25

The Emergence of ICT-Based Development Strategy in India: An Analysis of Policy and Outcome

M. Rajesh

25.1 Introduction

The Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), and its linkages with the economic development and social transformation, have invited significant academic attention and debates in the recent years, particularly in the emergence of new studies on ‘new economy’ or ‘knowledge-based economy’. As compared to any other conventional productive sectors in the economy, the ICT sector is considered as more knowledge intensive; and ‘knowledge’ is the key factor of production, ‘sidelining both capital and labour’ (Drucker, 1993). The production, diffusion and consumption of the ICT goods and services, will induce the productivity and growth process of an economy (Gordon, 2000; Baily, 2002; OECD, 2003; Basant et al., 2007). This chapter mainly takes up the research on an ICT-based policy initiative that was undertaken by India, and its impact on the economy. Furthermore, it analyses the ICT policies of the major ICT-producing states in India, and their performances in the sector.

This chapter evolves under the conceptual framework of ICT diffusion and development of an economy. In general, the contribution of ICT can be viewed at two different but interrelated levels—ICT production and diffusion. The ICT production refers to the contribution to output, employment and export earning resulting from the production of the ICT goods and services. This is limited to just one segment of the economy, and not related to the spread of ICT among the masses (Kraemer and Dedrick 2001). The ICT diffusion refers to the Information Technology (IT)-induced development, through enhanced productivity, competitiveness, growth and human welfare, resulting from the use and spread of this technology in different sectors of the economy and the society. Many of the studies in these areas are anecdotal citing and are not based on the analysis of hard data. India has attempted to profit from the ICT growth through a series of institutional innovations and export-oriented policy measures, based on the implicit assumption that a market-oriented ICT production strategy will also result in the diffusion of new technology and the ICT-induced development.

The statistical evidence and literature show that the production of ICT and its exports have increased (Arora et al., 2001; Kumar, 2001; Joseph, 2002a and b, 2006; D’Costa, 2004; Parthasarathi and Joseph, 2004). The literature on the diffusion-based development of ICT, which looks beyond the firm level adoption of the ICT and productivity growth, however, is scanty. Though there are some literature on the diffusion-based ICT strategy and its economic impact in the OECD countries, they have not gone beyond a case study methodology, lacking a theoretical framework (Gust and Marquez, 2002; Van Ark and Piatkowski, 2002; OECD 2003; Pilat, 2003).

25.2 The Emergence of ICT-Based Development Strategy

In tune with the policy reforms initiated in India since 1980s, various economic reform measures are being undertaken to integrate the Indian economy with the rest of the world. As part of this reform agenda, the economy has undergone a major change in its development strategy, from import substitution to export orientation. Opening up of the economy further initiated various policy changes, in the different sectors of the economy. The effect of this policy change was reflected in removing the rigid international trade barriers, such as tariffs and quotas, and also in removing the entry barriers to the domestic and foreign private investors.

During this decade, all over the world, there took place a major technological change in the form of ICT production and diffusion. The development literature observes that the production and diffusion of the ICT will induce the competitiveness, economic growth and development in a region. Production of ICT is more knowledge and skill intensive, than any other conventional productive sectors. In this context, India and most of the developing countries adopted their policy initiatives accordingly to enter into ICT production. The ICT-induced economic development, in the developing countries like India, mainly depends on the production of ICT goods and services, and its global trade. The production of ICT goods includes the production of hardware and software goods, and of the ICT-enabled services (ITES). There is a further distinction in terms of knowledge intensity and skill intensity in the ICT production. The production of hardware and software goods is more knowledge intensive, and helps to transform the economy as knowledge-based. On the other hand, the production of ICT-enabled services is more skill intensive, but limited in terms of the knowledge intensity.

India’s comparative advantage in low wage but skilled human resource persuaded the nation to rework its policies to attract global finance in the sector ICT. As a result, at the national level, the government has initiated some reforms to attract the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the Indian economy. Reforms in the banking and financial sector, and in the telecommunication and ICT infrastructure, further induced the growth in the Indian ICT sector. In addition, the central government has directed the states to make its own separate IT policies, to reap the advantages of the emerging ICT revolution.

Pandey et al. (2004) point out that in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, unintentional outcomes of the restrictive governmental policies and pure accidents contributed in shaping India’s ICT future. For example, in the 1970s, the Government of India (GoI) brought in a policy change that required all the foreign companies to lower their equity share to 50 per cent, while operating in India. This forced International Business Machines (IBM) to close down business in India, making the Indian companies less reliant on mainframe computers produced by the IBM. The Indian diaspora in the United States also contributed to the growth of the software industry in India. Indian software professionals in the United States were the mentors of the early Indian software companies, and trained and hired software professionals from India to work in the United States. The difference in the wage rate between India and the United States was the reason for this. While hiring software professionals to work in the United States was more expensive than letting them work in India, it was much cheaper than employing the US professionals. What emerged finally was a mixed business model of offshore outsourcing, whereby some of the software professionals worked in the client’s premises in the United States, while others worked in the companies’ back office in India. Finally, in the 1990s, the Y2K problem proved to be the ultimate jackpot for the Indian firms. The programme which was required to tackle the Y2K problem was COBOL. COBOL was no longer taught in the US universities as it had turned obsolete in the 1990s, but was still taught in India. This proved to be a significant advantage for the Indian IT vendors as Y2K contracts helped them to enter the US market, and build networks and trust. It was, paradoxically, not the cutting-edge technology which came to the help of the Indian software companies and workers, but obsolete but useful technology! Pandey et al. (2004) show that while the governmental policy helps industry, it need not be the end of the story; accidents and technological backwardness do matter. The policy analysis that follows should be read by keeping this caveat in mind.

This chapter examines various policies that were envisaged at the national and the major ICT-producing state levels, to benefit from the ICT production and its overall outcome. The chapter is organized in two sections. The first section highlights the various policies that were formulated in the country over a time period for facilitating the ICT industry. The second section talks about some empirical evidences on the policy impact at the national and regional levels. In addition, specifically, it examines how Kerala’s ICT strategy evolved over a time period, in terms of ICT production and diffusion, and what the outcome was.

25.2.1 The Policy Analysis Framework

This policy analysis has adopted two dimensions of the ICT-based benefits and the regional development—direct benefits and indirect benefits. The direct benefits include the production of the ICT industry, the employment generation and the export earnings. The ICT includes IT and telecommunications. The ICT industry includes IT hardware and software industries; the IT software industry includes IT software, IT service and IT-enabled service. However, it excludes the IT training institutions that provide training to the public at large, and other public interventions taken up by the government for diffusing ICT among the masses. The diffusion component or usage is mainly coming under indirect benefits. The indirect benefits include the economic and social benefits, accrued through the diffusion of ICT that includes but not limited to the increase in efficiency, productivity, competitiveness and growth of the using sectors. Therefore, the policy initiatives are analysed with reference to the above-mentioned dimensions.

25.2.2 Reform-Led ICT Strategy at National Level

This section of enquiry mainly explains how the government’s economic reform intervention, laid the foundation stone to the ICT development in India. The policy frame that affected the IT Industry can be broadly divided into two—one set of policies dealt specifically with the IT industry, while another set of general policies of liberalization that induced the IT industry to grow. India’s quest to explore the emerging opportunities in the sector, ICT persuaded the country to exploit the reform situation, timely and efficiently, in favour of the ICT.

