Early in 1937, Ward Kimball was not happy about working for Walt Disney. As a matter of fact he was seriously thinking about quitting the studio. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was in the final phase of production, and every artist involved with the film was working enthusiastically and long hours to meet deadlines. Yet Kimball could not share the crew’s sentiment, he was brooding. Practically all of his animation had just been cut out of the movie.

He was told that his sequence involving the seven dwarfs eating soup proved irrelevant to the film’s plot line. Another animated section that showed the dwarfs building a bed for Snow White had been eliminated as well for the same reason. Ward had contributed scenes for this piece as well. What remained of his work were a few shots with the vultures, as they fly above the Witch, who is making her way into the forest toward the dwarfs’ cottage. A meeting with Ward and Disney was scheduled, and its outcome could have been the end of Kimball’s career at the studio.

What happened instead proved that Walt Disney was a master when it came to dealing with any of his artists’ problems. Ward left that meeting anxious to get back to his drawing board. Walt had just given him a brand new assignment, a character who would play an important role in the studio’s next animated feature Pinocchio. Kimball was going to develop and animate Jiminy Cricket, and he was promoted to supervising animator. Disney’s passion as well as his powers of persuasion had just helped him to avoid losing one of his most important artists. Kimball’s subsequent career at the studio was long and fruitful, but not without the occasional bump in the road.

Ward Kimball was hired on April 2, 1934. He was placed into the in-betweener pool, which included a group of newcomers who learned the ropes by assisting experienced animators. After helping out on short films like The Wise Little Hen and The Goddess of Spring, he was finally given the chance to do some of his own animation on the short Elmer Elephant. Ward impressed senior animator Ham Luske with his first attempts as a solo animator. This led to an assignment that catered to Kimball’s musical talents. In the short Woodland Café he animated several jazz musicians portrayed by insects. The energy of the jazzy musical track is perfectly captured in the fast-timed animation. Ward’s own enthusiasm as a musician comes through in the insects’ exuberant, rubber-hose movements. The feet are tapping, hands work themselves in and out of camera, and the whole body reacts to the musical rhythm. These scenes caught the attention of many people at the studio, and perhaps later gave Walt Disney the idea to have Ward develop a certain insect for the film Pinocchio.

Spirited, perfectly timed musical moves signal Kimball’s attitude toward his work. Pure fun.

© Disney

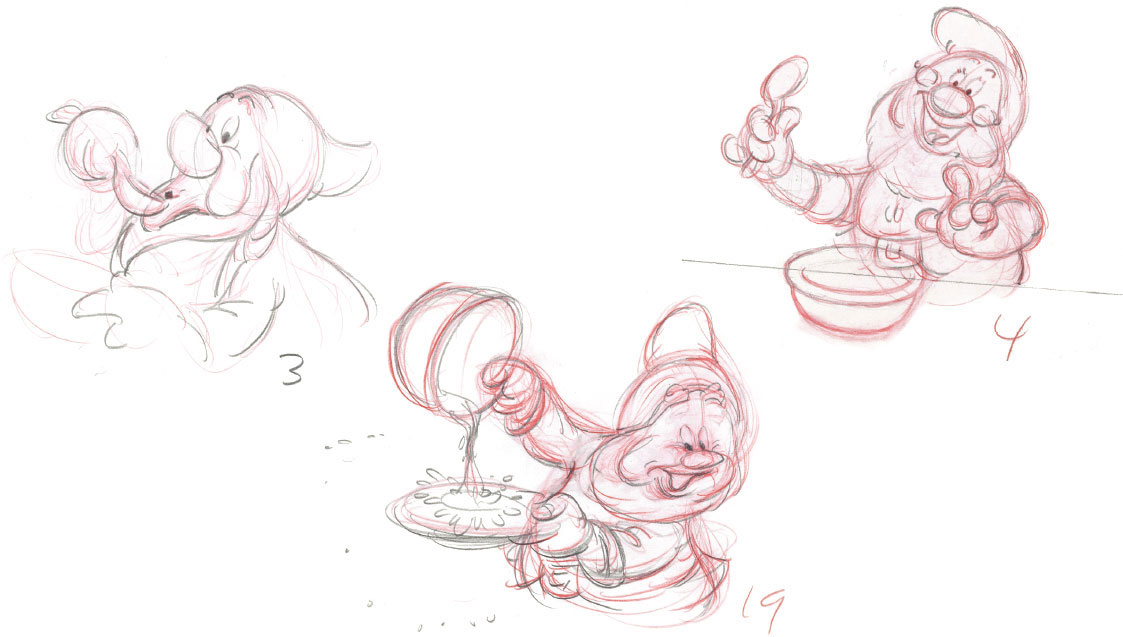

The looseness showcased in Kimball’s early animation was much more suitable to cartoony characters than realistic ones. When the studio began work on Snow White, it was no surprise that Ward ended up in the dwarfs unit. His main sequence might have been cut from the film but looking at individual drawings from this deleted section, we can only marvel at the way Ward exaggerated the dwarfs’ faces without ever losing the characters’ charm.

When these scenes were deleted from Snow White, Ward very nearly quit working for Walt Disney.

© Disney

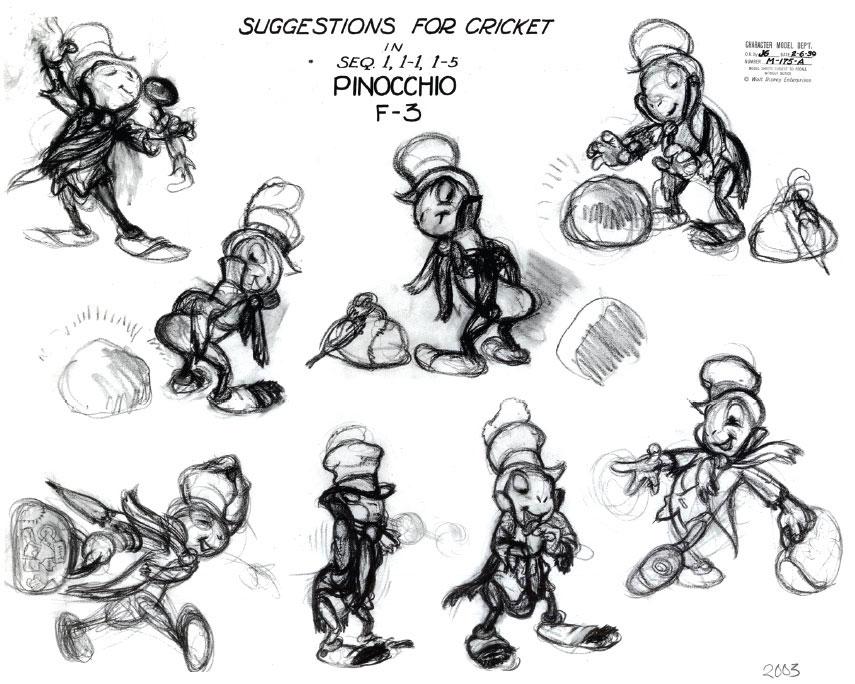

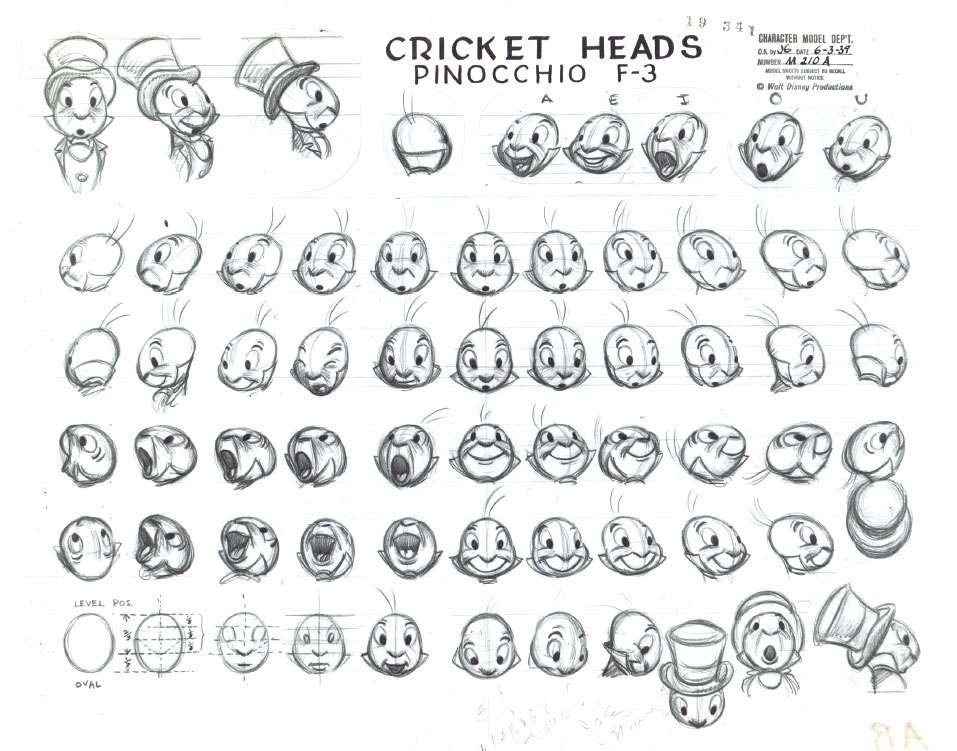

Charm was a quality Ward had a very hard time getting into his next assignment—Jiminy Cricket from the film Pinocchio. “A cricket looks like a cross between a cockroach and a grasshopper,” he stated in a later interview. Naturally, as a Disney artist, it is obvious to start researching the characteristics of the real insect. But each time Ward would show Walt Disney an updated design of Jiminy for approval, the boss’ response was always the same: too ugly, lacks appeal. After more frustrating attempts and virtually eliminating any resemblance to a real cricket he finally succeeded in getting Walt’s OK. By this time Jiminy looked appealing, but not much like an insect at all. Instead his proportions were similar to Mickey Mouse’s.

