After finishing work on the film One Hundred and One Dalmatians in 1960 Marc Davis was looking forward to developing the European tale Chanticleer as a possible follow-up animated feature. The story centered on a cocky rooster who believed that he himself was responsible for each sunrise because of his early morning crowing. Marc drew endless designs for this character and the rest of the cast. There were chickens, ducks, foxes, owls, and many other animal types. He also storyboarded several sequences for the project. When the time came to present this work-in-progress to Walt Disney and several businesspeople, Marc was anxious to share what he had been working on. After the designs and story work were pitched, an awkward silence dominated the room. Before Walt could make a comment, one executive bawled: “You can’t get a personality out of a chicken!” The group left the office without any further discussion.

Marc was crushed. He felt let down after just having pitched some of the best drawings he ever did at the studio. It tuned out that was the moment his career as an animator was over. Moving forward Marc needed a different kind of artistic challenge, and when Walt Disney offered Marc a top position in his Imagineering department, Marc accepted. This new job still offered the challenge to bring things to life, but not through drawings on film. Instead Walt needed Marc to develop and design electronic mechanisms that would animate robotic figures such as Mr. Lincoln, children from around the world, and a great number of pirates. Disney animation lost one of its all-time greats, but Disneyland benefited greatly from Marc’s artistic influence on some of the most iconic theme park rides. His 25 years as an animator and story-man provided the perfect experience for telling stories within a real environment inhabited by all sorts of Audio-Animatronics characters.

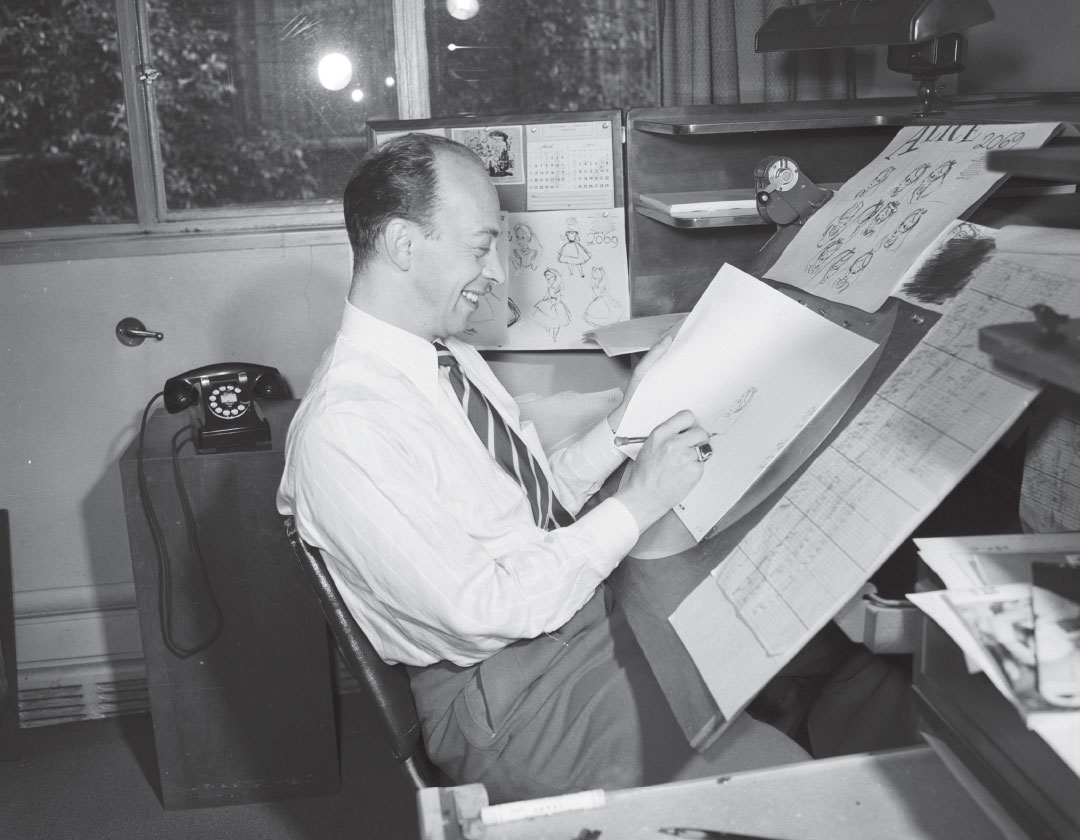

Back in 1935, young Marc Davis was looking for a job as a newspaper cartoonist, but this was the time of the Great Depression and steady employment was hard to find. One day he found out that Walt Disney was looking for artists to help him expand the art of animation. He applied and was hired on the spot. His portfolio was full of thorough human and animal anatomical studies.

They showed a standard and level of draftsmanship never before seen in an applicant’s submission. Marc had spent years drawing animals at the San Francisco Zoo, where he observed their skeletal structure but also their individual ways of moving. With no prior animation background, he received training to become an assistant animator. When the studio began animation for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Marc was asked by senior animator Grim Natwick to assist him on the character of Snow White herself. Natwick’s drawing style was loose and sketchy, but he knew that a fine draftsman like Davis would be a great asset to him for maintaining the realistic look of the princess. Marc at first was a little surprised to be asked to draw the girl; after all, he had been known around the studio for being an expert in depicting animals. But the way he sketched the female form in life drawing classes was equally impressive. As a matter of fact, this early assignment would be the start of his career as an animator of leading ladies, both good and evil.

Natwick was grateful for Marc’s fine work on the title character, and he offered him the chance to animate a couple of scenes during the dance sequence with the dwarfs. Marc knew that drawing Snow White’s head looking good at any angle would not be an easy task to accomplish. So he produced a small sculpture of her head that would help him define correct facial perspectives. Looking at his first animation, it is astonishing to see how elegantly Snow White moves as she dances in the dwarfs’ cottage. The main motion was based on live-action reference, but the overlapping action of her hair and dress needed to be enhanced and broadened in order to look natural in animation.

Snow White dances in the dwarfs’ cottage.

© Disney

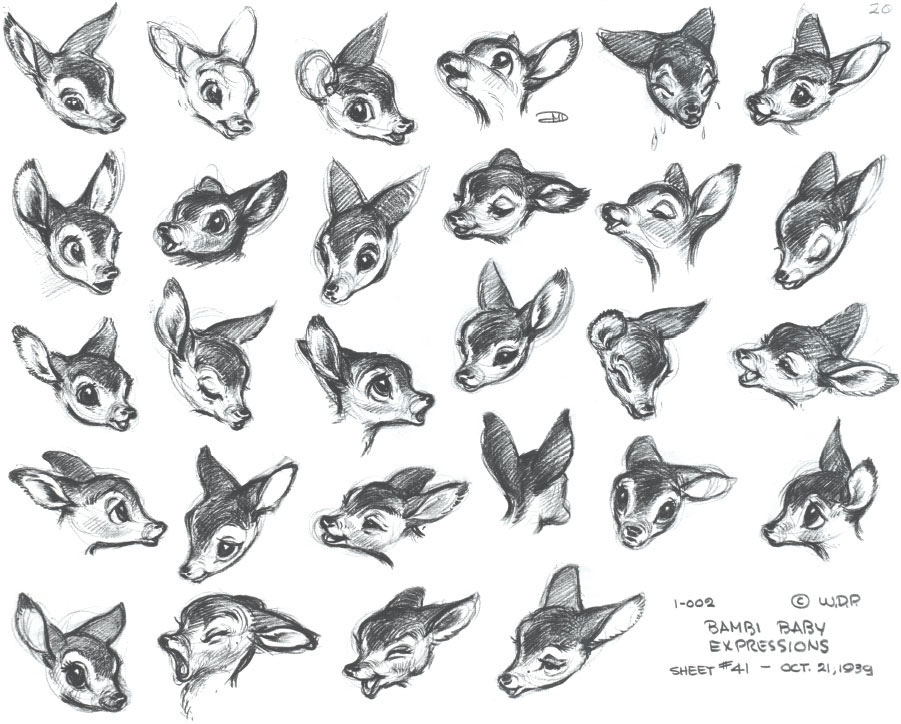

She certainly wasn’t an easy character to get started on as an animator and learn the tricks of the trade, because everything about Snow White is subtle. Usually newcomers to the animated medium receive assignments with broad characters like Goofy or Donald Duck, who require a much more extensive use of squash and stretch in the animation. Marc wouldn’t get the chance to work on such types until years later. His last assistant work was for the 1938 short film Ferdinand the Bull, before Walt Disney asked Marc to join the story unit for Bambi, a film he would work on for the next six years. Everyone at the studio knew about Marc’s expertise in animal drawing, and since the film’s characters were to be drawn with more realism than ever before, only top draftsmen were assigned to the movie. At the beginning, Marc needed to figure out an appropriate design style for Bambi, Thumper, Flower, and the rest of the cast.

