8

English Intonation – Form and Meaning

JOHN M. LEVIS AND ANNE WICHMANN

Introduction

Intonation is the use of pitch variations in the voice to communicate phrasing and discourse meaning in varied linguistic environments. Examples of languages that use pitch in this way include English, German, Turkish, and Arabic. The role of pitch in intonation languages is to be distinguished from its role in tone languages, where voice pitch also distinguishes meaning at the word level. Such languages include Chinese, Vietnamese, Burmese, and most Bantu languages. The aims of this chapter are twofold: firstly, to present the various approaches to the description and annotation of intonation and, secondly, to give an account of its contribution to meaning.

Descriptive traditions

There have been many different attempts to capture speech melody in notation: the earliest approach, in the eighteenth century, used notes on staves, a system already used for musical notation (Steele 1775– see Williams 1996). While bar lines usefully indicate the phrasing conveyed by intonation, the stave system is otherwise unsuitable, not least because voice pitch does not correspond to fixed note values. Other less cumbersome notation systems have used wavy lines, crazy type, dashes, or dots to represent pitch in relation to the spoken text. See, for example, the representation in Wells (2006: 9) below, which uses large dots for accented syllables and smaller ones for unstressed syllables.

An important feature of intonation is that not all elements of the melody are equally significant; the pitch associated with accented syllables is generally more important than that associated with unstressed syllables. This distinction is captured in the British system of analysis, which is built around a structure of phrases (“tone groups”) that contain at least one accented syllable carrying pitch movement. If there are more than one, the last is known as the “nucleus” and the associated pitch movement is known as the “nuclear tone”. These nuclear tones are described holistically as falling, rising, falling-rising, rising-falling, and level (Halliday proposed a slightly different set, but these are rarely used nowadays), and the contour also extends across any subsequent unstressed syllables, known as the tail. A phrase, or tone group, may also contain additional stressed syllables, the first of which is referred to as the onset. The stretch from the onset to the nucleus is the “head” and any preceding unstressed syllables are prehead syllables. This gives a tone group structure as follows: [prehead head nucleus tail] in which only the nucleus is obligatory. The structure is exemplified in the illustration above.

In the British tradition, nuclear tones are conceived as contours, sometimes represented iconically in simple key strokes [fall , rise /, fall-rise /, rise-fall/, level -] inserted before the syllable on which the contour begins. This is a useful shorthand as in the following: I’d like to thank you | for such a /wonderful experience |. In American approaches, on the other hand, pitch contours have generally been decomposed into distinct levels or targets, and the resulting pitch contour is seen as the interpolation between these points. In other words, a falling contour is the pitch movement between a high target and a low(er) target. These traditions, especially in language teaching, have been heavily influenced by Kenneth Pike (1945), whose system described intonation as having four pitch levels. Each syllable is spoken at a particular pitch level and the pattern of pitches identified the type of intonation contour. The primary contour (the British “nucleus” or the American “final pitch accent”) is marked with ° . The highest possible pitch level is 1 and the lowest is 4. In the illustration below, Pike analyzed a possible sentence in two ways.

Both of these sentences are accented on the word home and both fall in pitch. Pike describes them as having different meanings, with the second (starting at the same level as home) as portraying “a much more insistent attitude than the first” (Pike 1945: 30). Intonational meaning, to Pike, was tightly bound up with communicating attitudes, and because there were many attitudes, so there had to be many intonational contours. A system with four pitch levels provided a rich enough system to describe the meanings thought to be communicated by intonation. Later researchers showed that Pike’s system, ingenious as it was, overrepresented the number of possible contours. For example, Pike described many contours that were falling and argued that they were all meaningfully distinct. The 3-2°-4 differed from the 2-2°-4, 1-2°-4, 3-3°-4, 2-3°-4, 3-1°-4, etc., although there is little evidence that English has so many falling contours with distinct meanings – the differences are more likely to be gradient ones expressing different degrees of affect. The system begun by Pike is used widely in American pronunciation teaching materials, including in the influential textbook Teaching Pronunciation (Celce-Murcia, Brinton, and Goodwin 2010).

Like the American tradition based on Pike’s four pitch levels, the British system of nuclear tones has played a role in research (Pickering 2001) but more widely in teaching (e.g., O’Connor and Arnold 1973; Bradford 1988; Brazil 1994; Wells 2006).

The American notion of treating contours not holistically, as in the British tradition, but as a sequence of levels or targets, was developed further by Janet Pierrehumbert (1980), and this system forms the basis of the kind of analysis that is now most widely used in intonation research. It posits only two abstract levels, High (H) and Low (L). If the target is associated with a prominent (accented) syllable, the “pitch accent” is additionally marked with an asterisk [*], thus giving H* or L*. A falling nuclear tone would therefore be represented as H* L, in other words the interpolation between a high pitch accent (H*) and a low target (L), and a falling-rising tone would be represented as H* L H. Additional diacritics indicate a target that is at the end of a nonfinal phrase or the end of the sentence before a strong break in speech: intermediate phrases and intonational phrases.

This kind of analysis, referred to as the Autosegmental Metrical approach (see Ladd 1996) is now the norm in intonation research. Much of this research has been driven by the needs of speech technology, where a binary system (H and L) lends itself more readily to computer programming than any holistic analysis such as the British nuclear tone system. In addition, it leads to an annotation system that is easy to use in conjunction with instrumental analysis. However, while this combination of autosegmental phonology and acoustic analysis is common in speech research, it is not as common among applied linguists, where earlier American or British systems, e.g., Pike’s four pitch levels, the British system of nuclear tones, together with auditory (impressionistic) analysis, remain the norm. This may be because these systems have a longer history, it may be because of their usefulness in language teaching, or it may be because applied researchers do not have familiarity with the research into intonation being carried out by theoretical and laboratory phonologists. The number of applied linguistic studies that have appealed to newer models of intonation is quite limited. Researchers such as Wennerstrom (1994, 1998, 2001) and Wichmann (2000) have provided accessible accounts of the pitch accent model for the applied researcher, but their work has, by and large, not been widely emulated in research and not at all in language teaching.