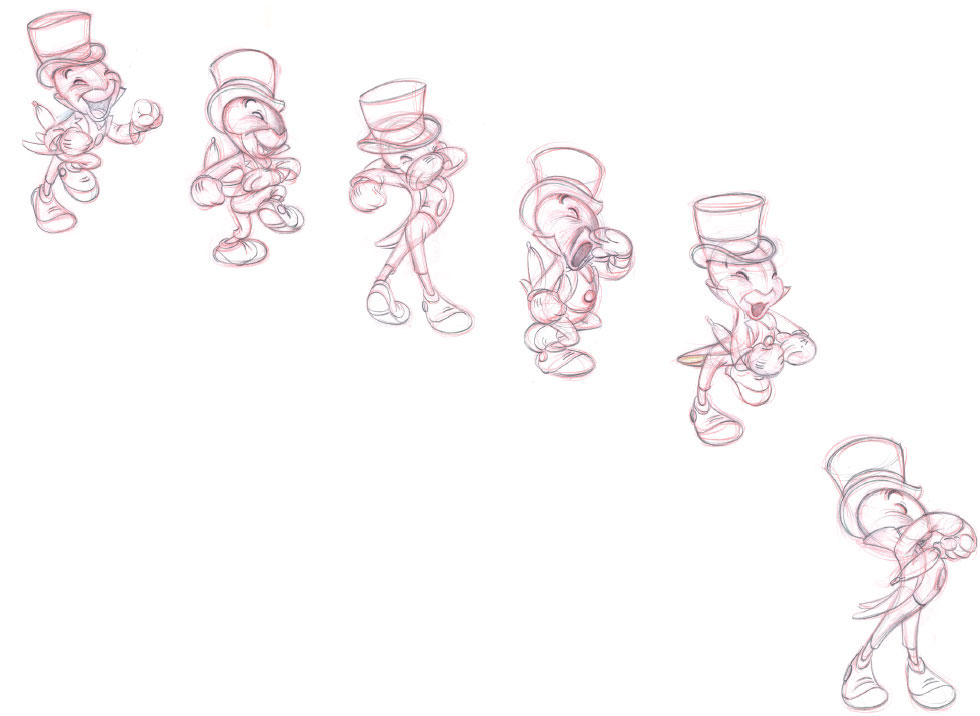

Early designs based on real crickets and (opposite) Kimball’s final version of Jiminy.

© Disney

Ward might not have been entirely happy with Jiminy Cricket’s appearance, but he most certainly succeeded in developing his personality as a caring and likable mentor to Pinocchio. He might look like a little man without ears, but he jumps high like a real cricket. The timing in his acting is quick and contrasting, but the overall performance is always sincere and believable. The audience likes Jiminy instantly, because he cares so much about Pinocchio. Just like Mickey Mouse, his poses are strong and easy to read. Occasionally Ward gave him complex dance moves that are a joy to watch. After Pinocchio comes to life with the help of the Blue Fairy, they both celebrate while singing “Give a Little Whistle.” Again Ward’s musicality comes forward during Jiminy’s line: “And always let your conscience be your guide.” The dance steps are incredibly complicated when analyzed; every body part is doing something differently, yet the whole works in rhythmic perfection. Complex scenes like these require 24 drawings per second (simple and slow-moving scenes usually involve only 12). Here every single drawing is all-important and needs to be made by the animator. There aren’t any in-betweens that could be passed on to the assistant.

All drawings are key, there are no in-betweens when animating a scene this complex.

© Disney

Few Disney feature characters achieve top stardom like Jiminy Cricket. Once audiences have embraced such a personality, they are eager to see more appearances. Jiminy and Tinker Bell from Peter Pan both have become icons who represent not only The Walt Disney Studios, but animation as a whole. These ambassadors introduce TV shows, they are main attractions in theme parks and have become popular merchandise characters. In other words their popularity has afforded them an afterlife. Kimball’s next animated character required again careful synchronization between movement and music. Bacchus from the “Pastoral” sequence in Fantasia and his donkey-unicorn Jacchus are an unequal pair. The little mule has a hard time carrying the oversized god of wine, but his off-balance moves presented possibilities for funny character animation. Bacchus is interested in only two things, wine and the alluring “centaurettes.” A chubby and intoxicated personality like him moves in unsteady and wobbly ways, which are all synced here to the beat of Beethoven’s music. Even though there are some fun moments to animate, particularly during the dance, Ward was not very fond of this assignment. The character’s design as well as his role in the film didn’t come up to his standards. He enviously watched his colleagues who pulled out all the stops when animating the hilarious parody of the ballet “Dance of the Hours”. “Once in a while something perfect comes along,” Ward stated years later. “The ‘Dance of the Hours’ turned out as perfect as it gets.”

Bacchus and Jacchus might not have been favorite assignments, but Ward still managed to animate them with comic gusto.

© Disney

Beautifully drawn, outrageous poses prove how much fun the animator was having with his assignment. Ward liked to break rules of logic when it the stood in the way of entertainment. A philosophy that would become a Kimball trademark.

© Disney

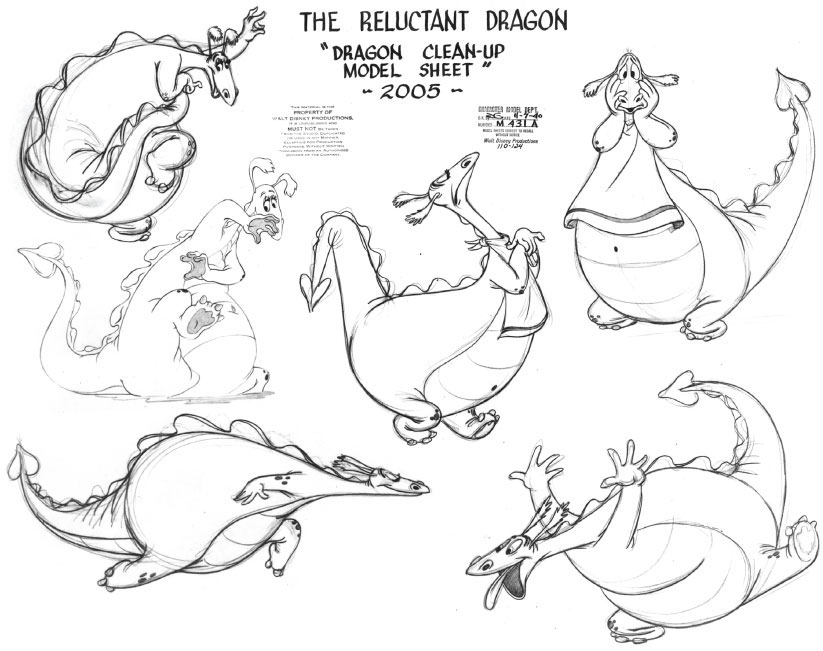

In the film The Reluctant Dragon, Ward finally found a role that offered a tour de force acting opportunity: a cartoony looking dragon who is expected to put up a fight with local knights.

But instead the Dragon is petrified at the mere thought of a combat—it turns out he is a poet who enjoys his afternoon tea. Actor Barnett Parker’s voice suggested a flamboyant type who would express himself through theatrical gestures. Ward charged at this rich material and created one of his all-time great animated personalities. His acting choices are perfectly in line with the dialogue recordings: flamboyant acting at its best. At one point the Dragon invites the Boy to a picnic on his belly. He decides to recite a poem he wrote about an upside-down cake. He so sympathizes with the cake’s dilemma because its top is on the bottom, he is even moved to tears and gives it a little kiss. It is absolutely hilarious to see how sincere the dragon is during his performance. Kimball’s poses communicate a character who is acting in front of an audience. A few years ago Ward was reminiscing about the character and said that the Reluctant Dragon was probably the first gay character in the history of animation.

By now Kimball’s expressive and inventive style of animation was recognized and admired by most of his co-workers. It came as no surprise that Ward would not join the Bambi unit, instead he was offered to develop a group of crows for the film Dumbo. These birds played a crucial part in the story. They first ridicule Dumbo after being told that he had flown into a tree. Eventually they become convinced and try everything they can to make Dumbo take to the sky again.

Ward particularly enjoyed animating their song number “When I See an Elephant Fly.” He managed to create five different crow personalities with Jim Crow as the boss. Everybody moves according to their body type—skinny, tall, or chubby, etc. As they walk and strut, singing along, the timing is punchy and fluid at the same time. Jim Crow at one point rotates one of his legs completely illogically, anatomically speaking, before kicking it out. Two other crows lean against each other dancing away from the camera, except their combined silhouette only shows two legs instead of four. Breaking the rules of logic in order to present something unexpected is a quality Kimball relished. Some directors and animators at the studio questioned this approach, thinking that believability is being lost with this kind of surreal animation. But Ward remained undeterred, this was the way he saw the medium of animation, an ongoing experiment in how to entertain in new ways.

Nonsensical staging and movement for “When I See an Elephant Fly.”

© Disney

During the early 1940s Ward brought his unconventional sensibilities to Disney short films as well. For the Mickey Mouse short The Nifty Nineties, Ward got to animate a very unusual sequence, one that involved two characters who turned out to be caricatures of Disney animators.

The first one was Ward himself, the second one was his friend, animator Fred Moore. The walls of Kimball’s office had long been filled with gag drawings depicting these two in mischievous situations, so it didn’t seem far-fetched to utilize their designs as animated vaudeville performers for an audience that included Mickey and Minnie Mouse. They tap dance across the stage, then pause for a moment, so Ward can tell Fred a joke: “Hey brown eyes, who is that lady I saw you with last night?” “That was no lady, that was my wife!” Laughter follows, and Ward hits Fred on the head with a hammer. This is slapstick cartoon business, and Kimball tried everything to present it in a funny ways. On Fred’s last dialogue line, the word wife is animated by suddenly enlarging his mouth disproportionally. This is an odd choice, but because it comes unexpectedly it looks very funny. Ward proves again that you can’t go wrong by surprising the audience.

Fred Moore as silly vaudeville entertainer.

