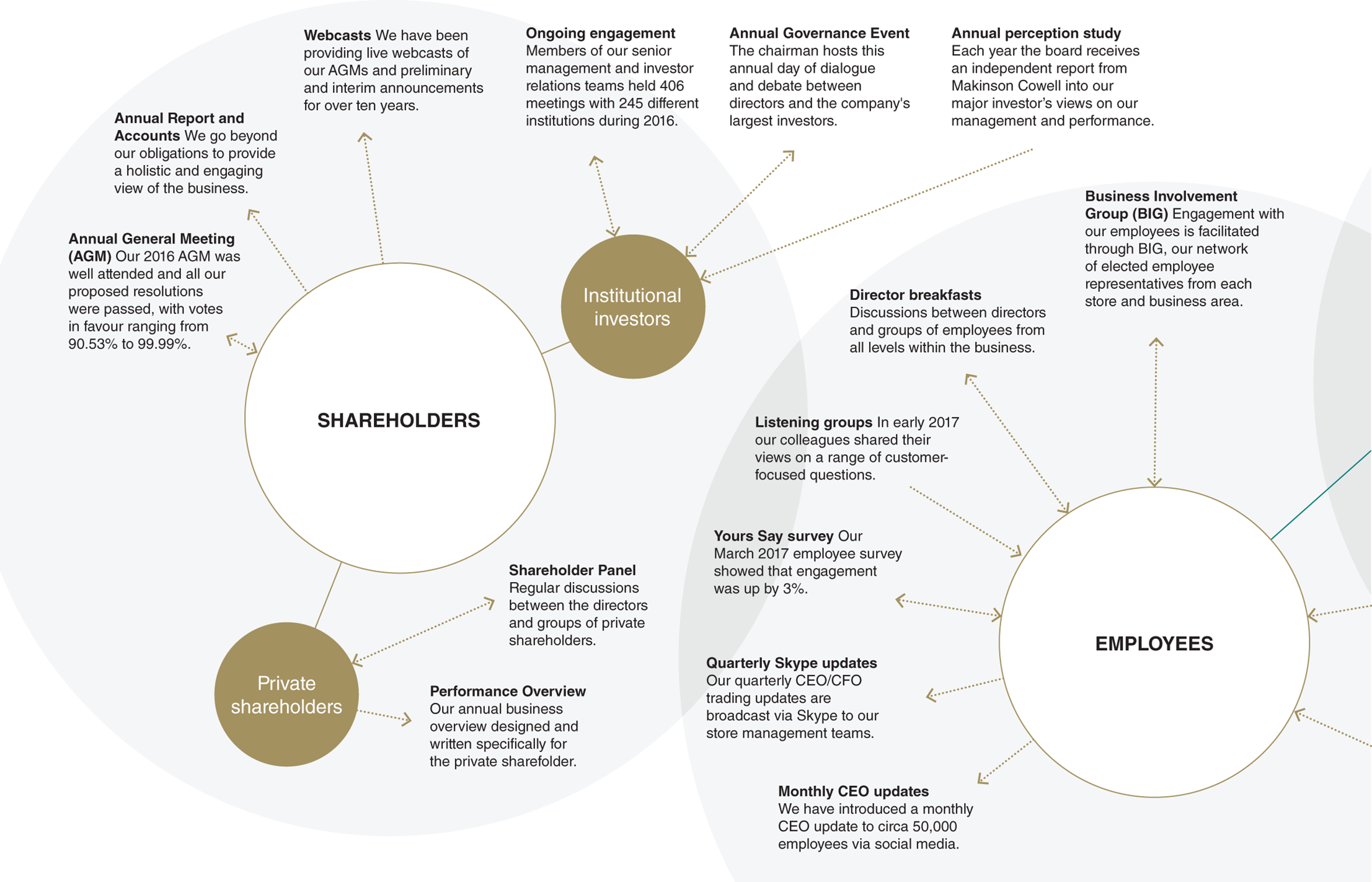

Stakeholder Engagement

Stakeholder engagement is a critical process that helps companies understand their key environmental and social impacts and identify sustainability risks and opportunities. First, the company needs to prepare a map of its key stakeholders for the issue at hand. Then comes the choice of the engagement model, communication, consultation, participation, and partnership, with each level requiring more resources. Tools of engagement may include interviews, workshops, focus groups, town-hall meetings, stakeholder perception surveys, stakeholder panels, and joint decision-making.27 The boards need to understand the key issues raised by the stakeholder engagement process and how the management plans to address them. See, for example, Figure 16.2.