25.2.3 The Evolution of the ICT Industry Policy

The post-independence era of India focused on the search for self-reliance. However the electronics industry was inconsequential, with no domestic production. The computer industry was synonymous to computer hardware, and software was custom-made by trained professionals. The IBM and International Computers Limited (ICL), the two foreign multinationals importing outdated computing machineries to the country, had a complete monopoly over the industry. The Indo-China war and the Indo-Pakistan war during the 1960s brought out the strategic importance of the electronics industry in India. Acting on the Dr Homi Bhabha Committee in 1965, the government directed the foreign companies to initiate indigenous development, since IBM was not ready to relent from its position. In 1977–78, IBM was forced out of operation. ICL reduced its proportion of equity participation and reorganized itself into a new firm, the International Computers India Manufacture (ICIM). Following the recommendations of the Bhabha Committee, the strategic importance of the electronics industry was recognized, Electronics Corporation of India Limited (ECIL) was established for the production of small and medium computers in 1971.

The ECIL was built into a government monopoly by effectively creating institutional barriers to entry for both the private domestic and foreign producers. In 1975 the public sector monopoly enterprise, the Computer Maintenance Corporation (CMC) was established to service all the foreign systems installed in the country. The ECIL became the dominant player in the Indian market, accounting for 40 per cent of the systems (Joseph, 1997). The restrictive policies insulated the industry from interacting with the newer technology in the world market, resulting in widening the technology gap with the rest of the world (Brunner, 1991). Moreover, the domestic demand for mini computers could not be met by the state monopoly. The agency operation of the foreign firms increased. The private domestic firms were to work as agents to the foreign MNCs, thus restricting the growth of the domestic private sector.

However, the importance of the computer software development was recognized by the erstwhile Department of Electronics, as early as in 1972 (Parthasarathy and Joseph, 2004). For the purpose of software exports, duty-free import of computers was permitted during the period. The Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) reached at an agreement in 1974, wherein it was allowed to import hardware in return for the export of software. The foreign-owned software export operations were permitted from the Santa Cruz Export Processing Zone from 1982. The Computer Policy of 1984 initiated the establishment of Software Development Promotion Agency, and the software export-related imports were further liberalized. The 1984 computer policy removed most of the institutional barriers, including the barriers to entry on the MRTP firms and the FERA firms. The MNCs sought India as a software development source, as well as a market for software products.

With the liberalization of the economy in 1991, the entry barriers to foreign participation were removed completely, technology transfer was made open, private participation was encouraged in policy making and risk capital was allowed in the sector. In order to streamline the functioning of the venture capital, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), issued guidelines to which a venture capital fund has to adhere, in order to carry out its activities in India.

In the 1990s, at a national level, the GoI initiated various liberalized policy measures to attract global capital investment, which also had an impact on the ICT industry. The policies were mainly formulated under the dimensions of covering major factors like framing an advanced investment incentive mechanism in the ICT industry, infrastructure development in the ICT industry, strengthening of the foreign investment practices, the strengthening technology transfer properties and the e-governance for efficient functioning of the government. The Department of Information Technology (DIT) has worked out different investment incentive mechanisms, to attract global finance and domestic private investors to make India a front runner in the age of information revolution. The GoI’s early policies, like the National Telecom Policy (NTP) 1994 and 1999, the Internet Service Providers Policy 1998 and India’s entry into the WTO in 1995, etc. further energized the sector. Subsequently, the GoI directed the Indian states to formulate a policy framework for promoting the ICT industry in its own regional development perspective.

A new dedicated ministry was formed for the encouragement of the electronics and IT production and use, within the economy. A national task force on IT was formed, to ensure strategic approach to promotion and growth of the IT industry. The national task force on Human Resource Development for the IT was formed, to promote the generation of the IT-related skills within the economy.

To promote export activities in this sector, the government has taken various measures to provide adequate infrastructure facilities for such industries. As a part of this objective, the Software Technology Parks of India (STPI) was established and registered as an autonomous society, under the Societies Registration Act 1860, of the DIT, Ministry of Communications and Information Technology in 1991. The STPIs eased the implementation of the Software Technology Parks (STP) scheme, for the promotion and development of the software industry and the enhancement of the software exports, by providing infrastructure facilities, including the High Speed Data Communication (HSDC) links. It enabled export-oriented software firms to conduct exports operation, at a pace commensurate with the global standards. Companies in these parks can import goods duty free and for the first five years, without corporate taxes. The parks have centralized computing facilities, and members get complete access to HSDC links and the Internet. The leaders of the park provide the single governmental contact for all the procedures such as licenses, import certificates, etc. allowing the Indian firms to avoid the bureaucracy of the central government. The STPI, as of now, has over 40 centres spread across the country and helping about 6500 software exporting companies.

The technology parks, which provided basic infrastructure and helped in taking advantage of the agglomeration economies, were envisaged through the STPI. The STPs are allowed duty-free imports of capital goods, raw materials, components software, hardware and other related inputs. The STPI centres act as ‘single-window’ in providing services to the software exporters. Some of the STP centres provide incubation infrastructure to the Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), enabling them to commence operations without any delay.

The Information Technology Act (2000) was enacted with an aim to provide legal framework to facilitate electronics commerce and electronics transaction, and aims to recognize the electronic contracts, prevention of computer crimes, electronic filing and documentation, digital signature, etc. The IT act gives the legal framework for these technologies, and raises the electronic records to the level of conventional paper-based physical ones as primary evidence for all the legal requirements.

The role of the state at the policy level as well as in actual production had been substantial in developing this sector. The fruitful state participation, in the production in the formative stages of the industry and later enhancing the private domestic participation through successful policy options, has been pivotal in creating this dynamism within the sector.

25.2.4 The General Policies that Had Impacted on ICT Industry

The policy of reforms followed by the GoI in the post-1991 period recognizes the important role of the foreign capital in the industrial and economic development of the country. The foreign capital inflow is encouraged not only as a source of the financial capital, but also as a facilitator of knowledge and technology transfer. Over the past 15 years, the GoI has undertaken several initiatives and measures to encourage the foreign investment inflows, particularly the flow of the FDI into the country. The deregulation in the banking and financial sectors, opened up the investment opportunities for the private capital and facilitated the entry of the foreign banks into the Indian banking market. As a result, there is an increased competition in the banking sector and the new financial institutions. The deregulation of the interest rates allowed the banks to determine the deposits and lending rates. The prior approval of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for large loans was eliminated, and the sector became more market-oriented. This deregulation increased access to the financial capital for the emerging ICT-based companies, and expanded their market opportunities. The reform that took place in the Indian stock market in 1992 further encouraged the global finance to invest in the booming ICT sector in India. The capital market reforms, in 1993, permitted the Indian firms to list in the foreign stock exchanges and helped them to move globally for capital accumulation. This expanded the worldwide opportunity for the Indian ICT firms tremendously. This initiative helped first generation Indian IT companies like the TCS, Wipro, Infosys and HCL to spread their roots all over the world, and transform as Indian multinational companies.

The government has permitted up to 100 per cent foreign investments in the software sector, to attract FDI through the automatic route. A foreign investor is not required to seek active support of the joint venture partnership, for investing in a new IT-ITES venture in India like some other sectors. Moreover, the FDI policy has been favourably drafted to promote the outbound investments and facilitate global acquisition by the Indian companies. The investment limit for the overseas acquisitions has been increased to 200 per cent of the net worth of the Indian company, as on the date of the last audited balance sheet, without the prior approval from the RBI. Furthermore, to promote growth of the IT sector, the GoI has introduced various relaxations of policies relating to the inbound and outbound investments, exchange control relaxations, incentives for the units located in a Domestic Tariff Area (DTA) or under the Export-Oriented Units (EOU), the STP, the Special Economic Zones (SEZ) and the Electronic Hardware Technology Park (EHTP) schemes.

