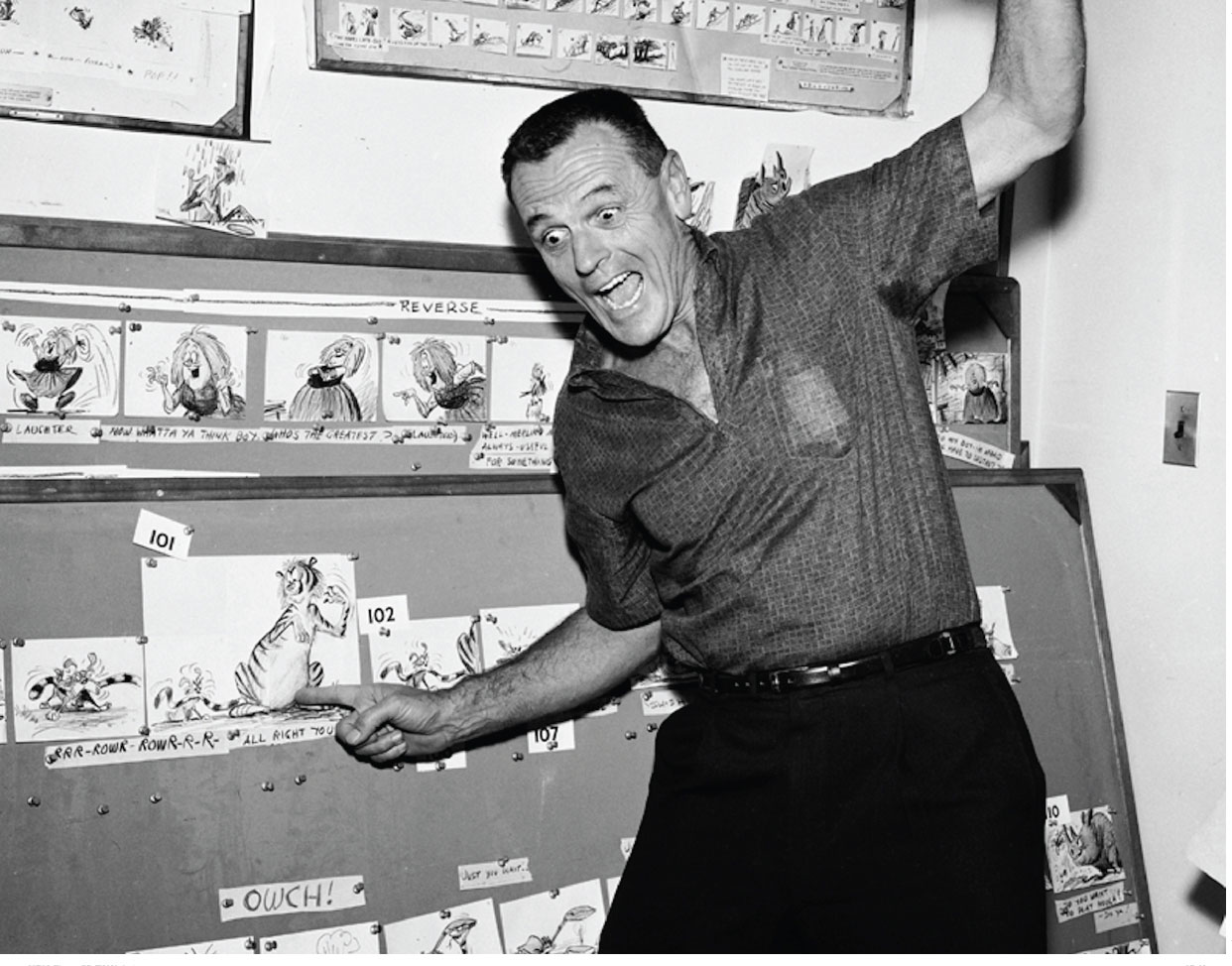

When Walt Disney died in December of 1966, the world wondered what might happen to his animated film productions without Disney’s leadership. The animators and other key personnel were concerned as well. Because of Walt’s unexpected passing, the company was ill-prepared for a traumatic situation like this one. There were those in top management who thought the animation department should be shut down, after all the studio by then had amassed a large number of animated classics that could still generate income through rereleases. Animator/director Wolfgang Reitherman argued strongly for continuing animation, The Jungle Book was half-finished, and a new project called The Aristocats had been approved by Disney to move forward. Fortunately when The Jungle Book was released in October of 1967, it turned out to be a tremendous success and re-established Disney animation as a unique and valuable form of entertainment, loved the world over. Under Reitherman’s leadership, the studio’s group of master animators would produce a few more films until retirement age, but not before training a number of young artists that would help guarantee the future of the art form. Woolie Reitherman, as his colleagues called him, had made the switch from animator to co-director on the 1959 film Sleeping Beauty. At the time of Walt’s death, he served as single director on the studio’s animated features. Naturally his relationship with the other animators changed; formerly he had been a co-worker, now he was their boss. But this new arrangement worked (for the most part), because Woolie always insisted on teamwork, he had enormous respect for the talent in the department and key animators were included in important decisions regarding story and character development.

Throughout his life, Reitherman had been an enthusiastic pilot, he loved the feeling of freedom and independence in the cockpit. As a young man he was strong-willed with a zest for life and a sense of adventure. At the advice of an art teacher he applied to Disney and got hired in 1934.

The management at that time must have sensed Woolie’s freewheeling spirit right away, because he was spared spending any time in the in-betweening department at all. Instead he jumped into animation right away and drew simple scenes on short films like Funny Little Bunnies, Two-Gun Mickey, and The Band Concert. Woolie stated later that he would not have survived the tedious assistant program for newcomers to the studio.

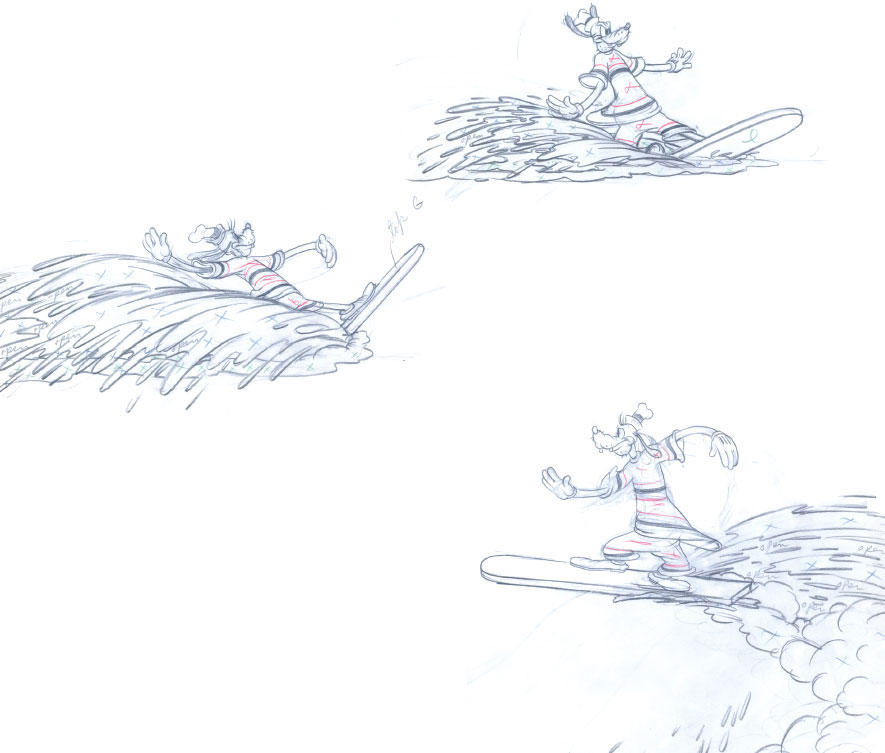

He was ready to take this new medium of animation straight on. Other short film assignments followed, and when Reitherman animated a few outstanding personality scenes with the character of Goofy for Hawaiian Holiday, his colleagues took notice. Just about every possible surfing mishap is shown here, with Goofy facing the additional challenge of trying to surf a wave that has a personality and doesn’t like surfers. Timing is all-important in animated situations like these. Pauses within the action give the audience time to take in a gag and have a laugh.

