When Eric Larson screened the opening sequence from Peter Pan for students in his training program in early 1982, a particular scene caused quite a discussion afterwards. After George Darling unsuccessfully tried to get his children’s attention, he jumps from a seated position high up in the air and onto his feet, before ordering that Nana, the dog, be taken outside where she would spend the nights from now on. It is an unusual and surprisingly broad piece of animation for a character who needed to come across as a believable father to the Darling children, Wendy, John, and Michael. Some of the young animators in the audience that day felt that the jump looked too cartoony, as it reminded them of the type of action Donald Duck would perform. Others thought that the scene greatly enhanced the father’s emotional and extraverted personality. The person who animated George Darling was John Lounsbery, a much-respected artist who was known as a reserved and humble man. Many of his animated characters had eccentric, lively, over-the-top temperaments. They ranged from colorful villains to broad comedic types. John was one of the top draftsmen at the studio, who could adapt to any design style that was required for a particular film. His lines on paper had an energetic quality that expressed how strongly he felt about the characters’ emotions. He was also a patient teacher who took time to go over the work of young animators who often sought his advice and expertise. John often redrew their poses to strengthen the silhouette, or retimed a scene to make it come alive. Many newcomers to the studio would not dare to present a drawing to the unpredictable Milt Kahl, but they knew that John Lounsbery in his quiet way always gave productive advice. Because of his unfortunate early passing in 1976 this underrated, self-deprecating artist never experienced the kind of fame that Walt Disney’s animators encountered after books about their legacy were published, and when documentary films pointed out the men behind the Disney magic. John got hired by Disney in 1935, when the studio was gearing up to produce the enormously ambitious film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. He soon was chosen to assist established animator Norm Ferguson with his animation. “Fergy,” as he was called by his colleagues, had become an expert on animating Mickey Mouse’s dog Pluto.

In the 1934 short film Playful Pluto, Fergy animated the dog trying to free himself from sticky flypaper. At a certain point, Pluto looks directly into camera, allowing the audience to participate in his thought process and decision-making. These animated drawings showed the character thinking, before he took action trying to rid himself of the gluey pest. The scene was an important example to younger animators for proving that mere action wasn’t enough to bring a personality to life; the character had to think in order to become believable to an audience. Fergy animated the scary Witch in the feature Snow White, and Lounsbery studied those scenes carefully as he was doing assistant work on them. After a while, Fergy felt it was time for his student take on his own piece of animation. He handed Lounsbery the scene in which the old Hag goes down a trap door as she cackles gleefully, “Buried alive,” in anticipation of her evil plan to kill Snow White. This wasn’t an easy scene to animate. There is the main downward action, she is addressing her dialogue to the left-behind raven, and her laugh makes her body shiver. This affects the motion of her left arm, which is holding the trap door. Those parts needed to move erratically to complement the Witch’s laugh.

A couple of key drawings show the potential in young John Lounsbery as an animator.

© Disney

After Snow White was completed, John got the chance to animate Pluto in short films such as Society Dog Show and The Pointer. At that time Fergy still supervised those scenes and subsequently influenced the young animator. Lounsbery’s use of strong squash and stretch within loose, bold action was a direct result of his mentor’s tutoring. The two men worked very well together, and by the time production began on Pinocchio, Fergy requested that Lounsbery join the unit that would animate the fox, Honest John, and his partner in crime, the cat Gideon.

Ferguson himself did not animate on the film, instead he served as one of four sequence directors. In this new capacity he helped shape the story material for these two villains.

Several animators were responsible for animating the fox and the cat throughout the film, but Lounsbery drew their introductory scenes. As Pinocchio hops along on his way to school, he catches the eye of Honest John, who is astonished at what he sees: “Look Giddy, look! It’s amazing, a live puppet without strings.”

Honest John and Gideon have their eyes set on Pinocchio.

© Disney

These two crafty, contrasting characters needed to perform with theatrical showmanship. Often the fox becomes an actor as he tries to persuade Pinocchio to forget about school and join show business instead. He is trying to be convincing, and his poses are grand and over the top. The cat usually agrees with whatever the fox is saying, even though more often than not Gideon doesn’t have a clue what’s going on. As they interact with Pinocchio they form an irresistible trio, and the most bewildered misunderstandings become highly entertaining. When working with campy, exaggerated poses, it is of utmost importance that they read clearly to the viewer. The essence of a thought or mood must be found, which always requires a good silhouette within a pose. The way the character gets in and out of such a pose becomes an important factor for a successful performance as well. Usually the timing between held poses is quick and smooth. Lounsbery had learned these principles from studying Fergy’s work and applied that knowledge to great advantage. As far as good draftsmanship was concerned, he would soon surpass his mentor.