The development of an efficient and reliable telecom infrastructure is necessary, to sustain the growth of the ICT and ITES industry in India. Moreover, tele-density and Internet penetration are the key growth factors for the domestic software and service industry. The growth of the telecommunication infrastructure is one of the major prerequisites to develop the ICT-based production and diffusion in the country. In this regard, India’s performance was remarkable. The restructuring of the telecommunication sector started in the early 1980s, but most of the liberalization took place after 1994, with the new telecom policy. The Indian telecom sector has witnessed a rapid transformation, since it was deregulated to allow private participation. Over the past decade alone, carefully crafted policy has helped drive a balanced agenda for the sector by influencing a decline in the pricing and increased affordability on one hand, and increasing access penetration and usage on the other, resulting in a strong growth. The annual growth rates in the tele-density over the past two years have been higher than those observed over the 50 years from 1948 to 1998.

The government announced the NTP 1999, with the objective of setting guidelines for the development of a reliable and robust telecom infrastructure in India. In the NTP 1999, the government took initiatives to strengthen the role of the telecom regulator, and separate its police and licensing functions from its role as a service provider. As a part of this policy initiative, it reassigned the service provision from the license fee based models to the revenue sharing models, and opened the Domestic Long Distance (DLD) market to private competition. Further, the GoI liberalized the Internet Service Providing (ISP) sector in 1998. Since then, the number of ISPs has increased to about 190, as of March 2003. The ISPs in India provide a range of services such as dial-up connections, broadband services, Internet telephony, leased line circuits and Internet Private Leased-line Circuits (IPLC). The prominent ISP in India was the public sector company VSNL. Further, the government granted licenses to the Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to set up international gateways in 2000. This ended the VSNL monopoly of being the sole provider of the international bandwidth to India.

The government liberalized the International Long Distance (ILD) sector in 2002. This was two years ahead of the government’s commitment to the WTO to liberalize the telecommunications sector, and remove the trade barriers for the foreign investors. The government allowed Internet telephony in 2002. This has given the consumers a cheaper option for making international calls.

The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) introduced a unified licensing regime from November 2002, which enabled the service providers to offer fixed and mobile services under one license. This increased the competition in the Indian cellular market. The government has commissioned a National Internet Backbone (NIB), covering all the states. The NIB is intended to provide a high bandwidth domestic backbone infrastructure in India. These initiatives have given a boost to the sector.

Figure 25.1: Circle-wise Number of Internet Subscribes in India (as on 31 December 2009)

Source: Department of Telecommunications, Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Government of India.

The Indian telecom sector is dominated by wireless technologies, which include the cellular mobile and the fixed wireless technologies. In fact, almost the entire increases in the availability of telephones have been contributed by the wireless technologies. India has one of the highest ratios of wireless-to-wireline technologies, which is now almost five (Mani, 2005, 2007a and b). The wireless segment consists of two kinds of technologies GSM1 and CDMA.2 The liberalization has proceeded, and today 76 per cent of the mobile (GSM) market share in India is private owned compared to the 9 per cent of the private ownership of the fixed lines. In the CDMA wireless service, 99 per cent is owned by the private sector.

The Indian customers are taking up wireless technology in a big way. They prefer wireless services compared to wireline services. In fact, many customers are returning their wireline phones to their service providers, as the mobile provides a more attractive and competitive solution. The main drivers for this trend are quick service delivery for mobile connections, affordable pricing plans in the form of pre-paid cards and increased purchasing power among the 18–40 years age group, as well as a sizeable middle class.

Figure 25.2: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Telecom Sector in India

Source: Department of Telecommunications, Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Government of India, 2010.

India’s telecommunications sector is now among the most deregulated in the world, and presents the potentially lucrative opportunities for the service providers and the equipment vendors alike. Currently, the Indian telecommunications network with 110.01 million connections is the fifth largest in the world, and the second largest among the emerging economies of Asia (Goyal and Suman, 2006).

As a part of this phenomenal growth in the wireless market, there is an increase in the FDI in this sector. If this trend continues, India can rejuvenate her present telecom equipment manufacturing industry, and compete with the ‘Asian Dragon’ China for a good market share in the global telecom hardware production. This enlarged and highly networked telecom infrastructure, primarily enabled India to reap the emerging advantages of the ICT and helps to transform as a manufacturing hub for the mobile telecom equipments.

25.2.5 Policy Impact on ICT Production and Diffusion in India

The general climate of the ICT as an industry has undergone vast changes, under the proactive modes of state interventions, in terms of creating a conducive policy frame for building an infant industry, and then withdrawing from the scene after the industry gained competitive strength. However, the ICT as a technology for the development and growth had limited success in India, though of late some changes are visible. To begin with, the success story of ICT production is documented below. This is followed by a discussion on the performance of the ICT as a technology in India’s growth and development.

The ICT production in India consists of electronic hardware, software and the ITES. For this analysis, components like computer software and hardware, ITES/BPO (Business Process Outsourcing) and electronic instruments like industrial equipments, medical equipments, office equipments, consumer electronics and telecommunication hardware and related services are taken. All these segments are interdependent and complement each other.

Figure 25.3: ICT Productions in India, 2003–04 to 2008–09 (Rupees in Crore)

Source: Electronics and Computer Software Export Promotion Council, 2010.

Over the last decade, the exports of various ICT components like the electronic hardware, computer software and the IT-enabled services have become a large component of the exports of the country. The production of electronic hardware accounts for 24.93 per cent of total ICT production and the software and the ITES accounts for 75.07 per cent in 2008–09, and registered a growth of 23.93 per cent over the year 2007–08. India’s electronic hardware and computer software/ITES accounts for a share of 19.12 per cent, in India’s overall export during the year 2008–09.

The production of the ICT, estimated at Rs 379754 crore, accounts for a share of 7.70 per cent in India’s GDP at current prices during 2008–09. This is slightly higher than the share of this sector in India’s GDP in 2007–08 estimated at 7.64 per cent. It marked a continuous growth in India’s GDP. India’s total production of the ICT, estimated at US$ 82.57 billion, accounts for a share of 3.13 per cent in the world production of ICT.

The percentage share of India’s ICT export, to the total export, has increased since the post-reform period. During 1995–96 period, the share of India’s IT export to the total export was 3.84 per cent. In 2008–09 it has grown to 19.12 per cent. This shows an increasing trend over the time period.

The production in the Indian ICT industry is mainly dependent on the external market than the domestic market. Since India’s focus was on earning foreign exchange, its policy was biased in favour of the export of ICT goods and services. The initial reason behind it was the low ICT market expansion in India. This is evident in its foreign exchange reserve, and the export-oriented production of the ICT. India’s foreign exchange reserve shows a rapid increasing trend since 1991. During the year 2008–09, out of the total production only 79.92 per cent was exported to various countries of the world and only 20.08 per cent was consumed by the domestic market.

Figure 25.4: Share of ICT Productions in India’s GDP

Source: Electronics and Computer Software Export Promotion Council, 2010.

Figure 25.5: Share of ICT Export in India’s Total Export

Source: Electronics and Computer Software Export Promotion Council, 2010.

During the year 2008–09, India exported its various ICT commodities to 247 countries of the world. This is an increase of 50 countries when compared to 2000–01. North America maintains the top position for India’s export. It accounts for 53.09 per cent of the total ICT exports from India. The export to North America during 2008–09 registered a growth of 24.48 per cent. The export to EU countries, registered a growth of 52.39 per cent during the year 2008–09 over the year 2007–08. Singapore, Hong Kong and other South Asian countries, remains at the third position for India’s export. The export to Japan, Korea and other Far East countries and Middle East countries, also registered a good growth during 2000s.