FIGURE 16.2 Examples for Value-Adding Stakeholder Engagement Model

2. Building Sustainable Boards

Ensuring a Board with Appropriate Skills

Boards need to have members who understand the impact organizations have on the environment, their employees, and society in general. Corporate boards have to make difficult trade-offs when considering actions that are not positive contributors to all areas of sustainable effectiveness.28 Therefore, boards need to receive good information about the environmental performance and social impact of their corporation.

There are two key roles for the boards: providing guidance and providing oversight.

The guidance role of the board requires setting the strategic direction, controlling the executive recruitment, and motivating the right kind of management behavior by setting the executive remuneration policies, understanding the stakeholder concerns by an effective stakeholder engagement process, and providing leadership and a climate of continuous learning and development.

The oversight role in turn requires setting up an effective internal control mechanism, ensuring independence of audit and strict compliance, monitoring ethics and business conduct within the company and its value chain, and transparency in external reporting and disclosure.

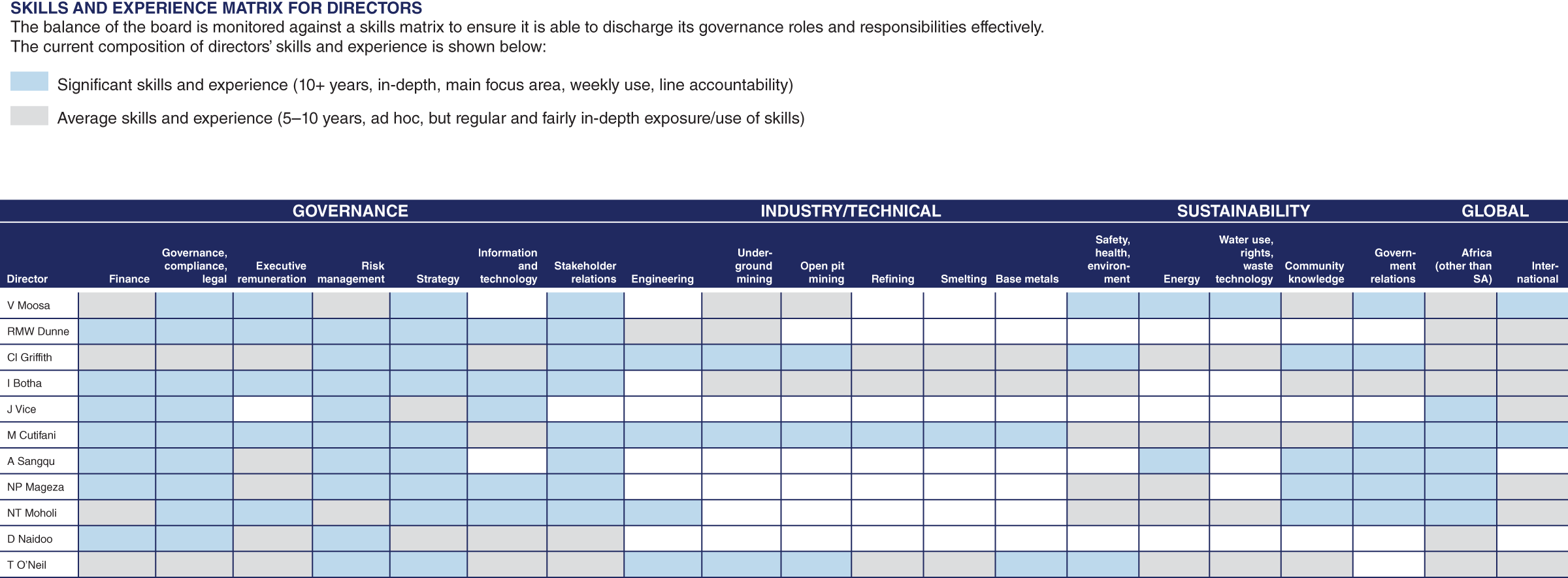

Therefore, boards need to have members who not only are experienced in providing guidance and oversight, but also have a sound understanding of the concerns and decision-making processes of the company's stakeholders, as well as familiarity with the sustainability issues and the evolving sustainability standards and benchmarks. These matters need to be considered both at the recruitment stage for board members and at the design and implementation of the orientation and board education programs.

Among 192 Global Sustainability Leaders (GSLs) listed in stock exchanges of China, Germany, India, South Africa, Türkiye, United Kingdom, and United States of America, only 29 companies published their skills matrix and 12 of them included sustainability as a valuable board skill. Further, analysis of the CVs of the GSLs' board members, in detail, indicated that 70 percent of them do not have a single board member with any sustainability reference in their CVs. However, there are very good examples, such as Anglo American Platinum, that not only included sustainability as a key board skill but also provide information about each board member's experience on various aspects of sustainability such as safety, health, and environment, energy, water-use rights, waste technology, and community knowledge. (See Figure 16.3.)

FIGURE 16.3 Example for Skills Matrix

In order to gain and retain the trust of stakeholders the most important issue is to have the right attitude. The yardstick should be the ethic of reciprocity that is prevalent in most religions and philosophers' writings and summarized as “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”29

