“Walt Disney never talked down to an audience, instead he always tried to bring you up to his level.” Those words by animator Eric Larson were directed at young newcomers to the studio during the early 1980s, people like Mark Henn and Ruben Aquino, as well as this author. Eric tried to make it clear to us that top quality work was key to any Disney animated production. He talked about having high standards in your work as a good rule to live by and a good way to express yourself as an animator. In so many ways Eric was much more than an animation teacher; he represented the Disney philosophy of bringing things to life in a believable, genuine way. There were certainly useful tools of the trade that were a big part of his curriculum, but no matter how frustrated we occasionally became with our early attempts to animate—poor timing and the lack of weight showed our inexperience—a talk with Eric always left us with a feeling that this is the greatest art form in the world. We all knew what a privilege it was to be a part of a group of artists that was encouraged to continue the traditions of Disney animation under the guidance of one of the medium’s masters.

This quote from one of Eric’s lectures exemplifies his affection for animated filmmaking:

Animation is a form of communication, and therefore when you’re animating you are making a statement: a statement about the character, the story, the feelings and emotions, actions, personalities, archetypes, etc. If you want the audience to get involved in the story, connect with the character, and feel the emotions needed to sympathize and relate to that character you must make a positive statement. To make a positive statement you have to know your characters and their personality, have a devotion to your craft, know how to use your art to express the statement you want to make, apply feelings and emotions that are strong and real to a fantasy story, and most of all have sincerity. If you don’t have feelings and emotions for your character, how can it even be possible for the audience to?

Young Eric Larson originally pursued writing with the hopes of becoming a journalist. But he also enjoyed drawing, and when in the early 1930s word got around that Walt Disney was hiring artists Eric applied and was hired as an in-betweener. He did assistant work on short films like Two-Gun Mickey, Mickey’s Service Station, and the groundbreaking The Tortoise and the Hare, which featured innovative action scenes by animator Ham Luske. At one point the Hare plays tennis with himself, speeding back and forth on the tennis court.

Eric Larson was very much impressed by the way Ham Luske timed his actions. For very fast motions speed lines were drawn to simulate a motion blur. It might have been slightly overdone, but this experiment succeeded in creating fast but smooth-looking animation.

© Disney

Luske had to work hard to make his drawings look good, and to make them perform in a way that felt believable and genuine to him. Eric was not a natural draughtsman either and often struggled to catch up with animators like Milt Kahl or Marc Davis, whose work was always beautifully drawn and showed a flair for strong design. But to Eric the struggle was worth the effort to get a performance on the screen. And it was certainly not beneath him to ask superior draftsmen at the studio for help in order to make his scenes look better. This kind of teamwork was very much encouraged by Walt Disney himself, who knew that his artists could learn from each other, particularly when the studio started work on their first feature-length production Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. It was at that time that Eric got his big break. At the suggestion of Ham Luske, Eric was promoted to full-fledged animator. He joined Milt Kahl in animating large groups of forest animals who interacted with Snow White in many scenes. This was a hugely labor-intensive assignment. To synchronize the movements of several deer, chipmunks, and bunnies has more to do with choreographing a ballet than animating your average scene. Real animal motion needed to be studied so that the animation would look natural enough next to the realistic character of Snow White. Eric was happy with most of the results; however, he felt that the deer—with their flour-sack bodies—could have benefitted from a dose of strong anatomy.

Synchronizing so many woodland creatures was more like choreographing a ballet than animating a scene.

© Disney

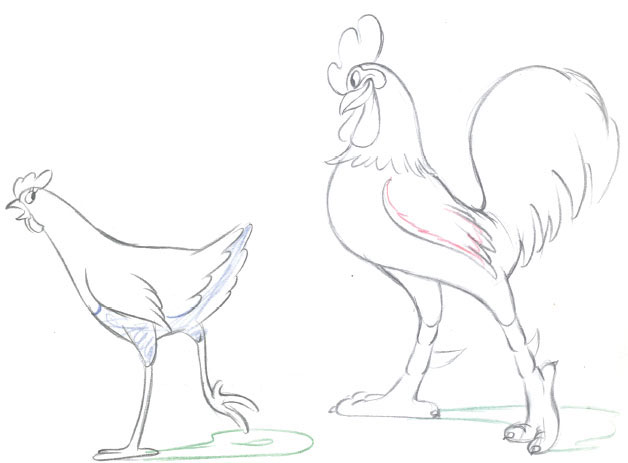

Rooster and hen in the middle of a romantic duet.

© Disney

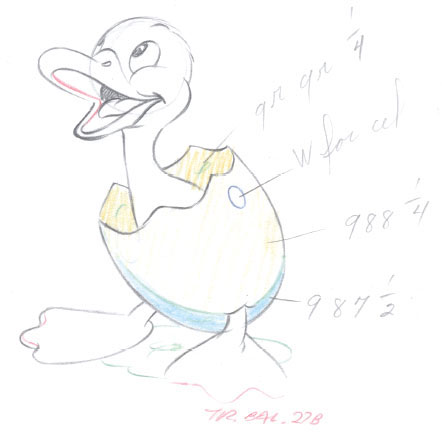

Before getting involved in Disney’s second animated feature, Eric continued working on charming, cartoony animal characters for short films like Farmyard Symphony and The Ugly Duckling. The Disney style of the late 1930s and 1940s had a soft, cuddly quality, and Eric felt very comfortable with this relatively simple approach to drawing and constructing animated characters.

The Ugly Duckling is born.

© Disney

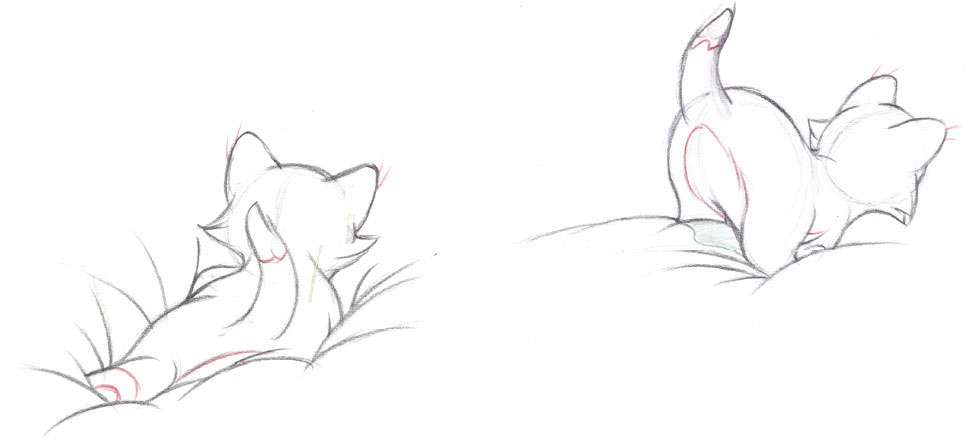

While these farm animals were designed in a simple way to tell a short story, Eric’s next character needed to have a much more developed personality, after all he became one of the main characters in the film Pinocchio. Figaro’s early designs were a caricature of an adult cat, but Eric much preferred to portray this mischievous, but lovable character as a kitten. His feline moves feel so believable because they are based on real cat motion and then caricatured in the most loving way. Figaro’s human attributes and expressions have roots in a former Larson family member, Eric’s four-year-old nephew. Kids that age show typical characteristics of misbehavior and mood swings but also affection for their parents, and Figaro’s personality fits all of these attributes. Then there is a classic brother–sister relationship between him and the goldfish, Cleo. That kind of character pairing offers rich and contrasting situations that help to bring these youngsters to life. Eric produced some beautiful pantomime animation in an early section of the film. Geppetto and Figaro have just settled for the night into their respective beds, when the old woodcarver decides to make a wish. Geppetto asks Figaro to open the window so he can ask the wishing star for Pinocchio to become a real boy. Eric saw great potential in the way Figaro could react in this situation. He first looks up to Geppetto with an upset “Now what?” expression, then tosses his blanket with each foot at a time before tumbling out of bed in the direction of the window. He hops on to Geppetto’s bed and crosses over a soft bedcover. Figaro’s body reacts beautifully to each surface he comes in contact with. Strong squash drawing is used when he first tumbles out of his bed and hits the hard wooden floor. By contrast his legs sink deeply into Geppetto’s bedcover, which communicates the weight of the cat as well as how cushy the blanket is. All this adds a ton of charm to this little character, who Eric obviously adored animating.