Figure 25.6: India’s Foreign Exchange Reserve Since 1991

Source: Reserve Bank of India, 2007.

Figure 25.7: Percentage Share of Export to Total ICT Production in India

Source: Electronics and Computer Software Export Promotion Council, 2010.

Figure 25.8: Region-wise Export of Indian ICT Industry During 2008–09

Source: Electronics and Computer Software Export Promotion Council, 2010.

The United States and Europe remain the top two countries for the export of software goods and services from India, and contributed 89 per cent of India’s total software export in 2008–09. North America remains the top destination for India’s export of computer software and services. However, due to the impact of the global financial crisis, there has been a decline of 5 per cent in the percentage share of the computer software and the services exports. Export to the European countries, registered a growth rate of 48.72 per cent during the year 2008–09. The Middle East countries have emerged as third top destination for India’s software and services exports, during the year 2008–09 with a high growth of 198 per cent. However, there has been a slight decline in export to Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, other Far East Countries and Latin America during the year.

The export-oriented ICT strategies, in the last few decades, have thus rewarded the sector with a high growth. However, the almost complete export-oriented growth, catering to the global value chain, on the other hand, kept IT as a technology away from fostering the growth and development processes within India.

Even when India occupies an enviable position among the IT-producing countries, its position in terms of the diffusion of the technology has been very poor (Table 25.1). The Personal Computer (PC) penetration was only 0.89 per 100 inhabitants, compared to 50.8 per 100 inhabitants in Netherlands. The level of penetration was lower than the low income countries like Sri Lanka and China, or the middle income countries such as Mexico. The performance of Internet diffusion was also very similar to that of the PCs. Only 0.7 per cent of the Indian population used Internet, while it was much higher at more than 6 per cent in China. The gap between the developed economies and India, in each of these indicators, was even more conspicuous.

TABLE 25.1 International Comparison of ICT Diffusion

Source: ITU World Communication Indicators 2006.

However, the state had been taking an active role in diffusion of the IT in economy in the recent years. The important contribution of the government strategy in the growth of the ICT is the telecom policies which enabled a low cost computer networking in the country. The digital divide has come down, and access to telephone and Internet has drastically increased. During 2003, 83.3 per cent villages in India achieved direct access with telecom facilities, and the Internet subscribers grew from 4,76,680 in 2000 to 45,49,618 in 2004.

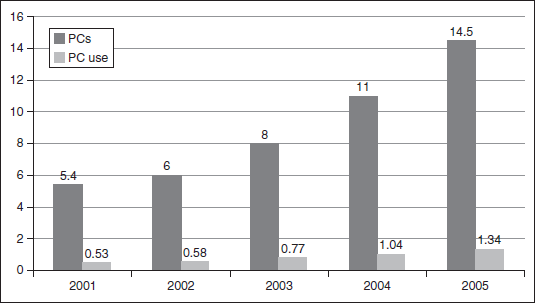

The PCs increased from 5.4 million in 2001 to 14.5 million in 2005. Use of the computer also witnessed a tremendous progress. The use of the ICT has been encouraged by the state, not only through the policy measures but also through direct intervention in various developmental initiatives, such as achieving the goals of the decentralized planning through e-governance, achieving the millennium development goals with the assistance of the IT, rural development and catalysing the rural economy through the IT interventions. Some of the successful government schemes are mentioned below.

The establishment of the National Informatics Centre, and its efforts to connect all the district headquarters, was one of the earliest initiatives towards digitally interconnecting the whole of India.

The National E-Governance Action Plan for 2003–2007 was initiated in 2003. The plan seeks to build the legal, policy-related and the infrastructure requirements, for the long-term growth of e-governance in the country. It has also mooted a number of Mission Mode Projects at the centre, state and integrated-service levels, to create a citizen- and business-centric environment for governance.

The Bhoomi e-governance project is another landmark initiative to digitize the land records of Karnataka, jointly funded by the GoI and the state government of Karnataka. Under this project, more than 20 million land records of 6.7 million landowners in 176 taluks of Karnataka have been computerized.3 AP Online is an e-governance gateway for the government of Andhra Pradesh, in partnership with the TCS, to offer multiple services, through a single window, to its citizens. Similarly, AP Online is comprehensive in scope and over 200 informative, interactive and payment services to the citizens are under development across the state. AP Online is easily accessible through multiple delivery channels, homes and offices, anytime, anywhere. The gateway provides the Information Services, regarding the Andhra Pradesh Government Departments such as, functions of the department, acts and rules, services offered, budget documents, forms and procedures, organizational performance, government orders, etc.

Figure 25.9: Villages in Each State with Direct Access to Telecom Facilities in India

Source: Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

Figure 25.10: Personal Computers (PC) (in Million) and Use per 100 Population in India

Source: Department of Telecommunications, Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Government of India.

A backward district of Madhya Pradesh, one of the poorest states of the country, called Dhar, has been in news since the implementation of the Gyandoot project. The Gyandoot project, launched in 2000, connects the rural district by the Internet and provides vital information for the agrarian sector. The project covers over 600 villages in the entire district.

Realizing the potential of the ICT for welfare and development, a number of initiatives have been mooted at the instance of both the private corporate bodies and the civil society.

Famines and hunger deaths occur mainly due to the hoarding and speculation in the grain market. A large share of the insecurity, related to the food availability is due to asymmetric information flow in the Indian market. The ICTs can be a crucial intermediary in wiping out the distortions in information flow. The accurate and timely information, regarding the areas of food surplus and shortages, can be facilitated through the ICT. The Food Insecurity and Vulnerability Information and Mapping System (FIVIMS) purports to fill up this critical role. The FIVIMS, in conjunction with the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), aims to improve awareness regarding the food security issues. The organization is in operation in many Asian countries, including India.

The Global e-Schools and Communities Initiative (GeSCI) is an international initiative that recognizes the vital role of the ICTs, in educational development. The GeSCI works in partnership with the local ministry of the country, towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) of primary education. The GeSCI also convenes global partners, who can provide expertise, technical, physical and financial support. In India, the GeSCI has identified four states, namely, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan and Karnataka to partner with, create strategies to deliver full-scale low-cost, accessible educational technologies to schools and communities.

One of the path-breaking initiatives was taken up by the Foundation of Occupation Development (FOOD), aimed at promoting entrepreneurship among women using the ICTs. The project titled ‘Intercity Marketing Network for Women Micro-Entrepreneurs’, attempted as a pilot project in Tamil Nadu, is a closed group communication network for the community-based women organizations to promote inter-city direct sales of products made by artisans and skilled workers.

The UNDP and WHO had collaborated to start the Health Internetwork Project, to document and assess the impact of the ICTs on the flow of reliable, timely and relevant information for health services provision, policy making and research. India was chosen as one of the study regions, due to the availability of resources and skills, its public health programme, the range of agencies that provide health services and a growing private sector.

A number of micro-level experiments are underway in different parts of India, aiming to realize the potential of the IT in the rural economy. One of the earliest programmes was the Computerized Rural Information Systems Project (CRISP), wherein the Rural Development Ministry and the NIC collaborated to deploy the ICTs in each district’s rural development agencies with emphasis on the importance of the ICT, especially in social sectors such as health, education and rural development. Some of the ICT initiatives that have gained importance in the last few years are documented below.

