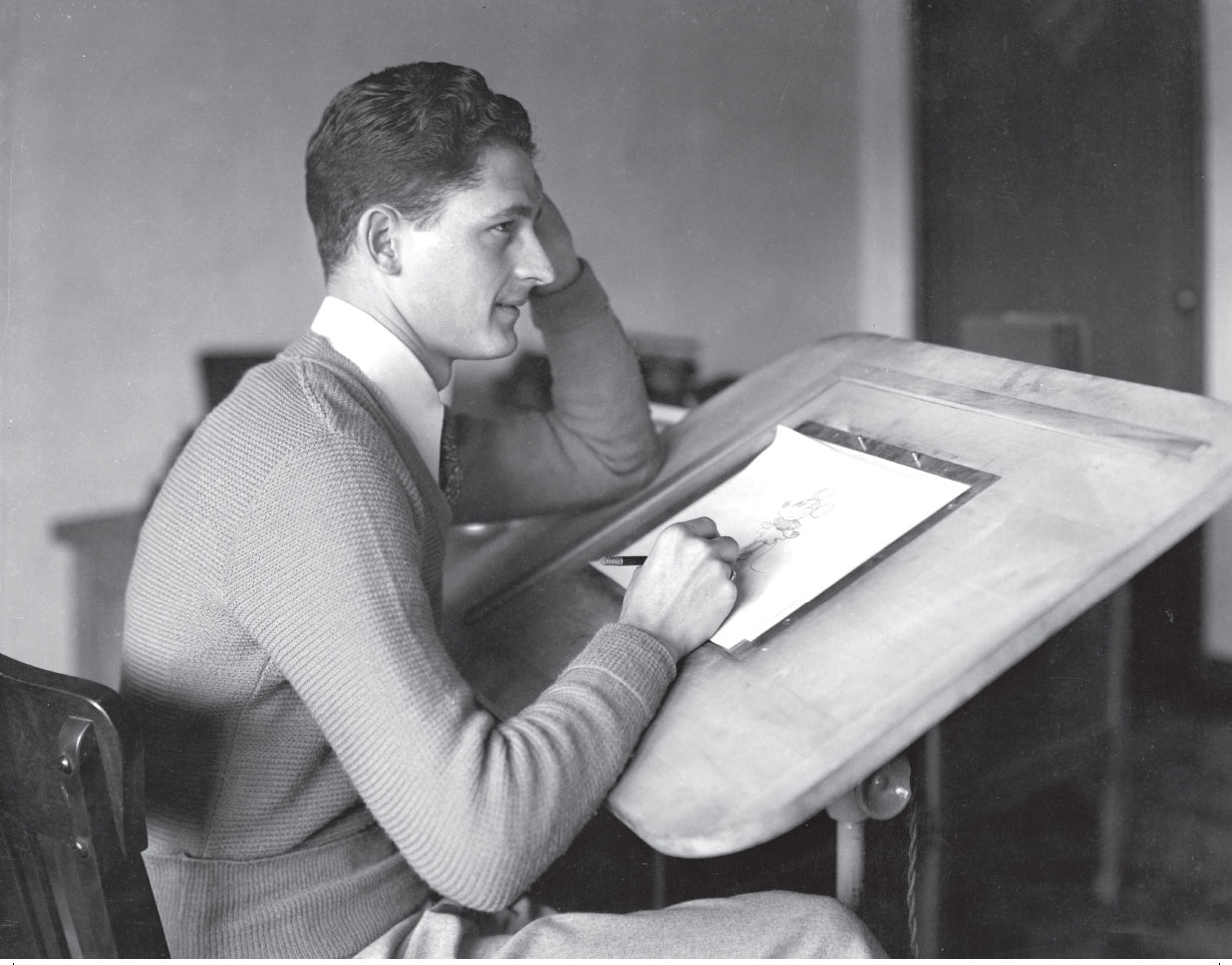

When Les Clark retired from the animation industry in 1975 he had worked for Walt Disney Productions for almost half a century. He first met Walt Disney in 1925 at the candy store he was working for part-time, as Clark was still attending high school. A couple of years later, with no formal art training but an avid interest in the new medium of animation, he asked Walt for a job.

His portfolio consisted only of a few redrawn illustrations from the popular magazine College Humor, but Disney saw something in his lively line work, and so Les was hired in 1927. He spent his first year at the studio as a camera operator. Clark also learned the craft of inking the animators’ drawings on celluloid sheets, so-called cels, before they were photographed on a painted background under the camera. Eventually he became an in-betweener on scenes with Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. When Walt Disney found himself in a feud with his film distributor, who owned the character’s rights, he refused to renew a less attractive contract and walked away from the Oswald film series. Walt was in need of a new character, and soon Mickey Mouse was born. Animator Ub Iwerks drew the first couple of Mickey shorts, Plane Crazy and The Gallopin’ Gaucho, and his assistant Les Clark did the in-betweens. But it was Mickey’s third film Steamboat Willie that resonated with audiences in a big way. Walt produced this short with sound, and the enthusiastic response was a big shot in the arm for the struggling animation studio. New Mickey films followed to great success, but Walt also wanted to diversify and started another series called Silly Symphonies, in which music played a vital role. The first one was The Skeleton Dance, which again was mostly animated by Iwerks. Clark got the chance to draw a scene in which one skeleton uses the ribcage of another one like a xylophone.

A couple of frivolous skeletons marked the beginning of Clark’s career as an animator.

© Disney

In these early days of animation, many discoveries were about to be made, and squash and stretch was one of them. By distorting the character’s face and overall body mass, the illusion of life suddenly became more believable than ever before. It seemed that by showing change within the rhythm of the character, the animated performances became much more convincing.

One character that came to life through extensive use of squash and stretch was Clara Cluck in the short Orphan’s Benefit. She plays an eccentric opera singer during a talent show that is hosted by Mickey Mouse. Clark animated her entering the stage with a weighty walk. Her hefty body parts move with overlapping motion, and the effect is entertaining and convincing. As she sings her aria, Clark again uses dramatic distortions in her body to emphasize the high notes.

Clark used strong squash and stretch on the character of Clara Cluck in the short Orphan’s Benefit.

© Disney

Les Clark had absorbed all of Iwerks’ work methods including his way of staging gags convincingly. Characters needed to be drawn in clear silhouette in order to communicate their humorous antics. There was also a surreal quality to those gags; nothing seemed impossible. When Minnie jumps out of an airplane to get away from Mickey, her panties turn into a parachute and she lands safely. Crude as this might seem today, animated gags like this got big laughs from audiences at the time. When Iwerks left Disney to open his own animation studio, Clark became the lead animator for Mickey Mouse. In 1935, Mickey starred in his first color short film The Band Concert, in which he conducts an orchestra out in the open. After several interruptions by characters like Horace Horsecollar and Donald Duck, a tornado suddenly strikes. But Mickey keeps his cool and continues to direct his musicians, even when everybody is being lifted up high in the air by the storm. Les Clark animated all of the important scenes with Mickey, whose movements needed to be in sync with the music at all times. The animation is already smoother than what Iwerks had achieved with the character early on. But Disney’s ongoing demands for improved animated performances would soon lead to breathtaking new heights in the art of character animation.

Les Clark added greater appeal and range to Mickey’s performances.