Figaro crossing a soft bedcover in the film Pinocchio.

© Disney

A very different type of animation was required for Eric’s other assignment on Pinocchio. Walt asked him to take over the marionettes that danced on Stromboli’s stage and interacted with Pinocchio. These characters were not supposed to look alive, since their actions were manipulated by offstage humans. Eric knew that in order to make the audience believe that these puppets were made out of wood, a different approach to their animation was needed. Absolutely no squash and stretch was applied when their bodies hit the floor or made contact with each other. Wood is a very hard material, and distorting their volumes would have made them look like living characters. Eric synchronized the animation perfectly to the musical beats of the song “I’ve Got No Strings,” and the result is an utterly convincing performance with marionettes.

A unique approach was required to make audiences believe the marionettes were made out of wood.

© Disney

Figaro’s actions showed real feline motion while the stage puppets acted with no inner lives at all. Eric Larson’s next assignment for Disney’s Fantasia called for a fantastical and imagined type of movement, since the characters were centaurs. They appeared in the Beethoven/“Pastoral” sequence. This classic combination of horse and man presented a challenge in terms of body rhythm. How would the human upper body react to the motions of the lower horse anatomy and vice versa? Animator Fred Moore had designed these fantasy creatures in a simple, roundish, and cartoony way. So drawing them didn’t present major difficulties, but making them move turned out to be the real challenge. That important unified body rhythm was never established in motion, and the end results look stiff.

Years later Eric talked to us students about the fact that he still felt embarrassed by his animation of those centaurs. “The girls look OK for the most part,” he said, “but the men never come to life properly.”

Eric Larson questioned the quality of the centaurs’ design as well as his animation.

© Disney

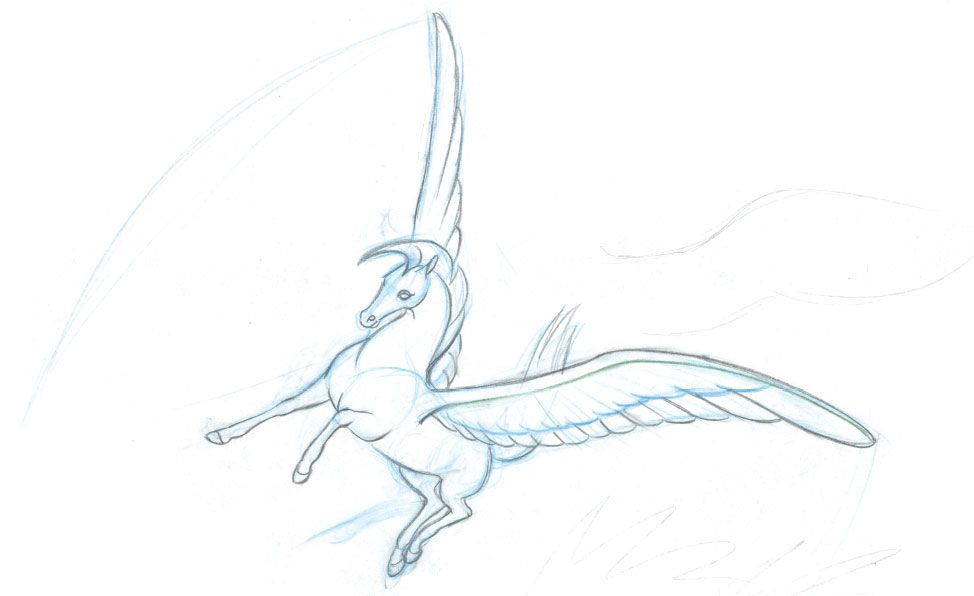

Eric had more success with the flying horses in the “Pastoral” section of Fantasia.

© Disney

Eric redeemed himself, however, when he also animated several scenes with members of the Pegasus family in the same Pastoral section of Fantasia. The graceful movements of a flying horse needed to be invented as well, but Eric found this combination of bird and horse a much more pleasant assignment than the centaurs. There is great elegance in the way these huge creatures land softly in the water before their wings are turned backward to simulate floating swans.

After animating mythological flying animals, Eric turned to a “real” bird for the film Bambi. He developed and drew Friend Owl, a character he much identified with. Intentional or not, Eric’s own gentle personality greatly influenced this owl’s character, who often shows fatherly affection towards the other forest animals. That is, until spring season arrives and the calm of the forest is interrupted by noisy birds and other “twitterpated” animals. His attempt to quiet everybody down with a loud warning is unsuccessful, and he flies off in search of a more peaceful part of the woods. What follows is an unexpected, but very entertaining performance that mocks the birds’ courtship behavior: “Tweet, tweet! Pain in the pinfeathers I call it.”

We find out that Friend Owl has a somewhat zany sense of humor.

Larson’s own gentle character and sense of humor are reflected in the personality of Friend Owl.

© Disney

The character was voiced by actor Bill Wright who sounds like everybody’s favorite grandfather. And that is exactly who Eric Larson became in his later years, a kind and patient mentor with an edgy sense of humor.

After Bambi and for the rest of the 1940s The Walt Disney Studios focused on the production of short films. Eric animated on several films with Goofy such as Tiger Trouble and African Diary.

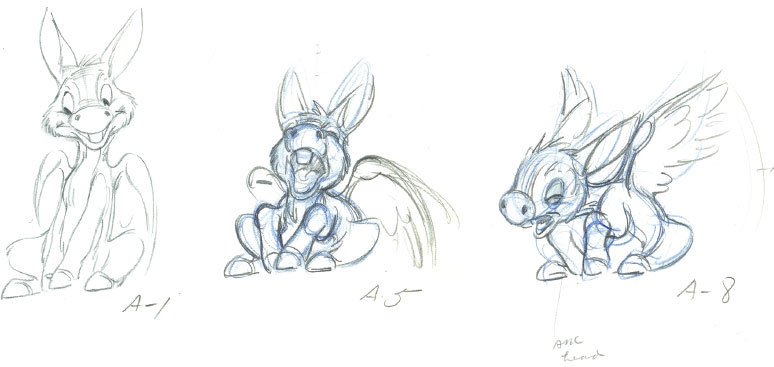

The star of the short The Flying Gauchito was Burrito, a donkey with wings, and Eric again ended up drawing a Pegasus-like creature. Frank Thomas supervised the character’s animation, and Eric was a natural choice to help out because of his experience with flying horses for Fantasia.

Eric researched a range of facial expressions as well as simplified horse and partial bird anatomy.

© Disney

By now Eric had become somewhat of an expert in animating birds. When work began on the short film Peter and the Wolf, he was cast on Peter’s eccentric little bird friend Sasha. This character’s emotions were always strong and extreme. When he first sees Peter, Sasha is very happy, and when he encounters the Wolf, he is very frightened. His movements are extremely fast and snappy. Eric would hold a pose for about ten frames, just enough to register, before quickly moving on to another pose. This kind of timing gave Sasha a nervous, energetic quality. He also comes across as enthusiastic and adventure-loving. After all, his friend Peter surely won’t be able to track down the Wolf by himself.

Eric told his students later that at least eight frames of film are needed for any pose to read on the screen. Anything less than that would make the pose disappear in action.

A small character with big emotions.

© Disney

Snappy timing was again needed for the main characters in the film Song of the South. Eric saw a lot of potential in developing rich personalities based on the voice recordings, which suggested a strong contrast between the slow bear, the fast fox, and the smart rabbit. Eric animated a scene in which Brer Rabbit is caught in the fox’s trap. This is a very awkward position, and any acting is restricted to head turns and small hand gestures. But Eric still managed to portray the rabbit with the confidence that he could talk Brer Bear into freeing him.

Brer Habbit displaying unlimited confidence despite limited movement.

© Disney

Clips from this film were often shown during Eric’s classes on action analysis. The animation is often at a very fast pace, but all poses and expressions read clearly. It taught us students just how far you can take personality animation in terms of speed and energy.