Recent studies have shown a positive correlation between board diversity and both strategic innovation and corporate reputation.30 Board diversity, in all senses of the word, including but not limited to gender diversity, is important in ensuring the board is fit to drive change toward a sustainable business. Diversity of age, tenure, gender, ethnicity, cultural background, geographic, functional, and industry experience ensures that multiple perspectives are represented as the board engages in strategic discussions and makes long-term business decisions.31,32,33

In order to adequately evaluate the different dimensions, perspectives, and risks of the sustainability issues, industry experience diversity would be useful to better understand benchmarking opportunities. Tenure diversity would help avoid groupthink. Age diversity is recommended to better understand the sensitivities of different cohorts of customers and stakeholders. Ethnic, gender, and geographic experience diversity improves understanding of the sensitivities of different social segments and markets. Finally, stakeholder experience diversity helps better understand decision-making processes of different stakeholders. See Table 16.4 for key points.

Board Processes to Support Sustainability Responsibilities

Many boards establish a separate Sustainability Committee34 to review the sustainability risks and remedial plans to highlight the key issues for the full board to consider.

At a minimum the following steps should be taken by the Sustainability Committee:

- Identification and management of key social and environmental issues and ensuring the reliability of social and environmental performance management information

- Identification of and engagement with key stakeholders

- Monitoring the efficiency and effectiveness of sustainability management systems and controls

The boards need to understand the sustainability risks and impacts across the corporation's value chain and how this might impact the business model and competitive positioning of the corporation. They need to focus on sustainability-driven innovation and value-creation opportunities and provide guidance on the relationship of sustainability issues with the corporate strategy.

Table 16.4 Highlights for More Diverse Skills in the Board

| Sustainability: |

|

| Digitalization: |

|

| Risk Management: |

|

| Human Resources: |

|

| Innovation: |

|

The boards also need to provide sufficient oversight to the management's identification of risks and opportunities of sustainability issues, including those related to strategy, regulatory and legal liability, product development and pricing, disclosure, and reputation, as well as the management's action plans. In doing so, the boards' unfettered access to outside experts should be assured. In-camera sessions with these experts are recommended to receive independent advice.

The sustainability committees and/or the boards need to have access to stakeholder engagement processes in order to be able to form independent views on the highlights of stakeholder concerns. Yet, it is critical that the members should not put themselves in a position to commit the company for any course of action as that is a management responsibility; the board is a decision-making body as a team.

