58

Boards of Directors of Chinese Companies

David H. Zhu

Associate Professor of Management and Entrepreneurship, W. P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State University

Wei'An Li

Professor of Management and Governance, China Academy of Corporate Governance/Business School, Nankai University

Yaowei Zhang

Associate Professor of Management and Governance, China Academy of Corporate Governance/Business School, Nankai University

Introduction

In July of 2018, Fortune published its latest list of the world's 500 largest companies by revenue, known as the Global 500. This time, China has 120 companies on the list, just behind the United States (126 companies) but way ahead of Japan (52 companies). Among the 120 Chinese companies, about 80 percent are state-owned corporations, but the 20 percent of privately owned (i.e., not owned by the state), publicly traded firms include some familiar names, such as Alibaba and Haier. Although Chinese companies are gaining increasing attention from investors, customers, businesses, and politicians worldwide, only limited research has systematically examined the corporate governance system in China (Useem, Singh, Liang, and Cappelli, 2017, is a notable exception), with particularly scarce coverage of the governance of state-owned firms. Our goal in this chapter is to partially address this issue.

Establishment and Development of the Chinese Board of Directors System

The Chinese corporate governance system has changed substantially over time, especially following the economic reform policies initiated by Xiaoping Deng in 1978. Because the state almost entirely controlled the economy when these reforms started, the country sought to learn from prevailing corporate governance practices in other countries. The guiding principles for Chinese corporate governance thus incorporated insights from influential theories such as agency theory and stakeholder theory and reflected a unique integration and development of governance practices in other parts of the world. We thus start by briefly discussing three relevant theories about corporate governance and then discuss how the Chinese corporate governance system incorporated these theories in different ways during different periods of its development.

Key to Board Governance: Inclusiveness and Independence

In the early stages of the development of the modern enterprise system, accountability to shareholders was widely believed to be the key responsibility of a company (Berle and Means, 1967). In particular, agency theory suggests that shareholders are residual claimants who get paid only after a company fulfills contractual obligations to all other stakeholders. Therefore, under the assumption that other stakeholders can be fairly protected by their contracts, the enterprise is held primarily responsible to shareholders (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Fama and Jensen, 1983). However, as enterprises developed, operating based only on the interests of shareholders was repeatedly challenged, in part due to the failures of using contracts alone to protect other stakeholders' interests. Since the 1960s, people began to pay more and more attention to the social responsibility of companies, and the theory of stakeholder governance came into being (Freeman, 1984; Donaldson and Preston, 1995). According to this stakeholder logic, companies needed to respond to the increasingly diverse demands of both internal and external stakeholders, including but not limited to shareholders, and they gradually developed a set of internal and external governance mechanisms, with the board as the core. In recent years, more and more people have started to believe that the essence of the modern corporate governance system is to achieve the inclusion of multiple stakeholders through specific institutional arrangements. The company is the focal point of all stakeholders and is responsible for all stakeholders. Accordingly, many believe that representatives of various stakeholders should be included in the corporate governance structure, and stakeholders should be fully considered in operational decision-making.

As the scope of corporate responsibility evolves from early shareholder responsibilities to stakeholder responsibilities, the latest form of expression is green responsibility (Li, 2016a). While shareholder responsibility and stakeholder responsibility both emphasize the mutual dependences and mutual interests among different types of resource providers, the logic of green responsibility suggests that nature should also be considered as a key participant of the corporate governance system. According to Li (2016a), the modern enterprise system needs to transform from the unilateral consideration of human needs to the bilateral consideration of the environment as an equal subject in order to achieve inclusive and sustainable development. In other words, the activities of enterprises should be planned with a comprehensive consideration of natural resource constraints and environmental affordability. The essence of green responsibility lies in treating the company's stakeholders and nature equally, rationally balancing the relationship between human desire and environmental needs. Green responsibility is compatible with shareholder responsibility and stakeholder responsibility, and is the further expansion of the social responsibility concept.

The key to the realization of corporate responsibility objectives lies in the board of directors. As the daily operational decision-making body and legal representative of the company, the board of directors in China is widely expected to make independent and objective decisions and maximize the company's value while taking into account the interests of all stakeholders (Li, 2016b). The logic behind this is that the board of directors is accountable to all stakeholders and should make decisions in a way that is in the company's overall interest. On the one hand, the company's stakeholders are diversified, and all stakeholders have their own special interests. This requires the company's board of directors to take into account the interests of all parties in the decision-making process and promote inclusiveness. On the other hand, the board of directors must make decisions independently. Fair treatment of all stakeholders requires the board to maintain independence in the decision-making process, focusing on the company's overall interests. In practice, the board of directors generally seeks to achieve the above objectives by increasing the diversity of board members (i.e., including main stakeholder representatives, external directors, etc.) and promoting its independence.

Introduction of the Board of Directors System in China

The board system of Chinese companies is constantly improving along with the development of the country's modern enterprise system. When the market-oriented reforms were implemented in 1978, all companies in China were owned and managed by the state. Accordingly, a discussion of how the board of directors system in China has evolved must start with a discussion of Chinese state-owned firms.

Since 1978, Chinese state-owned firms have experienced several stages of development, from direct government management to the system of holding managers responsible and eventually to the establishment of modern corporate governance structures. The board of directors, which is an important part of the state-owned enterprise (SOE) management system, has also evolved, from having no board of directors to establishing a board of directors to continuously improving the board system. With the deepening of market-oriented reforms and the continuous improvement of governance laws such as the Company Law and the Guidelines for the Governance of Listed Companies, Chinese corporate governance is transforming from an administrative governance model under the planned economy to an economic governance model under the market economy. The focus of board governance has also shifted from compliance to effective operation.

In 1992, in order to meet the needs of reform in the new era, China clearly proposed establishing a socialist market system to enable the market to play a fundamental role in resource allocation under the state's macroeconomic regulation and control. Therefore, enterprises that are the microfoundation of the market economy had to truly become self-managed and self-sufficient market players. The market-oriented reforms and the establishment of the enterprise's position in the market required corresponding institutional guarantees.

In November 1993, “to further transform the operating mechanism of state-owned enterprises,” the Third Plenary Session of the 14th Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee requested the establishment of “a modern enterprise system that meets the requirements of the market economy. The system needs to have clear property rights, establish clear rights and responsibilities, separate the government from enterprises, and implement scientific management.” Since then, establishing the modern enterprise system has become the fundamental goal and direction of China's reform of state-owned firms.

In December 1993 the National People's Congress passed the Company Law of the People's Republic of China (hereinafter referred to as the Company Law), which clarifies companies' legal person status and organizational governance structure. According to the Company Law, a limited liability company shall establish a shareholder meeting, a board of directors, and a board of supervisors; an enterprise funded solely by the state shall not establish a shareholder meeting but shall establish a board of directors; a limited company shall establish a general meeting of shareholders, a board of directors, and a board of supervisors. The Company Law also specifies regulations of the board meeting, the powers of the board of directors, and the authority of the chairman.

After the promulgation of the Company Law, new companies were established in accordance with the law, and all existing limited companies established a board of directors according to the law. At the same time, the original state-owned large and medium-sized enterprises still operated in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Law on the Industrial Enterprises of the Whole People, but they gradually realized corporate restructuring with the deepening of economic reform.