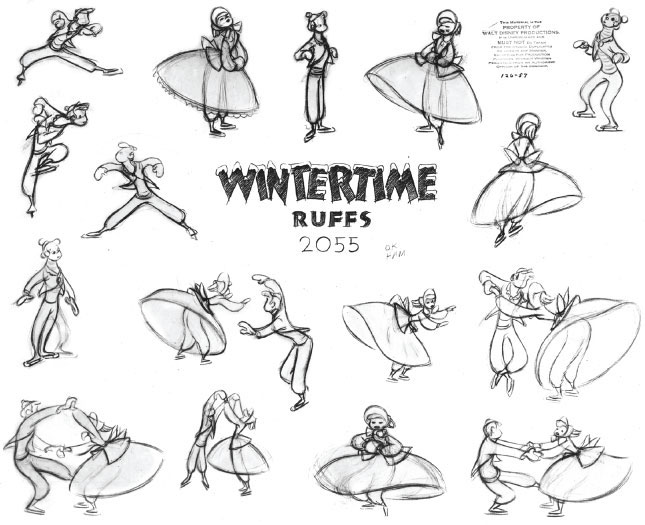

Just like on Song of the South, Eric Larson was one of a few supervising animators on the 1948 film Melody Time, which included several short films for a feature-length presentation. Eric did significant animation work on a couple of titles. One of them, Once Upon a Wintertime, is a simple love story, featuring Joe and Jenny, as they skate on the ice within a Mary Blair-inspired environment.

Stylized designs allowed for smooth, fluid animation.

© Disney

The two lovers get into an argument and almost separate before encountering the danger of breaking ice. But all ends well. Their character design is simple and graphically reminiscent of the fluid, rhythmic lines of caricaturist Al Hirschfeld. The animation reflects those design choices. Joe and Jenny move elegantly on the ice like professional skaters. Eric relished working on them, he found that their simple lines and shapes were easy to draw, which freed him up to focus on the animation. Animators who have difficulties drawing their characters will often produce stiff animation, because of the struggle they go through in putting a good pose or expression on paper.

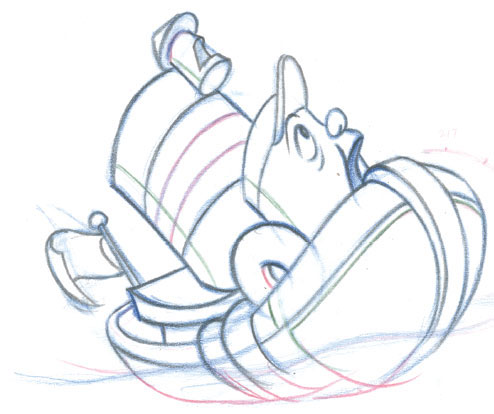

Melody Time included another short film featuring beautiful Eric Larson animation. Little Toot is the name of a little tugboat with a mischievous, childlike personality. Eric said that when animating he thinks about those human qualities first, the fact that this character is an inanimate object is of a secondary nature. The story is again very simple: Because of his “show off” behavior Little Toot gets into trouble and is eventually banished out to the open sea. A storm rolls in, causing trouble for a vast liner nearby. After Little Toot pulls the huge ship to safety he is hailed a hero. Eric needed to bring the character’s emotions across without the use of arms and legs. The main shape of the boat functions as a torso, and the cabin is drawn as a human head. Yet Eric was able to portray childlike attitudes by having the little boat hopping on the water, leaving splashes behind. Little Toot would wiggle his rear before moving forward at great speed. Moves like these are convincing because they are reminiscent of a happy kid or of a dog anticipating a jump. This was part of Eric’s philosophy; personality animation needs to have roots in the artist’s observation of real-life situations.

Little Toot manages to demonstrate childlike qualities, despite having no arms or legs.

© Disney

Eric Larson had to shift gears between a fantasy character like Little Toot and a realistic human like the title character in Cinderella. Studying live-action footage carefully was the basis for subtle, believable performances. Eric shared the duty of supervising the title character’s animation with colleague Marc Davis. They both drew key personality scenes throughout the film, but it was Eric who was responsible for introducing Cinderella during the opening scenes. A few of her animal friends, including birds and mice, wake her up, and because she interacts with them in a playful, teasing way, Cinderella is instantly likeable. She sings “A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes,” which signals that she has not given up hope, even though her life has been reduced to the role of a kitchen maid. During the song she undoes her pigtails in a feminine and natural gesture.

Cinderella is instantly likeable in the opening scene.

© Disney

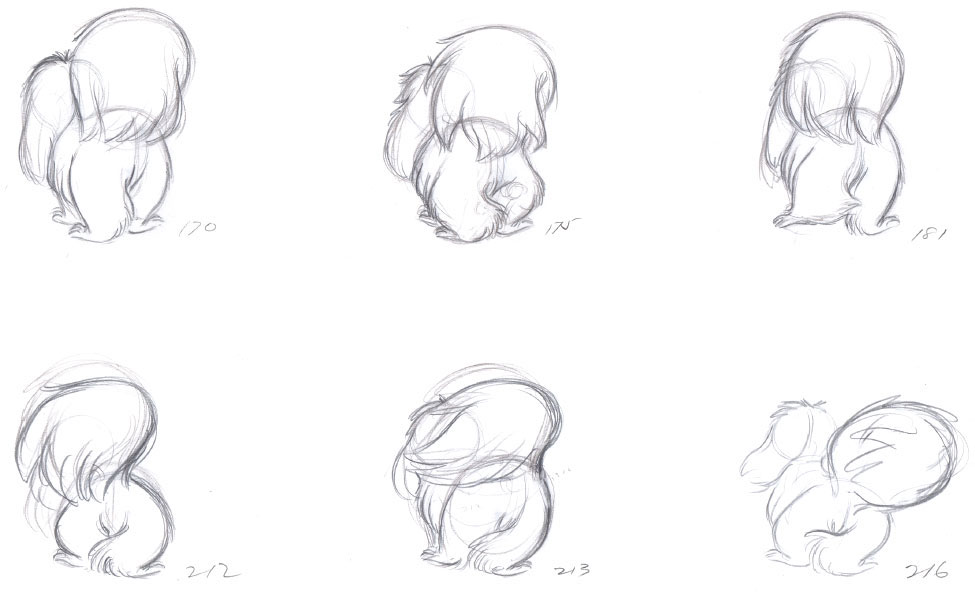

Animating hair convincingly is not an easy thing to do. Unlike in computer animation, only a few pencil lines define its shape and movement. Eric enhanced the motion of Cinderella’s hair by making it swing further, particularly during quick head turns. This overlapping action complements the character’s principal movements in a natural way.

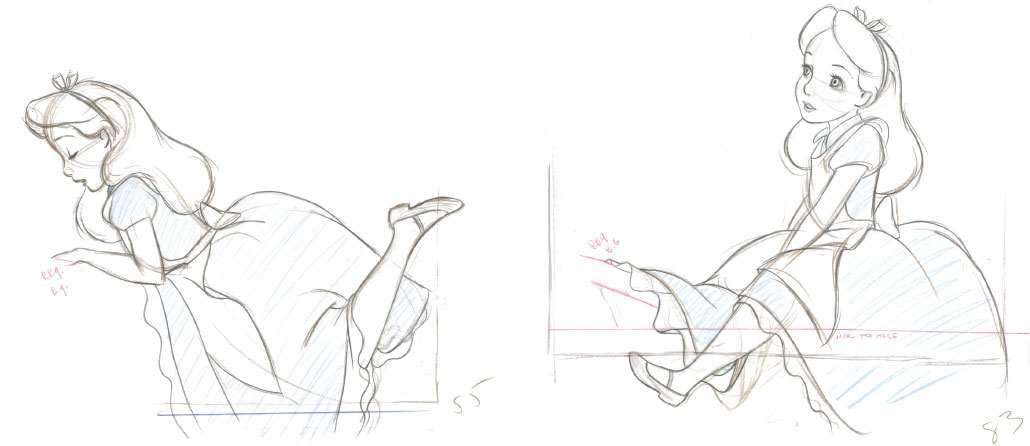

The film made after Cinderella presented a much younger heroine. But Alice from the movie Alice in Wonderland was also designed in a realistic way, and animators based their work on live-action reference. Eric was again asked to animate the title character’s introductory scenes. Alice sits on a low branch of a tree listening to her sister, who reads from a history book. We understand instantly how bored Alice feels because she doesn’t pay much attention. Instead she plays with a floral wreath, placing it on the head of her cat Dinah. These scenes are carefully drawn and help establish Alice as a real girl, who lives in her own colorful world. From a technical point of view, Alice’s wide dress with its many folds presented something of an animation challenge. Every move she made needed to be complemented by the right kind of fold action. If not animated correctly, her dress would look too light or too heavy. But because Eric had earlier handled scenes with Cinderella and the Prince dancing, he already had a certain amount of experience moving folds on the fabric of a dress.