The boards also need to ensure that the internal control and monitoring systems provide sufficient attention to sustainability issues, compliance, and timeliness and adequacy of external reporting. Obviously, all these activities take time and therefore the boards need to allocate sufficient time and resources to deal with sustainability risks and management plans to address them. The time allocation should consider the breadth and immediacy of key sustainability issues that need to be addressed.

The board deliberations should also include evaluation of the adequacy of the D&O insurance package to sufficiently protect the directors against liabilities arising from sustainability issues. Boards should institute a learning and continuous improvement process for their own operations by incorporating the recommendations of the insurers into their sustainability plans and by conducting a regular self-evaluation exercise that evaluate the board's approach and effectiveness in providing guidance and oversight on sustainability issues. Many companies utilize independent third-party experts to help conduct a comprehensive and objective self-evaluation process.

Information Quality Determines the Decision Quality

Information flow to the board needs to be relevant, context based, timely, balanced, and comprehensive.

Balance refers not only to the amount of different dimensions of information, but also to its detail. Relevance and context are two key elements of board information. Putting information into context requires an ability to show the bigger picture as well as including comparative benchmarking data. Relevance of information in turn is related to the decision-making process. The board has to understand the issue, and the options, costs, risks, and impacts of each option for different stakeholders. Comprehensiveness refers to the different dimensions of sustainability, including social, environmental, and governance aspects. Environmental impacts may also include a broad range of issues, anywhere from carbon emissions to biodiversity, from energy efficiency to water and air pollution, and so forth.

For information to be useful, it needs to be presented within a context which should include comparisons with past performance and budget targets, lead indicators, current trends, emerging issues, emerging benchmarks, compliance with applicable laws and regulations, and the key upcoming regulations and standards.

Generally financial information is more readily available and presented in great detail, ignoring other key information requirements for quality decision-making such as information about the level of intellectual capital and reputation of the corporation, and supplier, customer, employee, and community satisfaction surveys. Yet, these types of information may have a greater relevance for the future value of the corporation and for the board members to fulfill their stewardship roles.

In order for the board to exercise its oversight responsibilities, it should receive findings and recommendations from any investigation or audit by internal audit department, external auditors, regulatory agencies, corporation's insurance companies, or third-party consultants concerning the corporation's sustainability matters on a timely basis.

Finally, the board should determine the key sustainability performance indicators (KPIs) they would like to follow on a regular basis and to incorporate into the executive remuneration policies. They should also receive regular information on these KPIs to be able to monitor progress toward sustainability goals.

All these decisions, which have been made through this decision-making process by using the provided information, have a financial impact on the company's balance sheet and will be a key determinant in calculating enterprise value of the business itself.

3.Integrating Sustainability into the Organization

Leadership and Culture

Good governance is a culture, a climate, and a set of behaviors that is exhibited throughout the organization, followed everywhere and every time, without written instruction or explicit mention. The tone at the top sets the corporate culture. Therefore, not only the conduct of the board members, but also their decisions and how they communicate these decisions are critical. All the members of the board should support, improve, and guide the corporate culture with their actions.

Corporate culture is the cornerstone of creating trust inside and outside the company.

Furthermore, the boards need to consider incorporating sustainability consciousness as a key criterion in choosing CEOs and filling the other top executive positions. The potential candidate needs to have strong conviction to convince others to follow and an appreciation that identifying sustainability risks requires stakeholder engagement. The boards also need to hold the CEO to account on the sustainability performance of the corporation by incorporating sustainability performance data to inform its deliberations on executive remuneration policies.35

Open-minded, early, and honest communication is a key enabler of a good governance culture. Transparency requires that analyses, decisions, and actions are documented, put into context, and considered for materiality. Information relevant for governance needs to focus on costs, risks, options, and impacts. Its context, timeliness, and comparison with relevant benchmarks are more important than its ultimate precision. Therefore, it is the management's responsibility to explain the bigger picture, issues, options, and recommendations in a way that is up-to-date and comprehensible, and in an executive format.

