29

Healthcare Financing in India During the Post-Reform Period

D. Varatharajan and S. K. Godwin

29.1 Introduction: Setting the Tone

In the history of the global economic development, the 1990s had been a period of cataclysmic change not only in terms of the principles governing operations of the government, but also in terms of the philosophy of the change as well. The efficiency of the economic system to be given priority over equity considerations and the former is expected to take care of the latter in the long run. The slow demise of Keynesian economics and the revival of the Classical and Neo-Classical orthodoxy were the conceptual foundations of the economic changes we witnessed since the mid-1980s till today. India could be currently in the midst of the third wave of economic reform. The first wave coincided with the independence when the country inherited an economy with negative or zero economic growth. It laid the economic foundation for independent India through the Five Year Plans and state-led industrialization. The second wave occurred in the mid-to-late 1960s when the agricultural growth slowed down and the country relied heavily on imports for its food requirements. The Green Revolution was launched and hybrid varieties were introduced to enhance agricultural productivity and reduce import dependence. The nationalization of banks was a radical development during this phase when the majority of the rural areas were connected with the banking sector. The third wave, initiated in 1991, is a revisit of the classical laissez-faire paradigm and is seen as a driving force to achieve higher economic growth and stability through free markets across national/international boundaries and minimum government interventions. It is not enough to say that the size of the ‘state’ is changing, but the nature itself. However, a late realization that ‘growth’ itself cannot take care of ‘all’ led to concerns about ‘inclusive growth’ (despite an absence of what it means), especially during the late 1990s. The Millennium Development Goals are a reflection of the inclusive growth concerns at the global level as the targets set by the nostalgic Alma Atta of ‘Health for All by 2000’ remained an enigma.

The health sector could not be immune to waves of change; rather the transition in the economic policy had immediate and in-depth repercussions on the life and death of people. Health sector reforms have been undertaken with more vigour than before as reflected in the policy changes beginning with health financing, especially insurance mechanisms, provision of healthcare, drugs control and pricing, technology transfer. It is argued that efficiency invaded roughly through the territory of the health sector as equity arguments need not always guarantee equity in health outcomes. As an individual’s health status is predominantly determined by activities other than healthcare, so is true for the health sector as well where industrial policies, drug policies, export—import policies and financial policies, have a larger stake than hospitals or health personnel.

This chapter provides an analysis of the Indian healthcare scenario during the postreform period. This chapter has five sections and five subsections. The following section describes the Indian economic reform and its vision, while the next section brings out the healthcare context in India. This section has two subsections. The first subsection elaborates the achievements of the Indian health sector and the returns on the healthcare investment made during independent India. The second one places India on the global map and highlights the gaps in its achievements vis-à-vis the global best. The third section is about the possible impact of the economic reform on healthcare, whereas the following one analyses the performance of the economy after the introduction of reform. The fourth section deals with the implications of reform for health. This section has two subsections—the commercialization of health and urban-rural disparity. The final section is the concluding section.

A brief discussion on the interlinkages between the economic growth and healthcare development could be a starting point for us to penetrate more into the dynamics of the sector.

29.1.1 Growth-Health Linkage

The ultimate aim of the present wave of reform in India is to translate the gains in the economic growth into human well-being, as faster and stable growth of the economy facilitates greater availability of resources for sectors such as health and education. Evidence shows that wealthy nations/individuals are healthy too. A simple scatter diagram of the GDP per capita and life expectancy at birth in 70 countries brings out that the life expectancy increases with the GDP per capita sharply at lower levels of per capita GDP and stabilizes at about US $10,000 (Figure 29.1).

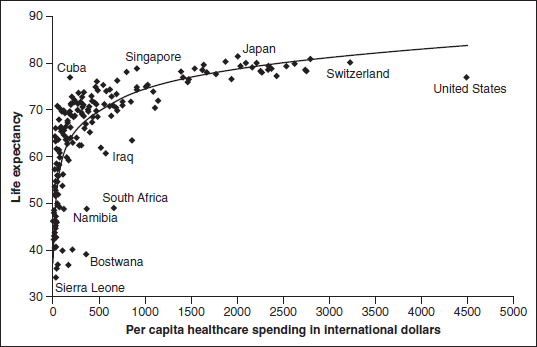

The growth in the GDP results in better overall standard and quality of life resulting from higher literacy, nutrition intake, sanitation and infrastructure, and low dependency ratio. Growth is also expected to bring with it newer opportunities, technologies and products, thus enlarging the choice of and access to healthcare. Moreover, rich countries spend higher proportion of their GDP on health (WHO, 2004) and higher health expenditure is translated into higher longevity (Figure 29.2). Also, the government share in health spending is found to be high in countries where the per capita GDP is high and the health outcome is good where the government share of health expenditure is high.