© Disney

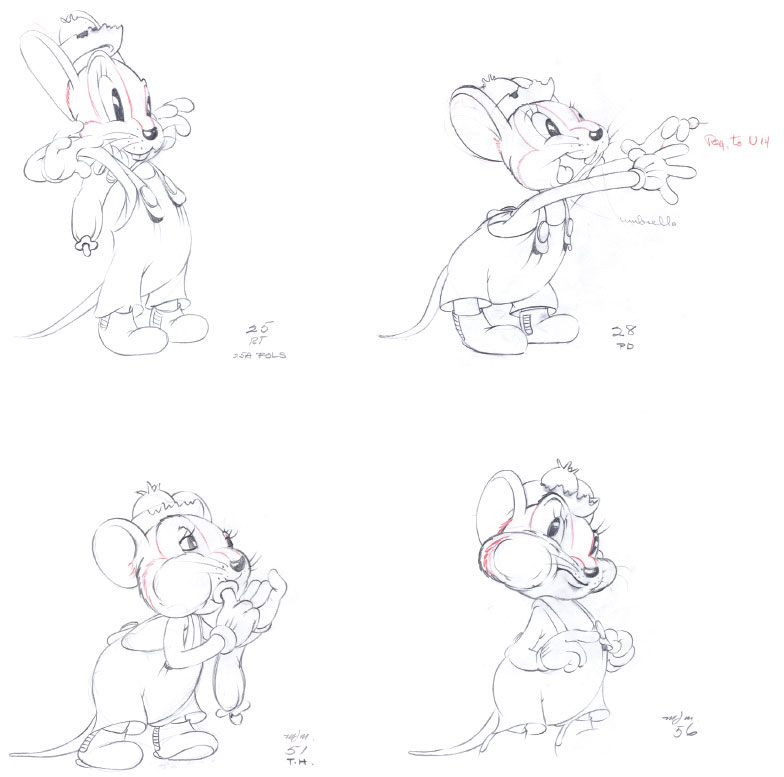

A young artist named Fred Moore had been assisting Clark’s scenes, but during the early 1930s came into his own as an animator. He was a natural, intuitive draftsman, who never seemed to struggle with any of his assignments. Everything he drew had appeal and personality. To the envy of many of his colleagues, Walt Disney encouraged his animators to study Moore’s style in order to capture some of its special charm. By 1936, Moore had redefined the design for Disney characters, and his way of drawing influenced the entire studio. One particular detail is worth pointing out; many of the early characters were given very simple eyes, usually a couple of vertical oval shapes, painted solid black. Moore created realistic eye units, in which oval white shapes were drawn with small black pupils. This resulted in a greater facial expressive range as well as subtle eye articulation. Animators Art Babbitt and Les Clark made full use of this new concept when they both animated Abner the mouse for the film The Country Cousin. Both artists also pushed the boundaries of elasticity when it came to exaggerate expressions. Clark animated a series of scenes in which the country mouse, looking at mountains of human food, can’t help himself but stuff his mouth in the broadest way possible.

Abner the country mouse with a mouthful of cheese.

© Disney

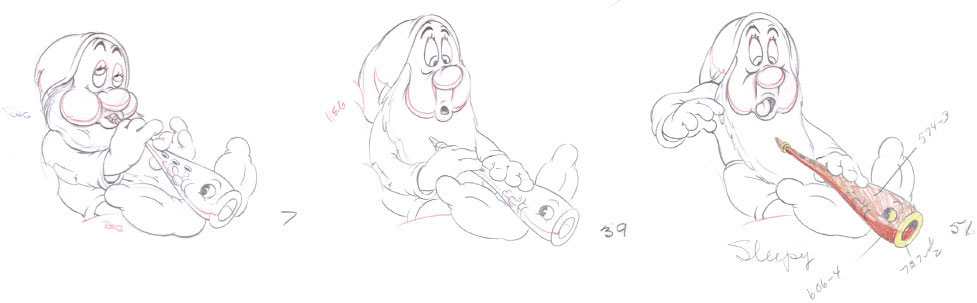

Broad as well as nuanced performances were needed to bring the group of dwarfs to life for Disney’s first feature film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Clark had the experience and the talent to animate important acting scenes. Fred Moore’s cartoony designs of the dwarfs allowed for the kind of rich, fluid movements that most animators enjoyed. During the film’s yodel song, Snow White enjoys the dwarfs’ individual musical performances, before joining them for a dance.

Clark animated several scenes of the dwarfs playing different instruments including Sleepy, who plays a flute. At one point he pauses and gets into a big yawn, when suddenly a pesky housefly inspects the inside of Sleepy’s wide-open mouth. The unwelcome visitor is quickly chased away with brisk hand-gestures. The scene is just over six seconds long, yet every bit of action reads very clearly. Enough time is given to each part of the performance: the yawn, the intruding insect, Sleepy’s realization of what is happening, and him taking action.

Clark animated Sleepy playing a flute in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

© Disney

It comes as no surprise that Les Clark got to animate many scenes with Pinocchio, the title character of Disney’s second feature. While Milt Kahl, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston supervised Pinocchio’s animation, Clark had no problems helping out wherever he was needed.

When, toward the end of the film, Geppetto is reunited with the wooden boy inside the whale’s stomach, Clark gave some insightful performances. After a big sneeze, Pinocchio’s donkey ears pop out from under his hat, shocking not only Geppetto, but Figaro the cat, and Cleo the goldfish. This is an awkward situation, and Pinocchio is at a loss for words. He holds his donkey tail, deeply embarrassed. The feeling of guilt and shame is beautifully portrayed in these poignant scenes. This is one of many Clark scenes that give us strong insight into how the character is feeling in a moment of embarrassment.

Sincere emotions help to make Pinocchio come alive to an audience.

© Disney

A very different type of assignment came along when Les Clark started to work on Fantasia: he animated a variety of fairies for the film’s Nutcracker Suite. The development of specific personalities was not required, since we never get to know these nature sprites. Clark based their elegant movements on hummingbirds, which gave their flying patterns a beautiful stop-and-go feeling. These delicate fairies were drawn with sizable wings and long legs, which helped to define charming feminine poses.

Delicate drawing and subtle timing added a graceful touch to the fairies.

