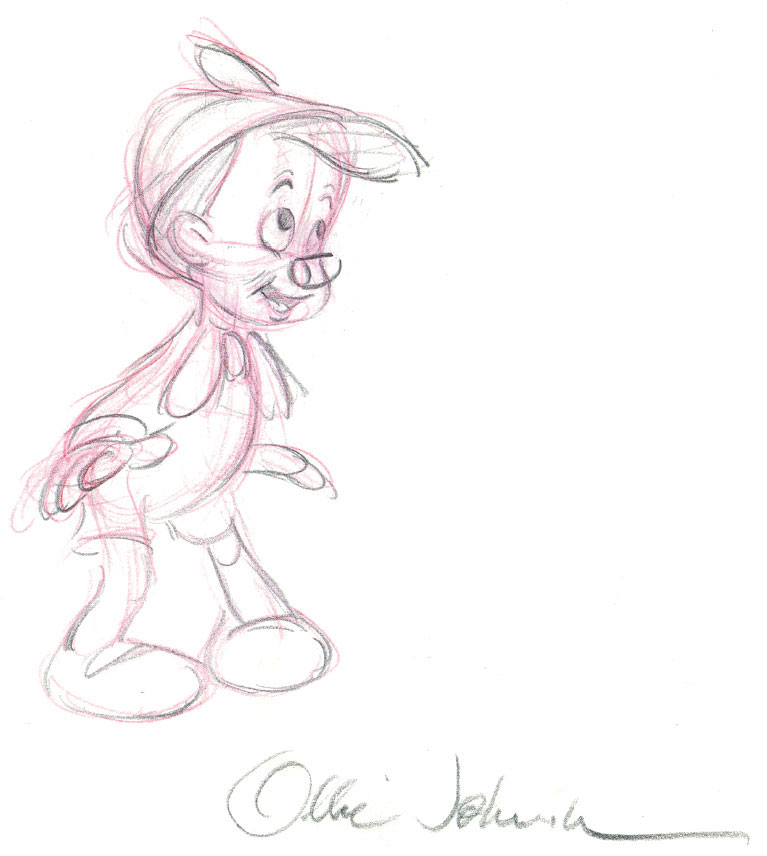

Ollie Johnston always felt that the characters he animated were living beings. “I never thought of them as just lines on paper—to me Pinocchio, Bambi, and Mickey really existed,” he stated once.

It is that conviction that led to a very personal approach toward animation, one where the animator analyzes and eventually identifies with the character’s emotions. Those feelings become the springboard for what the drawings will look like and how they will move on the screen.

Ollie never considered a particular design style that a film might call for to be a dominant factor in his animation. It was always the core of the character’s emotional state he was trying to get to more than anything. That insight was the most important thing that motivated him. “If the animator doesn’t understand what the character is feeling, the audience won’t either,” he said.

Most young animators tend to overlook this important aspect when trying to create believable animation.

The temptation to get started right away and draw before analyzing what is going on in the character’s mind is often too great. But those scenes will only show graphic motion, nicely executed perhaps, but void of any real emotional impact on viewers.

Applying Ollie’s philosophy can be a game-changer for many animators who are unsure of why their animation isn’t “coming off the screen” like classic Disney films do. It might sound simplistic, but when Ollie says: “Don’t animate drawings, animate feelings!” there is a profound meaning to those words. The idea is to learn how to draw so well that you don’t have to think about the quality of your draftsmanship as much, instead you need to focus on the characters’ performance. Animate from the inside out, understand and feel what they go through.

It is often helpful to search among one’s own family or circle of friends for inspiration. Do I have an uncle or a cousin who has a similar personality to the character I am animating? What would my uncle do in a situation like this one? Observing people’s behavior in real life is a tremendous asset to an animator’s work.

After Ollie Johnston arrived at Disney in 1935 he was put to work as an in-betweener, which was common for any newcomer. It was a way for the studio to find out about the young artist’s discipline, level of drawing, and work ethics. After in-betweening on several shorts, Ollie caught the eye of animator Fred Moore, who was looking for a new assistant. Production on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was about to begin, and Ollie ended up not only in-betweening Moore’s scenes, but also doing clean-up work on the dwarfs before eventually animating a few scenes himself. Ollie was in awe of his mentor’s talent; “Fred just couldn’t make a drawing that wasn’t appealing.” He also learned that part of what made a Moore scene look so alive was the fact that strong visual changes were taking place within his characters. The amount of body mass always remained the same but by treating it like a flexible water balloon, new life was added to otherwise stiff-looking animation.

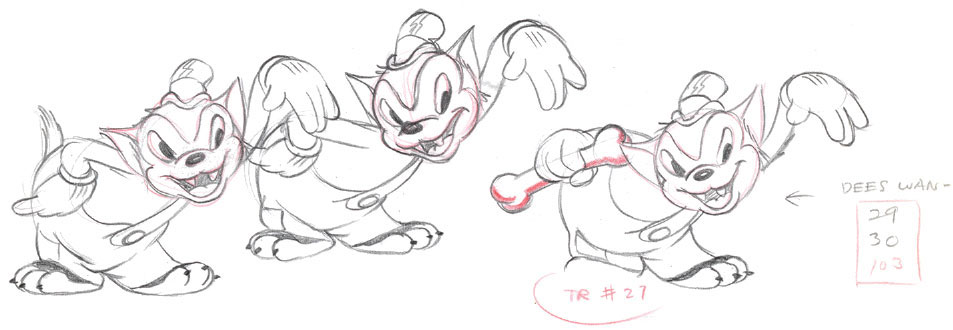

Ollie took full advantage of this principle when he was given a few scenes featuring various townspeople to animate for the 1939 Mickey short The Brave Little Tailor.

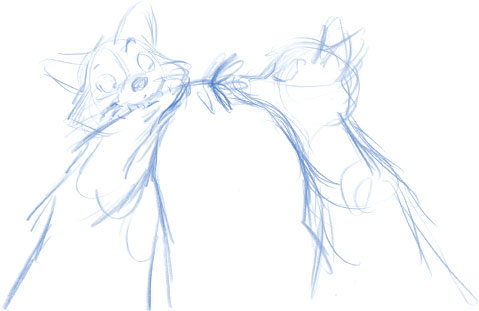

Early work on The Brave Little Tailor.

© Disney

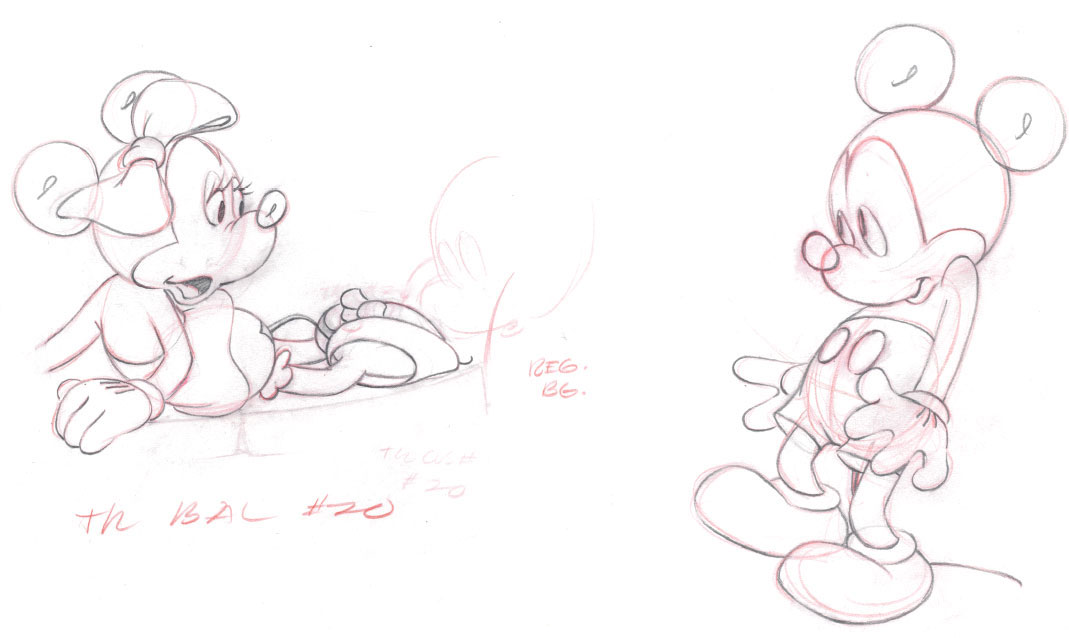

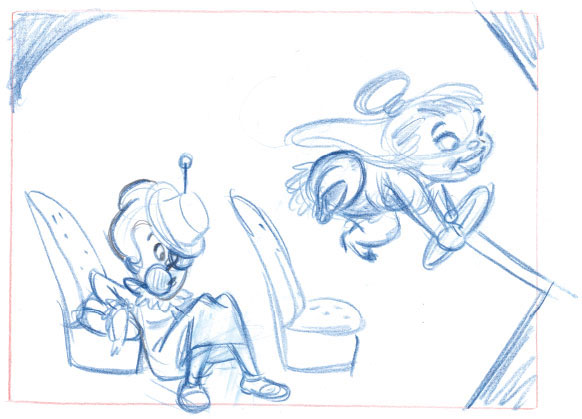

Walt Disney saw plenty of promise in Ollie’s work, and soon the young animator joined colleagues Frank Thomas and Milt Kahl to help supervise the animation of the character of Pinocchio. While some of the film’s story and design issues were being addressed, Ollie did animation for short films like The Pointer, The Practical Pig, and Mickey’s Surprise Party.