These personalities were supposed to express human emotions while retaining their specific animal behavior. If drawn too realistically, they would not be much fun to animate. If drawn in a very caricatured way, they would not match the serious tone of the story material.

Luckily even as a young artist Marc had good judgment and his early drawings show just the right combination of real animal anatomy and animatable forms. In order to give young Bambi childlike expressions, Marc studied photographs from a book about juvenile behavior. The results impressed Walt Disney and animator Frank Thomas, who later stated: “Without all of Marc’s design research, we couldn’t have made the movie.”

FACING PAGE These head studies show that Bambi was able to go through a wide range of human emotions.

© Disney

Marc spent four years developing story sequences that would inspire background artists and animators to bring the world of Bambi to life. The extraordinary draftsmanship in these sketches proved that there was great potential in translating Felix Salten’s book into an animated feature film. The poses are solid, and their staging makes the characters relate strongly.

These sketches show Davis’ extraordinary draftsmanship.

© Disney

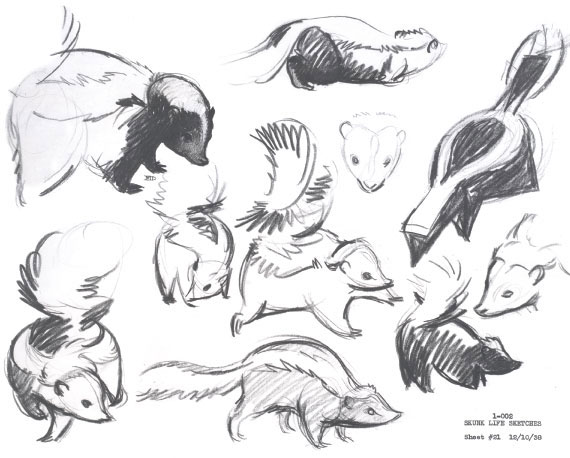

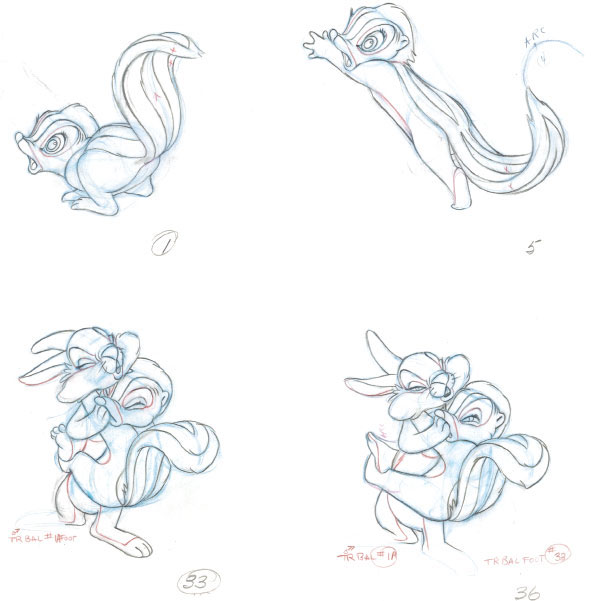

Toward the end of story development on Bambi, Walt Disney told Marc that he would like to see his drawings on the screen, but animated. “So he sent me to see Frank Thomas and Milt Kahl. Walt asked them to make an animator out of me,” Marc recounted later. A short training period followed, during which Marc studied the work methods and philosophies of these two established animators. Milt Kahl brought superior drawing and grand design to his scenes, while Frank Thomas always started out by analyzing the character’s emotions. Eventually Marc was assigned to the character of Flower, a kind and melancholic skunk. A de-scented live animal was brought to the studio, providing Marc with the opportunity to study his subject up close. Before animating his first scene, he created many rough model studies of real skunks in order to achieve the realism needed for the final version.

Early studies show Marc’s attempts to capture the essence of a skunk. Black and white fur markings already create interesting design patterns.

© Disney

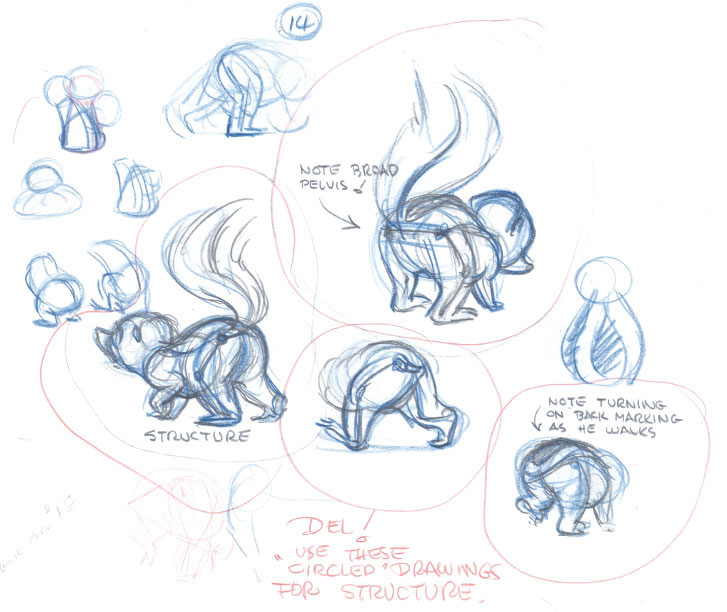

Further explorations lead to the final character design, but even at this stage it was important to Marc to develop a full understanding of the inner structure of this cartoon animal.

Once the inner workings of the skunk’s body are explored, the animation will appear believable and plausible.

© Disney

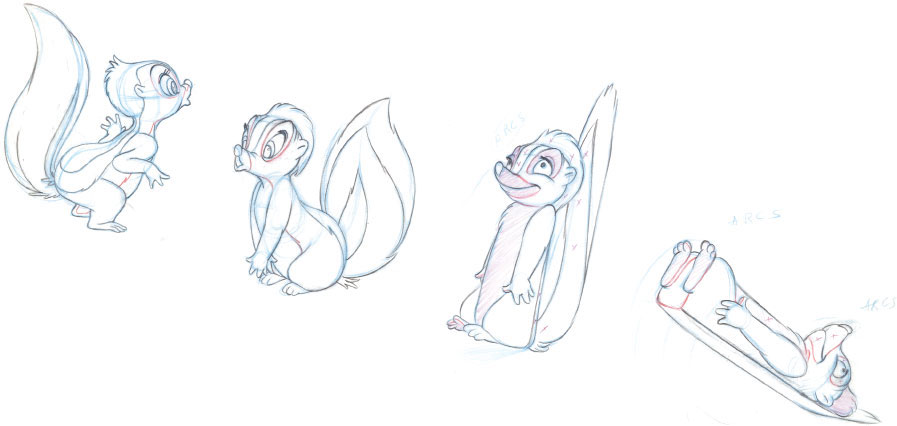

Marc ended up drawing most of Flower’s scenes as well as the ones that involved a girl skunk. When these two characters meet, they are instantly twitterpated, and the situation turns into the most surreal and cartoony sequence of the whole film. After a few flirtatious gestures their mouths “accidentally” make contact, resulting in a surprise kiss. Flower actually blushes, he turns bright pink, and his body takes on the shape of a square brick. He then falls backward and bounces on the ground like a stiff piece of wood. It is a very unusual gag within this realistic film. Audiences were used to watching Donald or Goofy going through routines like this one, but to see Flower’s reaction of his first kiss being portrayed in such a broad manner must have seemed somewhat unexpected. The reason the scene works and always gets a big laugh is because Marc had previously established Flower as a completely convincing character in the way he moved and expressed himself. His soft-spoken voice suggested slow and subtle movements. But here, by contrast, his feelings of first love turn into an over-the-top animated moment. Through it, the skunk becomes even more likeable because he shows that even he is capable of an extreme emotion such as love and passion.

Flower’s over-the-top reaction to his first kiss was unusual in the otherwise realistic film, but Marc Davis made it work.

© Disney

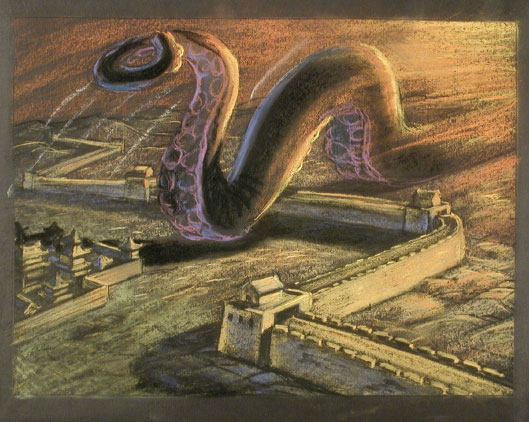

Intense emotions were again called for when Marc Davis briefly returned to story work for the wartime propaganda documentary Victory Through Air Power. The film was based on the book by Major Alexander de Seversky. Marc developed the final climactic battle between the American Eagle and the Japanese Octopus. This is a short sequence, but highly dramatic staging and editing combined with a stylized color palette created dramatic moments.

