In the 1995 documentary film Frank and Ollie, Frank Thomas voiced his frustration, while looking back over his long career:

I don’t think there was a day going by, where I didn’t think I was in the wrong profession, that I should get out of animation. I’d get so mad at something that was going on. Part of the time it was my own inability to draw what I wanted, which all of us had. I guess every artist has that kind of a problem.

A surprisingly candid statement about professional insecurity from one of the world’s top character animators. Frank Thomas might not have felt confident about his draftsmanship, but when it came to animated acting performances, he set the bar so high that very few artists ever came close to that level of excellence. Frank’s characters are so alive and move in such a natural manner, they seem detached from any animator’s conception, they live by themselves and make decisions on their own. Of course it is extremely difficult to achieve screen performances of such a caliber, and Frank Thomas worked harder than most at the studio, according to his colleague Ollie Johnston. While in the Disney training program, a junior animator said of Frank: “You just can’t please the guy, he is never satisfied.” Within the animation industry, Frank Thomas is known as the Laurence Olivier of animation.

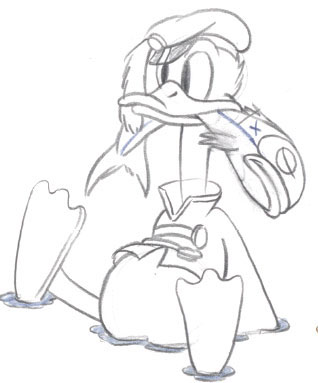

For the first two years at Disney from 1934 to 1936 Frank served as an in-betweener and as an assistant to the great Fred Moore. Fred had made significant breakthroughs in the art of animation, his use of squash and stretch helped Mickey Mouse to appear more believable and charming than ever before. Frank became a serious student of these new animation principles, and by 1936 he was given the chance to do a few scenes with Donald Duck for the short film Mickey’s Circus.

Captain Donald Duck feeds the circus seals … or does he?

© Disney

Another example of early Thomas animation is Pluto in Mickey’s Elephant, also from 1936.

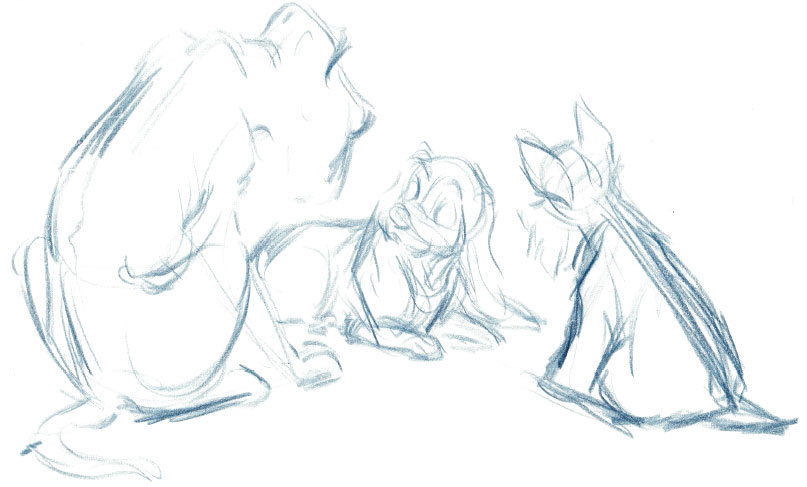

Pluto shows strong emotions, he is annoyed with the antics of a little elephant.

© Disney

Frank Thomas’ animation for Little Hiawatha caught the attention of Walt Disney himself.

© Disney

By now Frank Thomas was recognized as a new up-and-comer at the studio, who showed real talent. Walt Disney first took real notice of Frank’s outstanding animation when he saw scenes of a little kid encountering a bear cub up close for the 1937 short Little Hiawatha. This moment was beautifully staged as they meet in a nose-to-nose confrontation.

Frank still relied on his mentor Fred Moore for help as far as appealing draftsmanship, but the nuanced performance was all his own. Even this early on in Frank’s career, his characters move with real weight. The degree of squash and stretch is just right for cartoony characters like these.

And the acting choices reveal that Frank understood and felt their emotions deeply. His philosophy about animating could be summed up as: experience the character’s feeling first, then worry about the drawing aspect! In other words, it is the acting the audience will remember, the graphic presentation to a lesser degree.

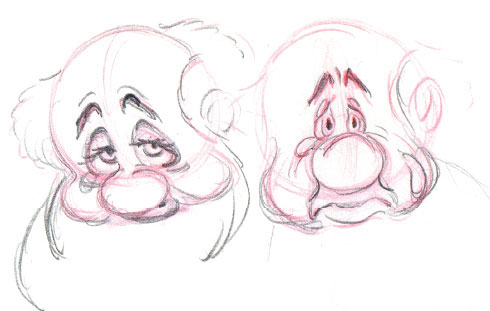

When it became time to cast animators for Disney’s first animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Frank Thomas was chosen to be a part of the dwarfs unit.

He animated the section where Snow White orders the dwarfs to wash up before dinner. They all reluctantly leave the house for the outdoor tub, each with their own characteristic walk. Another of Frank’s sequences proved to be a breakthrough for animated performances. After Snow White dies, the Seven Dwarfs gather around her body grieving the loss of their beloved princess. There are tears on the screen, and there were tears in the audience. For the first time, animated characters who experience sadness and sorrow deeply affected the viewers like never before.

Delicate facial expressions combined with subtle timing communicate believable emotions of sadness and loss.

© Disney

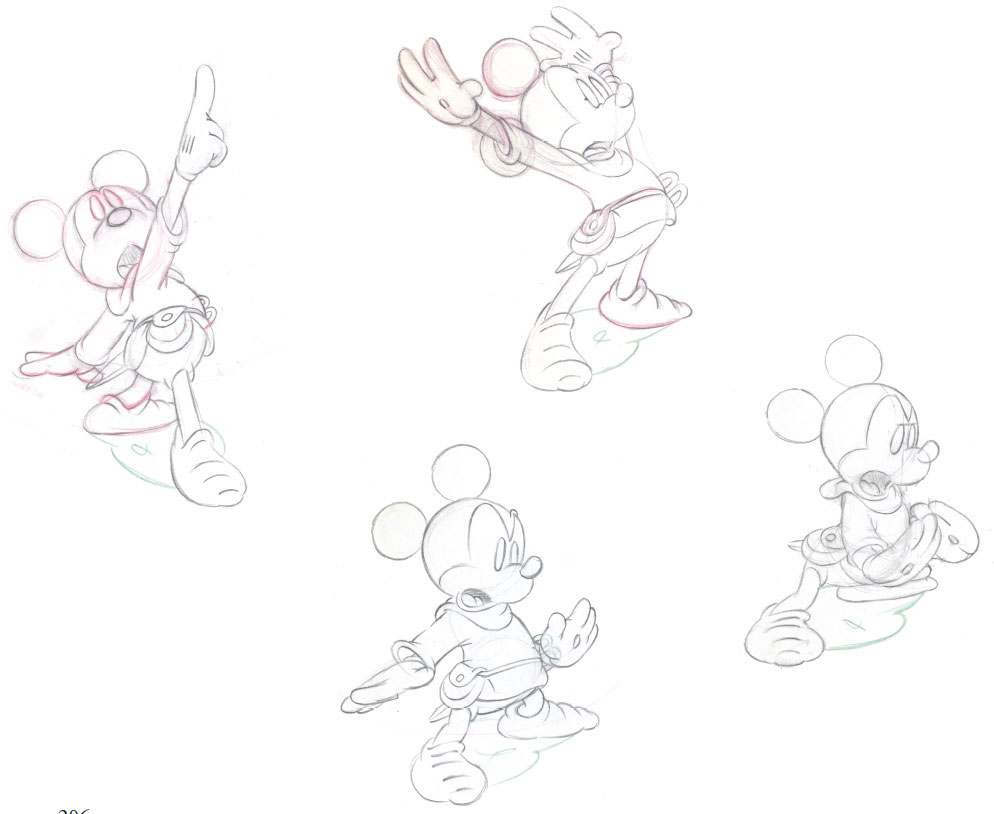

After finishing work on Snow White, Frank Thomas retuned to short films featuring Mickey Mouse. The Brave Little Tailor from 1938 includes a sequence that is often mistaken as having been animated by Fred Moore. Mickey is being presented to the King and Princess Minnie so he can tell his story about killing seven (giants) in one blow. He enthusiastically acts out the situation in which he found himself surrounded (by houseflies). “They were right on top of me, and then I let them have it,” he touts. The audience believes that Mickey is a giant killer, and a huge ovation follows.