© Disney

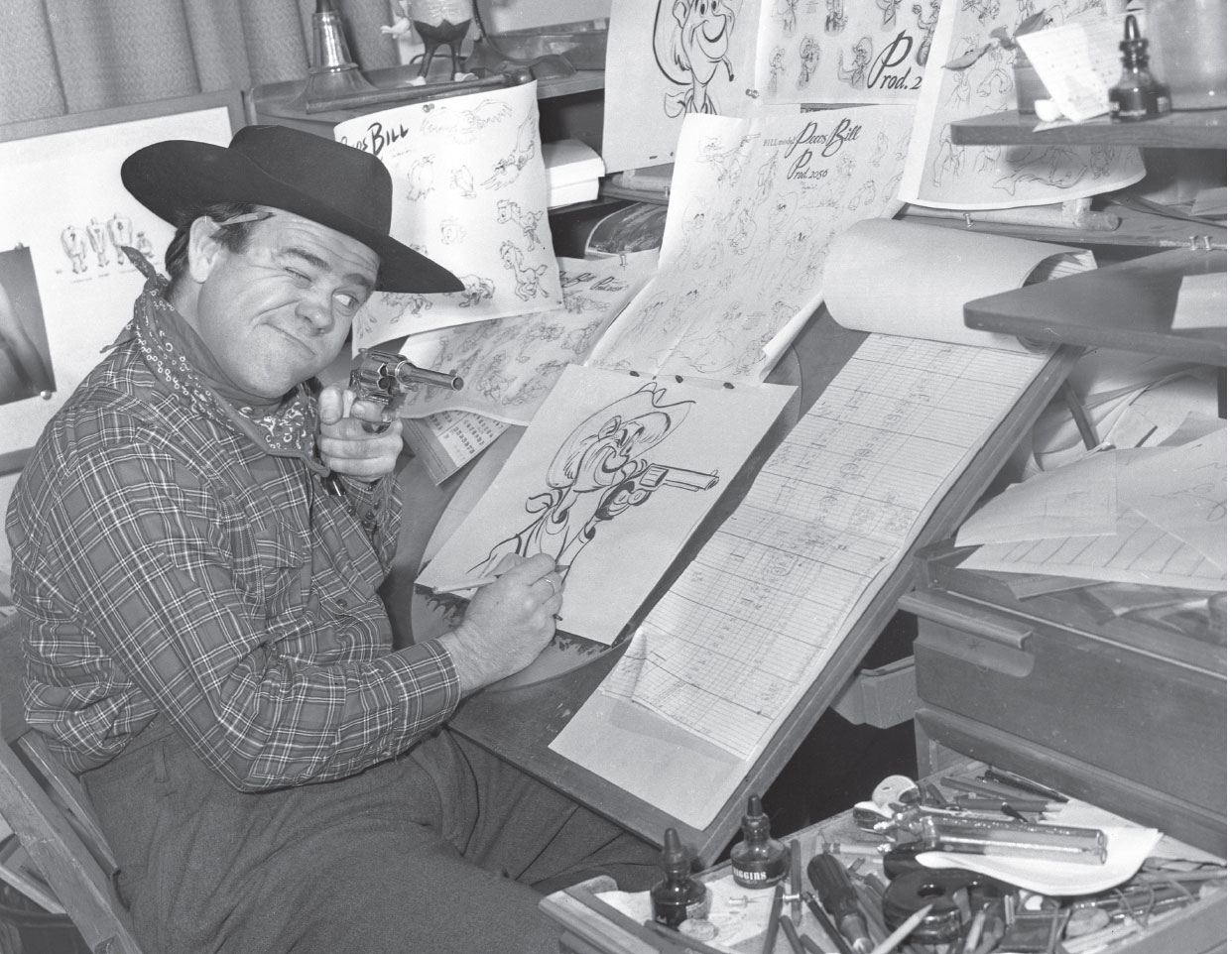

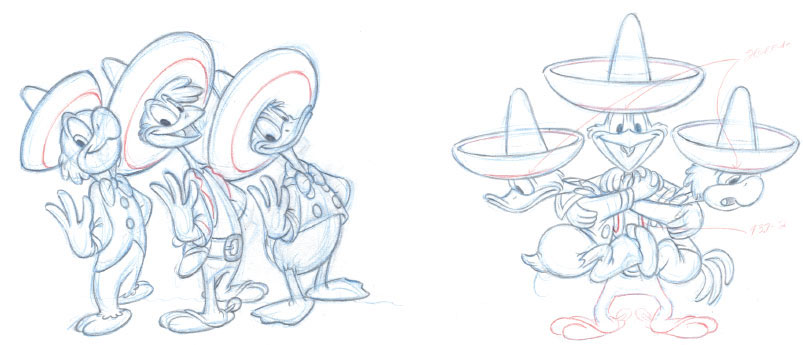

More juicy animation assignments kept coming Ward’s way. The 1945 film The Three Caballeros featured a big song number with Donald Duck, Panchito Pistoles, and José Carioca. Kimball, who animated the whole musical number, explained his approach for the animation during a 1984 interview:

I was given this long song that went on for three or four minutes with no business. So I listened to the song for about a week. I turned all the lights off in the room and just listened to the song, visualizing it. I said there is nothing I can do except being literal about it. When they say: “We’re three happy chappies with snappy serapes,” all of a sudden the serapes appear. One of the first criticisms, when the director saw the pencil test, was: The duck goes out on the right, and he comes in on the left. And the rooster goes out on the top, and he comes in from the bottom. You can’t do that, it’s not logical. You have to have these tie ups, you have to make sense. And I said: Look, who cares? A guy runs out on the left and comes in on the right. I mean, that gives it its flavor, its craziness.

Luckily when Walt saw the sequence, he had no objections whatsoever. And the song’s animation remained intact.

Ward turned the song number in The Three Caballeros into one of animation’s most hilarious and surreal moments.

© Disney

Walt Disney knew by now about Ward’s strength as an animator who, with each assignment, strived for new ways of doing things. Kimball himself stated once that animation requires an endless amount of drawings, so why repeat yourself when there is a chance to do something in a different way? As wacky as some of his scenes might have turned out, they still have a believable quality because Ward was an excellent draftsman who animated his characters with real weight. Without weight there is only graphic movement, which involves an audience only to a point. But by moving different parts of the body separately and timing them based on what they are made of (body mass, hair, clothing) the animated whole will come to life. Ward applied these rules in everything he did, and his assignment to animate several characters for the short Peter and the Wolf was no exception. He drew key scenes with the Sasha the cat and Sonia the duck.

But his most inventive and original animation can be seen when the three hunters arrive. Mischa, Yascha, and Vladimir are entirely comical characters. As huners they look about as effective as the Three Stooges. When the little bird Sasha tries to get their attention to inform them about Peter’s plight, the befuddled and confused troop runs around in circles before regrouping.

Kimball’s way of moving these characters is nothing short of breathtaking. As they make their way through the forest, the leg movements range from tip-toeing to long strides. When they find out about the danger ahead, they charge forward, propelled by unrealistic circular leg motion.

Ward squeezes every bit of fun out of this trio, which includes constant bouncing of their hats as well as loose follow-through action in their clothing.

It is obvious that Kimball relished bringing these clumsy hunters to life.

© Disney

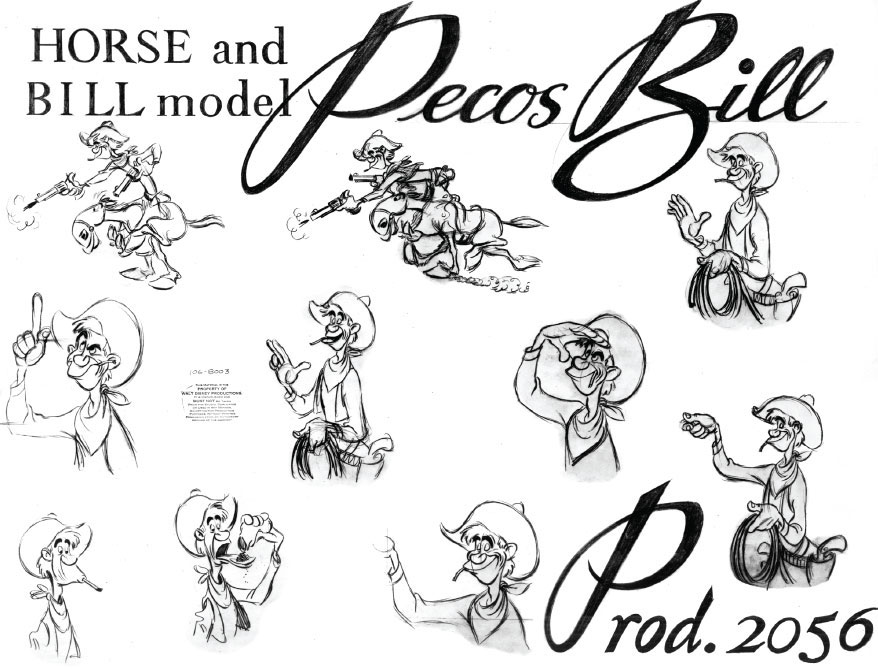

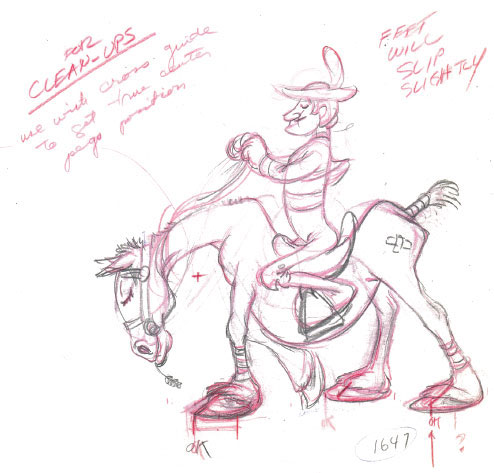

Ward’s next character assignment would be comical again, but a little more skilled and accomplished than the three Russian hunters. Pecos Bill is part of the 1948 full-length feature Melody Time. The character was primarily animated by Ward Kimball and Milt Kahl, two highly skilled animators with somewhat different ideologies. Kahl insisted on masterfully drawn animation that showed natural, believable movement. Kimball on the other hand was driven by a need to experiment and invent in order to maximize the entertainment. Astonishingly Pecos Bill works seamlessly in continuity, there is only one version of the character on the screen. Ward animated the opening scenes when young Pecos falls off a moving wagon. He is left behind and eventually raised by coyotes. He befriends an infant horse, later named Widowmaker. As adults we see the two of them bonding during outrageous adventures like chasing a cyclone as well as roping and pulling a raincloud from California all the way to Texas for drought relief. All this outrageous story material was perfectly suited for Kimball, who always preferred working with such impossible situations. He even animated a scene with Pecos and Widowmaker yodeling into the camera as they are riding along. In order to show the mouth actions clearly Ward underplayed the overall body movement, so the viewer remains focused on the expressive yodeling phrasing.