It is interesting to point out that Marc’s story sketches made it virtually unchanged to the screen.

All the power and drama evident in his drawings was captured by the sequence’s art direction and Bill Tytla’s powerful animation.

These story sketches show Davis’ ability to visualize a fierce action sequence.

© Disney

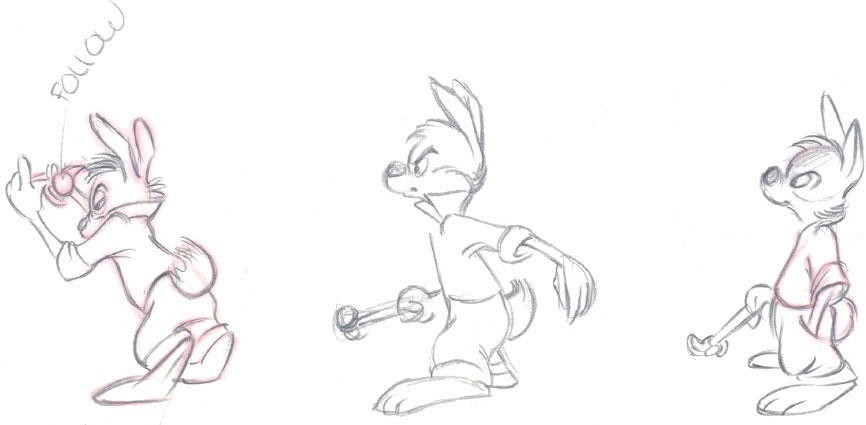

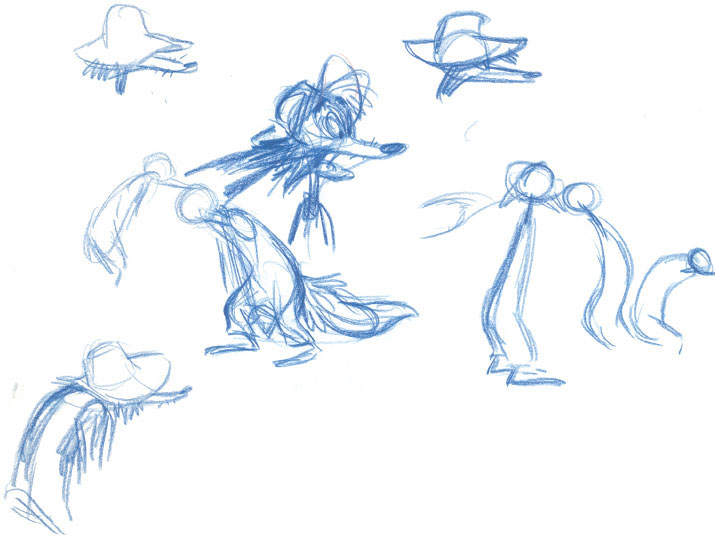

By the early 1940s, Walt Disney was aware of Marc’s multiple talents as an animator, story-man, and designer. The film Song of the South was in early development, and Marc was the first animator to be assigned to the project. He started out by exploring a style for the animal characters. Even in these initial sketches, Marc is already looking for ways to enhance the personalities graphically. While these character types walk on two legs, they retain their distinctive animal attributes: the cunning fox and the slow but strong bear.

The personalities of Brer Fox and Brer Bear (opposite) come across even in these early sketches.

© Disney

In this film, Marc animated the introductory scene with Brer Rabbit when he is telling Uncle Remus that he decided to run away from his home in the Briar Patch. In the process of nailing his front door shut with a hammer, he hits one of his fingers. Things get worse when he angrily hits the hammer with one leg, which causes great pain and leads him to take a few jumps as he holds on to his foot. All the way through the scene he is carrying on a conversation with Uncle Remus about all the trouble he is getting into. It’s a terrific piece of acting business and reveals Brer Rabbit as a somewhat nervous and energetic, yet likeable character.

Right from the first scene Marc lets the audience know what kind of character Brer Rabbit is.

© Disney

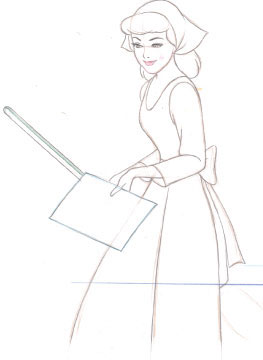

FACING PAGE Early color sketches already reveal Cinderella as a fun-loving person, who finds herself caught in a bad predicament.

© Disney

After completing animation on several key scenes with each of the three main characters Marc went on to work on movies like Fun and Fancy Free and The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, but not in an animation supervisory role. It just so happened that by the time he was assigned to any of these films, the top spots had already been filled by other animators. Frustrating as this might have been, Marc still produced solid character animation for the Bongo section as well as the Mr. Toad sequence. When Cinderella went into production, Marc did again join the group of directing animators. He helped design the title character’s appearance as well as some of her outfits.

Cinderella’s charming but mild-mannered demeanor presented a challenge for Marc Davis and Eric Larson, who supervised her animation. A character who doesn’t show strong emotions is very difficult to bring to life. Without any eccentricities to play with, your range as an animator is somewhat limited. Only subtle and realistic motion is called for. And yet there are moments in the film when Cinderella projects feelings such as anger and even cynicism.

When the stepmother is holding a music lesson for her two rather untalented daughters, Cinderella is cleaning the floor downstairs while singing her song “Sing Sweet Nightingale.” All of a sudden she realizes that Lucifer, the cat, has left dirty footprints all over the floor. Cinderella angrily tosses the washing cloth and goes after the evil cat, when suddenly there is a knock at the front door. She opens it and receives a letter from the palace. The mice witnessing the situation are as surprised as she is. Cinderella wonders about the letter’s content, then turns to the mice and says: “Maybe I should interrupt the ‘music lesson?’” Her brief, wide-eyed expression clearly communicates what she really thinks about the singing coming from upstairs. This scene along with many others was acted out by actress Helene Stanley. Her filmed performances served as a basis for the animators’ work. Marc knew exactly how to work with such reference; he chose carefully which parts of the live-action were important to his animated performance and which parts proved extraneous.

Cinderella and the letter from the palace.

© Disney

Marc also animated the iconic moment when Cinderella’s ragged outfit—with the help of the Fairy Godmother—is transformed into a beautiful gown. It is common knowledge that this scene became a favorite of Walt Disney. Marc stated later rather modestly: “It’s not because of my animation. This scene represents Walt’s philosophy that good things can happen, that your dreams can come true.”

It is interesting to see that the final clean-up drawings were made right over Marc’s rough animation drawings. This process saved time, but was only possible whenever the animator drew the character completely on model.

© Disney

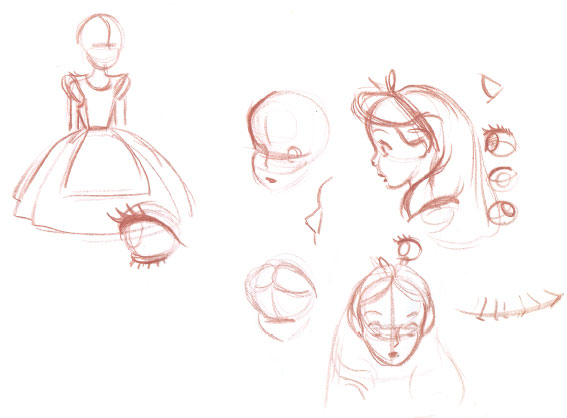

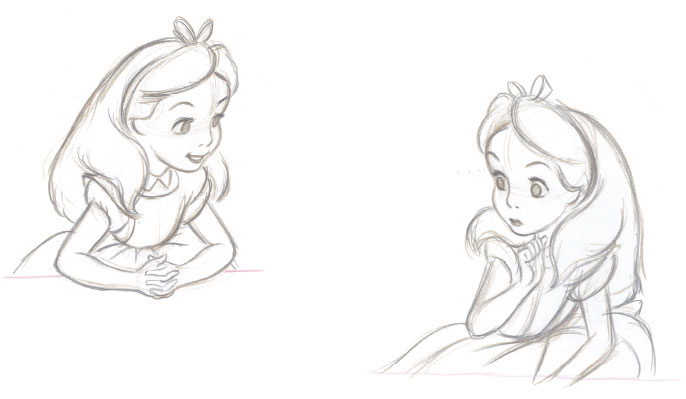

The animation of Cinderella required top-notch draftsmanship, and Walt knew that the heroine for his next feature Alice in Wonderland also needed to be assigned to animators who were competent in animating a female lead. It is obvious why Marc ended up in the unit that was responsible for bringing Alice to life. He did not necessary welcome the assignment, because he knew that the film’s entertainment would come from all of its eccentric characters, such as the Mad Hatter or the Queen of Hearts. While personalities like Cinderella or Alice don’t make audiences laugh out loud, they are essential to the story and must be handled in a believable way—they need to come across as real. When watching Alice in Wonderland, the audience takes on the role of Alice, who reacts constantly to the nonsensical characters and situations she finds herself in.