Woolie’s work on Hawaiian Holiday made his colleagues take notice.

© Disney

But Woolie’s first assignment on an animated feature film would not get any laughs from the audience: the Magic Mirror in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs served a purely dramatic purpose. When being asked a question by the evil Queen, he answers her truthfully. The Mirror is neither for nor against the Queen, his responses are delivered in a stern but neutral manner.

After animating a hilarious situation involving Goofy, this character’s handling needed a completely different approach. The technical challenge Woolie faced was to draw the face in perfect symmetry. After several failed attempts, he came up with the idea to draw one half of the Mirror’s face, then fold the paper and trace the other half. It took a lot of precision to give the right amount of life to this art deco face. Too much squash and stretch would have given a humorous, cartoony appearance, but not enough shape-change in the eyes and mouth, and the scenes would have turned out lifeless. After all that careful work, Reitherman was disappointed to see that the final film footage showed his character mostly covered up by fire and smoke effects.

To make the Magic Mirror’s face perfectly symmetrical, Woolie drew one half and then traced the other.

© Disney

Woolie applied a real sense of perspective to Goofy’s animation. An arm motion gets close to camera and is drawn considerably larger to achieve a feeling of dimension and depth.

© Disney

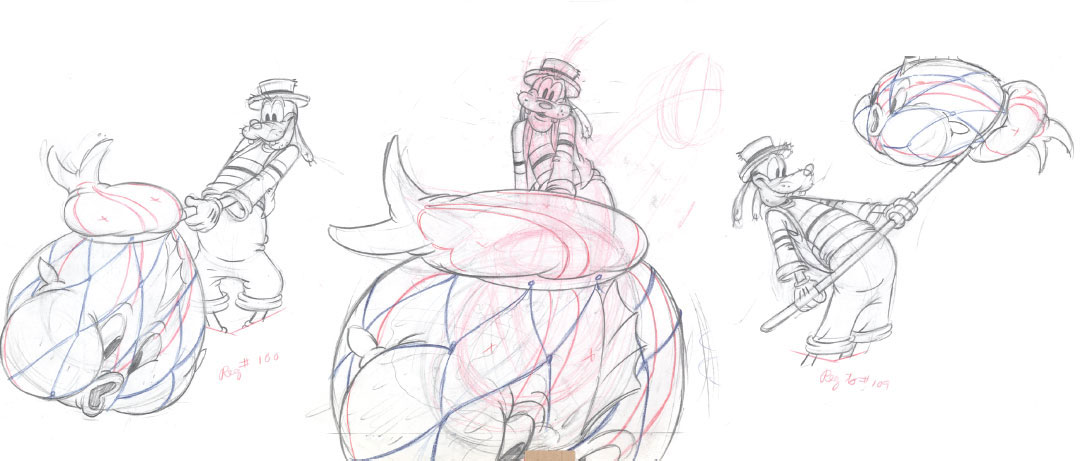

Before work began on Disney’s second animated feature, Woolie had again the opportunity to hone his skills as an animator of comedy. In the 1939 short Goofy and Wilbur his animation is so gutsy and loose, it looks like Reitherman is shaking off any restrictions he had to deal with when animating the Magic Mirror. Goofy goes on a fishing expedition, and uses his grasshopper friend Wilbur as bait. At one point he finds himself in a state of panic when his friend gets swallowed by a fish. The amazing looseness in Goofy’s movements is partly the result of the animator’s use of baggy clothing in secondary action. Sleeves, vest, and pants all hang limp on the character’s body. When he moves, these materials drag and help the overall flow of the animation.