It is unlikely that intonation studies will ever dispense entirely with auditory analysis, but the greatest advance in the study of intonation (after the invention of the tape recorder!) has come with the widespread availability of instrumental techniques to complement listening. The advent of freely available speech analysis software has revolutionized the field: published studies that do not make use of instrumental analysis are increasingly rare, and the ability to read and understand fundamental frequency contours in relation to waveform displays and sometimes spectrographic detail is an essential skill.

Instrumental analysis

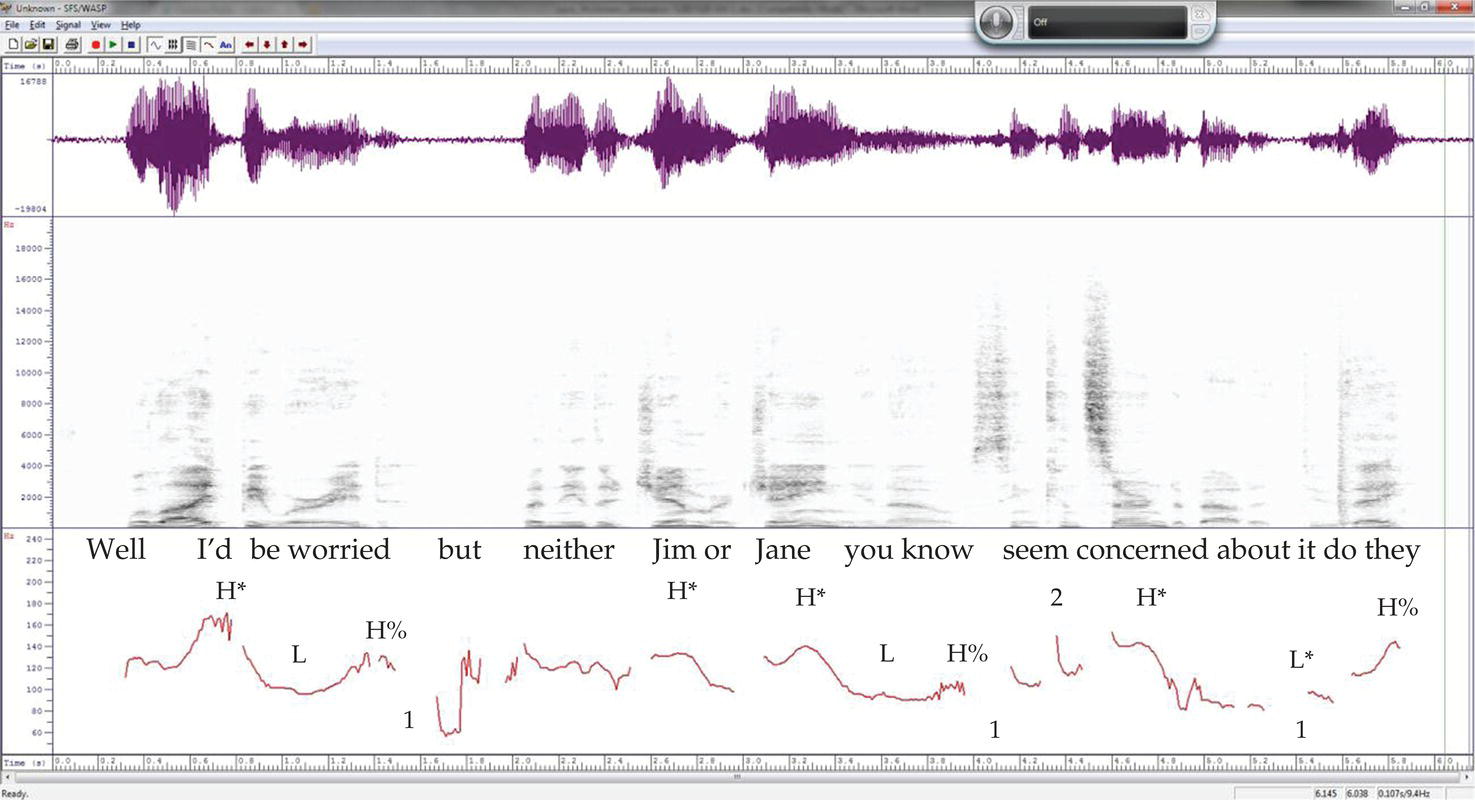

The acoustic analysis of intonation involves the use of speech processing software that visualizes elements of the speech signal. There are three main displays that are useful in the study of intonation: the waveform spectrograms, and in particular the fundamental frequency (F0) trace, which is what we hear as speech melody or pitch. Interpreting the output of speech software requires some understanding of acoustic phonetics and the kind of processing errors that may occur. Figure 8.1 shows three displays combined – F0 contour, spectrogram, and waveform. It also shows the fragmentary nature of what we “hear” as a continuous melody. This is due to the segmental make-up of speech: only sonorant segments carry pitch (vowels, nasals, liquids) while fricatives and plosives leave little trace.1 It is also common to see what seems like a sudden spike in pitch or short sequence much higher, or lower, than the surrounding contour. These are generally not audible to the listener. These are so-called “octave leaps”, which are software-induced errors in calculating the F0 and are sometimes caused by the noise of fricatives or plosives. These examples show that it takes some understanding of the acoustic characteristics of individual speech sounds to read F0 contours successfully.