Those scenes are arguably the finest as far as character animation goes for Mickey Mouse. There is no doubt that Fred Moore helped out with model drawings here and there, but the acting shows pure Thomas insight and analysis. The motion ranges from very broad to subtle as Mickey exaggerates his efforts in this confrontation. Every gesture and each step the character takes shows believable weight and perspective. The audience is watching living drawings perform.

Some of the finest character animation for Mickey Mouse can be found in The Brave Little Tailor.

© Disney

For the 1939 short film The Pointer, Frank animated Mickey facing off with a bear during a hunt. By now the famous Disney character had been given eyes with pupils, which allowed for even greater subtleties and emotional range. The comedic high point is Mickey’s attempt to explain his fame to the bear in an effort to be spared.

Walt Disney chose Frank Thomas to be part of the small team of animators that would supervise the animation of the character of Pinocchio. Frank’s insight into the inner feelings of the living puppet helped to bring him to life during Stromboli’s marionette performance. Pinocchio does his best to perform the song “I’ve Got No Strings,” despite his total lack of experience in show business. After an embarrassing fall onstage, the audience starts to laugh at him, but Pinocchio misinterprets their reaction and claps his hands enthusiastically. The whole sequence is full of rich character moments like this one, informing us of Pinocchio’s naïve good nature.

Mickey was given eyes with pupils, allowing for greater subtleties and emotional range.

© Disney

During production of the film, Frank gave a lecture to fellow animators on how to animate Pinocchio physically. He pointed out that the usual use of squash and stretch is to be avoided, because the character is made out of hard wood. When Pinocchio falls and hits the ground, the body mass must not be distorted during contact, instead he just bounces off the floor. This important principle helped to remind viewers that they are looking at a puppet.

Frank Thomas also animated a later sequence in the film, when Pinocchio, now with donkey ears, returns home to find Geppetto gone. He vows to Jiminy Cricket that he will find him, even after finding out that his father had been swallowed by a whale. This is an important turn in Pinocchio’s character development—he is starting to show a sense of compassion and responsibility.

The lack of squash and stretch when Pinocchio falls reminds audiences that he is made out of solid wood.

© Disney

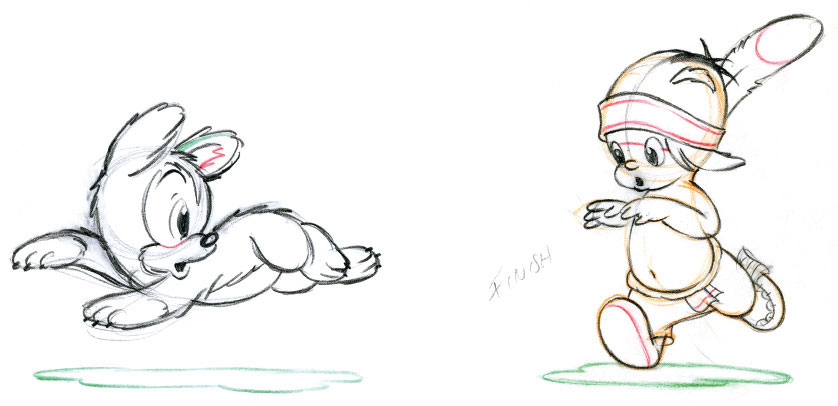

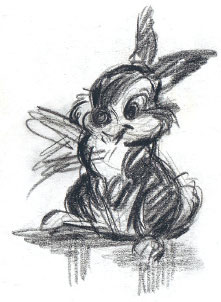

Very few artists were assigned to starting development and early animation for Bambi.

Frank Thomas’ talents were perfectly suited for a film whose character movements needed to be based on realism, to a degree never attempted before. These deer had to be drawn with real anatomy combined with tasteful caricature. Walt asked the animators to produce test footage; it seems like he was not entirely sure if he would get the results he was hoping for. Frank did rough animation of the scene involving Thumper as he is trying to teach Bambi how to say the word “bird.” In the process, Bambi mistakes a butterfly, who happens to fly by, for a bird, and he begins to chase it enthusiastically. After a few erratic moves, typical for a young faun, the butterfly lands gently on Bambi’s tail. The scene communicates poetry in motion. The superb animation has elegance and an almost dance-like choreography—Disney animation at a new artistic highpoint.

Perfectly staged and animated, this charming scene became an iconic image for the film.

© Disney

The very important sequence featuring Bambi and Thumper on ice was almost cut from the film as it was considered extraneous. Frank argued and fought to keep this section in the movie, knowing full well that this story material offered rich possibilities for personality animation. The contrast alone between the two characters couldn’t be greater. Thumper moves like a professional skater, while Bambi keeps falling over and over again, and Thumper’s instructions aren’t helpful at all. Frank animated the comedic antics of these two in a completely believable way. Whether the movement is subtle or broad, there is always weight, and therefore the characters look like real creatures. Today it is difficult to imagine the film without this highly entertaining sequence.

A rough layout pose shows Thumper’s confidence on the ice.

© Disney

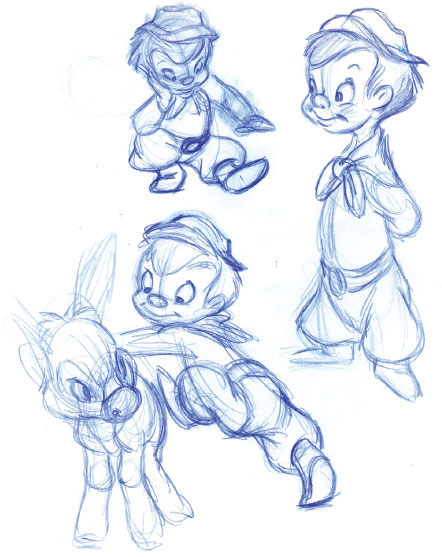

During the 1941 labor strike at The Walt Disney Studios Walt accepted an invitation by the US government to go on a goodwill tour of South America. Accompanied by a small group of artists, that trip also presented useful inspiration for the upcoming production of a series of short films based on Latin folklore and culture. Frank Thomas was a member of this traveling crew as the only animator. He helped design characters like the parrot José Carioca and the little Gauchito with his flying Burrito. Back in Burbank, Frank animated brilliant key sequences for the 1945 short film The Flying Gauchito. The main challenge was how to combine characteristics of a donkey with those of a bird for this fantasy creature.

Sketches for The Flying Gauchito.

© Disney

During WWII, Frank worked on a few propaganda short films like The Winged Scourge (1943), starring the Seven Dwarfs, and Education for Death (1943), which required character animation of Adolf Hitler.

After the war Walt Disney released The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad in 1949. The film presents two very different stories: one originates from English literature, the other is an American folktale. For the Mr. Toad section, which was based on the book The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame, Frank Thomas’ strong sense for character relationships came through in the sequence that introduced Toad to the audience. Rat and Mole are confronting Toad in an effort to talk some sense into their friend, who has been ignoring his responsibilities for Toad Hall. Instead he has chosen a lifestyle of carefree fun as he rides along out on the open road on his horse Cyril. The contrast between these personality duos is ideal for entertaining animation. Rat is sensible and serious, Mole is trying to be, while Toad and Cyril are utterly irresponsible without a care in the world. Rat’s body language is composed and businesslike, Toad’s acting shows broad, theatrical gestures that communicate a zest for life.

Frank explores range and flexibility within Toad’s body.

© Disney

The Ichabod Crane section offered Frank a sequence with an opportunity for all-out tour de force acting. Toward the end of the film, after attending Katrina’s party, Ichabod rides home through a dark forest. It is nighttime, and the Headless Horseman is very much on his mind thanks to Brom Bones’ impersonation of this legendary figure at the party. The sights and sounds of the forest bring out fear and eventually horror in Ichabod’s mind, but there is always the element of comedy in the way he reacts to the intimidating surroundings. He swallows nervously, covers his head with his lanky arms, and hangs on to his horse tightly.

This is not easy footage to animate—whatever Ichabod’s action might be has to be coordinated with the horse’s swaggering walk. Frank did this brilliantly, and it is astounding to find out that he animated this sequence at the super-fast rate of 40 to 50 feet per week. Incredible!

Frank animated this Ichabod Crane sequence at the rate of 40 to 50 feet per week.