In 1994, the State Council selected 100 state-owned large and medium-sized enterprises to carry out the pilot of the modern enterprise system. The provincial and municipal governments also selected 2,500 enterprises to conduct similar pilots in accordance with their own circumstances, and the board of directors system was officially introduced. China proposed that at the end of the twentieth century, most state-owned large and medium-sized enterprises should initially establish a modern enterprise system and become legal entities and participants in market competition, with “self-management, self-sufficiency, self-development, self-discipline.” In this process, the reform of most state-owned firms was intended to achieve clear and quantifiable property rights through various methods, providing managers and employees with strong incentives.

To expand the financing channels of state-owned firms and deepen the reform of the modern enterprise system, the Shanghai Stock Exchange was established in December 1990 and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange in May 1991. The capital market has generally developed by “crossing the river by feeling the stones,” continually improving the institutional system through experimentation. Once a company becomes publicly listed, it is supervised by securities companies, accounting firms, and so forth, and is regulated by the Shanghai or Shenzhen Stock Exchange (securities regulatory authorities). Publicly listed companies need to comply with mandatory information disclosure regulations and are expected to improve corporate governance practices over time. By the end of 2017, there were 3,485 listed companies in China's Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets, with a total market capitalization of 56.71 trillion yuan.

The development of the capital market and the improvement of the institutional system have promoted the continuous improvement of the governance of the board of directors of listed companies. In 2001, the China Securities Regulatory Commission issued the Guiding Opinions on Establishing an Independent Director System in Listed Companies. It stipulated that an independent director of a listed company is a director who has no other appointments with the company and has no relations with the company or its major shareholders that may hinder the director's ability to make independent and objective judgments. All listed Chinese companies were required to revise their company charters accordingly and appoint appropriate personnel to serve as independent directors, including at least one accounting professional (those with senior professional titles or qualification as certified public accountants). By June 30, 2002, the boards of directors of all listed companies were to include at least two independent directors; before June 30, 2003, boards of directors of listed companies were to include at least one-third independent directors. The Guiding Opinions also stipulated that the boards of directors of listed companies, the boards of supervisors, and shareholders who individually or jointly hold more than 1 percent of the issued shares may nominate candidates for independent directors, who will be elected by the general meeting of shareholders.

In 2002, the China Securities Regulatory Commission issued the Guidelines for the Governance of Listed Companies, which stipulated the procedures for selecting the board of directors, the obligations of directors, the composition and duties of the board of directors, the rules for directors' meetings, the independent director system, and the special committees of the board of directors. In 2005, the newly revised Company Law clarified further details about issues of protecting small and medium investors, shareholder responsibility, and information transparency in the capital market. It also promoted the continuous regulation and formalization of the board of directors system for listed companies.

Structure and Operation of the Board of Directors of Chinese Listed Companies

The quality of board governance has long been a major issue in corporate governance research. In China, the effectiveness of the board is significantly influenced by its composition and operational conditions. The board of directors of a Chinese company can be divided into executive directors and nonexecutive directors. An executive director participates in the company's internal operations and management, actively formulates and implements the company's strategies, and has in-depth knowledge about the company's internal and external conditions. Nonexecutive directors can be further divided into independent nonexecutive directors (commonly known as independent directors) and related nonexecutive directors (commonly known as nonexecutive directors). As required by the Company Law, an independent director has no other appointments with the company and has no relations with the company or its major shareholders that may hinder the director's ability to make independent and objective judgments. In contrast, related nonexecutive directors are typically large shareholders of the company or directors appointed by the controlling shareholders, actual controllers, or other shareholders of the listed company, but they do not have other managerial positions with the company.

The proportion of independent directors is relatively homogeneous across companies in China. Because the Guiding Opinions on Establishing an Independent Director System in Listed Companies issued by the China Securities Regulatory Commission stipulates that the number of independent directors in listed companies should account for at least one-third of the number of board members, that's the percentage most companies appointed. Research shows that the effectiveness of independent directors in China is limited, and the board's actual degree of independence is questionable. For example, independent directors often do not openly object or question management's decisions, rarely exercise their voting rights against management, and have been called “rubberstamps,” “vase directors,” and “guanxi directors” (Ye et al., 2011).

Nonexecutive directors have received more and more scholarly attention in recent years. According to the China Center for Economic Research (CCER) database, most boards of companies listed on China's Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share markets have nine directors, and nearly 80 percent of them have 7 to 11 directors. Overall, slightly more than one-third are independent directors, and executive directors and nonexecutive directors each account for about one-third of the board. China's listed companies have a relatively high degree of owner concentration, and most of them have large controlling shareholders and other shareholders with important influence. Because most of the nonexecutive directors are directly appointed by the controlling shareholder or a major shareholder with significant influence, they are more independent of management and are more capable than independent directors of expressing opinions on behalf of shareholders. In addition, nonexecutive directors often serve as top executives of other firms controlled by influential shareholders, and hence have a deep understanding of the operation of listed companies. Their knowledge and executive background reduce the degree of information asymmetry between them and company management, increasing their supervision ability over management (Lu and Hu, 2015).

The Company Law stipulates that board meetings should be held at least twice a year. Table 58.1 shows that the number of annual board meetings of companies listed on China's Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share markets increased in the early stage, and has remained at an average of nine per year in recent years. This indicates that the functioning of the board of directors has standardized over time.

In terms of the leadership structure of the board of directors, most Chinese listed companies have chosen to have a separate CEO and board chair, but the proportion of companies that adopted a CEO-chair duality (i.e., the CEO also serves as the board chair) has gradually increased in recent years. As shown in Table 58.2, the leadership structure of Chinese enterprises includes several variants: the CEO serves as the board chair, the CEO serves as the vice chair or a director, or the CEO is not a director of the board. Overall, from 1998 to 2017, more than half of the listed companies adopted a separated leadership structure in which the CEO does not serve as the board chair, and since 1999 more than half of companies have not even included the CEO as a member of the board. Specifically, from 1998 to 2002, the proportion of companies with CEO-chair duality decreased, but from 2002 to 2017, the proportion of companies with CEO-chair duality increased in all years (with the exception of a slight decline in 2014), reaching almost 29 percent in 2017. The proportion of boards where the vice chair or director served as the CEO stayed largely unchanged in the first 10 years of this period but started to decline in 2008, stabilizing at around 10 percent. The proportion of boards that excluded the CEO as a member increased from 45 percent in 1998 to 72 percent in 2006, and then decreased and fluctuated around 60 percent to 64 percent.

Table 58.1 Composition and Operation of the Board of Directors of Shanghai (SH) and Shenzhen (SZ) A-share Companies from 1998 to 2017

| Year | Number of board meetings per year | Board size | Number of independent directors | Percentage of independent directors | ||||

| SH | SZ | SH | SZ | SH | SZ | SH | SZ | |

| 1998 | 4.1 | 4.43 | 9.55 | 9.45 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.42% | 0.32% |

| 1999 | 4.81 | 4.91 | 9.63 | 9.35 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.62% | 0.64% |

| 2000 | 5.36 | 5.42 | 9.21 | 9 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 1.30% | 0.78% |