Figure 8.1 Well, I’d be worried / but neither Jim or Jane / you know / seem concerned about it / do they?

An important advance in the development of speech analysis software has been to allow annotation of the acoustic display so that the annotation and the display (e.g., spectrogram, waveform, F0 contour) are time-aligned. The most commonly used software of this kind, despite being somewhat user-unfriendly for anyone who does not use it on a daily basis, is Praat (Boersma 2001). This allows for several layers of annotation, determined by the user. Usually the annotation is in terms of auditorily perceived phonological categories (falls, rises, or more often H*L, L*H, etc.), but separate tiers can be used for segmental annotation or for nonverbal and paralinguistic features (coughs, laughter, etc.).

Working with the output of acoustic analysis of intonation is clearly not straightforward: we need to understand on the one hand something of acoustic phonetics and what the software can do, but on the other hand we need to realize that what we understand as spoken language is as much the product of our brains and what we know about our language as of the sound waves that we hear. This means that computer software can show the nature of the sounds that we perceive, but it cannot show us what we make of it linguistically.

The linguistic uses of intonation in English, together with other prosodic features, include:

- Helping to indicate phrasing (i.e., the boundaries between phrases);

- Marking prominence;2

- Indicating the relationship between successive phrases by the choice of pitch contour (fall, rise, etc., or in AM terms the sequence of pitch accents). A phrase final fall can indicate finality or closure, while a high target such as the end of a rise or a fall-rise, can suggest nonfinality.

Phrases that make up an overall utterance are sometimes called tone units or tone groups. These correspond to a feature of the English intonation system called tonality (Halliday 1967). In language teaching, tone groups are often given other names as well, including thought groups or idea units, although such meaning-defined labels are not always helpful because it is not clear what constitutes an “idea” or a “thought”. Each tone unit contains certain points in the pitch contour that are noticeably higher than others. These are syllables that will be heard as stressed or accented in the tone group. In English, these have a special role. In Halliday (1967), these are called tonic syllables and their system is called tonicity. The contour associated with each phrase-final accent ends with either high or low. These are examples of tonality in Halliday’s system.

These three elements – phrasing, prominence placement, and contour choice – are part of intonational phonology. The H and L pitch accents are abstract – the phonology does not generally specify how high or how low, simply High or Low (or at best, higher or lower than what came before). However, the range of pitch over individual syllables, words, or longer phrases can be compressed or expanded to create different kinds of meaning. An expanded range on a high pitch accent can create added emphasis (it’s mine versus it’s MINE!), for example, or it can indicate a new beginning, such as a new paragraph or topic shift. A compressed pitch range over a stretch of speech, on the other hand, may signal parenthetical information.

The display in Figure 8.13 illustrates features of English intonation with the acoustic measurement of an English sentence of 21 syllables. The top of the display shows the waveform, the middle the spectrographic display, and the bottom the fundamental frequency (F0) or pitch display. We will discuss a number of features visible in this figure.

Phrasing – boundaries and internal declination

Firstly, the sentence has four divisions as seen by the breaks in the pitch lines (marked with the number 1). These are, in this case, good indications of the way in which the sentence was phrased. It is important to note, however, that not all phrases are separated by a pause. In many cases the analyst has to look for other subtle signals, including pitch discontinuity and changes of loudness and tempo (“final lengthening”) and increased vocal fry (“creak”) to find acoustic evidence of a perceived boundary.

There is a second element of intonation present in this sentence, and that is the tendency of voice pitch to start high in a tone group and move lower as the speaker moves through the tone unit. This is known as declination and is clearest in the second tone group, which starts relatively high and ends relatively low in pitch. Related to this is the noticeable reset in pitch at the beginning of the next tone group (marked with 2). The only phrase to reverse this is the final phrase, which is a tag question. Tag questions can be realized with a fall or a rise, depending on their function. The rising contour here suggests that it is closer to a real question than simply a request for confirmation.

Prominence

The next linguistic use of pitch in English is the marking of certain syllables as prominent. In the AM system, these prominent syllables are marked as having starred pitch accents. Pitch accents (or peak accent; see Grice 2006) are, at their most basic, marked with either High pitch (H*) or Low pitch (L*).

This corresponds to other terminology including (in the British system): tonic (Halliday 1967), nuclear stress (Jenkins 2000), sentence stress (Schmerling 1976), primary phrase stress (Hahn 2004), focus (Levis and Grant 2003), prominence (Celce-Murcia, Brinton, and Goodwin (2010), highlighting (Kenworthy 1987), and selection (Brazil 1995), among others. The perception of prominence is triggered primarily (in English) by a pitch excursion, upwards or occasionally downwards. Again, pitch works together with other phonetic features in English to signal prominence, especially syllable lengthening and fuller articulation of individual segmentals (vowels and consonants), but pitch plays a central role in marking these syllables. The pitch excursions are often visible in the F0 contour – in Figure 8.1 they are aligned with the accented syllables; I’d, Jim, Jane and the second syllable of concerned all have H* pitch accents and are marked with’ while do has a L* pitch accent – the beginning of a rising contour that reflects the questioning function of do they.

In the AM system, all pitch accents are of equal status, but the British system of nuclear tones reserves special significance for the last pitch accent in a phrase (or tone group). In the sentence in Figure 8.1, the second tone unit has two pitch accents, Jim and Jane. Jane would carry the nuclear accent, while the accent on Jim would be considered part of the Head.