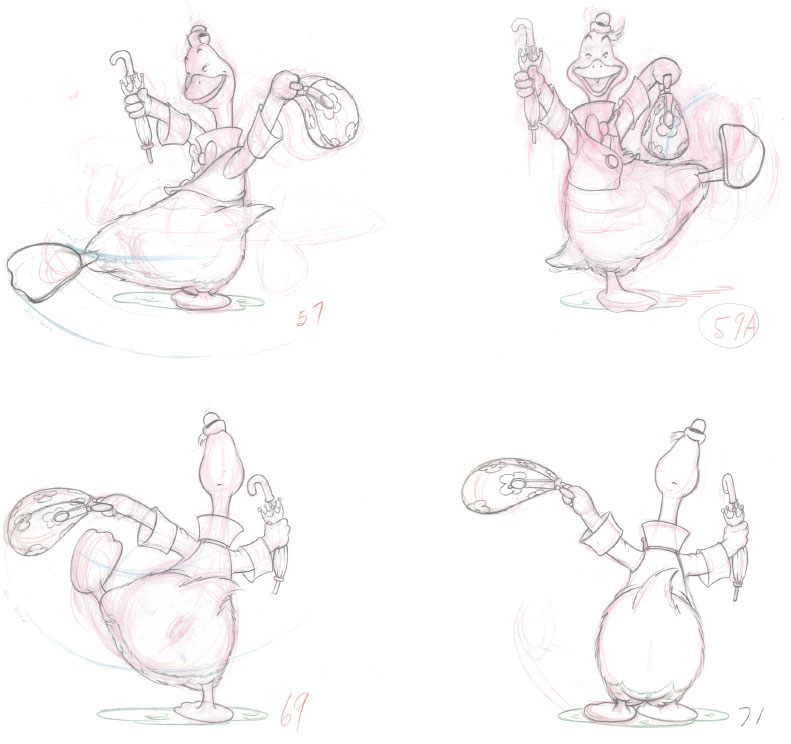

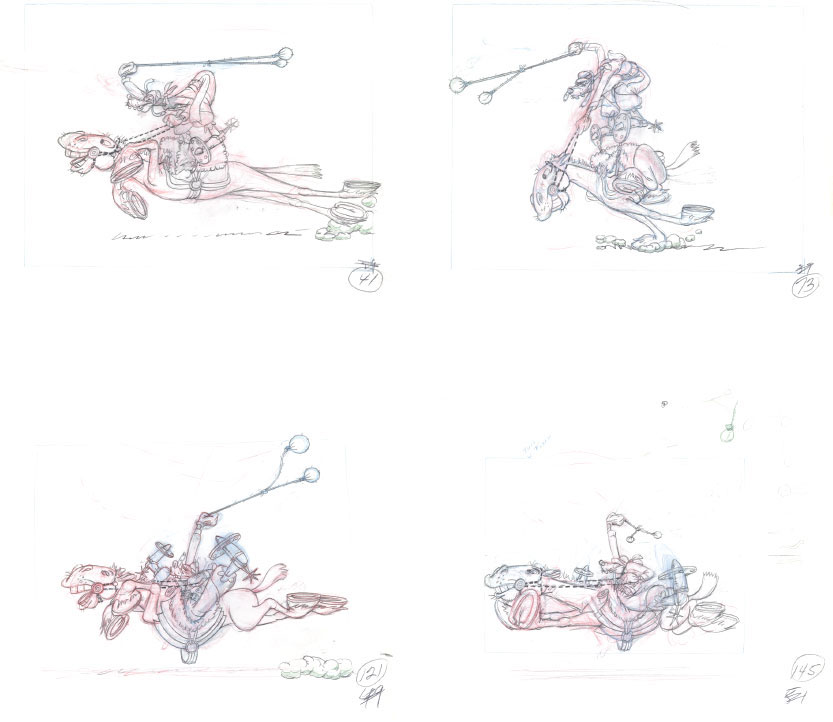

The same year saw the release of the short Donald’s Cousin Gus. Woolie animated the character Gus Goose, who visits Donald and brings along a colossal appetite. The film opens with the arrival of Gus at Donald’s home, and right away his screen presence is utterly captivating. From his unconventional, bouncy walk to the way he comes to a stop in an off-balanced pose, this character’s pantomime performance is inventive and entertaining. Woolie again drew certain moves using exaggerated perspective, as Gus makes a sweeping turn to face the entrance of Donald’s home. First one of his feet gets close to camera, followed by his arm holding a travel bag. This whole rotation adds believability as well as comedy to the performance.

Cousin Gus comes to life through Reitherman’s unique ideas for comical acting.

© Disney

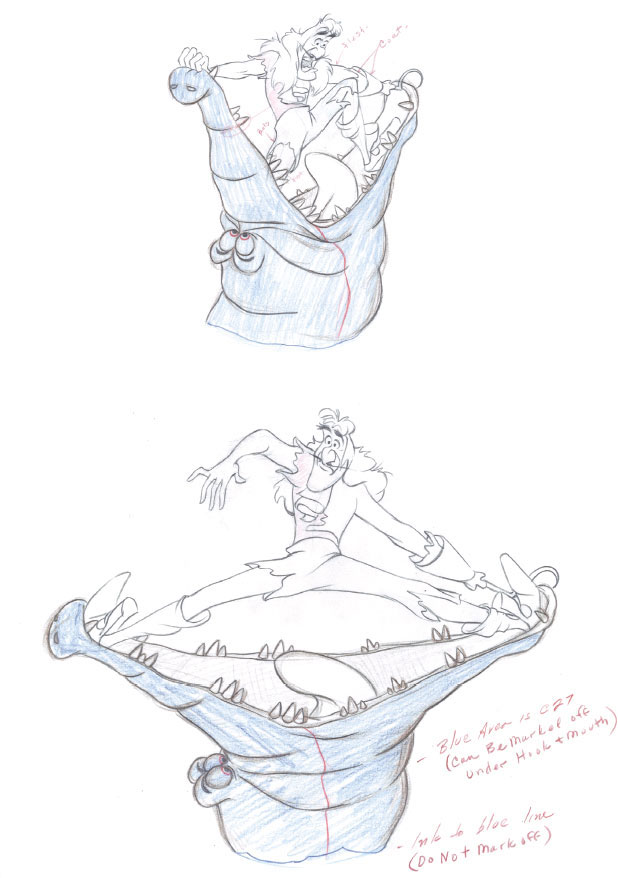

Woolie proved that he had become an animator with great versatility, when he began work on Monstro, the whale for the feature Pinocchio. His talent for funny personality animation needed to be put aside, this character was a true monster who would not only terrify Pinocchio and Geppetto but audiences as well. He was also the climax of the film, and much excitement and fear needed to be developed in order to contrast the emotions of the happy ending that followed.

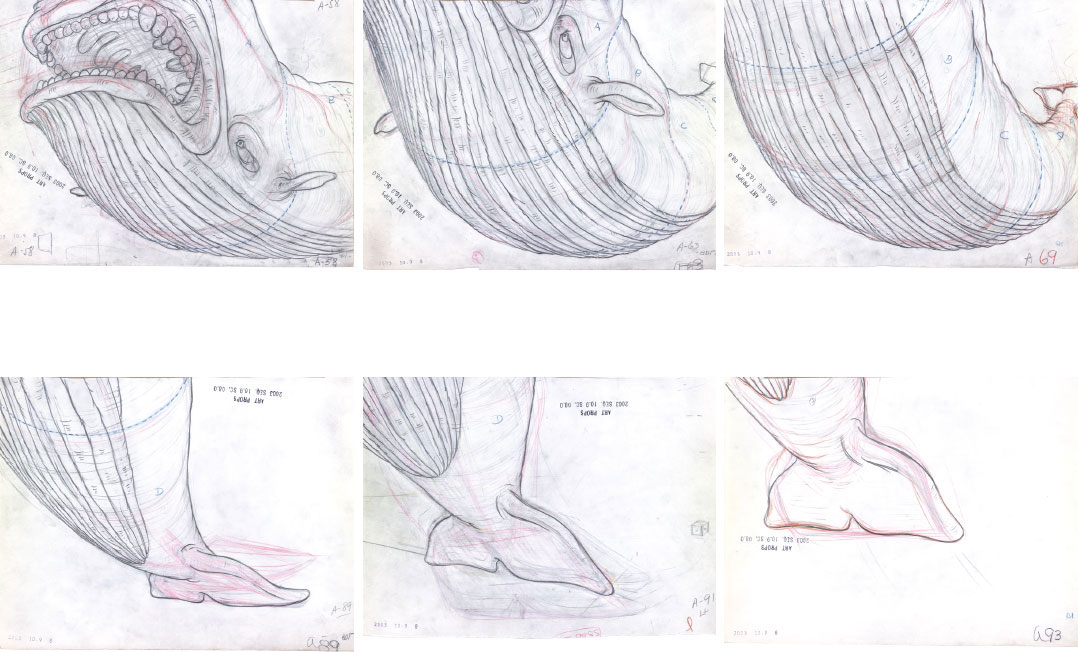

Monstro presented many drawing and animation challenges. How can this creature that has the square shape of an oversized school bus be brought to life? What kind of a motion range should he have? Woolie broke up the whale’s body into three main volumes: head, body, and tail. During dramatic moves—particularly turns—those body parts could be twisted and offset, resulting in dynamic poses and motion. When drawn from low camera angles, Monstro did indeed come across as monstrous. The choice of perspective makes all the difference in such a situation. When looking up at a creature, it becomes instantly imposing and massive looking. Instead, when looking down on to it, the creature seems less frightening, because the viewer is placed at a higher, safer level. While Monstro’s overall body shape looks fairly simple, Reitherman added detail wherever possible. The whale’s fleshy mouth with its countless teeth as well as the definition of his whole underside helped to give the illusion of scale. Staging became critically important.

Reitherman captures the enormous scale of Monstro.

© Disney

Certain scenes showed the entire body, while others were framed closer, so that other characters could fit into the frame. The pacing of the sequence’s editing had to keep building up to the final two scenes in which Monstro leaps right into camera before crashing into rocks on the shoreline. No other action/chase sequence in Disney animation compares to the high drama of this spectacle at sea.

