19

Responsive Governance in a Digital World: The Need to Up-Skill

Dr. Elizabeth Valentine

Chief Information Officer of Massey University, New Zealand; and Adjunct Research Fellow and Teaching Fellow at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Dr. Steven De Haes

Dean of Antwerp Management School and Professor of Digital Strategy & Governance at Antwerp Management School and the University of Antwerp

Dr. Anant Joshi

Assistant Professor of Information Management at the Department of Accounting and Information Management at Maastricht University's School of Business and Economics

Introduction

Given the speed of change and advent of emerging technologies, digital transformation is a topic boards are aware of and increasingly grappling with. Making quality and timely decisions during rapid technology change is underpinned by individual competency across the board. A token tech-savvy director is not enough.

While fear of cybersecurity breaches is driving action, the strategic issues of competing in a digital world are driving longer-term competitiveness and corporate sustainability. Technology risk and technology-enabled opportunity are two sides of the same coin, and both need to continue to be an active part of director and senior leader dialogue.

With an ever changing digital landscape, a blend of governance approaches helps board members to build capability in addressing technology challenges. The aim should be for a mix of good governance practices as well as those driven by the need for speed. This means considering how to become agile and flexible, as well as compliant.

Because individual director competency impacts the collective competency of the board, a lack of sufficient Enterprise Technology Governance (ETG) capability is potentially adding to risk at the top. Valentine (2016) suggests that even the most common director governance capabilities—for example, finance, legal, strategy, marketing, operations—are in need of a refresh to ensure these occupational skillsets are relevant in a digital world. While awareness appears higher than it has been, many boards are still behind when it comes to ETG.

In this chapter, we first spell out digital transformation and the need for speed for boards. Second, we define six areas of IT governance risk and suggest up-skilling all board roles. This will help directors and non-IT officers to build the necessary capabilities to respond rapidly to both IT risks and opportunities in a competent way. Third, we provide detail of three competency areas for boards to assess and develop. Fourth, we explore the emerging topic of agile governance and rapid risk response methods in parallel with more traditional methods. Finally, we suggest five practical steps to take to become more responsive and to remain relevant, no matter what your core skillset is as a director.

Digital Transformation

What Is Digital Transformation?

Information, communication, and operational technologies and applications are commonly referred to as digital technologies. Increasingly, digitized ways of engaging and transacting are the accepted and expected way of doing business and transacting.

Digital transformation is the significant modification of how an organization manages business. This includes changing a wide range of organizational activities, processes, competencies, and models to fully leverage the innovation and opportunities offered by a mix of digital technologies and applications. The impact of emerging technologies together with the ways of gathering and analyzing information is driving the need for transformation. This is occurring universally across business, government, and nonprofit organizations, and society as a whole.

George Westerman, principal research scientist with MIT Sloan and a digital transformation thought-leader, describes digital transformation being evident when companies use technology to radically change the performance or reach of the enterprise. According to Westerman, companies are driven by disruption in two areas.

First, disruption is driven by existing competitors. Here, changes in competitive positioning are evident in improved margin and through cutting operating costs. These competitors enter new markets or open up new channels afforded by radically changing how the firm uses information and technology.

Second, disruption occurs through the rise of new competitors. This has happened across nearly all industry sectors. Here, newcomers gain advantage through system, product, and service innovation to win new customers and create new markets.

There's no getting away from the fact that technology is transforming how we work, live, play, and interact as whole countries, counties, cities, towns, organizations, groups, and individuals. And it's happening faster than many can conceive or cope with.

The Need for Speed Is Being Driven by Your Customers and Stakeholders

Alongside the disruptive impact of emerging technologies on companies, another key aspect of digital transformation is the rapid rise of tech-savvy customers and stakeholders, including shareholders.

Digitization is occurring across large and small organizations in the public, not-for-profit, and private sectors. Further, cloud computing and mobile has facilitated the extraordinary and disruptive rise of big data analytics, tablets, smartphones, and social marketing. Industry commentators and researchers alike predict that this nexus of forces will continue to revolutionize the manner in which enterprises of all types and sizes around the world conduct business.

With digital disruption and access to unprecedented amounts of know-how, customer and stakeholder expectations and even technical knowledge often exceeds what firms are able to deliver. Further, how firms organize people and systems to meet increasing customer demands is changing. The boundaries between office and work, customer and stakeholder are morphing, merging, and converging very rapidly.

Figure 19.1 illustrates how cloud, mobile, social, and big data technologies have come together to create information and technology-enabled opportunities and risks. This combination of technology has facilitated the rapid development and implementation of a dizzying array of technologies and applications. The pervasive and disruptive nature of these technologies has precipitated the largest change in the way people live since the industrial revolution. The effects are global and affect all industries in a range of ways, no exceptions.

Figure 19.1 illustrates a combination of the affordances of technology and customer power, globalization, and the use of information and technology for competitive advantage. This dynamic combination of influences is pervasive, disruptive, and impacting at breakneck speed.

FIGURE 19.1 Nexus Technologies Driving the Need for New Competencies and Speed

The need for digital transformation is about remaining relevant in this environment. It requires a fundamental rethink about how boards and executives analyze risk and opportunity, and how they strategize, monitor, and govern information and technology in organizations. These are the three areas of ETG competency we discuss later in the chapter.

Never before have boards and senior executives needed to understand what ETG is. And this means new understanding of ETG and new or expanded individual governance capabilities.

What Is Enterprise Technology Governance?

Enterprise Technology Governance provides the means by which the board and senior executives fulfill their duty-of-care responsibilities when making business and Information and Technology2 (IT) decisions. ETG includes the alignment and oversight of enterprise IT with the organization's business strategy, structure, systems, policies, and governance processes. Good practice ETG leads and facilitates a culture of data-driven decision-making and seeks to minimize IT risk throughout the enterprise. ETG creates value by optimizing stakeholder engagement and strategic investments, and in deriving returns from new and old sources (updated from Valentine, 2016.)

This definition centers on clarifying the specific enterprise-wide roles and accountabilities of directors in governing information and technology. The board directors and senior executives have both individual and collective duty-of-care responsibilities to govern both information and technology assets. However, the definition also includes the aspirational leadership nature of the board's role in building a data-driven, tech opportunity, risk-aware culture, and directing strategy and value creation from investments. In other words, IT competent boards can build stronger organizational capabilities through digital transformation.

Steven De Haes and Wim Van Grembergen (2015) have long asserted that ETG and corporate governance have converged to become one and the same, suggesting that IT governance is an integral part of corporate governance exercised by the board. The board oversees the design and implementation of processes, structures, and relational mechanisms in the organization so that both business and IT people execute their responsibilities in support of business/IT alignment and the creation of business value from IT-enabled business investments.

The key is how IT governance can be deployed as part of overall governance using processes, structures, and relational mechanisms—common, well understood mechanisms—that are already in place, but from an integrated and digital worldview.

ETG structures can be seen as a blueprint of how the governance framework will be organized. ETG structures include organizational units and stakeholders as users. Structures are also the mechanism for assigning roles and responsibilities and provide the framework for formal communication channels. So, structures should also define and delineate governance and operational roles to connect board responsibility with operational responsibility for identifying and appropriately escalating IT risk. In this way, structure facilitates a “rapid-risk-response” (Valentine, 2016) approach to cybersecurity, for example. Governance structure needs to also support IT decision-making and to facilitate contacts between business and IT management and the board when decision-making and governance oversight are required (e.g., IT steering committees or cross-functional IT project teams).