The nuclear syllable is associated with the nuclear tone or pitch contour, described in holistic terms as a fall, a rise, or fall-rise, for example. The tone extends across any subsequent unstressed syllables up to the end of the tone group. In Figure 8.1 the nuclear fall beginning on I’d extends over be worried. This nuclear tone drops from the H* to an L pitch and then rises to the end of the tone group, with a final H% (the % means the final pitch level of a tone group). This is the kind of intonation that, when spoken phrase finally, “has a ‘but’ about it” (Cruttenden 1997; Halliday 1967: 141). That beginning on concerned extends over about it. Less easy to determine is the contour beginning on Jane: it could be a falling tone that flattens out over you know or, if the slight rise visible at the end of the phrase is audible, it could be another falling-rising contour (H*LH%, as marked) or a falling contour (H*LL%) extending across the three syllables Jane you know. Alternatively, the tone group can be seen as two tone groups, the first, but neither Jim or Jane followed by a separate phrase you know, particularly if the final item such as a discourse marker is separated by a slight pause – not the case here. In this analysis, you know would be an anomalous phrase with no nucleus and spoken at a low, level pitch with a slight rise or with a fairly flat contour. This kind of parenthetical intonation patttern was discussed by Bing (1980) and others (e.g., Dehé and Kavalova, 2007).

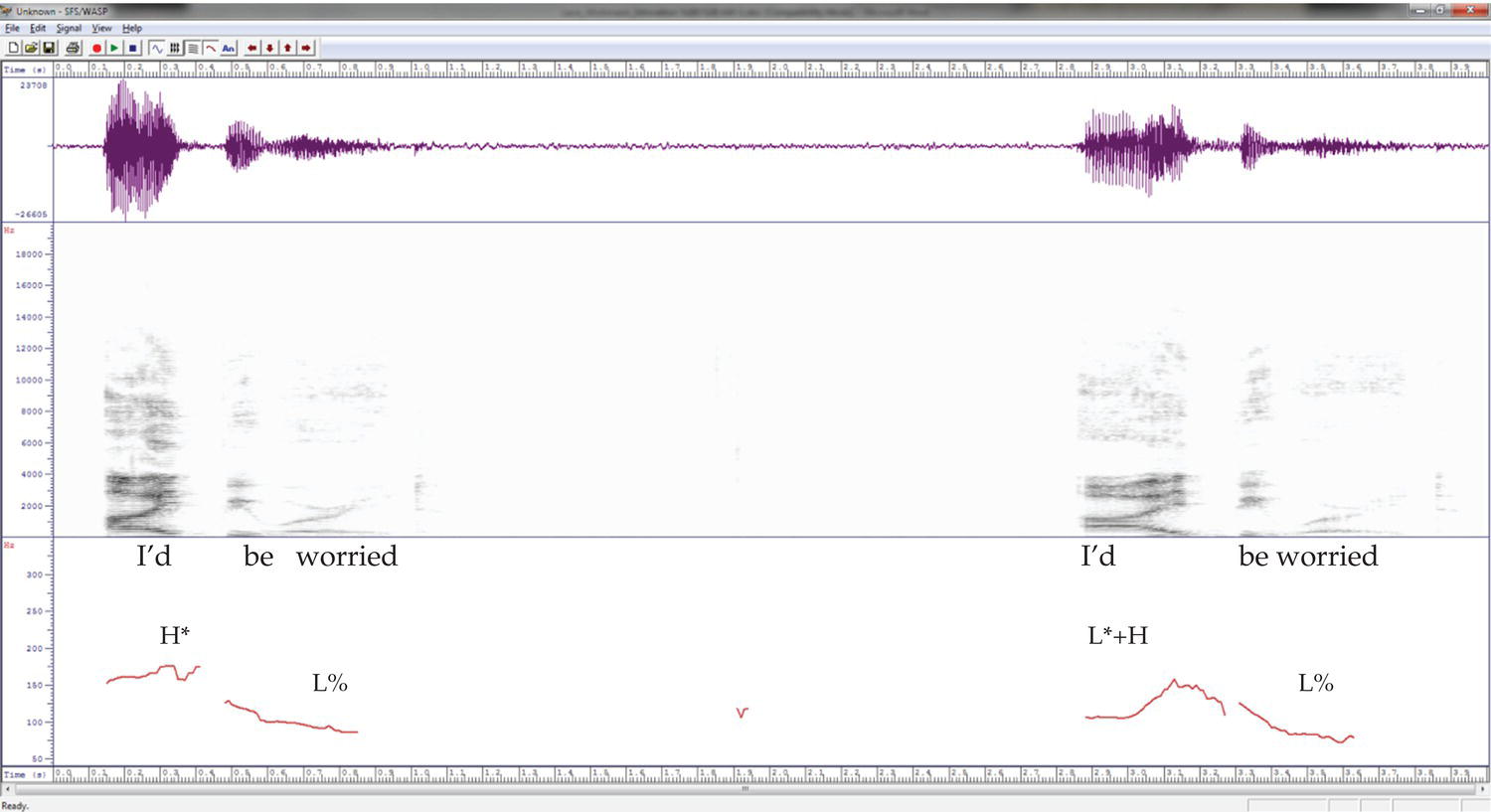

English also has other pitch accents that are characterized by the way that the prominent syllable aligns with the pitch accent. In the currently most fully developed system for transcribing intonation, the ToBI system, based on the work of Pierrehumbert (1980) and Beckman and Pierrhumbert (1986), English pitch accents can also be described as L+H*, L*+H, and H+!H*. These somewhat intimidating diacritics simply mean that the pitch accent is not perfectly aligned with the stressed syllable that is accented. In H* and L*, the vowel that is accented is aligned with the peak or lowest point of the pitch accent. This misalignment of pitch accent and stressed syllables is linguistically meaningful in English (see Ladd 2008; Pierrehumbert 1980; Pierrehumbert and Hirschberg 1992 for more information). Figure 8.2 shows the difference between the H* and L*+H pitch accent, which starts low on the word I but continues to a high pitch on the same syllable.