© Disney

Walt Disney surprised Frank Thomas when he assigned him the villainous stepmother Lady Tremaine for the film Cinderella. “I had been known for cute, appealing characters. This was a very different kind of personality.” Frank knew about the challenge it would take to bring the stepmother to life. In order to be convincing, she had to be handled subtly and realistically. He got some help from actress Eleanor Audley, whose chilling voice performance inspired Frank a great deal. She also provided live-action reference, and Frank incorporated some of her nuanced acting into his animation. Frank later commented on the dangers that live-action footage could present. If photostats (printed frames of the filmed live performance) are being traced blindly, the animation will look soft and mushy. Actors have a tendency to slowly shift their weight from one leg to the other, something that rarely works in graphic motion. The animator needs to edit the live footage and find an essence within the acting. Usually poses need to be strengthened and the timing requires more contrast. Often whole sections are not being used at all because the animator found better ways for bringing the performance across.

A classic villain for the ages.

© Disney

Lady Tremaine’s subtle movements help to establish her truly evil personality.

© Disney

Cinderella’s stepmother is a perfect example of a villain who becomes much more evil and powerful by moving very little. Holding a certain pose or a specific expression allows the animator to show the character thinking. One of Lady Tremaine’s most powerful moments occurs early on in the film, when she confronts Cinderella while having breakfast in bed. She smilingly delivers an endless list of household chores; only occasionally does she change her expression to make fierce eye contact, reinforcing her impossible demands. A classic villain for the ages.

Frank Thomas animated a less realistic and much more comedic villainess for the next feature film Alice in Wonderland from 1951. The Queen of Hearts presented an interesting problem to the animator. How do you balance menace and comedy within her personality? Both were needed, and Frank struggled originally with these opposing qualities.

He eventually found a live version of this character while playing the piano with the Disney-Dixieland-Band Firehouse Five Plus Two. The group was performing on the island of Catalina when Frank spotted a heavyset lady in the audience. At times she was brash when talking to her husband, but she also had a dainty side to her when drinking a cup of tea. Frank all of a sudden had a person to base his new character on. Severe mood swings from one second to the next became a trademark for Frank’s brilliant animation. When the Queen gets angry, she loses all control and gestures wildly. During her composed moments, she usually shows a fake, smirky smile.

Frank originally struggled finding the balance between the menace and the comedy for the Queen of Hearts.

© Disney

Because the Queen of Hearts didn’t have much screen time, Frank was able to animate another character, the talking Doorknob. He interacts with Alice early on in the movie, when his door blocks the girl from following the White Rabbit. His animation is astounding, considering that this character is only a prop, an inanimate object. Frank gives him a full range of expressions, and on top of that he is able to maintain a keyhole for any mouth shape during his dialogue.

A full range of expressions for Alice in Wonderland’s talking Doorknob.

© Disney

There was more than one animator who wanted to draw Captain Hook, the villain in the 1953 film Peter Pan. Milt Kahl desperately lobbied for the assignment. But Walt Disney had Frank Thomas in mind, an animator with outstanding acting skills. Again there were two different character qualities that needed to work in unison. Some story artists had developed sequences showing Hook as a snobbish connoisseur of fine things, others showed him as a rough pirate.

Frank combined both approaches to create an entertaining villain, who could also be a real threat.

Through interaction with his sidekick Smee, who is also his confidant, we find out about Hook’s motives. He is driven by his goal to get rid of Peter Pan. Hans Conried voiced the character and acted out scenes for the animators. Frank used some of this reference carefully, starting with Hook’s introduction. He is studying a map trying to figure out Pan’s hiding place. The gestures are broad when he is frustrated; they become more subtle as certain ideas come to his mind.

The animation never feels like it is based on live-action reference, the final acting choices were made by the animator.

Hook is looking for Peter Pan’s hiding place.

© Disney

There are many brilliant sequences that give us insight into Hook’s personality. At one point he sweet-talks Tinker Bell into revealing Pan’s whereabouts. For a moment Hook becomes impatient and aggressive, but then catches himself to change his attitude again. “Continue, my dear!”

Frank was excellent at portraying complex mood swings, he often used irregular eye blinks to ease into the next attitude.

Frank excelled at showing Hook’s mood swings.

© Disney

For the film Lady and the Tramp, Frank Thomas animated important acting scenes with the leading dog characters. He developed Tramp along with Milt Kahl. Being a dog-owner for much of his life, Frank had already observed dog anatomy and behavior at home before he started on this assignment. In one of his memorable sequences, Tramp introduces himself to Lady, Jock, and Trusty, who are discussing the upcoming arrival of a human baby. Tramp interrupts the conversation and explains what a nuisance this newcomer to the family will be.

Frank plays off the contrast between the characters beautifully. Lady doesn’t quite know what to make of this street-smart intruder, while Jock and Trusty do their best to get this pesky dog off the property. Those scenes give us great insight into their personalities.

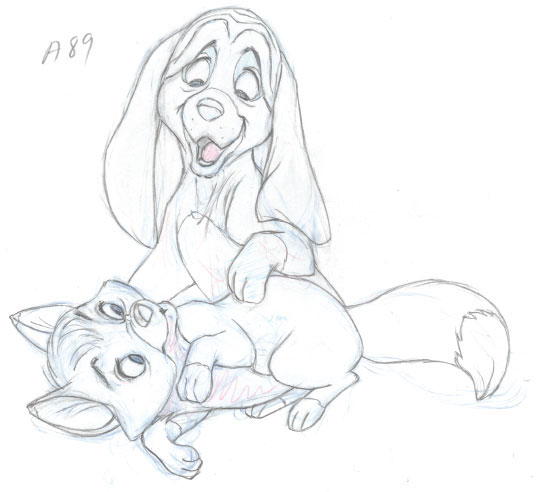

In this layout sketch Frank positions the dogs effectively as a group.

© Disney

It is not an overstatement to say that when Lady and Tramp share a spaghetti dinner in a romantic setting, movie history was made. Frank Thomas was the perfect animator to handle a sequence like this one. He turned what could have been an unappealing, messy situation into one of the greatest love scenes of all time. Beautiful draftsmanship, subtle animation, and insightful acting brought this moment to life in a way that no other animator could have done.

The look the two characters exchange toward the end of the dinner makes everybody believe that they have fallen in love. The scene became iconic not only for romance in film, but also for the power of Disney animation.

One of the most charming moments ever animated.

© Disney

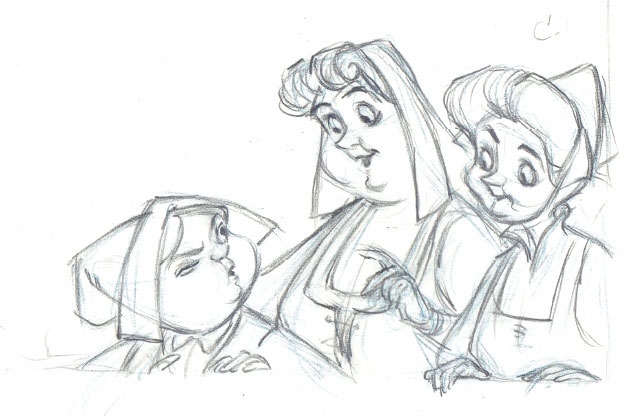

The three fairies have very different personalities.

© Disney

Frank teamed up with colleague Ollie Johnston to animate the three good fairies Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather for the film Sleeping Beauty. Both animators didn’t agree with Walt Disney’s original concept for these characters. He thought of them as sharing the same kind of personality, somewhat like Donald Duck’s nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie. Ollie and Frank argued that contrasting characteristics would make for a much more interesting trio. So Flora became the bossy leader, Fauna takes a little time to grasp a situation, and Merryweather is the most pugnacious one.

Perhaps because of their less realistic character design, the fairies are animated in a looser style than the rest of the cast. Their body shapes and facial features allowed for more expressive acting. Some live-action reference was used, but it is not evident in the final animated performances.