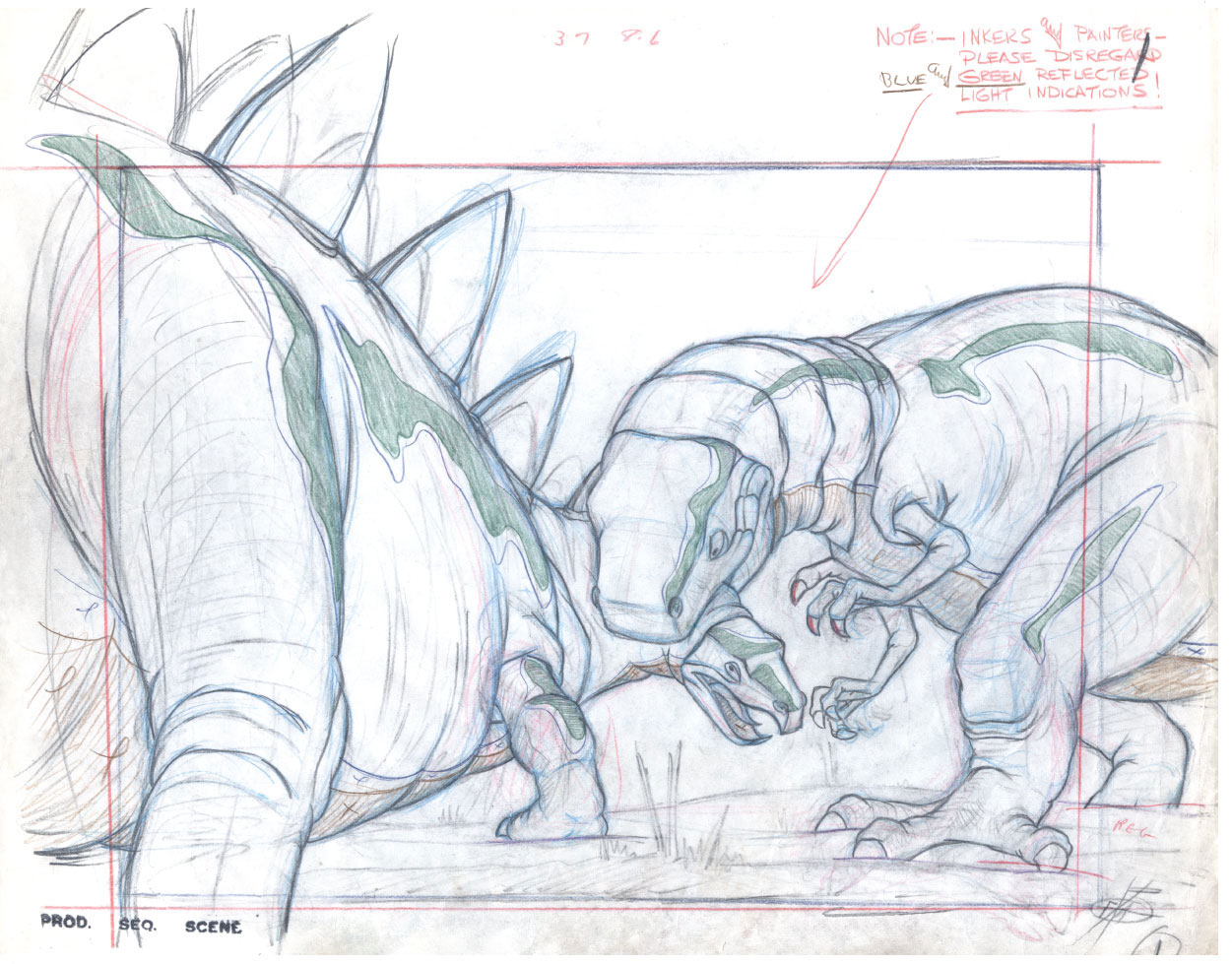

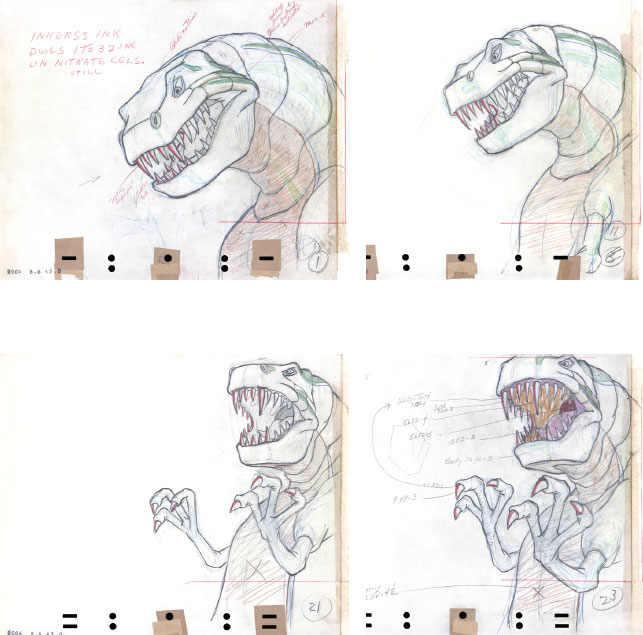

Scale and size were most definitely a major consideration in Woolie’s next assignment for animating the epic battle of a Tyrannosaurus Rex and a Stegosaur in Fantasia’s “Rite of Spring” sequence. Stravinsky’s music set the tone for this ferocious fight to the death. The problem was, how do you bring to life creatures that are extinct? What kind of research would tell you how they might have moved? The place to study prehistoric creatures like these was the Los Angeles National History Museum. Skeletons of dinosaurs gave Reitherman useful information about how the ancient animals were built on the inside. How this knowledge would translate into graphic motion became the animator’s judgment call. Woolie realized that a T-Rex could not possibly have fought using his small arms, instead his enormous teeth were his main weapon. During a walk, the gigantic legs—carrying all that weight—would make the ground shudder on contact. The Stegosaur by contrast had short legs and could only take small steps, as he tried to back away from the aggressor. It took tremendous analysis to achieve natural-looking movements for this monumental fight. On top of that, the animation needed to be in sync with the intense music. On scenes like these, Woolie usually started by putting intuitive scribbles on paper that showed initial compositions and forces. He would then rework and refine those sketches several times over, until he saw believable action that represented what he was aiming for. Fellow animator Ollie Johnston once stated that Woolie sent out more tests to be photographed for a given scene than anybody else. Just like a sculptor, he felt the character’s raw forms first, before any details were added.

FACING PAGE By blocking in the dinosaurs’ anatomy, Woolie gained control over their colossal body masses and perspective.