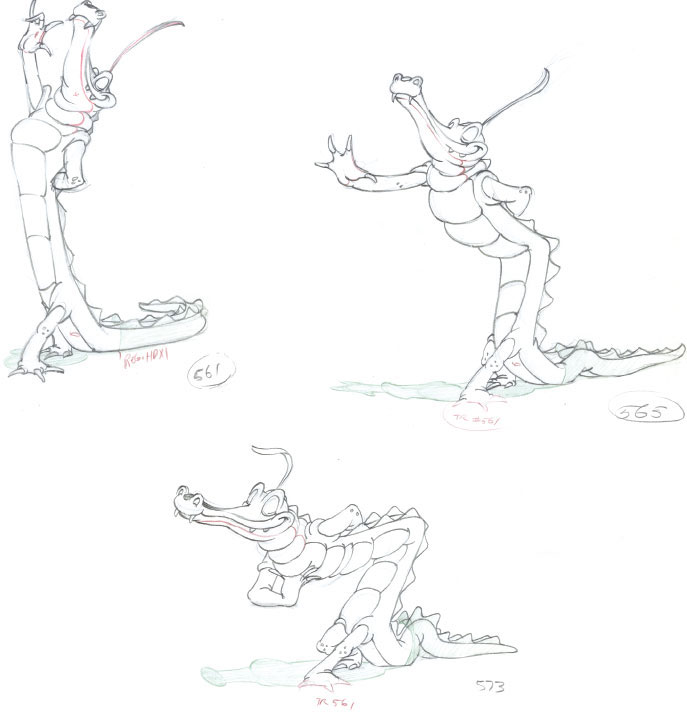

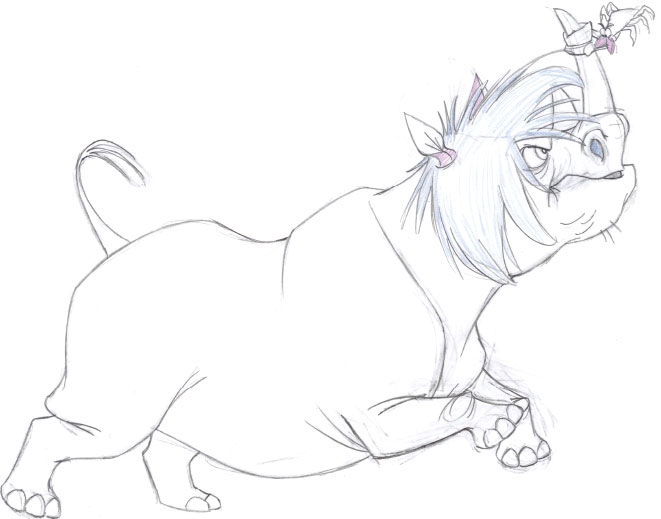

Fergy and Lounsbery worked together again on Fantasia’s “Dance of the Hours” section. Ferguson co-directed the sequence, and John was put in charge of developing the personality of Ben Ali Gator, who becomes love-struck with his dance partner, Hyacinth Hippo. This hilarious relationship offered a number of truly memorable character moments. There are 12 ballet-dancing alligators, but only Ben Ali stands out as a definitive personality. As the gators surround the sleeping hippo, he shows up late, way up high on the columns. Lounsbery animated his entrance with a silly walk, followed by a fluster of arm gestures as he discovers the sleeping “beauty” below. From that moment on nothing can stop him from pursuing the object of his affection. His eyes flutter in adoration, and he places his hands over his heart. Hyacinth awakens and takes off, but her body language says “Come and get me!” After a hilarious pas de deux, an energetic chase ensues, and eventually the other gators, hippos, and other animals get involved.

Lounsbery animated Ben Ali as a professional dancer. Gone are the goofy moves from his early scenes, for the rest of the sequence he dances with style and grace. His relatively skinny body bends and turns in the most unexpected ways, but always ending up in a flamboyant, theatrical pose. This is the work of a star animator, who impresses with technical expertise, musicality, and outstanding draftsmanship. Lounsbery stated in an interview how much he enjoyed getting all the gator’s dance business across, in sync to the beat of Ponchielli’s music.

Ben Ali Gator has all the style of a professional dancer.

© Disney

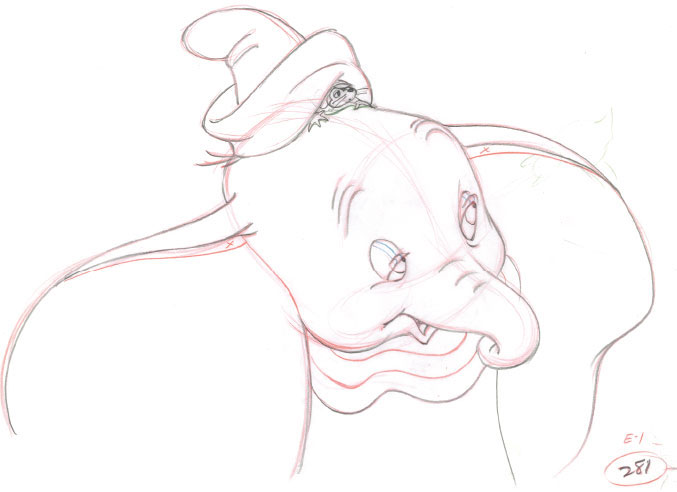

Dumbo experiences the effects of champagne.

© Disney

Every great animator has a range; he is able to take on a number of different character assignments. Lounsbery had shown that he had a feel for exaggerated, vaudevillian types, but his next role would demand a whole different set of emotions. John was promoted to supervising animator on the movie Dumbo, where he ended up working on the title character, along with several other animators. One of the sections he worked on takes place after Timothy, the mouse, and Dumbo return from a visit to Dumbo’s imprisoned mother. The little elephant’s walk feels heavy, and a few tears are rolling down his cheeks. Timothy tries to cheer up his friend, who so unjustly got separated from his mother. Suddenly Dumbo gets the hiccups. These beautifully animated bursts add some lighthearted comedy in this overall sad situation. With each hiccup, Dumbo’s head jolts abruptly while his trunk and large ears are animated in overlapping action. But it is the expressions Lounsbery draws that make these scenes so charming. Dumbo’s eyes open wide in surprise before settling. Timothy suggests that drinking some water will help the elephant’s condition, but by accident Dumbo ends up sipping champagne instead. The hiccups continue, and his expressions become more and more hilarious. Lounsbery injects so much appeal into these scenes; as a matter of fact, he probably drew the character better and with more charm than the rest of the animators. As the story continues, Dumbo starts producing large champagne bubbles, which leads into the famous “Pink Elephants on Parade” sequence.