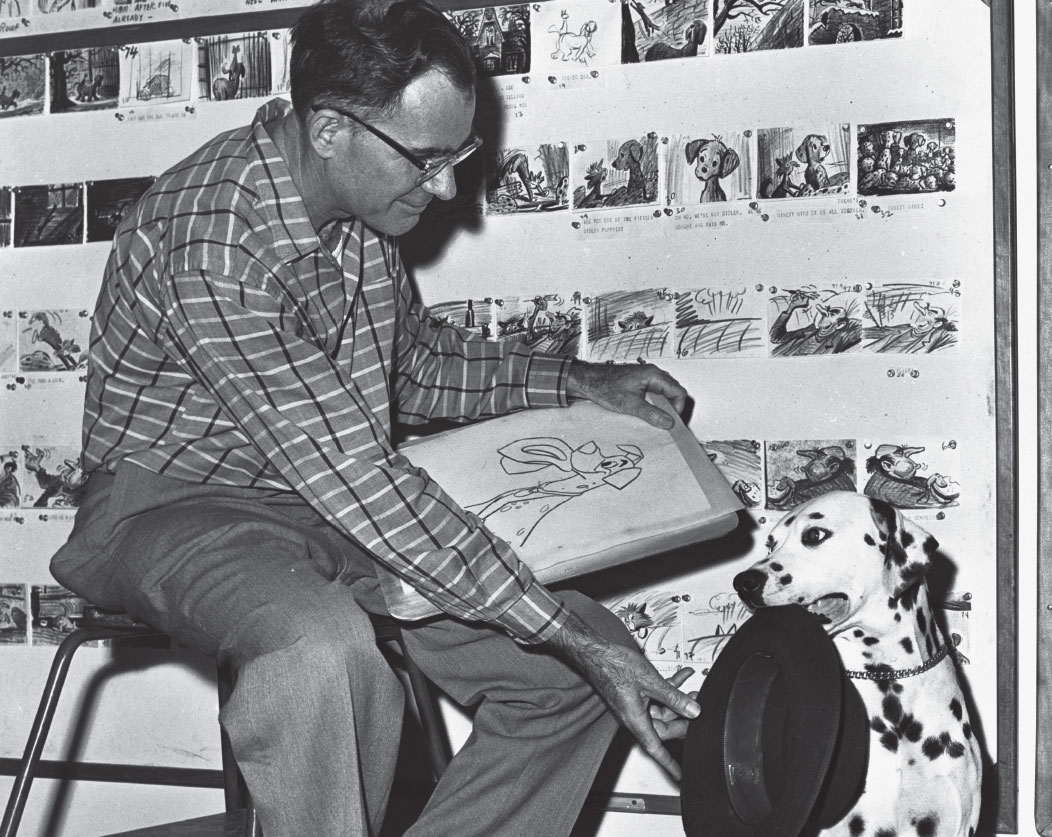

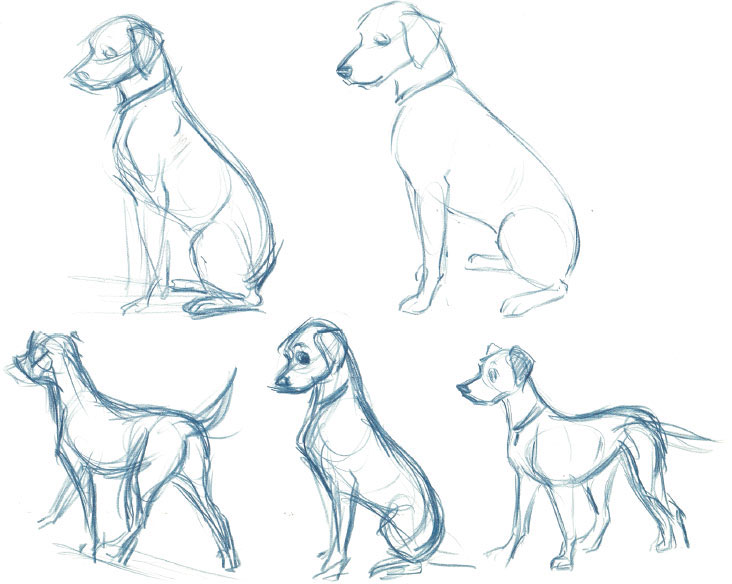

Frank helped supervise the animation of Pongo and Perdita in Disney’s One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Even though many animators were by now experienced in the motion of dogs, adult Dalmatians along with a few puppies were brought to the studio for study. Frank analyzed their specific proportions as well as bone and muscle structure.

Sketches showing the proportions and physical makeup of Dalmatians.

© Disney

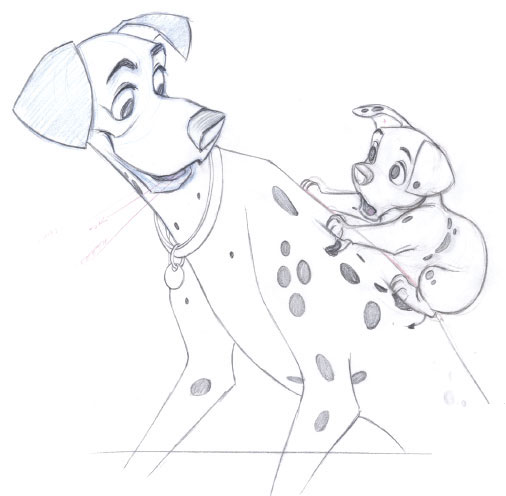

He animated charming scenes such as Pongo and Perdita’s decision to leave home to go on a search for their puppies. Later on they reunite with them in a barn in the company of cows.

One lovely scene stands out when one of the puppies, having positioned himself on top of his father, slides down his back. The way Pongo’s soft skin reacts to the puppy’s weight shows the believable contact between the two bodies.

Frank also animated the dogs experiencing some difficulties when they continue their journey on a frozen creek. Trying to walk on an icy surface is something Frank was familiar with since his animation of Bambi a couple of decades earlier.

The Sword in the Stone gave Frank Thomas the opportunity to work on a variety of characters.

A charming moment from One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

© Disney

He animated both Merlin and Madam Mim, as they prepare for the wizards’ duel. Mim sets the rules for the fight (she actually makes them up on the spur of the moment). Those scenes rank among Frank‘s best acting scenes ever. Mim is utterly convincing as she gestures theatrically. Merlin remains skeptical and adds a rule or two himself. As the two begin to change themselves into different animals in an attempt to outdo each other, we see Frank Thomas as an animator of action scenes. The chase is timed very sharply, and the individual transformations are inventive and entertaining.

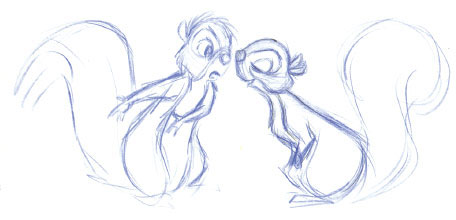

Another highlight in the film was also animated by Frank. At one point Merlin magically turns himself and young Wart into squirrels. He wants the boy to find out what life is like for a small creature of the forest. Things become complicated when a young girl squirrel shows her affection for Wart. Merlin finds a female admirer as well, and both of them do their best to escape these love-struck females. The whole sequence is about love, which can be passionate, silly, or disappointing. Frank later commented that the squirrel section was one of his favorite assignments at Disney.

Frank was excellent at animating dances, and he had the chance to show this skill in the 1964 film Mary Poppins, where four penguins were paired with actor Dick Van Dyke. Since the live-action footage was filmed first, Frank needed to be very careful in his animation to avoid collisions between a penguin and Dick Van Dyke. When the actor’s leg would swing sideways, the nearest penguin had to duck or jump over the leg to get out of the way. One might think that this could result in awkward choreography, but Frank actually took advantage of this challenge, and these little missteps added a wonderful and natural quality to the overall dance.

This sequence from The Sword in the Stone was one of Frank’s favorite Disney assignments.

© Disney

Three of the penguins who do their best to keep up with Dick Van Dyke.

© Disney

Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston were again paired to develop the intricate relationship between the man-cub Mowgli and Baloo the bear in The Jungle Book.