Fred Moore’s influence is evident in these early Johnston scenes.

Mickey is on the lookout for a bear.

© Disney

Three naughty wolves cause all kinds of trouble for the little pigs.

© Disney

Ollie’s versions of two Disney superstars.

© Disney

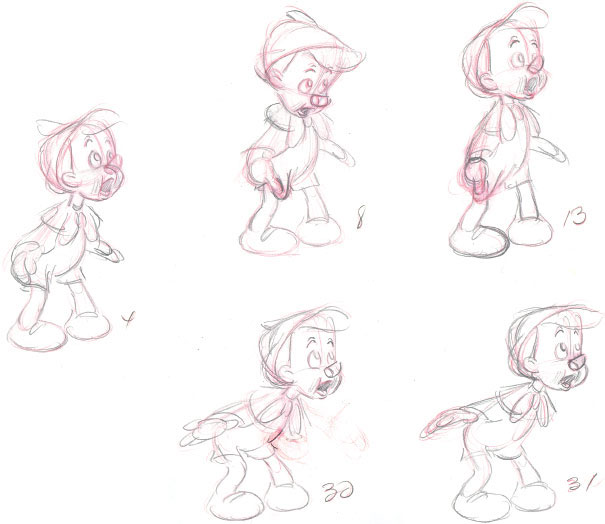

Pinocchio might be made out of wood, but he acts like a real kid.

© Disney

Ollie’s concept for Pinocchio’s personality was that of a well-meaning, naïve little boy:

“All he wanted to do is please his father Geppetto, but his lack of life experiences got him into trouble. After all, he had just been born.” The sequence in the film when Pinocchio comes to life was animated by Ollie, but Fred Moore still lent a hand when appeal and drawing needed to be strengthened.

Another section of the film that benefited from the Johnston touch was Pinocchio’s conversation with the Blue Fairy in Stromboli’s wagon. As Pinocchio tries to make excuses for not going to school, his nose starts to grow, the punishment for lying. The acting is subtle here; Pinocchio goes back and forth from being bewildered by his nose change to still trying to convince the Blue Fairy of his innocence. It is clear to the audience that he is very uncomfortable throughout the scene, because deep inside he knows that not telling the truth is probably a bad thing.

Pinocchio’s nose begins to grow.

© Disney

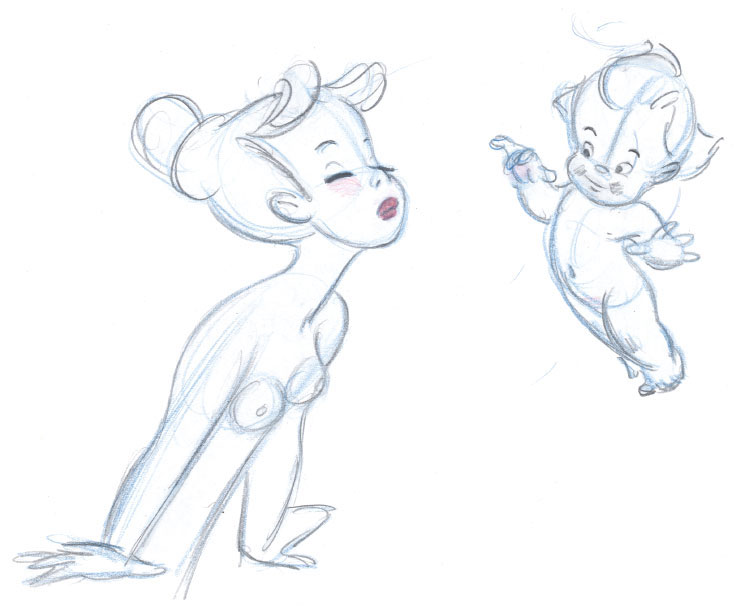

A makeup moment in the “Pastoral” sequence. Clean-up artists would later add floral covers to the topless centaurettes.

© Disney

While Ollie’s teammates Frank Thomas and Milt Kahl moved over to the Bambi unit, he was asked to help supervise the animation of cupids and centaurettes for the Pastoral sequence in Fantasia. These sexy fantasy creatures had been designed by Fred Moore, and Ollie brought them to life with feminine grace. He later recalled enjoying their “makeup” moments, when cupids apply lipstick and rouge to the girls’ faces. Originally animated topless, the clean-up artists later added floral covers in order to appease family audiences.

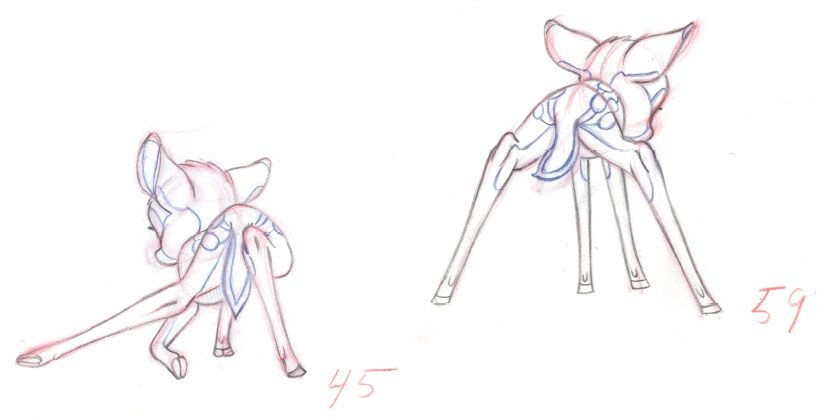

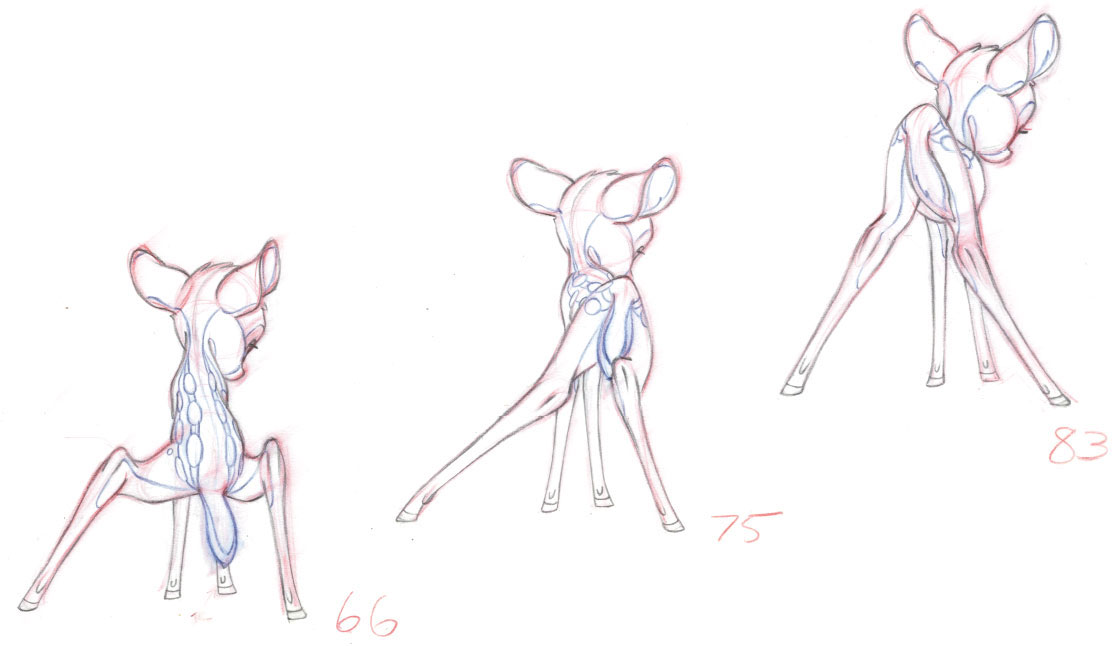

When story work for Bambi was finalized, Ollie and the other animators went to work and produced some of the most heartwarming and enchanting animated pieces of personality animation ever done. Particularly the motion of the deer characters has an almost poetic quality to it. Because these movements are often synchronized to music, the result looks elegant and balletic. One of those scenes was animated by Ollie. At the beginning of the movie, some time is spent showing how the young faun is still unsteady on his legs, and has difficulties balancing his steps. Bambi has just fallen to the ground yet again, and all the bunnies excitedly encourage him to stand up. With all this encouragement he is determined to show them that he is very much capable of walking. Bambi’s back is staged toward camera, we see him placing his weight on his left rear leg, then the right and left again, as his upper body rises up. There is definitely some effort that goes into getting up this way. He then proceeds to walk away from camera, followed by several bunnies. If there is such a thing as “poetry in motion” then this scene is it. Bambi gets into these beautiful poses on specific musical beats. Motion and music perfectly complement each other.

Bambi’s early attempt to walk was poetry in motion.

© Disney

© Disney

One of Ollie’s most charming scenes featuring Thumper, the rabbit, is when he suggests to Bambi that clover’s green leaves are really awful to eat. He knows his mother is watching, so he lowers his voice as he talks into Bambi’s ear. In this scene he is telling a secret to a friend in a typical childlike manner. Ollie enjoyed animating this type of sincere and entertaining character moment, unlike the upcoming assignments he would soon receive.