© Disney

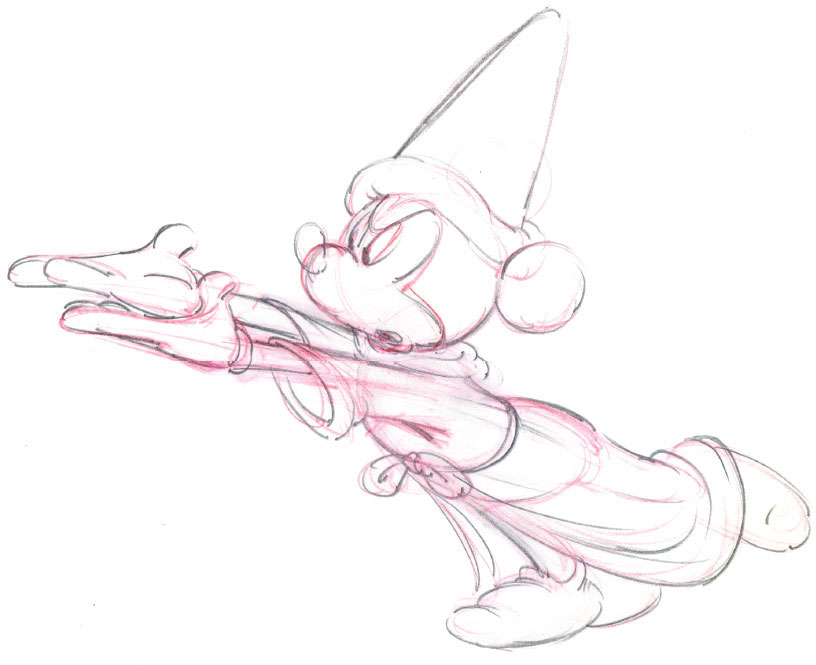

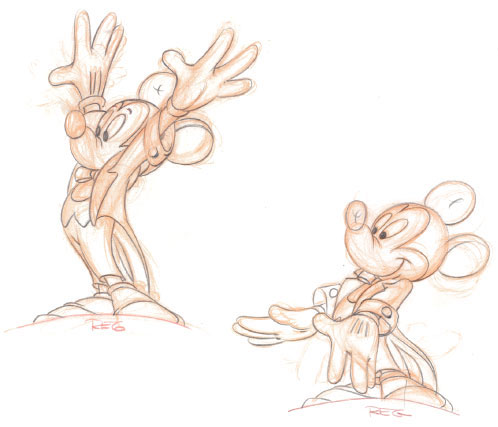

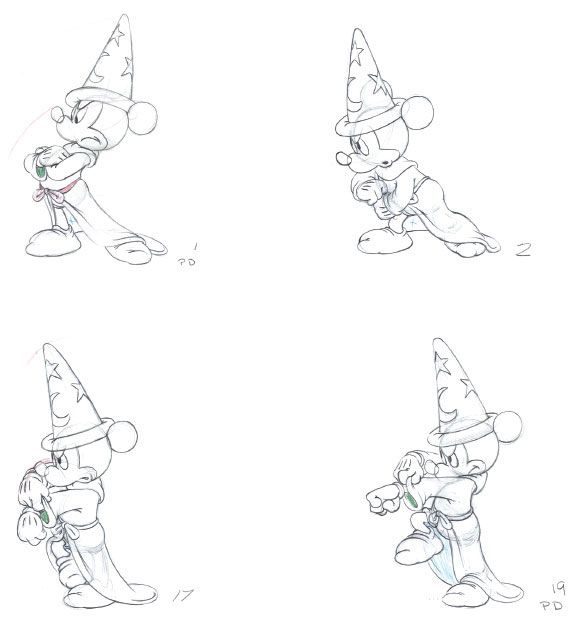

Clark also animated an important part of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. When Mickey Mouse commands the broom to come to life, he does so with great intensity. While his body is stretched in a strong forward arch, his fingers flutter fiercely. This convulsion-like movement heightens the scene’s tension and makes us believe that there are real magical powers at play. This is an extraordinary piece of animation, dramatically staged and perfectly timed. It also shows an intensity in Mickey’s emotions that had not been seen before. His attitude changes after he succeeds in making the broom follow him to a fountain. Clark animates Mickey here with a confident attitude, as he hops along and leads the way. The movement is made interesting by the addition of complex overlapping action in Mickey’s oversized coat. Realistic designs of the fabric’s folds perfectly enhance the character’s bouncy motion.

In The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Clark gave Mickey an intensity that had not been seen before.

© Disney

While Mickey might have been conducting the universe in Fantasia, in the 1942 short film The Symphony Hour he is in charge of an impaired orchestra, which consists of classic Disney characters like Donald Duck, Goofy and Horace Horsecollar. Mickey had gone through a few design changes during the early 1940s. The inside of his ears were painted in grey, and they almost moved dimensionally. In previous films his perfectly round ears just slid across his upper head. While his torso was drawn a bit smaller, more volume was given to his nose, hands, and feet. Les Clark animated the opening scenes when the musicians try very hard to follow Mickey’s lead. As an animator it would be a challenge to find interesting ways for the conductor’s movements, particularly when the beat is fairly even, as it is in this section of the film. But Clark varies Mickey’s hand gestures just enough to give the animation texture. Each hand action needs to end one or two frames ahead of the actual sound in order to feel in sync with the music.

With The Symphony Hour, Clark showed again that he was an expert at animating Mickey Mouse.

© Disney

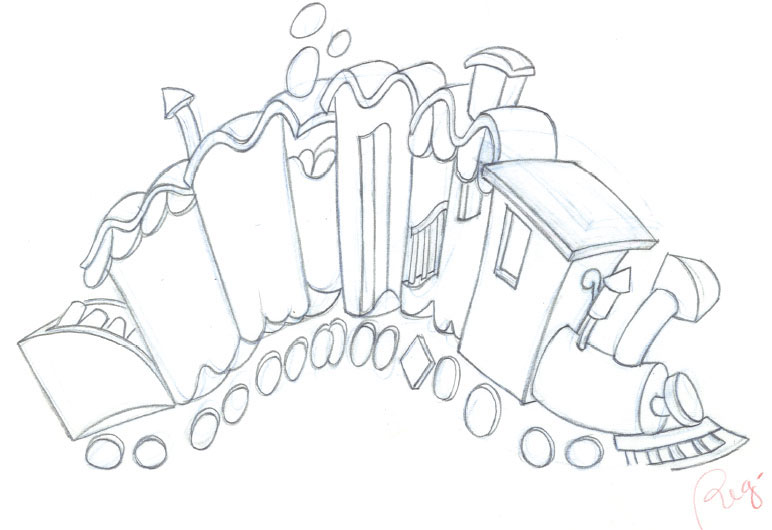

Music also played a role, when it came to bringing a little train to life during a short section from the film The Three Caballeros. José Carioca invites Donald Duck to join him on a train ride to the city of Baia. Les Clark’s animation of the spirited locomotive is charming, as it chugs along to an energetic musical beat through a landscape that is reminiscent of a children’s book illustration. The movements evoke the alluring simplicity found in the work of Clark’s former mentor Ub Iwerks. All goes well on the journey until the naughty Aracuan Bird draws separating tracks on the ground, which causes the little train to lose all his wagons for a few tense moments, until they all get reunited near the train station. This train goes through real human emotions, from having fun to anxiety and then relief at the end of the sequence. No arms or legs needed, not even a face. Yet Clark articulates these feelings by offsetting the various locomotive parts in a way that communicates a definitive state of mind.

The train in The Three Caballeros displays emotions, despite having no limbs or face.

© Disney

During the Second World War, box office revenues shrank, and the studio had to put ideas for more ambitious storytelling on hold. Disney continued producing feature-length package films, which consisted of a number of shorts. Clark continued animating on film titles like Make Mine Music and Song of the South, but it wasn’t until Fun and Fancy Free that he found a signature assignment. The Mickey and the Beanstalk segment featured an unusual character, the Singing Harp. This combination of fairy and musical instrument presented the animator with limitations as far as motion goes. Only her upper body could move, the rest was attached to the wooden harp. Clark used elegant arm movements, as she points out to Mickey where Willie the Giant hid the key that is needed to free Goofy and Donald. Subtle, beautiful drawing and graceful animation made this unique character memorable.

Clark created a memorable character in the Singing Harp from Mickey and the Beanstalk.

© Disney

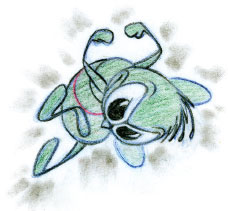

Another curious assignment came along with the film Melody Time. It featured a section called Bumble Boogie, a jazzed up version of Rimsky-Korsakov’s composition “The Flight of The Bumble Bee.” This bee character flies through a “musical nightmare,” as the narrator explains at the short film’s opening. In his animation, Les Clark needed to keep up with the score’s high energy and rhythm.

Appealing design and energetic timing helped to make this tiny character come alive.

© Disney

The visuals are among the most surreal scenes ever animated at Disney. The bee is being pursued and attacked by unfriendly flowers, musical instruments, and abstract lines. At one point during the chase he decides to fight back and brings this horrid dream to an end. There isn’t much character development involved, but Clark still makes us feel sympathetic toward the little bee.