Optimistic goals apart, the link between the GDP and health is neither exclusive nor uniform as growth does not get automatically translated into health and longevity. As it can be seen from Table 29.1, some countries with high per capita GDP achieved poor health outcome. Botswana, for instance, has a per capita GDP of US $2,980, but countries with similar per capita GDP have attained a life expectancy of 72.5 years as against 61 years in Botswana. Hence, the effect of the economic growth on health has been found to be relatively weak because the economic growth also brings with it the scope for health inequity. The growth in reality provides unprecedented opportunities to the rich to treat even the most cosmetic defects, while millions of poor have no or little access to medical care. Growth, while creating greater opportunities for healthcare, may also open the door for hitherto unknown diseases through unhealthy life styles and environmental damage. Moreover, higher economic growth may trigger higher private spending on healthcare even while boosting the public expenditure. The increased private spending need not necessarily be met entirely from an increased private disposable income and may require considerable debt to fill the gap, especially if the healthcare cost grows faster than the private disposable income.

Figure 29.1: GDP per-capita (in US $) and Life Expectancy (70 Countries) (World Health Organization, 2004; World Bank, 2004)

Figure 29.2: Healthcare Spending and Life Expectancy

TABLE 29.1 High Income and Poor Health (WHO, 2004; World Bank, 2004)

Hence, the improvement of income is clearly an option for, not the sum total of, the development in healthcare.

29.2 Reform and the Vision

India’s present reform had two parts—stabilization and structural reform (Rangarajan, 1998). Stabilization polices were intended to correct lapses and put the house in order, while structural policies were intended to accelerate the economic growth. The major thrust was towards creating a more competitive environment in the economy as the means to improving the productivity and efficiency of the system. The trade policy sought to improve international competitiveness. In order to improve the public sector efficiency, the public sector was made to compete with the private sector, and areas earlier reserved exclusively for the public sector were allowed to the private sector. The reform also advocated that the public sector must withdraw from the areas where no public purpose is served by its presence. The principle of market economy became the main operative principle for all public sector enterprises, unless the commodities and services produced and distributed are specifically for protecting the poorest in the society.

Since the initiation of the reform, there has been a significant change in the opinion regarding the roles of the government and the market. Perhaps, the dominant opinion seems to have moved away from ‘market failure’, reasoning in favour of the government intervention in healthcare, to ‘government failure’, reasoning in favour of the market intervention. The age-long ‘state versus market’ debate is no more, at least among the policy makers in the economic administration.

Now, the reform is about two decades old. From a nation of widespread famine and depending perennially on foreign aid to feed her population in the 1960s, India has progressed to a self-sufficient nation in food production within a short-span of about three decades. The GDP registered a higher growth of 7.2 per cent in 2009–10 despite the global financial meltdown compared to 2.8 per cent achieved during the Third Five Year Plan period (Government of India, 2008). It is projected to grow at around the same rate (8.5 per cent to 9.0 per cent) over the next 15 years (CII-McKinsey, 2002). It is also hoped that India will become one of the top-five countries in the world in terms of GDP by 2020. Growth acceleration is a goal the government considers essential to reduce poverty significantly (10 percentage points by 2012) as per the targets envisaged in the Eleventh Five Year Plan (Government of India, 2008). If this happens, India would be healthier, better educated and more prosperous by 2020. The reform seems to have helped the states too to accelerate their economic growth; from a low level of 0.8–1.2 per cent in the 1960s and 1970s, the per capita state domestic products grew at a healthy rate of 5.5 per cent in the last decades beginning with the 1990s (Government of India, 2008).

29.3 Healthcare Context

Established in 279–236 BC, the Indian healthcare system has a long history. The Indian Ayurvedic system is one of the earliest attempts to conceptualize the science of health and to utilize rational methods of diagnosing illnesses. Western medicine was introduced during the 18 th century, essentially to treat British soldiers. Despite long history, the organized healthcare sector was confined to cities during the pre-Independence period.

On the question of health and well-being, immediately after Independence, the national planners committed themselves to develop the country and its people through a socialist framework, and health had to be an obvious component in it. The post-Independent plans and policies on healthcare were much influenced by visionaries like Joseph Bhore whose Committee on Health and Development in India made the primary care approach the bedrock of the Indian healthcare system, and the public sector was visualized keeping this health system approach in mind. The committee laid down the principle that access to primary care is a basic right and ability to pay or any other socio-economic considerations should not be barriers to accessing care. As a result, a rural-centric, population-based, government-dominant healthcare system was in the offing. The establishment of primary healthcare centres, subcentres and community health centres continued till the 1980s when the first National Health Policy was pronounced. As a result of the continuous efforts, the crude death rate declined from 42.6 per 1,000 population in 1901 to 8 per 1,0 population in 2008, while the Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) came down from 129 per 1,000 live births in 1970 to 52 in 2008 (Government of India, 2008). Consequently, life expectancy at birth increased from 23.8 years in 1901 to 64 years in 2008. However, the achievements are not so significant when we look through a comparative lens. The perceived needs and demands have been undergoing tremendous changes and the resources needed to finance them are greater than ever before. For a state that promised universal healthcare through the public healthcare delivery system, India has allocated only a meager fraction of the public resources for healthcare. The country’s healthcare system evolved with ambitious plans; however, the resources were not adequate to fulfill even the minimum commitments made in the initial plans. The more worrying aspect is that, rather than heavily increasing the public health resources, it came down substantially in successive plans. Though designated as a core social service, policies in the healthcare financing have undergone widespread changes with a major focus on the commercialization of healthcare.