Telling Bambi a secret.

© Disney

The training and propaganda films produced during the war years were not much fun to work on, according to Ollie. But he did enjoy taking on the two leading ladies in the 1943 short Reason and Emotion. These characters live inside the head of a young woman, and they represent opposing sensibilities of her psyche. Their design is a far cry from the realism of Bambi, as these two are cartoony types, with potential for expressive animation. Ollie took full advantage of this assignment and brought the characters to life with a lot of guts. Reason is the conservative type, always proper and well-mannered. On the other hand, Emotion is impulsive and fun-loving, but irrational. The story offered rich situations for these two female opponents to disagree and fight with each other.

Ollie explores staging and contrasting attitudes for the female characters in Reason and Emotion.

© Disney

After the end of WWII, Disney got back to theatrical features with the 1946 musical film Make Mine Music. One of the short films included was based on Sergei Prokofiev’s composition Peter and the Wolf. For this section, the Disney artists drew character designs that are round and cartoony, yet the way they move displays a great deal of subtlety. You can see in Ollie’s animation of Peter and his Grandpa a careful balance of broad movement and delicate acting. When Peter is caught leaving the house in pursuit of the Wolf, Grandpa’s hand grabs the kid in a forceful move and carries him back inside. The forest is dangerous; kids have no business going on a hunt.

After Grandpa dozes off, Peter very warily approaches the old man and reclaims his toy gun from under his heavy arms. These movements are handled with believable posing and timing: a real kid trying to outsmart his grandfather.

Johnston finds the right staging for Peter and Grandpa in this layout sketch.

© Disney

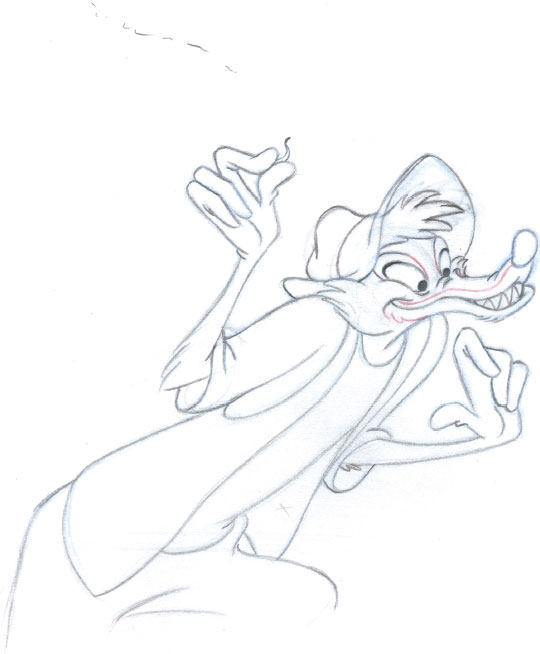

The film Song of the South gave Ollie plenty of opportunities to act out his characters in the broadest way possible. Dialogue scenes with Brer Bear, Brer Rabbit, and Brer Fox required razor-sharp timing. The key poses needed to read very clearly, because they were usually held for a brief moment, until a new thought process led the character to move into a different direction.

Ollie animated the argument between the fast-talking Fox and the massive Bear over who is going to enjoy Brer Rabbit for dinner.

Having been typecast in the past on adorable-type characters, Ollie proved on Song of the South that he was perfectly capable of zany, eccentric character animation.

Brer Fox proved Ollie could handle more eccentric animation.

© Disney

The short film Johnny Appleseed from the 1948 feature Melody Time turned out to be a much less enjoyable assignment than the exuberant characters in Song of the South. Ollie recollected years later that Johnny didn’t have a strong range of emotions: “He never got mad, never showed any deep feelings about anything.” Nevertheless Ollie did beautiful scenes with the character at the beginning of the short film, picking apples while singing a song. His movements are based on realistic actions, but there is a light cartoony touch as well. Whenever Johnny jumps, he stays up in the air for a few frames longer than a real person would, before landing on the ground. This kind of timing adds a bit of elegance as well as fantasy to the scene.

Ollie got the chance to show his talent for comedic timing in the Sleepy Hollow section of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad. The antagonist Brom Bones is furious with jealousy when Katrina starts to flirt with Ichabod. He waits outside her house, ready for a confrontation with the schoolmaster. As Ichabod exits, he saves himself by taking advantage of the double door situation.

Johnny stays in the air just a beat longer than is realistic, adding elegance to the scene.

© Disney

After producing several features that were comprised of individual short films, Disney returned to full-length feature story telling with Cinderella. The principal human characters like Cinderella, Lady Tremaine, and Prince Charming were handled very realistically, while the King and the Grand Duke turned out to be cartoony types. The stepsisters Drizella and Anastasia fall somewhere in-between. Ollie Johnston enjoyed developing these two comedic villains. They are extremely spoiled by their mother and take every opportunity to make Cinderella’s life a daily hell. Their appearance is more on the humorous side; Ollie refrained from drawing them as truly ugly, grotesque types, he preferred to play up their funny antics. One scene, however, was an exception. Toward the end of the film, Lady Tremaine (the stepmother) presents her two daughters to the Duke. After an awkward curtsey, Anastasia remarks: “Your grace.” In this close-up scene Ollie tried purposely to portray her as ugly as possible, so that the Duke would react in a repulsed manner. When Walt Disney saw the scene in pencil form, he told Ollie: “You might want to pull that expression back a little, she looks hideous.” The corrected scene still shows a very unattractive Anastasia.

Making Anastasia as ugly as possible.

© Disney

Not only does Ollie play up the comedy in Ichabod’s animation, but the much more realistic Brom Bones goes through a hysterical routine as well.

© Disney

In 1952 Disney released a charming short film called Susie, the Little Blue Coupe. The story was developed by Bill Peet and it deals with the ups and downs in the life of an automobile. It wasn’t the first time Disney turned modes of transportation into successful animated personalities—the train Casey Jr. in Dumbo and the plane Pedro in Saludos Amigos were living, breathing machines. But Susie was the first “thinking” automobile, a true challenge for any animator. Ollie Johnston found clever ways to humanize certain auto parts. The windshield became the eyes, the hood was turned into a nose, and the wheels assume functions of arms and legs. The audience completely identifies with this humanized vehicle, because of the character’s sincere emotions. Susie adores her new owner at the start of the film, but she is heartbroken at a later age, when being discarded onto a second-hand lot and eventually to a junkyard. The animator’s challenge was to inject human emotions into a machine and make it look entertaining. Ollie animated Susie’s body with surprising elasticity even though it is supposed to be made of metal. One of animation’s most lovable inanimate objects.

Susie was animation’s first “thinking” automobile.

© Disney

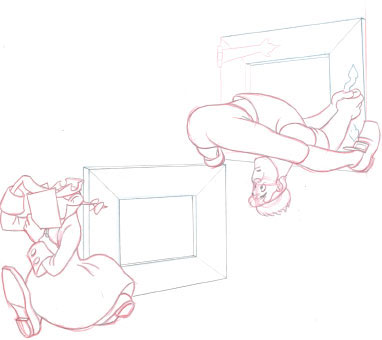

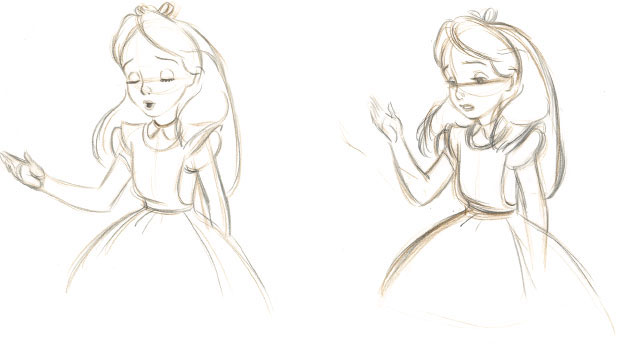

Working on the title character of the film Alice in Wonderland meant a shift for Ollie Johnston from broad animated types like Susie to a more finessed and realistic style of animation. Live-action reference was filmed to provide a basis for the animators’ work. Ollie found this method somewhat restrictive because the main acting choices were made by actress Kathryn Beaumont. But there were scenes that did call for the animator’s imagination. Ollie drew Alice meeting the talking doorknob, who encourages her to drink out of a particular bottle in order to change her size. Only then would she be able to pass through the tiny door. Early attempts fail and Alice becomes increasingly frustrated. Emotions like these on a realistic character needed to be carefully drawn and timed. Ollie pointed out years later that animating Alice wasn’t one of his favorite assignments, but that he learned a lot from working with live action. “It teaches you about subtlety,” he said.

Although Ollie found working with live-action reference challenging, he admitted that he learnt a lot from the experience.

© Disney

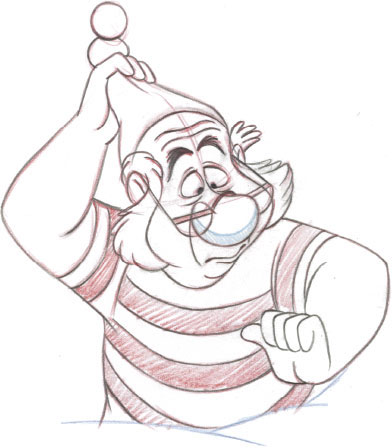

Smee is one of Ollie’s most entertaining creations.