Marc animated her in the Mad Tea Party sequence as she tries to solve silly riddles and plays along during a manic unbirthday party. Based on live-action reference Marc produced the most appealing and delicate drawings of Alice. Each of his rough animation drawings is so carefully executed that they hold up as individual illustrations. They are a joy to look at for more than a twenty-fourth of a second.

Marc’s rough drawings are delicate and appealing.

© Disney

The animator explores the dimensional forms of Alice’s face in detail.

© Disney

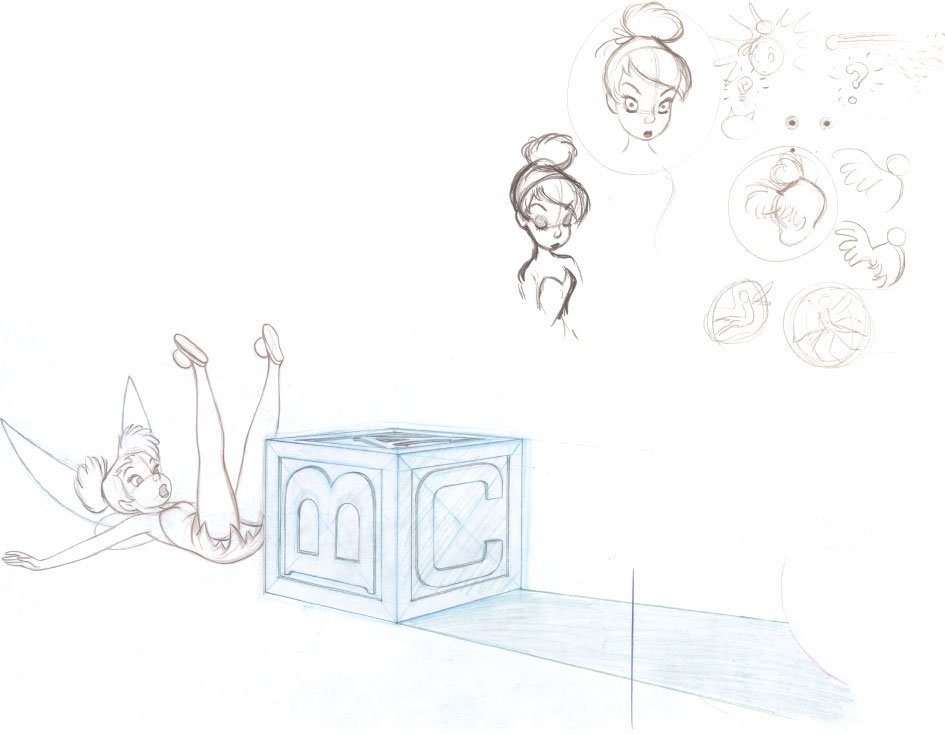

Marc’s next assignment would be a female character again, but this time her personality was capable of a wider range of emotions. Tinker Bell from the film Peter Pan did not talk, which presented an interesting challenge to the animator. Her whole body language needed to communicate her inner feelings, which were mostly driven by her jealousy toward Wendy. And even though Tinker Bell at one point puts Wendy’s life in danger, Marc manages to present her as an utterly likable character. We see her first in the Darling children’s bedroom as she lands on a mirror to inspect her reflection. Her mood changes from delight to shock when Tink notices the size of her hips. This reaction makes her instantly relatable and sympathetic.

Designed with ultimate appeal and feminine elegance, Tinker Bell admires her mirror image.

© Disney

Marc’s animation sketches were turned into clean-up drawings by Clair Weeks.

© Disney

When Peter Pan’s first attempts to teach the children how to fly fail, Tinker Bell is delighted. Wendy, John, and Michael fall from the room’s ceiling and crash on to a bed. Tink observes the situation sitting on an alphabet cube. She laughs mischievously, which causes the cube to turn over, resulting in her own crash—a lesson about the fact that taking pleasure in the misfortunes of others will often have consequences! Clean-up artist Clair Weeks turned Marc’s animation sketches for this scene into delicate clean-up drawings while maintaining a very high level of draftsmanship.

One of Marc’s “doodle” sheets shows his research for Tinker Bell’s facial features and hair movement. By placing her mouth low and practically eliminating the jaw, she appears more pixie-like and less realistic.

© Disney

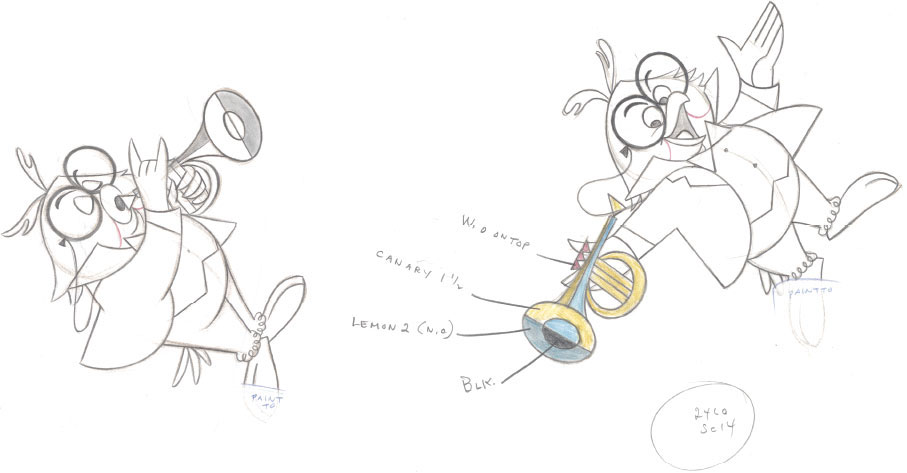

While Tinker Bell was designed as a three-dimensional figure, along with the rest of the cast of Peter Pan, graphic changes were starting to surface at The Walt Disney Studio during the 1950s.

Marc Davis was one of a few artists who influenced this development, while other animators initially resented the modern two-dimensional approach to drawing. Pablo Picasso had become the world’s most celebrated artist, and Marc—together with Milt Kahl and Ward Kimball—welcomed a change in character styling influenced by modern art. In 1953, Kimball directed the short film Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom, which turned out to be a clever history lesson about musical instruments. Its character designs resemble flat paper cut-outs, imagery found in mid-century cubist art. Marc Davis was one of the key animators who worked on the short, and he welcomed the challenge of animating within this new graphic, sophisticated style. The characters of course still needed to act and entertain, but the way they were drawn indicated that a new era had begun at Walt’s studio. For this groundbreaking film, Marc focused on developing the outgoing personality of the narrator, Professor Owl.

Strong curved and straight lines define the appearance of the film’s characters.