29.3.1 Return on Investment

Despite the phenomenal success, especially during the post-Independence period, India still lags behind many countries that are comparable in terms of the economic status. India’s life expectancy in 2001 falls short of the average for the developing countries, while the IMR is 14 above the average (CII-McKinsey, 2002). The total disease burden in the country measured in terms of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALY) too is high (274 per 1,0 population) compared to the average burden (255 per 1,000 population) among the developing countries. India also does not get sufficient return from health investment, though it spends relatively large share (4.0 per cent) of the GDP on health (WHO, 2004; Government of India, 2008). Even those countries spending less have higher life expectancy (Table 29.2). For instance, Thailand spends 3.7 per cent of its GDP but has a life expectancy 6 years higher than India’s.

The poor rate of return could be attributable to the inefficiency of the system in controlling and managing the resources. The major difference between other Asian countries and India lies in the composition of healthcare resources—private resources dominate the Indian healthcare scene, whereas the government accounts for the maximum in other countries. Private households in India contribute 66.4 per cent to the national health expenditure and account for over 80 per cent of the total primary care spending. National and state governments in India are one of the poorest spenders in the world (Figure 29.3). Poor government spending is reflected in poor health outcomes. Life expectancy follows government spending though the rate of increase in life expectancy is slower than the rate of increase in the government share of health spending.

TABLE 29.2 Countries Spending Less on Health but Having Higher Life Expectancy (2008) (WHO, 2004; Government of India, 2008)

Source: WHO (2010) World Health Statistics 2010.

Figure 29.3: Per-capita Total and Government Health Spending in Some Low-income Countries

Source: Durairaj and Evans (2010).

29.3.2 Scope for Improvement

India has a considerable distance to travel to catch up with the best in the world. As shown in Table 29.3, nearly 100 per cent improvement is possible in the reduction of the IMR, under-five mortality, Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR), and malaria and TB deaths. By preventing infant, child, maternal, malaria and TB deaths, India can hope to enhance its life expectancy by 29.7 per cent. However, it is easy said than done, especially when India has some distance to travel even to catch up with other developing nations. If India desires to catch up with the best, it needs to improve the health system indicators first. First, India’s health expenditure is well below the best and even below the average (Table 29.4). Secondly, the government share in the total health expenditure, as it has been discussed already, lags behind many countries; in fact, India ranks among the bottom-five nations. Thirdly, the private healthcare spending is almost entirely unorganized. Fourthly, the proportion of births attended by skilled personnel is low.

TABLE 29.3 Basic Health Indicators—Comparison with the Best (2008)

Source: WHO (2010) World Health Statistics 2010.

TABLE 29.4 Some Key Health System Indicators in India (2007)

Source: WHO (2010) World Health Statistics 2010.

29.4 Link Between Economic Reform and Healthcare

Economic reform is expected to have close linkages with health outcomes through its impact on health risks (global public goods), healthcare system, the level and distribution of household income and other sectors closely related to the healthcare sector (WHO, 2001). The spread of communicable diseases such as malaria, TB, AIDS and food-borne diseases illustrates the direct effect of an increased international travel (more than two million people cross-international borders every day). Reform could also result in increased environmental and occupational hazards. Steep increase in transnationalization of markets and promotion of harmful commodities such as tobacco are other important components of public health threats. The urbanization or greater mobility and the migration of people from rural to urban areas could result in the use of uncleaned water, improper waste management, inadequate housing, unhealthy lifestyles and overprescription of drugs. As a result, epidemics of non-communicable diseases and injuries are becoming more prevalent.

The trade in health services is likely to grow with rapid increase in trade liberalization as well as the increasing use of technological advances. This could facilitate access to higher level of healthcare services by the better off but neglecting the poor. For instance, the access to innovations such as telemedicine is restricted to the educated rich section of the population. Similarly, R&D efforts may be directed towards solving the problems of the rich with the comparative neglect of poor. The reform also provides insurers and providers with the means to engineer favourable risk pools to maximize their profits. Thus, the reform conflicts with the principles of the universal coverage of healthcare and shared risk upheld by the tax-funded health system (Price, Pollock and Shaoul, 1999). The result is the ‘medical poverty trap’ with more and more people likely to remain untreated (Hillary, 2002).

At the same time, the reform also brings unprecedented opportunities to achieve better healthcare through health system development by enhancing availability, access, utilization, quality of care and affordability. It can happen through various routes such as budget, trade, privatization (user fee, private insurance, promoting private sector, etc.) or decentralization (or autonomy), health knowledge, health promotion, prevention, case management, health system performance and international mobility of health services (Than and Rim, 2001).