© Disney

Ollie also animated the more caricatured King of Hearts, who turned out to be a much easier assignment. Broadly designed as a tiny character and in stark contrast to his mountainous wife, the Queen of Hearts, Ollie gave the King a unique way of running. His feet are not drawn at all, instead the lower end of his coat propels him to move forward. It is a nonsensical, fun type of motion.

But it was Ollie’s animation of Alice that impressed Walt Disney, so naturally he offered him the part of Wendy in the upcoming production of Peter Pan. Sensing Ollie’s frustration, Walt changed his mind and handed him Smee, Captain Hook’s pirate sidekick. This character assignment led to one of the funniest, appealing and most interesting cartoon creations ever created. Smee is basically a nice guy who feels the need to act mean only because his boss is the villainous Captain Hook. He even apologizes to Tinker Bell for capturing her so that Hook can interrogate the pixie. Smee often acts uneasy and is intimidated by the Captain. Ollie Johnston animated him with hilarious nervous gestures and attitudes. At one point in the film, Smee offers Hook a shave. Unbeknown to him, he ends up shaving the back side of a seagull instead.

Sheer disbelief and panic overcomes him when he find’s Hook’s head gone. “I never shaved him this close before!” His hands quiver as he feels through the wet towel searching for the missing scalp. He grabs the top of his hat and shakes it, not knowing what to do next. This is an extremely funny performance, full of inventive and surprising gestures.

Ollie ended up drawing most scenes with Smee, a character who ranks among his best animated efforts. Comic timing and brilliant acting choices make him stand out as a Disney sidekick who works for a villain but comes across as a likeable and entertaining type.

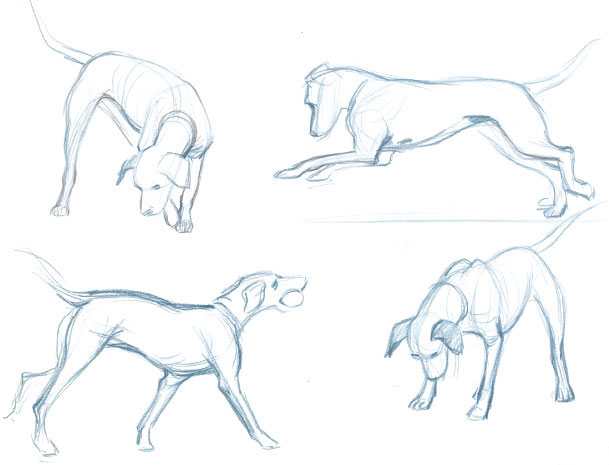

The dog characters in Lady and the Tramp required the kind of realistic approach in terms of their movements not seen since Bambi. These canines needed to walk and run with real weight. Lady and the Tramp is a sincere love story, making simple cartoony designs out of place.

Ollie did scenes with most of the dogs, including Tramp and Lady. One of his favorite dogs turned out to be Trusty, the old bloodhound. Ollie sympathized with this warm, grandfatherly type, who had lost his sense of smell. Trusty’s very loose skin gave the animators the opportunity to show these folds in overlapping actions, particularly in dialogue scenes. Ollie applied strong squash and stretch to Trusty’s face which not only adds age, but it is simply fun to watch.

Trusty, the old bloodhound who has lost his sense of smell.

© Disney

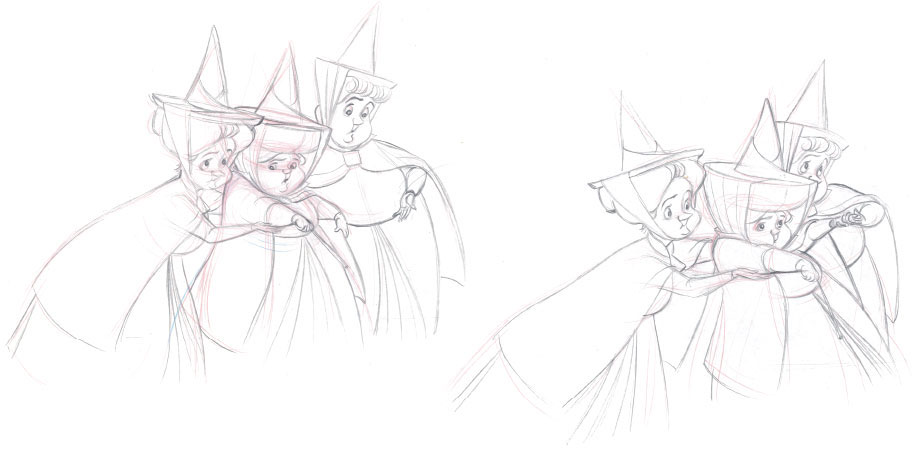

For the production of Sleeping Beauty, Walt assigned specific characters to certain animators. For the most part that animator would be responsible for that character only. An exception was the three fairies, who often were portrayed as one unit. Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather stand firm against Maleficent, help raise Aurora in the forest, and the happy ending is largely their work. But their personalities do differ from one another, which made them interesting and fun to work with. Ollie and his colleague Frank Thomas animated all of the fairies’ important acting scenes. With all three of them often appearing in the same scene together, staging and composition became an interesting challenge. Clear silhouettes in their poses were very important, so that the group image did not become confusing to an audience. Luckily the widescreen format provided ample space to place these three ladies in.

Flora and Fauna gently encourage Merryweather to give her gift.

© Disney

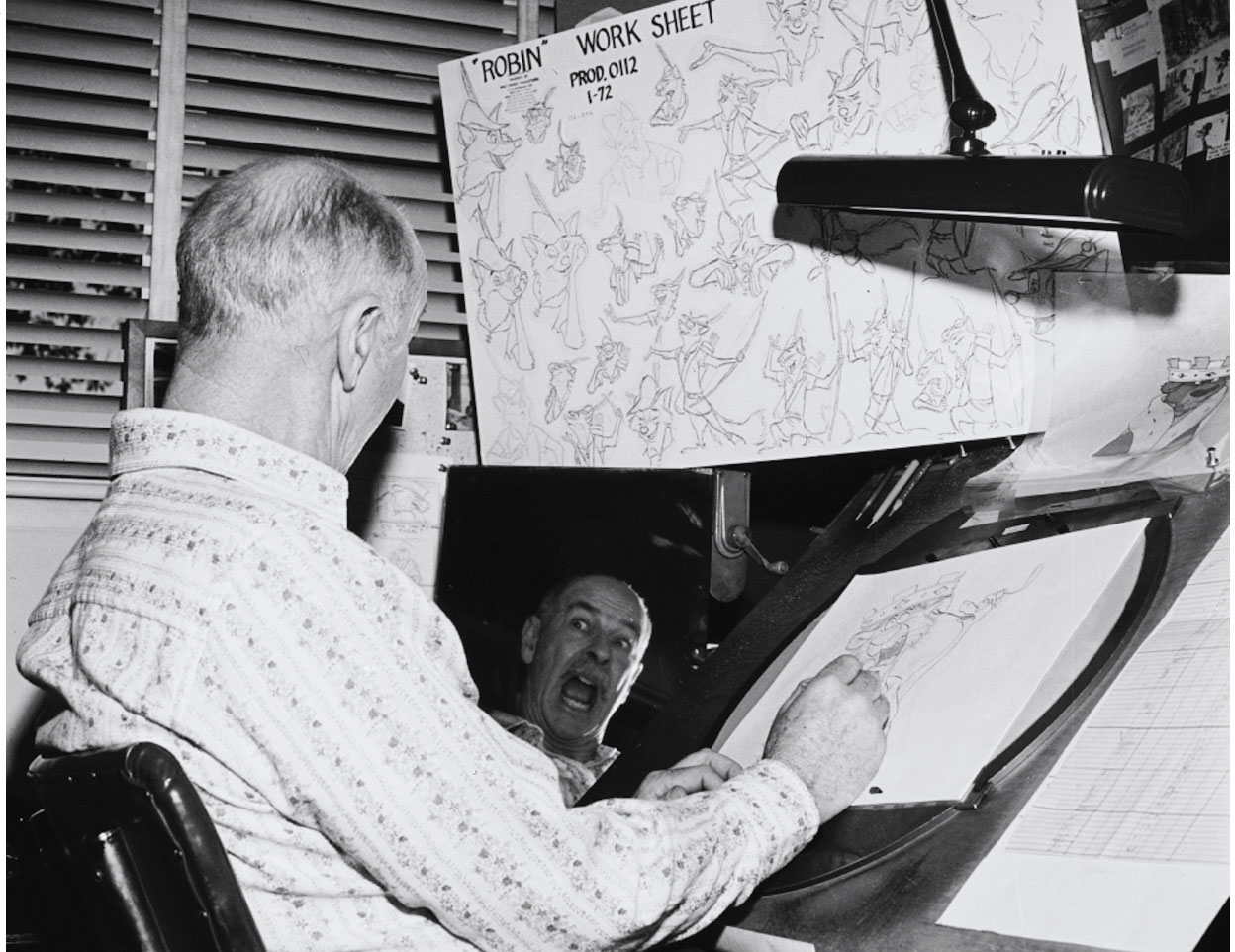

Ollie observes the anatomy and motion of real Dalmatians.