© Disney

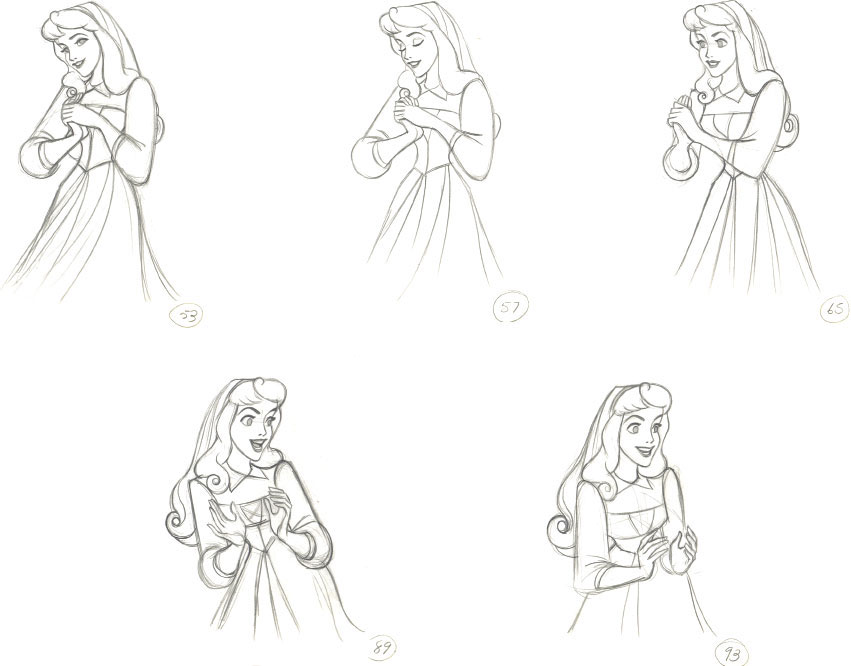

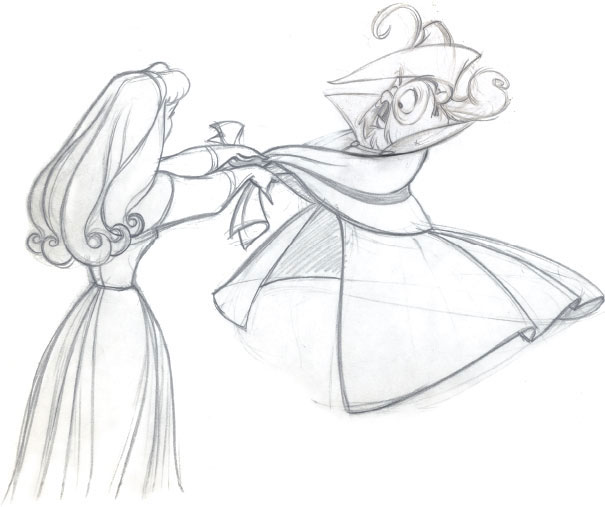

This change in approach to drawing continued on and was further developed for Disney’s elaborate feature Sleeping Beauty. Marc skipped the production of Lady and the Tramp, allowing him to design, animate, and establish Sleeping Beauty’s two main characters, Aurora and Maleficent. During a lecture Marc explained: “We did a lot more design with the characters than we had ever done before or would ever do again. Sleeping Beauty was more designed in two-dimensional shapes than any other character we’ve done.”

This initial design represents a young, princess, who does look 16 years old.

© Disney

In the final version, Aurora’s age could be 25. It is unclear why this aging process took place, perhaps a juvenile-looking girl didn’t fit the film’s sophisticated story.

© Disney

In this elegant key drawing, Aurora dances with a prince made up of various animals, including an owl and a squirrel. What a beautiful composition, even for a back view!

© Disney

Because of the degree of realism in the character’s design, actress Helene Stanley was again called upon to act out most scenes for Marc Davis as reference for his animation. He later explained to students about his use of live action. Marc compared this footage to a first rough pass of a scene: “You don’t start from scratch with a blank piece of paper, you already have something to look at.” The idea is to take what an actor has done and translate it into graphic, moving statements. Simply tracing the photostats would result in “floaty” animation without enough contrast in the timing. While some parts of a scene need to be sped up, others might have to be slowed down in order to feel right for graphic motion. Then there are special design patterns in Aurora’s hair and the fabric of her skirt. These things need to be invented and controlled by the animator. When the overall live acting is not satisfactory, the scene has to be reimagined by way of conventional animation. It’s fair to say that using live-action reference successfully is not as easy as it might seem. Marc animated Aurora’s most important acting scenes, including her encounter with the sympathetic forest animals, who desperately want the girl to find her prince.

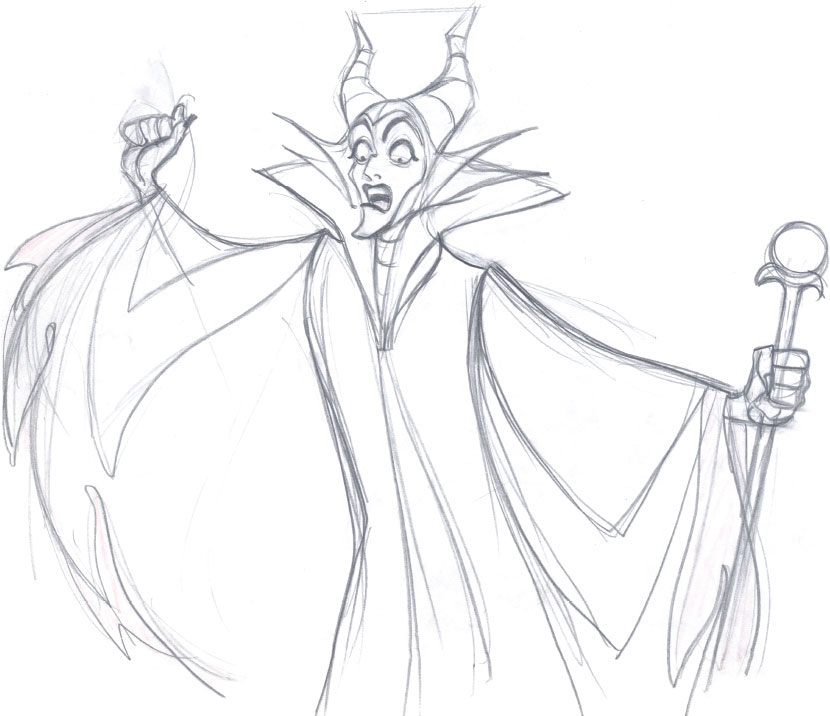

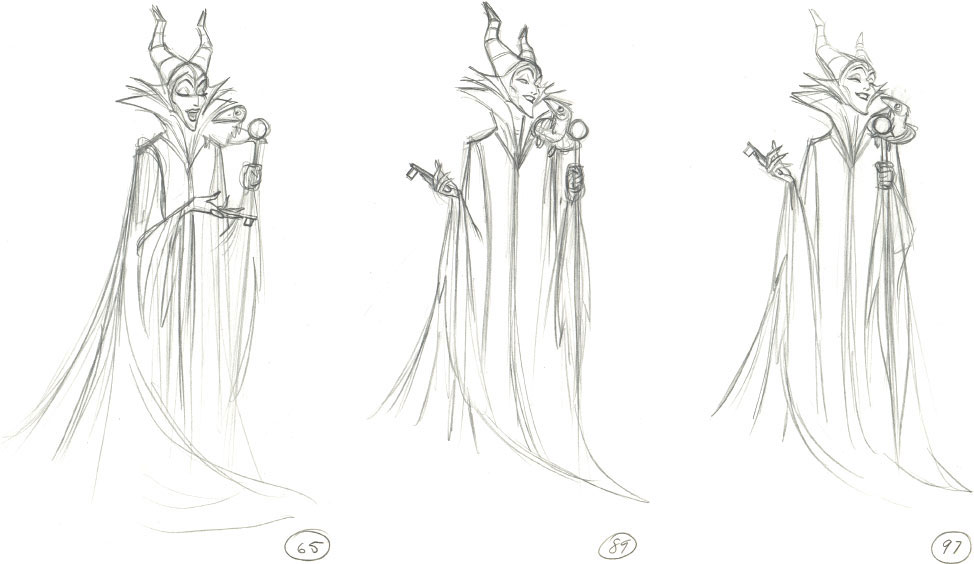

The film’s villainess offered even greater and more dramatic design possibilities. Maleficent needed to look visually stunning as well as intimidating. Her personality and voice were dominant and authoritative, and Marc new how to match those qualities with pencil and paper.

An early version of Maleficent’s design.

© Disney

In the end, added horns gave her appearance a devilish quality, and sleeves shaped like flames were used to great dramatic effect.

© Disney

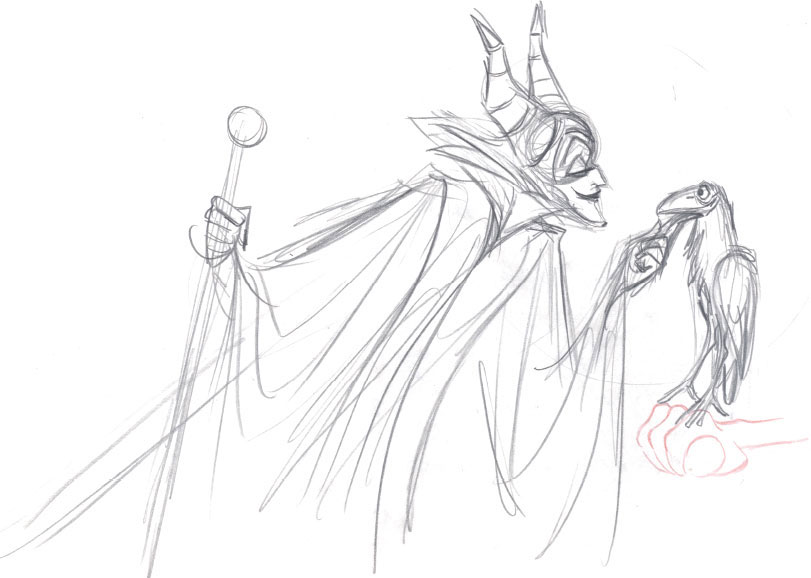

Marc took great pleasure in drawing this theatrical-looking character, but bringing her to life through animation was a different matter. As he stated, Maleficent for most of the time stood around giving speeches. She never came in physical contact with any of the other characters. This presented limitations in what you can do with her. Subdued acting and slow carefully conceived movements helped to make her believable to an audience.