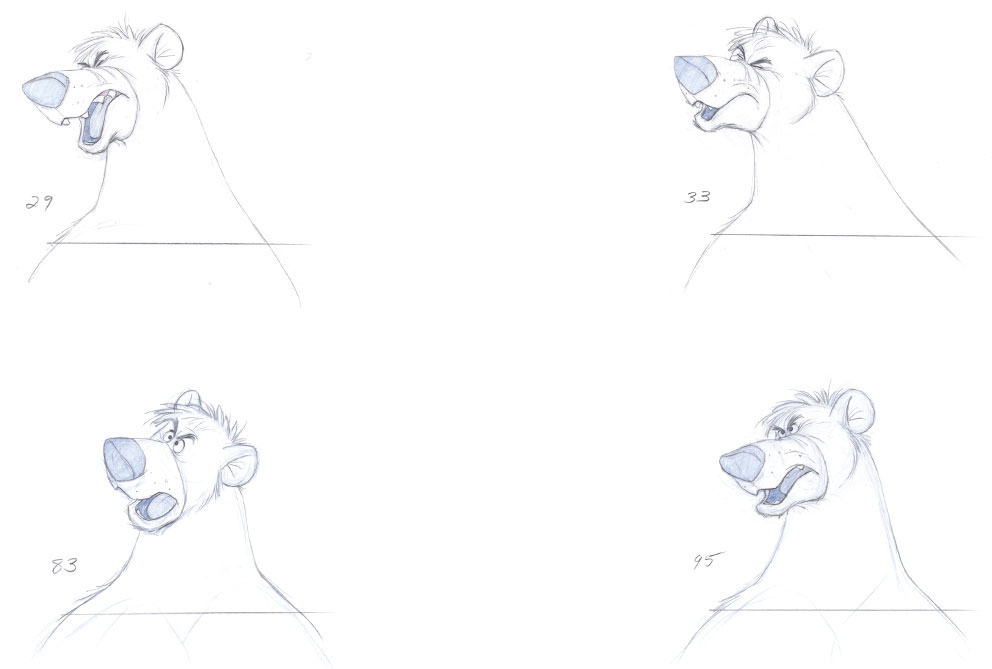

After these two characters meet, Baloo tries to teach Mowgli to behave like a bear. He challenges him to a boxing match. The boy gradually takes a liking to this carefree bear, and a beautiful friendship begins. Frank animated those poignant scenes, which rival any relationship from a live action film. Eventually Bagheera, the panther, catches up with them to question Baloo’s decision to take care of Mowgli. “And just how do you think he will survive?” he asks the bear. Baloo’s response is hilarious. He mocks Bagheera by repeating his question: “How do you think he will… what do you mean, how do you think?” He is obviously ticked off, and Frank found just the right attitude in his animation to communicate it.

Baloo, being upset at Bagheera, responds by mimicking him.

© Disney

The characters’ contrasting attitudes communicate clearly in this one sketch.

© Disney

Later in the film, Frank animated a deeply emotional scene, when Baloo is trying to tell Mowgli that he is taking him to the man village. The bear still doubts whether this was the right decision and he is trying to find the right words, anticipating Mowgli’s reaction to what he is about to announce. Only a master actor like Frank is capable of portraying a character with these complex, conflicting emotions.

Frank Thomas’ animation added a comedic touch to the sinister song “Trust In Me.” Kaa, the python, tries to hypnotize Mowgli with the intention of having him for dinner. Luckily the tiger Shere Khan interrupts just in time. Frank also animated important personality scenes with King Louie, the orangutan.

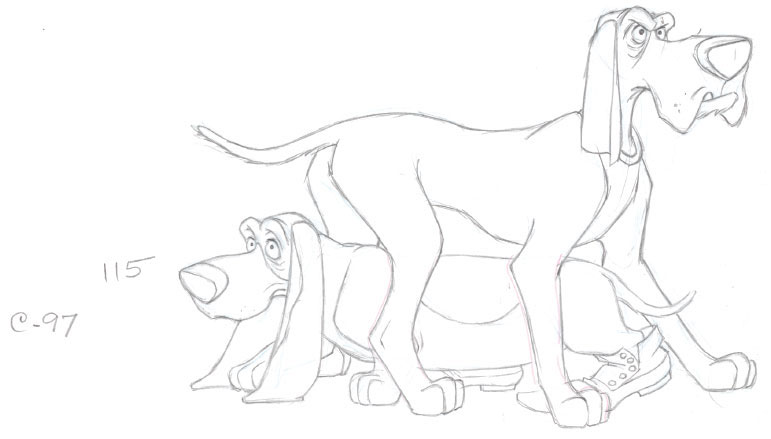

‘The next film, The Aristocats, offered Frank a variety of character assignments. He animated the romantic get together with alley cat Thomas O’Malley and the aristocratic Duchess. The sequence never reaches the originality and entertainment of Lady and the Tramp, but the animation is believable and fun to watch. Other characters who benefitted from the Thomas touch were the butler Edgar and the geese. Frank’s most memorable animation in the film is probably in the sequence that features the country dogs Napoleon and Lafayette as they try to settle for the night in their stolen motorcycle sidecar. They are constantly interrupted by Edgar, who attempts to retrieve incriminating evidence he had left at the crime scene. The two dogs act like an old couple, constantly bickering and finding fault with the other one.

The two canine stars from The Aristocats.

© Disney

Frank Thomas admitted that working on the movie Robin Hood was not a favorite assignment. There wasn’t a character he could fully develop, instead he helped out on various sequences that needed solid performances. When Robin Hood disguises himself as a stork to participate in the archery contest, Frank animated a character acting as someone else. Normally this would be an animator’s dream, but the story artists didn’t provide for the kind of situations that would translate into rich character animation. That being said, Frank’s performance of Robin as a stork is convincing to an audience. The fact that Prince John as well as the Sheriff of Nottingham at first buy into the masquerade seems believable.

A convincing disguise for Robin Hood.

© Disney

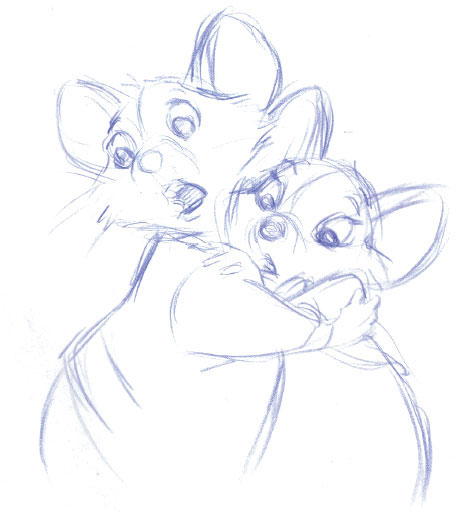

Reluctant agents Bernard and Bianca.

© Disney

The Rescuers is a film with a cast mostly made of small critters, and Frank had his hand in animating many of them, such as the lead couple Bernard and Bianca. Mice had often taken on comedic roles in Disney animation, but these two needed to have leading star qualities.

Their acting became less mouse-like and more human-like in order to carry the romantic as well as the adventure elements of the story in a believable way. Frank animated the charming sequence when Bianca chooses janitor Bernard to be her co-agent for the mission to find Penny, the orphan girl. He also drew the alligators Nero and Brutus, as they chase the mice while frantically playing the organ. Many scenes with the swamp animals, including Ellie Mae and Luke were also animated by Frank.

The Fox and the Hound (1981) was Frank Thomas’ final film. He worked on it for about one year, animating the pups Tod and Copper as they meet and play.

It is arguably the one sequence in the film that feels like vintage Disney. The motion is believable, and the acting is based on real children, having fun.

After retiring from animation, Frank and his friend Ollie Johnston started to write a series of important books on the techniques and philosophy of Disney animation. We are very lucky that these two men left their knowledge and wisdom in print. Animation is a complex art form that involves the study of many things, something that can be confusing and intimidating to any student of the medium. These books don’t offer any shortcuts or tricks, but they spell out what is involved in becoming a top animator: observing the world around you and interpreting human and animal nature through your characters.

The young Tod and Copper from The Fox and the Hound, Frank Thomas’ final film.

© Disney

Frank Thomas’ own animation is unique on many levels. From a technical point of view, it is interesting to note that when studying any one of Frank’s scenes, it is almost impossible to find definitive key drawings—the ones that frame the action and tell the story. To Frank, every drawing was important, they were all keys to him. He hardly ever moves into what is nowadays called a “golden pose.” Even within an important position, there is subtle movement to keep the animation alive. The motion never stops; perhaps that’s why Frank Thomas’ characters are living, breathing creations.

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad

1949

BROM BONES AND TILDA

CLEAN-UP OVER ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 7, Sc. 36

Frank Thomas had been known for his fine, subtle character acting, but here he shows that he is perfectly comfortable with broad action and comedy.

During the Thanksgiving Party, Brom Bones is in pursuit of Katrina Van Tassel, who is dancing with Ichabod Crane. Brom invites little Tilda to a dance, in hopes he can swap her with Katrina. Once a dancing item, however, Tilda vehemently resists any attempts to get separated from her handsome partner. Brom’s frustrated efforts to free himself lead to acrobatic as well as hilarious actions. As he tries to pull his hand from Tilda’s grip, his finger elongates for one frame. It’s a wonderful and surreal moment that signals that Brom Bones can’t win; Tilda is impossible to shake off. As the scene continues and the motion escalates, the girl manages to stay attached to Bones, having a great time along the way.

© Disney

The overlapping movement of the characters’ hair and clothing helps to make this frantic dance look fluid and believable.