ETG processes refer to the formalization and institutionalization of strategic IT decision-making and IT monitoring procedures. ETG processes can be as simple as project management processes or a formal part of business process. How work is planned, conducted, monitored, and reported through process ensures that daily behaviors are consistent with policies as well as strategic goals. Processes are integral to reporting and provide input back to decisions (e.g., portfolio management). As we discuss later, ETG processes can be traditional (such as management by objectives/waterfall methods) or more agile.

Finally, ETG relational mechanisms are about the active participation and collaborative relationships required to compete and prosper. They are people-oriented, existing among corporate executives, IT management and service suppliers, business management, and key stakeholders. Relational mechanisms can include committees, project assignments, stand-ups, announcements, advocates, channels, and education efforts.

FIGURE 19.2 Structures, Processes, and Relational Mechanisms for IT Governance

Source: De Haes & Van Grembergen, 2015.

They can also include human-centered design approaches such as collaborative design or codesign, which involves a range of stakeholders including customers. Some examples of structures, processes, and relational mechanisms are provided in Figure 19.2.

Structures and processes are the formal design and communication channels that support a firm's work, whereas relational mechanisms are often informal and less structured. However, relationship-based engagement with internal and external stakeholders can make or break a project at all stages; same with client and supplier relationships. Relational mechanisms are determined by culture and the often taken-for-granted practices which influence how people interact to fulfill their roles. This happens at all levels including within boards, executive, and management teams.

The challenge in building skills during digital transformation is in developing change and relational capability at all levels, including the board. It's not enough to invest in digital transformation from a technology perspective. Change capability will determine whether investment pays a return and transformation is realized. Here it can be useful to consider structural, process and relational impacts as a checklist for change planning. In particular the chief executive and board must pay attention to whether poor supplier performance or project slippage is being accurately reported through operating and project reports.

While these simple steps might not sound so different, what has changed is the operating context. In a significantly changing digital world, we suggest that it's foolhardy for a board to state that they don't have a role in governing information and technology strategy, structures, policy, processes, risks, stakeholders, and investment. Change means building new skills and capabilities.

Disruptors Are Innovative and Agile; They Can Come from Unexpected Places

So far we have introduced a complex digital world that boards must comprehend to be capable of making quality judgments as directors. There is a strong and growing link between change leadership, technology investments, and increased competitiveness. As a result of digital technologies, any company's unique business processes and business models can now be multiplied with much higher fidelity across the organization, by embedding them in enterprise IT. This is a significant competitive risk in less capable hands. It is an opportunity in a tech-savvy board's hands. Innovators with a better way of doing things can scale up with unprecedented speed and dominate an industry (McAfee & Brynjolfsson, 2008).

The bottom line is, when it comes to disruptors such as Uber and Amazon, competition is already coming from new, aggressive sources. The strategic assimilation of a wide range of digital technologies is accelerating worldwide, including from third-world countries. Here, technologies are enabling whole cities, sometimes countries once considered backward, to leapfrog over their first-world counterparts.

These disruptors are lean and agile. They simply bypass unsustainable models of doing business and legacy infrastructure development that older, developed countries have already passed through. A digital start-up can literally plug into the developed world's global web and cloud infrastructure, often at significantly lower cost. There are examples of cities such as Bangalore, Mumbai, Dhaka, Shanghai, and Lagos rising directly from rural, agrarian economies to become the futuristic, sustainable, knowledge-driven city-states they are today.

Traditional Versus “Agile” Governance

While agile has become a bit of a buzzword, it's also a useful description of the type of rapid, flexible, customer-centered governance required at board level in a digital world.

The challenge is to meet both regulatory requirements for good governance practice while at the same time having the capability to make decisions and proceed, at pace, when required. We define agile governance as:

Agile Information and Technology Governance utilizes structures, processes and relational, user-centered design to define user needs and implement information and technology infrastructure to support strategic business achievement. Non-IT business units and technical specialists are involved in co-designing and implementing information and technology for competitive advantage and business effectiveness. The approach is applied at all levels, with the board providing oversight. The focus and methods are part of the culture: they're user-centered, utilize the principles of the Agile Manifesto and facilitate rapid risk response.

Based on Luna et al. (2010), Table 19.1 compares the focus, language, relationships, and predominant pace of the different approaches: IT management, traditional governance, operational IT governance, agile methods, and agile IT governance.

Is it a matter of traditional versus agile? We suggest not. Table 19.1 introduces the interrelationships between these areas of practice. The table highlights the general characteristics of a range of methods. However, as a developing approach, we suggest using agile principles, values, and best practices alongside more traditional methods (Valentine, 2016). This is more likely to ensure good practice processes for planning and reporting are supported by user-centered and collaborative design and agile approaches to construct a fit-for-purpose information and technology Agile Governance method that works for your organization.

However, whatever approach is used, a fresh approach is required to board governance competencies. This fresh approach should underpin planning and decision quality in a digital world. The future success of digital transformations may rest on how well firms learn to lead, govern, and use the information and technologies which have infiltrated, amplified, distracted, enriched, and complicated our lives.

Table 19.1 Traditional and Agile Management and Governance Methods Compared

| Aspects | Traditional IT Management | Traditional Board Governance | Operational IT Governance | Agile Methods | Agile IT Governance All Levels, including the Board |

| Focus | On technology; keeping the business running Often inward looking |

On overseeing the business with a focus on shareholders | On the business and IT projects Can be both inward and outward looking | On the customer and ICT/IT projects Both inward and outward looking | On the business, customers, and other stakeholders such as supply-chain partners |

| Language / orientation | Reliability; Technology specialists; can be strategic business partners; waterfall methods; technical and project detail |

Reliability; Business & governance; plan driven; approval-based; COBIT5 |

Reliability & flexibility Business, operations; waterfall projects; Prince2, PMBoK, ITIL, TOGAF |

Targeted; flexible Use cases; user profiles; minimum viable product; just enough documentation; business-centric; close to the customer; Kanban Agile; Lean | Reliability and responsiveness Business, customer and technology centered;A combination of COBIT5 & Rapid Risk Response methods |

| Relation to customers and the rest of the business | Limited, can be too distant from customers / wider stakeholders | Limited direct contact with customers, but increasing proactive contact with shareholders | Participative; increasingly seeks to be a business partner | Close; smart use of collaboration and codesign tools in evidence; drives continuous improvement processes | Close and participative: codesign informs and enables agility; rapid risk response approaches are part of structure, culture, systems, and relationships |

| Pace / cycle times | Usually slow | Slow; reporting by exception | Detailed and complicated; often slow as focus is mainly on waterfall methods | Iterative, empirical, and usually fast; frequent delivery of working models to test | Measured and responsive as required |

Why IT Governance Capability Is Necessary Across the Board

To establish if there is a need for ETG competencies within boards, it is essential to understand the role and responsibilities of corporate governance. Acknowledging the impact of digital disruption on a global scale, and importance of digital leadership for companies, it is reasonable to assume that ETG as a component of corporate governance should be well understood. Especially, the key players like the board of directors and senior executive must make appropriate efforts to gain ETG competence.

Yet, as technology has become further and further embedded into our work and private lives, it appears that ETG competence remains the “elephant in the boardroom” for more than 75 percent of boards. As recently as 2014, NACD reported less than 20 percent of corporate boards worldwide having confidence that they have technology-capable directors.

How Bad Is the Board ETG Capability Problem?

Corporate governance is the overall rigorous supervision of management that ensures the work of the organization is done competently, with integrity, and with due regard for the interests of all stakeholders (Norfolk, 2011). It is easy to assume that this definition encompasses board ETG capability. Any such assumption, however, is flawed. Directors must improve their ETG capability.