The animation for Alice was based on live-action reference.

© Disney

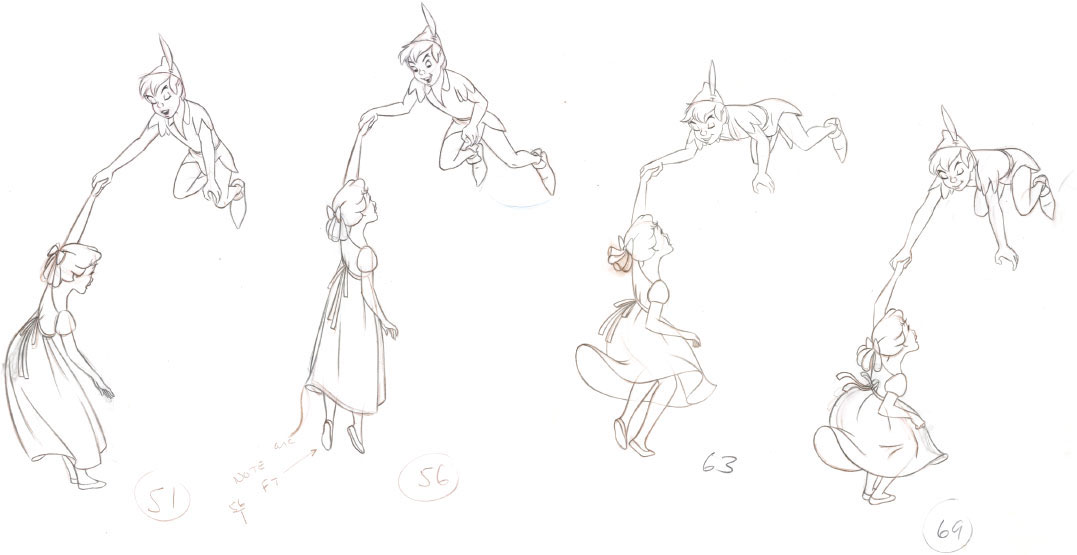

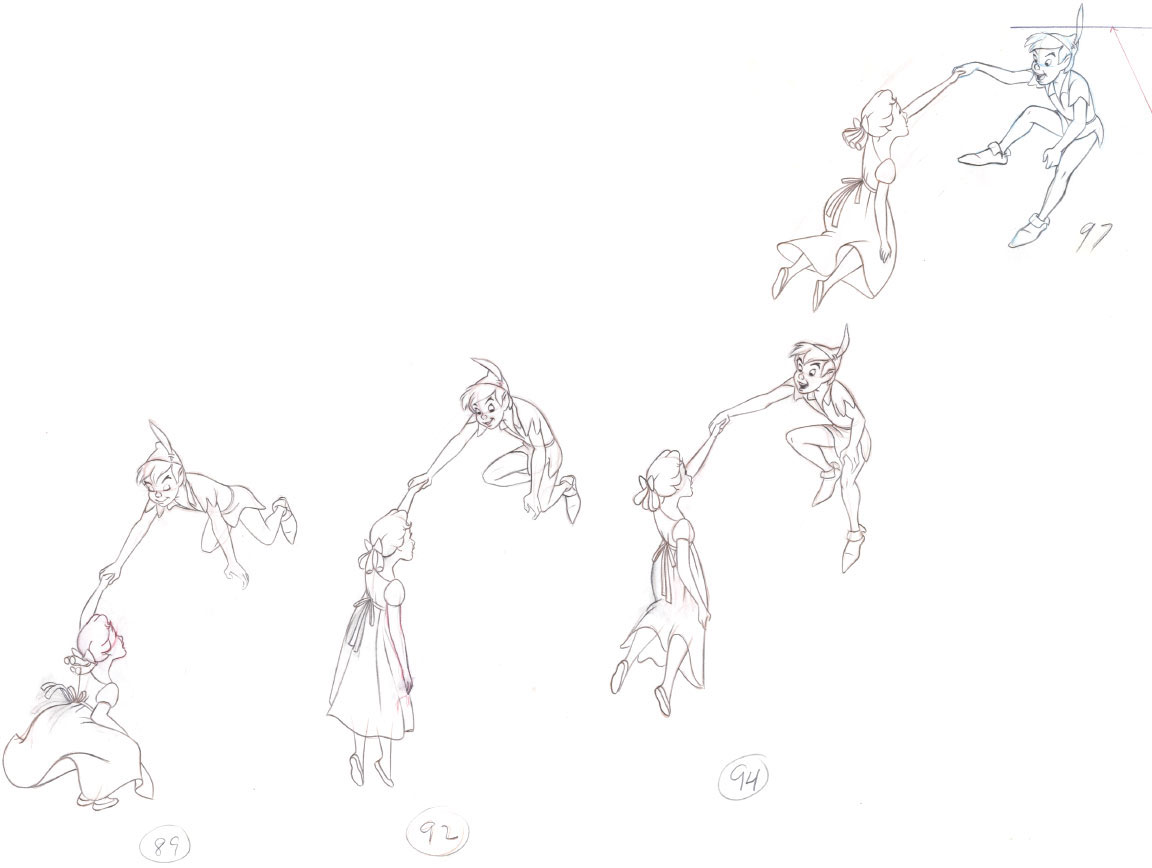

The trend to animate characters in opening sequences continued for Eric in the film Peter Pan. He drew scenes with Peter when we first see him at night on the rooftop of the Darling house. Kept in silhouette, his introduction is very effective, and Eric made him move like a dancer here. When a pose is held, it reads clearly. When Peter is in motion, it has a very fluid effect.

Peter Pan promises the Darling children a flight to Never Land.

© Disney

Milt Kahl handled the following scenes inside the nursery. Eric takes over when Peter teaches Wendy, John, and Michael how to fly. The technically complex animation required for the flight over London and on to Never Land is Eric’s work as well. The children fly in perspective into camera and away from it while involved multiplane camera moves enhance their flight path.

Eric confessed later that this was hard work, but he was proud of the sequence because watching it gave you a thrill.

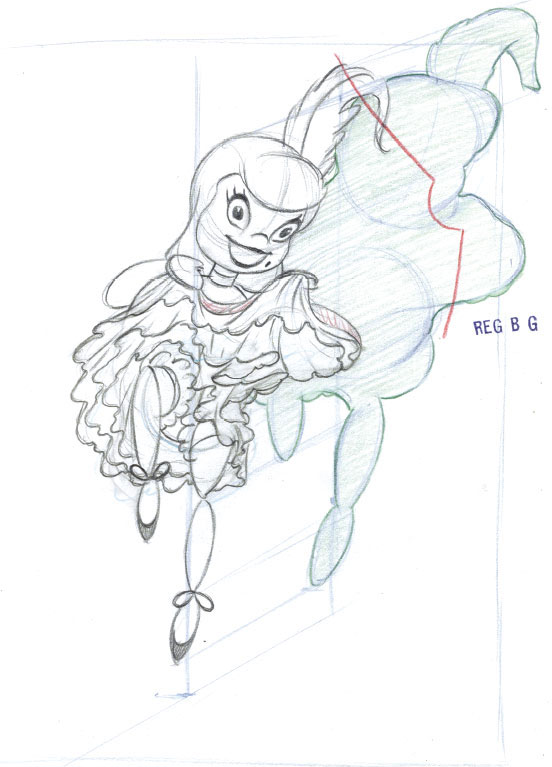

Milt Kahl helped Eric to keep Peter Pan on model by providing accurate key drawings for Eric’s scenes. When Milt years later was asked by a reporter to comment on the film that followed, Lady and the Tramp, he said: “Well, the best thing in it is Eric’s dog Peg”—a high compliment from the studio’s top draftsman. Eric himself always blushed a little when he related the fact that he based Peg’s provocative moves after singer Peggy Lee, who voiced the character. The film features many great dog personalities, but Peg’s performance is simply outstanding. Her character, with the past of a “worldly” showgirl, was a novelty in a Disney film, and Eric took full advantage of this new kind of material. During the song “He’s a Tramp,” Peg sings some of her lines over a raised shoulder with a Veronica Lake hairdo. She walks away from the camera and the spotlight as her tail and hip moves are greatly exaggerated.