© Disney

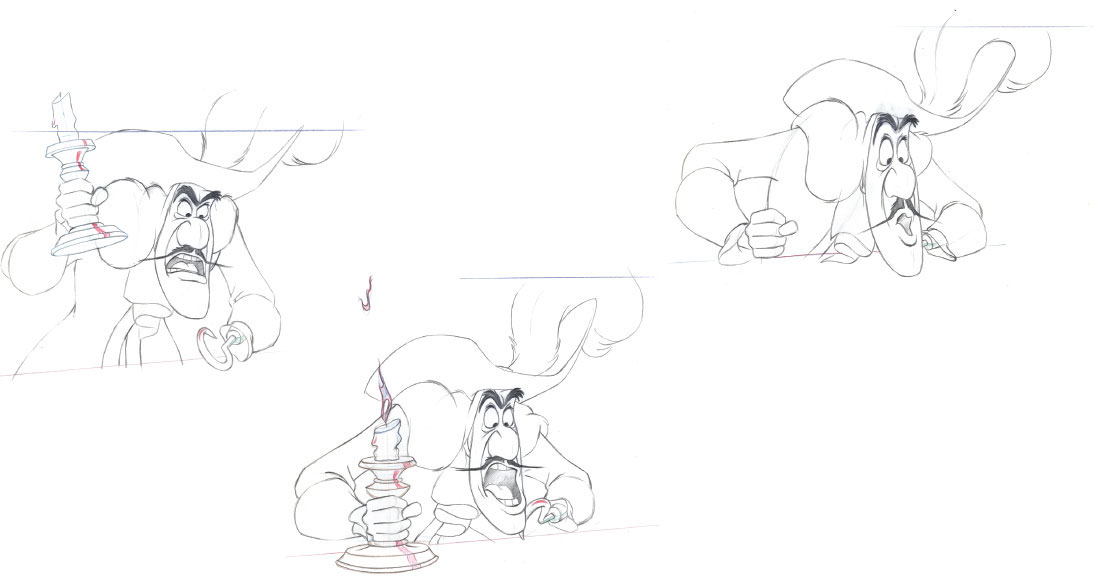

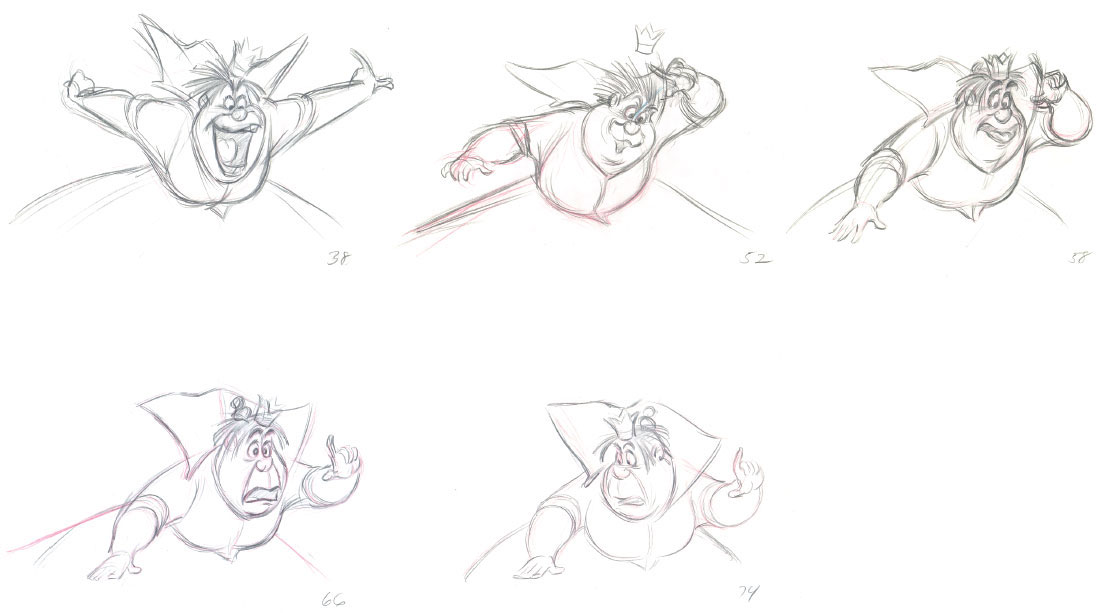

1951

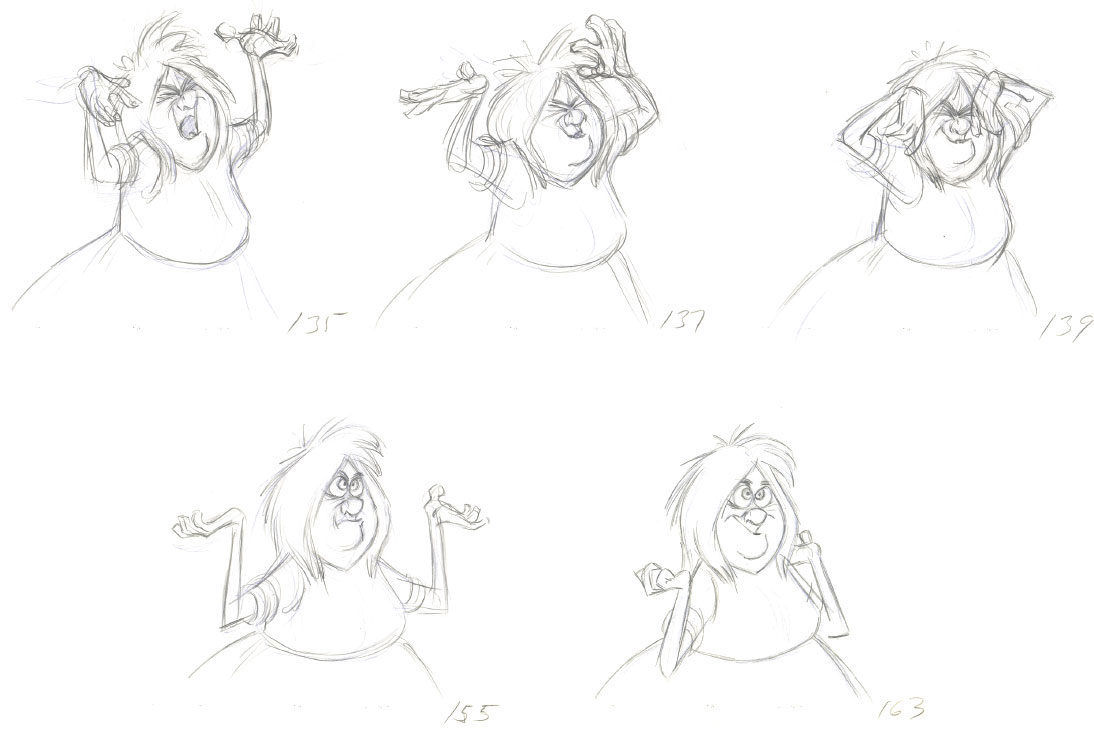

QUEEN OF HEARTS

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 11, Sc. 29

These few rough key drawings demonstrate the Queen’s volatile temperament and her abrupt mood swings. During the trial sequence, she startles Alice with her erratic reactions. At the start of the scene the Queen seems pleased: “Yes, my child…” Then suddenly her attitude changes and she bellows: “Off with her… [head]”.

She is interrupted by the little King who is pulling on her dress to get her attention in order to propose a different path for the trial.

Frank draws explosive, seemingly uncontrolled gestures before the Queen freezes in mid action. It takes her a moment to realize that she has been interrupted by somebody. The contrast in the scene’s timing with its fast and slow bits surprises not only Alice, but the audience as well. A most unpredictable character!