A majority of boards and senior executives know that technology is critical to their enterprises. However, only a small number of boards worldwide have made the transition from an almost mono-focus on finance and legal capability as a proxy for corporate governance, to incorporating digital leadership into the new mix of the board's structure and capability profile (Valentine, 2016). In failing to understand their information and technology governance leadership roles and the need for capable oversight, many boards continue to fly blind (Carter & Lorsch, 2004), and so risk is increased.

A Skill Shortage at the Top

The problem is that there is a skill shortage at the top. Your organization does not need to be a multinational for capable ETG to be a requirement in your board and senior leader team. And, you're not alone. Right around the world, directors vary significantly in their personal competency and collective capability to provide effective information and technology governance oversight and digital leadership.

Strong IT knowledge, skills, and experience, that is, competency and capability within the board and management, increases opportunities and can improve bottom-line results. On the flipside, lack of capability can significantly increase risk across six areas. More on this in the next section.

Two landmark court cases illustrate the significance of the requirement for board ETG capability. In 2014, the entire board and senior executive of both Target US and Wyndham World Wide were sued for breach of duty of care (United States District Court, 2014a, 2014b) after cyberattacks. We suggest that even though both cases were eventually dismissed, a lack of ETG capabilities at the top can have very serious consequences on firm reputation. But, barriers remain to build ETG capability at the board level.

The reluctance of boards to include IT governance competencies in the boardroom might be because of confusion on the term “IT governance” (Valentine & Stewart, 2013). Many board members do not perceive IT governance as a topic that the board should take care about, but rather a topic associated with the IT department (Butler & Butler, 2010; Steven De Haes & Wim Van Grembergen, 2015; Parent & Reich, 2009). However, the board's role in providing governance oversight of IT matters differs significantly from that of IT management. That is, the board should consider IT from a perspective of strategy, risk, and control rather than from a technical and operational point of view. Accordingly, board members' IT expertise or experience does not have to be of an extremely technical nature, but should entail strategic, integrative, and aligning aspects.

Case Study: How Agfa-Gevaert Increased Their Board IT Governance Capability3

Contrary to many organizations, the level of IT expertise is quite high at the board of Agfa-Gevaert. However, this does not mean that every board member holds a technical diploma or a CIO position in another firm. There are two ways in which Agfa's board members have built their IT expertise.

First, there are two board members with an IT-related education and professional background. One holds a master of sciences in electronic engineering and computer sciences. On top of that, he founded an organization that provides software in the field of online banking and regulatory financial reporting. He is also the chairman and CEO of another e-finance company. As such, he has deep and broad IT knowledge. Another board member graduated as an engineer specializing in electro-technology and mechanics with a PhD degree in electronics. In the past, he had served as the chairman of a technology advisory group for the European Commission. He is also a member of the executive board, COO, and advisor to the chairman of the board of directors of a global telecommunication company.

Second, several members of the Agfa-Gevaert board have gained a certain level of IT expertise, experientially. Their expertise is not because of their educational background but because they were involved in large IT projects or active in an industry that is highly dependent on IT.

A good example is the CEO of Agfa-Gevaert. He worked in a global telecommunications company from 1978 until he joined Agfa-Gevaert in 2008. Here he was also involved in a merger, which required him to dig deep into the processes and IT systems of both organizations. One other board member worked in this telecommunication company as well. In addition, another board member was CEO of a large banking and insurance company, a sector where IT is crucial. Hence, as the telecommunications and banking industries rely heavily on IT, these directors became familiar with IT-related decision-making.

Another board member who joined the board of Agfa-Gevaert in 2015 acquired IT experience in a different manner. From 2004 until 2010 she was a member of the European Commission with responsibility for information society and media. During that time, she was involved in different IT-related projects. One of these projects was the launch of the i2010-initiative, which entailed a five-year strategy to boost the ICT competitiveness of Europe. She also initiated the “eGovernment action plan” to stimulate the digitalization of public administrations. This is exactly the kind of IT-related strategic experience and exposure to IT decision-making a board needs. Table 19.2 summarizes the two types of professional development in IT governance that has created a well-rounded ETG competency profile within the Agfa-Gevaert board.

Table 19.2 Explicit IT Education and Relevant IT Strategy and Decision-Making Experience

| IT expertise at board level | ||

| Board members with explicit IT expertise | 1 | Master of sciences in electronic engineering and computer sciences Founder of a software development company CEO and chairman of an e-finance company |

| 2 | Engineer specializing in electro-technology and mechanics PhD in electronics Chairman of a technology advisory group for the European Commission Member of the executive board, COO, and advisor to the chairman of the board of directors at a telecommunications company | |

| Board members involved in IT-related projects or active in IT-dependent industries | 3 | Member of the executive committee and vice-chairman of the board of directors at a telecommunications company |

| 4 | CEO and member of the executive board at a telecommunications company | |

| 5 | Former CEO of banking and insurance company | |

| 6 | Member of the European Commission with responsibility for the information society and media | |

In conclusion, six of the seven members of the board of Agfa-Gevaert have IT expertise either building through a technical or a business focus. This high level of IT expertise is an enabler of board-level IT governance at this organization. Whenever an IT topic is raised during a board meeting, there is a certain level of understanding among the board members.

The example of Agfa-Gevaert shows us that to increase the level of IT expertise in the boardroom, one does not only have to rely on directors with an IT-related educational background. Directors used to IT-related decision-making and control from a business perspective are strong contributors in reducing IT risk, spotting new IT-related opportunities, and in general help make the board more IT savvy.

Benefits of Boards Building Information and Technology Leadership Capability

Having “tech-savvy” directors and senior executives can result in significant financial and competitive advantages. Turel and Bart (2014) concluded that, “High levels of board-level IT governance, regardless of the strong need of reliable or innovative IT, increased organizational performance.” However, Fitzgerald, Kruschwitz, Bonnet, and Welch (2014) found that only 15 percent4 of the organizations studied demonstrated information and technology maturity. These firms demonstrated IT maturity by providing competent and comprehensive IT investment leadership, and IT change and transformation leadership. And these mature firms consistently outperformed their peers financially by 9 percent, were up to 26 percent more profitable, and enjoyed up to a 12 percent greater market valuation. At the level of the enterprise, current and future value creation through digital transformation was driven from the top. These results occurred across all industry sectors, without exception.

The above-mentioned study included the board and executive as a key success factor, suggesting that they provide a clear and transformative vision of a digital future together with careful governance and multi-stakeholder engagement. Moreover, the board and executive understood how to make prioritized investment in new digital opportunities, at the same time ensuring a secure and up-to-date infrastructure. Through this combination of visionary change leadership, focused investment, and wide engagement the board and executives developed a digital culture that helped the organizations embrace and leverage rapid technological change. By competently observing, strategizing, investing, and carefully coordinating digital initiatives, such firms continuously advance their digital competitive advantage (Westerman, Bonnet, & McAfee, 2015).

However, failure to build strategy-matching competencies in boards (Leblanc & Gillies, 2005), which include ETG, can have serious consequences. Lack of capability can lead to increased technology and business risk, missed strategic opportunities, or a failure to integrate and leverage digital investments. Ultimately, such incompetence can lead to value destruction. At this end of the spectrum, those that do not build capability risk being sued or going out of business. Unfortunately, examples of these winner/loser extremes are increasing.