A beautiful rough animation drawing showing Peg in mid-song.

© Disney

Drawing, movement, timing, and appeal are perfect. Eric had become very comfortable animating all sorts of animals, and all that know-how helped turn Peg into an unexpected star of the film.

Walt Disney was so impressed with Eric’s work on Lady and the Tramp that he offered him the chance to co-direct the next ambitious feature, Sleeping Beauty. Eric took over the romantic boy-meets-girl sequence, with the goal of turning it into one of the most beautiful pieces of animated filmmaking ever. Most people would agree that Eric achieved that goal. Unfortunately it also turned out to be one of the most expensive sequences ever produced at the studio, and Walt was not pleased.

In order to achieve an enchanting forest setting for Aurora and Prince Phillip, Eric asked his layout and background artists to use the studio’s multiplane camera extensively. Several individual painted layers of trees, bushes, and branches were photographed at various distances under the camera to create an illusion of real depth. Scenes like these were very effective in taking the audience into the world the characters are inhabiting, but they were also time-consuming and very costly to produce.

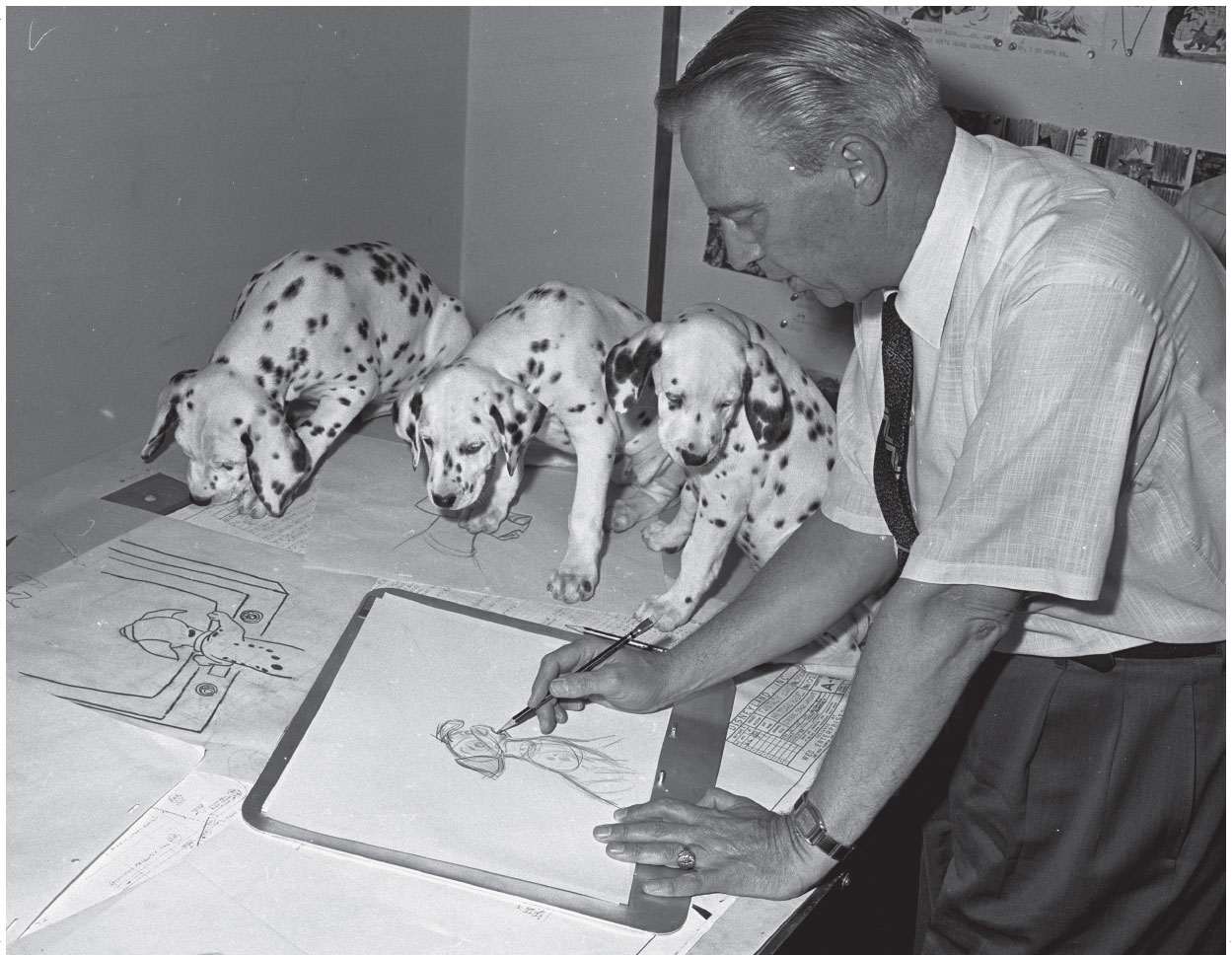

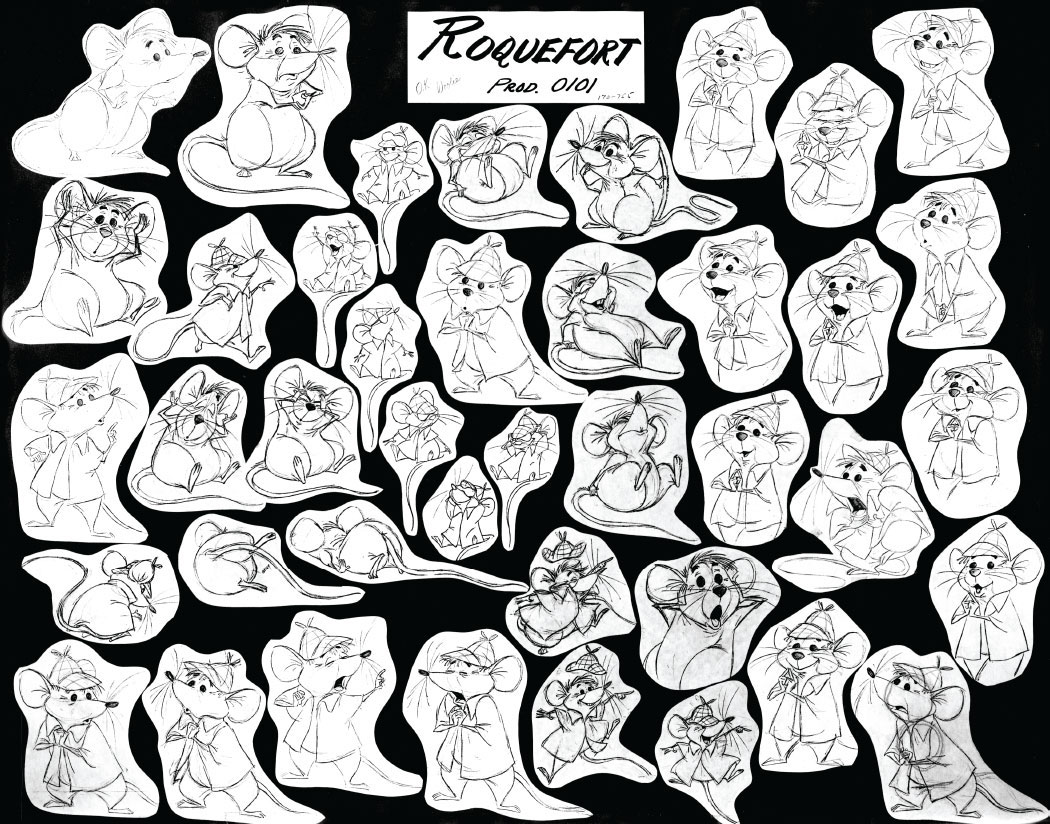

Eric went back into animation for the films that followed, One Hundred and One Dalmatians, The Sword in the Stone, Mary Poppins, and The Jungle Book. He didn’t get the chance to develop any characters for these films in the way he had done in the past. His animation on the Dalmatian puppies, Sir Ector, Wart, Bagheera, and Mowgli is good, but lacks the charm and inventiveness of his earlier work. The final character Eric could call his own is the little mouse Roquefort in the film The Aristocats. Suddenly that Larson touch was back, and Eric turned this unusual assignment of a mouse who is friends with a family of cats into a most charming character.

