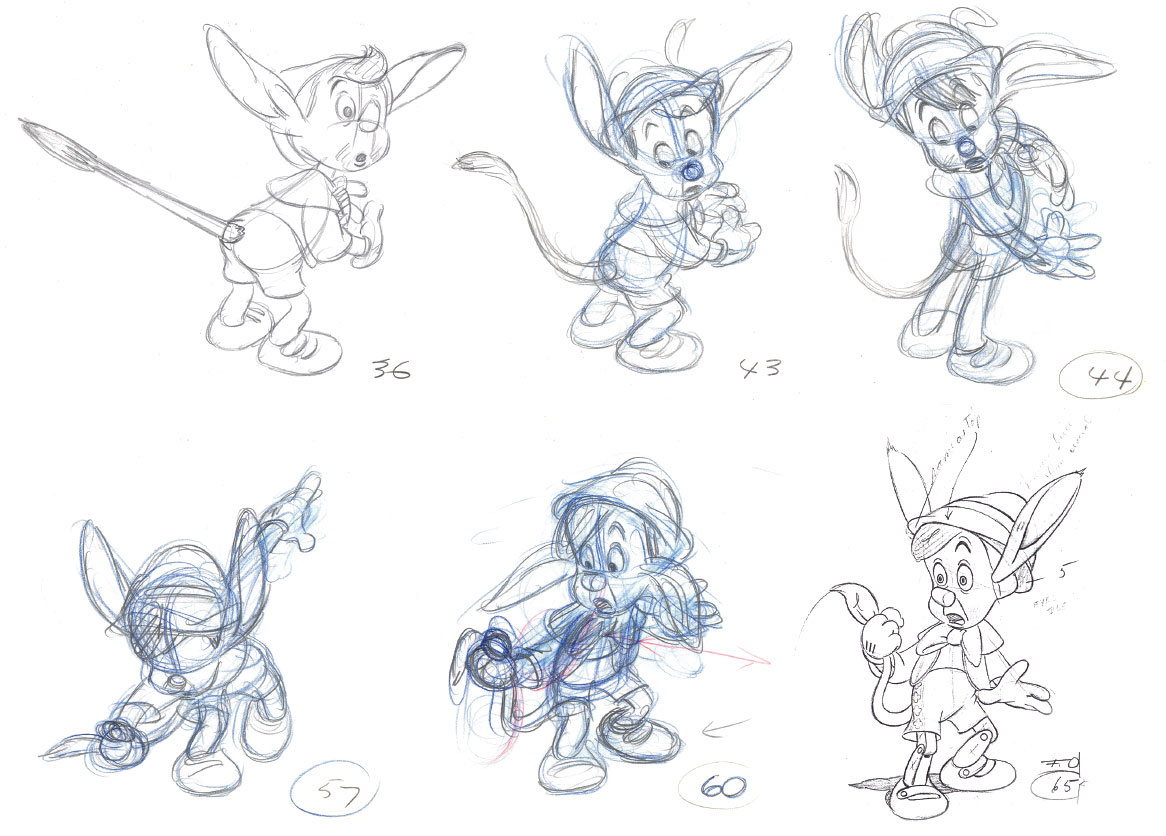

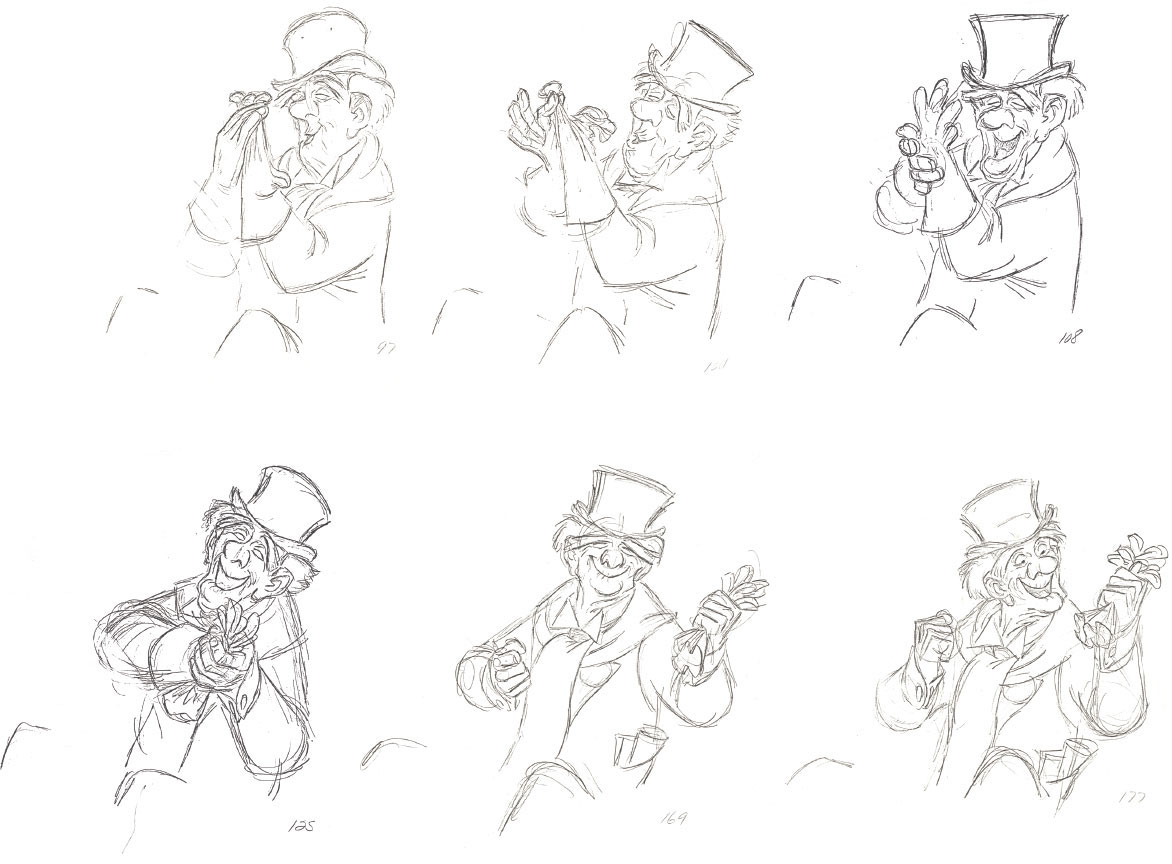

Animator Milt Kahl wasn’t happy with the way the character of Pinocchio was coming along in late 1937. During a meeting he voiced his disapproval; the design just did not look appealing to him.

He received a certain look from other artists in the room, then one of the directors, feeling somewhat annoyed, asked Milt to put his pencil where his mouth was.

So the 28-year-old animator went to work, trying to prove that he was perfectly able to improve on the existing design of Pinocchio. Milt’s approach went in a new direction, his drawings showed the character as a charming little boy, who just happened to have joints like a marionette. The fact that he was made out of wood was of secondary importance.

It turned out that Walt Disney just loved Milt’s new designs, and subsequently promoted him to supervising animator for Pinocchio. Eventually Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas joined the unit that would be responsible for animating important personality sequences with the title character.

Early design concepts and Kahl’s improved look for the character.

© Disney

Starting with Pinocchio, Walt relied more and more on Milt Kahl’s extraordinary draftsmanship and his sense for designing characters.

Ollie Johnston stated years later that Milt’s drawings always stood out and showed the personalities in a very believable way. He added: “I’ve been called crazy, but I do believe that Milt draws as well as Michelangelo.”