From a technical point of view, these scenes were very involved. The horse on one hand is running, jumping and rearing up, while Pecos on top is lassoing, shooting, and singing. The action analysis alone might have been too difficult for many animators, but Kimball made it look easy.

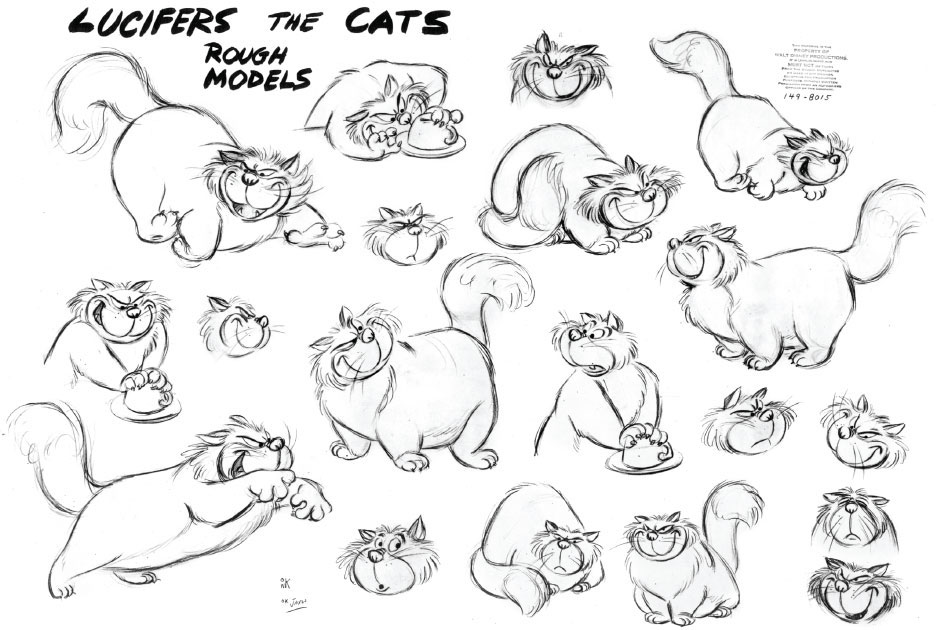

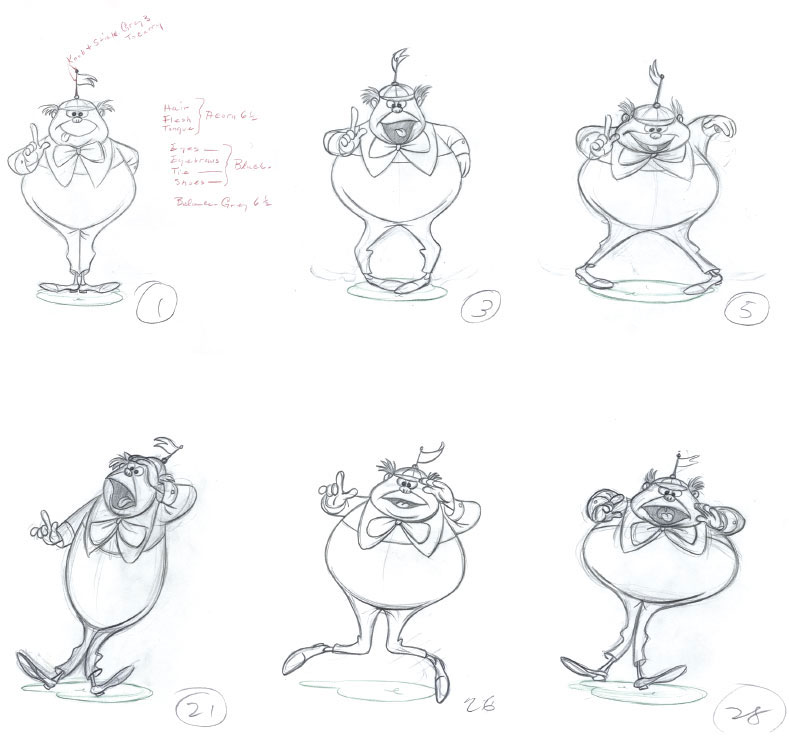

After animating scenes for both sections of the film The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, Ward joined the team that would re-establish the Disney full-length animated feature film with Cinderella. He was put in charge to develop the stepmother’s evil cat Lucifer, who often interacted with a sympathetic group of resident mice. At the time Ward was criticized for his design of Lucifer, as a cartoony, fat villain with almost no believable anatomy. The human cast was animated with the help of life-action reference, and their animation required careful drawing combined with realistic motion, in stark contrast to Lucifer. But Kimball didn’t care, this was the way he was going to approach the cat. And Walt Disney did not object, because he might have foreseen the type of entertainment Ward would come up with for the cat and mice. One sequence in particular turned out to be a comedic masterpiece. As Cinderella arranges breakfast items on trays for her stepfamily members, Lucifer frantically searches for the mouse Gus under the cups.

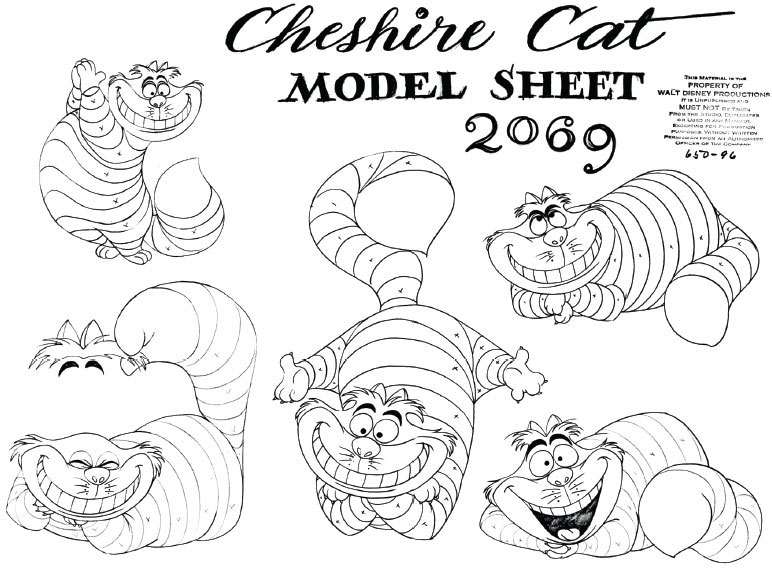

A model sheet made up from Kimball’s key animation poses.

© Disney

Kimball’s model sheet of Lucifer reveals strong poses and evil expressions, in spite of an overall cartoony appearance.

© Disney

This is a fight against time, because soon the trays will be taken upstairs. Lucifer’s paranoid timing accelerates, because he knows the mouse is somewhere under one of the cups. The fact that the audience knows at all times where Gus is hiding just adds to this hilarious pantomime scene. Even animation maestro Milt Kahl admitted years later: “I could never have done anything like that.”