Figure 8.2 H* and L*+H pitch accents on I’d.

Discourse meaning

The sentence in Figure 8.1 has other features that are important in understanding English intonation. The first pitch accent, on I’d, is noticeably higher than the other pitch accents. This may be because it is first and because pitch declines across an utterance unless it is fully reset (Pierrehumbert 1980). An extra-high reset may also be connected to topic shifts (Levis and Pickering 2004; Wichmann 2000). In this case the expanded pitch range is most likely to be the result of contrastive stress – emphasizing I’d, presumably in contrast to someone else who is worried. The default position for a nucleus is the last lexical item of a tone group, and this means that the neutral pronunciation of I’d be worried would be to have the accent on worried. Here, however, the accent has been shifted back to I’d and worried has been de-accented. This has the effect of signaling that “being worried” is already given in that context and that the focus is on I’d. This is a contrastive use of accent and a de-accenting of given or shared information. The contrastive stress may also contain an affective element – emphasis is hard to separate from additional emotional engagement. However, we know that perceptions of emotion are not a function of intonation alone (Levis 1999).

In summary, linguistic uses of intonation in English include:

- The use of pitch helping to mark juncture between phrases.

- Pitch accents marking syllables as informationally important.

- De-accenting syllables following the final pitch accent. This marks information as informationally unimportant.

- Final pitch movement at the ends of phrases providing general meanings of openness or closedness of content of speech. These include pitch movement at the ends of intermediate and final phrases in an utterance.

- Extremes of pitch range marking topic shifts or parenthetical information.

Applications in applied linguistics

Acoustic analysis has been used to examine in fine phonetic detail some of the prosodic differences between languages, with important implications for both clinical studies and also the study of second language acquisition (e.g., Mennen 2007). An example of cross-linguistic comparison is the work on pitch range. It is commonly claimed that languages differ in the degree to which their speakers exploit pitch range and that these differences are cultural (e.g., Van Bezooijen 1995), in some cases giving rise to national stereotypes. However, such observations are often drawn from studies whose ways of measuring are not necessarily comparable. Mennen, Schaeffler, and Docherty (2012) examined the pitch range differences between German and English using a variety of measures and found that global measures of the F0 range, as used in many other studies, were less significant than measures based on linguistically motivated points in the contour. The claim, therefore, is not just a reflection of cultural differences but that “f0 range is influenced by the phonological and/or phonetic conventions of the language being spoken” (2012: 2258). Such findings have important implications for L2 acquisition: while some learners may indeed resist an F0 range if it does not accord with their cultural identity, the results of this study show that such cross-language differences in F0 range may also arise from difficulty in acquiring the intonational structure of the other language (2012). This may also be the case for disordered speech, where pitch range has been thought to be symptomatic of certain conditions. Here, too, it may be a case of inadequate mastery of the intonation system rather than its phonetic implementation.

Another area of study made possible by instrumental techniques is the close analysis of the timing of pitch contours in relation to segmental material. Subtle differences in F0 alignment have been found to characterize cross-linguistic prosodic differences. Modern Greek and Dutch, for example, have similar rising (pre-nuclear) contours but they are timed differently in relation to the segmental material (Mennen 2004). These differences are not always acquired by non-native speakers and contribute, along with segmental differences, to the perception of a foreign accent. Variation in alignment can also be discourse-related. Topic-initial high pitch peaks often occur later in the accented syllable – even to the extent of occurring beyond the vowel segment (Wichmann, House and Rietveld 2000), and our perception of topic shift in a spoken narrative may therefore be influenced not only by pitch height but also by fine differences in peak timing.

Experimental methods are now widely used to examine the interface between phonology and phonetic realization. This includes studies of timing and alignment, as described above, studies to establish the discreteness of prosodic categories underlying the natural variation in production, and also investigations into the phonetic correlates of perceived prominence in various languages. Such experiments sometimes use synthesized stimuli, whose variation is experimentally controlled, and sometimes they rely on specially chosen sentences being read aloud. Laboratory phonology, as it is called, has been seen as an attempt at rapprochement between phonologists who deal only with symbolic representation with no reference to the physics of speech, and the engineers who use signal- processing techniques with no reference to linguistic categories or functions (Kohler 2006). There are many, however, who criticize the frequent use of isolated, noncontextualized sentences, with disregard for “functions, contextualisation and semantic as well as pragmatic plausibility” (Kohler 2006: 124). Those who study prosody from a conversation analysis perspective have been particularly critical of these methods, rejecting both the carefully designed but unnatural stimuli and also the post hoc perceptions of listeners. The only valid evidence for prosodic function in their view is the behavior of the participants themselves. The experimental approach therefore, however carefully designed and however expertly the results are analysed, has from their perspective little or nothing to say about human interaction.

Intonation and meaning

By exploiting the prosodic resources of English it is possible to convey a wide range of meanings. Some meanings are conveyed by gradient, paralinguistic effects, such as changes in loudness, tempo, and pitch register. Others exploit categorical phenomena including phrasing (i.e., the placement of prosodic boundaries), the choice of tonal contour such as a rise or a fall, and the location of pitch accents or nuclear tones. It is uncontroversial that intonation in English and other intonation languages does not convey propositional meaning: a word has the same “dictionary” meaning regardless of the way it is said, but there is less general agreement on how many other kinds of meaning can be conveyed. Most lists include attitudinal, pragmatic, grammatical, and discoursal meanings, and it is these that will be examined here.