Walt Disney was very lucky to have a master draftsman on staff, and Milt Kahl was fortunate to join his studio at a time when his special talents thoroughly lent themselves to the demands of this new art form. “I turned out to be just perfect for this medium,” Milt pronounced confidently during an interview in the early 1980s. Earlier he told assistant Dave Michener: “I’m the best draftsman around here—that’s not bragging, that’s a fact!”

Even before the production of Pinocchio, Milt had made a name for himself as a class animator. His work on short films like Ferdinand, the Bull and The Ugly Duckling caught the attention of his boss as well as his colleagues.

This charming rough drawing of young Ferdinand shows Kahl’s confidence with a character, whose anatomy is based on the real animal.

© Disney

The sad attitude of the little duckling communicates a level of pathos rarely achieved before in animation. Milt chose this slow, aimless walk to portray loneliness.

© Disney

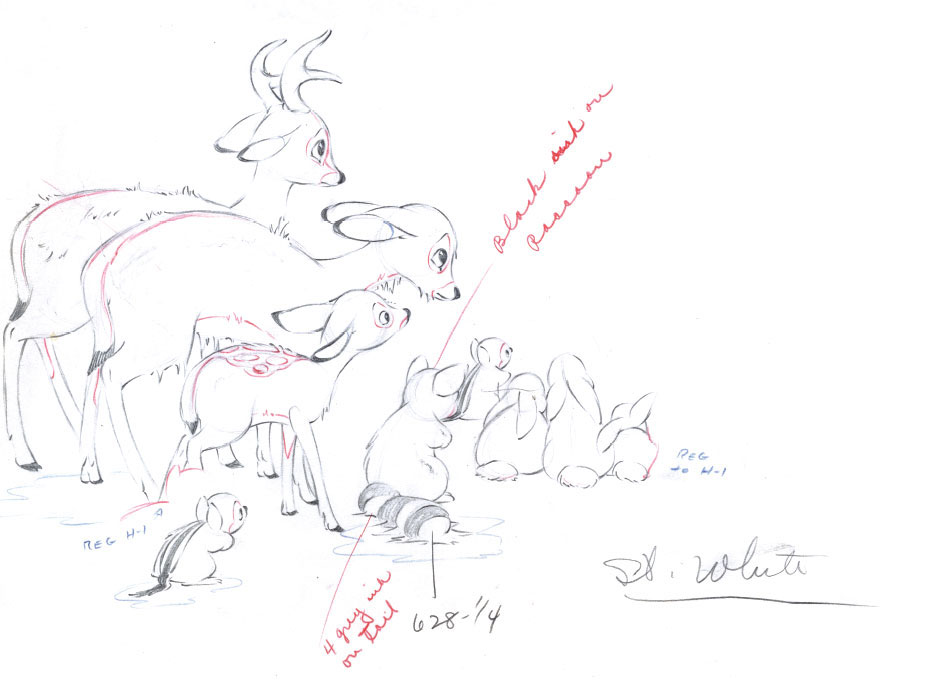

For Disney’s first full-length animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Milt Kahl teamed up with Eric Larson to choreograph the complex animation of the forest animals that interacted with Snow White. Crowd scenes like these proved technically challenging. For once, the animal groupings needed to read as a cohesive whole, but certain specific animal behaviors had to be acted out.

A dove blushes on the Prince’s hand after having delivered a kiss from Snow White.

© Disney

An emotionally charged drawing shows a group of animals mourning the death of the princess

© Disney

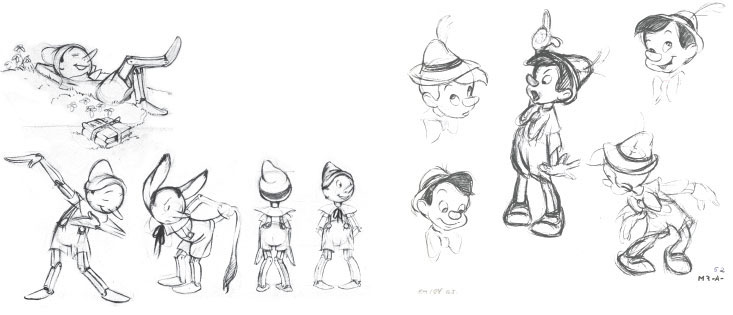

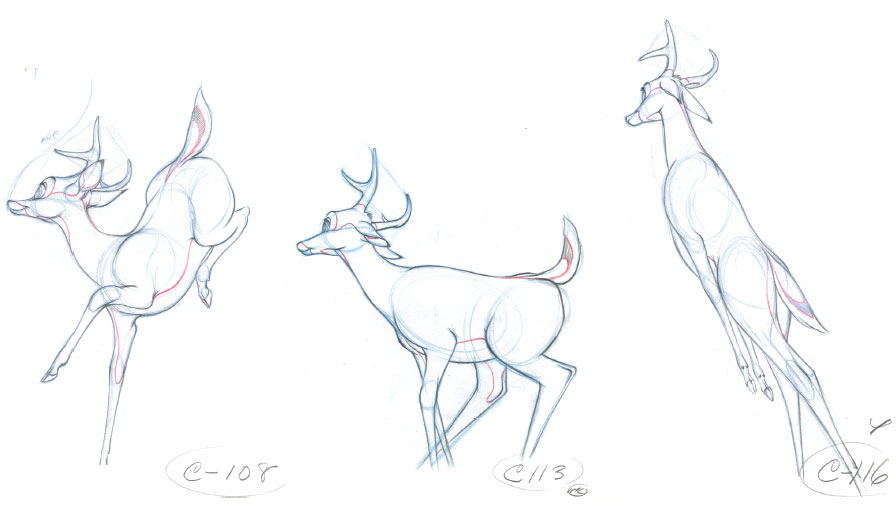

Following Pinocchio it was the film Bambi that offered new challenges for supervising animators Frank Thomas, Eric Larson, Ollie Johnston, and Milt Kahl. Walt Disney asked for believable animal characters whose anatomy needed to be based on real deer, rabbits, and birds.

Marc Davis spent many months preparing rough character model sheets showing a successful combination of animal and human characteristics. But it was Milt Kahl who shaped the final appearance for all the deer as well as Thumper, the rabbit. He went on to animate the memorable sequence, where the bunnies challenge young Bambi to leap over a fallen tree.

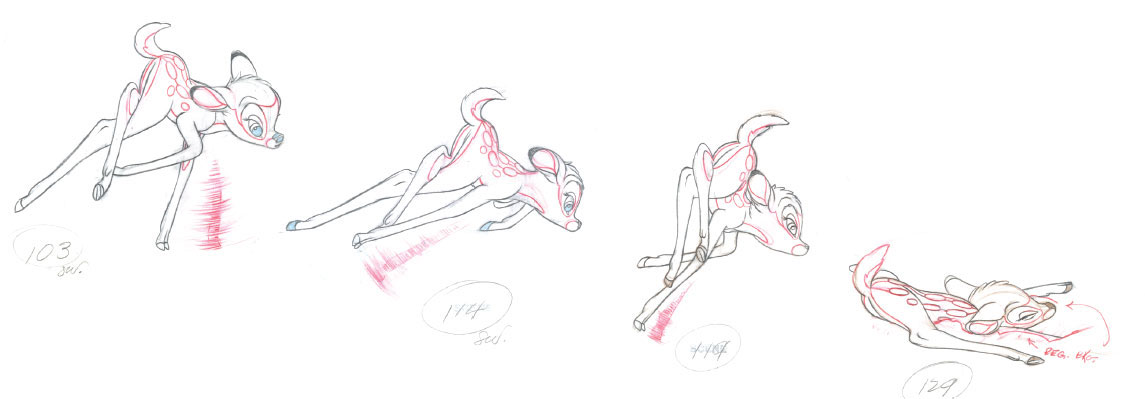

Bambi moves in very interesting and unusual ways here. His anticipation for the big jump looks like something a dog would do: head down to the ground, rear way up, tail wiggling. He then charges forward, but fails to make it across the tree. After a belly landing, Bambi moves his hind legs across the obstacle, one after the other. They interlock, and for a few moments he wobbles, out of balance on three legs, resulting in another fall. It is this carefully planned awkwardness in the animation that makes the scene so entertaining. Milt knew at any given moment about weight and momentum of all parts of the deer’s body. Because of that knowledge, he was able to play up the comedy while maintaining believability.