| 2001 | 6.14 | 6.49 | 9.13 | 8.96 | 0.61 | 0.55 | 6.68% | 6.14% |

| 2002 | 8.3 | 8.84 | 9.48 | 9.43 | 2.21 | 2.19 | 23.31% | 23.22% |

| 2003 | 7.18 | 7.73 | 9.75 | 9.53 | 3.2 | 3.04 | 32.82% | 31.90% |

| 2004 | 7.21 | 7.5 | 9.61 | 9.36 | 3.3 | 3.18 | 34.34% | 33.97% |

| 2005 | 7.33 | 7.51 | 9.67 | 9.21 | 3.35 | 3.19 | 34.64% | 34.64% |

| 2006 | 7.95 | 7.78 | 9.34 | 8.89 | 3.28 | 3.17 | 35.12% | 35.66% |

| 2007 | 9.18 | 8.9 | 9.33 | 8.97 | 3.32 | 3.21 | 35.58% | 35.79% |

| 2008 | 9.64 | 9.47 | 9.3 | 8.9 | 3.35 | 3.22 | 36.02% | 36.18% |

| 2009 | 8.72 | 8.26 | 9.28 | 8.64 | 3.38 | 3.17 | 36.42% | 36.69% |

| 2010 | 9.02 | 8.78 | 9.4 | 8.61 | 3.42 | 3.13 | 36.38% | 36.35% |

| 2011 | 9.45 | 9.34 | 9.26 | 8.54 | 3.39 | 3.16 | 36.61% | 37.00% |

| 2012 | 9.55 | 9.26 | 9.85 | 9.04 | 3.54 | 3.25 | 35.94% | 35.95% |

| 2013 | 8.99 | 8.69 | 10.15 | 8.35 | 3.79 | 3.08 | 37.34% | 36.89% |

| 2014 | 9.58 | 9.52 | 10.12 | 8.6 | 3.81 | 3.07 | 37.65% | 35.70% |

| 2015 | 9.54 | 9.93 | 10.32 | 9.26 | 3.9 | 3.56 | 37.79% | 38.44% |

| 2016 | 10.34 | 10.5 | 9.03 | 8.17 | 3.34 | 3.01 | 36.99% | 36.84% |

| 2017 | 9.97 | 10.22 | 9.2 | 8.22 | 3.43 | 3.03 | 37.28% | 36.86% |

Data source: CCER and CSMAR database.

Table 58.2 Board Leadership Structure of Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share Companies, 1998–2017

| Board leadership structure | Board committees | ||||||

| Year | CEO is chair | CEO is vice chair or director | CEO is not a director | Audit | Nomination | Strategy | Compensation and appraisal |

| 1998 | 23.15% | 14.18% | 45.09% | .1% | — | — | — |

| 1999 | 17.66% | 13.87% | 54.28% | .3% | — | .1% | — |

| 2000 | 12.26% | 14.81% | 60.57% | .9% | .4% | .8% | .5% |

| 2001 | 10.65% | 14.88% | 65.93% | 5.8% | 3.4% | 3.8% | 6.0% |

| 2002 | 9.92% | 14.76% | 65.80% | 27.9% | 22.7% | 25.3% | 30.9% |

| 2003 | 10.55% | 14.67% | 67.64% | 40.2% | 33.2% | 37.4% | 43.5% |

| 2004 | 11.24% | 15.24% | 69.60% | 46.8% | 38.8% | 42.8% | 49.1% |

| 2005 | 11.47% | 14.66% | 71.87% | 51.0% | 41.7% | 45.8% | 53.9% |

| 2006 | 12.48% | 13.76% | 72.13% | 54.8% | 44.8% | 48.9% | 58.3% |

| 2007 | 14.61% | 14.29% | 69.27% | 90.0% | 64.7% | 69.3% | 88.5% |

| 2008 | 15.92% | 13.61% | 68.91% | 99.0% | 78.8% | 81.2% | 98.0% |

| 2009 | 17.20% | 13.18% | 68.56% | 99.8% | 84.7% | 87.1% | 98.6% |

| 2010 | 21.37% | 11.62% | 65.78% | 99.8% | 71.9% | 72.5% | 99.0% |

| 2011 | 21.58% | 10.23% | 61.55% | 99.7% | 73.2% | 71.4% | 98.8% |

| 2012 | 21.86% | 9.92% | 62.96% | 89.1% | 75.1% | 71.9% | 93.8% |

| 2013 | 23.91% | 10.90% | 63.78% | 97.1% | 90.2% | 90.6% | 98.6% |

| 2014 | 23.17% | 10.39% | 62.90% | 79.2% | 74.2% | 74.9% | 79.8% |

| 2015 | 23.50% | 9.86% | 62.68% | 94.4% | 82.3% | 81.7% | 94.3% |

| 2016 | 25.20% | 9.53% | 62.37% | 99.0% | 88.0% | 87.4% | 96.6% |

| 2017 | 28.64% | 9.01% | 60.51% | 99.3% | 94.7% | 95.4% | 99.1% |

Data source: CCER and CSMAR database.

The Guidelines for the Governance of Listed Companies stipulates that boards of listed companies need to establish special committees on strategic management, auditing, nomination, compensation, and appraisal. By the end of 2017, more than 99 percent of boards of A-share listed companies had established audit, compensation, and appraisal committees, and more than 95 percent had established strategic management and nomination committees.

Chinese listed companies are also increasing the diversity of board members to better serve the interests of more stakeholders. For example, although there are no relevant regulations in China to regulate the proportion of female directors, society's attention to female directors has risen, and more and more women have been appointed to serve as directors of Chinese companies. According to the CCER database, as of March 2018, there were 75,444 directors of 3,499 A-share listed companies, 13,863 of whom were women, accounting for 18.38 percent of all directors; 178 boards were chaired by women, accounting for 5.09 percent of all chair positions.

Board Governance of State-Owned Enterprises

Transformation from an Administrative to an Economic Model of Governance

Under the planned economy, all Chinese enterprises were directly managed by the government, and administrative governance was the typical model. The three major connotations of this model are the administrative allocation of resources, the administrative process of setting business objectives, and the administrative process of appointing top executives. When China made the major strategic decision in 1978 to implement the economic reform and opening-up policy, the focus was enterprises, especially state-owned firms. In the early stages, the reform of state-owned firms focused mainly on the adjustment of government and corporate power. The government successively implemented measures such as expanding enterprise autonomy, profit sharing, decentralization, and contracting operations. These measures produced certain positive effects. However, because the deep-level institutional problems of state-owned firms had not been fundamentally solved, they were still largely subsidized by the government and had not become truly self-sufficient participants in market activities. Inefficiency and lack of vitality still plagued these firms.

While the logic of reforming state-owned firms is to transition from an administrative governance model under the planned economy to an economic governance model under the market economy, senior executives were both business managers and officials of the government during this transition. This dual identity led to a mismatch of incentives and constraints—top executives had both economic motives for maximizing corporate profits and administrative motives for pursuing political promotions. The administrative orientation of corporate governance was prominently reflected in the externalization of internal governance issues and internalization of external governance issues. That is, the decision-making functions that should be performed by internal governance bodies, such as decisions about executive compensation and equity incentives, were determined by external entities such as the government, while many external functions of governance, such as the functions of the enterprise to address social issues in the society, were carried out by internal entities such as the board or the top executive team.

One of the most important tasks in reforming state-owned firms is establishing a modern enterprise system. As a modern enterprise system, a company needs to rely on the economic mode of governance to meet the requirements of the market economy. It needs to focus on market-oriented allocation of resources and economic objectives, and to improve internal governance mechanisms under the premise that the government sets clear boundaries between administrative and market activities. We will first focus on the board governance of state-owned firms.