Winners and Losers

In this rapidly changing and increasingly uncertain digital world, organizations, large and small, private and public, face new opportunities and risks. Amazon, Apple, Google, Spotify, FaceBook, Expedia, AirBnB (USA), Huawei (China) Uber, Burberry, and Tesco (UK) have seized the digital leadership space. Many have developed disruptive approaches, such as Apple's development of the App Store. Others such as Uber have deployed apps and social media in innovative ways to disrupt their industry sector.

Technology and digitization is disrupting once very stable industries and creating whole new business models (think Uber5 and Airbnb6). For example, solar energy generation and the Powerwall from Tesla Motors are significantly and rapidly disrupting current models of domestic and commercial electricity generation and transmission. Disruption in the clean energy sector is occurring along with the rise of “prosumers”—those customers who both consume and generate (Rathnayaka, Potdar, & Ou, 2012). In some sectors such as engineering and manufacturing, cycle times are significantly shortening, and new, competitive products are being developed, often at a fraction of the original cost (think digital printing in everything from whole houses to limb prosthetics).

Other organizations have not fared as well. Once considered technology leaders, an increasing list has either gone out of business or have lost significant market value because they failed to keep up with some aspect of technology opportunity or risk, or both. These companies include Kodak, EMI, Nortel, Barnes & Noble, HMV, KMart, Sony, Sears, Target (USA), and AOL. “In most instances, these firms made no massive or sudden blunders and they are often still in the textbook Hall of Fame even as their erosion had become marked and even irreparable” (Keen & Williams, 2013, p. 643). Such outcomes, or even poor or reduced capability in the oversight of digitally intense change, call into question the role of the board of directors, their corporate governance, and specific competency in governing enterprise technology. In the review of most high-profile IT project failures, there is a common question: Where was the board?

The significance of the change in board ETG capability required is graphically illustrated by a tipping point reached in 2014 involving cybersecurity breaches. Two landmark court actions were filed in the United States of America. In both cases, entire boards of directors as well as individual senior executives of Target USA and Wyndham Worldwide Corporation were charged with breach of fiduciary care (United States District Court, 2014a, 2014b).

The Case of Target USA, December 2013

In March 2014 Bloomberg Business Week reported a serious cybersecurity breach, reporting that Target USA's board and management effectively stood by as more than 40 million credit card numbers and 70 million addresses, phone numbers, and other pieces of personal information “gushed out of its mainframes.” Gregg Steinhafel, Target's chairman, president, and chief executive officer, was a 30+-year employee. Three alerts were sent to Target several weeks before the cyberattack and were ignored. This occurred despite the company having six months earlier installed a $1.6 million malware detection tool also used by the CIA and the Pentagon.

In January 2014, a Target shareholder filed a “verified shareholder derivative complaint” with the Minnesota District Court. Target Corporation's board and key management were sued for breach of fiduciary duty and waste of corporate assets (United States District Court, 2014a). By March 2014 Target had already faced more than 90 lawsuits filed by customers and banks for negligence and compensatory damages. That was on top of other costs estimated to run into the billions. For example, Target spent $61 million during February 2014 responding to the breach while holiday shopping period profits fell 46 percent from the same quarter in 2013, with the number of transactions suffering the biggest decline since the retailer began reporting these statistics in 2008. The case for breach of fiduciary duty was ultimately dismissed in 2016 after a 21-month investigation. Target's 10-Q report reported $291 million of cumulative expenses related to the case for the period to April 2016.7 While this level of expense is high, it should be noted that this figure does not include indirect costs such as loss of income and reputation.

To summarize so far: Boards and senior executives know technology is essential to the future of their organizations. However, too few have stepped up to competently lead and govern the digital transformation required to remain relevant and competitive going forward. While technology is rapidly becoming one of the largest areas of corporate expenditure, boards are continuing to delegate or ignore their role in technology governance. To put this lack of oversight in perspective, it would be unthinkable for a board to treat financial or legal matters with the same lack of competent oversight. The consequences of this approach are emerging as significant and severe.

At the other end of the spectrum, those organizations that build enterprise information and technology governance competency and capability, and demonstrate digital leadership are more likely to thrive and survive going forward. What can boards do to govern competently in an area they appear to know so little about? The rest of this chapter provides ideas and suggestions, starting with seven areas of IT risk.

Seven Areas of ETG Risk Boards Need to Know About

In this section, we summarize seven areas of IT-related risk. Table 19.3 provides a series of questions your board and senior leaders can use to evaluate and prioritize your organization's current areas of risk exposure. You can also use this table to help evaluate your ETG maturity as well as beginning an evaluation of your ETG capability profiling.

As shown in Table 19.3, the areas of IT risk help demonstrate that board ETG capability needs to be broad. For example, being hacked is usually a result of risk in a range of areas: hacking is seldom only about information security. It is usually about a combination of unidentified risk factors, as was the case with Target USA.

Table 19.3 Information and Technology Risk and Key Considerations

| Area of IT risk | Key Considerations |

|

Does your organization have a vision of a digital future? Does your board and executive have a clear understanding of how technology is disrupting your sector, industry. or even similar-sized organizations? Can your board and executive identify new business models that could add to strategic and competitive value or risk? Are your organization's business and IT strategy aligned and integrated? Does your strategy contain a comprehensive overview of all major stakeholders (shareholders, supply and alliance partners, regulators, management, and staff) and the ways in which technology can enhance communication and engagement with them? Does your board have a current understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of current technological engagement with stakeholders (and preferably each stakeholder's views on this)? |

|

Is the board able to oversee IT acquisition, implementation, maintenance, and disposal to meet the board's fiduciary, regulatory, compliance, ethical, contractual, and legal obligations? (ISO/IEC, 2008) How does the organization define key security objectives to ensure they remain current and relevant? Is there a cohesive yet flexible, prioritized, enterprise-level IT plan to keep IT assets and core software up-to-date? What type, level, and priority of IT risk is there in the current or proposed enterprise IT design (architecture)? Does the current or future enterprise IT design (architecture) support or hinder strategy achievement, business performance, and compliance? How does the organization take advantage of cloud computing and still protect our information assets? |

|

Here are some considerations expanded from the IT Governance Institute's (ITGI, 2006) guidelines: What controls do we have in place to protect our critical information (financially sensitive data, IP, and client information) against all forms of cyberattack? How do we measure the effectiveness of these controls? Does the board understand the organization's dependence on information? Can the organization continue to operate if critical information is unavailable? What are the consequences of a security incident in terms of lost revenues, lost customers, and investor confidence? What are the consequences if the infrastructure becomes inoperable? Does the organization have a comprehensive crisis communication plan in place that is actionable at short notice? Does the organization have insurance that covers cybersecurity and IT risk? What is the potential liability if sensitive information is stolen and/or misused? |

| Have we identified our key information assets, and where they exist within our enterprise or partner IT systems? Do we know how vulnerable the identified assets are to attack? How regularly do we perform a risk assessment of cyberthreats against key systems identified? Do secure offsite backups of key data exist? Do we have a security strategy in place for social media, mobile devices, cloud computing, and employee use of personal devices (BYOD)? Do we have formal information security policies and awareness programs in place to ensure they are understood by the entire workforce? How do we monitor the effectiveness of these programs? Do we regularly brief or train employees at all levels in our security approaches? How do we report on security incidents? Do we have a rapid escalation and response plan in place? Who is responsible? Does information security appear as a board agenda item, and is there a schedule for reporting the status of the information security program to the board? Does the organization have a security strategy? If so, is it closely aligned with the overall business strategy? Does the chairman and appropriate board committee (IT governance, audit, and/or risk) clearly understand their role in setting the information security direction and policy with management? Are there management-level personnel specifically charged with managing information security in the organization? | |