Attitudinal meaning

We know intuitively that intonation can convey emotions and attitudes, but what is more difficult is to ascertain how this is achieved. We should first distinguish between attitude and emotion: there have been many studies of the effect of emotion on the voice, but the accurate recognition of discrete emotions on the basis of voice alone is unreliable. According to Pittham and Scherer (1993), anger and sadness have the highest rate of identification, while others, e.g., fear, happiness, and disgust, are far less easily recognized. If individual emotions are hard to identify, it suggests that they do not have consistent effects on the voice. However, it does seem to be possible to identify certain dimensions of emotion in the voice, namely whether it is active or passive, or whether it is positive or negative (Cowie et al. 2000). As with emotions, there are similar difficulties with identifying attitudes. There is a plethora of attitudinal labels – all familiar from dialogue in fiction (Yes, he said grumpily; No, she said rather condescendingly…, etc.). Yet experiments (e.g. Crystal 1969), show that listeners fail to ascribe labels to speech samples with more than a minimum of agreement. O’Connor and Arnold (1973) and Pike (1945) attempted for pedagogical reasons to identify the attitudinal meanings of specific melodic patterns, but one only has to change the words of the sample utterance to evoke an entirely different meaning. This suggests that the meaning, however intuitively plausible, does not lie in the melodic pattern itself. According to Ladd (1996), the elements of intonation have very general, fairly abstract meaning, but these meanings are “part of a system with a rich interpretative pragmatics, which gives rise to very specific and often quite vivid nuances in specific contexts” (1996: 39–40). In other words, we need to look to pragmatics, and the inferential process, to explain many of the attitudes that listeners perceive in someone’s “tone of voice”.

Pragmatic meaning

In order to explain some of these pragmatic effects we first need an idea of general, abstract meanings, which, in certain contexts, are capable of generating prosodic implicatures. The most pervasive is the meaning ascribed to final pitch contours: it has been suggested, for example, that a rising tone (L*H) indicates openness (e.g. Cruttenden 1986) or nonfinality (e.g. Wichmann 2000), while falling contours (H*L) indicate closure, or finality. This accounts for the fact that statements generally end low, questions often end high, and also that nonfinal tone groups in a longer utterance also frequently end high, signaling that there is more to come. We see the contribution of the final contour in English question tags; they either assume confirmation, with a falling tone as in: You’ve eaten, haven’t you, or seek information, with a rising tone, as in: You’ve eaten, /haven’t you? The “open”–“closed” distinction also operates in the context of speech acts such as requests: in a corpus-based study of please-requests, of the type ‘Can/could you … please’ (Wichmann 2004), some requests were found to end in a rise, i.e., with a high terminal, and some in a fall, i.e., with a low terminal. The low terminal occurred in contexts where the addressee has no option but to comply and was closer to a polite command, while the rising version, ending high, sounded more tentative or “open” and was closer to a question (consistent with the interrogative form). The appropriateness of each type depends, of course, on the power relationship between the speaker and hearer. If, for example, the speaker’s assumptions were not shared by the addressee, a “command”, however polite, would not be well received and would lead the hearer to infer a negative “attitude”.

The low/high distinction has been said to have an ethological basis – derived from animal signaling where a high pitch is “small” and a low pitch is “big”, and, by extension, powerless and vulnerable or powerful and assertive respectively. This is the basis of the Frequency Code proposed by Ohala (1994) and extended by Gussenhoven (2004), who suggests that these associations have become grammaticalized into the rising contours of questions and the falling contours statements, but also underlie the more general association of low with “authoritative” and high with “unassertive”.

Another contour that has pragmatic potential is the fall-rise, common in British English. It is frequently exploited for pragmatic purposes to imply some kind of reservation, and is referred to by Wells (2006: 27–32) as the “implicational fall-rise”. In the following exchanges there is an unspoken “but” in each reply, which leaves the hearer to infer an unspoken reservation:

Did you like the film?

The /acting was good.

Are you using the car?

/ No

How’s he getting on at school?

He en/joys it.

Information structure

It is not only the choice of tonal contour – i.e., whether rising, falling, or falling-rising – but also its location that conveys important information. The placement of prominence in English conveys the information structure of an utterance, in other words how the information it contains is packaged by the speaker in relation to what the hearer already knows. Nuclear prominence is used to focus on what is new in the utterance and the default position is on the last lexical word of a phrase, or more strictly on the stressed syllable of that word. This default placement is the background against which speakers can use prominence strategically to shift focus from one part of an utterance to another. In most varieties of English, the degree of prominence relates to the degree of salience to be given to the word in which it occurs. If the final lexical item is not given prominence it is being treated as given information or common ground that is already accessible to the hearer, and the new information is signaled by prominence elsewhere in the phrase or utterance. In this way, the hearer can be pointed to different foci, often implying some kind of contrast. In the following exchange, the item “money” is being treated as given, but the word “lend” (probably with an implicational fall-rise) sets up an implied contrast with “give”:

Can you give me some money?

Well, I can lend you some money.

This technique of indicating what is assumed to be given information or common ground is, like other aspects of intonation, a rich source of pragmatic inference.