Milt’s knowledge about weight and momentum shines through in the sequence where Bambi is trying to jump over the fallen log.

© Disney

Milt also did most scenes with adult Bambi and Feline, including when those two fall in love. After meeting Feline as a grown-up, Bambi stumbles backward and ends up landing in water. Feline gives him a lick on the cheek and the prince of the forest is smitten. From here on the animation becomes broad and appropriately over-the-top. Bambi’s smile is so wide, it looks extreme, but fitting on a cartoon deer with such a realistic design.

A few scenes animated in slow motion follow. Bambi follows Feline, jumping elegantly through clouds—the surreal visual clues are obvious. Here again Milt shows his extraordinary talent for making impossible movements look real. After having studied realistic deer anatomy intensely, he then was able to invent unique motion patterns that looked utterly convincing.

A wide smile for a smitten Bambi.

© Disney

Bambi in love.

© Disney

During the WWII years, Disney Studios were only able to produce short-film material, but even then Milt continued to animate brilliant new characters. The 1943 movie Saludos Amigos included a section with Donald Duck and a llama in Peru. In one scene, Donald’s flute playing starts to irritate the dancing llama. The result is an example of hilariously timed comedy. The action is broadly animated, but completely believable. The llama moves always show a strong sense of weight. This is a heavy animal with a full coat of fur, and Milt makes great use of this body type. After a spirited Charleston, the llama loses control over his dance moves, a few awkward hops follow before the animal falls to the ground. During these leaps, Milt gives the llama more time when airborne and less time when making contact to the ground. (This is actually the rule of thumb when animating a four-legged animal running or jumping.) On the way up there is always a strong stretch going through the whole body, and when he finally falls down, the big squash on the llama’s rear makes for a hard impact and feels very satisfying.

Somehow Milt times these moves so beautifully, and he takes great advantage of overlapping action such as toes, the head, and all that fur. The animation is therefore fluid; it is easy to read on the screen and a joy to watch.

The dancing llama from Saludos Amigos is a joy to watch.

© Disney

For the 1943 propaganda short film Reason and Emotion, Milt Kahl contributed beautiful cartoony animation of Emotion, a caveman type, and Reason, a sort of rational bookkeeper.

Jumping from the realism of Bambi to broad character animation like this didn’t seem to be a problem for Milt at all. Even early on in his career he proved that he could handle a huge range of character concepts and animation styles.

The caveman-like character of Emotion.

© Disney

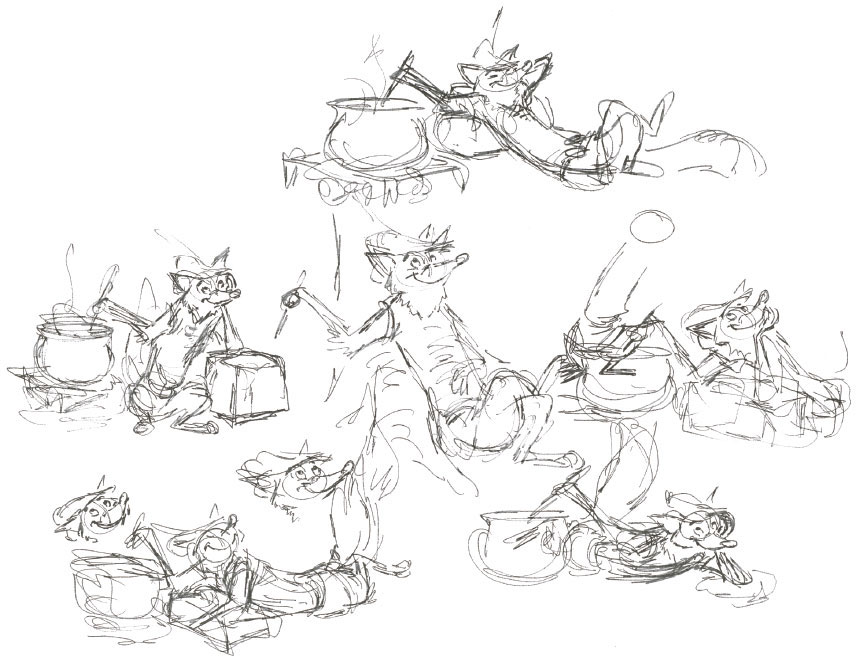

Song of the South was released in 1946, and Milt Kahl turned to story-man Bill Peet’s drawings as inspiration for the final designs of the fox, the bear, and the rabbit. Animating these characters turned out to be one of Milt’s favorite assignments. The personalities were clearly defined and very contrasting, and Peet’s story work provided the animators with outrageous situations.

These anthropomorphic animals gave Milt a chance to be much broader with his animation, something he cherished. The character’s voices provided a springboard for razorsharp timing, yet nothing looks over-animated. Key poses are held long enough to read clearly; it is the transitions to another pose that happen very fast.

These Kahl sketches show a perfect and appealing mix of human and animal traits.

© Disney

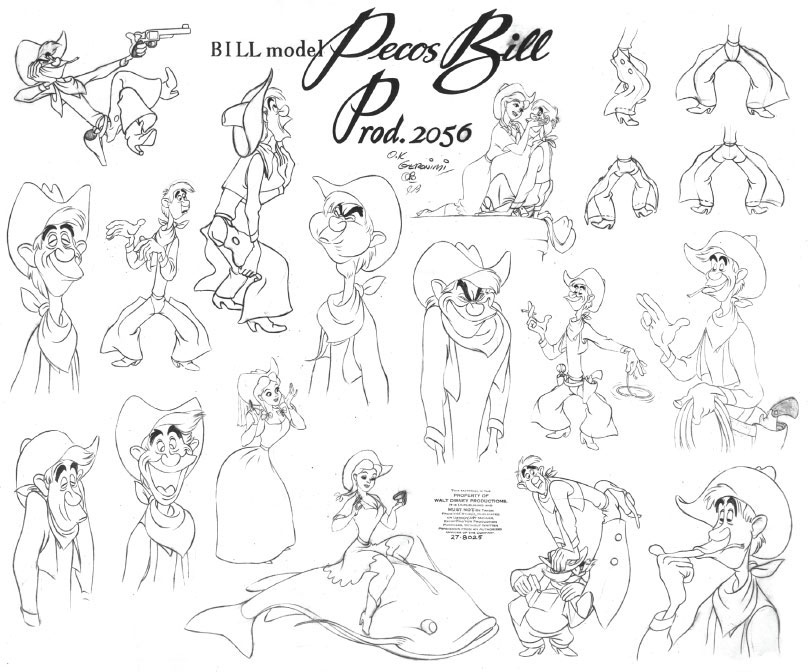

Milt animated short film characters like Pecos Bill (1948) along with Ward Kimball, then Johnny Appleseed (1948) with Ollie Johnston. The latter turned out to be a bore to animate, according to Milt. Johnny was just mild-mannered and never showed any strong emotions. Nevertheless his animation is nuanced and appealing.

A model sheet for Pecos Bill made up of Kahl animation drawings.