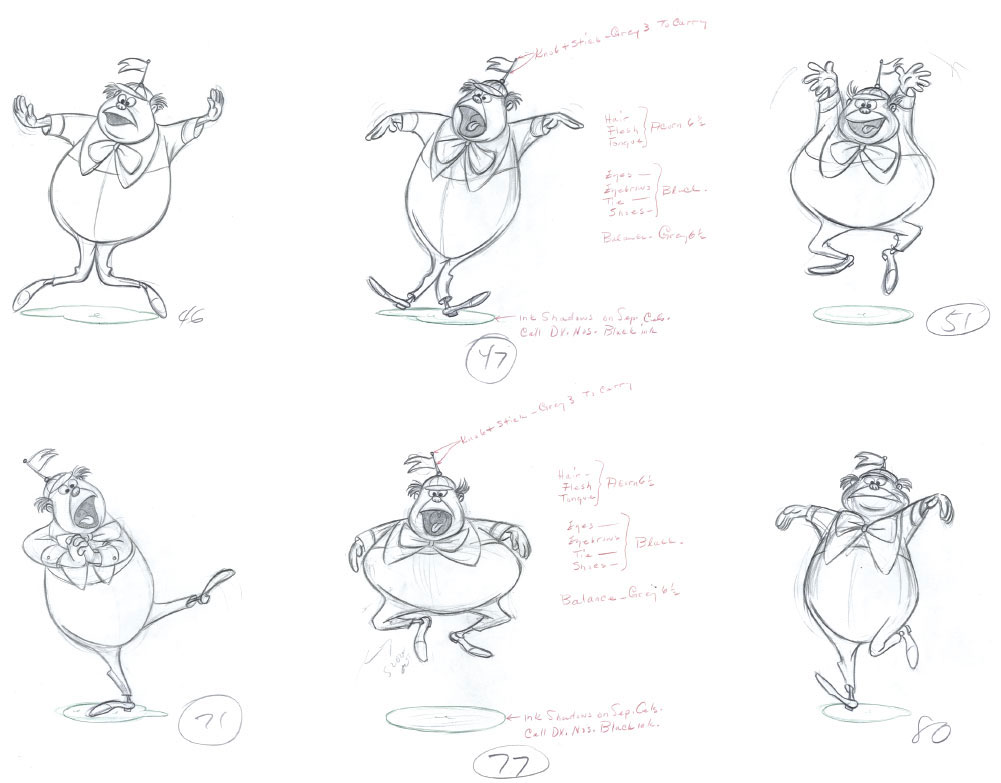

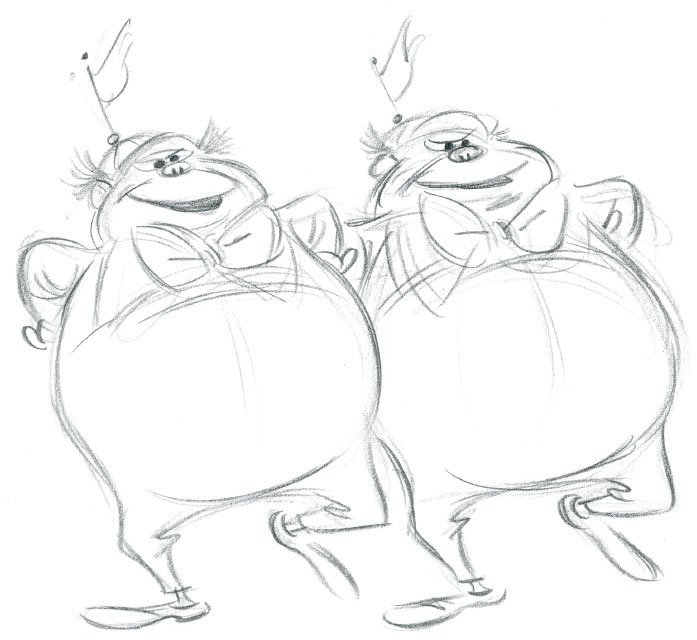

Ward again avoided getting cast on a realistic character when production began for Alice in Wonderland. This time he was given the opportunity to animate a whole range of eccentric personalities. Although some of them were human characters, they did not conform to the world Alice came from. After all, this was Wonderland. Tweedledum and Tweedledee move as if their bodies were water balloons. They constantly bounce into each other as they introduce themselves. Actually Ward uses this physical contact to great comical effect. The eccentric animation is perfectly timed to lively music and silly sound effects. As so often before, Kimball enjoys inventing unusual leg movements that go against any logic. He breaks the knees in order to get a wacky effect, anything to make them move in unrealistic but entertaining ways.

Tweedledum and Tweedledee move as if their bodies were water balloons.

© Disney

What made the Mad Tea Party so outstanding was the fact that absolutely nothing made sense, yet poor Alice tries repeatedly to reason with crazy characters like the Mad Hatter and the March Hare. Although some live action was filmed, Kimball’s animation shows no trace of any such reference. He did pick up pieces of business from actors Ed Wynn and Jerry Colonna, but by incorporating this into his broad animation, the results look original and fresh. This kind of lively, cartoony animation can easily look overactive when not timed properly. In all of this frisky movement there needed to be moments of pause in order to show the characters thinking, otherwise any personality statement gets lost in hectic graphic motion. Ward of course knew this very well. He would take advantage of these quieter intervals and add funny but subtle bits of action like an ear wiggle or unusual dialogue shapes.

The equally mad March Hare.

© Disney

The Mad Hatter’s tongue was used to animate his dialogue with a lisp.

© Disney

The Cheshire Cat was animated in an entirely different way. Ward underplayed this character to bring out his schizophrenic personality. Different parts of the cat’s body appear and disappear slowly, and his smooth movements are peculiar and offbeat. He can literally remove his head and stand on it. He also gestures with his hind legs. Kimball considered the Cheshire Cat to be the real mad one in the film.

The psychotic Cheshire Cat might move slowly, but he expresses pure insanity.

© Disney

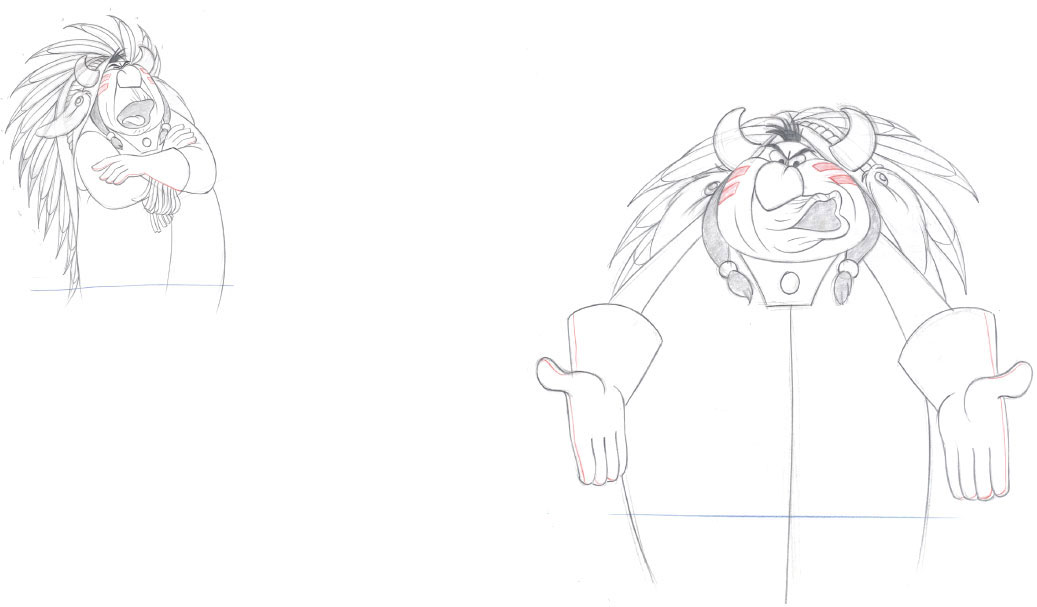

There was not nearly as much madness to be found in Disney’s next animated feature, Peter Pan. The title character as well as the children were conceived as being real flesh and blood characters, not the kind of assignment Ward would look forward to getting involved with. Around this time, several of the other animators voiced their disapproval of not ever getting the type of juicy assignments that Ward had enjoyed over the years. Marc Davis stated that he and Milt Kahl most of the time ended up animating the realistic human characters, while Kimball had all the fun doing cartoony stuff. Nevertheless, Walt Disney knew his animators’ strengths (and weaknesses) very well, and he cast Ward on the Indian Chief. Needless to say this imposing, authoritative character turned out to be as entertaining as anything Ward had done in the past. In most of the Chief’s scenes he acts very serious and stern, not very compelling qualities. What Ward focused on, in order to get humor into the animation, was the way the Indian Chief talked. His large mouth configuration is somewhat unique with a long upper lip and deep wrinkles. Unique mouth shapes and punchy timing give great interest to his dialogue scenes. It’s just fun to see him say the name of his daughter Tiger Lily and watch his tongue wiggle inside his mouth.

Unusual dialogue animation helped to enrich the Indian Chief’s personality.

© Disney

When work began on Lady and the Tramp, Ward realized that the trend toward realism in Disney features meant fewer opportunities to express himself. Perhaps the two villainous cats Si and Am could be handled in a way that would be in line with his artistic sensibilities. Kimball went all out to make them vicious, zany, and unpredictable. Unfortunately the results did not fit in with the overall styling of the film, and Ward was taken off the picture. He subsequently took on the job of director/animator for the experimental musical short film Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom, which presented the history of musical instruments throughout the world. Back in his element, Ward pushed the boundaries of Disney animation, this time on a smaller budget. Limited animation had been pioneered before at other animation studios like UPA, and Ward was fascinated by the challenge of finding entertainment with minimal motion on the screen. Very often the character’s body is held in one drawing, while only a hand or an eye moves. The overall visual statement can be much more poignant than what full, all-involved character animation offers. Traditional Disney characters become living, breathing beings, but in limited animation the motion is greatly reduced, and the viewer accepts that flat drawings communicate a more restrained kind of acting.

Modern graphics help alter the conventional Disney style.

© Disney

Ward once again did not fit in with the studio’s next animated feature Sleeping Beauty, where the focus was on stylized but realistic drawing and serious storytelling. Luckily other opportunities came along when Disney entered the world of television. A series of shows dealing with man’s future in outer space was being developed, and Kimball was put in charge as a director. Limited animation was again used to achieve dramatic as well as comical results. These TV shows were hugely successful, and Ward later recalled that this period at the studio might have been his happiest.

After such a creative and innovative chapter as a director at the studio, Ward all of a sudden found himself at odds with his boss, Walt Disney, while he was supervising sequences on the mostly live-action film Babes in Toyland. Walt was unhappy with Ward’s story work as well as the choices he made for casting actors. In heavy disagreement, Ward found himself “demoted” back to animator. In the early 1960s he was put to work on TV shows featuring the new character Ludwig Von Drake. Kimball animated several entertaining sequences, but the old Kimball animated spark was missing. Nevertheless, after Walt’s death in 1966, Ward still experienced a couple of career high points. He directed the Academy Award-winning animated/live action short It’s Tough to Be a Bird, and in 1971 he served as animation director for the mostly live-action film Bedknobs and Broomsticks. The movie’s highlight is a soccer game played by various animated animals on the island of Naboombu. Here the Kimball touch is evident in almost every scene, as the anthropomorphic characters play the game by making use of their animal characteristics. The goalkeeper elephant shoots the ball across the field with his trunk, while the cheetah runs so fast that his feet catch on fire. This is a hilarious sequence that only reaches comedic highs because of Ward’s involvement. It turned out to be his last contribution to Disney animation before he retired in 1973.

The film Mars and Beyond explored the possibilities of alien life forms.

© Disney

Ward Kimball’s long career as a Disney animator and director is unique; no one else put that much effort into expanding the horizon of character animation. With each assignment he kept asking himself: What can I do differently this time around? His hyper experimental spirit was always grounded in superb classic draftsmanship and in a great sense for original comedy. No matter how off-the-wall his characters might behave, they always came across as believable and enjoyable. Today’s animation community can still benefit and learn from Ward’s rich body of work, as well as his philosophy: why repeat yourself when there is a chance to do something different?