© Disney

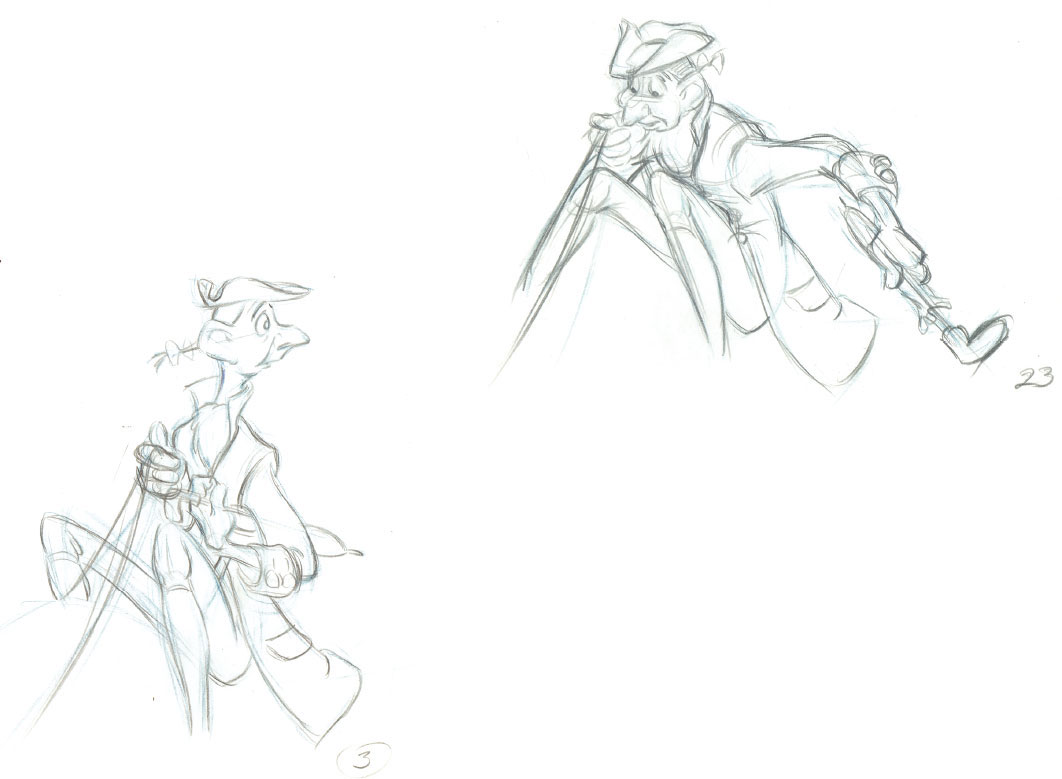

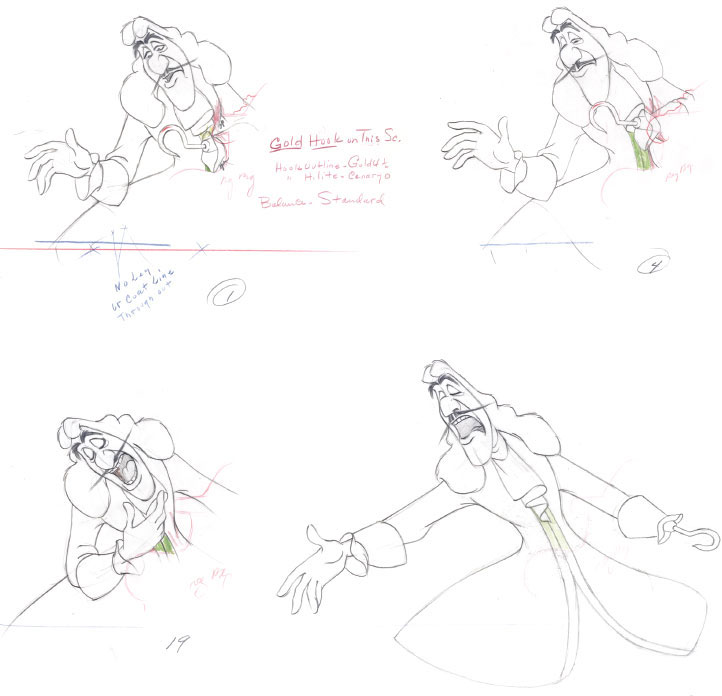

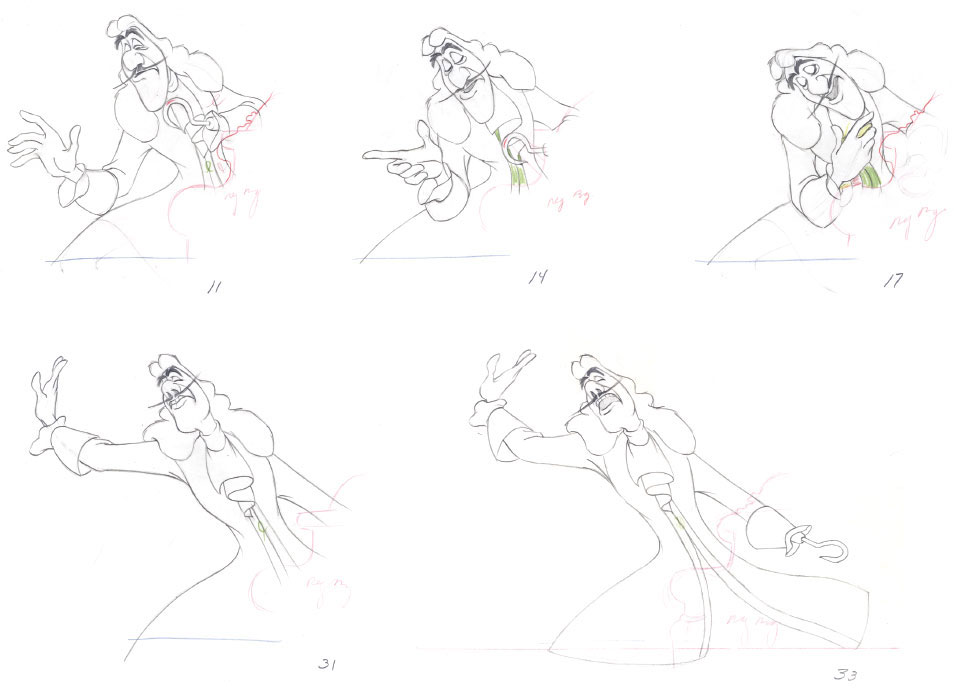

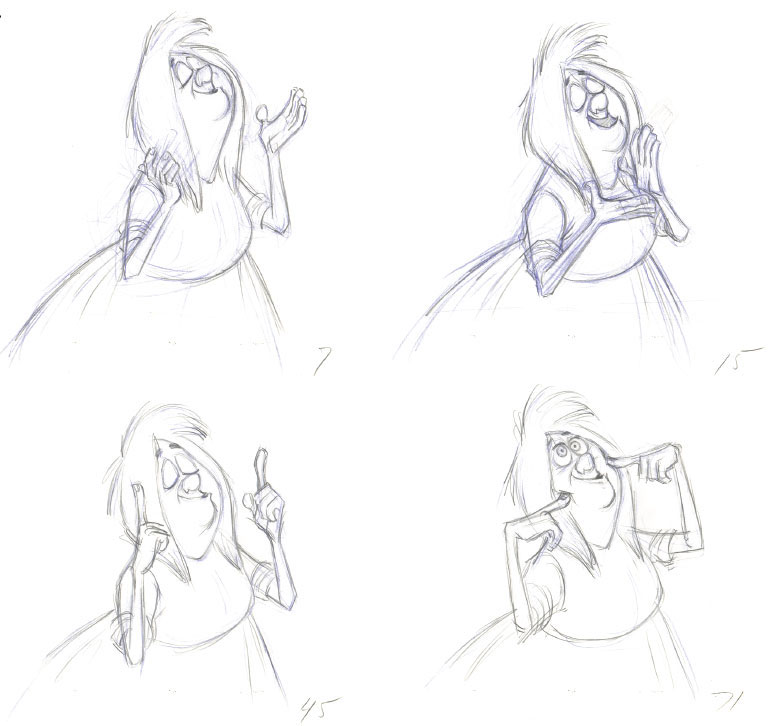

1953

CAPTAIN HOOK

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 11, Sc. 4

After capturing Tinker Bell, Captain Hook tries to gain the little pixie’s trust.

He admits defeat against Peter Pan. “Tomorrow I leave the island!” he promises in a grand theatrical, almost campy gesture. The scene is effectively staged from Tinker Bell’s point of view and requires Hook to be drawn in an up-shot. Particularly his last pose, which shows him rising up in perspective, puts the viewer at a low eye-level.

This is Hook, the actor, who has no intention of departing the next day.

Drawing from this angle could present a challenge for the animator. Foreshortening Hook’s elongated head is not an easy thing to do, but Frank knew that it was necessary to present the character in a high, superior position.