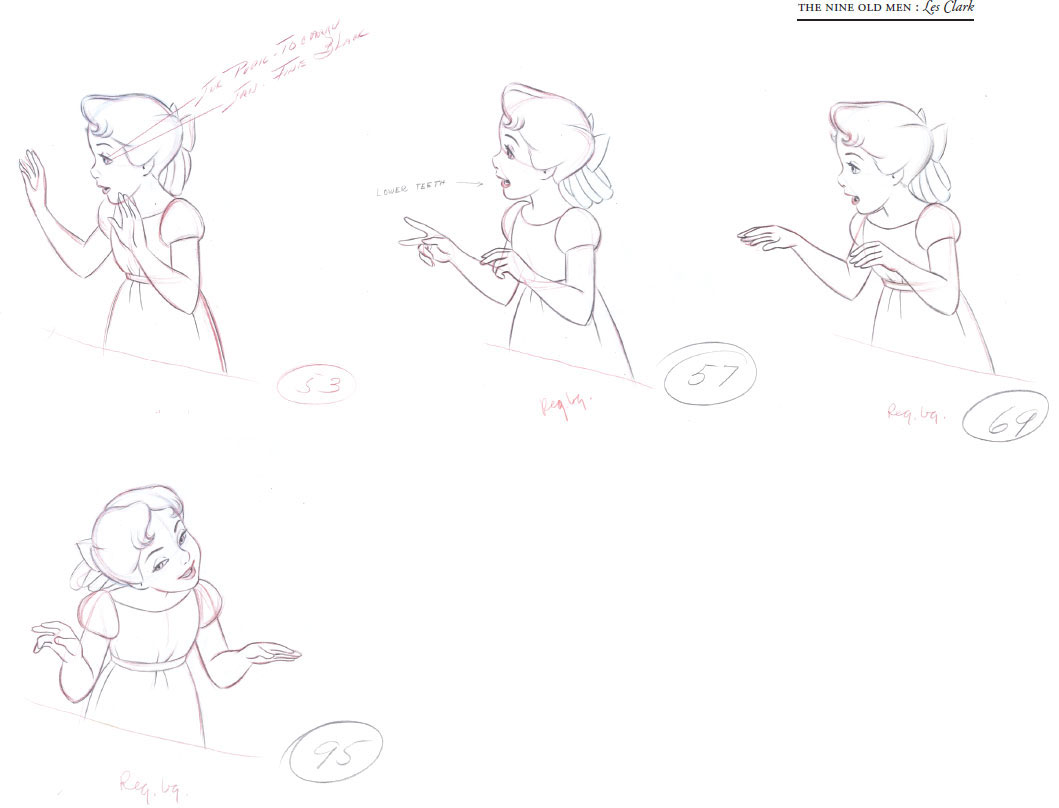

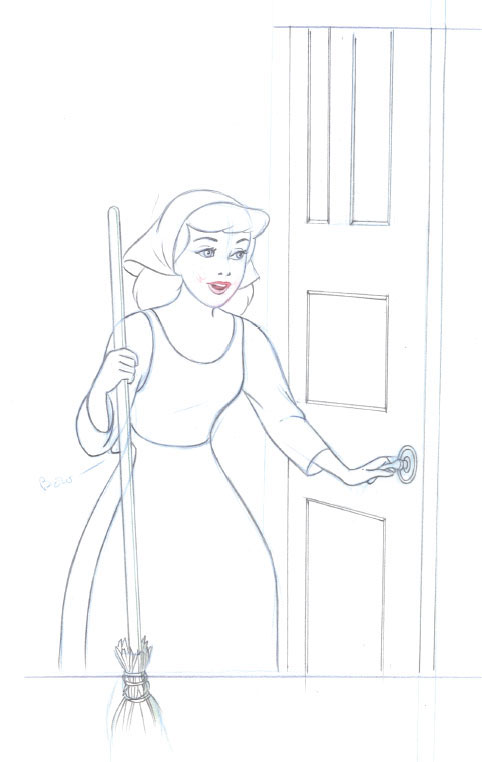

Almost being cast against type, Les Clark joined colleagues Eric Larson and Marc Davis in animating the very realistic and beautiful Cinderella. The live-action reference, featuring actress Helene Stanley, proved to be both helpful and a curse. The footage provided the animators with acting patterns, but how should these movements by a real woman be translated into successful graphic motion on paper? There is an essence, an emotional core that needs to be found and enhanced for an animated character. Among many scenes with the film’s title character, Clark animated her delivering an invitation from the palace to her stepmother. When the letter is being read out loud, Cinderella finds out that every eligible maiden is to attend the royal ball. She states, “That means I can go, too.” Her stepmother plays along and responds, “If you find something suitable to wear!” The following scene shows Cinderella with such relief and joy, she is alive in the most convincing way. Her emotional state could not have been drawn and animated any better, as she says, “Oh, thank you, stepmother,” before exiting. There is a truth and honesty in the way Clark handled the scene, as if he felt the character’s hope and joy.

Clark’s animation of Cinderella proved that he was perfectly able to deal with difficult, realistic assignments.

© Disney

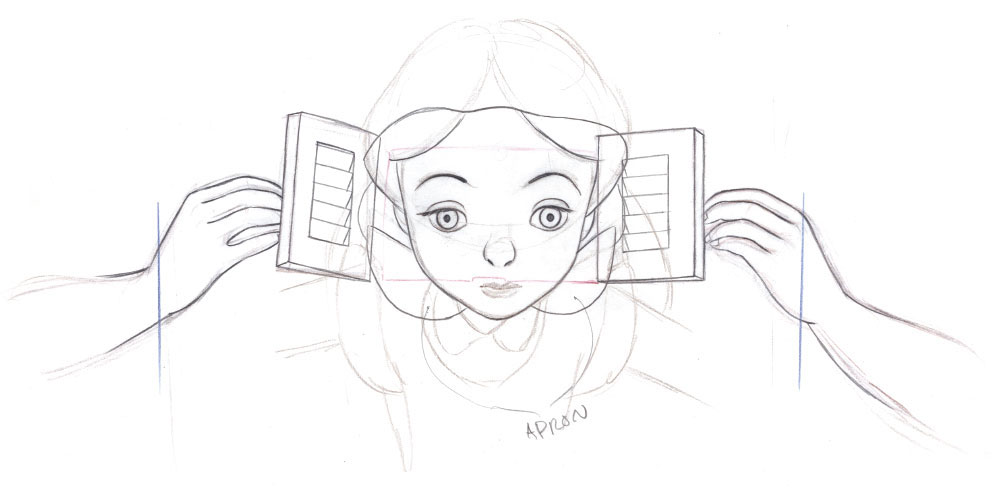

His strong animation of Cinderella led to Clark’s involvement with Disney’s next leading lady, Alice from the film Alice in Wonderland. The technique would be similar, making intelligent use of live-action reference footage in order to present a young girl dealing with adverse situations.

One of his sequences shows Alice growing dramatically in size inside the White Rabbit’s house, to a point where her arms and legs are sticking out of doors and windows. This presented certain staging challenges. On the one hand, Alice needed to look uncomfortable and awkward under these circumstances and, on the other hand, she needed to fit into this small house in a believable way.

Dramatic perspectives on humans are not an easy thing to achieve, but Clark’s talents as a draftsman helped to present unusual up and down shots very successfully.

Clark tackled the challenge of fitting an enormous Alice into the White Rabbit’s house.

© Disney

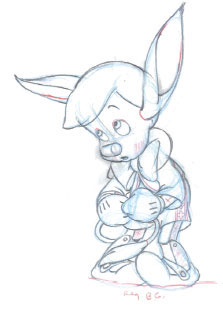

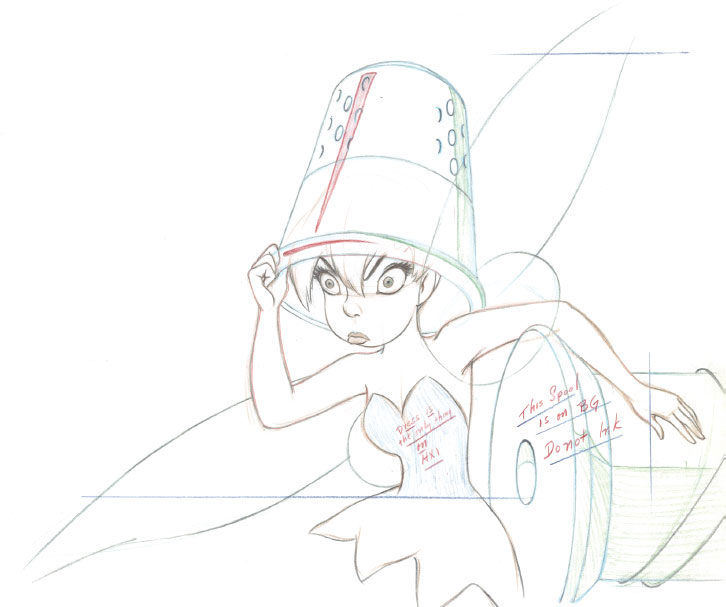

Having worked well with Marc Davis before, Les Clark joined his colleague again to help animate scenes with Tinker Bell, the emotional fairy in the film Peter Pan. While Davis did her introductory scenes, Clark drew Tinker Bell after she accidentally ends up trapped in a drawer. When Wendy charms Peter Pan during conversation, Tink knows that she is not going to like this girl. In a close-up scene, we see her lifting up a thimble very slowly to reveal her face. She literally turns red, full of jealousy.