|

Does your board have the capability to effectively lead and govern IT opportunity and risk? Does your organization (all levels) have a strategy-matching mix of competencies relevant to the digital future of your organization? Is strategy-related competency profiling conducted when new directors or key executives are recruited? Does your board have a capability development plan in place? Does the CEO have strong digital competency so that the right quality and level of information and technology information makes it into board papers, presentations, and management recommendations? How do you know? |

|

Does your board: Retain oversight of all phases of key technology project lifecycles from inception to measuring post-implementation value? Ensure that operational IT governance and IT control frameworks (e.g., CoBIT5, ITIL, TOGAF) are an integral part of planning, performance monitoring, and reporting (including board reporting)? |

|

The aim of a business continuity plan is to maintain system integrity and service quality. It should help retain competitive advantage and market share in spite of a crisis or extreme conditions. Imagine you are an airline or hospital and your core IT systems fail for whatever reason. Within seconds any or all of these seven areas of risk can come into play with high-cost, even disastrous consequences. Does your business continuity plan and disaster recovery plan cover all seven areas of risk? What information and/or technology assets are highest risk in a crisis? What are the most important assets that need to be secured first? Which assets need to be duplicated in case of an emergency? Which IT assets and resources are absolutely critical for business to continue with minimal disruption to customers and the business? Where and how can data be stored to ensure its safety at all times? How will clients, customers, employees, and stakeholders be informed if IT-based communications are down or compromised? How long can the organization be offline without incurring substantial or unsustainable losses? Who can perform the tasks necessary to carry on operations if a majority of the employees are unable to work? Does the organization have enough skilled employees to operate manual processes to minimize risk during catastrophic systems failure? |

|

Crisis communications are critical and should be an integral part of your plan: How do we minimize financial and market impacts of a crisis? What is our overall reputation containment and image protection plan? Under what circumstances is this enacted? How do we make sure we control the information flow resulting from a catastrophe, especially on social media? Who is our IT risk spokesperson (e.g., chair or CEO)? Does he or she have the digital literacy and ETG capability to speak in an information or technology-related crisis? |

Lack of capability can lead to: failure to identify risks and opportunities from digital disruption; the inability to obtain or measure a return from IT investments; failure of IT initiatives to bring the innovation and benefits they promised; technology that is inadequate or even obsolete; inability to leverage available new technologies; deadlines that are not met; and budgets that are inadequate or overrun (Deloitte, 2015; ITGI, 2011). So, let's not beat around the bush: ETG capability or the lack of it can contribute to either strengthening or weakening your organization's future position.

All too often, however, the reality of information and technology governance capability and enterprise risk exposure is attributable to poor board and executive IT knowledge, skills, and experience. Each of the seven areas of ETG risk outlined in Table 19.3 can also be opportunities to plan and prepare. This is why there is a critical need to assess development needs across the board and up-skill to make sure the necessary governance mechanisms—organizational structures, systems, policies, and reporting processes—are in place and barriers to board effectiveness are identified and removed.

Three Barriers to Effective Board-Level ETG

Risk is increased if any of the following barriers to your effectiveness as a board are present: (1) board composition/membership fails to include ETG competency; (2) board culture hinders information and technology opportunities or exacerbates risk; and (3) organization structure prevents or hinders opportunities for key IT people to engage with and educate the board. Table 19.4 provides a summary and suggests some practical solutions.

As Table 19.4 illustrates, most barriers relate to board members' individual and collective beliefs and attitudes to their role in ETG, and are underpinned by a lack of knowledge, skill, and experience in the area, as well as the lack of a sense of urgency. Barriers can be found in the priority the board puts on IT-related matters, including whether or not the topic makes it onto the board meeting agenda. Combating unconscious biases is hard, because they don't feel wrong; it's the way we've always done things. But it's necessary to uncover biases during rapid change so that a board culture is created which remains relevant in a digital era. This is because biases within the board culture can mean adherence to old ways of doing things that may no longer serve the board well.

Rapid Risk Response Is an Emerging Form of Agile Governance

Because any of the seven areas of IT risk can strike with lightning speed, traditional corporate governance approaches may need to be checked for responsiveness. The predominant board practice for overseeing risk is through board papers, board committees, and monthly meetings. This “governance by exception” approach may simply be too slow when it comes to ETG (Valentine, 2016). The solution is quite simple. The board must make sure that a more flexible set of responsibilities and processes are put in place and operate to bridge any rapid response barriers between the board and management. These must operate in parallel with current board reporting.

Table 19.4 Barriers, Symptoms and Suggested Solutions

| Barrier | Symptom | Solution |

| Not clear about what enterprise technology governance is | Many definitions of IT governance and enterprise technology governance do not separate IT management from IT governance. This potentially gives tardy directors a false sense that “IT Governance” is not the business of boards. This also can mean getting an “IT person” on the board without knowing the relevance of their skillset to the business and whether their skills will enhance board ETG capability. |

The ETG definition and the competency set provided in this chapter focus on the role and responsibilities of boards in a digital world. Helping established boards build on existing corporate governance capability and providing professional development so that they can begin to apply this knowledge to enterprise information and technology governance is an important first step. It is particularly important to build awareness of the changed roles of directors in leading, directing, and governing innovation and value creation, strategy, risk, performance, and compliance in this area. |

| Board beliefs and attitudes about technology | Beliefs about IT being a cost to manage rather than a strategic asset. When this is the case, technology matters seldom make it into board papers or discussions, despite evidence of increasing IT-driven change in their industry or competitive environment. |

Review company strategy and ask the hard questions about whether the current board membership has the knowledge, skills, and experience to ensure all seven areas of information and technology-related risk are covered. Use the competency set to analyze this, and to make sure that any gaps are prioritized and internal and external solutions found. Bring in talent and up-skill the whole board and executive if necessary, as technology now pervades every area of organizations. |

| Structural | The emphasis, positioning, orientation to information use, and influence of the chief information officer (CIO) or chief technology officer (CTO) can be signs. If the CIO or CTO does not have any role at the executive or board level or access to regular board briefings, there is potential for increased risk. IT operational management and corporate governance structures are likely to be disconnected. This means that IT is still treated like a separate part of the organization rather than a core, strategic capability that is measured and monitored along with finance and legal. |

Thoroughly examine the technology competency of the CEO, as he or she may be a filter to the board papers and technology strategy, risk, and investment effectiveness. Instigate quarterly briefings from the CIO or CTO. If he or she does not understand the business sufficiently, provide training. Establish an IT governance board committee and monitor its effectiveness. Ensure that technology investment is integral to the business plan, and investment prioritized to reduce risk and provide expected returns. Check how technology is impacting all technical disciplines. For example, are legal or finance examining new technology-based funding or business models or business applications? |

Had such a rapid IT risk response system been in place at Target USA, for example, the risk of prosecution would likely have been reduced. Boards that understand their risk profiles and put in more effective mechanisms—responsive structures, processes, and emergency response communications, for example—are significantly better placed to govern appropriately. An additional approach can be to improve IT governance reporting to the market and investors.

IT governance research (Joshi, Bollen, & Hassink, 2013) advocates the importance of technology governance communications to external stakeholders of the firm. Such research predicts that firms can improve their liquidity and firm valuation through better information disclosure.