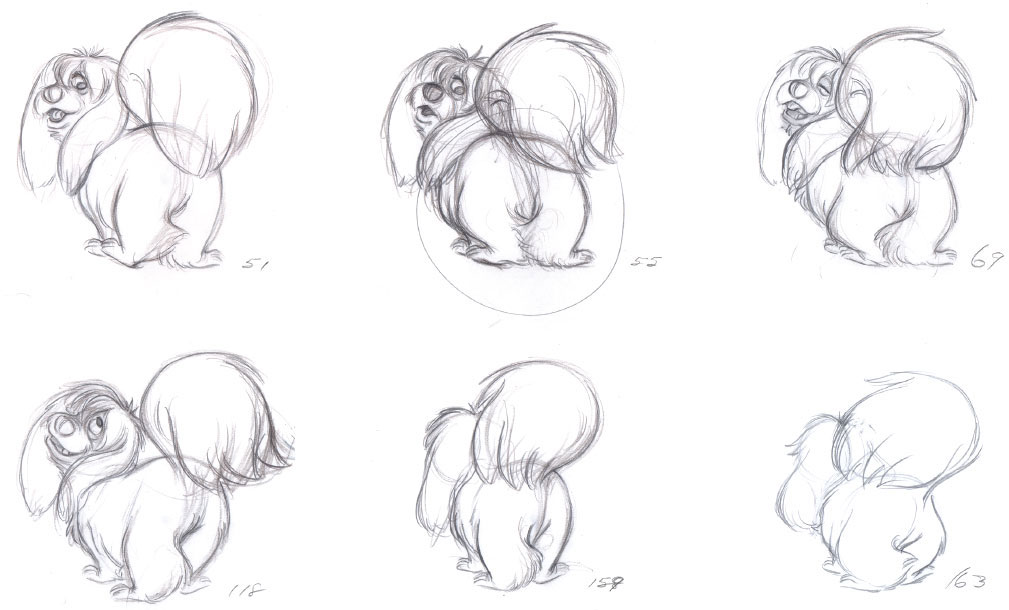

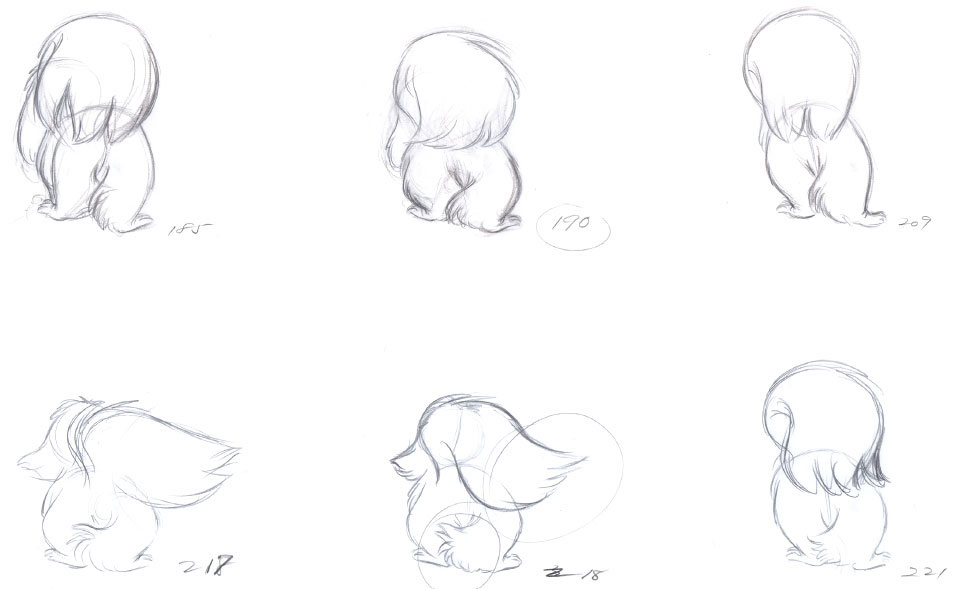

FACING PAGE Roquefort’s model sheet, made up of Eric’s rough animation drawings.

© Disney

Favorite scenes include Roquefort sharing a meal with Duchess and the kittens. He brings along a huge cracker, dips it in the cats’ warm milk and munches away, making a lot of noise.

When he finds out that the cats have been kidnapped, he puts on a Sherlock Holmes costume and sets out to find them. Sterling Holloway voiced Roquefort beautifully, and Eric maintained quick mouse-like movements in the animation.

While work on The Aristocats continued, the studio started to realize that its animation department consisted mostly of artists who were getting near retirement age. It was decided that, in order to guarantee the future of Disney animation, new, young talent had to be found and trained in the classic techniques. Eric Larson turned out to be the perfect head of this new training program, which was structured in the following manner: Eric gave lectures on a regular basis on all topics regarding the production of Disney animation. He also worked with each trainee individually and helped them to express themselves in their animated scenes. Perfect motion was not good enough; character animation at Disney had to include the artist’s individual point of view. Eric Larson’s final contribution to the art of animation was enormous. He made sure that a new generation of animators saw the significance, the potential, and the challenge of Disney personality animation. Without his important involvement as a teacher and motivator, the film medium that Walt Disney had pioneered for many decades would have died in the 1970s.

1945

THE FLYING GAUCHITO

GAUCHITO AND BURRITO

ROUGH ANIMATION

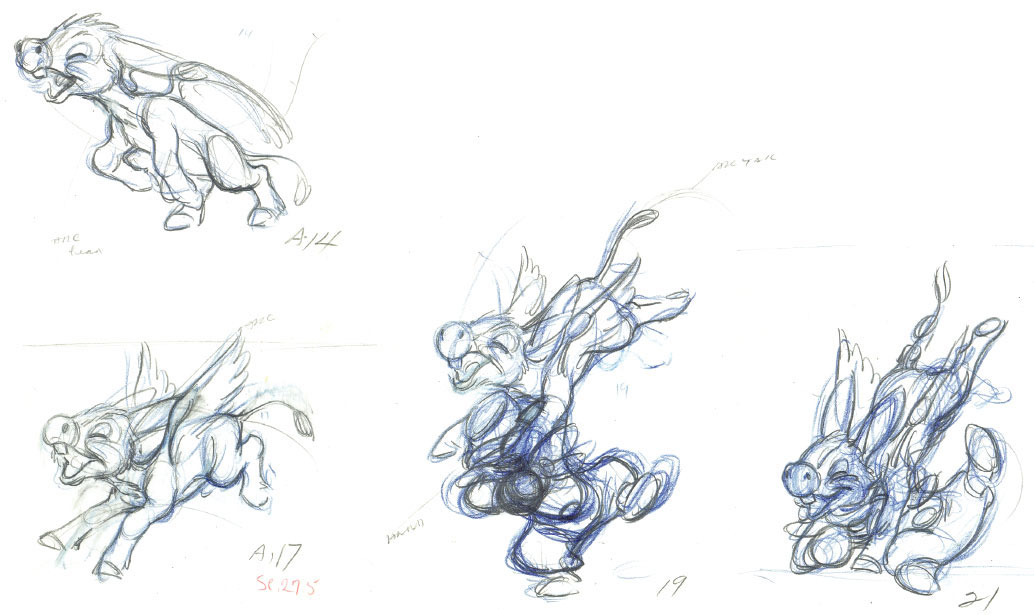

Sc. 37

During a bonding moment the Gauchito offers his winged donkey a sip of his mate, a South American drink. The Burrito jumps on the kid and both get entangled as they roll backwards. The final pose shows the donkey having a drink through a straw, the Gauchito beside him. To keep the action from looking complicated, Eric simplified the poses during the tumble. As the two characters straighten up, everything is back in place, including the mate. Throughout the scene, Eric defines the Burrito’s anatomy very thoroughly.

After having worked on Fantasia’s flying horses, he was ready to apply that knowledge to a flying donkey, and make it look believable as well as entertaining.