© Disney

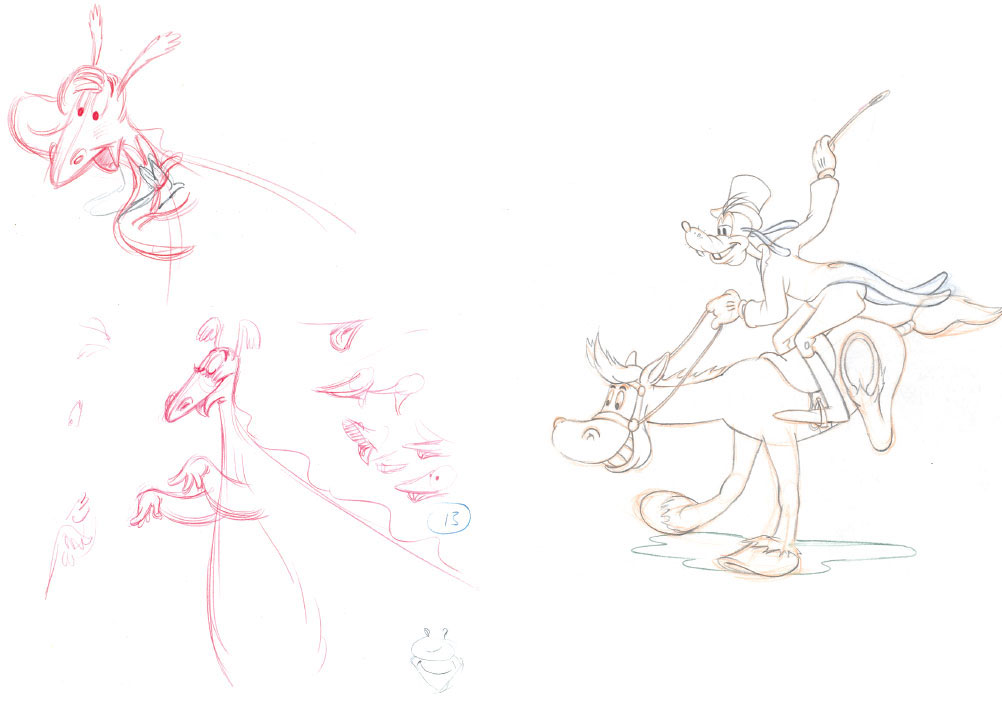

It is astonishing to witness Reitherman’s ability to switch from very dramatic animation like the “Rite of Spring” to hilarious character acting like The Reluctant Dragon. He animated the dragon’s opening scenes as he meets the boy from the village. His performance is over-the-top, flamboyant, and very entertaining. We know right away that this dragon is not the fighting type, he prefers writing poetry. What is so surprising is that Woolie’s superb animation fits in seamlessly with Ward Kimball’s wacky concept for the character. Two animators with different backgrounds and sensibilities come together and create one of the funniest Disney characters. Reitherman also animated on another section of the film, featuring Goofy in How to Ride a Horse. This was natural casting because of his earlier experiences with the character.

Woolie’s talents range from realistic drama to outrageous comedy.

© Disney

There was one type of personality Woolie had not tried to animate yet. Sweet sympathetic characters were usually handed to animators like Ollie Johnston, Frank Thomas, or Fred Moore.

But for some reason, important introductory scenes of Timothy Mouse in the film Dumbo were assigned to Woolie. After watching the little pachyderm being rejected by other circus elephants, the mouse decides to investigate the situation and tries to befriend Dumbo, who is hiding in a haystack. We find out that Timothy is quite the psychiatrist, because after a short talk, during which he introduces himself as a friend, the elephant comes out of hiding to meet the friendly rodent. Timothy is an anthropomorphic mouse, he wears clothes, walks on two legs, and gestures like a human. What is interesting to see is that he maintains mouse-like qualities. Woolie’s animation shows quick moves and appealing poses that communicate what sort of character he is: a buddy, who is there for you. His walk needed to be established in this early section of the film. At one point Timothy turns away from Dumbo in order to fake a momentary disinterest in the elephant’s problem. The movement of his little legs have just the right amount of rotation so that an audience believes, if a mouse could walk on two legs, this is what it would look like.

A mouse that walks like a human looking like a mouse.

© Disney

The chase sequence in The Legend of Sleepy Hollow had dramatic action, interspersed with pauses for the audience to catch their breath.

© Disney

After Dumbo was finished, Disney was no longer able to continue feature-length productions. Pinocchio and Fantasia had not generated profits during their original releases, while overseas markets were cut off because of the war. The studio managed to stay afloat by turning out propaganda and other short films. Woolie contributed beautiful animation to films like El Gaucho Goofy, How to Swim and How to Fish. But for the next few years he left the studio to fly for the United States Air Force. Woolie would not return to Disney until April 1947. The studio had begun work on two featurette films The Wind in the Willows and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

The latter included a dramatic chase sequence that involved the frightening Headless Horseman in pursuit of the main character Ichabod Crane. Woolie was back in his element as an animator of exciting action scenes. On Halloween night, Ichabod rides home after attending a party. The sounds of the forest become more and more daunting when, out of nowhere, the Headless Horseman appears with only one thing in mind, to cut off Ichabod’s head with his sword. There are occasional comedic moments during the sequence (Ichabod’s horse is clumsy and as frightened as his rider), but for the most part this chase is exhilarating and relentless. Woolie strongly believed in pacing an action sequence a certain way. He stated that during fast-paced action scenes there needs to be pauses where things slow down. This would give viewers the chance to catch their breath before tension rises again and speed is accelerated again. The Headless Horseman’s steed takes a big leap into the air, which slows down the running pattern. Horse and rider then land downhill and pick up the pursuit. Another pause in the action occurs when Ichabod hangs on to the neck of his galloping horse. He is smiling and petting the horse’s head, because he believes the danger has passed. Moments like these help to give texture to a volatile sequence.

Exciting material kept coming Woolie’s way. For the film Cinderella he animated the climactic scenes with the mice Gus and Jaq, as they try to deliver a key to Cinderella, who has been locked up in her room. The task seems overwhelming because they need to pull the key up an extremely high staircase. Tension is increased by the cat, Lucifer, who interferes with the mission of the brave mice. At any given moment during the sequence the chance of making it all the way to the top of the tower seems impossible. The filmmakers cut back and forth to a different situation downstairs, where the Grand Duke is visiting with the stepsisters and Lady Tremaine, who is unaware of the missing key. Editing, pacing, and a feeling of anxiety make this one of the most suspenseful sequences ever put on film.

Woolie emphasizes the weight of the large key, an almost unmanageable obstacle.

© Disney

Less dramatic but more surreal was Reitherman’s assignment for Alice in Wonderland. He animated the sequence where the White Rabbit unsuccessfully tries to prevent his house from being destroyed by Alice. The girl has magically grown to the size of a giant after entering the cottage. Now her huge arms and legs squeeze through doors and windows, threatening the structure’s foundation. The bizarre storytelling doesn’t prove very captivating, so Woolie focused on establishing contrasts between the involved characters. Alice only wants to regain her actual size, while the nervous lizard tries to follow orders from the bossy dodo, who tells him to go down the chimney to get rid of the human monster. It is hard to get to know those two characters since their appearance in the film is very brief. But the White Rabbit is entertaining and shows consistency in his personality. During all the commotion around his house, he keeps pointing at his watch, afraid of being too late. We never find out what for.

The White Rabbit is in constant fear of being late.

© Disney

Woolie found much more satisfaction animating scenes with Captain Hook for the next film, Peter Pan. His colleague Frank Thomas supervised the animation of the character, but was unable to draw every single scene with him. It was decided that Reitherman had the perfect experience to handle an action sequence that included the encounter between Captain Hook and the Crocodile. Applying broad action combined with brilliant comedy, Woolie turned this sequence into the most thrilling section of the film. Nothing seemed to be off limits. The Crocodile swallows the Captain whole, before he re-emerges intact. During a tense moment, Hook tries to prevent being eaten by standing at the edge of the creature’s mouth, holding it open with all his might. Those scenes raised a few eyebrows at the studio; after all, such cartoony situations had previously been reserved for a character like Goofy. Woolie did not care; he had too much fun making the impossible come off as believable. Audiences turned out to be on his side; they bought the bizarre animation, because it was entertaining. And what kept it from looking like a Goofy short was the fact that Woolie always drew Hook with accurate human anatomy. This broad sequence actually added to the range of Hook’s personality. He is definitely a menace to Peter Pan, but in this instance he almost gets consumed by an oversized crocodile. Even villains live in fear.