Even though Marc Davis supervised the animation of Tinker Bell, Les Clark did not mind being the second-in-command.

© Disney

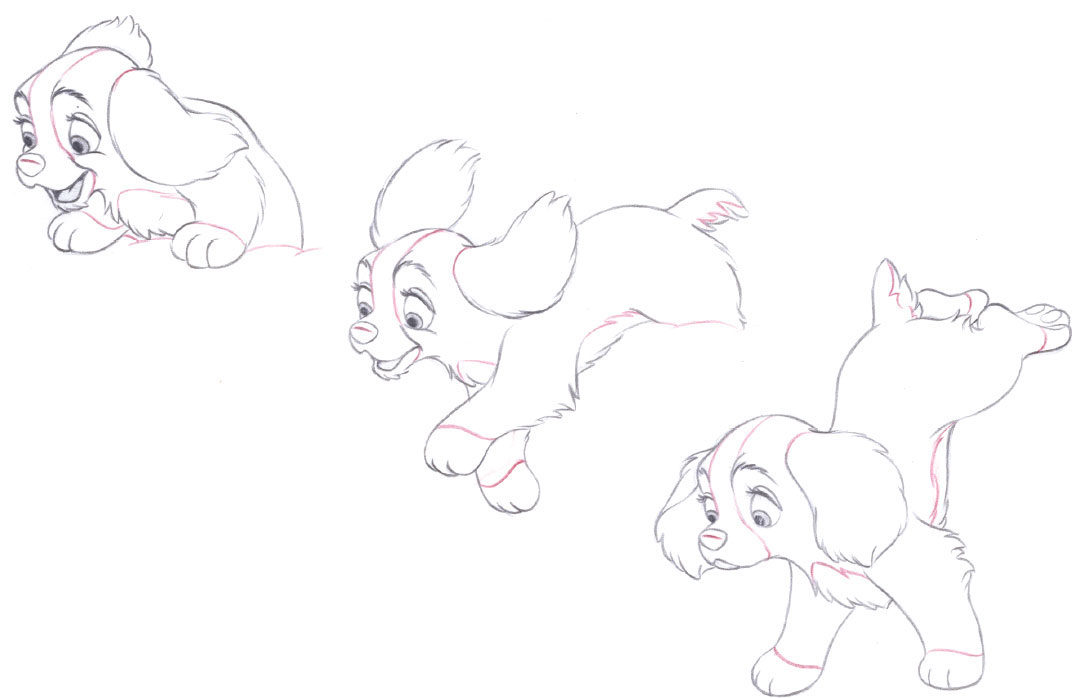

After a string of animated female characters, Les Clark switched gears on his next assignment for the film Lady and the Tramp. We see his work very early on in the film when Lady as a puppy refuses to be separated from her new owners at night. During several attempts, Jim Dear tries to make Lady stay downstairs by locking her in a room, but she finds new ways to break free. A daunting staircase separates her from the humans’ bedroom upstairs. Undeterred, she goes on the daunting uphill journey, one step at a time. Clark’s charming animation contains all the clumsiness of a real puppy. Her feet can’t quite keep up with her movements. Being so young she is still uncoordinated, and that is where the entertainment lies. With each jump up the stairs her feet slip once or twice, which shows great determination to get to where she wants to be.

Eventually she reaches the upstairs bedroom, and from then on sleeps on the bed next to the Dears.

Clark’s final animation before moving into other areas of animated film production.

© Disney

Walt Disney chose three of his Nine Old Men to become sequence directors for his ambitious production of Sleeping Beauty. They were Eric Larson, Woolie Reitherman, and Les Clark.

As older directors were retiring, it was time to fill those top spots with artists who knew animation and Disney’s philosophy about filmmaking. Among the sequences Clark directed was the very complex opening of the film. Big crowds make their move toward King Stefan’s castle to take part in Princess Aurora’s birthday celebration. According to scene planner Ruthie Thomson, those scenes were the most difficult to coordinate, partly because of so many different cel levels. Maleficent’s powerful entrance is also a part of the sequence. After Sleeping Beauty, Eric Larson went back to animation, Woolie Reitherman stayed on as director and eventually producer of Disney feature films, and Les Clark was put in charge of directing special projects like the educational film Donald in Mathmagic Land. His last project was overseeing the 1974 production of Man, Monsters and Mysteries, an entertaining film about the Loch Ness Monster myth. Les Clark was the only artist from Walt’s first generation of animators who kept up with the changes and demands at the studio throughout the decades. He knew early on that Disney wanted better-looking animation, often more realistic draftsmanship, and nuanced performances. Clark took advantage of all the in-house art classes on offer in order to better himself. Even in later years he would finish his work at the studio then drive to an evening school for courses in portrait and landscape painting. The level of artistry kept rising at Disney, and Les Clark made every effort to keep up and improve his skills. He is the least known of the Nine Old Men, but hopefully his body of work shown here will rectify this.

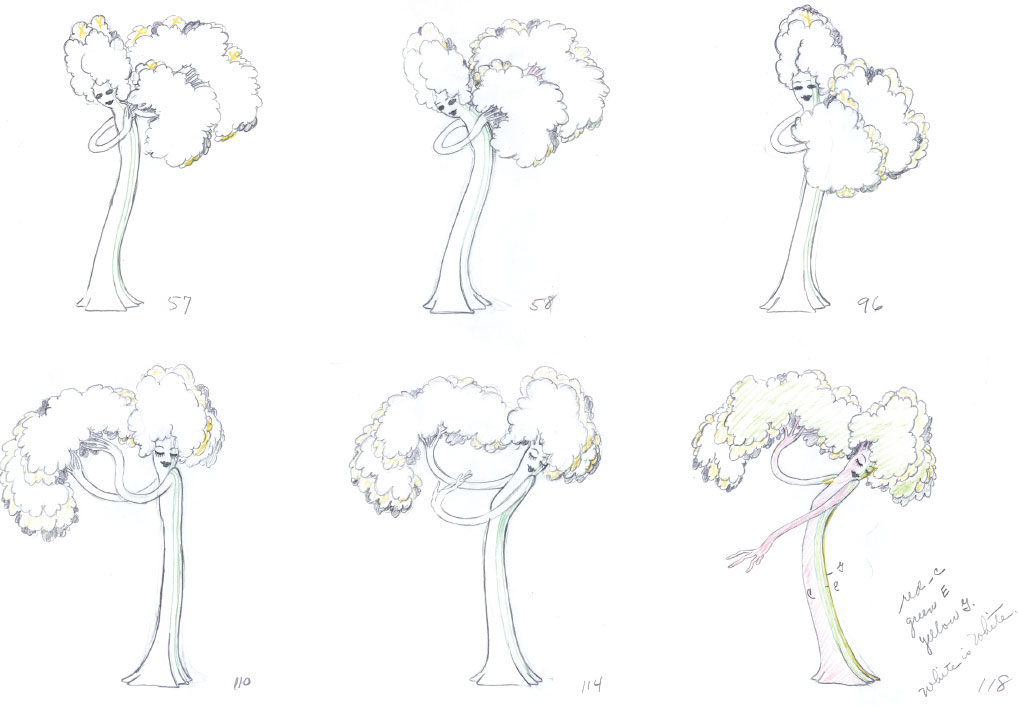

1932

WOMAN TREE

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Sc. 48

What a challenge this assignment must have been; creating a female personality out of a tree wouldn’t be an easy task. But Clark, who had earlier developed subtle feminine qualities for the character of Minnie Mouse, was perfectly cast. By bending the tree trunk according to human anatomy such as the hip, knees, and neck, he succeeds in achieving elegant poses that the audience identifies as a young woman.