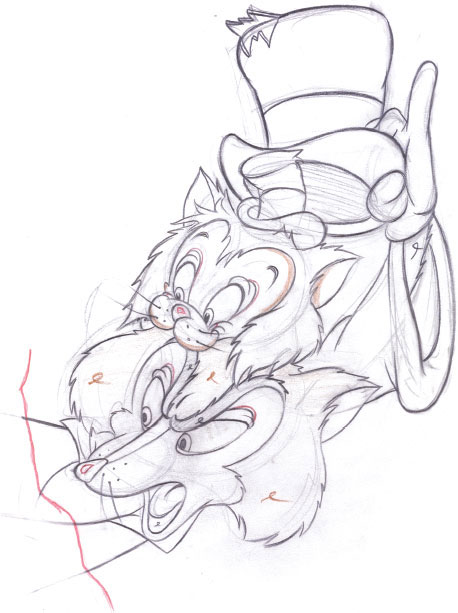

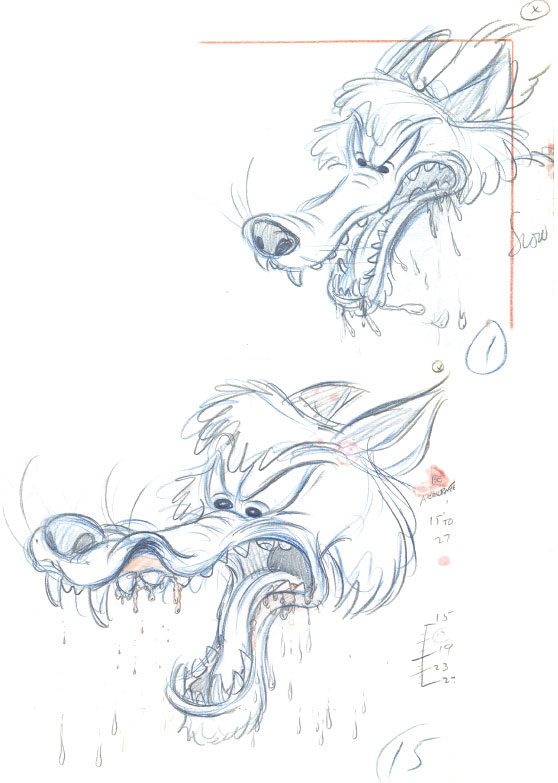

Like most animators at Disney, during the Second World War, John Lounsbery was cast on propaganda films like Victory through Air Power and Chicken Little. The postwar feature Make Mine Music included the short film Peter and the Wolf. John was in charge of developing the frightening Wolf. The character’s appearance is cartoony, as is the rest of the cast, but there is no doubt that this is a vicious creature, who presents a great danger to Peter and his friends. Some of the Wolf’s close-ups are very effective in showing this villain’s bad intentions.

Enormous teeth and drooling saliva enhance the Wolf’s horrifying personality.

© Disney

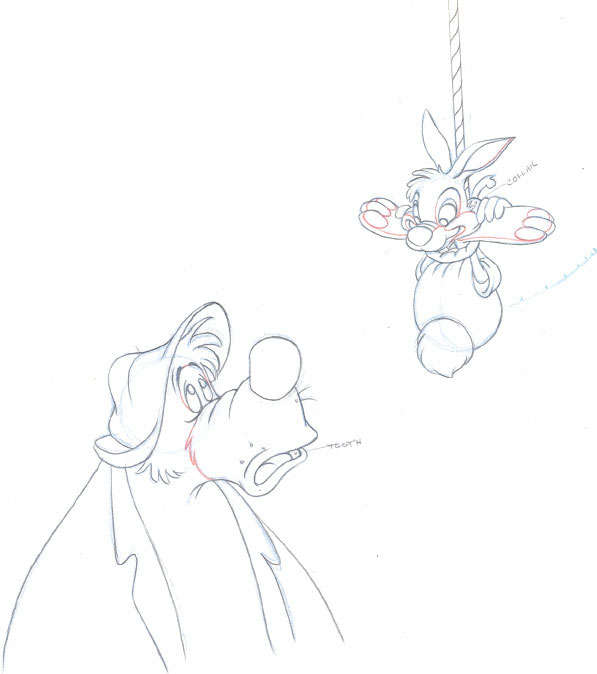

The animal characters in Song of the South were played for comedy, even though Brer Fox and Brer Bear could be a threat to little Brer Rabbit. Like everybody involved with this film, John enjoyed working with these eccentric characters very much. Among other scenes, he animated the section following the capture of Brer Rabbit in a sapling trap. The bear comes along and inquires about the nature of this odd situation, when the clever rabbit convinces him to take his place as a kind of a scarecrow. The contrast between these personalities offered John unique ways of timing the characters’ acting patterns. The rabbit is quick and energetic, while the bear moves very slowly.

Brer Rabbit persuades Brer Bear to take on his job.

© Disney

John’s next character required startling and unexpected type of movements. Willie the Giant is the villain in the Mickey and the Beanstalk section from the feature Fun and Fancy Free. He has magical powers that allow him to turn himself into any type of creature. During his opening song he comes across as a jolly, almost likeable giant, until he discovers Mickey, Donald, and Goofy. He locks them up in a box, except Mickey, who narrowly escapes, but only to find himself trapped in the Giant’s shirt pocket next to an oversized snuffbox. In reaction to the snuff, Mickey can’t help but sneeze out loud. The tobacco reaches the Giant’s nose, and he immediately reacts with several abrupt inhales. Just when the audience anticipates a giant size sneeze, John instead animates the silliest reaction. Willie’s face goes through a couple of quick distortions as we hear a funny, little twang. The scene always gets a big laugh from the audience, because no giant is supposed to sneeze like this.

A not so giant-size sneeze from Willie.

© Disney

After Fun and Fancy Free, Walt Disney was not quite ready yet to restart producing feature-length films, the war had severely interrupted the studio’s flow of income. Instead a few more so-called package films followed. These full-length movies each contained a number of short subjects, which were fairly inexpensive to make. John worked on several scenes for Melody Time and The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, before joining the team of animators that would finally re-establish the full-length Disney animated feature film with the story of Cinderella. The film’s cast of characters ranged from realistic to cartoony in concept and design. Lounsbery steered away from subtle human personalities; instead he animated a number of broad, expressive characters. When the mice Jaq and Gus try to locate clothing items that would be useful for creating a party dress for Cinderella, they run into Lucifer, who is asleep on a footstool. An outrageous sequence begins in which they outwit the cat repeatedly, and sneak a roll of fabric and a bead necklace by the evil feline. This section of the film was directed by Wilfred Jackson, who worked very closely with John on the timing and the suspense of certain moments. The audience is led to believe that eventually the cat, who is not stupid, will outsmart and catch the mice, but instead Jaq and Gus do succeed, barely. The animation is flawless. The quick, erratic movements of the mice are contrasted by the heavy, slow-moving cat, who only commits to a chase when he believes the mice are within his reach.

Jaq and Gus need to outsmart Lucifer in order to collect clothing items for Cinderella’s dress.

© Disney

Lounsbery was also responsible for transforming a horse into a coachman and a dog into a footman during the Fairy Godmother sequence. Each animal is magically lifted in the air; they bounce exactly three times, in sync with the lyrics, “bibbidi, bobbidi, boo,” before taking on their human form. These musical and visual rhythms, combined with stunning special effects, give the scene extraordinary beauty. John Lounsbery continued animating non-realistic characters for the film Alice in Wonderland, where zany, oddball types could be found in abundance. He joined a small team of artists who brought the smoking Caterpillar to life. It was John who animated the famous line when he encounters Alice: “Who are you?” With each exhale the smoke forms a letter, in this case: O, R, and U. Lounsbery anticipates each mouth shape very effectively. For example, before his mouth forms an “O” for the word “who” his lips are relaxed, then come forward to illustrate that sound. This makes for smooth and convincing dialogue animation.

Bruno, the dog and Major, the horse begin their magical transformation.

© Disney

“Who are you?”

© Disney

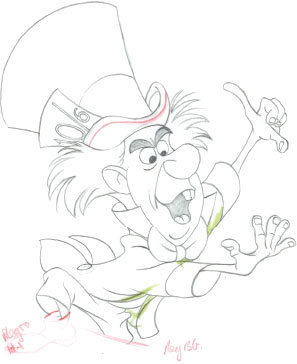

The Mad Hatter explains to Alice what an unbirthday is.