© Disney

The film One Hundred and One Dalmatians was groundbreaking for its sketchy look and modern art direction, but characters like Pongo and Perdita still needed to be animated the old-fashioned way. The routine of bringing Disney characters to life with drawings on sheets of paper had not changed at all. The animators started out by studying real Dalmatians before caricaturing them for animation.

A rough concept sketch for the moment when Pongo faces Cruella De Vil for the first time.

© Disney

At the beginning of the film, Ollie animated Pongo’s decision to pursue a young lady with her female Dalmatian, who had just passed by the house. He tricks his master Roger Radcliff into believing that it is time for a walk by changing the time on a clock. There is a strong sense of determination to catch up with the two ladies. Pongo pulls Roger along with all his might, until he finally spots them on a park bench.

A few key scenes involving the character of Nanny in One Hundred and One Dalmatians were also animated by Ollie. Visually she comes across as a possible relative of Sleeping Beauty’s three fairies.

Pongo straining to catch up with Anita and Perdita.

© Disney

Nanny is similar in style to Merryweather from Sleeping Beauty.

© Disney

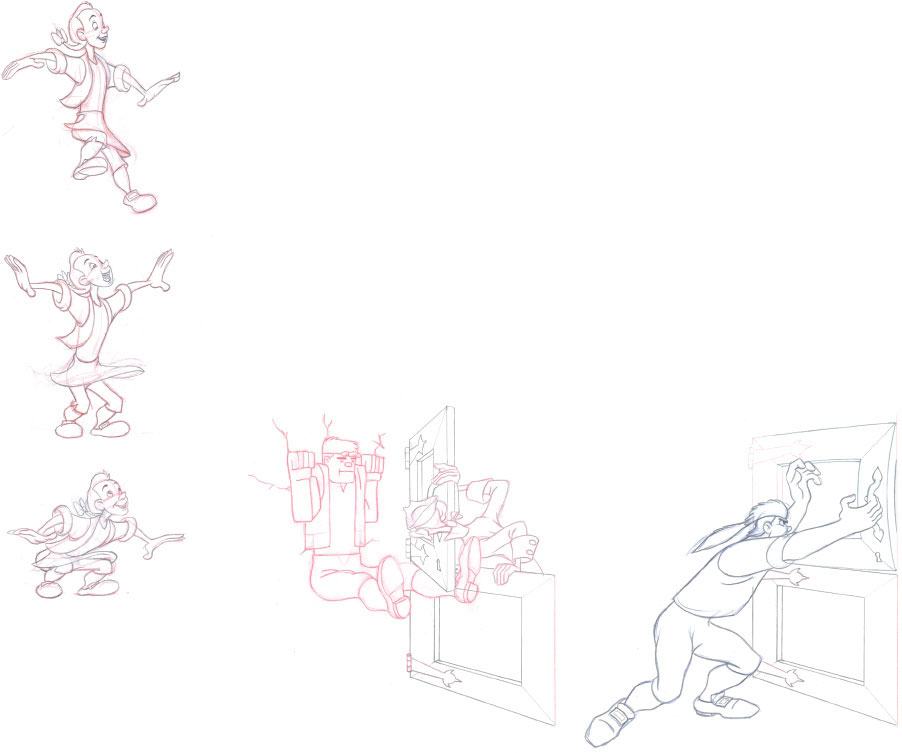

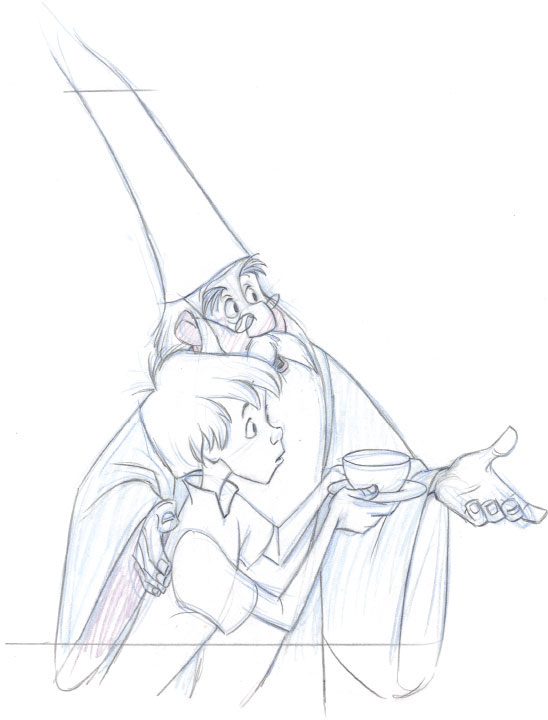

The Sword in the Stone continued the sketchy visual style that was introduced with One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Walt Disney had been critical of this “unfinished looking” approach to his animated films, but most animators enjoyed seeing their own pencil drawings move on the screen (instead of inked tracings). Ollie had a lot to do with developing the relationship of three of the main characters, Merlin, Wart, and Archimedes, the owl. They present an interesting dynamic. Merlin puts it upon himself to give young Wart a real education. Even though he does not succeed very well in this endeavor, the boy is in awe of the wizard. Archimedes is actually the smartest of them all and criticizes Merlin’s efforts frequently. Ollie animated most of the opening sequence of the film, when we first see Merlin as he is having trouble getting water out of a well. Eventually Wart appears as he literally falls through the roof of Merlin’s house, just in time for tea.

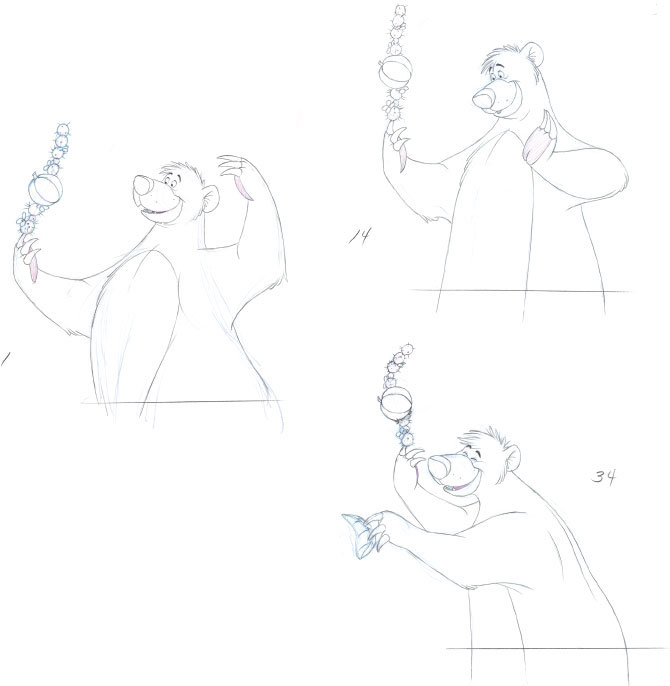

Even though Ollie enjoyed working on characters like Wart and Merlin, he thought that their relationship never reached the kind of depth you would feel with Mowgli and Baloo from The Jungle Book, the animated feature that followed The Sword in the Stone.

Wart and Merlin from The Sword in the Stone.

© Disney

A penguin waiter from Mary Poppins.

© Disney

In-between those two pictures, the animators were asked to animate characters that interacted with human actors. In the classic film Mary Poppins, Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke share the screen with cartoon farm animals, racehorses, and four cheerful penguins. Ollie Johnston animated these arctic birds as busy waiters, eager to serve Mary Poppins. The penguins’ movements as a group needed to be choreographed carefully, their hectic but enthusiastic actions would otherwise come off as confusing to watch.

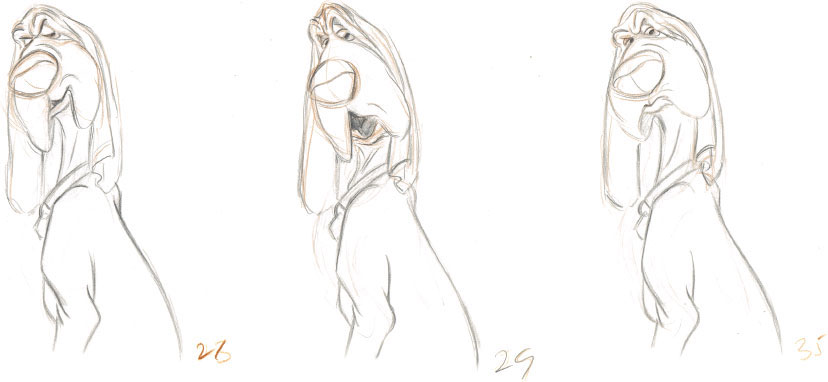

The Jungle Book is a unique Disney film, its story was kept extremely simple so that the characters would have plenty of time to interact with each other. Walt Disney knew that the entertainment needed to come from the animal characters’ performances, which left the animators with more responsibility than usual. Previous Disney films had been much more story-driven, but The Jungle Book relied completely on strong character animation. The studio at that time had a small but powerful animation unit that could deliver performances of the highest level. For the most part, animators were handed out complete sequences to animate, no matter how many characters were involved. That type of casting resulted in a situation where different animators worked on the same personalities. It gave them the chance to not only develop individual characters, but complex relationships as well.