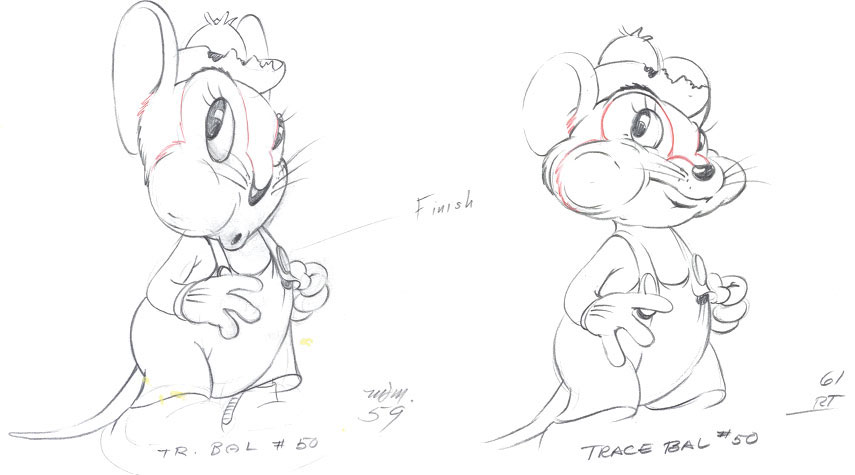

1936

ABNER MOUSE

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Sc. 14

After the mice cousins arrive in front of the oversized human buffet, city mouse Monty nibbles on a small piece of cheese in a fine dining manner. By contrast country mouse Abner grabs a piece of cheese bigger than his head, and shoves it into his mouth. As he chews, his full hamster-like cheeks squash and stretch severely in a demonstration of his enormous appetite. It is astounding to see how far Clark goes with expressions and volume shifts. By showing these bad, yet funny table manners a clear difference is established between these two characters.