Different Types of State-Owned Firms in China

According to the regulations for registering a firm in China, state-owned firms can be classified into three broad categories. State-owned enterprises are registered according to the Regulations on the Administration of Enterprise Legal Person Registration of the People's Republic of China and the Law of the People's Republic of China on Industrial Enterprises Under Ownership by the Whole People (first issued in 1988). Until recently, these SOEs represented the majority of state-owned firms in China and were managed largely under the traditional administrative model of governance. These SOEs are also known as “enterprises funded solely by the state.” Following the passage of the Company Law, most state-owned firms transitioned to become corporations. When these corporations are funded solely by the state and supervised by special government entities, they are known as “corporations funded solely by the state.” Over time, various government entities, including corporations funded solely by the state, invested in other companies and became their controlling shareholders, and these companies are commonly known as state-controlled corporations. There are also companies that are partially owned by the state, but the controlling shareholder is not the state. These companies are commonly called “state-participating corporations.” Corporations funded solely by the state, state-controlled corporations, and state-participating corporations are all results of the pilot work of China's modern enterprise system.

Despite the great achievements of this pilot work, there are still some problems. For example, most state-owned firms that implemented the pilot of the modern enterprise system in the early stages of the reform were lower-level subsidiaries. They gradually built a standardized board governance system in accordance with the requirements of the Company Law, especially those companies already listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges. However, their parent companies were often not listed and were operating in accordance with rules preceding the Company Law. A modern corporate governance system has not yet been established among many parent companies of state-owned firms, and the parent companies have lagged behind the governance reform process of the subsidiaries.

Because state-owned parent companies have unstandardized governance practices, there are also many governance problems at listed companies. For example, the decision-making power and executive power of enterprises are highly centralized, and the board of directors has not played its due role. To solve the fundamental problem of state-owned firms, the Chinese government must establish a truly modern enterprise system in line with the rules of the market economy at the parent company level, improve the corporate governance structure, and achieve the major goals of reform—namely, clear property rights, clear powers and responsibilities, separation of government and enterprise, and scientific management. Among the key issues, the role of funders and the improvement of the state-owned firms' board governance are the core. The reform of board governance has also focused mainly on the relationship between the funders of state-owned firms and the board of directors.

Board Governance Reform of Corporations Funded Solely by the State

On March 10, 2003, the First Session of the Tenth National People's Congress voted to establish a State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) directly under the State Council to perform the duties of the investor on behalf of the state. According to the division of state-owned assets management authorities, state-owned firms are divided into central enterprises (state-owned enterprises supervised and managed by the central government) and local enterprises (state-owned enterprises supervised and managed by local governments at all levels). Correspondingly, local state-owned assets supervision and management committees are also established in various places. The SASAC of the State Council exercises the power of the investor in central enterprises, and the local SASACs exercise the power of the investor in the corresponding local enterprises.

Since the establishment of the SASAC of the State Council, the enterprises it directly supervises are mainly state-owned firms with only one shareholder (i.e., the government of the people). Most of these central enterprises were registered in accordance with the Company Law and established boards of directors. In the process of transforming into modern corporations, these enterprises funded solely by the state mostly adopted the shareholding system and determined the seats on the board of directors according to the weight of the stock ratio—there are often different entities of the government that own a given firm on behalf of the state, often involving the SASAC and/or Central Huijin Investment Ltd., a state-owned investment company that exercises shareholder rights on behalf of the Chinese State Council. Through the improvement of various management systems, these companies sought to better define the powers and responsibilities among government shareholders, the board of directors, the board of supervisors, and the management, and to ensure operational efficiency.

With this background, we can now focus on discussing the board governance of corporations funded solely by the state because these companies represent a typical state-owned company. A corporation funded solely by the state officially refers to a limited liability company that is authorized by the State Council or the local people's government to appoint the SASAC at the same level to perform the duties of the investor. The Company Law (revised in 2005) specifically clarified the governance of corporations funded solely by the state, stipulating that the company charter of such a corporation shall be formulated directly by state-owned assets supervision and administration institutions, or by the board of directors for approval by state-owned assets supervision and administration institutions. Corporations funded solely by the state do not have a shareholder meeting, and state-owned assets supervision and administration institutions exercise the powers of the shareholders' meeting. The state-owned assets supervision and administration institution may authorize the company's board of directors to exercise part of the powers of the shareholders' meeting and determine the company's major issues. However, merger, division, dissolution, increase or decrease of registered capital, and issuance of corporate bonds must be decided by the state-owned assets supervision and administration institution. When an important corporation funded solely by the state needs to be merged, divided, dissolved, or bankrupted, the decision shall be reviewed by the state-owned assets supervision and administration institution and then reported to the people's government at the same level for final approval.

To promote scientific decision-making and market-oriented corporate governance, the SASAC decided to conduct a pilot project for the construction of the boards of directors in the central enterprises. The SASAC has conducted considerable institutional exploration, including the pilot construction of boards of directors with a majority of external directors and the establishment of standardized special committees. Specifically, in June 2004, the SASAC of the People's Republic of China promulgated the Notice on the Establishment and Improvement of the Pilot Work of the Board of Directors of State-Owned Central Enterprises and subsequently carried out pilot work on the boards of directors of central enterprises. The main practice was to introduce external directors, separate decision-making rights from decision-execution rights, ensure independent judgments of the board, and realize truly collective decision-making to better protect the interests of the shareholders. The improvement of the modern enterprise system of central enterprises has also effectively promoted the governance of listed companies and the development of standardized capital markets. As of May 2018, the central enterprises controlled 290 listed companies in China, with a market capitalization of 11.1 trillion yuan, accounting for 20.66 percent of the total market value of the Chinese A-share market.

Major Initiatives for the Boards of Directors of Corporations Funded Solely by the State

In recent years, the SASAC has formulated various management systems and rules for the construction of boards of directors according to the Company Law. The focus of the reform was to clarify the responsibilities of shareholders (i.e., the state-owned assets supervision and administration institutions), and to give the board more independence and greater power. The state-owned assets supervision and administration institution may authorize the board of directors of the pilot company to exercise part of the functions and powers of the shareholders' meeting and decide on major matters of the company (such as development strategy and investment plan, etc.), but the merger, division, dissolution, increase or decrease of registered capital, and issuance of corporate bonds of the company must be decided by the state-owned assets supervision and administration institution. A remarkable progress in the reform was that the board of directors was gradually given power to select and evaluate the managers, who were traditionally directly appointed and assessed by the state-owned assets supervision and administration agency.

The pilot enterprises also established the board of directors in accordance with the Company Law, created special committees of the board of directors, appointed the secretary of the board of directors, and established the board of directors' office as the daily working organization of the board of directors. The board of directors of the pilot enterprises generally set up special committees such as the Nomination Committee, the Remuneration and Appraisal Committee, the Strategy Committee, and the Audit Committee. Pilot companies have certain degrees of freedom in the establishment of special committees. For example, China Coal Science and Technology Corporation established a safety and emergency management committee based on industry characteristics. In accordance with the rules of procedure of the board of directors, special committees conduct advanced analysis and research on major decisions before the board of directors. After sufficient discussions, special committee members form specific opinions and suggestions, and then submit them to the board of directors for deliberation and decision-making.

The SASAC selects and hires qualified personnel from outside the company to serve as external directors of these enterprises. In general, the external directors of the central enterprises are mainly retired senior executives of central enterprises, acting senior executives of other central enterprises, senior executives of other Chinese or foreign enterprises, scholars at academic research institutions, and the chairman of the former central enterprise supervisory board. The number of directors in the pilot enterprises is generally between 6 and 13, and the external directors are generally the majority. Some companies even explored the appointment of an external director as the board chair.