The spirit of the reform in India is to translate the economic gains to human development through sectors such as healthcare and education through increased resource allocation. The pre-conditions, however, were an improved performance of the economy and efficient functioning of the government. The country quickly realized, based on our own experience and from the experience of the East-Asian miracle (and subsequent collapse), that the trade-based growth-oriented strategy is not sustainable in the long run, unless we strengthen our asset base because globalization, by design, brought with it extraordinary risks in the form of growing inequality, marginalization and social explosions. This realization brought the two-legged (growth with development) approach into focus and forced the inclusion of ‘human face’ into the reform agenda. The success of this two-legged approach is yet to be ascertained. However, the initial trend is not encouraging because it seems to have only partially succeeded in accelerating the human development prospects.

The Indian approach towards healthcare from the beginning has been residual in nature. The health sector has been a mere absorber of the reform process initiated from elsewhere rather than effecting its own. Reform exercise is no exception and the reform was thrust on the health sector from outside the sector and to a considerable extent from outside the country. The Indian health sector accepted the reform without resistance basically due to the impatient middle class and the private sector (Qadeer, 2000). Nevertheless, the real impact of the reform on healthcare per se is not clearly known yet. Although the growth of the human development index has decelerated a bit from 2.6 per cent per annum during the 1980s to 2.4 per cent per annum during the 1990s, no strong signal has emerged to suggest that the reform has negatively influenced the human development or health. However, indirect signals are now emerging to suggest that human health will indeed get affected in the years to come. For instance, resource flow to health steadily declined during the 1990s from 6.1 per cent of GDP in 1991 to 5.2 per cent in 2008 (Government of India, 2002). Although the decline has been steady since 1970, it was more pronounced during the 1990s (Duggal, Nandraj and Vadair, 1995). The government share in the total healthcare expenditure in the country has come down from about 25 per cent in the early 1990s to 20.1 per cent in 2001; the government health expenditure now hovers around 1 per cent (estimates differ between 0.6 per cent and 1.2 per cent) of the GDP. The healthcare share in the central budget remained static at 1.3 per cent, while the states’ budgetary share of healthcare has come down from 7 per cent to 5.5 per cent. The healthcare share in the plan allocation too slipped down from 1.8 per cent in early 1990s to 1.3 per cent in 2002. The trend in the plan allocation to healthcare indicates that the rate of increase has not matched even with the rate of population growth (Panchamukhi, 2000). The financial allocation for the health sector over the past decade indicates that the public expenditures on health through the central and state governments, as a percentage of the total government expenditure, have declined from 3.12 per cent in 1992–93 to 2.99 per cent in 2003–04. Similarly, the combined expenditure on health as a percentage of the GDP has also marginally declined from 1.01 per cent of the GDP in 1992–93 to 0. 99 per cent in 2003–04. In nominal terms, the per capita public health expenditure increased from Rs 89 in 1993–94 to Rs 214 in 2003–04, which in real terms is Rs 122 (Government of India, 2005).

The distribution of the financial burden of treatment between public and private spending reflects a trend of gradually declining public financing and increasing household expenditure on healthcare. Since reduced public financing in healthcare is related to structural adjustment programmes, the financing space was ‘accommodated’ by private households. For example, in rural India, the healthcare expenditure as a per cent of the total household consumption expenditure increased from 5.43 in 1993–94 to 6.09 in 1999–2000 and 6.61 in 2004–05.

As a per cent of the total, the household consumption expenditure increased from 4.6 in 1993–94 to 5.03 in 1999–2000 to 5.19 in 2004–05 (Government of India, 2005). Table 29.5 is reproduced here to provide an understanding of the fact that the household commitment in the form of out-of-pocket payments has exceeded all definitions of catastrophic spending in all major states in India pointing to the inescapable conclusion of worsening healthcare inequity. Increased share of healthcare spending by households is implied at a number of points. First, the fact that the increase in household health spending is pronounced in rural areas than in urban areas raises concerns of inequity in access to and fairness in healthcare financing. Secondly, even poor households are willing to spend more for healthcare due to the attached increased value of healthcare. Thirdly, due to the decline in the capital expenditure by governments and supplies running out, there is reduction in the quality of public health services. Fourthly, with increased use of higherend technologies, healthcare has become costlier. Finally, as a consequence of increased user charges in public healthcare institutions, individuals are forced to pay more for healthcare. NSSO Rounds also revealed that the poor is spending relatively more on health (Nayantara, Puttaswamaiah and Mishra, 2003). Juxtaposed is the faster growth of the need for healthcare resources in the country on account of higher morbidity, about 10 times higher medical care inflation (it could be more because precise estimates are not available) than the general inflation, the emergence of new and expensive diseases, and discovery and import of newer technologies. This has widened the gap between what is needed and what is possible.

TABLE 29.5 Sources of Healthcare Spending in India, 2004–05 (in Rupees)

Source: Report of National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, Government of India, 2005.