© Disney

© Disney

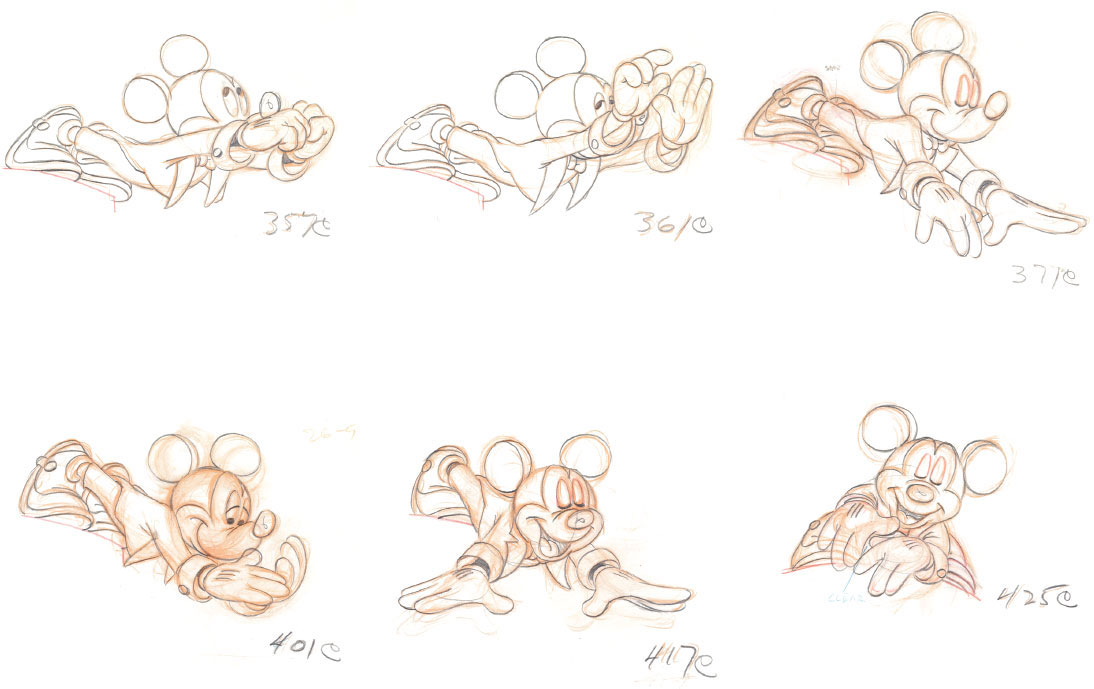

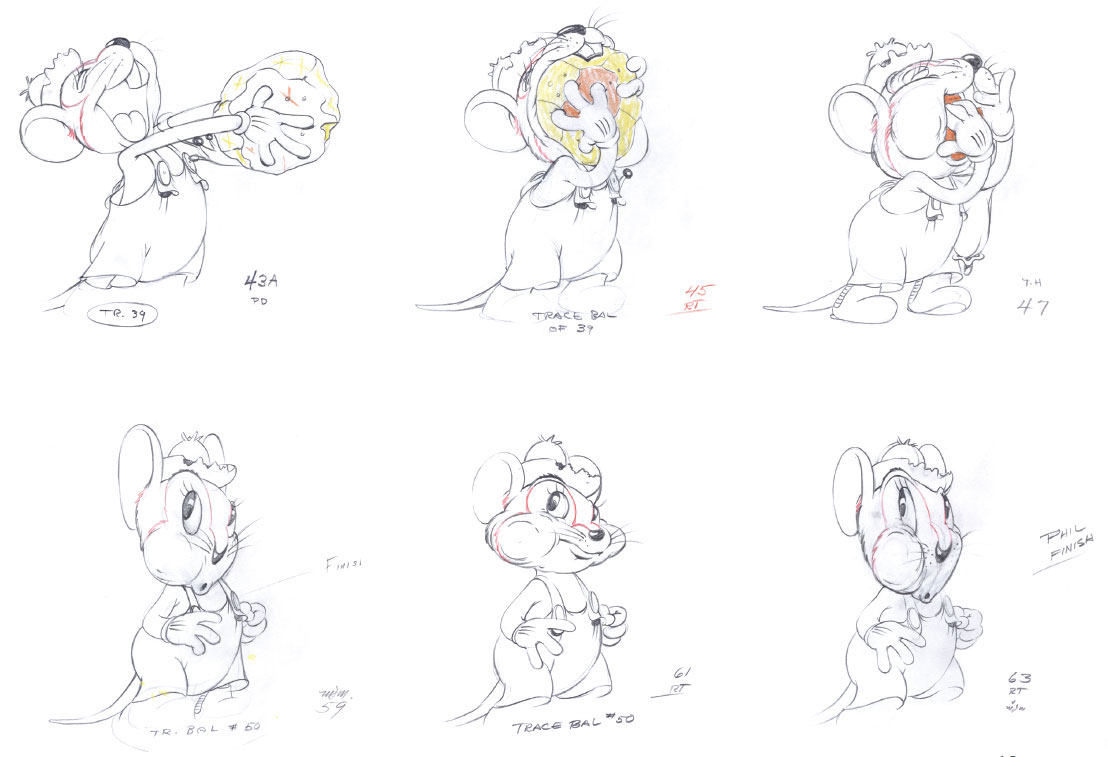

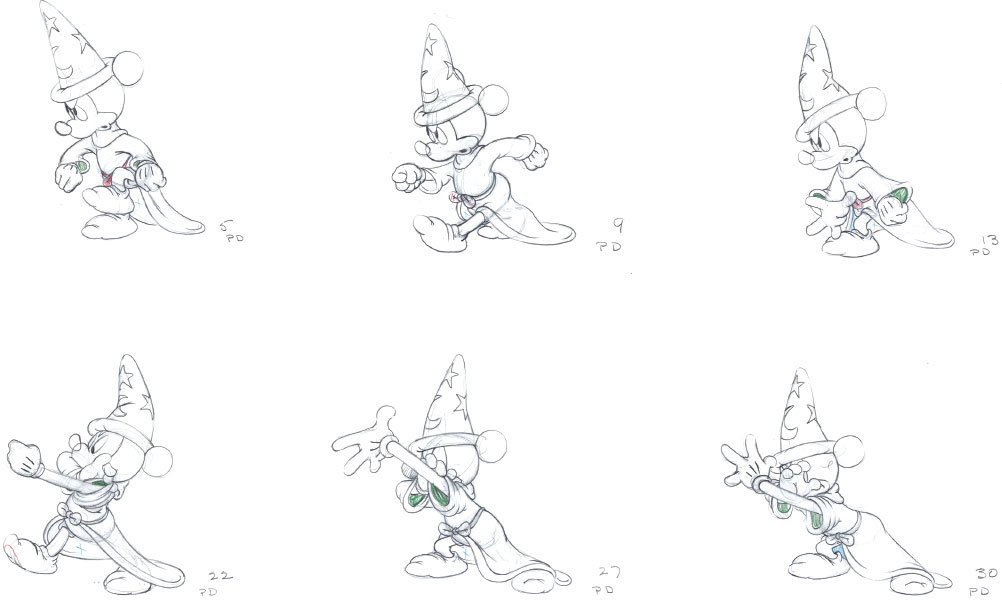

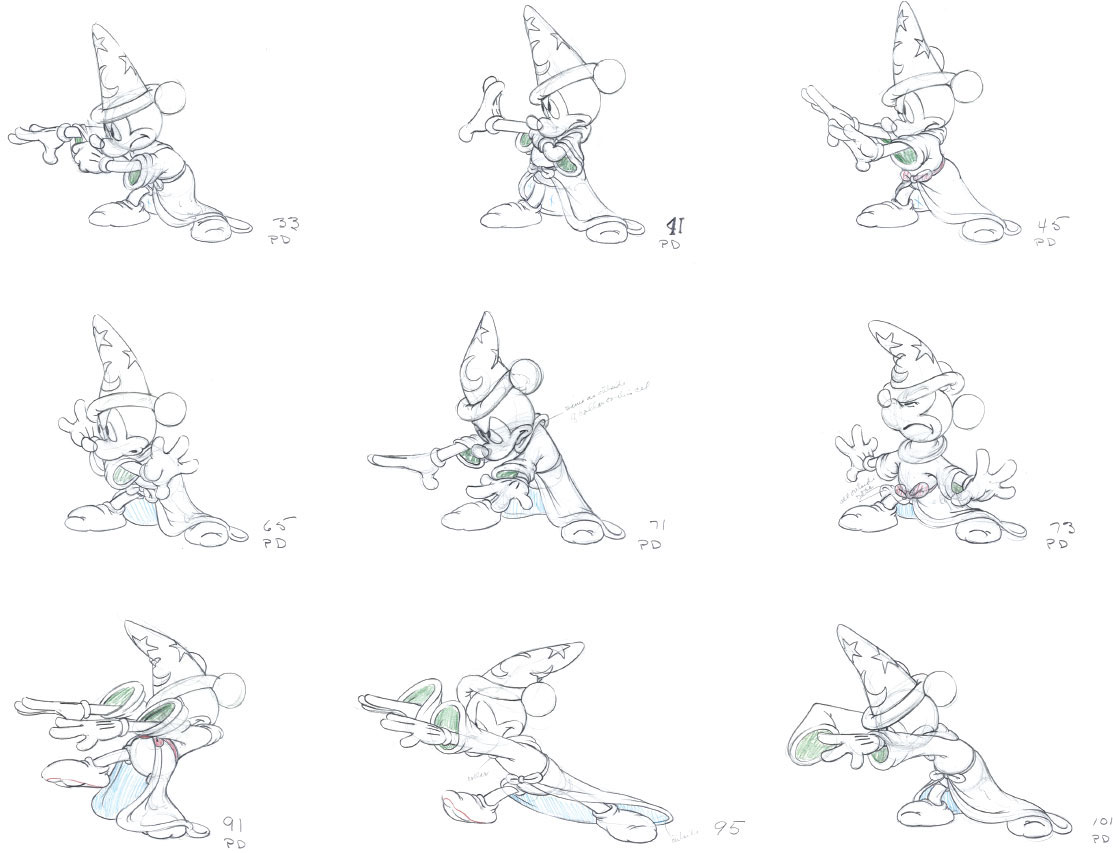

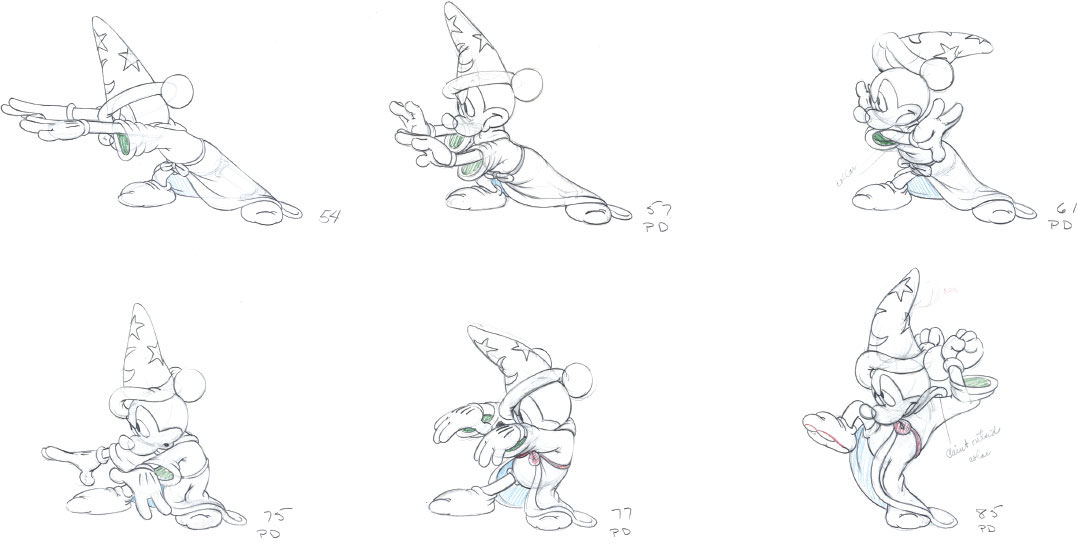

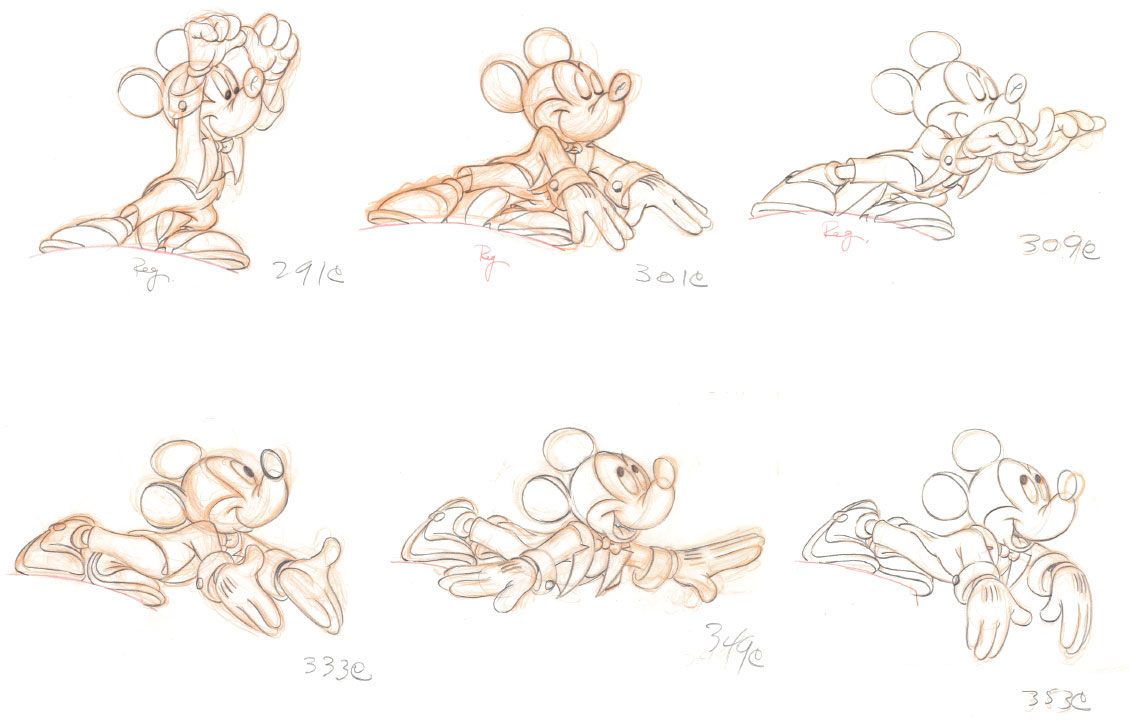

1940

THE SORCERER’S APPRENTICE

MICKEY MOUSE

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 7, Sc. 11

Scenes like this one prove that Les Clark was one of the best Mickey Mouse animators. Mickey’s forceful actions show serious determination, yet there is still an element of humor present. He repeatedly rolls up his long sleeves because they get in the way of his gesturing. His oversized outfit is a metaphor for someone who is in over his head. Clark paid close attention to how Mickey’s hands are drawn, since they are the primary force in the scene. They retain the expressiveness of human hands, even with one finger missing.