The raven added a nice visual touch, and he also gave Maleficent the opportunity for some acting business. She could stroke his feathers or put him on her shoulder. The raven was also important as a story device when he is being sent away to look far and wide for the whereabouts of the princess.

A couple of dynamic, rough sketches demonstrate the way Marc lays out key moments of a scene, before animating it.

© Disney

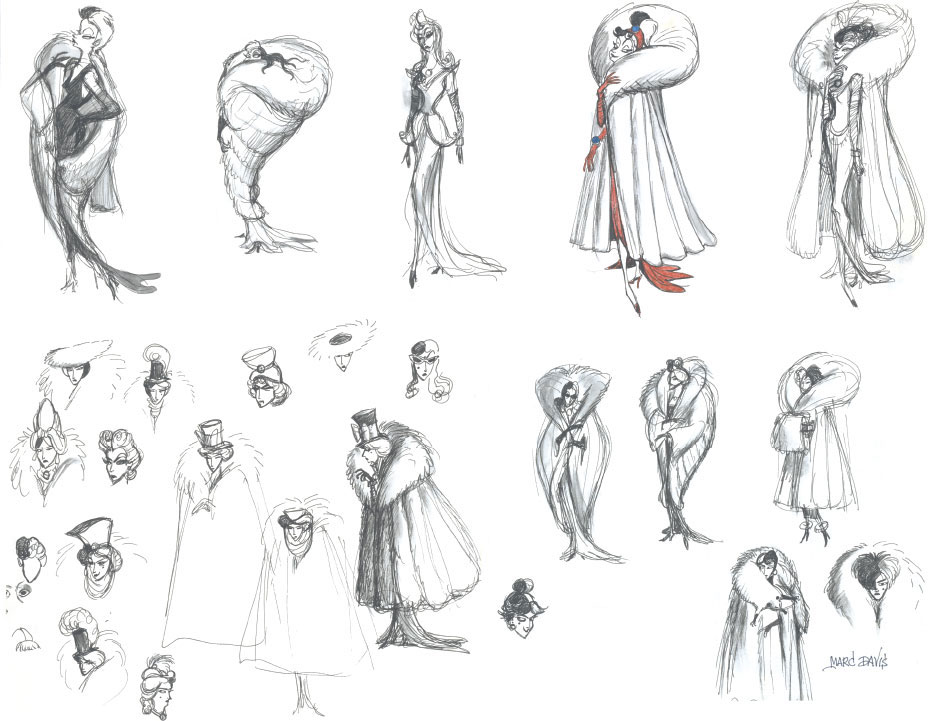

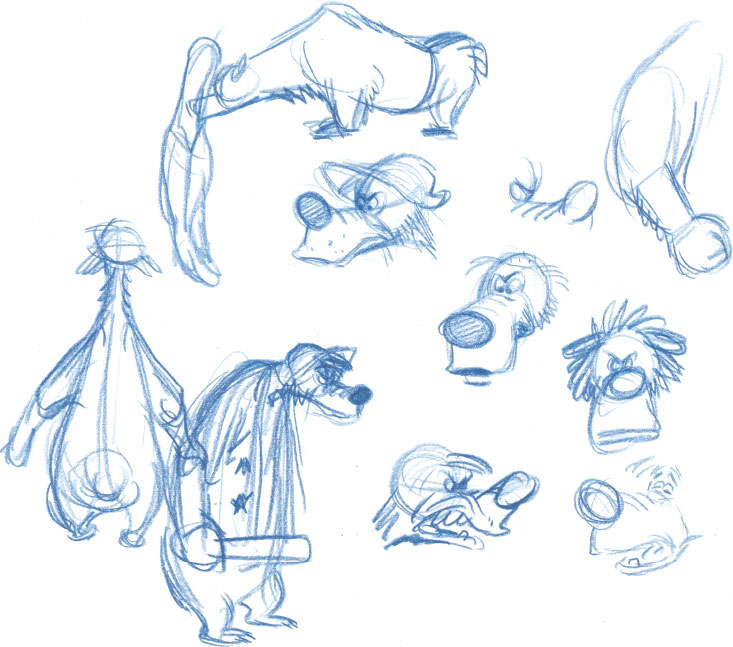

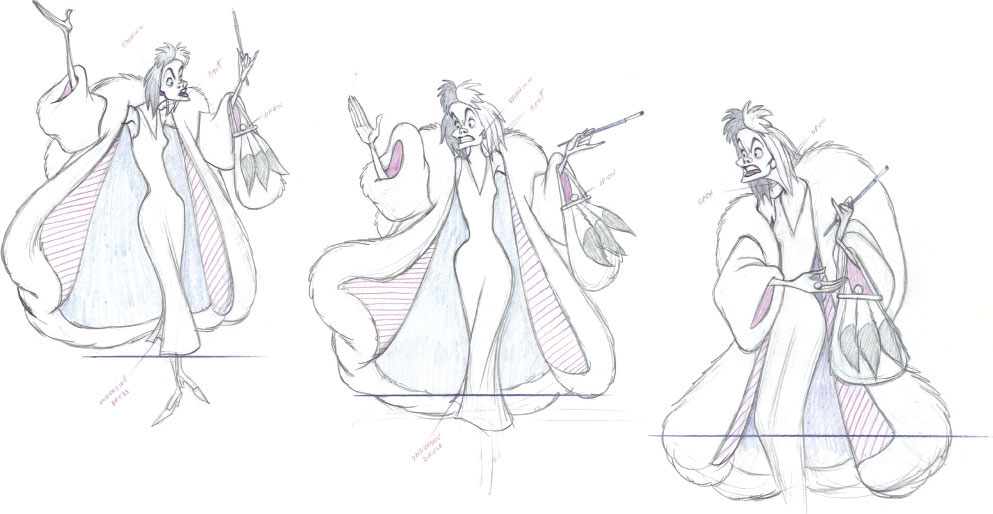

After spending close to five years working on Sleeping Beauty, where each drawing reached a level of perfection never attempted before, Marc received what would become the ultimate assignment of his animation career. Cruella De Vil in One Hundred and One Dalmatians encompasses all the qualities we have come to love in a Disney villain. Her over-the-top design is a graphic masterpiece, her ambitions are truly evil, and her bombastic screen presence makes her a favorite among animation fans. Unlike Maleficent, Cruella is very physical in her actions. She slaps her henchmen Jasper and Horace, she threatens Anita and Roger by getting up close to them, and she drives her car into a snowdrift while pursuing the dogs. Her drawing is full of contrast: a tall skinny body with extremely thin arms and legs, covered by an enormous fur coat. With that kind of dramatic portrayal, it is no surprise that she steals every scene she is in.

What is surprising is the fact that Marc Davis animated every single scene with this character.

Yet Cruella is not a simple design to draw. There are multiple sections of her fur coat, and just her handbag alone is very detailed. Marc animated her often on ones, which requires 24 drawings per second (animation on twos uses only 12). All this meant extra work, more working hours, and endless dedication. Cruella went through many design explorations before Marc found his villainess. All sorts of hairstyles, fur coat designs, and different facial features were considered at one time or another.

Actress Mary Wickes was filmed as she acted out many of Cruella’s scenes, but Marc’s animation goes so much further than Wickes’ performances. He exaggerated each gesture to maximize her flamboyancy. The fur coat’s motion re-enforces Cruella’s broad action, as it swings back and forth before coming to a stop. In order to make the coat feel heavy, it needed to be timed carefully. Anything heavy takes longer to change direction than something light, like a thin skirt.

For most scenes, Marc did every other drawing, with one even in-between left for the assistant to do. Most other animators would often call for two or three in-betweens to be done.

FACING PAGE Early ideas for Cruella De Vil’s design.

© Disney

But Marc’s philosophy was that the more drawings he did for a given scene, the more he controlled the action. Cruella De Vil became one of the most entertaining screen creations ever.

As an audience we can’t take our eyes off her because everything she does is shocking, surprising, or hilarious. If an animator ever left the medium on a high note it is Marc Davis with his unforgettable creation of Cruella De Vil.

We can’t help but wonder what artistic influence Marc might have had on future films like The Jungle Book or Robin Hood, but we will never know. Walt Disney needed him in other areas of his organization. Marc’s unique body of animated work set such a high standard that studying it can be somewhat intimidating. His characters are masterfully drawn and they show a huge range in their performances. Marc was able to capture the innocence of Flower, the skunk, as well as dramatic, theatrical qualities for characters like Maleficent and Cruella. But he would not want his work to intimidate; instead he would want it to inspire future generations of animators.