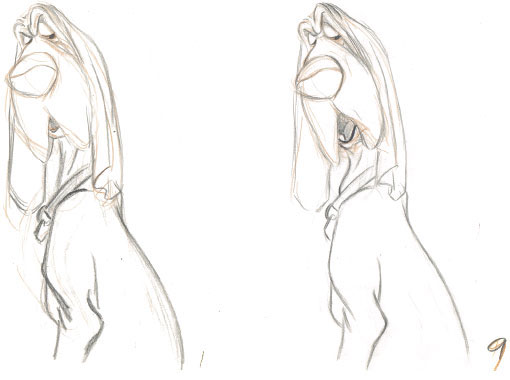

Ollie Johnston focused on Baloo and Mowgli, and he also animated scenes with Bagheera and the Girl at the end of the movie. Baloo’s introduction in the film is one of Ollie’s masterpieces. The bear’s carefree nature is immediately established by his on-screen singing and “dance walking.”

Those moves look completely natural and even improvised, yet a scene like this one requires a lot of analysis and careful planning from the animator. The character’s weight shifts constantly, arms and legs have separate unique moving patterns, and the action is synchronized to a musical beat. This complex kind of motion means that all drawings are done by the animator, there are no in-betweens. Every position is unique and important. Ollie recalled that Walt Disney himself had acted out Baloo’s steps one day in the hallway of the studio. That little performance by Ollie’s boss became the foundation for the personality of the bear.

FACING PAGE

Baloo’s dance walk was inspired by a demonstration given by Walk Disney.

© Disney

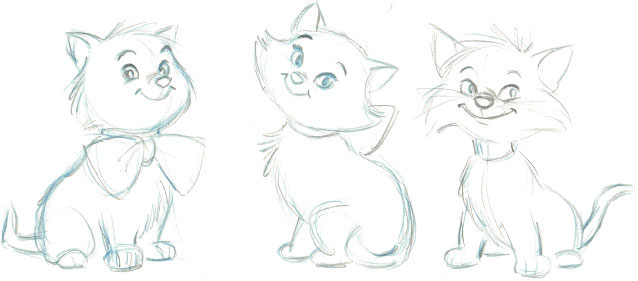

Ollie Johnston again developed some of the principal characters for the film The Aristocats. For most of his life, Ollie had been a dog-owner, and a lot of research for his canine animated characters was done right at home. But when he started to work on Duchess, the mother cat, and her three little ones, he proved that he had an affinity for felines as well. The kittens Marie, Toulouse, and Berlioz are effectively based on real children. As one would expect, the two brothers gang up on their sister often, and when things go wrong the familiar blaming game ensues. Their personalities come through during a music lesson and when Toulouse paints a portrait of Edgar, the butler. Their behavior and attitudes are sincere and childlike.

Although a dog-owner, The Aristocats proved that Ollie also had an affinity for felines.

© Disney

Ollie also animated scenes with Amelia and Abigail Gabble, a couple of English geese who giggle constantly. Watching them on the screen, many in the audience probably remember an aunt or two with similar character traits.

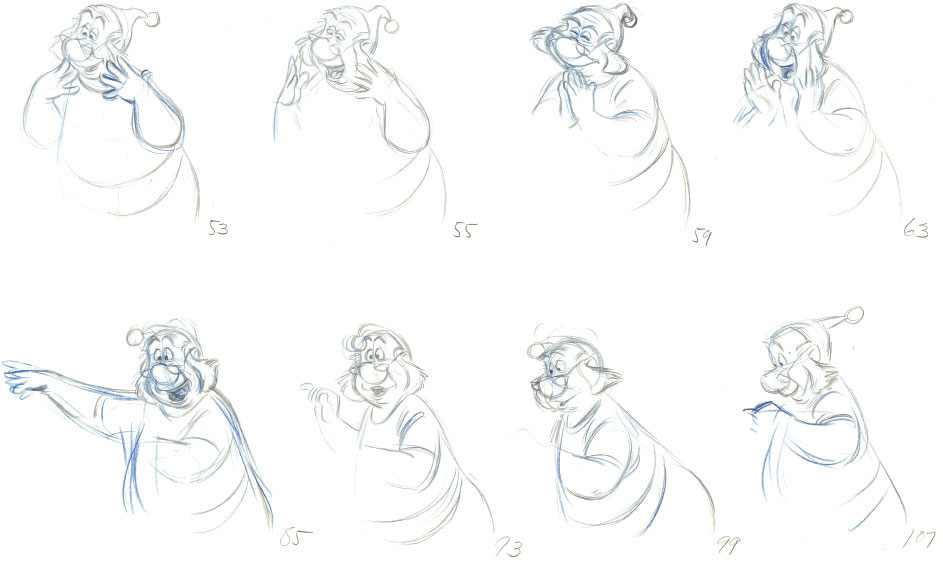

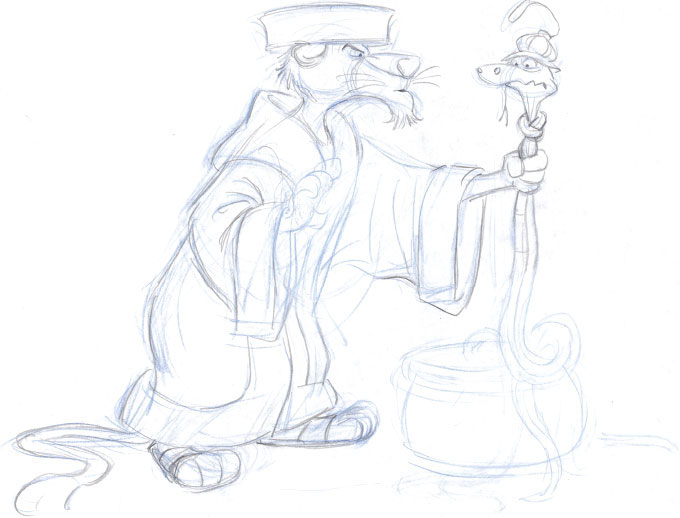

While these geese needed to move in a naturalistic way, Prince John from the film Robin Hood had to act much more human-like—after all, he was an anthropomorphic lion. His sidekick Sir Hiss might slither like a real snake, but he is also able to get into human-like poses by using his tail as a hand. Ollie saw the potential for rich personality material, and he created tour de force performances with these two comedic villains. Their facial expressions are based on the actors who provided their voices. Peter Ustinov is Prince John, a cowardly lion, and Terry-Thomas is Sir Hiss, a sniveling snake. The film’s story might not come up to classic Disney standards, but as far as character relationships go, this is one of the most entertaining. Prince John seeks constant confirmation for being a good monarch and when Sir Hiss doesn’t comply, physical punishment follows. Nevertheless, Hiss is committed to pleasing his boss, which makes him a partner in crime. It was important that Ollie handled both characters. If another animator had drawn Sir Hiss, for example, their interactions would not have been as seamless. When Prince John acted aggressively, Ollie knew immediately how the snake would have to react.

Ollie captures the uneasy relationship between two comic villains.

© Disney

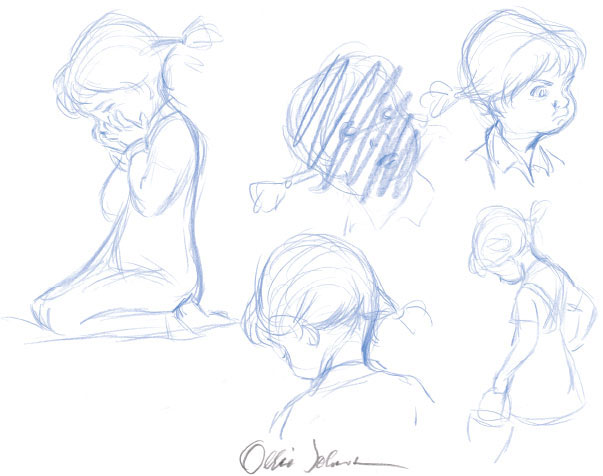

The orphan Penny from The Rescuers.

© Disney

For the film The Rescuers, Ollie was assigned to several characters. He supervised the animation of the orphan girl Penny and Rufus, the old cat. He also developed the personality of Orville, the albatross who runs his own airline. Several important acting scenes featuring the mice Bernard and Bianca were also drawn by Ollie. This is very diverse group of characters, from sentimental and comic to leading types. It is fair to say that Ollie carried a large part of this picture with quality animation, but also quantity. His most important contribution was arguably developing Penny into a character the audience would feel for. This is a girl who is sad for most of the film, not necessarily an appealing attitude to watch for long. But the way Ollie expressed her inner feelings to Rufus reveals that she still holds a glimmer of hope to be adopted one day, and that makes her sympathetic and appealing.

Ollie’s farewell animation assignment was for the 1981 film The Fox and the Hound. At that time Disney’s veteran master animators had taken on a second role as teachers to a new generation of animators. Ollie lectured and gave advice to several newcomers to the studio, including Tim Burton and Glen Keane. But he still found the time to animate one sequence. Tod, the fox meets Vixey in the forest, and his attempts to impress her result in some awkward, but funny moments.

Both Ollie and his colleague Frank Thomas stated that they did not feel challenged working on The Fox and the Hound. The story material and the character concepts were too familiar and reminded them of previous films they had worked on. It was time to put down the pencil and pursue new interests. For the next few years Ollie and Frank wrote a number of important books on character animation and Disney philosophy in general.