Reitherman said: “Nobody is going to worry about a gag’s logic, if it’s funny.”

© Disney

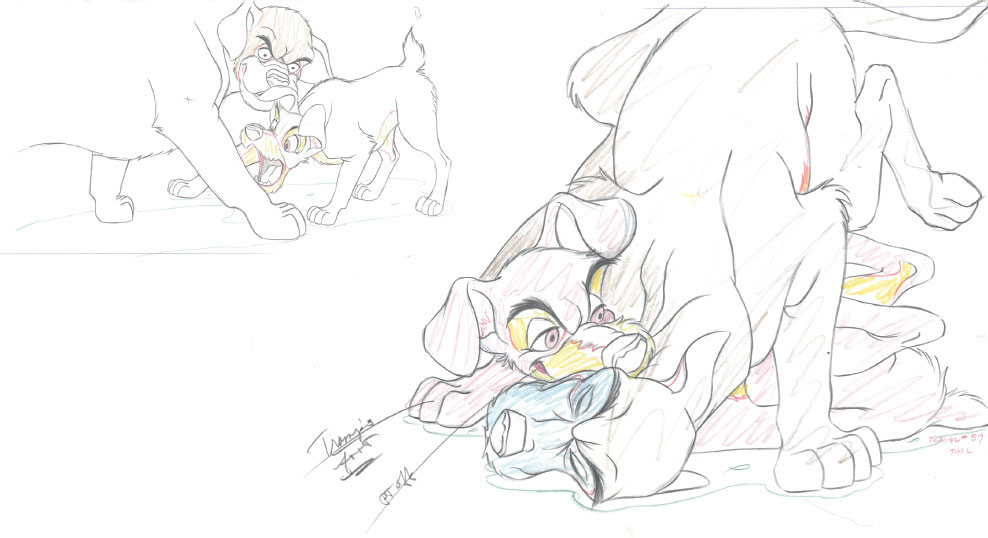

Broad action, but in a solely dramatic way was required for two major sequences in the movie Lady and the Tramp. Woolie’s animation brought thrilling excitement to both sections of the film. After Lady runs away from Aunt Sarah, she is being chased by a pack of street dogs. When they corner her, Tramp comes to the rescue and fights them off. The fact that he is outnumbered makes for an intense situation. Before the fight begins, Tramp stares the dogs down, as he growls in a frozen position. The actual combat doesn’t last very long and is partially staged as shadows. A few fierce close ups of dogs biting add to the feeling of heightened emotion. After the dogs flee, Tramp, out of breath, turns his attention to Lady who had been hiding behind a barrel.

During this fight sequence, realistic drawing was required to make the action believable.

© Disney

Real drama as Tramp fights the rat.

© Disney

Woolie’s other action sequence takes place at the end of the film, when Tramp enters the house to confront a rat that has approached the baby’s cradle. Woolie timed this fight as dramatically as he could. Rat and dog face each other, moving ever so slightly, then in a flash their movements become fast and jerky… and suddenly they freeze again. Tramp ends the confrontation with one quick bite. By now Woolie had become a true master at dramatic action, a role that would continue into the next film.

As mentioned, Reitherman became a sequence director on Sleeping Beauty. His days as an animator were over. Now Woolie would have greater control over certain sections of the film by working closely with story people and layout artists to get the maximum out of a sequence. One of them dealt with the epic confrontation between Prince Phillip and the Dragon. He supervised all of the animation that was done for this dramatic encounter.

“Now shall you deal with me, my prince, and all the powers of hell” are Maleficent’s final words as she transforms herself into a terrifying dragon. It was important for Woolie that the audience believed the beast is going to kill the prince. After a few fire-breathing threats, the pursuit begins and steadily intensifies. Phillip is fighting as he backs away through thorns, up a hill, until there is nowhere to go. Just when it looks like the end for the prince, he throws his sword into the dragon’s heart. Fire effects animation and the intense musical score based on Tchaikovsky help to keep the audience on the edge of their seats throughout the sequence. Unfortunately the film lost money in its initial release, it seems audiences could not warm up to a film this stylized.

Eric Cleworth animated many scenes for the fight under Woolie’s direction.

© Disney

The following film, One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) represented a significant change in Disney storytelling. After the monumental production of the fairy tale Sleeping Beauty, Dalmatians was set in contemporary London. No pixie dust or magic anywhere in sight, this story was about the kidnapping of puppies. Reitherman was one of three co directors, who translated Bill Peet’s storyboard into the first Disney film of the modern era. Gone were the lush, realistically painted backgrounds, making room for a fresh, cutting-edge visual style. One of the sequences Woolie directed was the utterly charming twilight bark. Desperate to let the word out about their puppies’ disappearance, Pongo and Perdita use this canine gossip line to reach other dogs in a call for help. One Hundred and One Dalmatians was made for a fraction of Sleeping Beauty’s cost, the film was enormously successful worldwide, and proved that Disney animated films could be profitable again.

Starting with The Sword in the Stone, Woolie served as solo director. Walt Disney had gotten to a point where he trusted Woolie’s judgment and experience. Since Walt had gotten involved with many other types of entertainment (theme parks, TV) that took much of his time, it was important to him that an artist with natural leadership skills took on his animated productions.

The Sword in the Stone proved fairly unsuccessful with critics as well as audiences, but The Jungle Book broke studio box office records. The tone of the stories being told in Disney films by then was much milder than in Walt’s earlier achievements. Woolie wanted to make films for families, and he became increasingly concerned about scaring children with terrifying villains.

He stated around that time: “If we lose the kids, we’ve lost everything.” Perhaps raising his own children made him change his philosophy for storytelling. What kind of animated films would he want his three sons to see? Films that followed like The Aristocats, Robin Hood, and The Rescuers all had comedic villains and rich character relationships. All of them were successful and laid the foundation for a new generation of animation artists to put their mark on the art form. Woolie Reitherman was not only one of the world’s top animators, he also made sure that Disney animation would continue on into the new century.

1939

GUS

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION OVER ROUGH ANIMATION

Sc. 4

One of Disney’s greatest characters in short films is Gus, a cousin of Donald, who shows up out of the blue with a huge appetite. Woolie sets up this odd, but fun-loving character right from the start as he arrives in front of Donald’s house. The mailbox confirms that he is in the right place, and it’s time to approach the front door behind him. Gus anticipates his little stroll by lifting one foot way up high before swinging it toward the camera, then away from it. As his upper body turns around, the hand holding his travel bag does the same foreshortening motion. Woolie’s animation drawings move within real space. The strong use of squash and stretch during his walk away from the viewer turns this scene into a comical masterpiece.