Creating an appropriate climate for learning is a critical leadership challenge. Actions speak louder than words. Therefore, leaders who wish to create an environment that promotes learning should start with themselves. They should share their own mistakes and the lessons they have learned in order to develop the feeling of trust within the corporation. They must further turn this into a common learning process and create a transparent environment that will set the stage for continuous learning. Leaders should ensure that the corporate culture embodies an understanding that “To win we have to make calculated experiments,” rather than “We should do nothing for fear of making a mistake.”

Professional diligence also requires that the management discloses mistakes and problems in a timely fashion. This may be unpleasant, but it builds trust and helps build a continuous learning culture. If the management has valid concerns, the board has to know about them. Mutual trust between the board and the management also requires the acceptance and the internalization of the separation of management and governance rights.

Sustainability issues are generally long-term issues that need long-term attention.36 Therefore, the board should ensure that the efforts are sustainable to make a sustainable impact. Hence, sufficient financial resources, organizational/human resources, and intellectual resources should be allocated to address the key sustainability issues.

Deployment and Learning

Both the competitive pressures and the increasing expectations of the stakeholders call for continuous learning and development from the corporations. Therefore, the board needs to take action to ensure that the sustainability agenda of the corporation is an integral part of the culture and its systems assure learning and continuous improvement. For this purpose, the key sustainability issues need to be identified and incorporated into strategies, policies, objectives, and associated management systems with a particular view toward value-creation opportunities.

Another key concern is the deployment of the board's sustainability priorities throughout the organization. A successful deployment program requires establishing a framework for effective communication and learning for the employees and the members of the supply chain; incorporating sustainability issues into hiring and remuneration policies as well as supplier identification processes (having appropriate incentive systems); establishing clear guidelines and remedies for those who fail to follow the corporation's sustainability standards; and making sure that the management information systems provide for adequate, appropriate, and verifiable data on key sustainability priorities.

Internal control systems, external reviews, stakeholder engagement processes, and compliance requirements should all be utilized for continuous learning opportunities, rather than as tick-the-box compliance requirements.

Transparency and Reporting

Emerging global standards for sustainability reporting, including the GRI and IIRC, are gaining broader acceptance, but the field of sustainability reporting is still open to experimentation with new approaches. For example, the government of New Zealand is publishing a balance sheet for the assets and liabilities of the government. Despite being a leading example for governments elsewhere, this public balance sheet approach has significant room for improvement, particularly in incorporating environmental assets and liabilities. An Istanbul District Municipality, Kadıköy, adopted integrated reporting as a local government entity.37 On the corporate side, Puma has come up with another path-breaking example by including the environmental costs of all its supply chain in its sustainability reporting.

What gets measured gets improved. Although far from perfect, these examples set the stage for other organizations to rethink how far transparency and reporting can go to help accelerate the speed of learning.

Conclusion

Sustainability is a balanced pursuit of three goals mutually: ecological health, social equity, and economic welfare. Sustainable behavior calls for nature's functions and diversity not to be systematically impoverished by human intervention and resources to be utilized fairly and efficiently in order to meet basic human needs globally, including the preservation of the opportunities for future generations to continue to improve quality of life.

The main purpose of ethical and moral behavior is to constrain the individual's short-term interests for the long-term survivability of humanity (the community/future generations).38 Therefore, sustainability is firmly engrained in ethical and moral behavior.

Hence, all organizations and as their stewards, boards of directors, are responsible for a sustainable future. This chapter summarizes the key responsibilities and activities for boards of directors to fulfill their fiduciary, ethical, and moral responsibilities for a sustainable future.

Responsible boards are critical not only for the survival of the corporation that is entrusted upon them, but also for the survival of the human kind and our planet for a sustainable future. In order to properly fulfill their sustainability responsibilities, boards need to address and reflect upon, at a minimum, the following 35 questions.

Appendix

About the Author

Dr. Yılmaz Argüden is a leading strategist, advisor, and board member of major public and private institutions, and NGOs. He is the founder and chairman of ARGE Consulting, a globally recognized management consulting firm based in Istanbul. ARGE has been recognized at the European Parliament as one of the best three companies shaping the future with its commitment to corporate social responsibility. ARGE Consulting is the first Turkish signatory of the UN Global Compact and has served as the B20 Knowledge Partner for Governance & Sustainability.