© Disney

Ward Kimball had started work on the Mad Tea Party sequence, but he needed help to finish it. John took on a number of scenes featuring the Mad Hatter. They turned out to look and feel indistinguishable from Kimball’s version of that character. Zany, unpredictable acting came easy to Lounsbery and Kimball couldn’t have found a better collaborator.

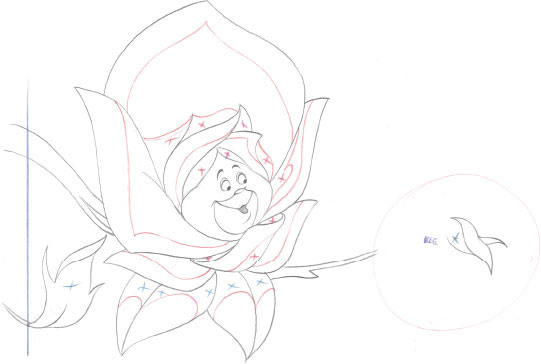

Another character John animated for the film turned out to be more subtle but equally fantastical. The Red Rose conducted a choir of flowers performing the song “All in the Golden Afternoon.” She turned out to be more sympathetic toward Alice and interacted with her without hostility. To bring a flower to life with human characteristics probably sounds like a difficult assignment, but her design already suggested a definite female type. A friendly human face was drawn in the center of the blossom, and twigs and leafs made up her arms and dress. Still, this rose needed to move in a restricted manner. The audience should never assume that she would be able to take a few steps and walk like a human. Motion is limited to her upper body only.

The friendly and sympathetic Red Rose.

© Disney

Disney’s next film, Peter Pan, had an almost all-human cast, with only a few eccentric personalities. One of them was George Darling, a somewhat typical Victorian father who was strict and temperamental, but very much in love with his family. John Lounsbery animated all of his scenes at the beginning of the film. What could have been a secondary character in the hands of a different animator became the comic center of the Darling family. Had he been handled as a realistic, conventional father figure, this family would come across as boring to an audience. But because of Mr. Darling’s frustrations and emotional outbursts we enjoy watching him as well as his interaction with family members. During his first scene he enters the children’s nursery in search of his tuxedo cufflinks. He eventually looks under a bed sheet to instead discover his white shirtfront, with some kind of treasure map drawn all over it. He lifts it up high, expressing horror and disbelief. This is one of many Lounsbery’s scenes, which is very dramatically staged, but because of solid draftsmanship, still fits in with the more realistic characters in the sequence.

Because of his outgoing personality, Mr. Darling becomes the most engaging character in this sequence from Peter Pan.

© Disney

The fact that John also drew scenes with Wendy, Michael, and Captain Hook proves his versatility as an animator. A few wonderful assignments were coming John’s way when production began on Disney’s first widescreen animated film Lady and the Tramp. This wide format presented new challenges, particularly for layout artists and animators. The extended horizontal screen required a much wider representation of environments, while animators needed to fill up the extra space with more characters. In close-up scenes, a single drawing of a dog’s head would often look isolated. One or two other dogs needed to be added in order to present a pleasing composition. All this meant more work, but also additional costs.

Walt Disney was very much aware of Lounsbery’s comedic strengths, and he cast him on Tony and Joe, two lively Italian-Americans who run the restaurant that became the backdrop for the most romantic scene in animation. Tony is the proprietor, a large figure with big gestures that communicate joy as well as anger. Joe is the chef, who is much smaller in size but equally expressive. One scene in particular became a high point that typifies their relationship. When Tramp shows up at the restaurant’s back entrance by himself, Tony orders Joe to bring out some bones for the dog. Then Lady appears from behind a food container. When Joe returns from the kitchen with a bowl of bones, Tony reacts in a volatile manner as he kicks the bowl out of Joe’s hands: “What’sa matter for you, Joe… I break’a your face. Tonight’a butch, hes’a getta the best’a in’a house.” John Lounsbery felt these personalities. His animation shows the same passion that these two characters display. Tony’s wild gesturing comes across as an affectionate satire of Italian articulation. Great acting choices, phenomenal draftsmanship and believable motion make Tony and Joe truly masterfully animated creations. Lounsbery was so attuned to this assignment that he impressed and surprised his fellow animators with his astonishing personality animation.

Tony serenades Lady and Tramp.

© Disney

John also animated key scenes with the English bulldog Bull, who, along with other dogs, befriends Lady in the dog pound. Bull’s facial features are loose and rubbery, which is perfectly appropriate for this type of dog. Every one of his dialogue scenes are a joy to watch, because of unusual mouth configurations, and gutsy overlapping action of cheeks and lips.

Bull’s unusual mouth configuration helped to create entertaining dialogue scenes.

© Disney

When Lady and Tramp try to visit the local zoo in order to seek help from a beaver, they find a policeman guarding the entrance. Tramp engages a passing professor in a fight with the policeman, so he and Lady can slip into the zoo. Lounsbery animated this spirited sequence, which involved physical interaction, since the two characters fought and argued with one another over the issue who this dog (Tramp) belongs to. Strong use of squash and stretch helped to keep this altercation lively and entertaining.

The professor tries unsuccessfully to convince the policeman that he is not Tramp’s owner.

© Disney

King Hubert brandishes an unusual weapon during his disagreement with King Stefan.

© Disney

The shift in style from Lady and the Tramp to Sleeping Beauty was significant in many ways. Disney characters did not appear as dimensional figures, instead flat graphic shapes made up their design. John Lounsbery’s drawing style of King Hubert and King Stefan did not exactly match the sophisticated look Milt Kahl brought to the sequence in which both characters toast to the future of their children. But by the time John’s scenes were cleaned up and traced on to cels, the differences became very minimal. Milt Kahl animated the first half of the sequence, when both kings lift their glasses in friendship. John takes over as an argument develops over the possibility that Prince Phillip and Princess Aurora might not like each other when introduced.

This was smart casting since Kahl excelled at nuanced subtle performances, while Lounsbery preferred outgoing, extraverted acting.

John also enjoyed animating a few close-up scenes featuring the pig-like goon. His face was perfect for broad dialogue shapes and distortions throughout his head.

John’s work on one of Maleficent’s goons.