29.4.1 Commercialization of Healthcare

The Indian healthcare sector has grown in terms of commercial importance since the 1990s. The background behind the commercialization seems to be the failure of the traditional commercial sectors to yield the required profit. Since the profitability in other commercial sectors has come down over a period of time, the developed nations started focusing on the service sector such as healthcare that is being seen as a sector with great profit potential. The healthcare sector has been declared an ‘industry’ by the Union Government, and like any other business with profit as the central objective. The liberalization of imports of medical equipments and concessions offered boosted the corporatization project. The private initiatives include an increasing investment by non-resident Indians in the hospital industry, a spurt in corporatization in the states of their original domicile and increasing participation by multinationals keen to explore the health insurance market in India. (Baru, 2000; Purohit, 2001). Public-private partnerships in healthcare have become the rule of the day in recent years. Surveys of the health infrastructure suggest that there is a greater trend towards the concentration of healthcare facilities and corporatization of the healthcare industry with a focus on high profit-margin, superspeciality care. Advanced countries like the US see huge commercial opportunities in the entire spectrum of healthcare and social care facilities, including hospitals, outpatient facilities, clinics and nursing homes. (Pollock and Shaoul, 1889–92; Price, 1999). Moreover, profits of the healthcare industry in the advanced economies started falling due to the market saturation. As a result, healthcare firms withdraw from selected markets and try to capture new markets elsewhere abroad. The strategy also suited the reform process initiated by international institutions such as the World Bank. The expansion of the nongovernment sector depends on the opening of markets in the traditional areas of public provision and the public sector is left to bear the risk for more vulnerable populations but with diminished risk pooling to finance care.

The medical care in India was handed over to the private sector without any mechanism to ensure the quality and price of treatment as well as access to services. Not only were the secondary and tertiary healthcare sectors deprived of resources, but inevitably the primary healthcare sector also suffered. As the cutbacks involved the entire social sector, there was an additional loss of intersectoral support. The cutbacks also affected the functioning of the monitoring units. External funding of the health sector influenced the functioning and autonomy of the national institutions. At the same time, private investment (through public-private partnerships) and user fee in the public sector failed to make any positive impact on the efficiency of service provision and the range of services offered, particularly to the poor. In fact, by increasing the cost of healthcare, they made it more difficult to access public sector services for those who need help the most.

The reduction in the list of drugs under the price control from 378 to 73 only compounded the problems since the drug prices have rocketed. Consequently, the monetary value of the pharmaceutical production has gone up by Rs 130 billion during the last decade, whereas the increase was a mere Rs 38 million during the preceding four decades (Duggal, 2002). Of course, increase in the value of pharmaceutical production need not indicate an increase in the availability of drugs and medicines in the country. It could simply be a value transfer from the consumers to the producers. The prices of drugs that have gone out of price controls since 1995 have already increased significantly by about 77–457 per cent during 1995–98. (Kumar and Pradhan, 2003) Patent regimes also will affect drug prices adversely as it has already happened in China. Welfare losses from the introduction of product patents were estimated to the tune of US $2.9–14.4 billion in six developing countries: Argentina, Brazil, India, Mexico, Korea and Taiwan; the welfare loss to India alone could be in the range of US $1.4–4.2 billion.

29.4.2 Urban-Rural Disparity

The healthcare sector has changed during the last two decades; the private sector has become the major provider of both inpatient and outpatient care. (Government of India, 1998) The decline in the utilization of public healthcare services is mainly a function of the decline in the public health investment during the same period. The utilization of the private sector has not been restricted to upper and middle classes alone, but is used by even poorer classes (Dilip, 2002). Studies have shown that the non-availability of public healthcare services is forcing the poor to seek care from the private sector, even if they are interested in seeking healthcare from the public sector. (Dilip and Duggal 2003). A recent analysis shows disturbing details regarding the Indian public healthcare expenditure in the 1980s and 1990s. For example, the share of the healthcare expenditure in the major states shows a significant fall in the proportion of the healthcare expenditure to total government expenditure—from 6–7 per cent in the 1980s to just over 5 per cent in the 1990s (Selvaraju, A. 2003). In real per capita terms, there has been a positive change in the public expenditure, but the distribution of resources among primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare is not in conformity with the intentions of the national policies with the rate of growth of allocation for primary and secondary care being lower than that for the tertiary care. In many states, the growth in the healthcare expenditure was fully absorbed by salary, leaving little for financing development activities, maintenance, drugs and other consumables. Such a situation is very unwelcome with regard to the quality of healthcare, user satisfaction and utilization, performance, etc. The privatization of healthcare could result in reduced access to healthcare among poorer sections, poorer regions and poorer states in India. The period of decline in the investment in the public health infrastructure in the 1980s and 1990s has witnessed a steady increase in the private sector (Narayana, 2001). This is taking place in the form of expansion of existing facilities and setting up of new ones, investment in buildings, equipment and diagnostic facilities, plush surroundings, etc. (ibid). While there has been a steady quantitative expansion in the number of facilities at least till the mid-1980s, the evidence of quality deterioration is widespread. The health centres crying for repair, non-availability and accessibility of physicians and supporting staff, random supply of medicines, inconvenient timings and absence of privacy are standing testimony to the earlier statement.