Looking over some of Ollie Johnston’s drawings, there is a lot to admire. A special appeal can be seen in all of them, whether it is a hero or a villain we are looking at. Ollie never forgot what he had learned from his mentor Fred Moore, that charm is an important ingredient in depicting a character. Without it, the audience might lose interest.

It is also interesting to observe Ollie’s light touch with pencil and paper. It seems like he never got frustrated during the animation process. Just a few careful construction lines with delicate pencil strokes on top. This meant that he spent little time on one given drawing, he quickly moved on to the next ones. Ollie Johnston was not only one of Disney’s best animators, on many film productions he was also the fastest. What an astounding talent!

Ollie’s final animation assignment was The Fox and the Hound.

© Disney

1940

PINOCCHIO

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 4.9, Sc. 21

These beautiful drawings define Pinocchio’s emotions sensitively and with great insight. The Blue Fairy has reappeared and is wondering why he didn’t go to school.

Being locked up in a cage Pinocchio feels embarrassed to face the Fairy. “I was going to school… ’til I met somebody.” During the first part of his statement he looks concerned; he doesn’t quite know what to tell her. But, the fact that he met somebody is actually the truth, and his expression changes to a smile. For a second he is proud of himself and his explanation, so far so good. But moments later he changes his angle and reports that he ran into two big monsters with big green eyes. Perhaps a little lie will get him out of this interrogation.

Ollie found the perfect uneasy gesture to visualize the dialogue. Pinocchio uses a finger to twirl one side of his shorts. Ollie emphasizes the word met, as Pinocchio leans forward showing a hint of confidence in what he just said.

© Disney

© Disney

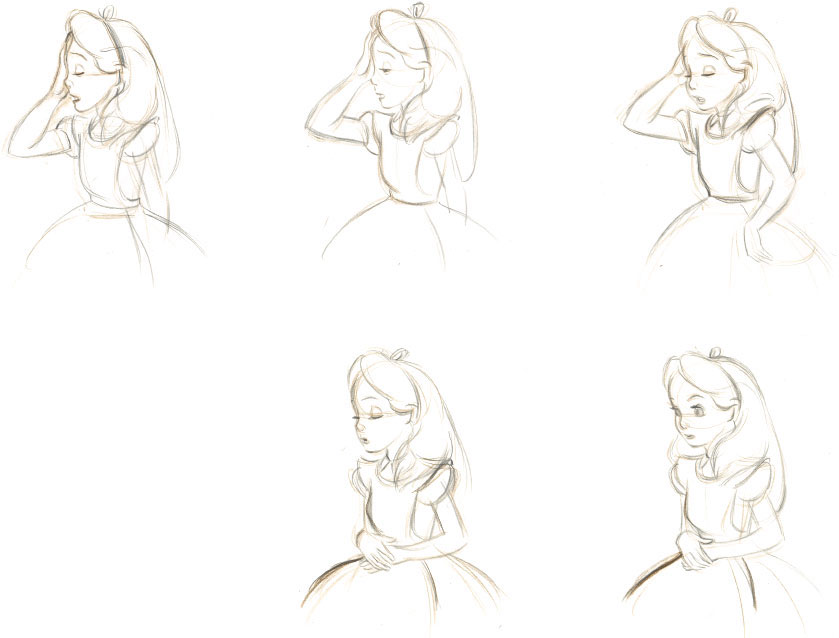

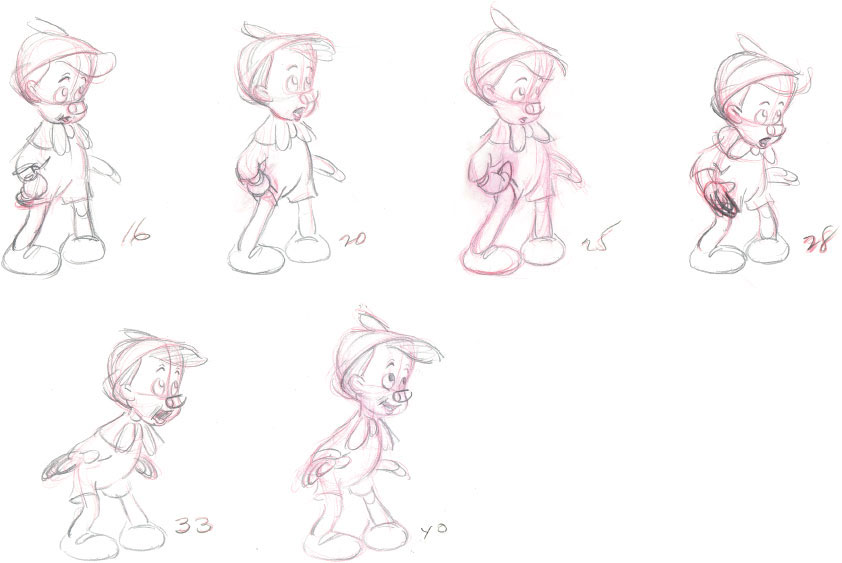

1951

ALICE

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 3, Sc. 22

Alice has gone through a lot in an effort to try and pass through a miniature door. When she reduces her size hoping she would be able to pass through, the doorknob informs her that he is locked. Ollie animated Alice’s frustrated reaction during her encounter with this strange character from Wonderland. In this close-up scene she slides her right hand up her face in an attitude of disappointment and annoyance. During this action Alice’s nose is affected by being flattened for a short moment. It is an effective way to show a soft part of her face reacting to the touch of the firm palm of her hand. This gives the illusion that the audience is watching a flesh and blood character on the screen. A subtle contact like this one makes a big difference in making a series of drawings come alive.