© Disney

The flat graphic styling of Disney characters continued, as the studio began work on One Hundred and One Dalmatians. By this time Lounsbery had done enough work applying the new approach to drawing that his animation of Cruella’s henchmen Jasper and Horace fit right into the overall look of the film. Live-action reference was filmed for every human character to aid the animators in their animated performances. Yet it is interesting to note that, while Roger and Anita often show traces of live-action in the film, Jasper and Horace’s origins seem to be the animator’s imagination entirely. This speaks for the way John made use of the live-action reference. He was able to take the actors’ ideas for certain scenes, but made considerable changes in order to produce believable drawn personality animation. Lounsbery punched up the timing, he would strengthen the key poses and push the feeling of weight. When Jasper and Horace engage in a conversation with Nanny at the Rad-cliffs’ front door, they pretend to be from the electric company and need access to the home. Their faces are animated with great elasticity as their mood changes from false politeness to sincere annoyance, when Nanny refuses them entry.

Jasper and Horace Badun from One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

© Disney

John also supervised the animation of the Colonel, a befuddled but likeable English sheepdog, who acts as the self-proclaimed leader of the small group of farm animals, that includes the cat Sergeant Tibs and the horse Captain. The Colonel’s eyes are covered by long hair, which presents a challenge to the animator. How can specific expressions be drawn without showing eyes?

John divided the dog’s top hair into two parts and animated them as eyebrows. Together with the flexible mouth unit he was able to draw any attitude that was required during his performances.

The Colonel presented the challenge of how to show expression without visible eyes.

© Disney

On the 1963 film The Sword in the Stone, Lounsbery again followed Milt Kahl’s lead when animating Merlin and Sir Ector. Milt’s draftsmanship proved a challenge to match (especially the way he drew hands), and John’s graphic version of these characters differ slightly, but the performances are solid and believable. When John had the chance to animate a character without Kahl’s input, his animation feels looser and more personal. During the wizards’ duel, Madam Mim changes herself into different animals, including a chicken trying to get to Merlin as a worm, and a rhinoceros who overpowers Merlin as a crab. Mim as a chicken is insanely excited because she thinks she has the upper hand, until Merlin as a walrus falls from the sky on top of her. As a rhino she is confident that her heavy weight will smash Merlin, but the magician turns himself into a goat and kicks Mim down a ledge into the water.

Mim as a chicken…

© Disney

…and as a rhino.

© Disney

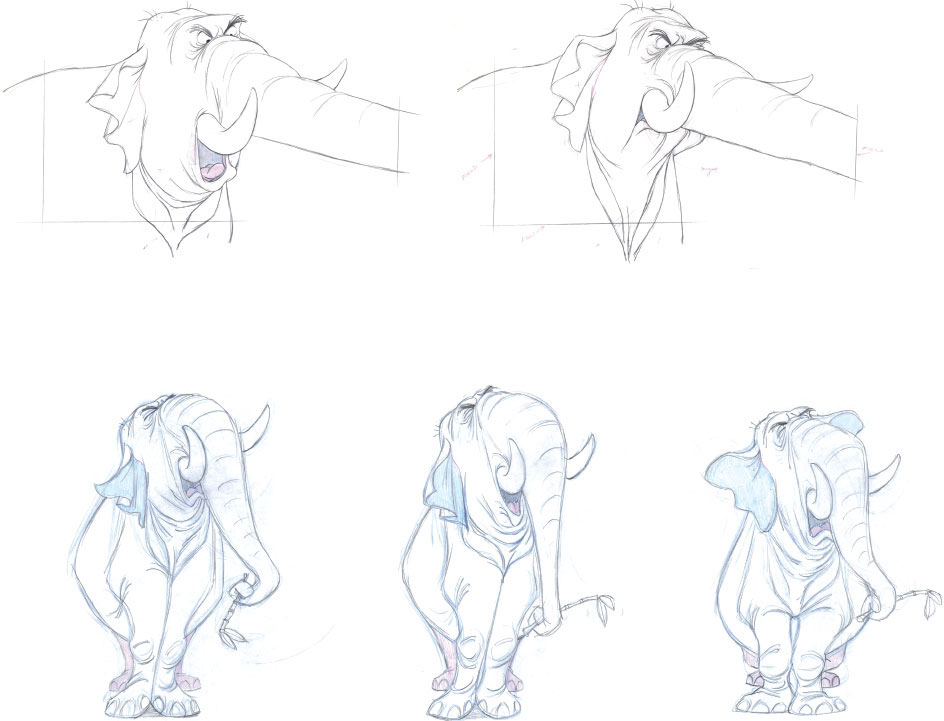

Following The Sword in the Stone was The Jungle Book, which turned out to be the last animated film Walt Disney supervised. By that time the group of directing animators had shrunk to only four: Milt Kahl, Ollie Johnston, Frank Thomas, and John Lounsbery. Other animators had either left the studio or they functioned in non-supervisory roles. Nevertheless the movie became one of the studio’s major hits, particularly in Europe. John got the assignment of animating Colonel Hathi and his herd of elephants. Every character in this film is beautifully developed as a character, and Hathi is no exception. He is a member of Her Majesty’s Fifth Pachyderm Brigade, and therefore demands respect and military readiness. Lounsbery was in his element bringing this oversized personality to life. Just the way he walks during the march as well as during inspection has so much character. He is an old-school military type, and even though he is past his prime, military drill still runs through his veins. John made great use of his loose skin around his neck during dialogue scenes. Even his tusks are involved when he talks, and are part of the overall facial squash and stretch. (In theory this goes against rules of anatomy, since an elephant’s tusks are connected firmly to his skull, not his flexible jaw.)

The retired Colonel still retains his military bearing.

© Disney

To the dismay of his herd, Hathi re-recites the story of when he received a special military award: “It was then I received the Victoria Cross for bravery above and beyond the call of duty. Ha, ha, discipline, discipline was the thing!” His slow walk toward camera during the line is one of the best animated personality locomotions ever. He looks extremely pleased with himself as he rotates a leg outward, before slamming it to the ground, parallel to the opposite leg.

John Lounsbery enjoyed bringing Colonel Hathi’s oversized personality to life.

© Disney

After The Jungle Book’s success, the studio continued producing lighthearted animated comedies with productions like The Aristocats and Robin Hood. Lounsbery was again assigned to animating characters that had been designed and developed by Milt Kahl. He drew scenes with the butler Edgar and the lawyer Georges Hautecourt for The Aristocats.

Georges Hautecourt and Edgar from The Aristocats.

© Disney

The Sheriff of Nottingham collects tax money from inside Otto’s cast.

© Disney

For Robin Hood, John animated scenes that involved the Sheriff of Nottingham and Otto, the hound dog.