Besides, there appears to be disguised unemployment of healthcare resources in the health sector (Varatharajan, Sadanandan, Thankappan, and Nair, 2002). The inefficiency of the public healthcare sector actually affects the rural people and the poor who are found to utilize the public sector healthcare more (Krishnan, 1994). When all the justification— low human development and higher healthcare needs—exists for the location of public facilities in rural areas, hospitals, dispensaries and health centres are actually located in urban areas. About 70 per cent of government hospitals function in urban areas where only 27.8 per cent of India’s population lives. Similarly, only 25 per cent of public and 35 per cent of private hospitals and 10 per cent of public and 30 per cent of private hospital beds are located in rural areas. Urban areas also have 20 times higher bed density and 10 times higher doctor density than the rural areas (Shariff, 1999; UNFPA, 1997). The interstate variation in the doctor and bed availability is, respectively, 6 and 100 times. Kerala is the only state where about 60 per cent of the hospital beds are located in rural areas. States with higher density of medical institutions are found to have an urban bias and a larger proportion of hospitals in total (Shariff, 1999). Also, states reporting higher density of hospital beds have high proportion of beds in the private sector.

As a result of urban-rural differences in the availability of healthcare services, rural people end up spending much larger proportion (estimates vary between 5–15 per cent) of their income on health than their urban counterparts (2.3 per cent). This results in considerable increase in rural poverty. Rural areas are found to have 9.6 per cent more people below the poverty line. Not only that, but also the percentage of deaths that received medical attention has come down to 16.5 per cent during this period from 16.8 per cent. Rural deliveries receiving medical attention has also declined from 18 per cent in 1992 to 17.4 per cent in 1995. The general increase in the healthcare demand coupled with the inability of the public hospitals to provide adequate medical facilities accelerated the growth of the private health sector in India. The demand-supply gap for public healthcare delivery is large and on the rise, and this gap is increasingly being bridged by private healthcare institutions. The general increase in the income levels and the corporatization of healthcare in urban areas have led to the commoditization of healthcare, access to which is determined by the ability to pay for the service. The urban healthcare industry is booming, with a host of private hospitals offering state-of-the-art services for the rich and the middle class. The availability of advanced medical technologies has led to significant rise in the demand for the use of advanced technology. The changes in the disease pattern due to the epidemiological transition, easy availability of financial resources and easing of import restrictions have contributed significantly to the rapid influx of medical technology. The private provision brings a great amount of fresh problems including the non-involvement in the prevention of diseases, overcharging, induced demand, absence of a genuine quality assurance mechanism, etc. The private sector is so heterogeneous that it ranges from large corporate hospitals to small five-bed nursing homes and solo practitioners with questionable qualifications to practitioners who have medical degrees in indigenous medical systems and also practise modern medicine and run diagnostic centres offering numerous services. Various studies have identified that a vast majority of private healthcare providers in urban areas do not follow any norms with regard to either the use of physical infrastructure (space per bed, provision of certain utilities, etc.) or the structural aspects of healthcare (medical and paramedical personnel employed, services offered, etc.). The important problems citied by these studies are lack of physical standards, inadequate spacing of hospitals (a majority of nursing homes are substandard, most of them being housed in tiny flatlets), absence of trained personnel, especially qualified nurses, maternity homes without labour rooms, poorly lit and dirty wards and beds, absence of records of notifiable diseases, births and deaths, etc. (Nandraj and Duggal, 1997; Muraleedharan, 1999). This has also led to the medically unjustified use of technology and the existence of a complex network of arrangements between the physicians in the government sector, the private hospitals and local diagnostic centres. These types of mutual arrangements have a definite bearing on the cost of healthcare since most payments are made out of pocket on a fee-for-service basis. The complexity of actors and their actions, and the structure and conduct of the business make it extremely difficult to frame policies on regulating the private healthcare services. Even in areas where the private provision seems to be theoretically harmless, issues arising out of the inequality in information between the agent (provider) and the principal (patient), uncertainty in incidence and outcomes of treatment, usually work against the consumer. In such chaotic markets, users/consumers are helpless and the competition by itself is a poor efficiency-enhancing device, especially when the consumer is unable to judge the level of quality (Dreze and Sen, 2002).