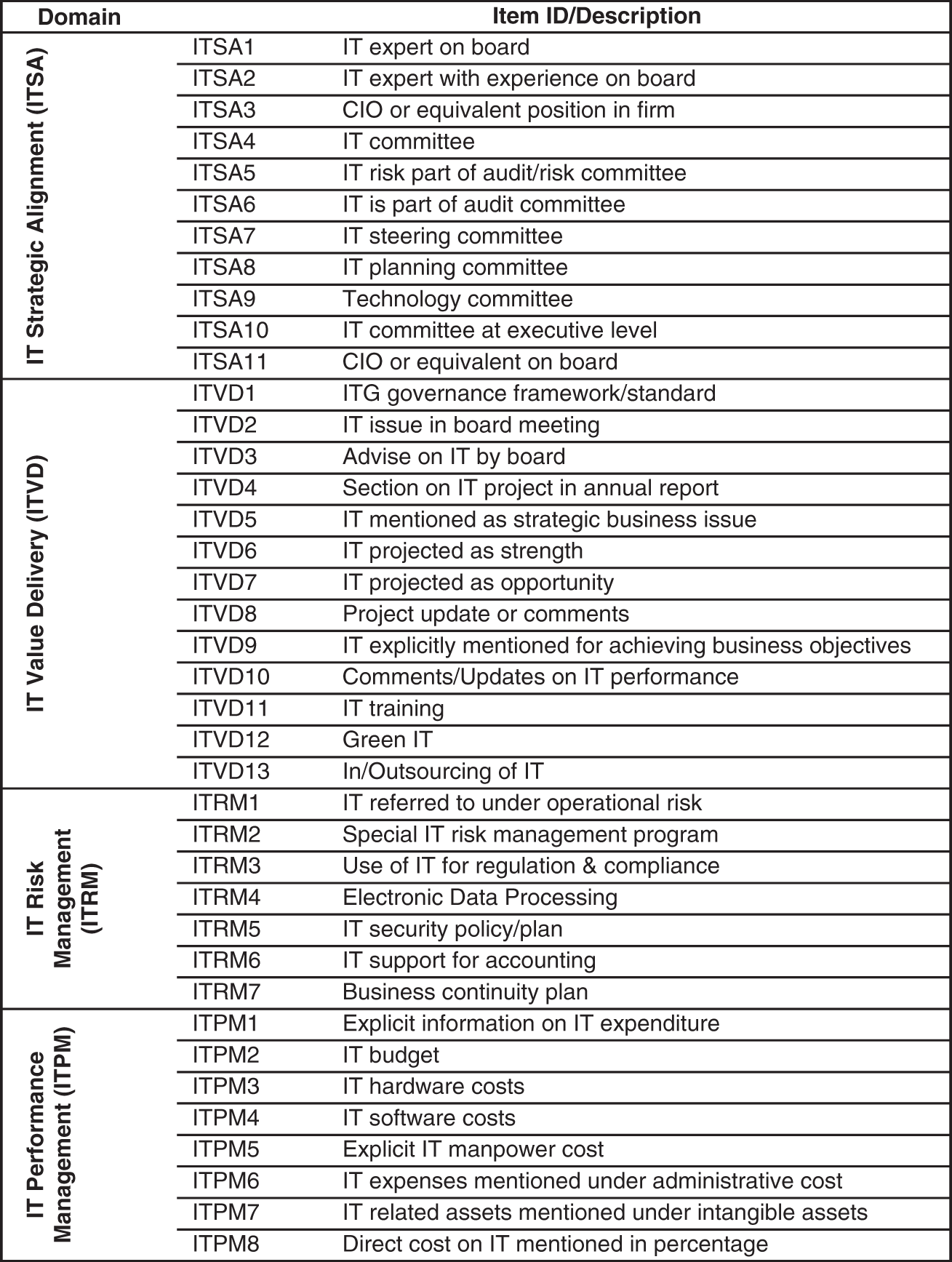

Firms can also enhance their market reputation and reduce litigation costs and the cost of capital because of IT governance disclosure. Building on the association between potential economic benefits and voluntary disclosure, Bünten, Joshi, De Haes, and Van Grembergen (2014), and Joshi, Bollen, Hassink, De Haes, and Van Grembergen (2018), demonstrate that a higher maturity of IT governance activities enables boards to create a better IT information environment and dissemination capability. As shown in Figure 19.3, to assess the level of technology governance disclosure, an IT Governance Disclosure Framework was developed by Joshi et al. (2013).

This framework consists of 39 disclosure items across four broad technology governance domains: IT strategic alignment (ITSA), IT value delivery (ITVD), IT risk management (ITRM), and IT performance management (ITPM). ITSA is concerned with the linkage of strategy, architecture, and processes on the IT and business side, whereas ITVD is related to providing quality IT products and services on time and within budget. ITRM investigates various IT risks such as operational, business continuity, and security risk while ITPM focuses on IT expenses and budgets. Each domain contains several items, indicating the existence of ITG-related features within that domain.

FIGURE 19.3 ITG Disclosure Framework

Source: Adapted from Joshi et al., 2013. Used with permission.

In one study, the 2012 annual reports of Belgian and Dutch listed companies were analyzed (Caluwe, 2014) against the Joshi ITG disclosure framework. The results show that the category which is reported most frequently is IT risk management. An explanation can be provided by the Belgian and Dutch corporate governance codes, which state that organizations need to report on systems for risk and internal control. Since IT keeps growing in importance in today's organizations, IT risk is often included. However, annual reports included very little on IT strategic alignment or how the board is engaged and their capability to oversee the other matters highlighted in the framework.

In the second of the two 2014 U.S. Investor Derivative Complaints of breach of fiduciary care, the Wyndham Worldwide Corporation suit was eventually dismissed after the court heard evidence of security strategies the organization had put in place. The company had taken significant steps to act on security feedback received from an earlier cyberattack.

Similarly, among many considerations in the Target USA case were: a lack of IT governance disclosure; disconnected ETG and operational IT governance and security initiatives, including no rapid risk response systems or processes; the absence of timely stakeholder communications; and a lack of ETG accountability and competency within the board and senior executives.

Board ETG Accountabilities and New Competencies

There are three areas of board accountability that have been translated into industry-validated enterprise information and technology governance competencies (Valentine, 2016). The first accountability and competency area is directing and governing technology-enabled strategy. The second is directing and governing technology investment and risk. The third is directing and governing technology-enabled innovation and value creation. Table 19.5 provides more detail of each competency, including a short definition and examples of the types of knowledge, skills, and experience directors need to build. This competency set was developed and validated with input from 419 experienced board chairmen, directors, senior executives, and consultants from 25 different industries and from a wide range of organization types and sizes from public, private, and not-for-profit organizations (Valentine, 2016).

A technical competency set of this type is part of the overall, wider picture of knowledge, skills, and experience required for success in the role of company director. These board- and executive-level ETG competencies can be used in a wide variety of ways.