The e-choupal is a success story of private participation for the rural development in India. The ITC’s endeavour to use ICT for supply chain management in the agroproducts market for processing, marketing and delivery, has created a win-win situation for both the corporate and the rural populace. While the ITC has gained in terms of efficiency, the rural farmers have gained in terms of higher income. Moreover, the gains from the ICT use have also generated positive spillovers in the economy.

The M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF), established in July 1988, is engaged in the fields of agriculture and rural development, seeking to build an environmentally sustainable and socially equitable rural agrarian base by harnessing science and technology. The pioneering initiative from the MSSRF for the ICT-led rural development in the country is The Jamsetji Tata National Virtual Academy (NVA). The Jamsetji National Virtual Academy for Rural Prosperity is spearheading the movement for Mission 2007—Every Village is a Knowledge Centre through a National Alliance.

Apart from the national level, the corporate and civil society interventions towards developing the ICT as an industry, and the ICT as a development enhancing technology, the states had separate policies and measures in encouraging the IT sector and IT diffusion. Now we turn our attention to this aspect.

25.2.6 ICT Strategy at State Level

According to the central government’s direction to states to make its own separate Information Technology (IT) policies to reap the advantages of the emerging ICT revolution, in the late 1990s, the states have adopted various policy measures for their regional development. Most of the states have prepared policies accordingly, to complement or facilitate the Central government’s strategy. As a part of this, most of the state governments in India have announced special promotional schemes, offering various packages of incentives and procedural waivers for the IT sector. These schemes focus on the key issues of infrastructure, electronic governance and the IT education, and provide a facilitating environment for increasing the IT proliferation in the respective states. While these are state-specific initiatives, there is a fair degree of uniformity across the states, as newer locations have modelled their schemes on those offered in states that have successfully nurtured a thriving IT industry.

The National Association of Software and Service Companies (NASSCOM), an independent trade body which promotes growth and facilitates trade and business in the software sector, both nationally and internationally, states that the state governments have mainly facilitated the central policy, and introduced various incentive packages for the industry. Some of the incentive packages are mentioned below.

- A majority of the states have either promulgated a government order or a notification permitting all the establishments in the respective jurisdictions, engaged in the IT-enabled services (including call centres), to work on national holidays, allow women to work in night shifts and offices to function 24 hours a day, all through the year.

- The state governments have announced the IT policies that seek to create—through focused Human Resources Development (HRD) programmes—a trained pool of manpower, with the skills and aptitudes appropriate for the ITES industry requirements.

- The state governments have introduced the IT Industry Employment Promotion Scheme, as a direct incentive for both the government and the industry.

- Most states in India have STP and SEZ schemes, offering world class infrastructure with reliable data communication facilities. Further, to leverage private sector investments, the state governments have proactively come out with several special incentives.

- The industrial power tariff and all the other admissible incentives and concessions applicable to the industries, in respect of power, have been extended to the IT industry by certain states.

- The IT software industry is exempted from the zoning regulations, for the purposes of location in certain states.

- In principle, self-certification and exemption, as far as possible for the IT industry, from the provisions of certain acts and regulations have been permitted by certain states.

In this regard, southern states are the early birds; Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala prepared various policies and implemented them at the right time of opportunity. As an outcome of their early initiatives, they are being assessed as premier states, which are using the ICT effectively.

According to the E-Readiness Assessment Report, the e-readiness4 of the states reveals that the southern states, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, have remained leaders over the three-year period, while the northern states of Chandigarh, Haryana and Rajasthan have shown vast improvements. Apart from these, Sikkim from the north-eastern region has done exceedingly well.

The ICT infrastructure and the ability to use it are clearly strongly dispersed across the Indian states. Some states in India, such as Andhra Pradesh, have made notable strides in using the ICTs for their development. Among the leaders, Tamil Nadu has improved its e-readiness in the past year by consciously working on the environment, especially involving the private sector in the development of ICT infrastructure and introducing the ICTs in state-level policies. Kerala has used the competitive advantages of the state (high proportion of literacy and awareness of citizens) and concentrated in the usage segment. Among the aspiring leaders, Gujarat has tried to replicate its success in industry segments, such as petrochemicals and chemicals, in the ICT sector. Among the expectant category, Madhya Pradesh’s ascent is notable, and is largely due to the private sector involvement in the developmental activities (e.g., in e-Choupal). In all cases, these Indian states have made progress due to leadership, connectivity, availability of skilled manpower, increased private sector development and creation of institutional mechanisms with sustainable impact.

However, in terms of the production of the ICT and foreign exchange earnings through its export, the ICT industry in India is clustered in a few locations of the country, even in states. The major production centres are concentrated in the southern region of India, and contribute 62 per cent of the export earning to India. The northern region contributes 15 per cent and the western and the eastern regions provide 20 and 3 per cents, respectively.

Figure 25.11: E-Readiness of Indian States

Source: E-Readiness Assessment Report, 2004, Department of Information Technology, Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Government of India.

Figure 25.12: Regional Share of IT Production and Export, 2008–09

Source: Electronics and Computer Software Export Promotion Council, 2010.

Apart from the regional difference, it can be observed that there is a wide disparity among states in a particular region. In the case of southern region, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh are the most favourable locations for the ICT-based companies. Karnataka with 31 per cent remains the highest exporter of computer software and the ITES from India, during the year 2008–09. The second largest contributor is with 20 per cent, and Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh’s contribution 18 and 13 per cent, respectively, during 2008–09.

In the northern region, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh have almost equal share in the total export; 6 per cent each during 2008–09. Delhi stands in third position in the northern region, with overall share of 2 per cent to the total export from India. The other major contributors are Rajasthan, Chandigarh and Punjab with 0.30, 0.30 and 0.17 per cent, respectively. Considering the eastern and western region, West Bengal (2.20), Orrisa (0.47) and Maharashtra (19.53) are the major players.

In terms of export of the ICT, even if western and northern States are not early birds in framing the ICT-oriented development strategy, it shows a good leapfrog advantage in its ICT production and export. Until 2006–07 the major share of IT production, especially the software production and the services, was polarized in the southern part of India.

In short, India’s strategy in ICT is mainly focused on the export of software goods and services, and it has made a significant contribution to the economy. In the post-reform regime, the economy has witnessed growth and development through the growth of ICT. However, a regional disparity in the production of ICT is high, and the industry is clustered in a few locations of the nation.

The aforementioned policy review, at the national level, shows that the early boom in the ICT industry influenced the country to frame policies in the direction of reaping the ‘direct advantages’ of the ICT industry. Perhaps these policy initiatives have tempted the ICT industry to concentrate on the advantageous geographical locations, especially in the urban areas. It does not mean that the government had ignored backward or rural regions and spread of the ICT. But it has given priority to the ‘direct benefit’ kind.

Figure 25.13: State-wise Share of Export of ICT in 2008–09 (%)

Source: Electronics and Computer Software Export Promotion Council, 2010.

25.2.7 A Case Study on Kerala’s ICT Strategy

As compared to the other Indian States, Kerala is one of the first states that introduced various ICT policies to reap the early advantages of the ICT-based economic development. Kerala’s remarkable achievements in the Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI) and other human development indicators showed that it was a highly potential Indian state to become a production hub of the ICT. However, the facts and figures show that even if Kerala has taken various peculiar initiatives to promote the ICT production in the state, it cannot make any relevant presence in terms of the ICT production and its export. To understand and analyse this paradox, we have taken a case study on Kerala’s ICT policies.