Grammatical meaning

A further source of intonational meaning is the phrasing or grouping of speech units through the placement of intonation boundaries (IPs, tone-group boundaries). Phrasing indicates a degree of relatedness between the component parts, whether in terms of grammar, e.g., phrase structure, or mental representations (Chafe 1994). The syntax-intonation mapping is less transparent in spontaneous speech, but when written text is read aloud, phrase boundaries tend to coincide with grammatical boundaries, and the way in which young children read aloud gives us some insight into their processing of grammatical structures: when word by word reading (she – was – sitting – in – the – garden) changes to phrase by phrase (she was sitting – in the garden) we know that the reader has understood how words group to become phrases. Phrasing can in some cases have a disambiguating function, as in the difference between ||He washed and fed the dog|| and ||He washed | and fed the dog|| (Gut 2009). However, such ambiguities arise rarely – they are often cited as examples of the grammatical function of intonation, but in practice it is usually context that disambiguates and the role of intonation is minimal. One important point to note is that pauses and phrase boundaries do not necessarily co-occur. In scripted speech, there is a high probability that any pause is likely to co-occur with a boundary, but not that each boundary will be marked by a pause. In spontaneous speech, pauses are an unreliable indicator of phrasing, since they are performance-related.4

Discourse meaning

Texts do not consist of a series of unrelated utterances: they are linked in a variety of ways to create a larger, coherent whole. Macrostructures are signaled inter alia by the use of conjunctions, sentence adverbials, and discourse markers. There are also many typographical features of written texts that guide the reader, including paragraphs, headings, punctuation, capitalization, and font changes, all of which provide visual information that is absent when listening to a text read aloud. In the absence of visual information, readers have to signal text structures prosodically, and to do this they often exploit gradient phenomena including pitch range, tempo, and loudness. Pitch range, for example, is exploited to indicate the rhetorical relationships between successive utterances. “Beginnings”, i.e., new topics or major shifts in a narrative, often coinciding with printed paragraphs, tend to be indicated by an extra-high pitch on the first accented syllable of the new topic (see Wichmann 2000). In scripted speech this is likely to be preceded by a pause, but in spontaneous monologue there may be no intervening pause but a sudden acceleration of speech into the new topic, the so-called “rush-through” (Couper-Kuhlen and Ford 2004: 9; Local and Walker 2004). In conversation this allows a speaker to change to a new topic without losing the floor to another speaker.

If, in contrast, speakers wish to indicate a strong cohesive relationship between two successive utterances, the pitch range at the start of the second utterance is compressed so that the first accented syllable is markedly lower than expected. Expansion and compression of pitch range also play a part in signaling parenthetical sequences. Typically these are lower in pitch and slightly faster than the surrounding speech, but sometimes there is a marked expansion instead; in each case the parenthetical utterance is marked out as “different” from the main text (Dehé and Kavalova 2007). These prosodic strategies for marking macrostructures are also observable in conversational interaction, where they are combined with many more subtle phonetic signals that, in particular, enable the management of interaction in real time. This aspect of discourse prosody is the focus of much work in the CA framework (see Chapter 11 by Szczepek Reed in this volume).

The strategies described above are all related to the structure of the text itself, but there is a recent strand of research into intonational meaning that investigates how the pitch relationships across speaker turns can signal interpersonal meaning, such as degrees of rapport between speakers. This is seen as an example of a widely observed mirroring, or accommodation, between conversational participants. It occurs in many ways – in posture, gesture, accent, and in prosody. Meaning is made not by any inherent characteristics of individual utterances or turns at speaking but by the sequential patterning, in other words, how an utterance relates prosodically to that of another speaker. We know, for example, that the timing of response particles such as mhm, right, ok, etc., is important: if they are rhythmically integrated with the rhythm of the other speaker they are perceived to be supportive, while a disruption of the rhythm is a sign of disaffiliation (Müller 1996). Sequential pitch matching has similarly been found to be a sign of cooperativeness or affiliation: speakers tend to accommodate their pitch register to that of their interlocutor over the course of a conversation (Kousidis et al. 2009) and this engenders, or reflects, rapport between the speakers.5 This can have an important effect on interpersonal relations, as has been observed in a classroom setting (Roth and Tobin 2009): “in classes … where we observe alignment in prosody, participants report feeling a sense of solidarity …”(2009: 808).

In summary, at a very abstract level, the placement and choice of pitch accents and the way in which speech is phrased can convey grammatical and pragmatic meaning, such as speech acts, and also the information structure of an utterance. The phonetic realization of these choices, i.e., exploiting the range of highs and lows that the voice can produce, can convey discourse discontinuities, such as paragraphs or topic shifts, and, conversely, continuities in the cohesive relations between successive utterances. All these choices can also be exploited by speakers to generate pragmatic implicatures, which are often interpreted as speaker “attitudes”. Finally, the whole range of prosodic resources, including pitch, loudness, and timing are drawn on to manage conversational interaction, including ceding and taking turns, competing for turns, and holding the floor, and in the creation or expression of interpersonal rapport.

REFERENCES

- Beckman, M.E. and Pierrehumbert, J.B. 1986. Intonational structure in Japanese and English. Phonology 3(1): 255–309.

- Bing, J.M. 1980. Aspects of English Prosody, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

- Boersma, P. 2001. Praat: a system for doing phonetics by computer. Glot International 5(9/10): 341–345.

- Bradford, B. 1988. Intonation in Context, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brazil, D. 1994. I, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., and Goodwin, J. 2010. Teaching Pronunciation: A Course Book and Reference Guide, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Chafe, W. 1994. Discourse, Consciousness, and Time: The Flow and Displacement of Conscious Experience in Speaking and Writing, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Clark, H.H. 1996. Using language, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Couper-Kuhlen, E. and Ford, C.E. 2004. Sound Patterns in Interaction, Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Cowie, R., Douglas-Cowie, E., Savvidou, S., McMahon, E., Sawey, M., and Schröder, M. 2000. Feeltrace: an instrument for recording perceived emotion in real time. In: Speech and Emotion: Proceedings of the ISCA Workshop, R. Cowie, E. Douglas-Cowie, and M. Schröder (eds.), 19–24, Belfast NI: Textflow.