Table 19.5 Board Enterprise Technology Governance Competency Descriptors

| Competency 1: Direct and govern technology-enabled strategy. | |

| Definition: Direct and govern technology-enabled strategy to maximize the advantages of technology and enhance performance at all levels of the organization. | |

| Descriptor C1-1 | Knowledgeable about current and emerging digital technologies and their potential to add organizational, customer, and stakeholder value. |

| Descriptor C1-2 | Skilled in business, environmental, and competitive analysis, including how industry sector and similar organizations are using new and emerging technologies and information. |

| Descriptor C1-3 | Skilled in overseeing the inclusion of current and future technologies into the organization's strategy, business plan development, organizational performance measures, and management Key Performance Indicators. |

| Descriptor C1-4 | Knowledgeable about the digitization of business processes that underpin peak performance and their relationship to overall corporate governance. |

| Descriptor C1- 5 | Knowledgeable about and skilled in evaluating the level of information and technology dependency the organization has now and may need in the future. |

| Descriptor C1-6 | Experienced in selecting, implementing, and monitoring the effectiveness of enterprise information and technology governance mechanisms (systems and processes). |

| Descriptor C1-7 | Able to oversee technology acquisition, implementation, maintenance, and disposal to meet the board's fiduciary, regulatory, compliance, ethical, contractual, and legal obligations (based on ISO/IEC, 2008). |

| Descriptor C1-8 | Knows what to measure and monitor and how to interpret business technology performance data against plans and policies to derive expected benefits and ensure strategic intent is achieved. |

| Competency 2: Direct and govern business technology investment and risk. | |

| Definition: Understands and uses information and data to evaluate, direct, monitor, and analyze information provided by management, supply partners, and advisors. Can ask probing questions and critically analyze management and external advisor responses. Can contribute to discussion to ensure that decisions about technology-related performance and risk oversight meet governance performance and conformance requirements. | |

| Descriptor C2- 1 | Understands how prioritized technology infrastructure investments help achieve enterprise business goals and reduce risk. |

| Descriptor C2-2 | Able to evaluate and mitigate infrastructure, information, privacy, data security, and reputational risk to ensure the continued operation of the business. |

| Descriptor C2-3 | Knows what areas of IT risk to measure, monitor, and report on, and how processes and policies support the board in meeting its fiduciary responsibilities in a timely manner. |

| Descriptor C2-4 | Demonstrates an understanding of technologies for identifying, tracking, mining, and exploiting the data and information relevant to the organization's needs. |

| Descriptor C2- 5 | Knowledgeable about the unique issues associated with digital technology investment and digital change capability to better focus and prioritize digital transformation initiatives. |

| Competency 3: Direct and govern technology-enabled innovation and value creation. | |

| Definition: Understands and can provide oversight of technology-enabled product and service development, business process efficiency, and stakeholder engagement. | |

| Descriptor C3-1 | Provides strategic leadership of an organizational culture that champions digital business technologies and uses data and information for decision-making and change leadership. |

| Descriptor C3-2 | Demonstrates knowledge of the implications, costs, and benefits of digital technologies such as business applications, mobile, and social technologies, the cloud and outsourced services, and the Internet-of-Things. |

| Descriptor C3-3 | Understands how to derive business value from technology investments, balancing risk and opportunity. |

| Descriptor C3-4 | Experienced in board-level governance oversight of large-scale IT projects to ensure promised outcomes are achieved. |

| Descriptor C3-5 | Knowledgeable about value creation through digital product, system, or service development. Can provide guidance to management in considering their value-creating uses for strategic advantage. |

| Descriptor C3-6 | Oversees technology asset lifecycles to derive expected returns. |

© This competency set, and all preceding and future derivatives, are copyright to Dr. Elizabeth L. H. Valentine 2013–2020 all rights reserved. Used with permission.

For example, a board could use the set to evaluate current board capability. Relevant questions from each of the three competencies could be included in the next board evaluation. Competency sets can also be used to identify director professional development needs, to evaluate board membership or structure, and to recruit or develop a succession plan for new members (Valentine, 2016).

Five Practical Steps to Start Transforming Your Board

By now it should be clear that continuing to ignore or delegate technology matters to management or consultants without strong board information technology governance capability can have serious consequences. Taking appropriate steps toward capable digital leadership and transformation can lead to increased performance, profits, or market capitalization no matter what size or type of organization or what industry sector. Here are some practical things a board can do.

Take the First Steps Toward Digital Transformation

Start the digital transformation process by hiring a skilled consultant to conduct a digital maturity audit. This will help your organization understand the focus and effectiveness of previous investments, and your organization's IT change capability.

Conduct an audit of current board ETG capability using the three competencies in Table 19.5. This will help identify whether you build capability through director professional development or recruit the necessary talent.

Evaluate the Digital Capability of Your Executive Team

Your chief executive's digital capability is critical. If he or she is not tech-savvy, critical information could be filtered out of board papers. Such filtering can impact investment priority, risk responses, or value-creation opportunities. Equally, because technology impacts all parts of operations, the currency of all executives' technology knowledge should be checked and professional development needs critically reviewed.

Review the current chief information officer (CIO) or chief technology officer (CTO) position in the organization structure. Are enterprise information and technology still considered an operational cost rather than a strategic asset by the board or executives? Does the CIO or CTO report directly to the chief executive? Is she or he capable of functioning across the business as a strategic business partner? Does the CIO/CTO engage with and brief the board on a regular basis?

Establish a Digital Vision for the Organization

Beyond alignment, technology and its governance have become integral to organizational strategy and its governance. A digital vision is not some pie-in-the-sky exercise. This is where your organizational strategy and digital future come together and stay together as one.

Use the above results to craft a flexible but an actionable, measurable vision achievement plan in place that forms the basis of your organization's board reporting.

Review Board Governance Structures and Processes

Check that board governance structures and processes will support the vision and plan and are appropriate to a digital business. Incorporate digital effectiveness measures into your performance reporting scorecard.

Review the structure and membership of board committees. Consider establishing a technology advisory or governance committee to focus on digital opportunities and risks.

Consider Your Board's Agility

Make sure rapid IT risk alerts and response systems and procedures are in place outside of normal board reporting. Know what actionable insights are required at each level of accountability, including the board; who is responsible; and what circumstances trigger the escalation of alerts. Make sure your board has an emergency communication plan that includes monitoring of social media networks. These types of actions ensure emergency responses will help meet technology-related duty-of-care responsibilities.

Conclusion

Until recently, firms with competent enterprise information and technology governance created medium-term competitive advantage within their industry sectors. They did this through using digital disruption; creating new business models; providing a superior customer experience; digitizing business operations; developing approaches to internal and external communications; the building of large and engaged online communities, and many other strategies with information and technology at the core. As capability grows, market leaders will use innovative digital strategies to both further develop and protect the value created and develop the capability to transform their organizations rapidly. Digital leaders increase the urgency for all boards to govern information and technology as strategic assets. Increasingly, the existence of competency around ETG within the boardroom will be needed not only to gain advantage, but to merely achieve parity with those who have recognized its essential nature as a new core competency. Those who remain in denial of the need to build IT capability at all levels risk joining the growing list of once-leading firms left behind in the digital “cloud of smoke” that characterizes the current and emerging operating environment.

About the Authors

Elizabeth Valentine is CIO of Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. She is also a teaching fellow and adjunct research fellow at the Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. She completed a Doctor of Information Technology at Queensland University of technology in 2016. Elizabeth brings significant consulting, chief executive, and company director experience as well as core skills in competency development to her work. A sought-after international speaker and executive coach, her consulting work specializes in digital strategy, digital director professional development, and the organization development/people aspects of digital transformation. Her doctoral thesis provided the first known multisector, international ETG competency set to help boards and senior executives build this much needed capability. Her work has been published in international peer-reviewed journals, books, and conference proceedings. Contact: [email protected].

Steven De Haes, PhD, is dean of Antwerp Management School and professor of Digital Strategy & Governance at Antwerp Management School and the University of Antwerp. He is actively engaged in teaching and applied research in the domains of Digital Strategies, IT Governance & Management, IT Strategy & Alignment, IT Value & Performance Management, IT Assurance & Audit and Information Risk & Security. His research has been published in international peer-reviewed journals and leading conferences. He is co-editor-in-chief of the International Journal on IT/Business Alignment and Governance (www.igi-global.com/ijitbag) and co-authored and/or edited several books, including Enterprise Governance of IT: Achieving Strategic Alignment and Value (Springer, first edition, 2009; second edition, 2015). He also acts as academic director of the IT Alignment and Governance (ITAG) Research Institute. He chairs research tracks on IT Governance and Alignment at the Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences and the European Conference on Information Systems. Contact: [email protected].