© Disney

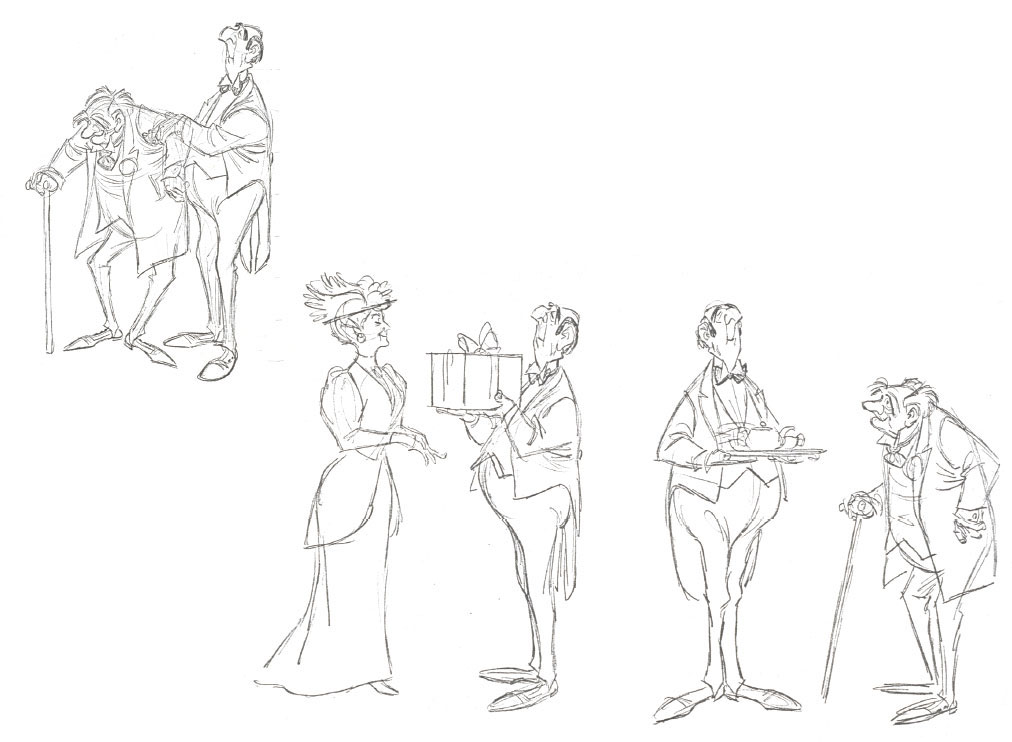

When Disney returned to full-length animated feature films, starting with Cinderella in 1950, Milt was relieved to get back to projects he felt were important. He supervised the animation of the authoritative King as well as the Duke, who is always trying to please. By now Milt had become a very experienced top animator. He was able to not only focus on good character animation, but also on the overall design of each key drawing. Clear silhouette, a balance of straight versus curved lines, and a focus on beautifully drawn hands became a standard of Kahl’s work.

The Duke from Cinderella.

© Disney

Another character he developed was the warm and sympathetic Fairy Godmother. The fact that she was occasionally absent-minded only enhanced her personality and led to interesting acting.

Milt proved that he was perfectly capable of bringing a character to life whose acting required subtleties and qualities such as compassion and tenderness. The acting is restrained until she begins to use her magic. Then the gestures become broader, and she puts real effort into creating pixie dust with her wand. “Never underestimate the benefit of props,” Milt said, and he used the magic wand to enhance the Fairy Godmother’s acting. In one scene, while in deep thought, she rests the wand’s tip on her cheek. It is a casual gesture that a grandmother might do with her knitting needle.

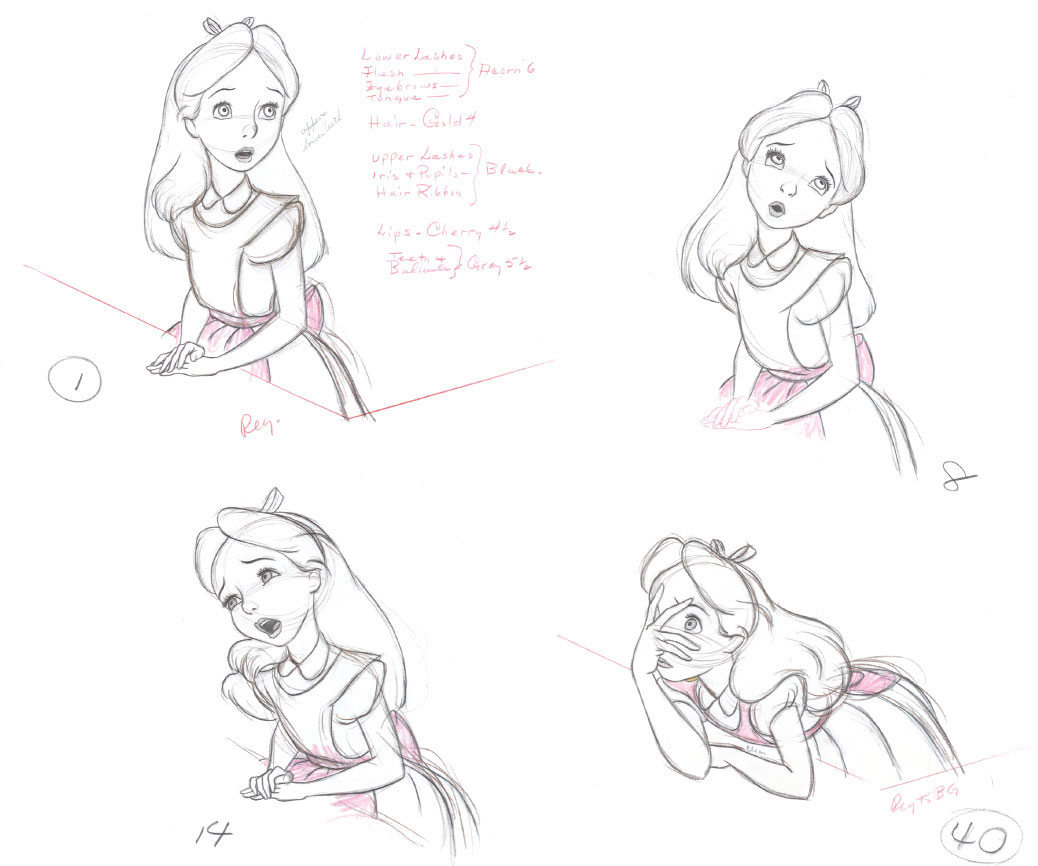

For Alice in Wonderland (1951) Milt designed and animated the title character along with Marc Davis and Ollie Johnston. Carefully based on live-action reference Milt’s animation has a simple elegance. “I don’t approve of using live action,” he stated once, “but if you deal with human characters, it is necessary.” He added that if everybody on the movie was a Milt Kahl, it wouldn’t be necessary. “But unfortunately they aren’t, so it is necessary.”

Toward the end of the film, Alice tries to defend herself during the trial. She really comes to life in these Kahl scenes because of her strong emotions. They range from anger and frustration to disbelief. During quick head-turns, the mass of her hair adds overlapping action, and the animation feels loose and real.

“Never underestimate the benefit of props.”

© Disney

Alice displays a range of emotions during her trial.