The animation on those last assignments is very good, but somehow John felt he was working in the shadow of Milt Kahl, who was still given the opportunity to express his own style when it came to developing new Disney characters. (As Milt put it: “I WAS the Disney style!”)

Because John was so well-liked around the studio, and the fact that he enjoyed mentoring young artists led to the decision to make him a co-director on the next film, The Rescuers. Lounsbery missed the drawing board though, and had hopes to return to animating in the future. Unfortunately his untimely death prevented this from happening. Today many animation students gravitate toward studying Lounsbery’s vast body of work. His comedic acting and his fine drawing abilities combined with his bold use of squash and stretch are worthy of close investigation. John himself would be flattered by all of this attention. He stated modestly toward the end of his life: “I just worked hard and kept trying to become a good animator.”

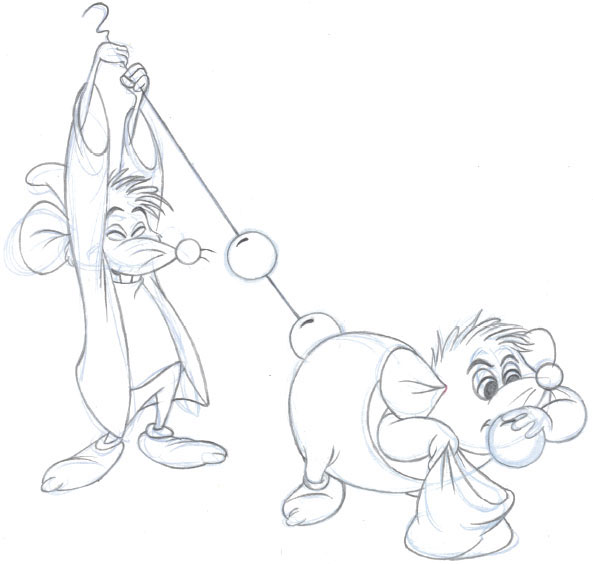

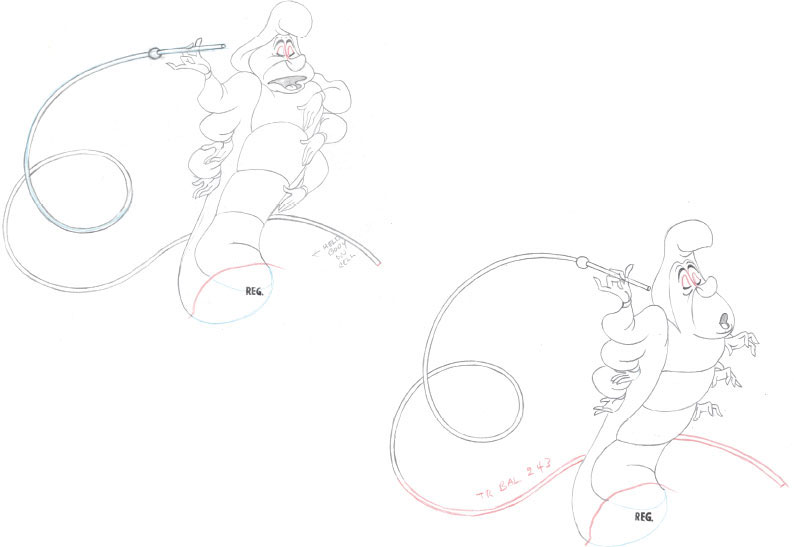

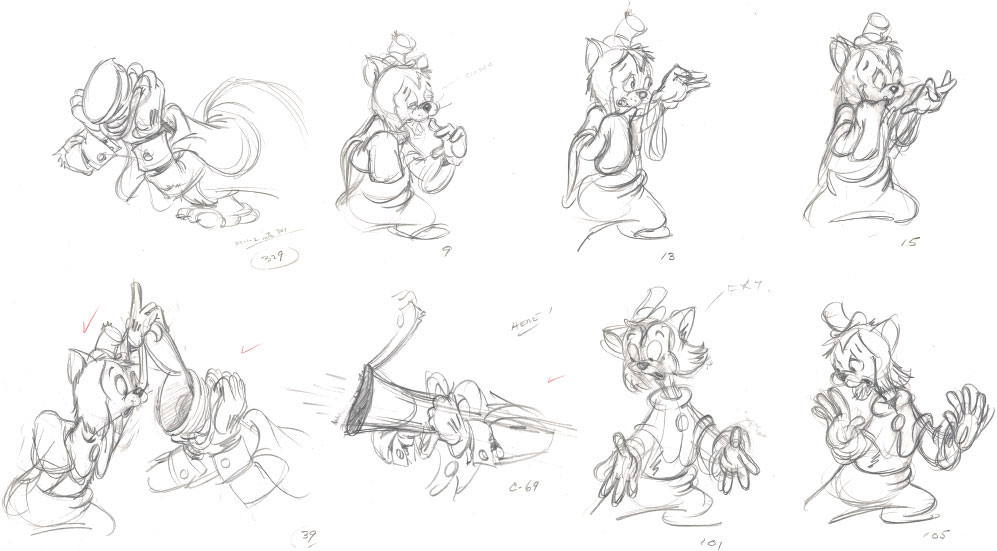

1940

HONEST JOHN AND GIDEON

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 3, Sc. 45.2

In most cases two characters who share a scene are drawn on different levels, unless they touch, in which case they are drawn on the same sheet.

Gideon is trying desperately to free Honest John from the awkward predicament he had put the fox in. The scene description in the animation draft reads like this:

EXT. CU – CAT biting fingernails – timidly reaches up – lifts lid of hat – Fox yells: “GET ME OUT OF HERE!” Cat scared, closes lid of hat – pats it – then gets brilliant idea.

This kind of a scene calls for broad staging of the poses as well as crisp timing.

Logic goes out the window when Honest John attempts to remove his hat. There is no way the whole fox head would fit into these squashed drawings, but it looks funny, and that’s the important thing.