The government of Kerala has taken a number of initiatives for exploring the emerging opportunities in the ICT, since the early 1970s. As a beginning, the state has achieved a unique position among the state governments in the country, by formulating a policy on science and technology in 1977. Among other significant statements, the policy spelt out the intention to develop ‘research institutions which will maintain a higher standard of activity and intellectual integrity, and pay the highest consideration to the pursuit of knowledge, and its applications to human welfare as a worthwhile endeavour’ in it. As part of this initiative, the state has established various institutions in science and technology sector. The establishment of Kerala State Electronics Development Corporation (KELTRON) and its subsidiary Electronic Research and Development (ER&DC) are the major steps in this regard. Keltron is the first state level electronics development corporation in India. It was the major company in India, which engaged in producing telecommunication products. The ER&DC was involved in developing the embedded software for the domestic market (Joseph, 1999). In the early 1990s, there were two major institutional interventions to promote growth of the software industry in the state. The first one was the setting up of a software technology park (STPT) in Trivandrum at the instance of the Department of Electronics. This was in tune with the STP scheme, initiated at the national level. As a continuation to this, a Techno Park was set up by government of Kerala. It was aimed at providing infrastructural support for electronics research, design, development, manufacturing and training ventures, as well as for the software development units. In 1970s, the state’s approach regarding Keltron and its subsidiaries was to enter directly into production as an investor. But in the case of the STPT and the Techno Park, the state changed its approach after the lessons learnt from its previous experience, and opened them to private individuals to participate in the investment and production. The fear of technological change made the trade unions in Kerala to resist the inflow of the external capital. They were afraid that the mechanization process would reduce the job opportunity in the state. The foreign investors were, hence, hesitant to invest in these ventures. By the time, the neighbouring states like Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh had started exploring the emerging opportunities. As a remittance-based economy, until early 2000s, the major investors in the IT industry in Kerala were the Non-resident Keralites (NRKs). Even now, most of the major companies in Trivandrum Techno Park are set up by the NRKs and are domestically grown.

25.2.8 Kerala’s Strategy Towards ICT Production

During the late 1990s and in 2000s, in the boom of the ICT production, especially, the software goods and IT-enabled services, the state of Kerala has formulated and reformulated its information technology policy several times, unlike its neighbouring states. It initiated its first IT policy in 1998. Subsequently it revised the policies in 2001 and 2007. Most of the southern states are early starters in framing policies for the ICT industry. Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh come under this group. The early starters were the states that now have a significant, well-established ICT industry, and were able to attract the investments both from India and abroad. The e-readiness index which measures the capacity of a state to participate in the networked economy in relation to the country at large also is favourable to these states. The early starters have shown a stronger performance in terms of the general economic growth and several other development indicators, as compared to the late starters. This pattern, however, does not apply uniformly. A state in the early-starter category may still be a moderate performer in the ICT production. For instance, the performance of Kerala in the ICT-induced regional development, in terms of ‘the direct benefits’ has not been as good as its neighbouring states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. The difference also reflects in Kerala’s policy priorities.

Among the early starters, Karnataka remains the highest exporter of computer software and the ITES from India. Karnataka has contributed, on an average, 35 per cent of the total export for last three years. The second largest contributor is the state of Maharashtra, which accounts for a share of 18 per cent of the total export in this sector during 2003–04 to 2008–09. The third, fourth and fifth positions are held by Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Haryana, with an average share of 15, 13 and 8 per cent, respectively. However, the early starter Kerala’s performance in this regard is only 0.75 per cent.

The major ICT-producing neighbouring states of Kerala have prepared their policies according to the national policy priorities, and given preference to ‘direct benefits’ like ICT goods, services export and employment generation. They have framed their policy, giving more emphasis to attracting the global finance into their ICT sector. The IT policies of the different states have many elements in common. But in Kerala’s case, it shows a slightly different picture.

In essence, the state-level IT policies have focused mainly on the initiatives like the promotion of private investment, the incentive schemes for taxation and finance, the investment in physical infrastructure relating to IT such as land and real estate development, power and water, roads and air transport, telecommunication and Internet connectivity, and the industrial parks in the private and the public sectors; also, investment in the human resources development, including research, education, training and diffusion of the IT applications.

Kerala’s neighbouring states, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh focused on developing high-end education, building infrastructure facilities and attracting multinational investors. States such as Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu have explicit and comprehensive IT polices with a strong commitment to implementation. The interesting thing to observe is that, thus far, state IT policies have focused on the urban dimensions. Although the rural dimension has been accepted as very important, in terms of an economic and development rationale, it is not the primary focus in resource allocation. The private sector investments tend to focus on the urban clusters in the states, due to its spatial comparative advantage, whereas little or no resources are diverted to the rural and backward areas.

While preparing Kerala’s ICT policy, the policy makers expected to take advantage of the state’s past achievements in the physical quality of life index, through the information revolution, and convert Kerala as a knowledge-based society. Since the initial period, the state attempted to strike a balance between ‘the direct benefits’ as well as ‘the indirect ones’. At that time, it was a new approach of prioritizing the diffusion, unlike its neighbouring states. Also, it is expected that the high rate of diffusion of the ICT in different sectors of the economy will enhance the efficiency and productivity, especially, in the primary and secondary sectors which were lagging behind. Moreover, the rationale behind this policy was the enhancement of efficiency in the already growing service sector. At the same time, like any other states in India, Kerala has improved its infrastructure and implemented various measures to attract private investors. Its STP in Thiruvananthapuram is one of the first initiatives in India of this kind. As a continuation of the infrastructural development, the state has taken further steps in building the IT infrastructure, like Infopark, Kochi and Smart City project. Kerala’s investment incentive mechanism is mainly governed by considerations of the domestic employment generation and the spatial distribution of the ICT industry. However, the investment incentive mechanism of the neighbouring states is highly based on the volume of investment, rather than employment generation and spatial distribution.

In the first IT policy in 1998, Kerala has given low priority for attracting global finance in the IT industry, due to its conventional rigidity and past development wisdom. It is quite visible in its investment picture that involvement of the NRKs mooted the foreign investment in Kerala. According to the State Economic Review (2005), 37 per cent of turnover in the Techno Park companies are from the NRKs companies. It is only a recent phenomenon that the Indian multinational companies, like Infosys, TCS and WIPRO have started their full-fledged working infrastructure in Kerala. As compared to their roots in the neighbouring states, they are in a primitive stage in Kerala. Even now, there is no big multinational establishment in Kerala’s IT sector, except for some service-level companies like the Allianz Conrnhill, Ernst & Young, Mickinsey & Co., etc.

Recently, Kerala has withdrawn its attitudes against the global capital in the ICT, and formulated some incentive mechanism to accelerate the levels of investment inflows, including the foreign capital into the hardware, software and ITES sectors. By then, the neighbouring states have adopted separate policies to reap the advantages, out of one of the leading export revenue generation sector in the IT industry—ITES and BPO.

Kerala’s first IT policy shows that the state has given preference to the diffusion and dissemination of IT. The reasons for prioritizing diffusion over production, were—high literacy and phenomenal growth in education, health and other services; ease of geographical access in the extent and stretch, both longitudinal and lateral; the large migrant population with extensive demands for connectivity; the extensive telecom network reaching all towns and villages; availability of the educated youth; the export-based trade and commerce; and potential for the tourism industry. Therefore, the state expected that all these peculiarities would turn out advantageous to its transformation, as knowledge-based economy. Moreover, it has given preference to the domestic investors than the foreign capital, to protect its prevailing traditional labour interests.