© Disney

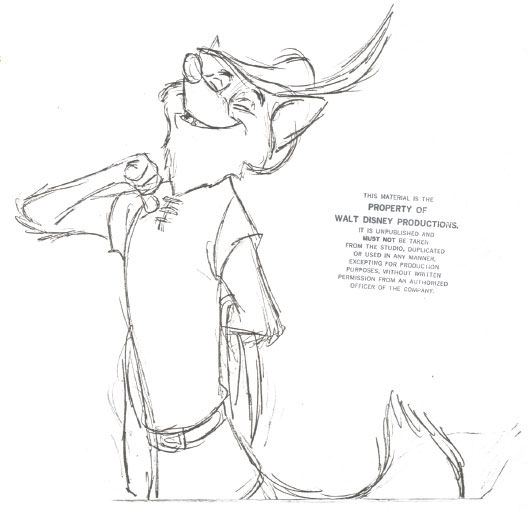

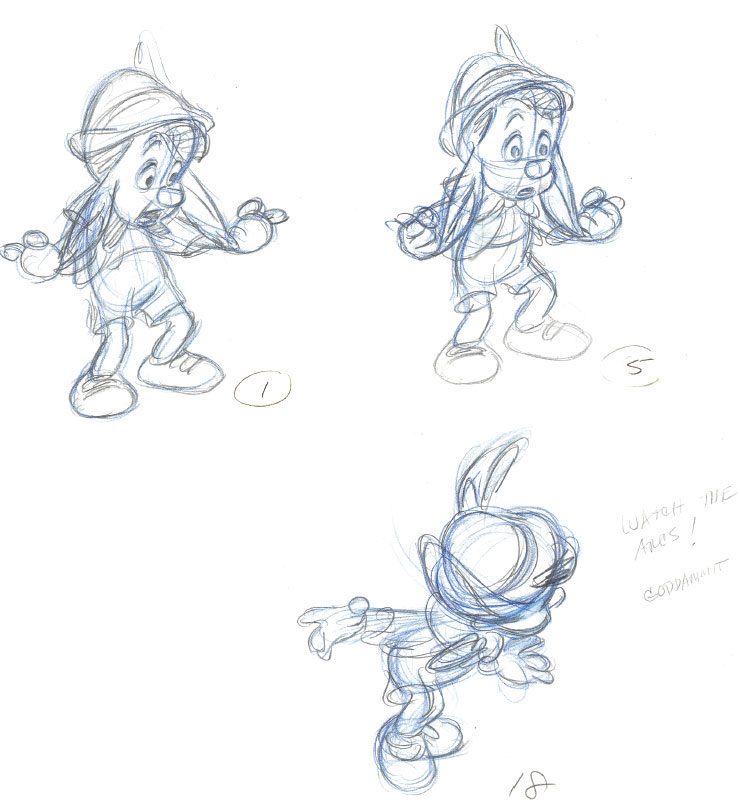

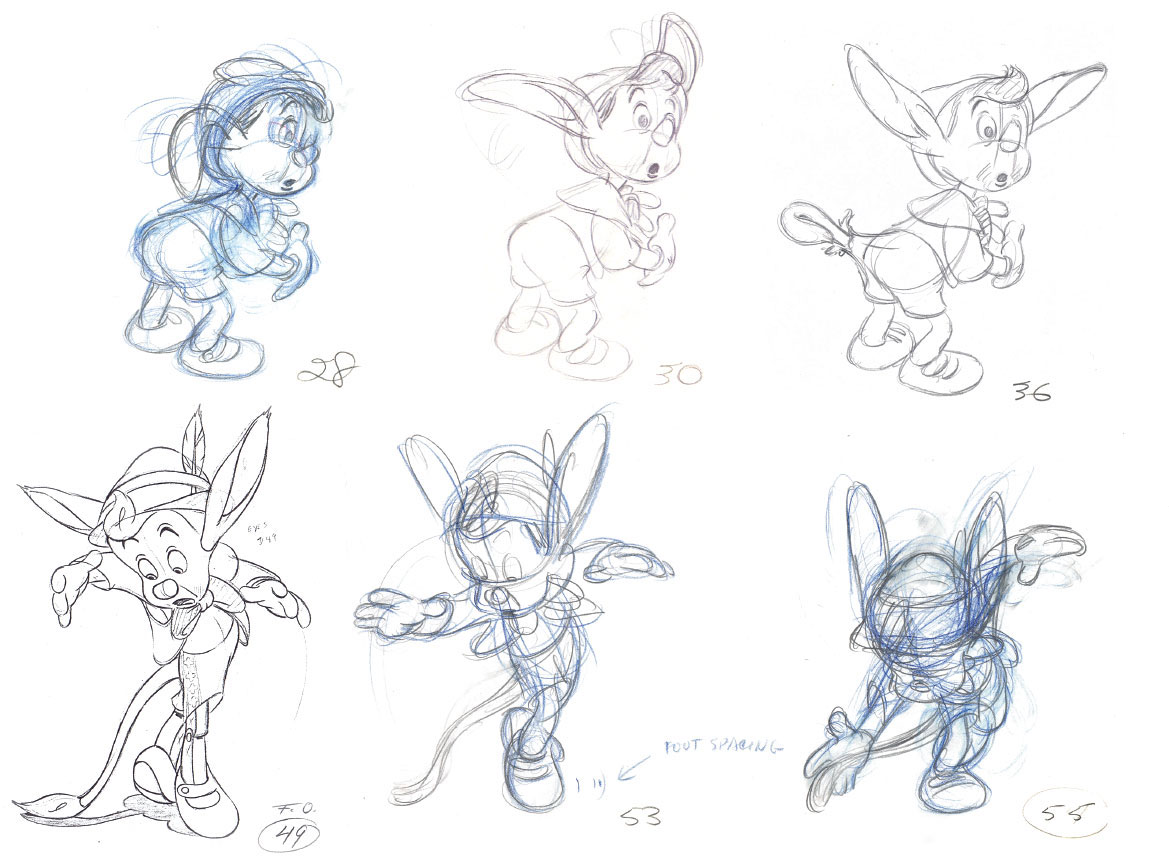

For the production of Peter Pan (1953), Milt had hoped to get assigned to the villain Captain Hook, but Walt Disney had other plans and cast him on Peter Pan and Wendy. It was around that time that Milt started to complain about having to animate the no-fun, straight characters, while his colleagues were assigned to work on much meatier roles. Ward Kimball’s response to Milt was: “Yes, but you are so good at that boring stuff!”

Animating Peter Pan was neither challenging nor very interesting according to Kahl, except for the weightless quality when he flies. For a landing, Milt usually had Peter’s upper body arrive first while his lower body catches up slowly. The result looks believable, even though the idea of a flying boy is utterly unrealistic. Peter Pan’s face is basically a caricature of Bobby Driscoll, who voiced the character. The body proportions show an age somewhere between child and young man, and only Milt drew Peter with just the right amount of realistic anatomy.

Realistic animals were once more required for the animation in Lady and the Tramp (1955). Milt designed all of the dog characters, but focused on Tramp along with Frank Thomas.

The introductory scenes of Tramp—waking up in a barrel, then stretching and taking a shower under a rain gutter—are brilliant, arguably some of the best pieces of animation Milt ever did.

Somehow the audience feels what the character is feeling. His exaggerated yawn is infectious and makes you feel tired. The drops of water falling on his head feel cold, because of Tramp’s reaction. He jumps forward, then shakes his head, chest, and rear to dry himself. It is the kind of animation that gets the viewer involved, emotionally and physically.

Early pre-animation character designs for Peter Pan.

© Disney

This early introductory scene of Tramp represents some of Milt’s best work.