- Cruttenden, A. 1986. Intonation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cruttenden, A. 1997. Intonation, 2nd edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Crystal, D. 1969. Prosodic Systems and Intonation in English, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dehé, N. and Kavalova, Y. (eds.). 2007. Parentheticals, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Grice, M.(2006. Intonation. In: Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, K. Brown (ed.), 2nd edition, 778–788, Oxford: Elsevier.

- Gussenhoven, C. 2004. The Phonology of Tone and Intonation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gut, U. 2009. Non-native Speech: A Corpus Based Analysis of Phonological and Phonetic Properties of L2 English and German, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Hahn, L.D. 2004. Primary stress and intelligibility: research to motivate the teaching of suprasegmentals. TESOL Quarterly 38(2): 201–223.

- Halliday, M.A.K. 1967. Intonation and Grammar in British English, The Hague: Mouton.

- Kenworthy, J. 1987. Teaching English Pronunciation, New York: Longman.

- Kohler, K. 2006. Paradigms in experimental prosodic analysis: from measurement to function. In: Language, Context and Cognition: Methods in Empirical Prosody Research, S. Sudhoff (ed.), Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Kousidis, S., Dorran, D., McDonnell, C., and Coyle, E. 2009. Time series analysis of acoustic feature convergence in human dialogues. In: Digital Media Centre Conference Papers, Dublin Institute of Technology.

- Ladd, D.R. 1996. Intonational Phonology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ladd, D.R. 2008. Intonational Phonology, 2nd edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Levis, J.M. 1999. Intonation in theory and practice, revisited. TESOL Quarterly 33(1): 37–63.

- Levis, J.M. and Grant, L. 2003. Integrating pronunciation into ESL/EFL classrooms. TESOL Journal 12(2), 13–19.

- Levis, J. and Pickering, L. 2004. Teaching intonation in discourse using speech visualization technology. System 32(4): 505–524.

- Local, J. and Walker, G. 2004. Abrupt joins as a resource for the production of multi-unit, multi-action turns. Journal of Pragmatics 36(8): 1375–1403.

- Mennen, I. 2004. Bi-directional interference in the intonation of Dutch speakers of Greek. Journal of Phonetics 32(4): 543–563.

- Mennen, I. 2007. Phonological and phonetic influences in non-native intonation. In: Non-native Prosody: Phonetic Descriptions and Teaching Practice, J. Trouvain and U. Gut (eds.), 53–76, The Hague, Mouton De Gruyter

- Mennen, I., Schaeffler, F., and Docherty, G. 2012. Cross-language difference in F0 range: a comparative study of English and German. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 131(3): 2249–2260.

- Müller, F. 1996. Affiliating and disaffiliating with continuers: prosodic aspects of recipiency. In: Prosody in Conversation, E. Couper-Kuhlen and M. Selting (eds.), 131–176, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- O’Connor, J.D. and Arnold, G.F. 1973. Intonation of Colloquial English,2nd edition, London: Longman.

- Ohala, J.J. 1994. The frequency code underlies the sound-symbolic use of voice pitch. In: Sound Symbolism, L. Hinton, J. Nichols, and J.J. Ohala (eds.), 325–347, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pickering, L. 2001. The role of tone choice in improving ITA communication in the classroom. TESOL Quarterly 35(2), 233–255.

- Pierrehumbert, J.B. 1980. The phonology and phonetics of English intonation. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Pierrehumbert, J. and Hirschberg, J. 1990. The meaning of intonational contours in the interpretation of discourse. In: Intentions in Communication, P. Cohen, J. Morgan, and M. Pollack (eds.), 271–310, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Pike, K. 1945. The intonation of American English. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Pittham, J. and Scherer, K.R. 1993. Vocal expression and communication of emotion. Handbook of Emotions, New York: Guilford Press.

- Roth, W.-M. Tobin, K. 2010. Solidarity and conflict: prosody as a transactional resource in intra- and intercultural communication involving power differences. Cultural Studies of Science Education 5: 805–847.

- Schmerling, S. 1976. Aspects of English Sentence Stress. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Steele, J. 1775. An Essay Towards Establishing the Melody and Measure of Speech, London: Bowyer & Nichols [Reprinted, Menston, The Scholar Press, 1969].

- Van Bezooijen, R. 1995. Sociocultural aspects of pitch differences between Japanese and Dutch women. Language and Speech 38: 253–265.

- Wells, J. 2006. English Intonation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wennerstrom, A. 1994. Intonational meaning in English discourse: a study of non-native speakers. Applied Linguistics,15(4): 399–420.

- Wennerstrom, A. 1998. Intonation as cohesion in academic discourse. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 20(1): 1–25.

- Wennerstrom, A. 2001. The Music of Everyday Speech: Prosody and Discourse Analysis, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wichmann, A. 2000. Intonation in Text and Discourse, London: Longman.

- Wichmann, A. 2004. The intonation of please-requests. Journal of Pragmatics 36: 1521–1549.

- Wichmann, A., House, J., and Rietveld, T. 2000. Discourse effects on f0 peak timing in English. In: Intonation: Analysis, Modelling and Technology, A. Botinis (ed.), 163–182, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Williams, B. 1996. The formulation of an intonation transcription system for British English. In: Working with Speech, G. Knowles, A. Wichmann, and P. Alderson (eds.), 38–57, London: Longman.