Kerala is the first region in the world that introduced new policy initiatives to promote and diffuse Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) technology among the masses. The second policy document announced the government’s wishes to encourage the judicious use of the FOSS that complements and supplements the proprietary software, to reduce the total cost of ownership of the IT applications and solutions, without compromising on the immediate and medium term value provided by the application. The state promoted research in the use of the FOSS, in the context of education, governance and for general use at home, to make IT truly a part of the daily lives of the people of the state. The state also encouraged projects, such as Simputer that is low cost, based on open software and attuned to the needs of the common man. Kerala’s recent policy document, in 2007, further reaffirms its commitment to the FOSS and its diffusion among the masses.

Kerala State IT mission is the nodal agency to coordinate and implement various mass IT programmes in the state. It consists of a team of professionals, from the industry and the government. Its primary responsibilities include enhancing the IT industry base, the ICT dissemination, implementing e-governance initiatives and developing human resources. The ICT can improve efficiency and transparency in the working of the government, including the local self-government. The state focused on the maximum use of ICT in governance, to provide the best possible services to the citizen (Table 25.2). The state has gone a long way in respect of the ICT initiatives in e-governance. It has been selected as the second best state in India in e-governance implementation, for the year 2005. The state has developed various ICT-based e-governance tele-centres, like FRIENDS and community-based IT experiment ‘Akshaya’, aiming at development of the core sectors like agriculture and industry, and social sectors like health and education.

The state’s latest policy has given high priority and incentive to spread the diffusion- based ICT project ‘Akshaya’ for experiment all over Kerala. The policy document outlines that the state aims to replicate the success of Akshaya in the entire state, and will integrate and disseminate the major development activities of the government through Akshaya. Further it puts emphasis on Kerala’s social concern and the digitally inclusive growth. The policy document 2007 is titled as ‘towards an inclusive knowledge society’.

In short, Kerala’s strategy in the ICT industry reveals that as compared to the IT-producing neighbouring states, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, Kerala has adopted an ICT strategy giving more priority to the use and spread of ICT among the masses with social equity. In other words, it followed a strategy on the basis of ‘indirect benefit’ dimension of the ICT. This imbalance was reflected in Kerala’s ‘direct benefits’—the ICT production, the direct employment generation and the export earnings, even though it has much potential and is an early starter in framing the ICT policies. However, at present, Kerala’s move towards further enhancement of the infrastructure availability, technical human resource creation, institutional modernization and private investment-induced growth strategy shows the symptom of reaping the ‘direct benefits’ of the ICT industry as well. Moreover, it expects that its past efforts in creating a knowledge-intensive community, through various initiatives like Akshaya, will be an added advantage; and the state can achieve a good position in the global knowledge-intensive economy in a sustainable manner.

TABLE 25.2 Kerala’s Investment in E-Governance, 2005

| E-governance initiatives | Spread | Investment (in crore) |

|---|---|---|

| FRIENDS | 14 district head quarters | 4.50 |

| Department computerization | 11 government departments | 200.00 |

| Secretariat Wide Area Network (WAN) | government secretariat | 0.80 |

Source: Government of Kerala, State Economic Review, 2005.

25.3 Summary

This chapter focused mainly on the emergence of a major technological change, in the form of ICT and its impact on the Indian economy. It analyses various policies that were envisaged at the national and the state levels, to benefit from the ICT production and its overall outcome.

In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, the unintentional outcomes of the restrictive governmental policies and pure technological accidents contributed in shaping India’s ICT future. However, this windfall gains have been properly used by the GoI, during the postreform regime. The economic reforms have built a strong base for the ICT production and diffusion in India. Reforms which took place in banking and finance, telecom and ICT infrastructure fuelled the growth of the Indian ICT sector. As an outcome of the policy, the empirical evidence shows that India’s strategy on the ICT is mainly focused on the export of the software goods and services, and it has made a significant contribution to the economy. In the post-reform regime, the economy has witnessed growth and development, through the growth of the ICT. However, regional disparity in the production of ICT is high, and the industry is clustered in a few locations of the nation.

Kerala is one of the early starters in framing the ICT strategies, to explore the advantages of the emerging ICT sector. Its initiatives in establishing the science and technology institutions to promote electronic production and research are well acclaimed all over the India. Even though Kerala has comparative advantage in the human resources, infrastructure and technological background, its initial fear of global capital slowed down the growth of its share in the ICT production and export. However, at the same time, Kerala, as compared to the IT-producing neighbouring states Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, has adopted an ICT strategy giving more priority to the use and spread of ICT among the masses, and an inclusive growth process. In other words, it followed a strategy on the basis of ‘the indirect benefit’ dimension of the ICT. It has adopted this strategy, because it thought that its past achievements in the human development will help the region to transform as knowledge-based economy, if it gives more emphasis on diffusion of the technology. This imbalance between the ICT production and diffusion is reflected in Kerala’s economy in terms of direct employment generation and export earnings. However, at present, Kerala’s move towards further enhancement of the infrastructure availability, technical human resource creation, institutional modernization and private investment-induced growth strategy signals to the potential to reap the ‘direct benefits’ of the ICT industry as well. Moreover, it expects that its past efforts in creating knowledgeintensive community through various initiatives in the e-governance and diffusion-based programmes like ‘Akshaya’ will provide a comparative advantage, and the state can achieve a good position in the global knowledge-intensive economy.

References

Ahluwalia, M. S. (2002). Economic reforms in India since 1991: Has gradualism worked? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(1), 67–88.

Arora, A., and Athreye, S. (2002). The software industry and India’s Economic development. Information Economics and Policy, 14, 25–273.

Arora, A., Arunachalam, V. S., Asundi, J., and Ronald, F. (2001). The Indian software services industry. Research Policy, 30(3), 1267–87.

Arunachalam, S. (1999). Information and knowledge in the age of electronic communication: a developing country perspective. Journal of Information Science, 25(6), 465–476.

Baily, M. N. (2002) “The New Economy: Post Mortem or Second Wind”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 16. No. 2. pp. 3–22.

Basant, R., Simon, C., Harrison, R., and Menezes-Filho. N. (2007). IT adoption and productivity in developing countries: New firm level evidence from Brazil and India. IBMEC Working Paper—WPE-23–2007.

Bowonder, B., Kelkar, V., Satish, N. G., and Racherla, J. K. (2006). Innovation in India: Recent trends. TMTC (Tata Management Training Center) Research Paper. Pune, India.

Bresnahan, T., Brynjolfsson, E. and Hitt, L. (2002). Information technology, workplace organization and the demand for skilled labour. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 339–76.

Brunner, H. P. (1991). Small-scale Industry in India: The Case of the Computer Industry. Small Business Economics, 3: 121–9.

Carlsson, B., and Jacobsson, S. (1997). Diversity creation and technological systems: A technology policy perspective. In C. Edquist (Ed.), Systems of innovation: Technologies, institutions and organization. London: Pinter.

Carlsson, B. (2004). The digital economy: What is new and what is not? Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 15(3), 241–380.

Chandrasekhar, C. P. (2006). The political economy of it-driven outsourcing in political economy and information capitalism. In G. Parayil (Ed.), India: Digital divide, development divide & equity. England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Corcoran, E. (2006). Back-office charity: An Indian outsourcer is outsourcing his business—and helping the rural poor. Forbes, 24 July.

CSIR (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research). (2004). Making technology work for rural India: A step towards rural transformation. New Delhi. http://www.csir.res.in/csir/External/June 2008

Dahlman, C., and Utz, A. (2005). India and the knowledge economy: Leveraging strengths and opportunities. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

Danielsson, J., and Persson, J. (2006). Explaining the success of the Indian IT industry. Department of Economics Lund University. http://www.essays.se/essay/94cf02472c/

Das Gupta, S. (2006). How IT is changing rural India. http://in.redifficom/cms/print.jsp?docpath=/money/2006/apr/07spec.htm.