He is also the chairman of Rothschild investment bank in Türkiye. He has served on the boards of more than 60 companies in different jurisdictions. He is an adjunct professor of Business Strategy at the Bogazici University and the Koç University; an author of numerous books and a columnist focusing on business, strategy, and governance issues.

As a social entrepreneur he has founded and led numerous NGOs; initiated the National Quality Movement. As the elected global chair of the Local Networks he represented 100 National Networks on the Board of the UN Global Compact, the world's largest sustainability platform.

He is a renowned governance expert and served as a member of the Private Sector Advisors of the IFC's Corporate Governance Group, and as the vice-chairman of the Governance Committee of the Business at OECD. He is also the chairman of the Trustees of the Argüden Governance Academy Foundation.

He has a BS degree in industrial engineering from the Bogazici University, where he received both the Top Graduating Engineer Award and the President's Prize for Student Leadership. He received his PhD in policy analysis from the RAND Graduate Institute with General Distinction. He was a member of the high school and university basketball teams that won the National Championships in three consecutive years and served as the vice-chair of the Turkish Basketball Federation. He is an Eisenhower, Fulbright, NATO, and Tubitak fellow; and a recipient of numerous leadership, distinguished citizenship, and career awards. He was selected as a Global Leader for Tomorrow, by the World Economic Forum for his commitment to improve the state of the world. www.arguden.net

Notes

- 1. The author wishes to thank Sir Mark Moody-Stuart, former chairman of Royal Dutch Shell, Anglo American, and Hermes Equity Ownership Services; Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever; Alan Clark, CEO of SAB Miller; Jochen Tilk, CEO of Potash Corp.; Damian Gammell, CEO of Anadolu Efes; Paul Gagné, former CEO of Avenor Inc and former chairman of the Canadian Pulp and Paper Association; Matt Fullbrook, manager of Clarkson Centre for Board Effectiveness at the Rotman School of Management; Gizem Argüden from McKinsey, and Dr. Erkin Erimez from ARGE Consulting for their review and constructive comments on an earlier draft.

- 2. Sustainability's deepening imprint: McKinsey Global Survey, July 2017.

- 3. Y. Argüden, “Boardroom Secrets: Corporate Governance for Quality of Life,” Palgrave MacMillan.

- 4. Joseph F. Johnston, Jr., “Natural Law and the Fiduciary Duties of Managers,” Journal of Markets & Morality (2005).

- 5. John H. Walton, “Deuteronomy: An Exposition of the Spirit of the Law,” Grace Theological Journal (1987).

- 6. The Conference Board, “Sustainability in the Boardroom,” DN-008, June 2010.

- 7. See, for examples of cases where the legal courts underscored the importance of assessing the impact on key stakeholder relations of a business decision made in the context of hostile takeovers and shareholder-instituted derivative actions: Unocal Corp. Mesa Petroleum Co., 493 A. 2d 946, 955 (Del. 1985), discussing how boards should consider the impact on constituencies other than shareholders when analyzing the reasonableness of defensive measures; and Paramount Communications, Inc. v. Time Inc., 571 A. 2d 1140, 1153 (Del. 1989).

- 8. For example, 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. §1715. In general, see Kathleen Hale, “Corporate Law and Stakeholders: Moving beyond Stakeholder Statutes,” Arizona Law Review, Vol. 45, 2003, p. 829.

- 9. Delaware Code Annotated, Title 8, Section 102(b) (7), permitting the use of clauses in the certificate of incorporation (therefore approved by shareholders) to insulate corporate directors from monetary liability for any action arising from a breach of their duty of care. Exculpatory clauses provide more freedom and leniency to directors in their decision-making capacity, and encourage them to take strategic risk.

- 10. “Pursuit of Social Investments,” The Conference Board, Director Notes No. DN-002, January 2010.

- 11. “Rebuilding Corporate Leadership: How Directors Can Link Long-Term Performance with Public Goals,” Committee for Economic Development, 2009, available at www.ced.org.