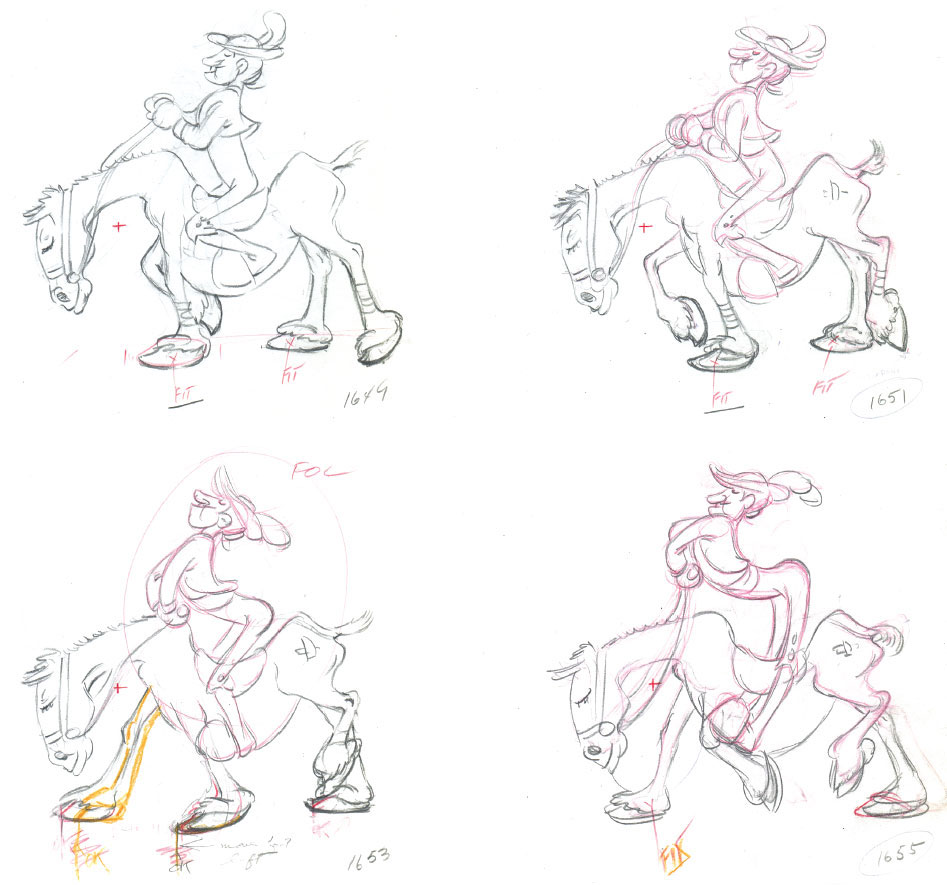

1938

PICADOR ON HORSE

ROUGH ANIMATION

Sc. 39

Ahead of Ferdinand’s planned bullfight, a line of various fighters parade into the arena before the matador. Kimball animated all of these characters. Their designs represent caricatures of Disney animators, and this picador on a dilapidated horse is star animator Bill Tytla. The fact that Ward placed him on such a battered horse shows that he is poking fun at his highly regarded colleague. The Tytla character moves ever so proudly up and down from the saddle, exuding an almost ridiculous amount of confidence.

The horse is animated by walking in place in accordance with the camera move. The feet seem to slide on the ground but, combined with the moving background, the connection between character and scenery is perfect. This method of working out a piece of action during a camera move was preferred by most animators. Using an alternate way of handling a scene like this, one would be animating the character physically across the page, and then on to another one. By staying in place would seem like a simpler way of doing this, but it required precise synchronization with the increments of the camera move.

These few drawings only represent a small portion of this long and labor-intense multi-character scene.