© Disney

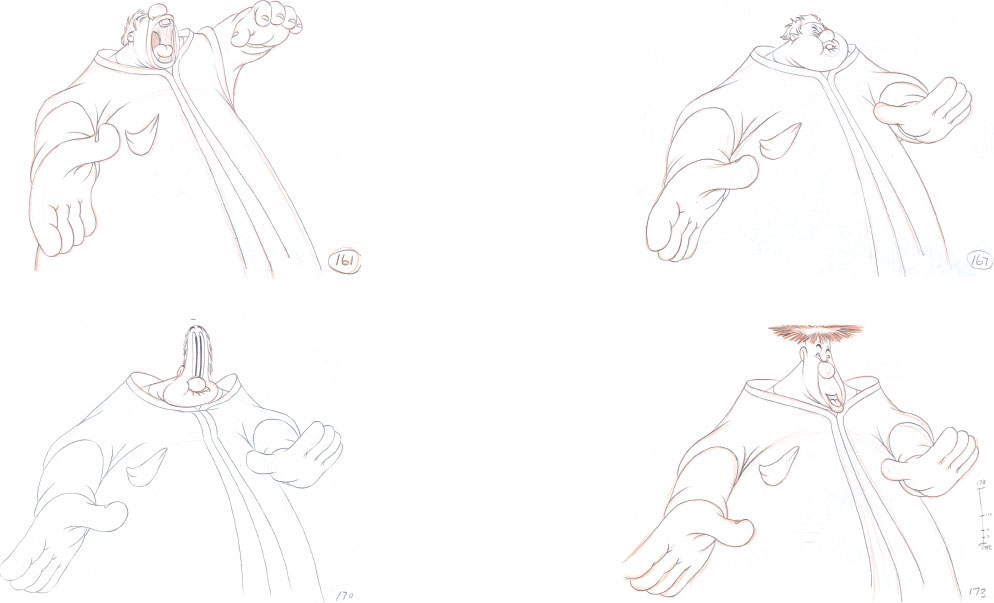

1955

JOE

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 7, Sc. 68

Tony, the proprietor of the Italian restaurant, argues with Joe, his chef, who questions his boss’ announcement that Tramp just ordered diner. “Tony, dogs don’ta talk!”

In this scene Tony responds vigorously: “He’sa talking to me!”

Energetic hand gestures emphasize his attitude, and his expressions are broad and extreme. The body is holding relatively still, so the motion of hands and face reads clearly. Lounsbery was an expert in drawing hands and had no problems depicting them from any angle, as is evident in these key drawings.

There are only two main poses in this scene. During the first one Tony’s hands gesture away from his body. The second pose shows him pressing his hands against his chest on the word “me.” The animation is energetic, but carefully controlled, so it doesn’t come off as looking too busy.

© Disney

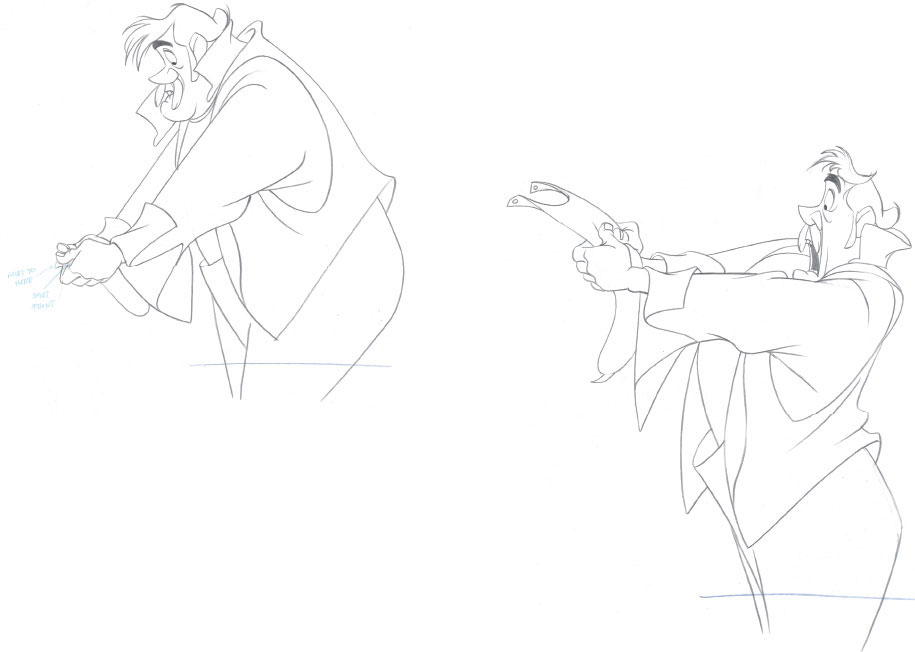

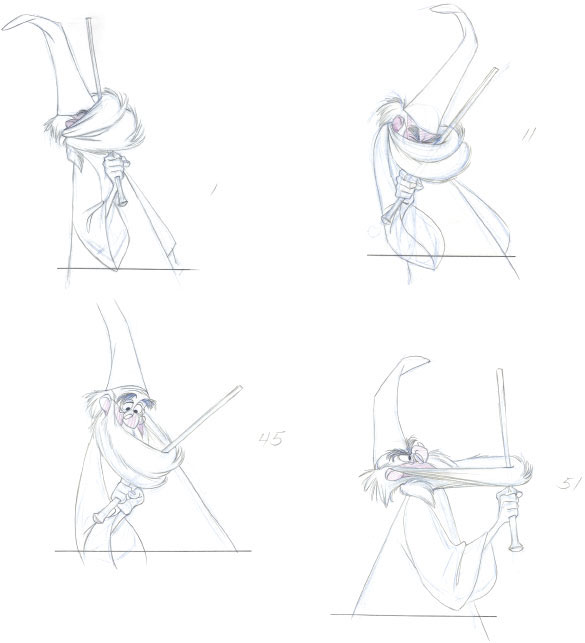

1959

KING HUBERT

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 13, Sc. 28

“Never underestimate the value of props in animation!” Milt Kahl once said.

John Lounsbery knew this very well, and when he animated this scene, a bottle came in handy to help King Hubert punch a line of dialogue.

Hubert and King Stefan argue over the possibility of their children not liking each other, before they are supposed to get married. Hubert angrily approaches Stefan: “Why doesn’t your daughter like my son?” Lounsbery wanted to emphasize the word “son,” and there are many ways he could have done this, like banging his fist on the table. But, since earlier on, the two kings were happily toasting and drinking wine, it seems a good choice to use a wine bottle.

Lounsbery feels comfortable portraying strong, exaggerated emotions, and every one of these drawings was done with ease and pleasure.