© Disney

© Disney

1940

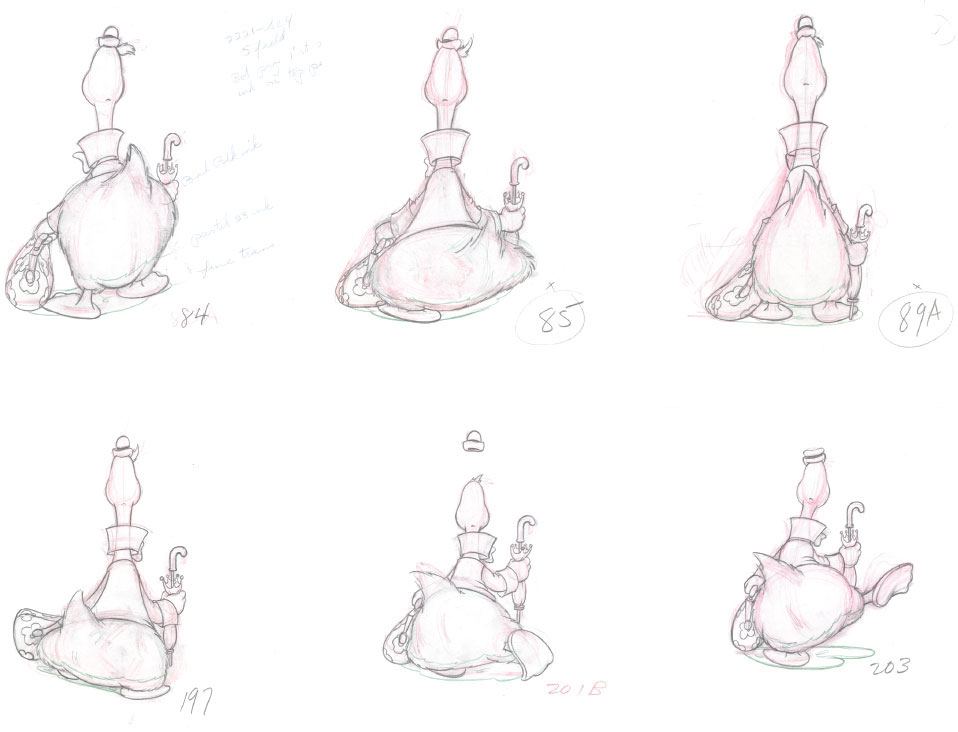

MONSTRO

CLEAN-UP OVER ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 10.9, Sc. 8

Monstro is accelerating his pursuit of the little raft holding Pinocchio, Geppetto, Figaro, and Cleo. He makes a huge turn upward toward the surface by almost brushing the camera. One after the other, each main body part approaches the viewer, first the head with its open mouth, followed by the middle frame and the tail. Woolie effectively animated this move from a low eye-level, which increases the drama and emotion of the scene.

© Disney

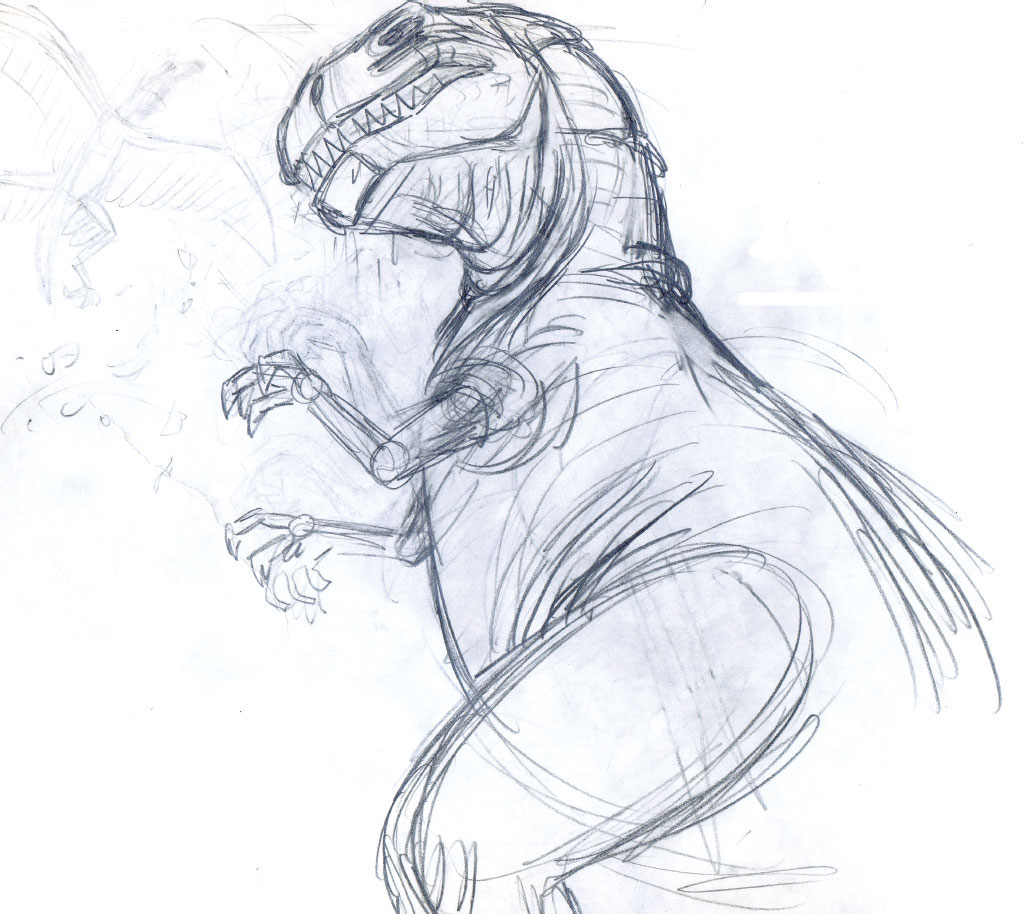

1940

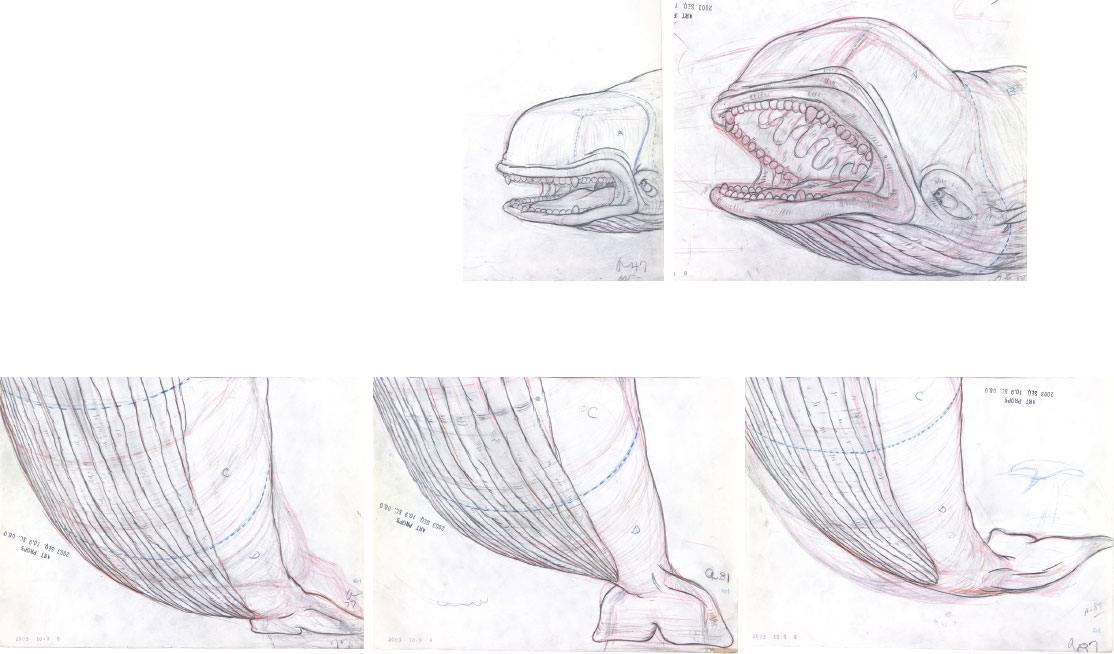

“RITE OF SPRING”

TYRANNOSAURUS REX

CLEAN-UP OVER ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 8.6, Sc. 43

During the “Rite of Spring” section, a horrific Tyrannosaurus Rex is about to lurch toward a Stegosaur. Woolie has the prehistoric monster lean back in anticipation of his leap into the camera. It is important to give a heavy creature like this one plenty of time to change directions, otherwise the animation would lack weight. In this case the T-Rex hovers about ten frames at his high point, before rapidly approaching the camera. There is no better way to frighten an audience than to make it feel that a giant beast is coming down on them.