All pilot central enterprises are further required by SASAC to have at least one employee director. Employee directors are democratically elected by the employee representative assembly or the labor union general meeting, but their appointments need to be approved by the SASAC. They represent the employees while participating in the exercise of the powers of the board; they enjoy the same rights as other directors and assume corresponding obligations. Most employee directors are chairmen of the labor union, heads of a main department of the enterprise, or leaders of subsidiaries (some are more than one of these).

The boards of directors of corporations funded solely by the state serve three functions: first, through the construction of the board of directors system, the SASAC will change its role from the manager of the state-owned enterprises to their investors, and the central enterprises should more effectively assume operational independence from the state. Second, the board of directors system more effectively separates the decision-making function from the decision-execution function of the central enterprises. Third, the board of directors system enabled the implementation of the professional manager system and solved the problem of unclear boundaries and duties between the board of directors and the management. As of the end of August 2018, 94 of the 96 central enterprises directly supervised by the SASAC had established boards of directors, 83 of which included more than 50 percent external directors. At the same time, 90 percent of all state-owned enterprises regulated by local SASACs had established boards of directors.

Governance of the Board of Directors of Private Enterprises

Dual Identity of Family Members in Private Enterprises

Private enterprises in China are mostly family businesses founded by entrepreneurs. Because many private enterprises are listed as public firms, the term “private” is used with a special meaning, mainly distinguishing these firms from state-owned firms. In most private enterprises, entrepreneurial families are both owners and managers of the business. The operation, decision-making, executive, and supervisory powers of these enterprises are typically all controlled by members of the entrepreneurial family. In most family-owned private enterprises, a member of the family serves as both the chairman of the board and the CEO. Shareholders' meetings and board meetings are both under the substantial influence of the owning family, with family members occupying most board seats. In most family-owned businesses, all important positions are filled by family members, reflecting the philosophy that enterprise is the family, and family is the enterprise.

Family members usually have a strong sense of trust among themselves, and there is almost no concern about the agency costs created by principal-agent relationships. This situation is very beneficial to the initial development of these companies. After these private enterprises go public, the founder's equity is often diluted, but the founders of most companies are still the major shareholders. The board meetings of these companies can easily be dominated by the “one voice” of the largest shareholder, severely limiting the role of other directors. The effectiveness of collaboration among the shareholders' meeting, the board of directors, and the board of supervisors typically needs to be improved.

The Relationship Governance Model of Private Enterprises

Corporate governance research has long recognized that contractual relations among stakeholders alone often cannot solve all issues related to corporate transactions, in part due to the incompleteness of contracts and the cost and failure of enforcing contractual agreements (Coase, 1937; Williamson, 1981). Relationship governance refers to the governing of transactions through some relational rules and informal contracts; it complements contractual governance. Relational rules are social processes and rules that exist because of the exchange relations between two parties (Powell and DiMaggio, 1991). Social processes include social interaction, information exchange, and so on; social rules include trust and punishment. The governance model of Chinese private enterprises reflects the characteristics of relationship governance more than contractual governance. This is because an important feature of Chinese private enterprises is the extensive involvement of family members.

In family businesses in China, due to the special relationships among the “contractors,” the supervision and execution of the company's responsibilities, rights, and interests are often not dependent on third parties, but rather are based on the status of and substantive relations among family members or pan-family members. Specifically, a fundamental relationship governance model is to govern according to the emotional and obligatory relationships among family members. Many family businesses have relied on the common struggle and sacrifice of family members. The emotional relationship and the sense of obligation are the source of their loyalty and cohesiveness. Accordingly, in subsequent management of the family business, the founders tend to assign resources and power to family members in their favor.

Another important aspect of family businesses' relationship governance is the development of a mutually trusting and mutually beneficial network of contacts, following the “differential pattern” (Fei, 1948). The differential pattern describes the characteristics of China's rural social relations. It refers to the network of countless personal relationships, like a spider web with the self at the center. Like the ripple of water triggered by casting a stone into a lake, social relationships with others become weaker as they get further away from the center. That is, the emotional intensity, social closeness, and trust associated with a social relationship decrease as the contact becomes more distant from the self in the social network of personal relationships. Fei assumes that this differential pattern is developed based on the reciprocal nature of trust and favor-rendering. Chinese private enterprises place great emphasis on family-based relationships. These family relationships can expand to further include friends and acquaintances of family members. On the basis of the family network, Chinese private enterprises have gradually developed a pan-family network and established trust with long-term contacts and important figures, making them a part of their own social relations.

Another major characteristic of private enterprises' relationship governance is the role of founders' authority in the allocation of resources. The founders of family businesses typically have established authority within the company through equity, innovation, and entrepreneurial activities. With the prevalence of relationship governance among Chinese private enterprises, family authority has its positive effects, but these enterprises need to adapt to the different rules and regulations for listed companies when they go public. Specifically, while the parental authority in family businesses promotes self-adaptability and self-adjustment in internal division of labor and cross-divisional cooperation, it also weakens the family business's ability to integrate external resources, experience, and other social capital, limiting the innovation ability of these firms. In addition, while the parental authority in family businesses often helps ensure the stability of organizational structure, often it is not easy to implement a standardized decision-making process due to special considerations of family members' needs. Especially for private enterprises that have already been listed, whether the relationship governance model can be integrated with the contractual governance model of public companies is key to their sustainable development.

Succession at Private Enterprises

In recent years, inheritance of private enterprises has caused widespread concern in Chinese society. According to the findings of Li (2013), the total number of private enterprises in China has accounted for 96 percent of the total number of enterprises in the country, of which 85.4 percent are family businesses, and the average age of founders of family companies has reached 52 years. In the next few years, private enterprises, especially family businesses, will need to address the challenges of inheritance and succession. However, data show that the average success rate of the second generation's successions is 40 percent, and the average success rate of the third generation's successions is only 4 percent (Li, 2013). Therefore, whether or not Chinese private enterprises can smoothly transition from the older generation of entrepreneurs to the younger generations has become an urgent issue.

The Evaluation of the Boards of Directors of Chinese Listed Companies

Nankai Corporate Governance Evaluation System

Li (2001) took the lead in proposing and developing the Corporate Governance Principles of Chinese Companies and International Comparison, after considering prevailing corporate governance principles, China's legal and institutional environments, and the actual situation of Chinese listed companies' governance. In 2003, Li and his team further introduced the first governance evaluation system for listed companies in China. The evaluation system specified indicators of listed companies' corporate governance quality along six dimensions: (1) shareholders' rights and interests, (2) governance of boards of directors, (3) governance of boards of supervisors, (4) governance of top executives, (5) information disclosure, and (6) relationship with stakeholders (Li, 2003). Since then, Professor Li's team has evaluated the governance conditions of Chinese listed companies for 16 consecutive years, and the index they developed is widely known as the Nankai Corporate Governance Index. Research findings based on this index have been referenced in the Code of Governance of Listed Companies (issued in 2002, revised in 2018) promulgated by China's Securities Regulatory Commission. In this chapter, we focus on describing the Board Governance Index, a key component of the Nankai Corporate Governance index.

Evaluation indicators. The Board Governance Evaluation System for Listed Companies in China was created mainly from the perspective that boards need to be inclusive, independent, and efficient in operations. On the premise that the board of directors must fully fulfill the fiduciary responsibility assigned to it by the shareholders' meeting, and at the same time effectively complete its entrustment responsibilities, Li and colleagues set up an evaluation index for board governance based on five dimensions: (1) director rights and obligations, (2) board operational efficiency, (3) board structure, (4) director compensation, and (5) board independence. Table 58.3 provides a detailed explanation of these indicators of board governance quality. A detailed description of these indicators can be found in Li and Zhang (2005).