© Disney

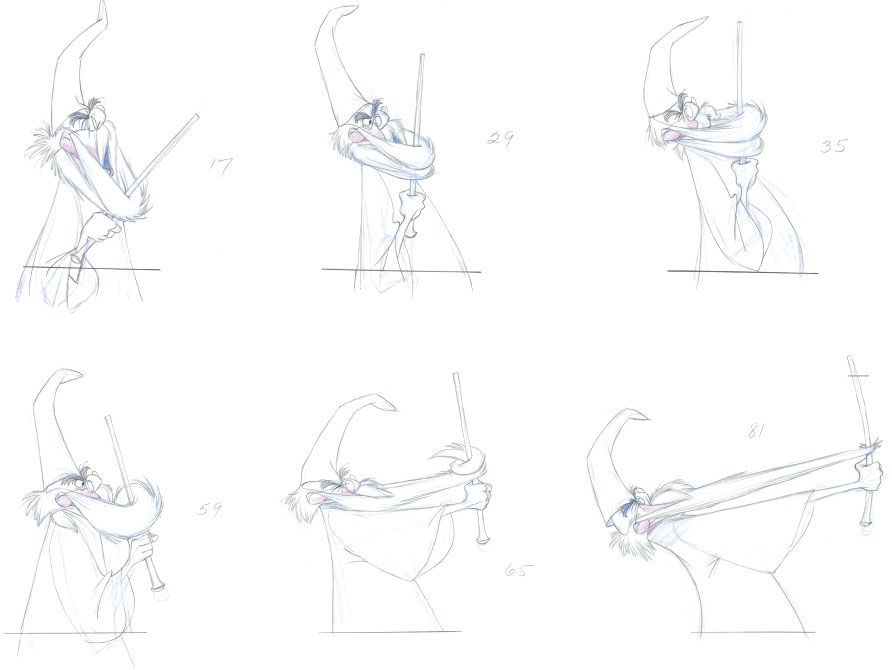

1963

MERLIN

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 2, Sc. 309

Merlin begins to educate Wart about the world as they both leave his house in the woods: “Everybody has problems; the world is full of problems.” The magician closes the door behind him, before realizing that his long beard has got stuck. In an effort to free himself, the beard snaps away from the door and ends up in a tight loop around Merlin’s neck. He uses his magic wand to uncurl the beard. After three efforts it finally comes loose, but forms a giant, fluffed hairball.

This close up scene shows Merlin’s attempts to straighten out his beard to its natural shape. He uses both arms repeatedly to bring it back to its original appearance.

This visual gag helps define Merlin’s befuddled charm. He is far from being the perfect, dignified sorcerer. It is interesting to note that the beard takes on a completely abstract shape after being pulled. This transformation comes unexpectedly, and gets a big laugh.

© Disney

© Disney

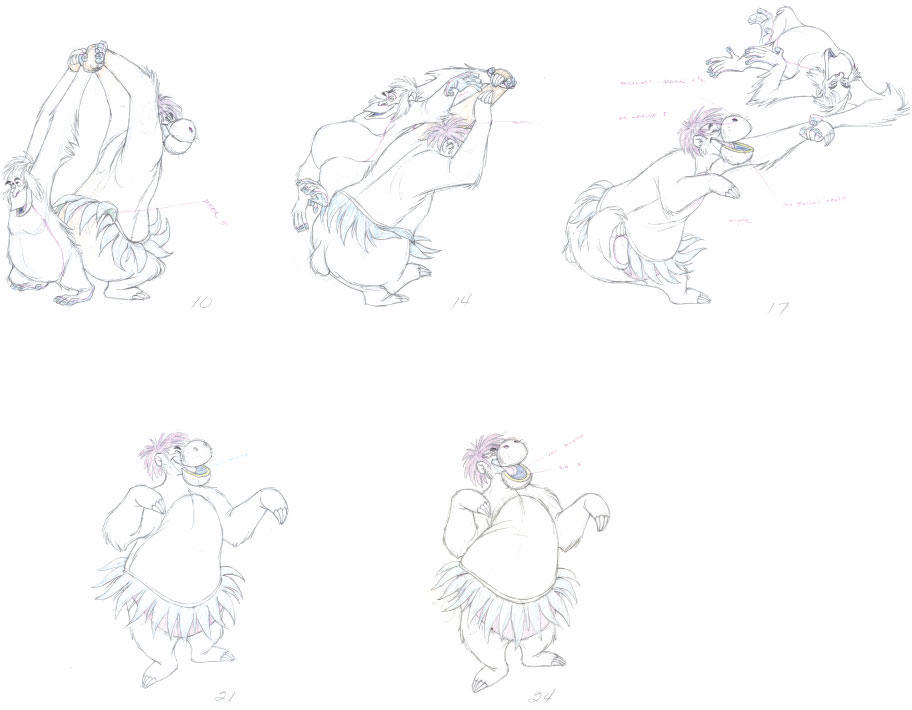

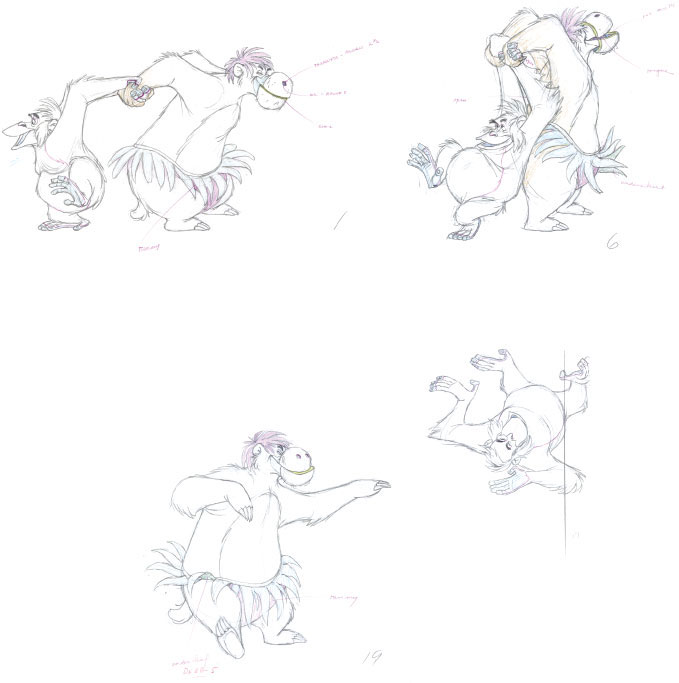

1967

BALOO AND KING LOUIE

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 7, Sc. 68

During the song “I Wanna Be Like You” Baloo, disguised as an ape, and King Louie end up sharing a few dance moves. As things escalate, Baloo grabs the orangutan from the back and catapults him forward. This is a short continuity scene, but Lounsbery’s animation shows careful choreography and drawing during this wild moment.

The reversal of Baloo’s spine, when he lifts and throws King Louie, helps to give this action the correct physicality. The scene works without any cartoony distortions, Lounsbery maintains proper anatomy for the two characters throughout. A simple but spirited piece of animation.

© Disney