Anant Joshi is an assistant professor of Information Management at the Department of Accounting and Information Management at Maastricht University's School of Business and Economics. He is also a visiting scholar at the University of Antwerp and Antwerp Management School (Belgium). He holds a PhD degree in Management Information Systems from Maastricht University, Netherlands. His research interests include Corporate Governance of IT, Business Value of IT, and Corporate Governance. Anant coordinates and teaches a range of courses in the area of management information systems. Anant is actively involved in research at the Expertise Center Digital Business & IT at the Antwerp Management School, Belgium. Contact: [email protected].

Notes

- 1. https://digit.hbs.org/submission/walmart-blurring-the-lines-between-digital-and-physical/.

- 2. We separate information and technology rather than perpetuating old definitions of IT. This is because governing information and its security has become as important as governing essential decisions about the types of technology that will support and enable digital transformation.

- 3. This case study was originally published in (De Haes, Caluwe, Joshi, Huygh, & Jansen, 2017).

- 4. The study involved interviews with executives at 450 large companies and the survey was completed by 1,559 people in 106 countries (Fitzgerald et al., 2014).

- 5. UBER is a US-based company that started in 2009. It now has operations in countries around the world. UBER is a smartphone application for ridesharing that pre-calculates the fare, estimates a time of arrival, as well as offers the option to split the cost with additional riders, and charges a credit or debit card when the ride is complete. UBER has significantly disrupted the profits of the taxi and limousine industries. Uber's 2018 market capitalization was estimated at US$48bn.

- 6. Airbnb was founded in 2008 in San Francisco, California. It is a trusted community marketplace for people to list, discover, and book unique accommodation of all types, around the world online or from a mobile phone or tablet. Airbnb is an easy way for people to monetize their extra space and showcase it to an audience of millions. More recently AirBnB has entered the corporate traveler market. Airbnb's market value in 2018 was estimated at US$38bn, second only to the Hilton Chain.

- 7. https://www.businessinsurance.com/article/00010101/NEWS06/160719794/Target-case-a-cyber-warning-to-corporate-directors.

References

- Bayles, M. D. (1989). Professional Ethics (Wadsworth: Belmont, CA).

- Bünten, S., Joshi, A., De Haes, S., & Van Grembergen, W. (2014). Understanding the Association between IT Governance Maturity and IT Governance Disclosure. International Journal on IT/Business Alignment and Governance, 1.

- Butler, R., & Butler, M. J. (2010). Beyond King III: Assigning accountability for IT governance in South African enterprises. South African Journal of Business Management, 41(3), 33–45.

- Caluwe, L. (2014). IT Governance Transparency. (Masterthesis Project submitted for achieving the degree of Business Engineer in Information Systems Management), University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium.

- Carter, C. B., & Lorsch, J. W. (2004). Back to the Drawing Board: Designing Corporate Boards for a Complex World. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- De Haes, S., Caluwe, l., Joshi, A., Huygh, T., & Jansen, S. (2017). How boards engage in digital strategy and oversight: The case of Agfa-Gevaert, 12, https://repository.uantwerpen.be/docman/irua/a3432b/146015.pdf.

- De Haes, S., & Van Grembergen, W. (2015). Enterprise governance of information technology. Achieving Alignment and Value, Featuring COBIT, 5.

- De Haes, S., & Van Grembergen, W. (2015). Enterprise Governance of IT: Achieving Alignment and Value, 2nd ed. (Springer).

- Deloitte. (2015). Through the eyes of the board: Key governance issues for 2015. Retrieved from UK, https://www2.deloitte.com/bd/en/pages/risk/articles/directors-alert-2015.html

- Fitzgerald, M., Kruschwitz, N., Bonnet, D., & Welch, M. (2014). Embracing digital technology: A new strategic imperative. MIT Sloan Management Review, 55(2), 1–12.

- ISO/IEC. (2008). ISO/IEC 38500:2008, Corporate governance of information technology. In Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization.

- ITGI. (2006). Information Security Governance: Guidance for Board of Directors and Executive Management. Retrieved from Rolling Meadows, IL, www.itgi.org.

- ITGI. (2011). Global status report on the governance of enterprise IT (GEIT)–2011. Retrieved from Rolling Meadows, IL, http://www.isaca.org/Knowledge-Center/Research/ResearchDeliverables/Pages/Global-Status-Report-on-the-Governance-of-Enterprise-IT-GEIT-2011.aspx

- Joshi, A., Bollen, L., & Hassink, H. (2013). An Empirical Assessment of IT Governance Transparency: Evidence from Commercial Banking. Information Systems Management, 30(2), 116–136.

- Joshi, A., Bollen, L., Hassink, H., De Haes, S., & Van Grembergen, W. (2018). Explaining IT governance disclosure through the constructs of IT governance maturity and IT strategic role. Information & Management, 55(3), 368–380, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2017.09.003.

- Keen, P., & Williams, R. (2013). Value architectures for digital business: Beyond the business model. MIS Quarterly, 37(2), 643–647.

- Leblanc, R., & Gillies, J. (2005). Inside the Boardroom. Ontario: John Wiley & Sons.

- Luna, A. J. H. de O., Costa, C. P., Moura, H. P. de, Novaes, M. A., Nascimento, C. A. D. C. do & De Moura, H. P. (2010). Agile Governance in Information and Communication Technologies: Shifting Paradigms. JISTEM Journal of Information Systems and Technology Management, 7(2), 311–334. doi:10.4301/S1807-17752010000200004

- McAfee, A., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2008). Investing in the IT that makes a competitive difference. Harvard Business Review, 86(7/8), 98–107.

- Norfolk, D. (2011). IT Governance: Managing Information Technology for Business. Retrieved from http://QUT.eblib.com.au/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=799845.

- Parent, M., & Reich, B. H. (2009). Governing Information Technology Risk. California Management Review, 51(3), 134ff.

- Rathnayaka, A., Potdar, V., & Ou, M. (2012). Prosumer management in socio-technical smart grid. Paper presented at the CUBE '12 - CUBE International Information Technology Conference.

- Trautman, L. J., & Altenbaumer-Price, K. (2011). The board's responsibility for information technology governance. John Marshall Journal of Computer & Information Law, 29, 313.

- Turel, O., & Bart, C. (2014). Board-level IT governance and organizational performance. European Journal of Information Systems, 23(2), 223–239.

- United States District Court, Kulla vs. Target Corporation, 1–35 (2014a).

- United States District Court, Pakon vs. Warton Worldwide Corporation, 1–83 (2014b).

- Valentine, E. (2016). Enterprise technology governance: New information and technology core competencies for boards of directors. (Doctor of Information Technology Monograph), Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia.

- Valentine, E., & Stewart, G. (2013). Director competencies for effective enterprise technology governance. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 24th Australasian Conference on Information Systems (ACIS 2013).

- Westerman, G., Bonnet, D., & McAfee, A. (2015), Leading digital: Turning technology into business transformation, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com. (2015).

- Westerman, G., Tannou, M., Bonnet, D., Ferraris, P., & McAfee, A. (2012). The digital advantage: How digital leaders outperform their peers in every industry. Retrieved from Capgemini Consulting, https://www.capgemini.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/The_Digital_Advantage__How_Digital_Leaders_Outperform_their_Peers_in_Every_Industry.pdf