Evaluation criteria. After conducting comprehensive reviews of relevant theories and empirical evidence and considering the requirements of Chinese laws and regulations, Li's team mainly adopted the standards articulated in their Corporate Governance Principles of Chinese Companies and International Comparison (2001) as the criteria for the above indicators of board governance. This evaluation system assigns numerical values to each sub-indictor, ranging from 0 percent to 100 percent, and then assigns weights to each sub-indictor according to its importance in the process of aggregation. The weights were determined after surveying corporate governance experts in China.

Table 58.3 Nankai's Board Governance Evaluation System

| Main factor | Sub-factor | Explanation | |

| Director rights and obligations | Directors' background, training, board composition, performance as directors, and turnover | Reflecting the status of directors, integrity, and performance | |

| Board operation efficiency | Board size, age and gender structure of the board, board meeting | Reflecting the fulfillment of the functions and roles of the board | |

| Board Governance Index (CCGINKBOD) | Board structure | Leadership structure of the board, establishment of special committees, operating status of special committees | Reflecting the efficiency and independence of the board of directors |

| Director remuneration | Directors' compensation level and structure, directors' performance evaluation | Measuring the incentives provided by the level and composition of directors' compensation | |

| Board independence | Proportion of independent directors, incentives for independent directors, independence | Reflecting the status of the independent director system |

It is worth mentioning that the Board Governance Index developed by Li's team not only incorporates related insights generated by developed countries but also considers the specific conditions of Chinese firms' corporate governance. The Board Governance Evaluation System includes multiple layers of indicators that are linked to the larger Corporate Governance Evaluation System, making the former an integral part of the latter. The board evaluation system not only relies on public information about listed firms but also incorporates subjective evaluations by corporate governance experts in China (Li, 2003; Zhang, 2008). For example, in the process of designing the evaluation index system, Li's team considered many other experts' suggestions (e.g., through seminars and other formats).

Evaluation of Chinese Listed Companies' Board Governance

Using public records such as annual reports of listed companies, since 2003 Li's team has continuously evaluated the governance status of the board of directors of Chinese listed companies. The evaluation results reflect the quality and trends of board governance of listed companies in China.

Overall Board Governance of Listed Companies in 2018 In 2018, the sample size of listed companies in China was 3,464. There were 1,075 listed companies that were state-owned enterprises (i.e., owned by the state). The average board governance index was 64.28, and the standard deviation was 2.31. The sub-index of board structure has the highest average value, followed by the sub-indexes of board operational efficiency, director rights and obligations, and director remuneration. The board independence sub-index has the lowest average value. These statistics show that the organizational structure of the boards of directors of Chinese listed companies is better than other aspects of board governance, and the efficiency of the boards of directors is relatively high. However, the independent director system is still the focal area for future improvements in board governance of listed companies in China. (See Table 58.4.)

Table 58.5 reports summary statistics of the board governance index and the sub-indexes by ownership type. It shows that the average level of board governance index of privately held, foreign-controlled, and state-controlled companies are in the middle; they are 64.47, 64.04, and 63.87, respectively. The quality of board governance of listed companies controlled by collectives, social groups, and employees is relatively poor, with average values of the board governance index at 63.74, 63.62, and 61.41, respectively. The privately held listed companies are overall better than the state-controlled listed companies. However, state-controlled companies are better in terms of board structure, board independence, and board operational efficiency. Privately held listed companies outperform state-owned companies in terms of director rights and obligations and director remuneration, especially in terms of directors' compensation incentives.

Table 58.4 Descriptive Statistics on the Overall Situation of Board Governance of Listed Companies in China in 2018

| Index | Mean | Median | S.D. | Range | Mini | Max |

| Board governance | 64.28 | 64.44 | 2.31 | 22.69 | 51.26 | 73.95 |

| Director rights and obligations | 61.81 | 61.75 | 4.85 | 29.00 | 46.50 | 75.50 |

| Board operational efficiency | 66.96 | 66.41 | 4.19 | 26.16 | 48.30 | 74.46 |

| Board structure | 69.00 | 70.00 | 6.88 | 79.50 | 17.50 | 97.00 |

| Director remuneration | 61.56 | 61.50 | 5.90 | 26.50 | 50.00 | 76.50 |

| Board independence | 60.96 | 61.00 | 4.59 | 28.25 | 44.25 | 72.50 |

Data source: Nankai University Corporate Governance Database.

Table 58.5 Descriptive Statistics of Board Governance by Ownership Type in 2018

| Controlling shareholders | N | Percent (%) | Board governance index | Director rights and obligations | Board operational efficiency | Board structure | Director remuneration | Board independence |

| State | 1,075 | 31.03 | 63.87 | 61.48 | 68.08 | 69.27 | 57.80 | 61.17 |

| Collectives | 16 | 0.46 | 63.74 | 60.16 | 68.08 | 67.31 | 62.72 | 58.78 |

| Private owners | 2,243 | 64.75 | 64.47 | 62.02 | 66.38 | 68.90 | 63.35 | 60.88 |

| Social organizations | 17 | 0.49 | 63.62 | 61.60 | 66.90 | 69.00 | 57.18 | 62.01 |

| Foreign investors | 66 | 1.91 | 64.04 | 59.49 | 67.65 | 68.69 | 61.49 | 60.56 |

| Employees | 4 | 0.12 | 61.41 | 60.69 | 67.20 | 48.13 | 63.88 | 64.56 |

| Others | 43 | 1.24 | 65.35 | 62.97 | 68.15 | 70.29 | 63.76 | 60.81 |

| Total | 3,464 | 100.00 | 64.28 | 61.81 | 66.96 | 69.00 | 61.56 | 60.96 |

Data source: Nankai University Corporate Governance Database.