D’Costa, A. (2002). “Export Growth and Path Dependence: The Locking in of Innovations in the Software Industry”. Science, Technology and Society, Vol. 7, No. 1.

Department of Information Technology. (2004). E-readiness assessment report 2004 for states and union territories. mit.gov.in/download/eready/Forewardcontents.PDF

Dirk, P. (2003). ICT and economic growth: Evidence from OECD countries, industries and firms. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris, France.

Drucker, P. F. (1993). Post-capitalist society. New York: Harper Business.

Economic Review. (2007). Kerala State Planning Board, Government of Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram.

Freeman, C. (1987). Technology policy and economic performance: Lessons from Japan. London: Pinter.

George, K. K. (1993). Limits to Kerala model of development. Monograph Series. Centre for Development Studies. Thiruvananthapuram.

Gordon, R. J. (2000). Does the ‘new economy’ measure up to the great inventions of the past? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14, 49–74.

Goyal, V. and Suman, P. (2006). The Indian telecom industry. IIM, Calcutta: Consulting Club.

Heeks, R. (1996). India’s software industry state policy, liberalization and industrial development. New Delhi: Sage Publications India Pvt. Ltd.

Indjikian, R., and Siegel, D. S. (2005). The impact of investment in IT on economic performance: Implications for developing countries. World Development, 33(5), 681–700.

Jhunjhunwala, A., Ramachandran, A., and Ramachander, S. (2006). Connecting rural India: Taking a step back for two forward. Information Technology in Developing Countries, 16(1). http://www.is-watch.net/node/306

Joeng, K., Huh Oh, J. and Shin, I. (2001). The economic impact of information and communication technology in Korea. In M. Pohjola (Ed.), Information technology, productivity, and economic growth. New York, NY: UNU/WIDER Studies in Development Economics, Oxford University Press.

Jorgenson, D. W., Stiroh. (1999). Information technology and growth. American Economic Review, 89(2).

Joseph, K. J. (1997). Industry under Economic Liberalisation: The case of Indian Electronics. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Joseph, K. J. (2002a). Harnessing ICT for development: Need for a national policy. Information Technology in Developing Countries, 11(3), 109–115.

Joseph, K. J. (2002b). Growth of IT and IT for development: Realities of the myths of the Indian experience. Discussion paper No. 2002/78, Helsinki: UNU/WIDER.

Joseph, K. J., and Abraham, V. (2005). Moving up or lagging behind in technology? Evidence from an estimated index of technological competence of India’s IT sector. In A. Saith and Vijayabhaskar (Eds.), ITs and Indian economic development: Economy, work, regulation. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Joseph, K. J. (2006). Information technology, innovation system and trade regime in developing countries: India and the ASEAN. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Joseph, K. J., and Harilal, K. N. (2001). Structure and growth of India’s IT exports: Implications of an export-oriented growth strategy. Economic and Political Weekly, 36(34), 3263–70.

Kraemer, K. L., and Dedrick, J. (2001). Information technology and economic development: Results and policy implications of cross-country studies. In M. Pohjola (Ed.), Information technology,productivity and economic growth. UK: Oxford University Press.

Krishnan, R. T., and Prabhu, N. G. (2004). Software product development in India: Lessons from six cases. In A. P. D’Costa and E. Sridharan (Eds.), India in the global software industry: Innovation, firm strategies and development. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kumar, R. (2004). e-Choupals: A study on the financial sustainability of village Internet centers in rural Madhya Pradesh. Information Technology for Development, 2(1), 45–73.

Kumar, N. (2001). ‘Indian software industry development: international and national perspective’. Economic and Political Weekly. 36(45):4278–4290.

Kuriyan, R. Ray, I., and Toyama, K. (2006). Integrating social development and financial sustainability: The challenges of rural kiosks in Kerala. 1st International Conference on ICT and Development, UC Berkeley. http://research.microsoft.com/research/tem/kiosks/ICTD2006%20Kerala%20Kiosks%20Kuriyan.pdf

Madon, S., and Kiran, G. (2003). Information technology for citizen—government interface: A study of FRIENDS project in Kerala’. World Bank Global Knowledge Sharing Program. World Bank.

Madon, S. (2004a). Evaluating the developmental impact of e-governance initiatives: An exploratory framework. The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, 1(13), 1–13.

Madon, S. (2004b). Akshaya media launch: Publicity at the right time. Information Technology in Developing Countries, 14(2).

Mani, S. (2005). The dragon vs. the elephant comparative analysis of innovation capability in the telecommunication equipment industry. WP 373, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram.

Mani, S. (2007a). Revolution in India’s telecommunications industry. Economic and Political Weekly, 42(7), 578–580.

Mani, S. (2007b). The growth performance of India’s telecommunications services industry, 1991–2006: Can it lead to the emergence ofa domestic manufacturing hub? Working Paper 390. Centre for Development Studies. Thiruvananthapuram.

Manoj, P. K., and Sudeep, S. (2008). Information and communication technology for economic development: The case of Kerala economy. In M. M. Bai (Ed.), Kerala economy: Slumber to performance. New Delhi: Serial Publications.

Mashelkar, R A. (2001). The Indian innovation system. Development outreach. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Mohanan, P. (2004). Akshaya at a glance. Information Technology in Developing Countries, 14(1).

OECD. 2003. ICT and economic growth—evidence for oecd countries, industries and firms. Paris: OECD.

Pal, J. (2006). Examining e-literacy using telecenters as public spending: The case of Akshaya. http://www.icsi.berkeley.edu/pubs/bcis/akshaya-ICTD.pdf

Pandey, A. Aggarwal, A. Devane, R., and Kuznetsov, Y. (2004). India’s transformation to knowledge-based economy-evolving role of the Indian diaspora. http://info.worldbank.org/etools/docs/library/152386/abhishek.pdf.

Parthasarathi, A., and Joseph, K. J. (2004). Innovation under export orientation. D’Costa, A. P. and Sridharan E. (Eds.), India in the global software industry innovation, firm strategies and development. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Roman, R. (2003). Diffusion of innovations as a theoretical framework for telecenters. Information Technology for Development, 1(2), 53–66.

Schumpeter, J. (1926). The theory of economic development. Cambridge, MA: Harward University Press.

Schware, R. (1987). Software industry in the third world:policy guidelines,institutional options and constraints. World Development, 15(10/11), 1249–1267.

Singh, N. (2002). Information technology as an engine of broad-based growth in India. In P. Banerjee and F. J. Richter (Eds.), The Information Economy in India (pp. 24–57). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sreekumar, T. T. (2002). Civil society and the state-led initiatives in ICTs: The case of Kerala. Information Technology in Developing Countries, 12(3).

Thomas, J. J. (2006). Informational development in rural areas: Some evidence from Andhra Pradesh and Kerala. In G. Parayil (Ed.), Political economy and information capitalism in India: digital divide, development divide and equity (pp. 109–132). Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

UNDP. (1990). The Human development report 1990: Definition and measurement of human development. Paris: Economica.

Van Ark, B., and Piatkowski, M. (2002). Productivity, innovation and ICT in old and new Europe. International Economics and Economic Policy, 1(3), 215–246.

Website: indiastat.com (2010).

Wong, P. K. (2001). The contribution of information technology to the rapid economic growth in Singapore. In M. Pohjola (Ed.), Information Technology, Productivity, and Economic Growth. UNU/ WIDER Studies in Development Economics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.