Cruella De Vil is one of the most entertaining screen creations ever.

© Disney

1942

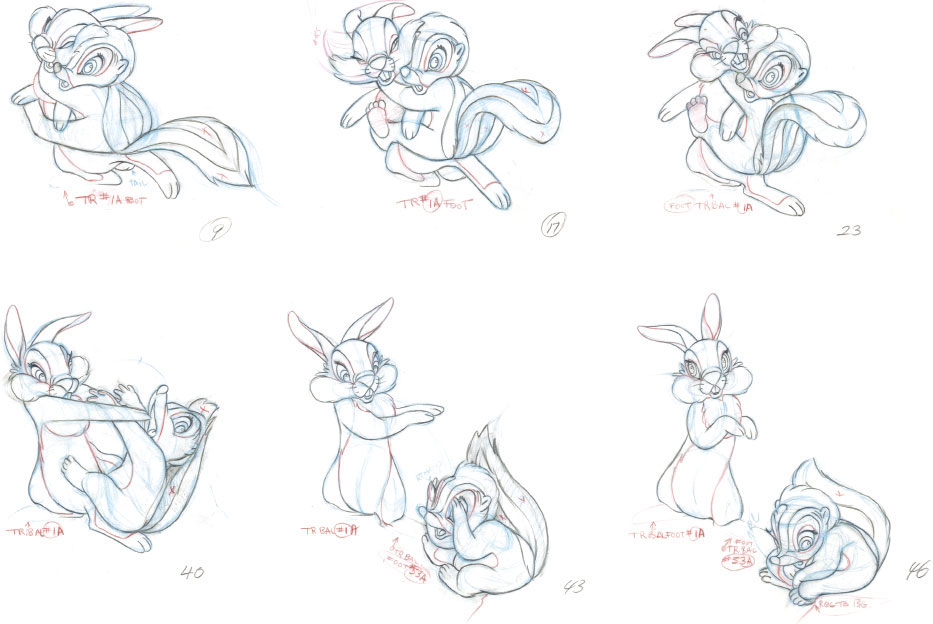

FLOWER AND THUMPER

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 10.1, Sc. 41

When adult Bambi, Flower, and Thumper run into friend Owl, they are being warned of becoming “twitterpated”: “…you run smack into a pretty face. Woo-woo!”

In this scene Marc animated Flower being spooked, as he jumps into the arms of Thumper, looking for protection. Thumper is not pleased and pushes the skunk off.

This is a cartoony moment, but the animation comes off as very believable, because both characters move with weight. As soon as Flower makes contact with Thumper, both characters swing to one side, before they settle back into a pose. The audience will believe in impossible situations as long as the animation shows real weight.

© Disney

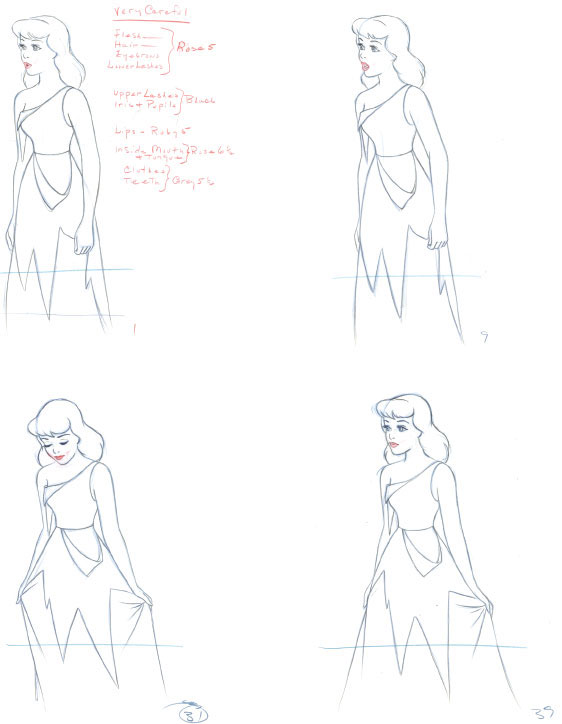

1950

CINDERELLA

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 3, Sc. 10

The Fairy Godmother tells Cinderella: “You can’t go to the ball looking like that.”

Her melancholic reaction is subtle and underplayed: “The ball? But I’m not…”

Marc knew that simplicity is best when showing a character feeling dejected.

Cinderella lowers her head as she glances at her torn dress. Her hands hold it up slightly as a sort of reality check. The ball is out of reach now.

When a realistic character like Cinderella moves in such an understated way, the quality of the drawing becomes paramount. In particular, her face needs to be drawn with perfection from any angle. Cinderella’s expression is a mixture of resignation, but also dignity. The audience feels a certain pathos and clearly roots for the girl.

© Disney

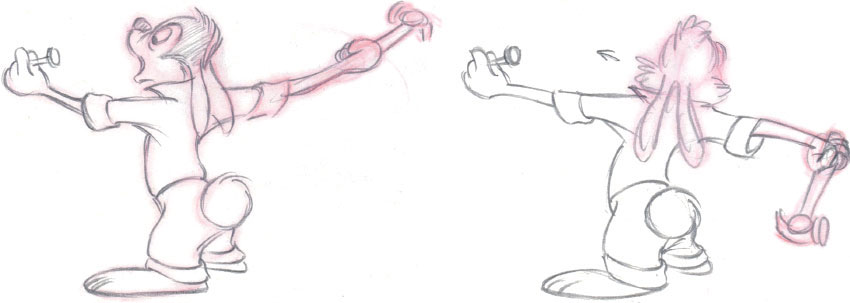

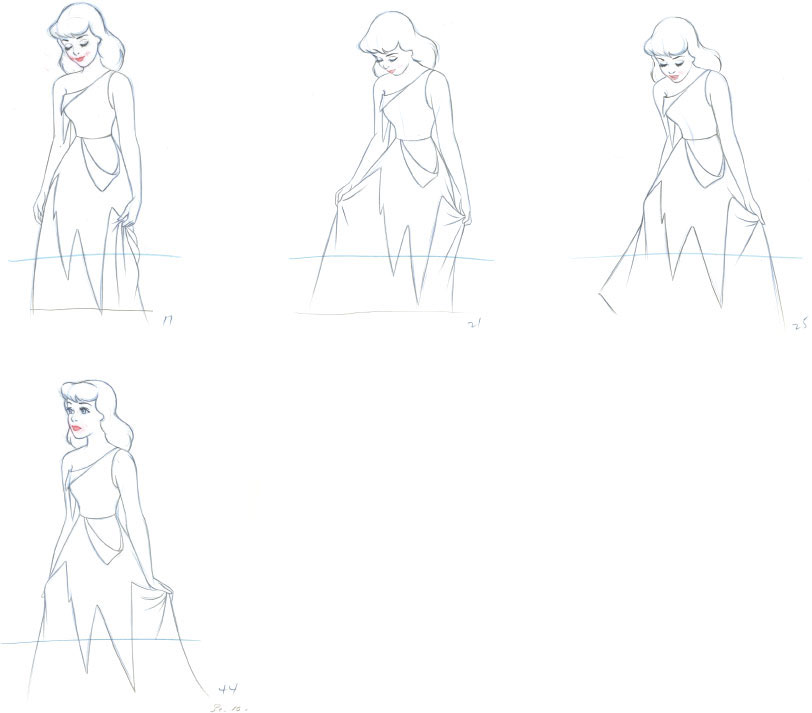

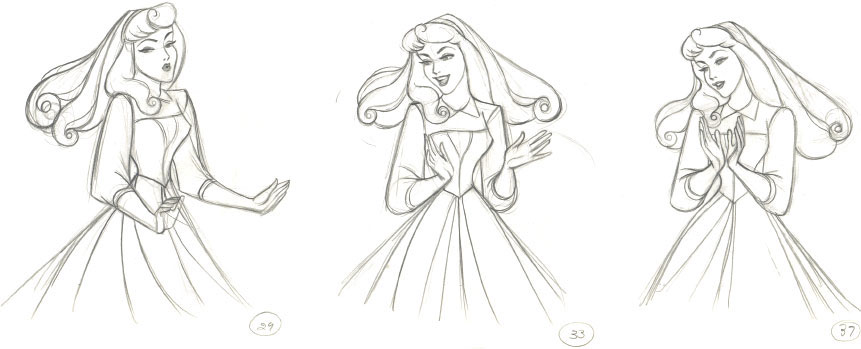

1959

AURORA

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 12, Sc.17

“Everything is so wonderful, just wait ’til you meet him!” Aurora tells the three good fairies that she is in love, and what better way to express her emotions than twirling around in dance-like fashion? Marc made use of two elements that help the animation appear graceful and fluid. Aurora’s long, curly hair is beautifully designed as it flares out during the turn around. The same can be said for the many lines defining folds on her skirt. It is interesting to note that as the character directs her attention from screen left to right, her upper body is leading the motion. The lower body moves slightly in the opposite direction for balance. Even during her acting scenes, Marc always maintained an element of elegance and fluency.