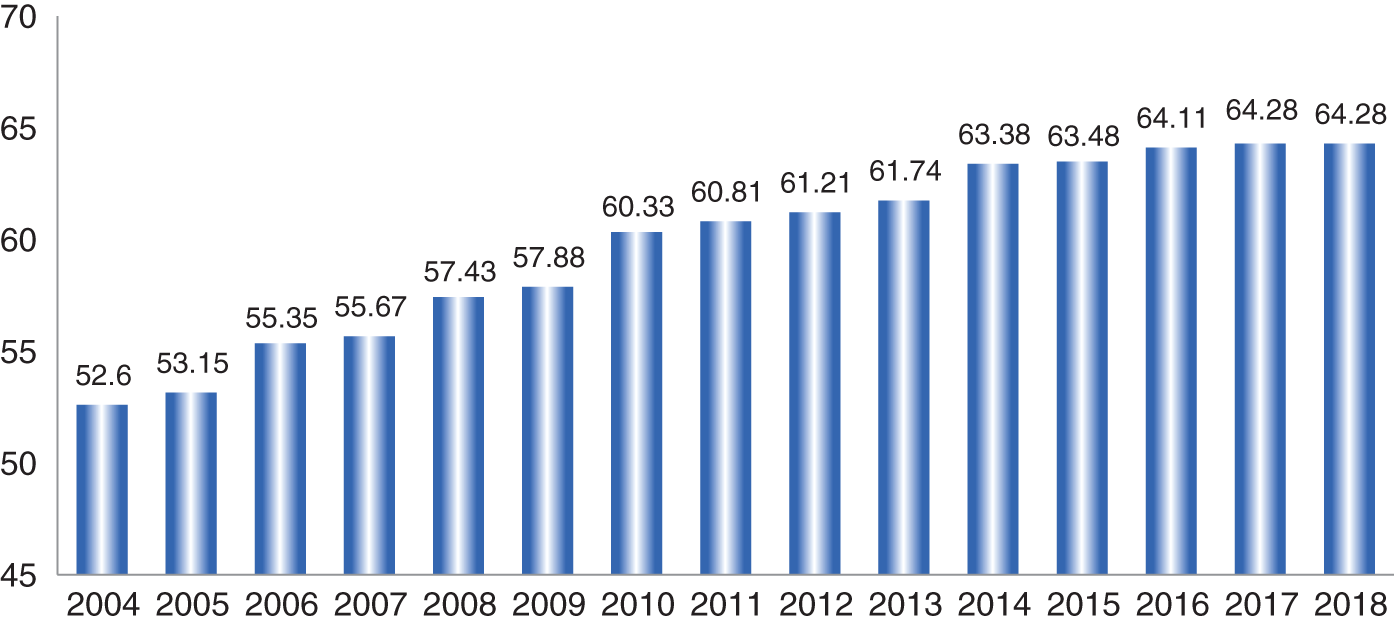

Trends in Board Governance of Chinese Listed Firms, 2004–2018 From the sample of 1,149 listed companies in 2004 to the sample of 3,464 listed companies in 2018, the evaluation of board governance of listed companies has undergone 15 years of development. The average level of the board governance index has shown an overall upward trend during those years. It rose year by year and reached its highest level in 2018, from 52.60 in 2004 to 64.28 in 2018. Figure 58.1 shows this overall trend.

According to the five sub-indexes of board governance, board operating efficiency and board independence have remained relatively stable in the past 15 years. The average operating efficiency index is relatively high, but shows no significant improvement during this period. Board structure and director rights and obligations have been improved most. Director rights and obligations and director compensation have always been weak areas of board governance. In the past five years, the overall level of the board governance index has shown a trend of slowed improvement, indicating that board governance improvement is probably facing some bottlenecks in recent years. (See Table 58.6.)

FIGURE 58.1 Average Level of Board Governance Index of Chinese Listed Companies Over Time

Data source: Nankai University Corporate Governance Database.

When comparing the board governance indexes of companies with different types of controlling shareholders, we can see from Table 58.7 that state-controlled companies scored better than privately held listed companies in 2004 through 2008 and in 2010, but worse than privately held companies in 2009 and after 2011. Table 58.7 also shows that in recent years privately held companies have outperformed state-owned companies in terms of director remuneration and director rights and obligations, but underperformed state-controlled companies in terms of board structure and board operational efficiency. This shows that the boards of directors of state-controlled listed companies emphasize compliance, but privately held listed companies have more advantages in the construction of effective governance mechanisms.

Main Conclusions Overall, the board governance index of listed companies in China shows that the average score in 2018 was 64.28, the same as in 2017. However, there were significant changes in the sub-indexes for director rights and obligations, board operational efficiency, and director remuneration. From 2004 to 2018, board governance improved considerably along all dimensions, especially the board structure index, which improved from 47.81 in 2004 to 69.00 in 2018, more than any other sub-index. This shows that over the past 15 years, board governance has improved most in terms of compliance with regulations, shown by remarkable increases in the sub-indexes of board structure and director rights and obligations. In contrast, further improvements are needed in terms of board independence, board operational efficiency, and director remuneration. State-owned companies performed better than privately owned companies in the early years, but privately owned companies consistently outperformed state-owned companies in more recent years. Specifically, privately owned companies demonstrated better board governance in the areas of director rights and obligations and director remuneration and were more sensitive to market conditions. In contrast, state-owned companies performed better in areas that reflect compliance to regulations.

Table 58.6 Comparison of the Average Value of the Board Governance Index of Chinese Listed Companies Over the Years

| Year | Board governance index | Director rights and obligations | Board operational efficiency | Board structure | Director remuneration | Board independence |

| 2004 | 52.60 | 44.38 | 62.42 | 47.81 | 48.49 | 59.37 |

| 2005 | 53.15 | 46.04 | 59.17 | 46.29 | 45.86 | 56.59 |

| 2006 | 55.35 | 53.26 | 59.41 | 55.83 | 44.79 | 57.03 |

| 2007 | 55.67 | 53.62 | 59.74 | 55.80 | 45.76 | 57.17 |

| 2008 | 57.43 | 60.06 | 58.24 | 56.05 | 56.60 | 57.33 |

| 2009 | 57.88 | 61.63 | 63.16 | 60.36 | 47.55 | 57.38 |

| 2010 | 60.33 | 65.09 | 57.66 | 67.94 | 55.56 | 58.82 |

| 2011 | 60.81 | 66.43 | 57.40 | 68.38 | 57.14 | 58.88 |

| 2012 | 61.21 | 65.17 | 57.19 | 68.52 | 58.50 | 59.97 |

| 2013 | 61.74 | 63.71 | 58.44 | 68.70 | 59.30 | 60.63 |

| 2014 | 63.38 | 67.17 | 60.74 | 69.03 | 59.56 | 63.05 |

| 2015 | 63.48 | 61.73 | 67.51 | 68.45 | 57.92 | 60.61 |

| 2016 | 64.11 | 61.73 | 66.79 | 68.77 | 60.57 | 61.49 |

| 2017 | 64.28 | 62.94 | 66.97 | 68.89 | 60.81 | 61.21 |

| 2018 | 64.28 | 61.81 | 66.96 | 69.00 | 61.56 | 60.96 |

Data source: Nankai University Corporate Governance Database.

Table 58.7 Comparison of the Average Value of the Board Governance Index of State-Owned and Privately Held Companies Over the Years

| Year | Controlling shareholder | Board governance index | Director rights and obligations | Board operation efficiency | Board structure | Director remuneration | Board independence |

| 2004 | State | 52.73 | 44.41 | 62.32 | 47.88 | 48.67 | 59.61 |

| Private | 52.25 | 44.49 | 62.59 | 48.25 | 47.80 | 58.50 | |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| 2014 | State | 63.32 | 67.87 | 60.64 | 69.16 | 59.56 | 62.51 |

| Private | 63.46 | 66.73 | 60.79 | 68.99 | 59.66 | 63.43 | |

| 2015 | State | 63.20 | 60.93 | 68.37 | 68.62 | 55.53 | 60.74 |

| Private | 63.71 | 62.37 | 66.91 | 68.44 | 59.62 | 60.54 | |

| 2016 | State | 63.77 | 60.77 | 67.74 | 68.98 | 58.03 | 61.42 |

| Private | 64.35 | 62.41 | 66.21 | 68.72 | 62.12 | 61.56 | |

| 2017 | State | 64.03 | 62.42 | 68.22 | 69.08 | 57.48 | 61.70 |

| Private | 64.42 | 63.31 | 66.22 | 68.82 | 62.65 | 60.94 | |

| 2018 | State | 63.87 | 61.48 | 68.08 | 69.27 | 57.80 | 61.17 |

| Private | 64.47 | 62.02 | 66.38 | 68.90 | 63.35 | 60.88 |

Data source: Nankai University Corporate Governance Database.

Conclusions

In the past 40 years of China's economic reform and opening up, along with the establishment of a modern enterprise system, the concept of corporate governance has received increasing attention from all stakeholders. The process of Chinese enterprise reform is a process of evolution from administrative governance to economic governance, reflecting the gradual weakening of administrative governance and the gradual strengthening of economic governance. At the end of 2017, all Chinese central enterprises were reformed into modern corporations, reflecting the ideology of reform toward economic governance. The overall purpose of enterprise reform is to deepen the economic reform of state-owned parent companies and remove the residuals of the planned economy and the administrative governance model, allowing the market to play a more significant role in resource allocation.