© Disney

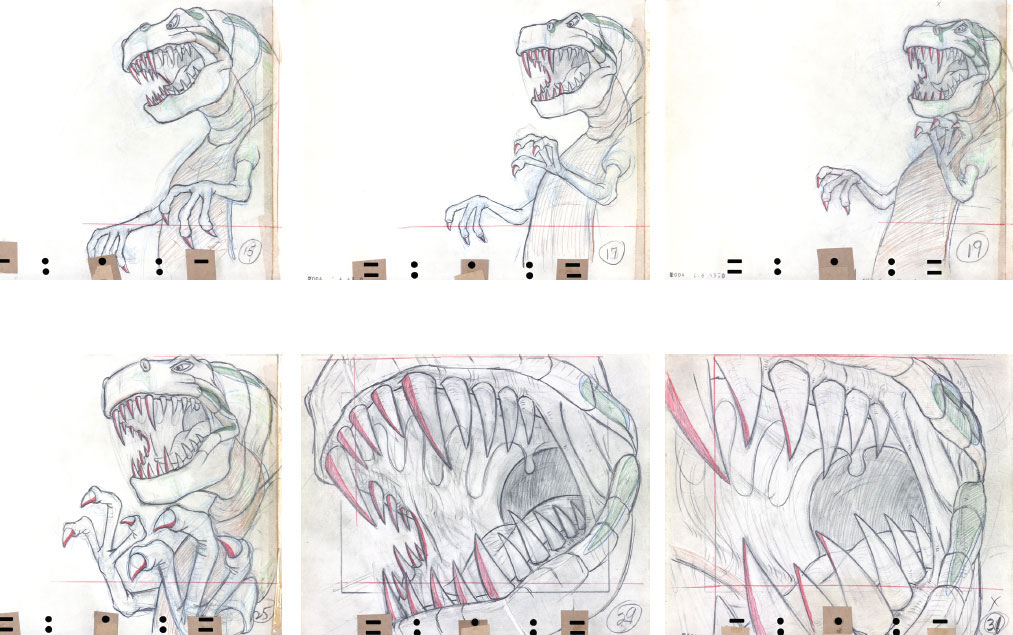

1943

EL GAUCHO GOOFY

GOOFY AND HORSE

CLEAN-UP OVER ROUGH ANIMATION

Sc. 37

In full gaucho outfit, Goofy is riding his horse in pursuit of an ostrich. He seems to be an expert hunter; within seconds he catches the bird. When the film rewinds to the start of the hunt, the scene is shown again, but in extreme slow motion. At this slow speed the audience is supposed to become aware of Goofy’s professional and impressive technique. What we watch instead is a series of hilarious mishaps as Goofy bounces up and down the horse in cartoony fashion before making a painful landing on his own spurs. Woolie exaggerated every piece of action as much as he could, and applied squash and stretch more severely than he normally would, because he knew that it would look funny. These highly detailed key drawings required a humongous amount of in-betweens in order to present the action this slowly. Woolie must have worked with the studio’s most patient assistant.

© Disney

© Disney

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad

1949

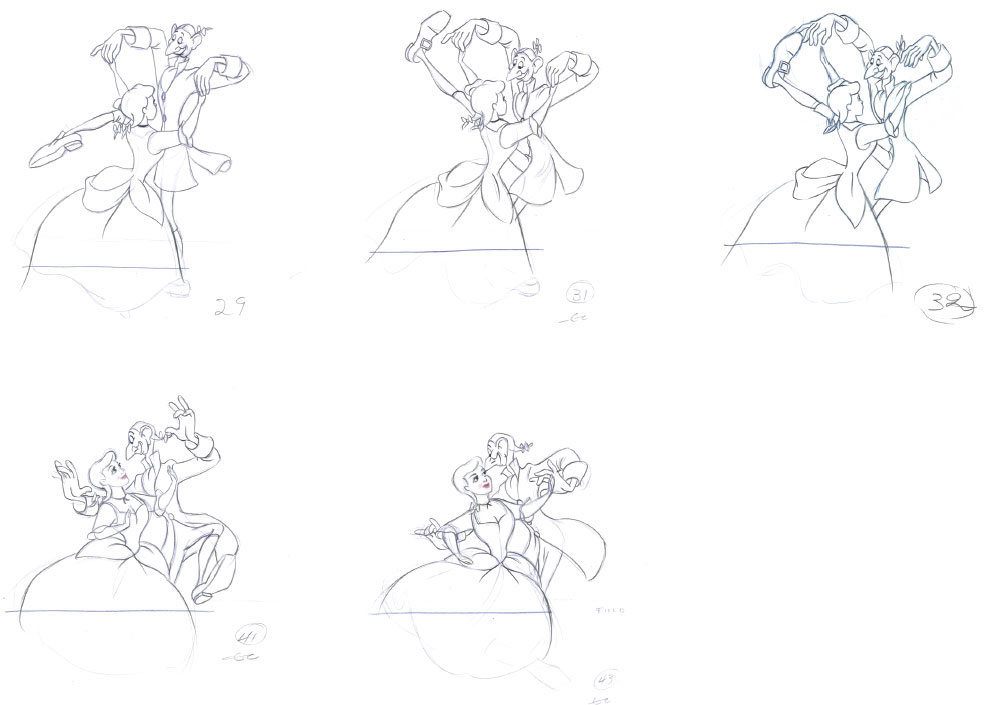

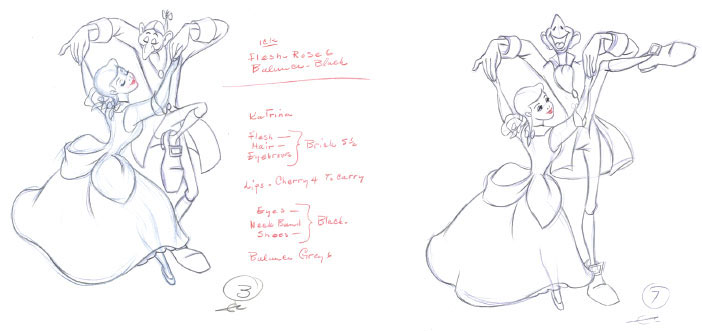

ICHABOD AND KATRINA

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 7, Sc. 21

Ichabod is doing his best to impress Katrina Van Tassel at the party. Woolie’s funny animation of the couple shows them holding relatively still, while Ichabod’s gangly legs keep kicking up out of nowhere. His crazy footwork becomes the center of comedy for the scene. It isn’t until moments later that the characters change into a more conventional dancing pattern. As good as Woolie was handling dramatic material, his comedy scenes rank among the best ever done at the studio.

© Disney

© Disney