- 12. UNFCCC: The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is an international environmental treaty negotiated at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro from 3 to 14 June 1992, then entered into force on 21 March 1994.

- 13. The author was one of the participants of the World Economic Forum's Davos meetings where Kofi Annan, the seventh Secretary General of the United Nations, made this speech and called business and civil society leaders to action. Dr. Argüden became the first Turkish signatory of the UN Global Compact both as a business (ARGE Consulting) and an NGO (National Quality Association) leader.

- 14. Perhaps partly because of the resource limitations of the UN Global Compact, and its limited ability to apply remedies. Necessity is the mother of innovation.

- 15. In some cases, regions, such as Gulf countries or Scandinavian countries.

- 16. http://www.argudenacademy.org/docs/good-governance-building-sustainable-societies-active-engagement-and-responsible-behaviour.pdf?utm_source=Article+Share-+ENG&utm_campaign=d2eb07b5ed-Corporate_Governance:Bulletin_Winter_2015&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_b1a29d0b04-d2eb07b5ed-178886077.

- 17. IoDSA (2009) King Report Governance for South Africa 2009.

- 18. ARGE Consulting acted as the B20 Knowledge Partner for Governance & Sustainability, http://integratedreporting.org/news/g20-a-step-towards-inclusive-growth-and-sustainable-development-for-all/

- 19. Equator Principles website, www.equator-principles.com.

- 20. Adams and Larrinaga González, 2007, “Engaging with organizations in pursuit of improved sustainability accounting and performance,” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Volume 20, Issue 3.

- 21. See “Responsible Leadership,” Sir Mark Moody-Stuart (2014 Greenleaf Publishing), for excellent examples of how boards really deal with key sustainability issues.

- 22. Sometimes may also be called “Corporate Responsibility Charter.”

- 23. If there is a specific committee assigned for this responsibility, the Charter may cover the relevant committee's responsibilities.

- 24. William McDonough and Michael Braungart, “Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things,” North Point Press, 2002.

- 25. Ocean Tomo, Intangible Asset Market Value—2010, 2011, www.oceantomo.com/media/newsreleases/intangible_asset_market_value_2010.

- 26. Dr. Argüden et al. “Entelektüel Sermaye,” ARGE Consulting Publications No: 7, 2005.

- 27. See, Neil Jeffery, “Stakeholder Engagement: A Road Map to Meaningful Engagemen,” Doughty Centre, Cranfield School of Management, July 2009, for pros and cons for each.

- 28. Edward E. Lawler III and Christopher G. Worley, “Management Reset: Organizing for Sustainable Effectiveness” (Jossey-Bass, 2011).

- 29. “Regard the other, as you regard yourself,” by Yunus Emre (1240–1321), the famous Turkish poet and Sufi mystic.

- 30. Toyah Miller and Maria Del Carmen Triana, “Demographic Diversity in the Boardroom: Mediators of the Board Diversity-Firm Performance Relationship,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 46, No. 5, 2009, pp. 755–786.

- 31. Dr. Argüden, “Diversity at the Head Table,” Private Sector Opinion #19, International Finance Corporation, 2010.

- 32. Dr. Argüden, “Global Boards Help Make Companies Global,” HBR Blog November 2011.

- 33. Dr. Argüden, “Why Boards Need More Women,” HBR Blog Network, June 2012.

- 34. The committee may also be named Responsibility Committee; Safety, Health, Environmental Protection, and Stakeholder Engagement Committee; or the responsibility may be assigned to the Audit or Risk Committees.

- 35. Dr. Argüden, “Right Reward for Right Performance: Aligning Executive Compensation with Good Governance,” International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, Vol. 10, 2013.

- 36. Therefore, the sustainability of effort is critical as in the Turkish saying, “What breaks a rock is not the strength, but the continuity of water flow.”

- 37. https://integratedreporting.org/news/municipality-integrated-reporting-model-the-famous-istanbul-district-kadikoy-adopts-integrated-reporting/.

- 38. This definition is based on Ege Cansen's speech on “Ethics and Morality” for the Arguden Governance Academy, January 2014.