The analysis of board governance of state-owned companies in China shows that board governance performs well in terms of compliance but needs further improvement in terms of director remuneration incentives and board operational efficiency. In our opinion, the focus of future board governance reform should include four things: (1) rationalizing the rights and responsibilities associated with state ownership, encouraging co-ownership by the state and private investors, and further advancing the transition of state-owned enterprises from relying on the administrative mode of governance to using the economic mode of governance; (2) improving the governance of the board of directors of state-owned enterprises, effectively implementing the independent decision-making power of the board, and strengthening the decision-making and supervision functions of the board; (3) encouraging privately owned companies to develop the relational governance model to further integrate practices that reflect governance by contracts, especially establishing efficient board operations that allow family members and professional managers to complement and cooperate with one another; and (4) improving the external environment of corporate governance and deepening reforms of related governance systems to enable the transition of board governance from the administrative model to the economic model.

About the Authors

David H. Zhu is Dean's Council Distinguished Scholar and associate professor in management and entrepreneurship at the W. P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State University. Zhu's research examines how top executives' cognitions, values, personalities, experiences, and networks influence their strategic decisions, including decisions related to corporate strategy, corporate governance, innovation and entrepreneurship, and dynamic capabilities. His research has won numerous prestigious awards from major scholarly associations in the world, such as the William Newman Award and the Louis Pondy Award from the Academy of Management and the Best Paper Award from the Strategic Management Society.

Zhu serves on the editorial boards of four of the world's top management journals, namely Administrative Science Quarterly, Academy of Management Review, Academy of Management Journal, and Strategic Management Journal. His work has been widely published on these top journals and reported by popular media such as the Wall Street Journal. He is a representative-at-large of the Strategic Management Society, chair of the award committee and representative-at-large of the International Association for Chinese Management Research, and a member of the executive committee of the Chinese Management Scholars' Community. Zhu has worked as an educator or advisor to top executives of many leading Chinese companies. He has also served as a keynote speaker, panelist, and expert discussant in a variety of forums, conferences, and academic and executive gatherings.

Weian Li, PhD in management and PhD in economics, is China's first Chang Jiang Scholar Distinguished Professor in management. He is dean of China Academy of Corporate Governance (CACG) in Nankai University and Tianjin University of Finance and Economics. He is also the chief editor of the Encyclopedia of China—Business Administration. He serves as the co-president of Chinese Academy of Management, vice president of the Chinese Institute of Business Administration, vice chairman of Business Administration Teaching and Instruction Committee of the Ministry of Education in China, and a member of National Enterprise Compliance Committee, among other leadership roles. He also served as the president of Dongbei University of Finance and Economics, the president of Tianjin University of Finance and Economics, the convener of the Program Appraisal Group of the Sixth Academic Degrees Committee of the State Council in China (Business and Administration area), dean of Business College in Nankai University, and chief editor of Nankai Business Review.

Prof Li has been conducting research on corporate governance, network organization, enterprise group governance, and green governance in China for a long time. He led his team to develop the first Chinese corporate governance evaluation index system, the barometer of the governance quality of listed companies in China, and has published the Chinese Corporate Governance Evaluation Report and China Corporate Governance Index (CCGINK). Prof. Li and his research team issued the first Green Governance Principle around the world in 2017 and developed China Green Governance Index (CGGI) for Chinese listed companies.

He has received many prestigious awards, including the Sun Yefang Economic Science Award, the JiangYiwei Enterprise Reform and Development Award, China Management Science Award, First Class Prize of the China Academic Social Sciences Outstanding Achievement Award (rewarded by the Ministry of Education of China), among others.

Yaowei Zhang is an associate professor in the Business School of Nankai University. He holds a PhD in business administration and a postdoctoral certificate in applied economics. He is the director of Green Governance Department of China Academy of Corporate Governance (CACG) in Nankai University, and a reviewer of Nankai Business Review, among others. He is also a member of the Chinese Academy of Management and of the International Association for Chinese Management Research, among others.

Prof Zhang's research area includes corporate governance, financial institution governance, and green governance in China. He is the core member of the corporate governance evaluation team that first developed the Chinese corporate governance evaluation index system, and of the green governance team that developed China Green Governance Index (CGGI) for Chinese listed companies. He has led several high-level research programs, including two research projects funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China. For decades, he has published many papers in top journals such as the Management World, and has received the Second Class Prize of the China Academic Social Sciences Outstanding Achievement Award and Third Class Prize for Excellent Achievements in Social Science Research in Tianjin.

References

- Berle, A. A., and G. C. Means. 1967. The Modern Corporation and Private Property, 2nd ed. Harcourt, Brace & World, New York.

- Coase, R. 1937. The Nature of the Firm. Economica, 4(16): 386–405.

- Donaldson, T., and L. E. Preston. 1995. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Academy of management Review, 20(1): 65–91.

- Fama, E. F., and M. C. Jensen. 1983. Separation of Ownership and Control. Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2): 301–325.

- Fei, X. 1948. Rural China. Beijing, Peking.

- Freeman, R. E. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Jensen, M. C., and W. H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4): 305–360.

- Li, Y., X. Zhao, and H. Li. 2001. Research on the Relations Between Board Structure and Firm Performance, China Industrial Economy, (5): 48–54 (in Chinese).

- Li, W. 2001. Corporate Governance Principles of Chinese Companies and International Comparison, China Financial & Economic Publishing House (in Chinese).

- Li, W. 2003. A Study of Appraisal System of Corporate Governance for Chinese Listed Companies, Nankai Business Review, 3:4–22 (in Chinese).

- Li, W. 2013. The Inheritance and Construction of Private Enterprises' Governance Mechanism, Nankai Business Review, 16(3):1 (in Chinese).

- Li, W. 2016a. Green Governance: Governance View beyond Countries, Nankai Business Review, 19(6):1 (in Chinese).

- Li, W. 2016b. Independence: The Foundation of Governance Effectiveness, Nankai Business Review, 19(3):1 (in Chinese).

- Li, W., and Y. Zhang. 2005. An Empirical Study on the Evaluation of the Board Governance of China's Listed Companies, Modern Economic Science, 27(1):17–23 (in Chinese).

- Lu, Z., and S. Hu. 2015. Agency Conflict Between Stockholder and Manager and the Governance Role of Non-executive Directors, Management World, (1):129–138 (in Chinese).

- Ma, L. 2003. A Study on the Board Evaluation Index System in Assessing Corporate Governance, Nankai Business Review, 6(3):15–17 (in Chinese).

- Powell, W. W., and P. J. DiMaggio (eds.). 1991. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Useem, M., H. Singh, N. Liang, and P. Cappelli. 2017. Fortune Makers: The Leaders Creating China's Great Global Companies. Public Affairs, New York.

- Williamson, O. E. 1981. The Economics of Organization: The Transaction Cost Approach, American Journal of Sociology, 87(3): 548–577.

- Ye, K., J. Zhu, Z. Lu, and R. Zhang. 2011. The Independence of Independent Directors: Evidence from Board Voting Behavior, Economic Research Journal, 1:126–139 (in Chinese).

- Zhang, Y. 2008. An Empirical Study of Board Governance, Corporate Governance Index and Firm Performance of Listed Companies, Journal of Management Science, 21:11–18 (in Chinese).