29.4.3 Some Positive Developments

Despite certain negative aspects, there are some positive developments since 2005. Noticeable among them are the National Rural and Urban Health Missions and the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY). The launching of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) represents a broad change in the Indian healthcare landscape in more ways than one. Primarily, it was meant to undertake an ‘architectural correction’ in the healthcare system and introduced innovations in Indian healthcare by expanding the resource availability, human resource management and decentralizing the healthcare decision-making apparatus. It was meant not only to enhance the equity of the healthcare delivery systems, but also to focus on the efficiency in terms of health outcomes as well. The NRHM is the largest primary healthcare programme being run in any single country. The RSBY is a participatory national health insurance scheme co-funded by the national and state governments and beneficiaries with healthcare services being provided by both the public and private sectors. The progress of the scheme so far has been fast with over 19.4 million smart cards being issued by mid-September 2010. However, its impact on the healthcare access, equity and financial risk protection will be known only after people start utilizing healthcare services (WHO, 2010). Although early experience indicates that less than 1 per cent of the beneficiaries really received healthcare and less than 5 per cent of the collected premiums was used for healthcare, it is too early to pass a judgement on this scheme. The scheme design and its initial enrolment progress has already brought it under the global attention. The hope remains that the scheme would strengthen the transitory process towards universal coverage, the theme for the forthcoming World Health Report.

29.5 Conclusions

The Indian economic reform aimed at improvement in the health of Indian population through increased resources brought in by higher growth of the GDP and saved resources through higher efficiency of the government sector. The policy seems to have failed to achieve this objective if we go by the trend during the 1990s. Neither government nor private resources increased to justify this policy. While the economic growth remained static even after the initiation of the new economic policy when globalization was actively pursued, the share of healthcare in government expenditure has actually come down. There does not seem to have been any improvement in the government sector efficiency either, as the fiscal deficit remained more or less the same during the reform period. Only positive outcome of the reform is the decline in the rate of inflation from a double-digit level in 1990–91 to 4.6 per cent in 2003–04. The medical care inflation during this period, however, remained high. Public agencies including the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in the country find that prices of healthcare and education have gone up significantly (partly attributable to improved quality) even while prices of certain services like telecommunications have declined considerably (RBI, 2010). Hence, the real effect of this low inflation on the private healthcare expenditure or healthcare outcome is not known.

On the other hand, the healthcare sector seems to be moving towards a market regime. The private healthcare sector is increasingly commanding more and more resources, while the government is silently withdrawing from the health sector. There appears to be a ‘government failure’ behind the transition of healthcare sector towards a market regime. Therefore, the basic question arises now as to whether the health sector is best rooted in the market competition or in the government planning. The healthcare sector consists of close to a dozen markets, including the market for health financing (insurance, medical savings account), physician services, hospital services, medical labour, medical education, pharmaceutical, medical equipment and supply. These markets are linked and closely interact with each other. During the past three decades, empirical studies found that there were serious market failures (or absence of prerequisite conditions for a workable competitive market) in the health sector.

Most of these failures are caused by the presence of externalities, asymmetry of information and moral hazards, which exist in a high degree in the various markets in the healthcare sector. In healthcare service provision markets, we would not expect competition to work when patients suffer from life-threatening or critical medical problems. Moreover, the asymmetry of information gives medical professionals strong monopolistic power to set prices and induce demand. In the supply of medical professionals, high barriers of entry have been erected by the government and by the medical profession to assure patients’ safety by restricting the provision of services to those who meet certain standards. This is again mainly due to the asymmetry of information between the patient and the health professionals. In the pharmaceutical and medical device markets, patent laws give monopoly to new drugs and new medical technologies in order to encourage R&D. While these barriers of entry and monopolies were established for good social and economic reasons, none the less, they impair the competitiveness and efficient operations of their markets.

Beyond the state—market dichotomy, other effects of globalization such as increase in health risks, pharmaceutical pricing, drug availability and induced poverty are not yet clear, as some states are slow in adopting the reform. Moreover, there is a lag period for realizing the indirect effects of the reform. Panchayats too have provided another dimension to the healthcare sector after the mid-1990s, but their role in countering the ill-effects of the reform is not clear too. Some states are yet to transfer healthcare to the panchayats as panchayats are yet to be formed. Some other states such as Karnataka have transferred healthcare to panchayats, but only at the district level, while Kerala has transferred healthcare at the village panchayat level. Even in states like Kerala the role of panchayats with respect to the private healthcare sector is unclear.

The role of the private sector in healthcare is another area still left as a conjecture. This is all the more relevant, as the reform has taken the market route in the healthcare sector. In the absence of the government defining its role, the private sector assumes that its role lies in the provision of high-tech curative services. The talks of private-public partnerships are also centred on the hospital sector, once again highlighting and extending the already existing urban bias in the planning and resource allocation within the healthcare sector. At the same time, the urban poor continue to suffer due to lack of primary care and purchasing power.

Certain new schemes have brought more government money into healthcare and with it some hope for an equitable health system in India. If these schemes are sustained and benefits are realized, there is some possibility to move towards universal coverage.

References

Baru, R. V. (2000). Privatization and Corporatisation. Seminar2000. 489.

Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) and McKinsey (a consulting group) (2002). Healthcare in India: The Road Ahead. New Delhi: Confederation of Indian Industry and McKinsey & Company.

Dilip, T. R. (2002). Understanding Levels of Morbidity and Hospitalisation in Kerala, India. Bulletin of World Health Organisation 80(9): 746–51.