© Disney

© Disney

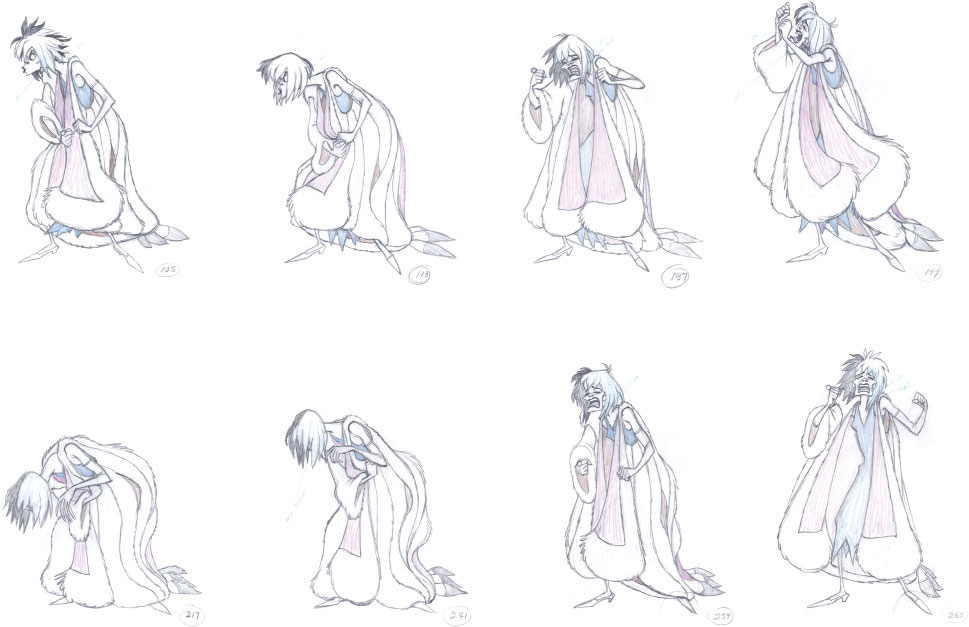

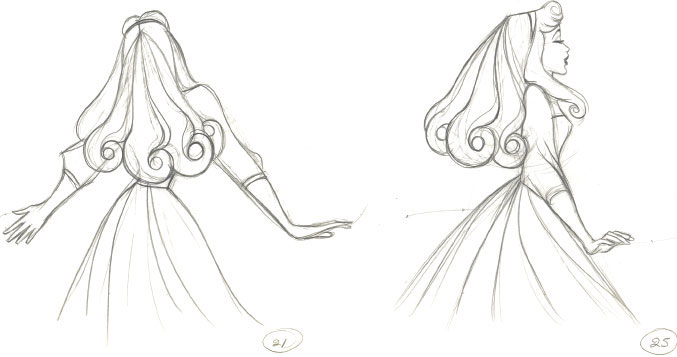

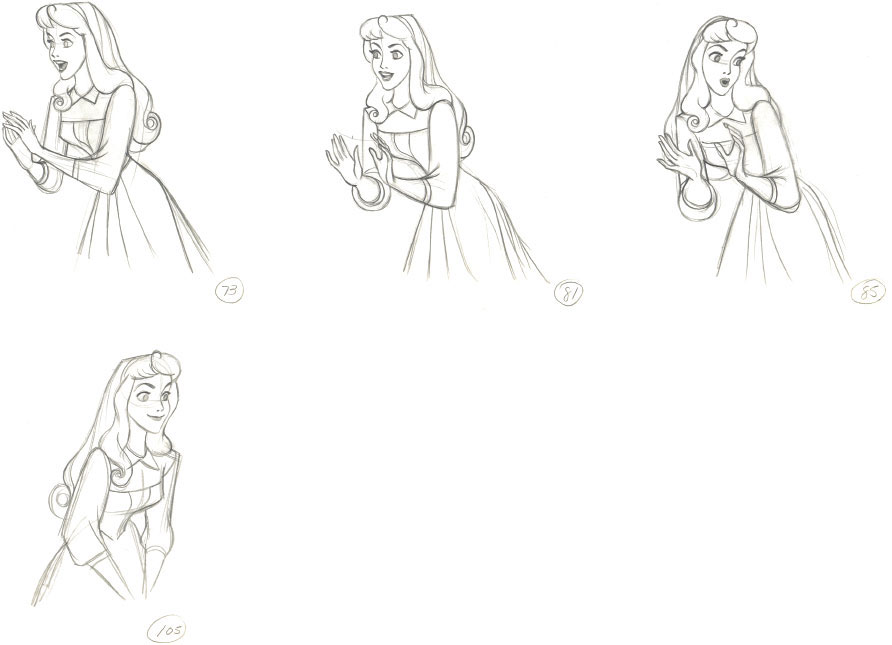

1959

MALEFICENT

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 18, Sc. 67

Maleficent leaves the dungeon, in which Prince Phillip is being held captive. She locks the door with a key and puts it into her pocket. “For the first time in 16 years I shall sleep well,” she tells her raven. This is a sequence of stunning drawings reminiscent of elegant fashion illustrations. The main motion here is the key traveling from the door lock into Maleficent’s pocket. The audience follows this move very clearly since her overall action is very slight and gradual.

In scenes like this one, it must have been a challenge to keep the raven firmly placed on Maleficent’s shoulder, since her oversized collar could get in the way.

But, Marc always manages to stage the raven convincingly with the collar either in front or behind him.

© Disney

© Disney

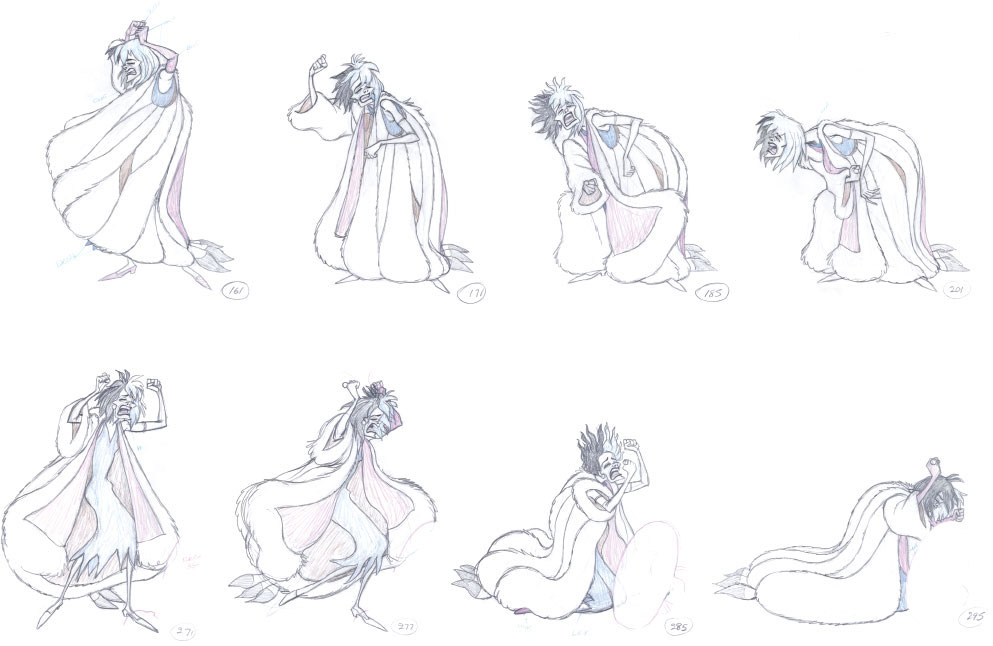

One Hundred and One Dalmatians

1961

CRUELLA DE VIL

TOUCH-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 16, Sc. 182

Cruella gets her comeuppance in her final scene of the film. In trying to push over the truck in which the Dalmatians are hiding, her car collides with Jasper and Horace’s vehicle. All three end up down an embankment among car wreckage. “You idiots! You…you fools! Oh, you imbeciles…ah, ha, ha…” Jasper responds: “Aw, shut up!”

Marc was able to turn Cruella’s desperate finale into a highly entertaining scene.

He drew her looking exasperated and disheveled. Yet ultimately there is something hilarious about the way her torn fur coat barely hangs on to her body. Every frustrated move she makes is being enhanced by the follow-through action of her lower coat.

The scene might have been Marc’s final piece of animation, and it is a masterpiece. Drawing and motion look grotesque and bizarre, but appealing at the same time.

© Disney

© Disney