© Disney

© Disney

© Disney

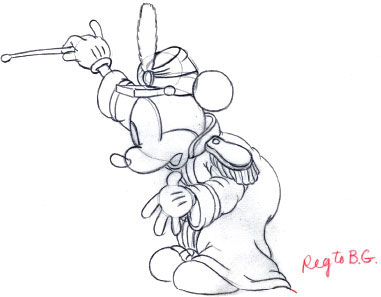

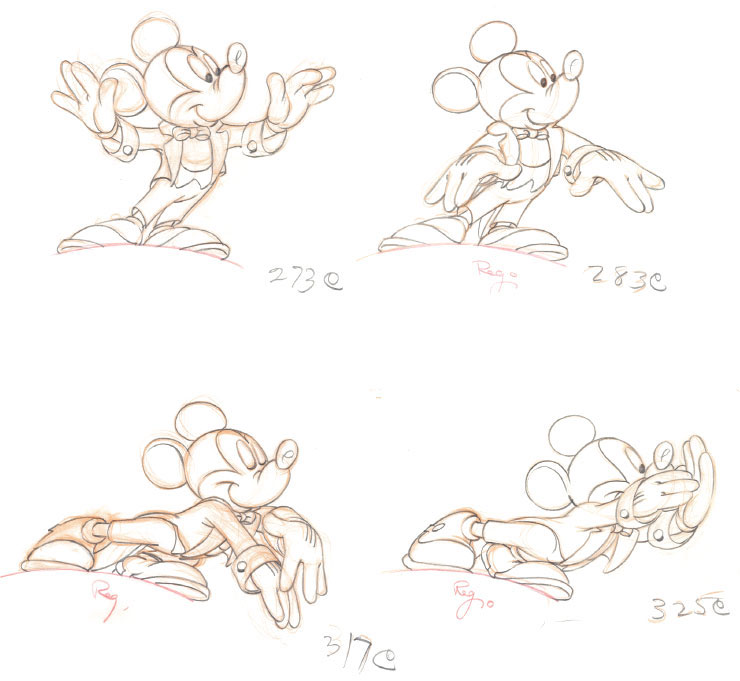

1942

MICKEY MOUSE

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Sc.6

Another beautiful piece of animation by Les Clark featuring Disney’s most iconic character, as he conducts an orchestra. His extraverted gestures are perfectly timed to the music and are reminiscent of his performance in Fantasia.

At one point during the scene the music quiets down, and Mickey leans way forward in order to get closer to the orchestra. From a physical point of view he should actually fall down, because these poses are completely off-balance. Yet this exaggerated staging communicates that Mickey’s movements are not limited by realism. As a cartoon character he can lower himself down toward his musicians as no live actor could. If the animation is entertaining the audience will believe it.

© Disney

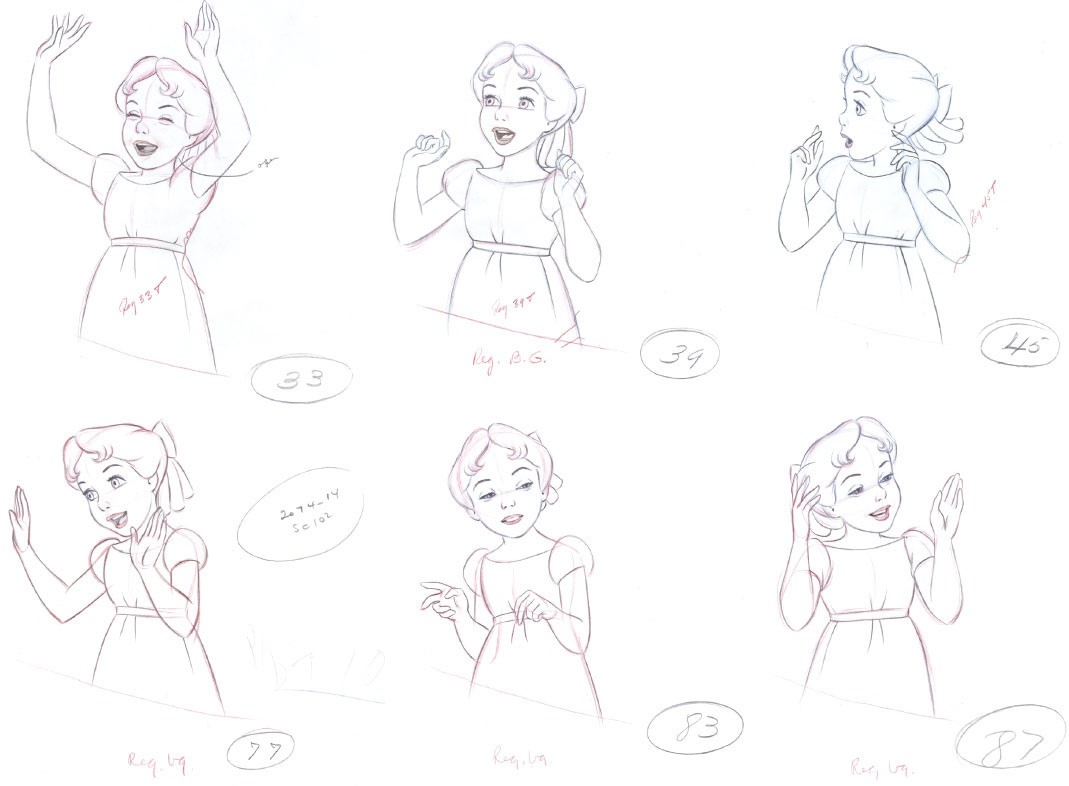

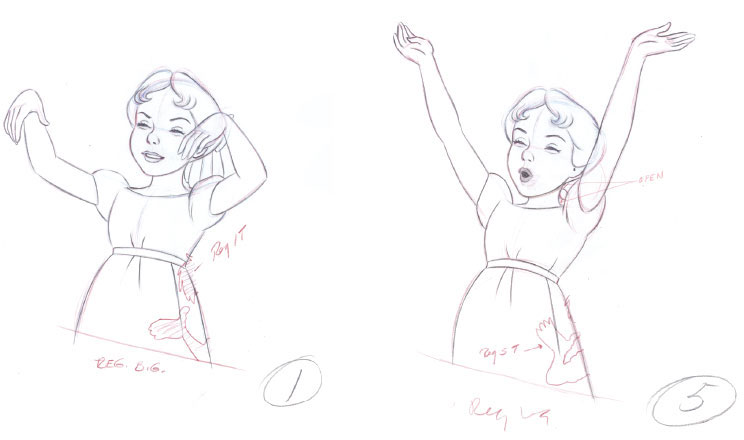

1953

WENDY

CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 14, Sc. 102

Since all of Wendy’s scenes were based on live-action reference, it was up to the animator to find the essence in the live performance and turn it into graphic motion.

Wendy along with her brothers and the Lost Boys celebrate the fact that Captain Hook admitted to being a codfish: “Hurray… Hook is a codfish, a codfish, a codfish…”

In this scene Clark is animating to the rhythm of the sung lines of dialogue. But there is something about Wendy’s head tilts that show she is really enjoying Peter Pan’s victory over Captain Hook in a kind of impish way.

© Disney

© Disney