© Disney

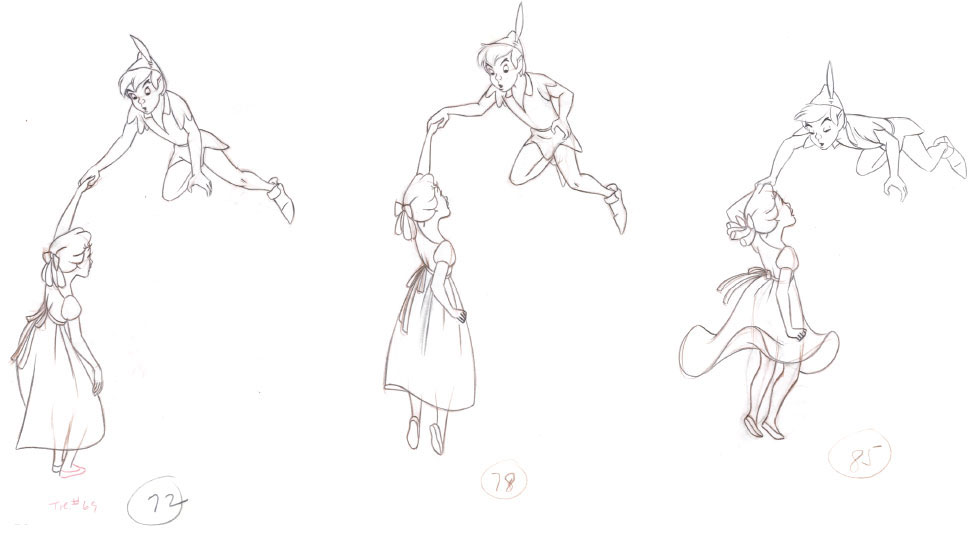

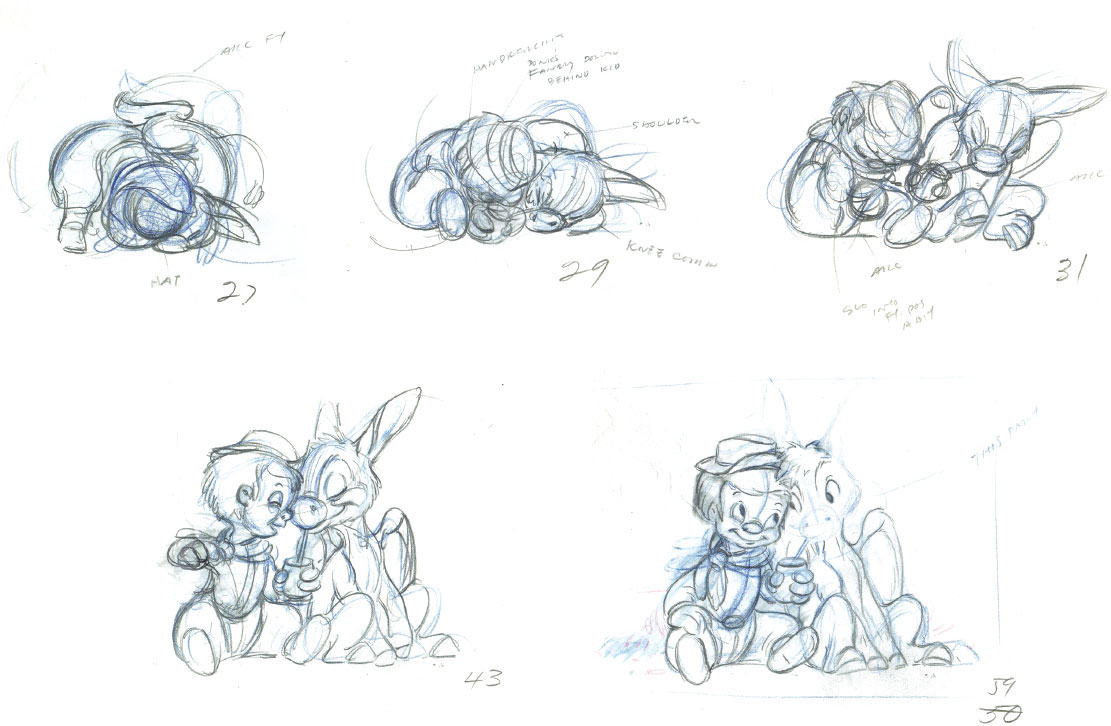

1953

PETER PAN AND WENDY

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 2.1, Sc. 52

During a flying lesson, Peter Pan tries his best to get Wendy airborne. Not until the third try does Wendy take to the air. In itself this is a powerful statement regarding animated characters. Just as in real life, things often don’t work the first time around, it takes repeated efforts. This scene would feel very boring if Peter had succeeded the first time around. But by failing a couple of times, a sincere human touch is added to what otherwise would have been just an ordinary continuity scene without much personality.

On a technical level, the overlapping motion on Wendy’s loose skirt helps to give the scene a beautiful flow and rhythm.

© Disney

© Disney

1955

PEG

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 10, Sc. 81

During the dog pound sequence, Peg struts toward the back of the cell, singing: “And I wish that I could travel his way… wish that I could travel his way…”

Eric famously studied singer Peggy Lee’s walk and applied her sashaying quality to this dog character, whose personality is somewhat seductive. He exaggerated the hip movement from left to right, each time one rear leg contacts the ground. Since Lee emphasized the word “way” several times during her song, Eric flairs out Peg’s tail in order to visually accentuate these beats. This is a beautiful character walk for a dog with a showgirl past.