© Disney

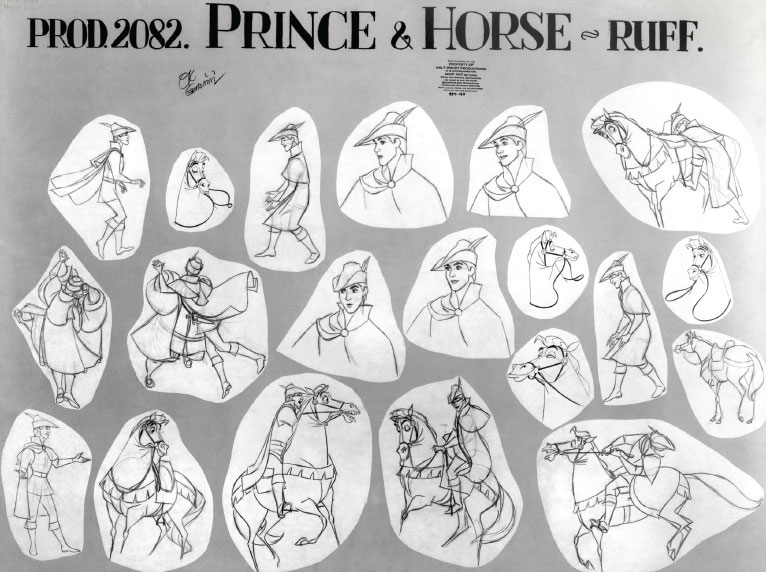

Another realistic assignment was in store for Milt when Walt Disney asked him to supervise Prince Phillip in Sleeping Beauty (1959). He did his best to bring this character to life, but pretty much despised doing it. The prince’s role in the film didn’t call for any interesting emotional changes in his acting. He was just a nice guy who falls in love with the princess; all Milt could do was to draw him in an attractive way and animate him realistically. “Not the type of animation you can get your teeth into,” he stated.

The model sheet for the prince shows subtle stylization within carefully designed poses.

© Disney

At least he had the opportunity to also animate scenes with King Stefan and King Hubert, who required a broader style of animation. The degree of caricature on these two monarchs is much greater, which allowed for broader acting and more expressive animation.

Heavyset King Hubert usually anticipates any big moves he makes, before his body mass is set in motion. Without this he would float across the screen. Skinny King Stefan is more elegant in his animation; any hand gesture is emphasized by the overlapping action of his large sleeves.

King Hubert and King Stefan provided a chance for expressive animation and contrasting attitudes.

© Disney

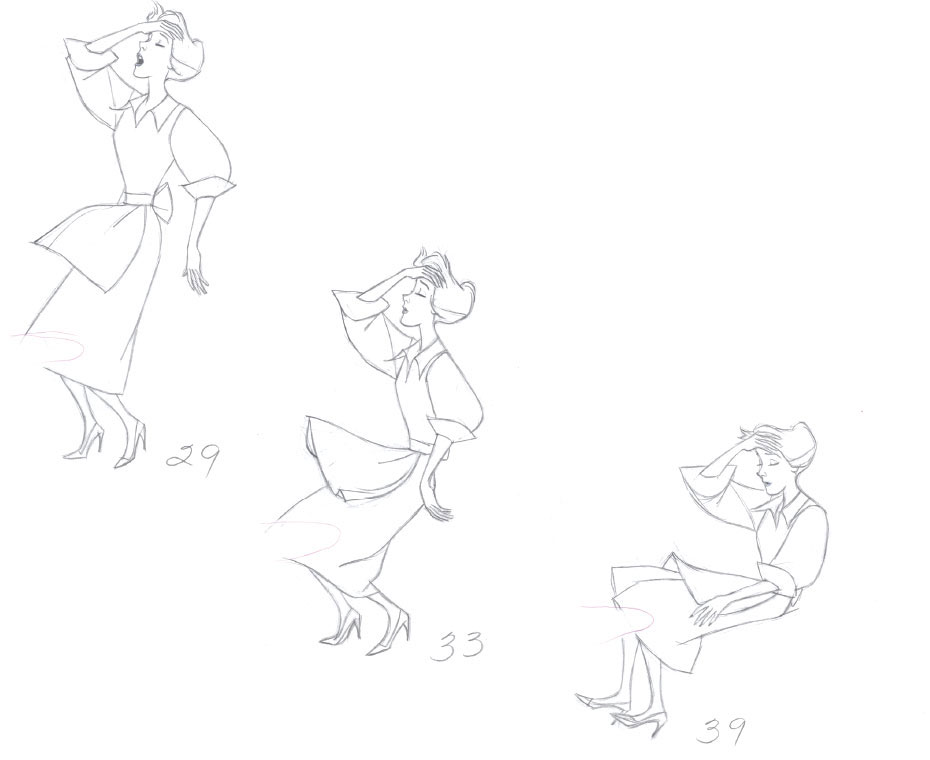

All animators were relieved when a change came about regarding Disney style. The animation drawings in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) would not be hand-inked on to cels, but for the first time would be Xeroxed instead. Milt Kahl was thrilled to see his own drawings on the screen, instead of the work of clean-up artists, who he felt often misinterpreted or ruined his original drawings. Milt animated scenes with Pongo and Perdita, but his main focus was the human couple Roger and Anita. Their animation was again based on live-action reference but because of their graphic designs, the motion feels less realistic and more interpreted. The shapes applied in their drawings often look like beautiful paper cut-outs, yet when Anita takes a seat on a couch, some of these shapes overlap in a way a real skirt or an apron would.

Although still based on live-action reference, the graphic design of Anita in One Hundred and One Dalmatians was a new direction for Milt Kahl.