© Disney

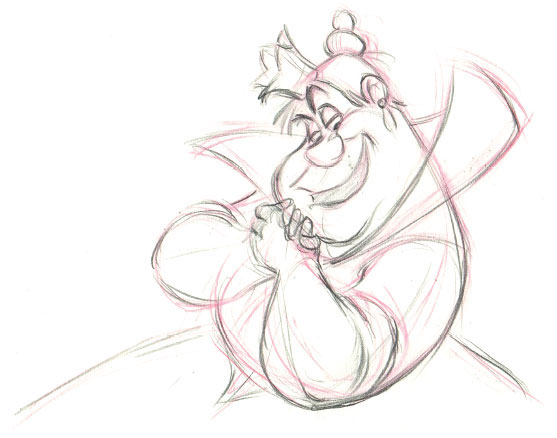

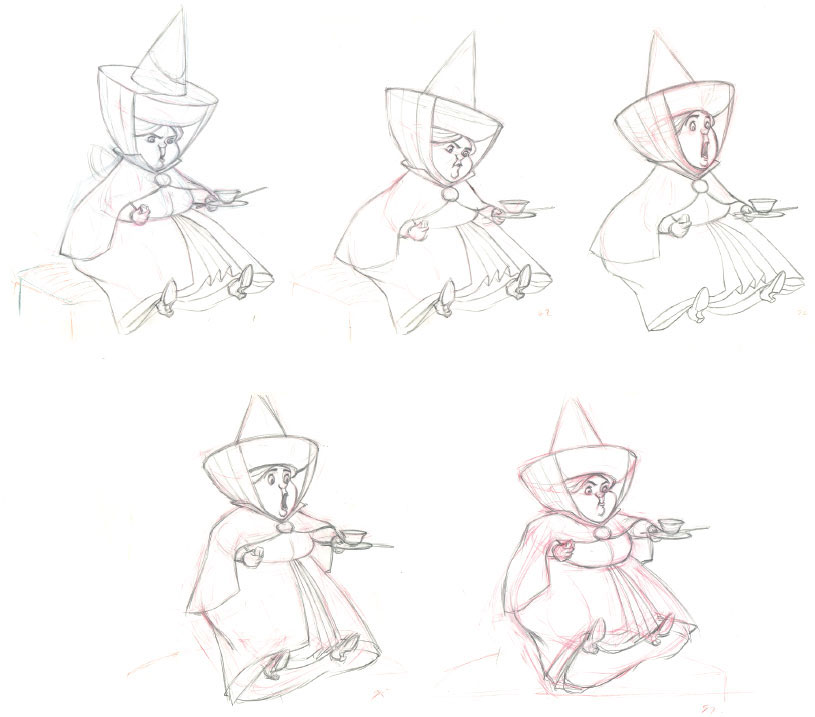

1959

MERRY WEATHER

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 7, Sc. 12

After Maleficent’s curse on the Princess Aurora, the three good fairies try to decide what to do next. Tea and cookies magically appear as the discussion about the evil witch continues. Merry-weather suddenly bursts: “I’d like to turn her into a fat ol’ hop toad!”

Frank takes full advantage of the scene’s acting opportunities. During the first part of the dialogue, Merryweather works herself into a squashed position with shoulders raised and head lowered. This pose serves as a strong anticipation for the jump that follows. For a second it seems Merryweather turns herself into a hop toad. The chubby fairy’s body stretches as it shoots upward. When completely airborne all her body parts become compressed before landing back on the chair. The fact that a drop of tea leaves her cup on the way down adds a nice touch.

© Disney

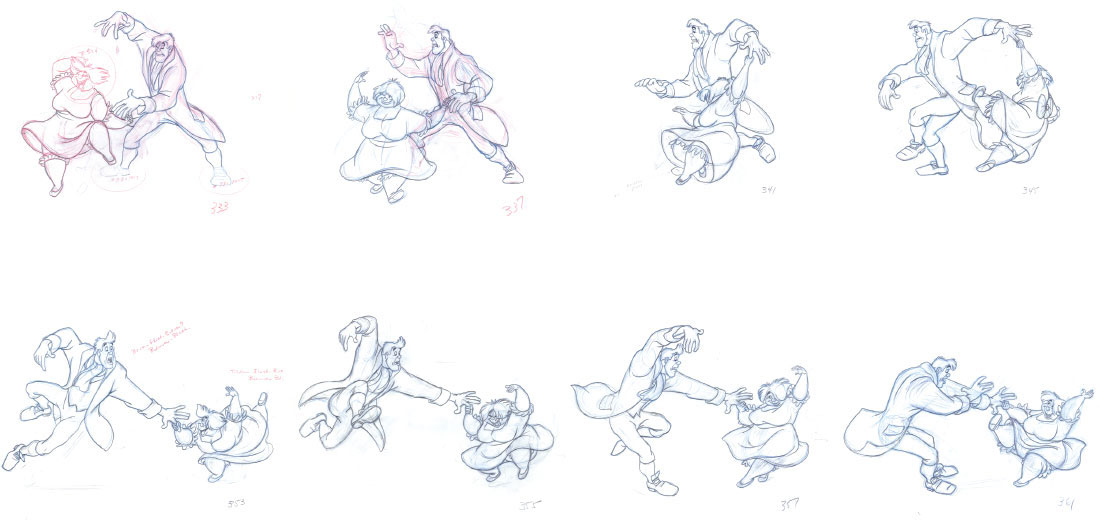

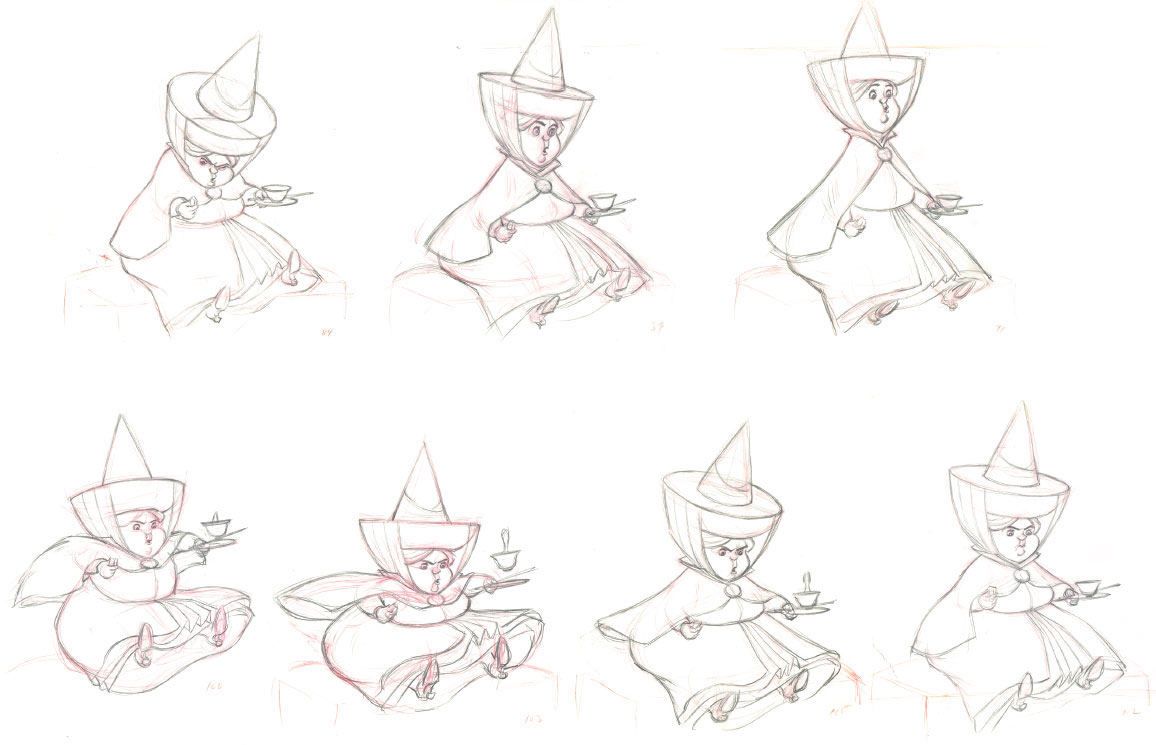

1963

MADAM MIM

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 10, Sc. 13.1

In this scene, Madam Mim continues to make up the rules about what and what not to turn into for the upcoming wizards duel with Merlin: “[Rule one, no mineral or vegetable]… only animal. Rule two, no make believe things like pink dragons and stuff. Now…”

Mim feels in charge here and is confident she will be the winner of this battle, knowing very well that she is going to cheat. Her theatrical poses display a sense of the fun she is having. When pink dragons come to mind, her hands gesture wildly to emphasize that those would be forbidden creatures to turn into.

Drawing-wise Frank, might have struggled a bit trying to get the head angles and hand positions just right, but as always he succeeds in orchestrating an interesting acting pattern that communicates the character’s true feelings. Mim’s emotion here is a sort of playful overconfidence.

© Disney

© Disney