© Disney

© Disney

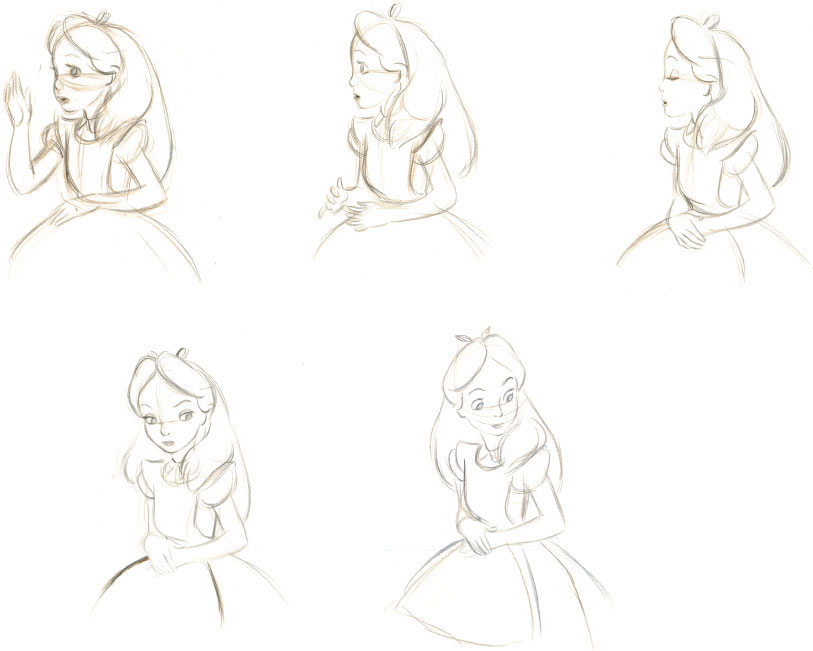

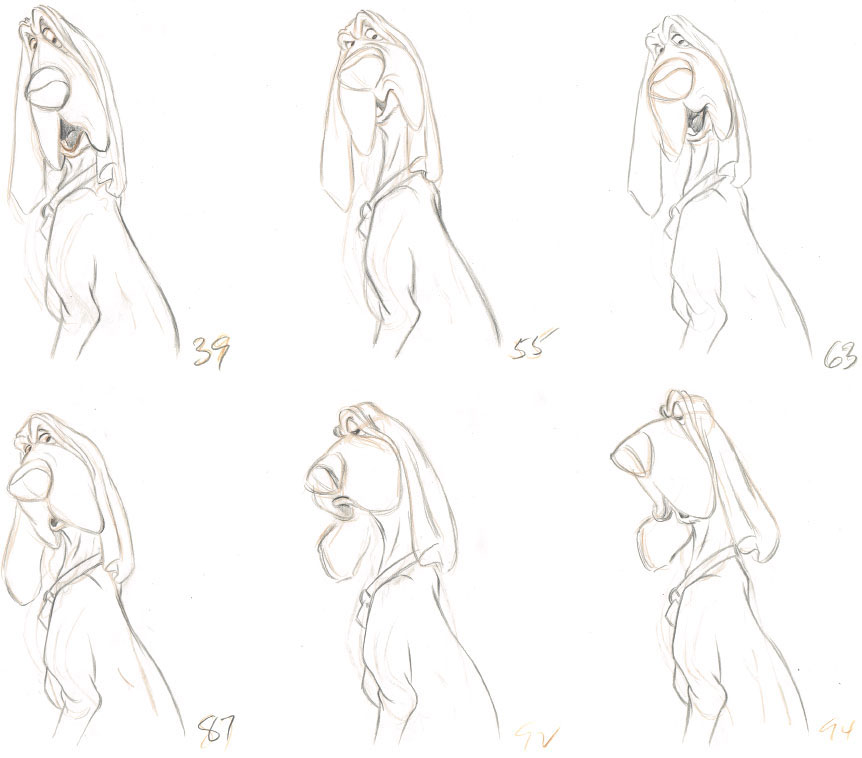

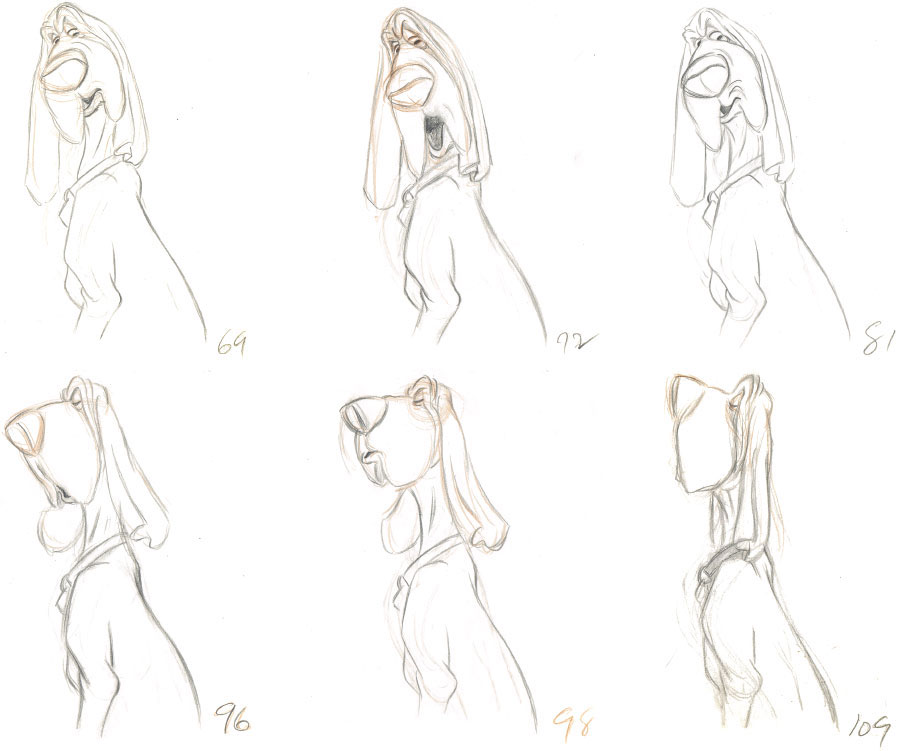

1953

SMEE

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. II, Sc. 6

As Captain Hook declares to Tinker Bell that he intends to leave the island, Mr. Smee reacts surprised, but delighted. It was his wish all along to sail away and forget Peter Pan. “I’m glad you agree, Cap’n [hic], I’ll tell the crew.”

Smee quickly hides the bottle he was enjoying inside the piano and shows his excitement through a clapping gesture. A hilarious little hiccup follows, before he leaves the scene with the intention to inform the ship’s crew.

Ollie’s acting choices reveal Smee’s misunderstanding of the situation, which is right in character.

Judging from the hasty way Smee disposes of the bottle tells us that he feels guilty drinking the wine in the first place. During the mid-sentence hiccup, his startled expression is supported by the stretch of his hat. In anticipation of his exit, Smee takes a couple of steps backward to gain some momentum. This is a beautifully textured and choreographed scene.

© Disney

© Disney

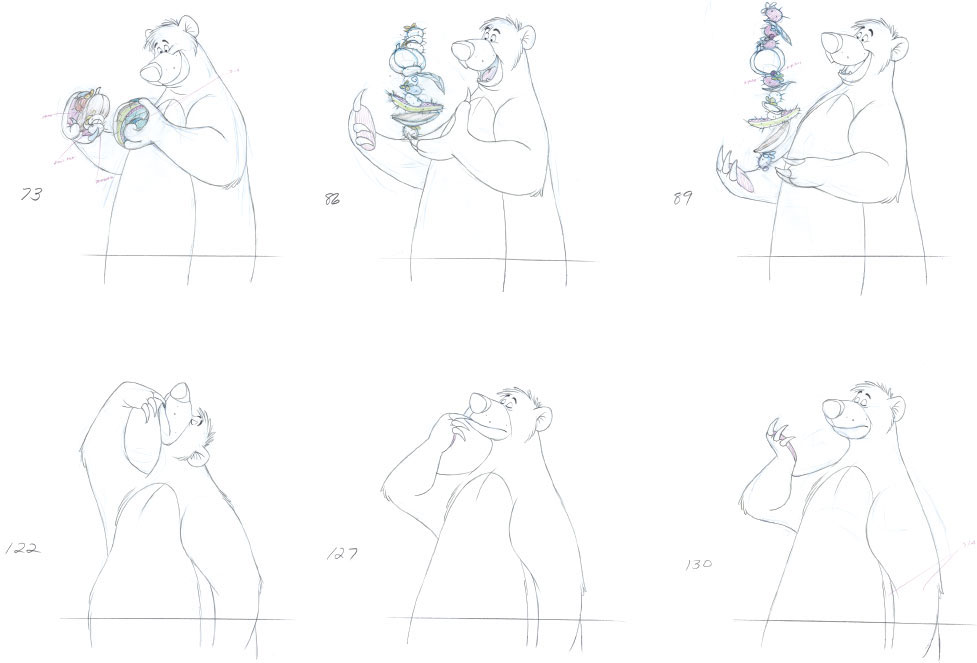

1955

TRUSTY

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. II, Sc. 17

After the embarrassing dog pound episode, Trusty and Jock pay a visit to Lady, who is now confined to a doghouse. When Tramp suddenly arrives he is being met with contempt and disregard. It is clear that Lady is not the least interested in seeing him.

Trusty offers support by telling her: “If this pussin is annoying you, Miss Lady…” Followed by Trusty: “…we’ll gladly throw the rascal out!”

Trusty’s expression is full of disdain as he says the line of dialogue over his shoulder.

Every one of his mouth shapes communicates that emotion very clearly. Since this is an old bloodhound with an extremely soft muzzle configuration, Ollie could take full advantage of this elasticity. Strong squash and stretch is applied here, as well as caricatured mouth shapes. As Trusty turns around, the motion of his long ears supports the head move nicely.

© Disney

© Disney

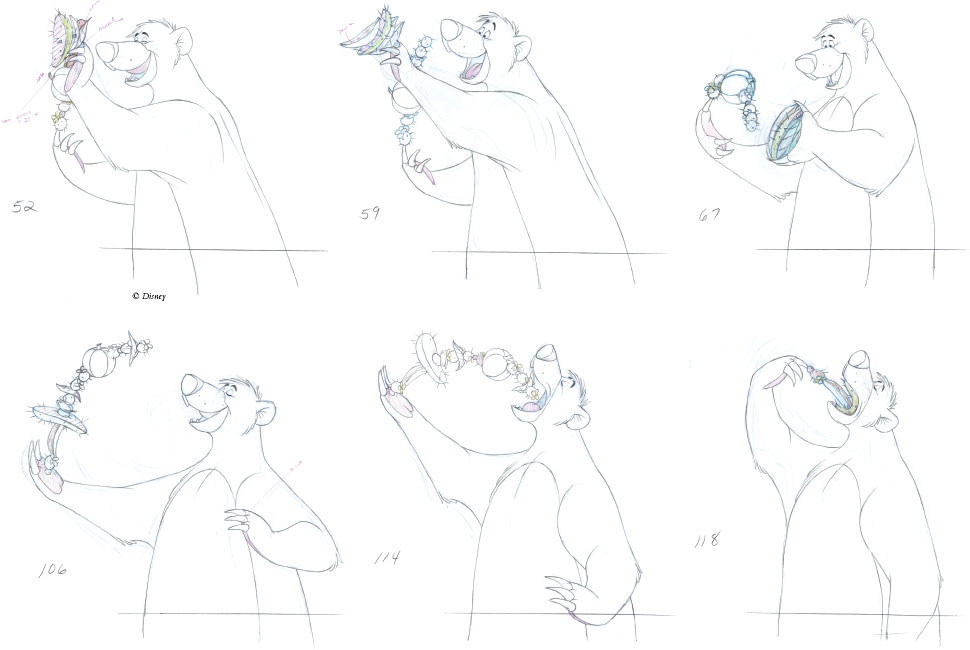

1967

BALOO

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 4, Sc. 126

During the “Bare Necessities” song number, Baloo interrupts his dancing for a moment in order to create a jungle sandwich, made up of leaves and fruit. He advises Mowgli: “Don’t pick up the prickly pear by the paw, when you pick a pear, try to use the claw.”

Like everything Baloo does, there is entertainment and showmanship in preparing this exotic snack. When both of his claws hold enough food, he arranges the chunks of fruit as if they are playing cards. By mixing and combining them, one tall eatable tower emerges, which the bear quickly devours with great ease.

All of these pieces of action are highly unrealistic and even illogical. Yet Ollie’s animation looks completely natural and believable. Any of the key poses are drawn within a clear silhouette, which makes it easy for the viewer to follow the fruit pile’s path of action, from being picked to entering Baloo’s open mouth.

© Disney

© Disney