© Disney

© Disney

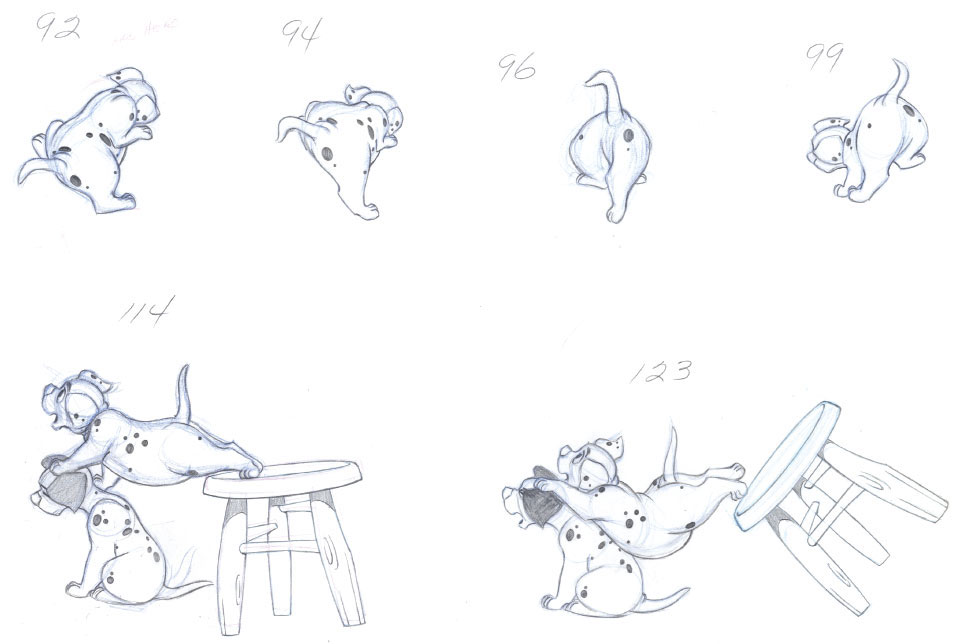

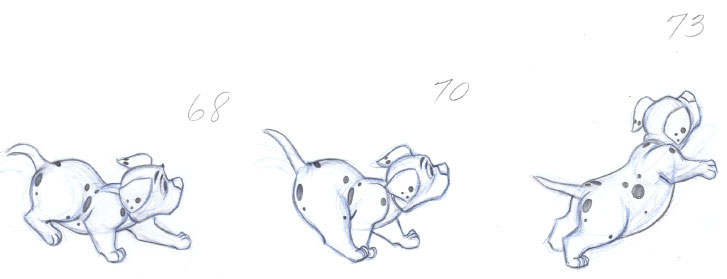

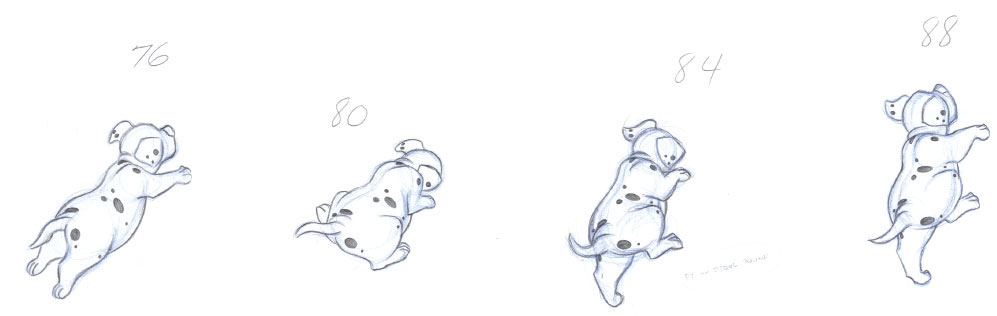

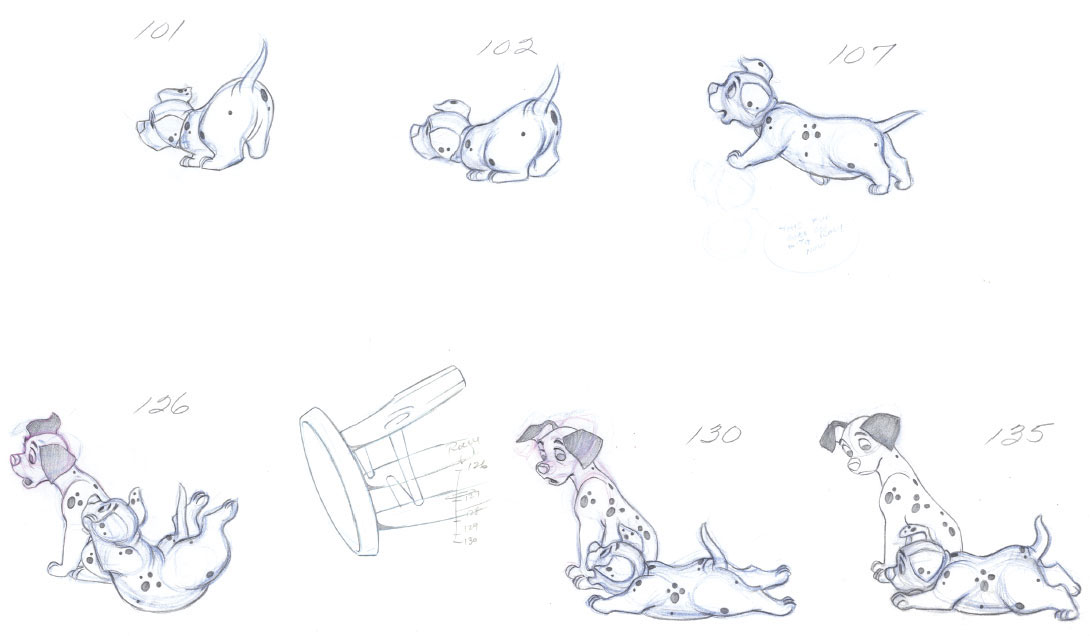

One Hundred and One Dalmatians

1961

ROLLY

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 15, Sc. 46

After the cows in the barn generously offer their milk to the starving Dalmatian puppies, Rolly tries desperately to get close to one of the udders. After a few failed attempts he manages to climb on to a stool. By leaning forward and balancing himself on Lucky’s head he almost succeeds. But instead his weight drags him down and he falls on his belly—still no milk. Eric wanted to show that Rolly is a little clumsy, so on his way to the top of the stool, his right rear foot slips, but he manages in the end. Little mishaps like this help to create a character whose efforts aren’t always perfect. It gives this scene texture, but also more interest, because a little Dalmatian who struggles is more enjoyable to watch than one who just goes through the motion flawlessly.

© Disney

© Disney

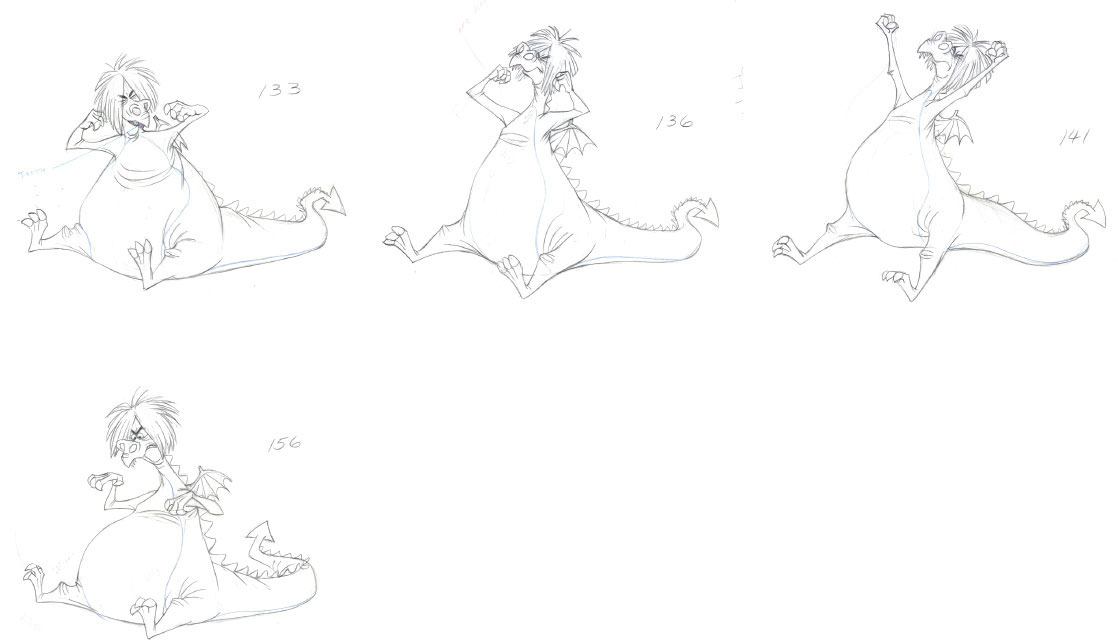

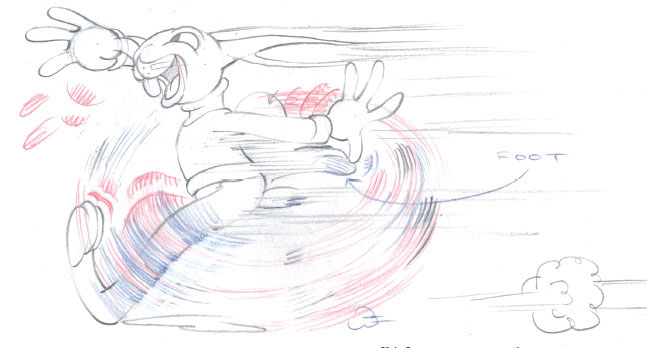

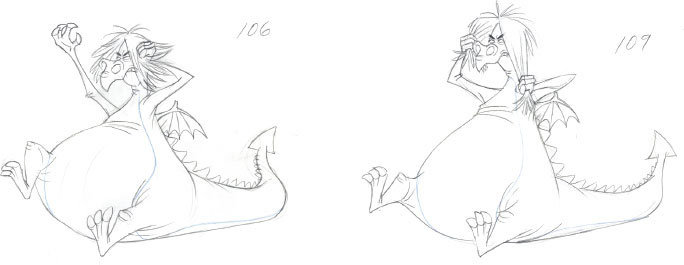

1963

MADAME MIM AS DRAGON

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 10, Sc. 144

The duel of the wizards is over, and Madam Mim has lost the battle. Against all rules, she had turned herself into a dragon, but Merlin outsmarted her by becoming a germ and Mim caught the disease. To show her frustration, Eric animated a childlike temper tantrum. “Oh… you sneaky old scoundrel!” Mim pulls on her purple hair, and bounces up and down, which makes the ground tremble. At the end she resigns exhaustedly and leans back against a tree. Eric drew extreme, but funny expressions throughout the scene to show Mim’s fury. As her upper body moves backward, the legs come up for counterbalance, which results in a hilarious final pose.

© Disney

© Disney