© Disney

© Disney

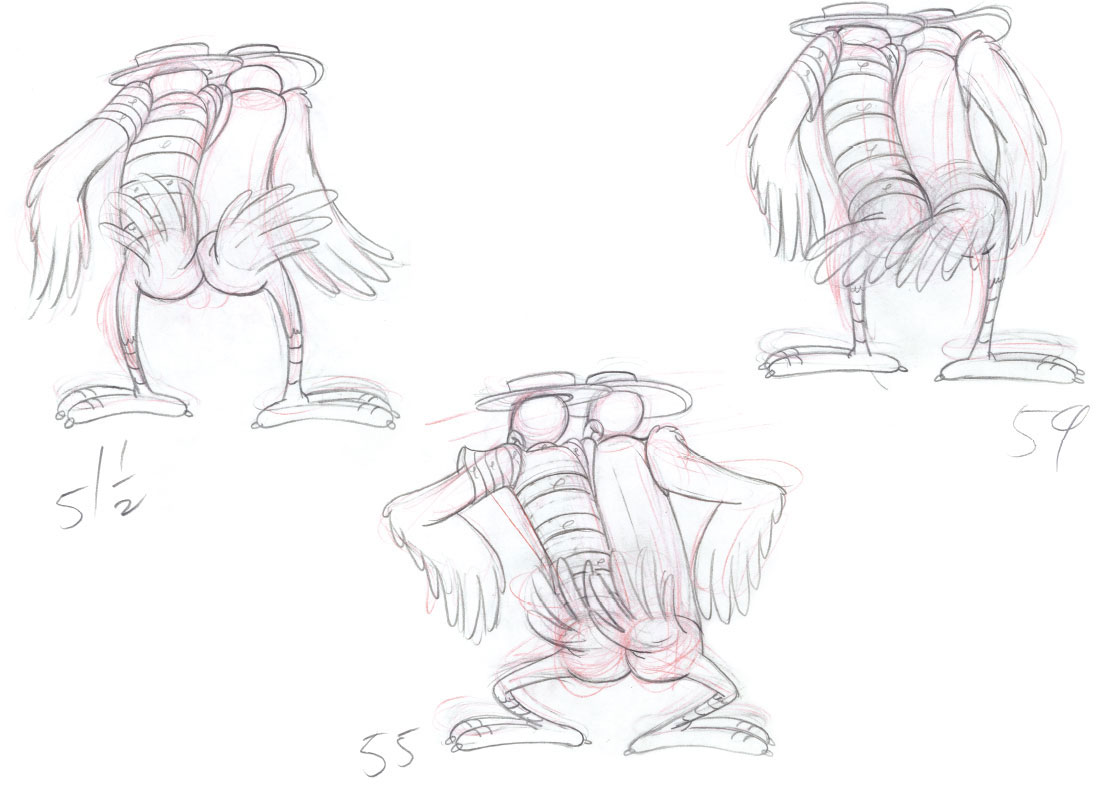

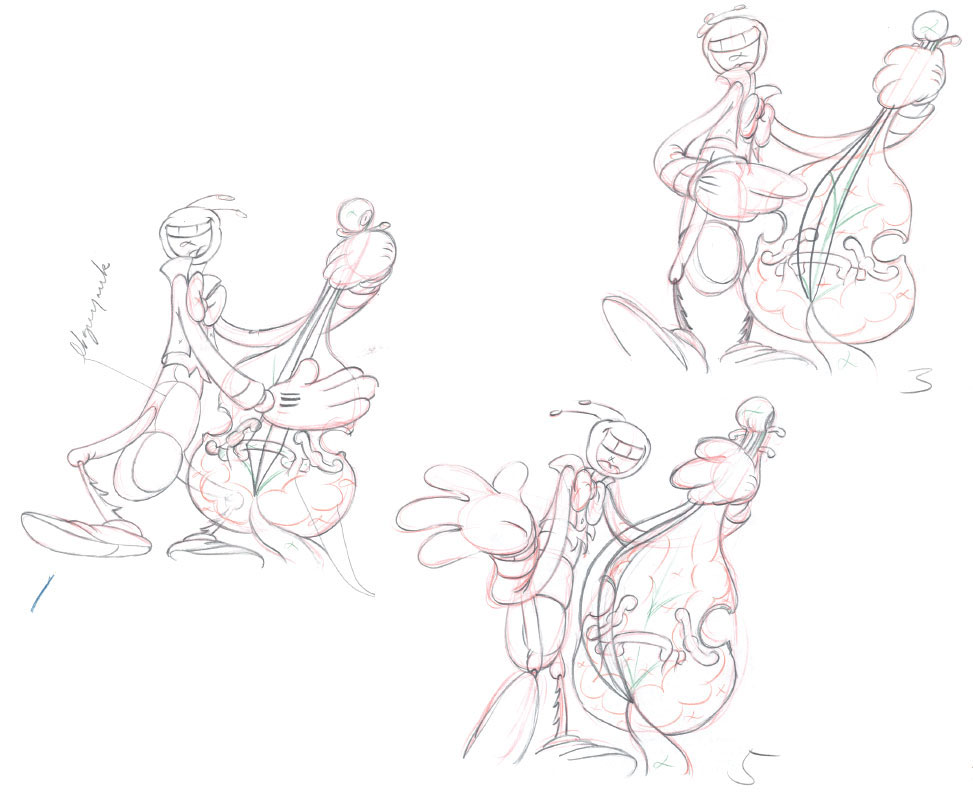

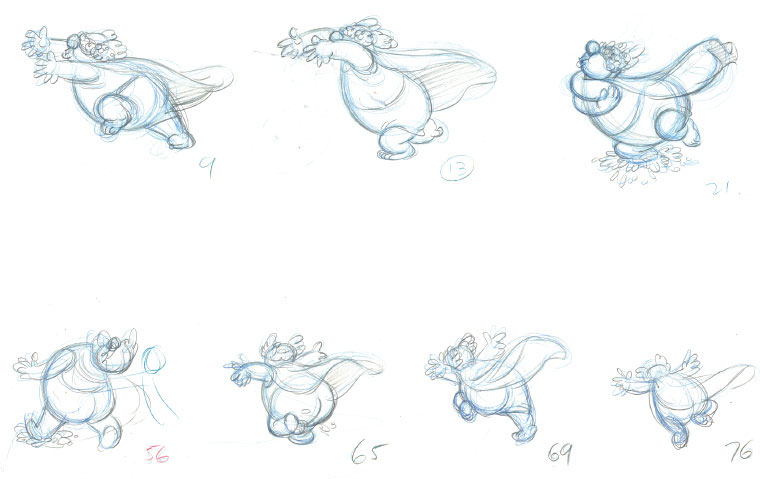

1940

BACCHUS

ROUGH ANIMATION

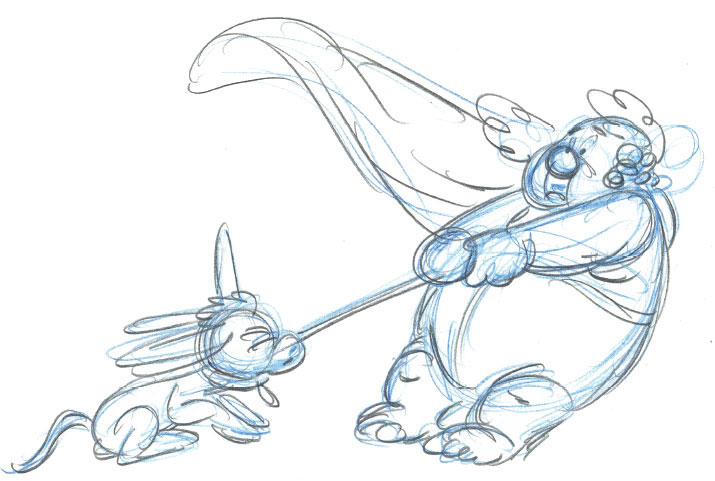

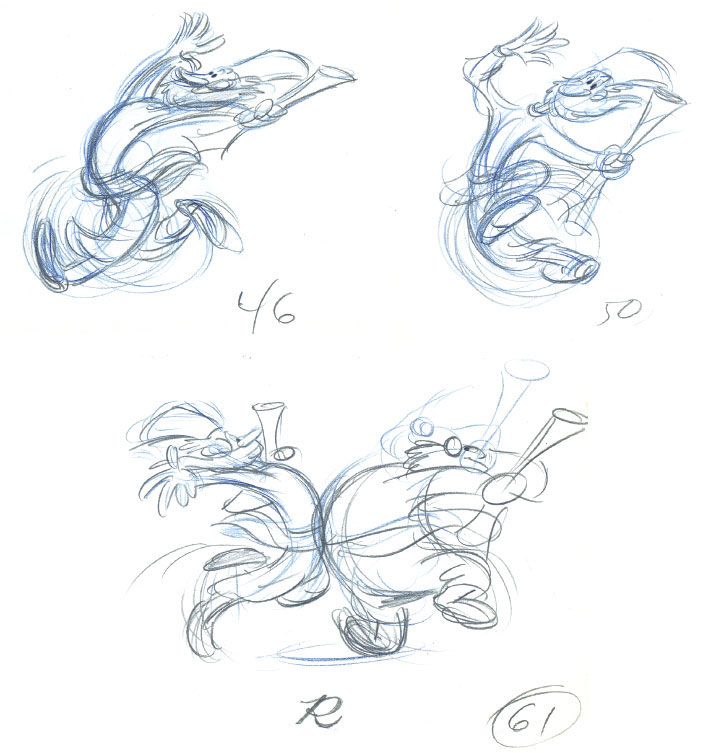

Seq. 4.3, Sc. 43

It is astonishing to see how rough Ward Kimball’s drawings for this scene are. And yet, he keeps control of this chubby god of wine throughout the broad animation, which is carefully timed to the music of Beethoven. Bacchus is chasing and interacting with various centaurettes. His body mass is treated like a water balloon that spins out of control at the end of the scene. The counter-movement of the long, soft cape adds to the overall fluid feel to the scene.

On some of the drawings Kimball indicated lightly key positions for centaurettes, which were later handled by animator Jack Bradbury.

© Disney

© Disney

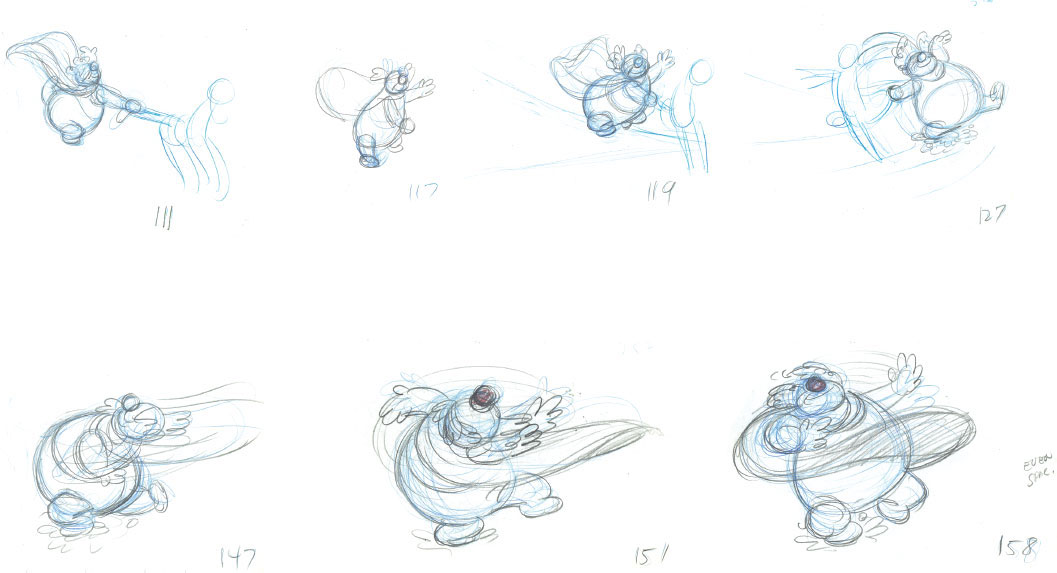

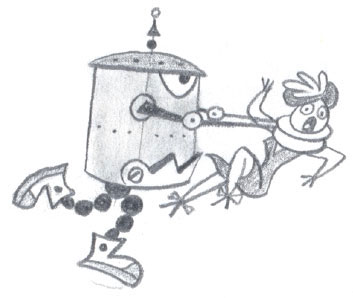

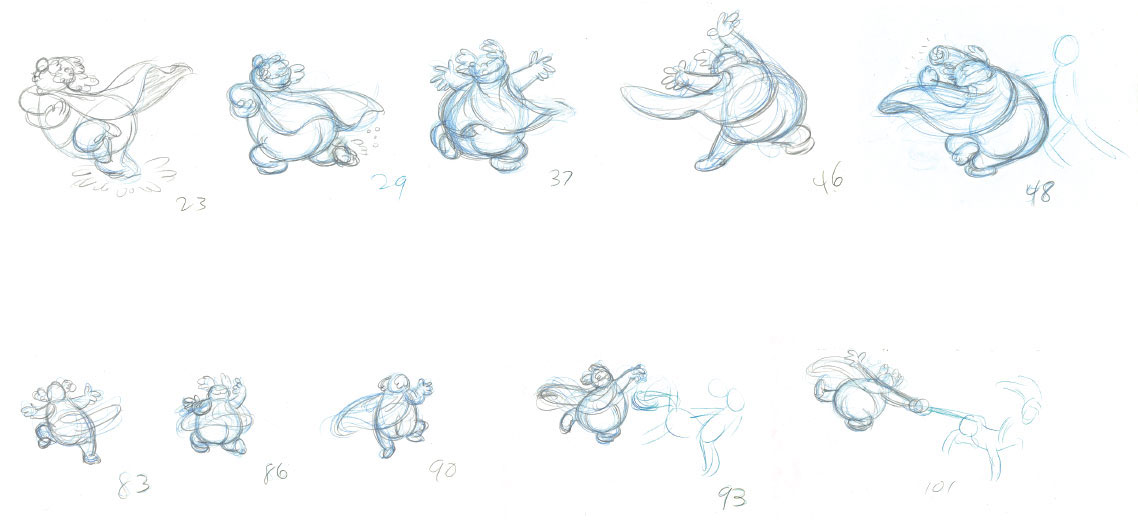

Make Mine Music / Peter and the Wolf

1946

HUNTERS

ROUGH ANIMATION

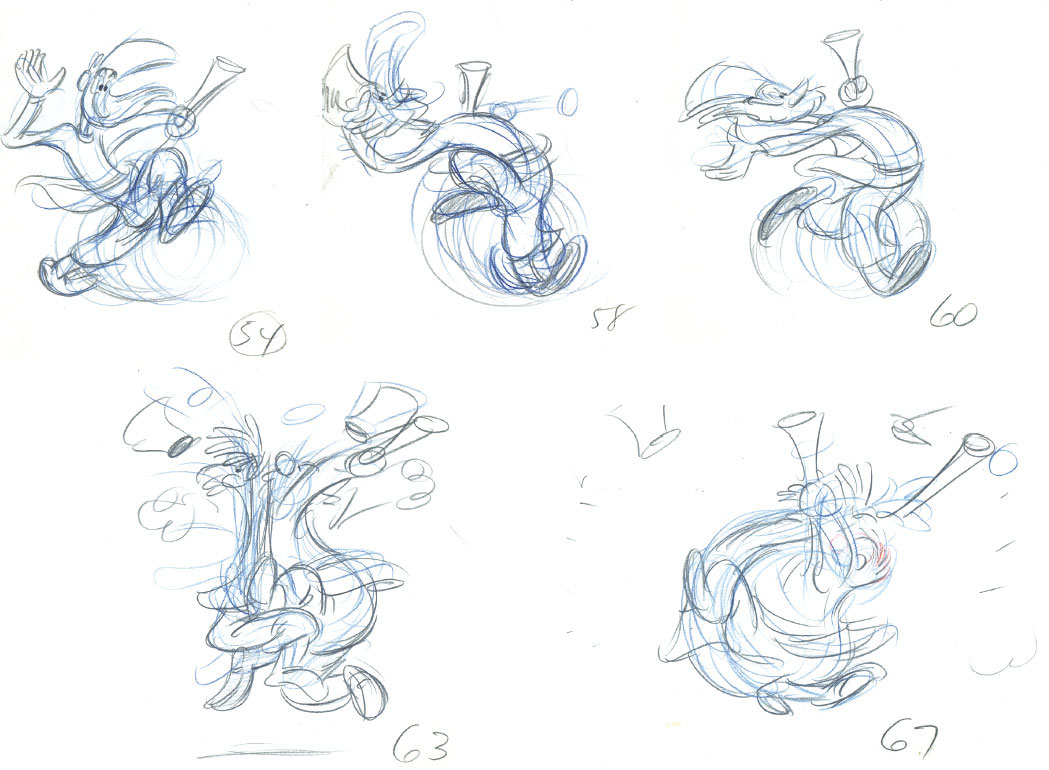

Seq. 7, Sc. 99

These few rough drawings show two of the three hunters being startled by Peter’s whistle sound coming from up high in a tree. They had all been informed of the boy’s encounter with the dangerous wolf, and their reaction is portrayed as a wild, nervous scramble of movements before running into each other.