Dilip, T. R., Duggal, R. (2002). Incidence of Non-Fatal Health Outcomes and Debt in Urban India Draft Paper Prepared for Urban Research Symposium, 9–11 December 2002, Washington DC: The World Bank.

Dreze, J. and Sen, A. K. (2002). India: Development and Participation. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Duggal, R. (2002) Health planning in India. In: India Health—A reference document. Kottayam: Rashtra Deepika Ltd, 43–56.

Duggal, R., Nandraj, S., Vadair, A. (1995). Health expenditure across states (Part I & II). Economic and Political Weekly 30: 834–44 & 901–908.

Government of India. (Various years). Five Year Plans 1951–2007. New Delhi: Planning Commission.

Government of India. (1998). Morbidity and Treatment of Ailments, 52nd Round, 1995–96. New Delhi: NSSO, New Delhi.

Government of India. (2002). National Health Policy 2002. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

Government of India. (2005). Report of the National Commission on Macro Economics and Health. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

Government of India. (2008). Eleventh Five Year Plan 2002–07. New Delhi: Planning Commission.

Government of India (2008). Eleventh Five Year Plan 2002–07. New Delhi: Planning Commission.

Hilary, J. (2002). The Impact of Trade in Health Services on Equity. Jakarta: ASEAN Workshop on GATS and Its Impact on Health Services; 26–28th March.

Krishnan, T. N. (1994). Access and the Burden of Treatment: An Inter-comparison. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies, UNDP Research Project, Studies on Human Development in India. Discussion Paper 2.

Kumar, N. and Pradhan, (2003). J.P Economic Reforms, WTO and Indian Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Industry: Implications of Emerging Trends. Dharwad: Centre for Multidisciplinary Development Research, CMDR Monograph Series No. 42.

Muraleedharan, V. R. (1999). Characteristics and Structure of the Private Hospital Sector in Urban India: A Study of Madras City Small Applied Research Paper No. 5.

Nandraj, S. and Duggal, R. (1997). Physical Standards in the Private Health Sector—A Case Study of Rural Maharashtra. Mumbai: Centre for Enquiry into Health & Allied Themes (CEHAT).

Narayana, D. (2001). Macroeconomic Adjustment Policies, Health Sector Reform and Access to Healthcare in India, Study Report, Trivandrum: Centre for Development Studies.

Nayantara, N., Puttaswamaiah, S. and Mishra, A. (2003). Economic Reforms and Health Sectors in India with Special Reference to Orissa, Karnataka and Maharashtra—Reflections from NSS 28th, 42nd and 52nd Rounds and CMDR Field Survey Data. Dharwad: Centre for Multi-disciplinary Development Research (CMDR), Dissemination seminar on ‘Economic reforms and the health sector in India’, 11–12th February 2003.

Panchamukhi, P. R. (2000). Social impact of economic reforms in India: A critical appraisal. Economic and Political Weekly; 4th March: 836–47.

Price, D., Pollock, A. M., and Shaoul, J. (1999). How the World Trade Organization is shaping domestic policies in healthcare. The Lancet; 354: 1889–92.

Purohit, B. V. (2001). Private initiatives and policy options: recent health system experience in India. Health Policy & Planning OUP; 16(1): 87–97.

Qadeer, I. (2000). Healthcare systems in transition III. India, Part I. The Indian experience. Journal of Public Health Medicine; 22: 25–32.

Rangarajan, C. (1998). Indian Economy: Essays on Money and Finance. New Delhi: UBS Publishers’ Distributors Ltd.

RBI. Annual Report 2009–10. (2010). Mumbai: Reserve Bank of India.

Selvaraju, A.(2003). Healthcare Expenditure in Rural India, Working Paper No. 90. New Delhi: National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi.

Shariff A. (1999). India: Human Development Report: A Profile of Indian States in the 1990s. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Than Sein, U. and Rim, P. C. (2001). Health policy: Multilateral trade agreements. Regional Health Forum; 5: 1–20.

UNFPA. (1997). India: Towards Population and Development Goals. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Varatharajan, D., Sadanandan R., Thankappan, K. R., Mohanan Nair, V. (2002). Idle Capacity in Resource StrappedGovernmentHospitals in Kerala: Size, Distribution andDeterminingFactors. Thiruvananthapuram: Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Achutha Menon Centre for Health Science Studies.

Varatharajan, D. and Evans, D. B. (2010). Fiscal space for health in resource—poor countries, Geneva, WHO, World Health Report 2010, Background Paper No. 41.

WHO. (2001). Globalization, Trade and Public Health: Tools and Training for National Action. New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Report of an Inter-country Expert Group Meeting, WHO Project No. ICP OSD 001.

WHO. (2004). The World Health Report 2004: Changing History. Geneva: World Health Organization.

WHO. (2010). India tries to break cycle of health-care debt. Bulletin of the World Health Organization; 88, 486–87. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/8877/10-020710.pdf.

WHO (2010) World Health Statistics 2010, Geneva, World Health Organisation.

World Bank. (2004). World Development Report 2004. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2004.