© Disney

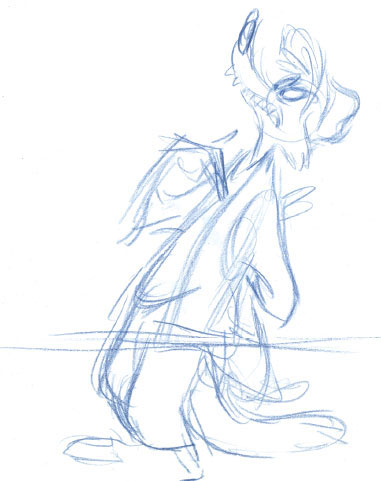

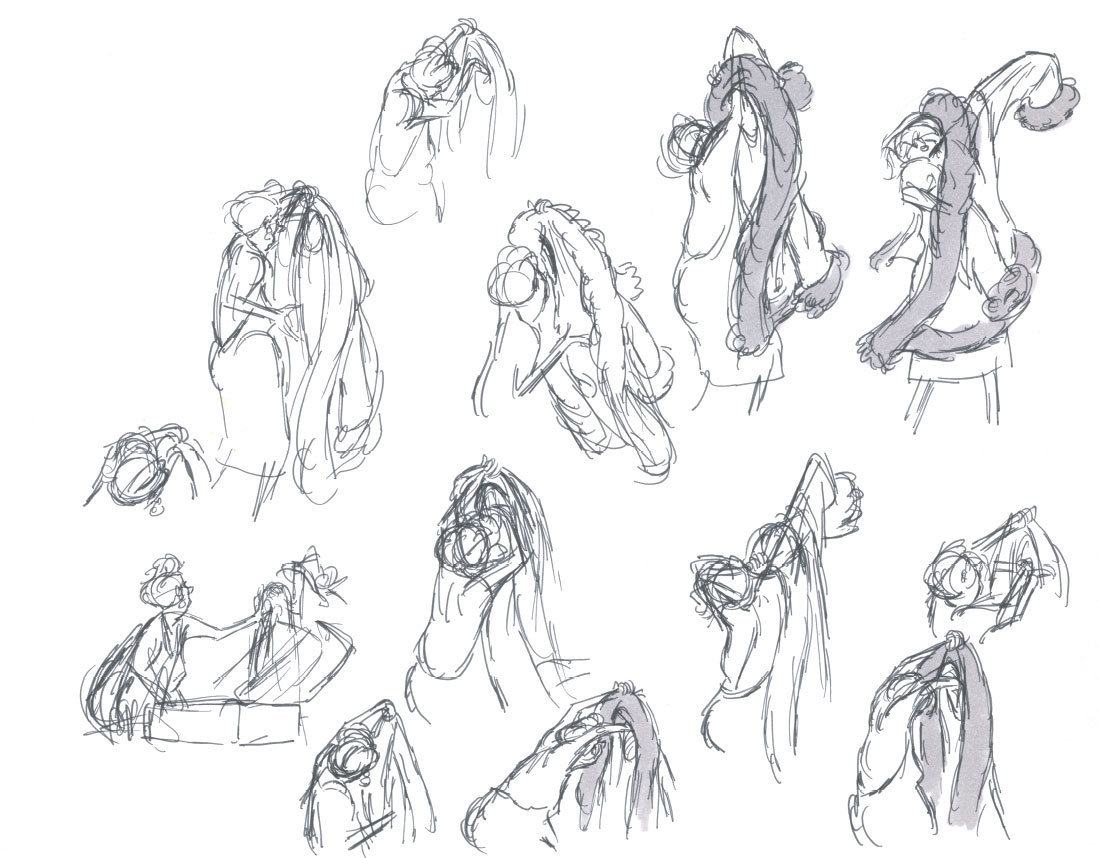

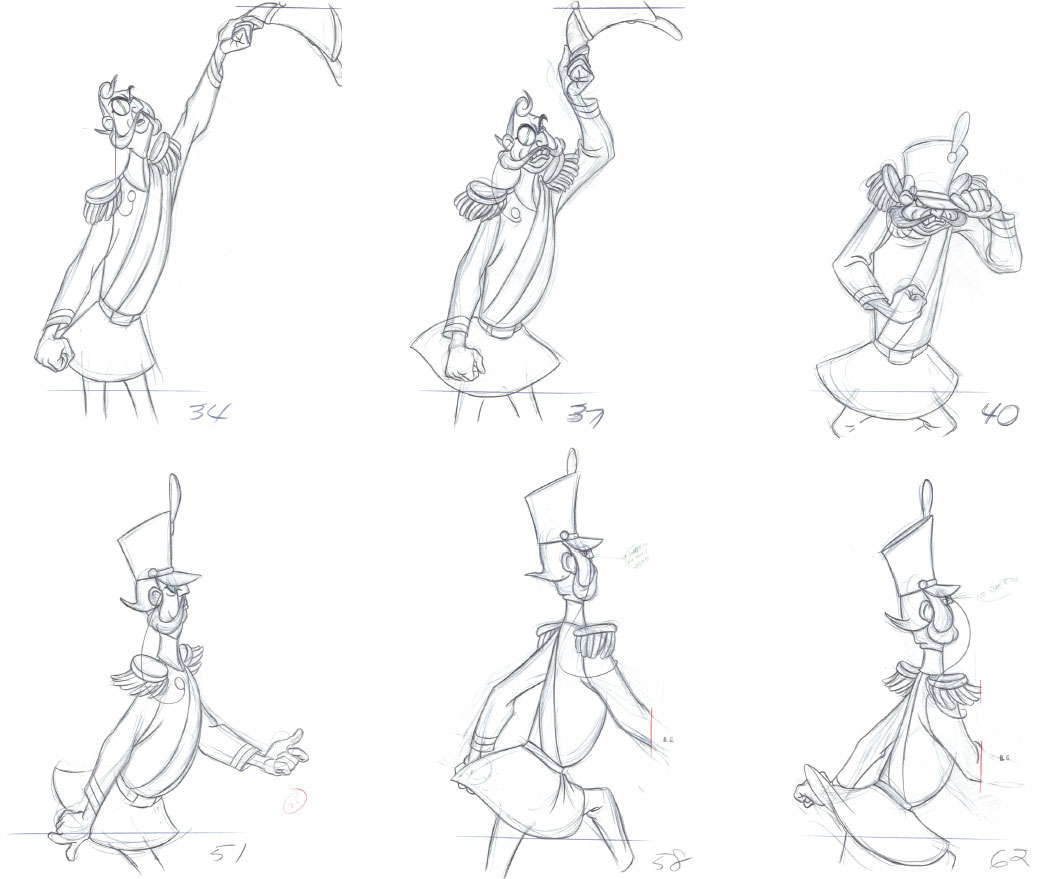

The Sword in the Stone (1963) offered many rich character parts. After setting the style for the film’s cast, Milt developed Merlin and Wart as well as Sir Kay and Sir Ector. He then shared sequences starring the comic villain Madame Mim with Frank Thomas. She turned out to be one of Milt’s favorites. A cranky, eccentric little witch gave Milt the kind of material he preferred over down-to-earth characters. When Mim introduces herself to Wart, who has been turned into a bird, she breaks into a wild and zany dance that somehow demonstrates her unpredictability.

Milt uses unusual and extreme angles during this scene, which would be difficult to draw for any other animator. Some of his colleagues would say that Milt did this just to challenge himself, others thought that Milt was just showing off his draftsmanship.

Madame Mim turned out to be one of Milt’s favorite characters.

© Disney

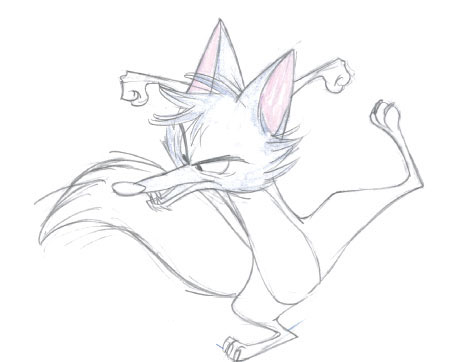

Mary Poppins (1964) required a mix of animation and live action. Milt Kahl animated the befuddled little fox, who gets saved from a pack of hunting dogs by Dick Van Dyke.