Extremely broad action like this is played for comedy and paints the hunters as relatively harmless and confused characters.

This is a textbook example of two cartoony body masses smashing together, then separating before falling to the ground.

© Disney

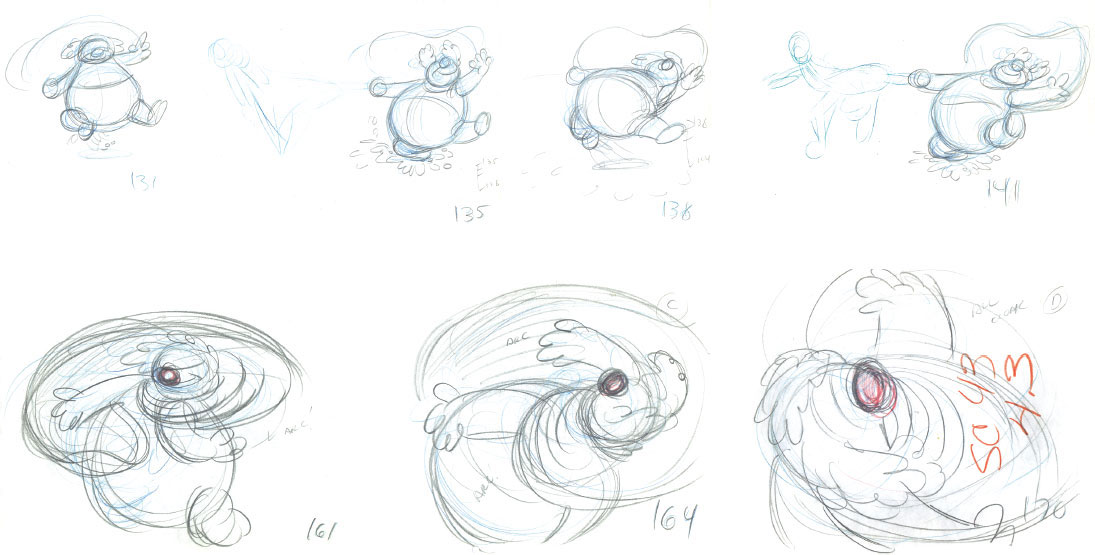

1950

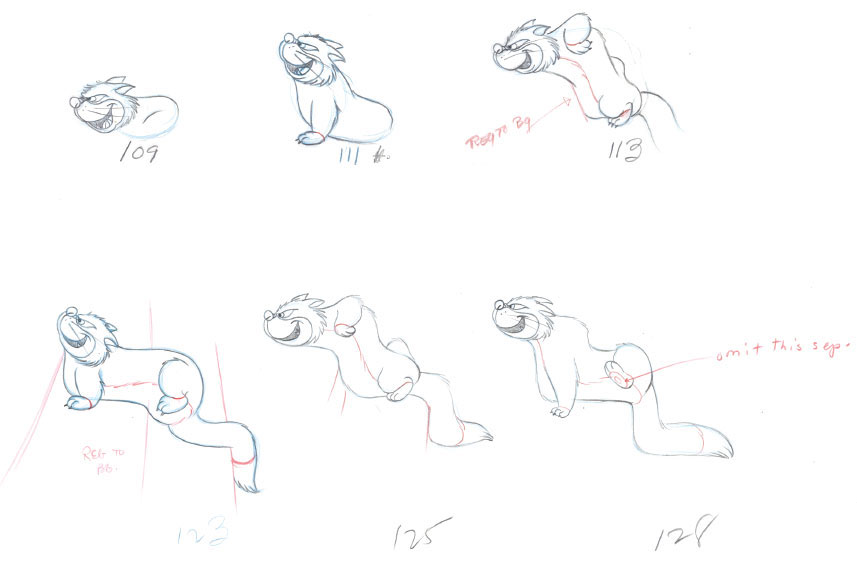

LUCIFER

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 1.6, Sc. 63

In an effort to portray Lucifer not only as evil, but also as an eerie and bizarre character, Kimball invented this sneaky motion as the cat follows Cinderella up the stairs. At this moment his attention is on a mouse which is hiding under one of the tea cups placed on the tray Cinderella is carrying. This quick feline movement is completely illogical, as Lucifer’s body stays low to the ground and conforms to the shape of the steps, creating a zigzag move. There is a confident, but also deviant quality to the scene. Lucifer believes that if he stays determined in his pursuit, it will only be a matter of time before that mouse becomes a snack.

© Disney

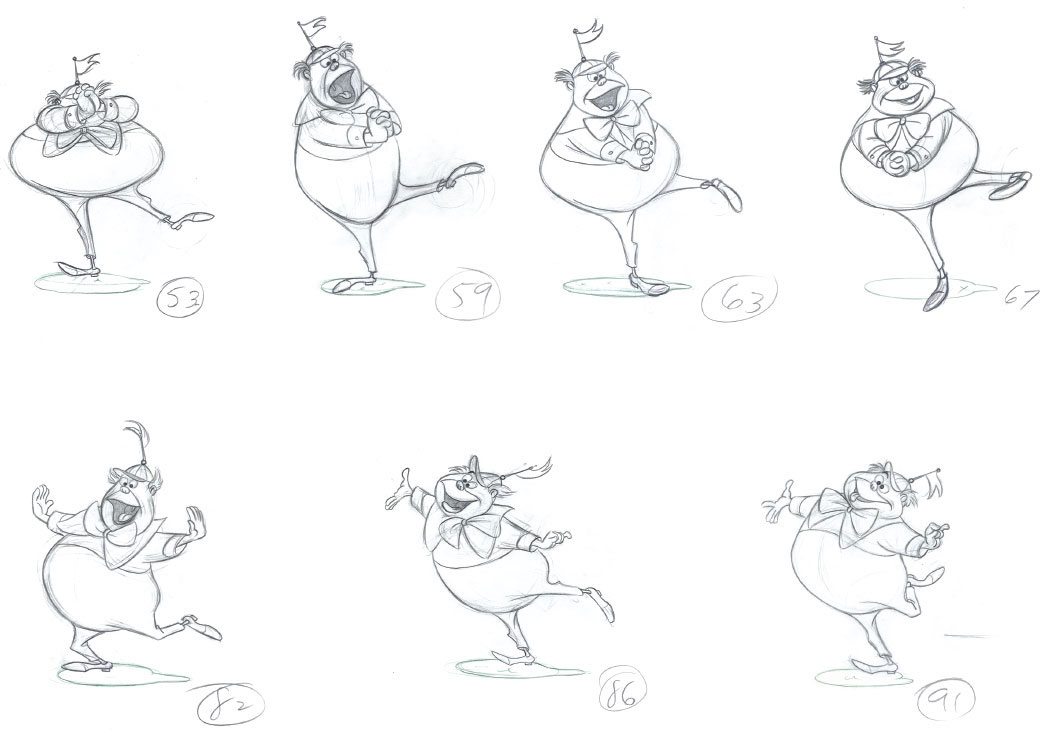

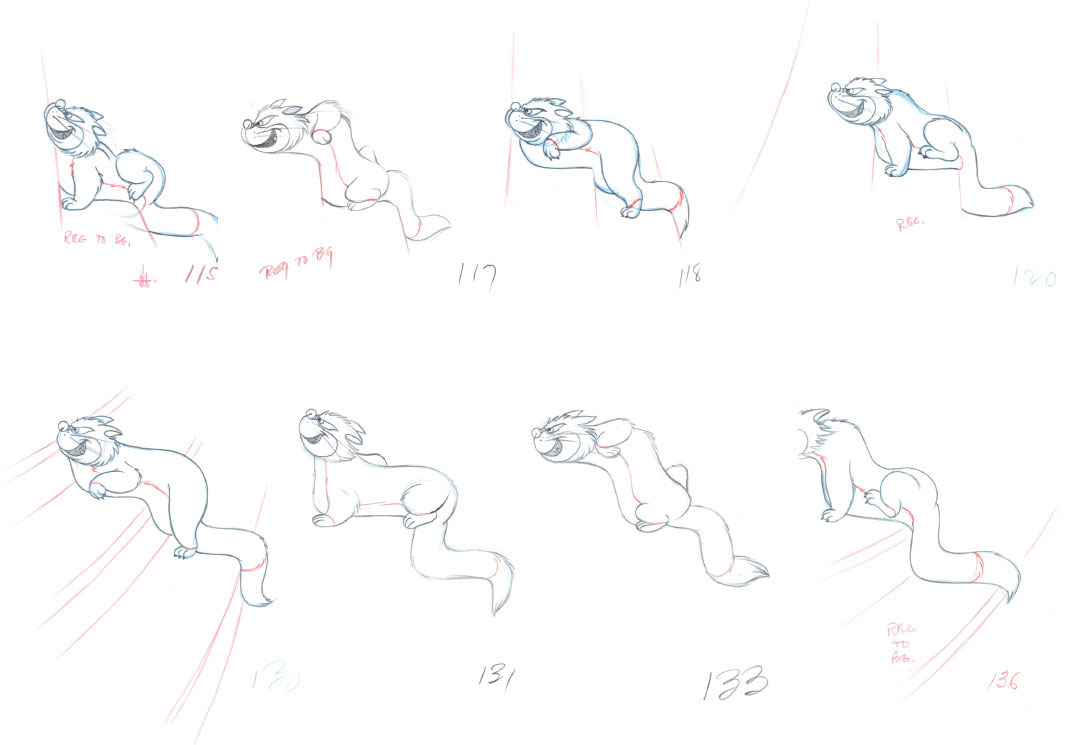

1951

TWEEDLEDUM

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 5, Sc. 36

In this scene Tweedledum leaves his buddy Tweedledee offscreen as he starts to recite the story of the Walrus and the Carpenter to a curious Alice.

He sings with a characteristic lisp: “The thun watch shining on the thea, shining with all hith might…” During the line, Kimball moves Tweedledum to the right and then to the left. The body action can be broken up into three segments.

The upper body is involved in various arm gestures, the round belly squashes and stretches slowly throughout, and the legs perform illogical twirling moves. Everything works well together with entertaining results. This unrealistic approach to movement places this character firmly in the surreal world of Wonderland.

© Disney

© Disney