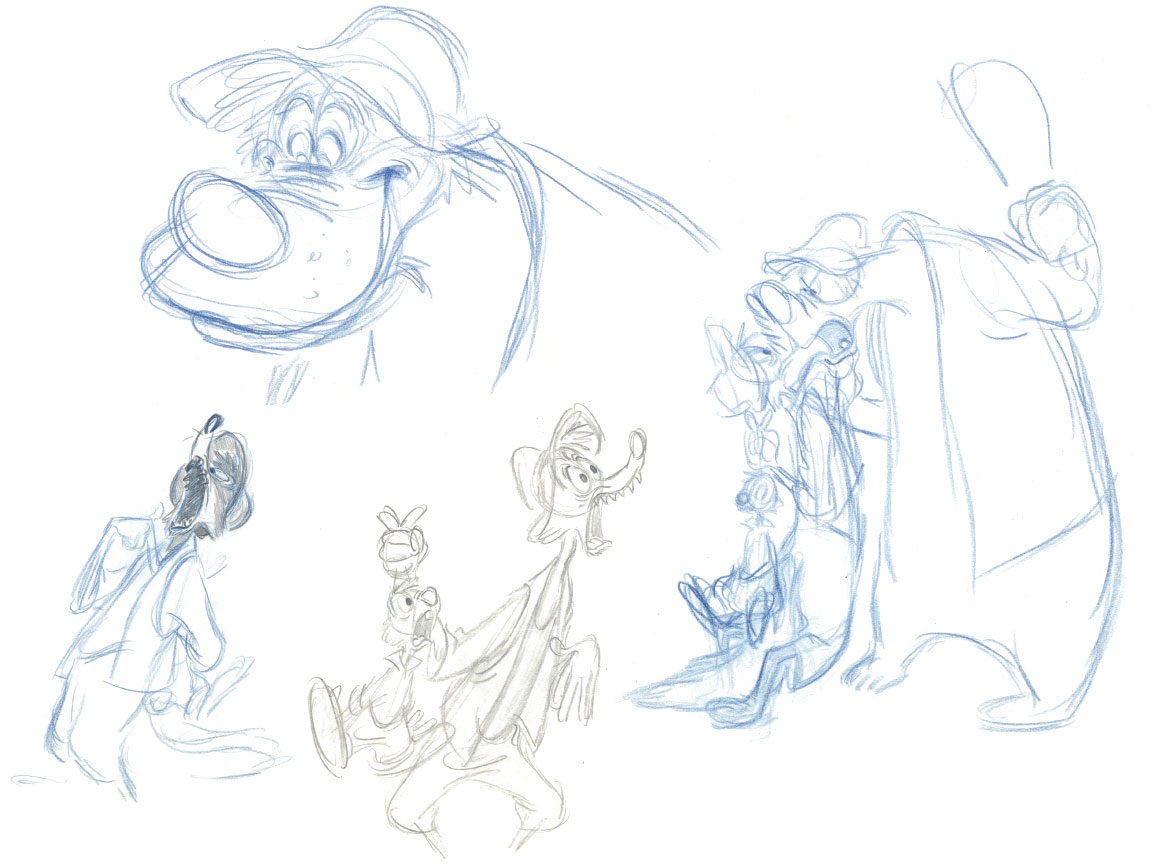

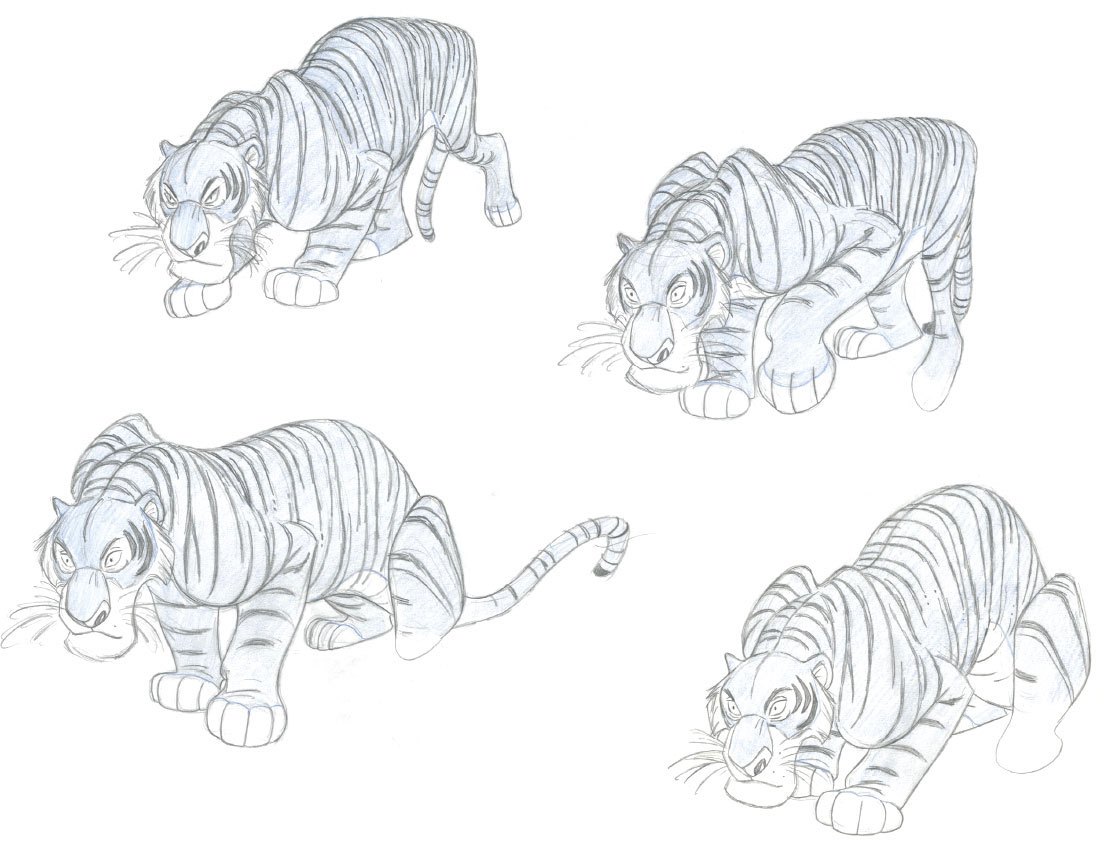

All of the characters from The Jungle Book (1967) were designed by Milt, based on sketches by Bill Peet and Ken Anderson.

Except for the elephants, Milt started out doing some animation on all of them.

But the film’s powerful villain was all his. Shere Khan is a masterpiece in design, acting, and motion.

Animation had not seen anything like this before. Almost Picasso-esque drawings moving like a real tiger. Knowingly or not, Milt Kahl made a huge personal statement here.

He started out by studying footage from previous Disney live-action movies such as Jungle Cat and A Tiger Walks. Concept artist Ken Anderson came up with the idea of a suave, above-it-all villain. Milt combined those qualities with a caricature of voice actor George Sanders. The end result is a sly tiger who is holding back his powers only to strike at the very end of the film. Stripes or spots are notoriously difficult and laborious to track on an animated animal, nevertheless they can add tremendous volume and perspective to the animated motion.

A tiger’s stripes define the exterior of the animal’s body, and in motion they emphasize different areas of its anatomy. Shere Khan moves like a real big cat—when his front feet move through during a walk, the little toe contacts the ground first before the full paw sets down. His back shoulders move up and down drastically, according to which leg is carrying the animal’s front weight. His graphic design is extraordinary. You couldn’t simplify a big cat’s body any more to its essence. Milt knew about the power of his draftsmanship, so when the tiger hits a strong pose, the drawing is held for quite some time. Only the head might move or there could be just an eye blink. Those poses and subtle moves are brilliantly composed to convey power, authority, and arrogance. The less Shere Khan moves, the more intimidating he becomes.

The fox from Mary Poppins.

© Disney

Shere Kahn is a masterpiece of subtle personality animation.

© Disney

Milt again concentrated on the human characters for The Aristocats (1970). He animated Madame Bonfamille with grace, the lawyer Georges Hautecourt with senior charm, and Edgar the butler with comic villainy.

Milt’s human characters for The Aristocats.

© Disney

This time around Milt did not refer to live-action for his animation. His opinion by then was that a top animator should know how humans and animals move and shouldn’t have to rely on live-action as a crutch. The control he exercises when animating Madame Bonfamille is astounding. Her walk has just the right amount of delicate bounce and feels very natural. The old lawyer shows his age with a knee wobble for each step, but the overall acting is quite energetic since he is still young at heart. The butler’s expressions are at times very broad. When he finds out that the cats are to inherit Madame’s fortune, his frustration is severe. He mutters “Cats!” and Milt involves the whole face when pronouncing the word. First the mouth opens extremely wide, then closes while eyes and eyebrows form a strong squint.

“Cats!

© Disney

There are a few memorable moments in the animated sections of Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971). Milt didn’t work on the famous soccer game (except for designing the players), but he was responsible for developing the tumultuous relationship between King Leonidas and his assistant, the Secretary Bird.

King Leonidas interacts with his long-suffering assistant.

© Disney

Ken Anderson provided many sketches before animation for Robin Hood (1973) began.

Again Milt Kahl polished and finalized them. He animated key scenes with Robin, Maid Marian, Lady Kluck, and Friar Tuck as well as the rooster Allan-a-Dale and the Sheriff of Nottingham.

Robin Hood as a fox is a very different animal than Brer Fox from Song of the South. For once, the Disney style had changed from dimensionally drawn, often cartoony characters to designs that were influenced by modern graphics, and Milt Kahl had more to do with this trend than most artists at the studio. But the acting had changed, too. These animals often demonstrate nuanced, human behavior and the acting is much more subtle than in earlier Disney films.

Brer Fox from 1946.

© Disney

Robin Hood from 1973.

© Disney

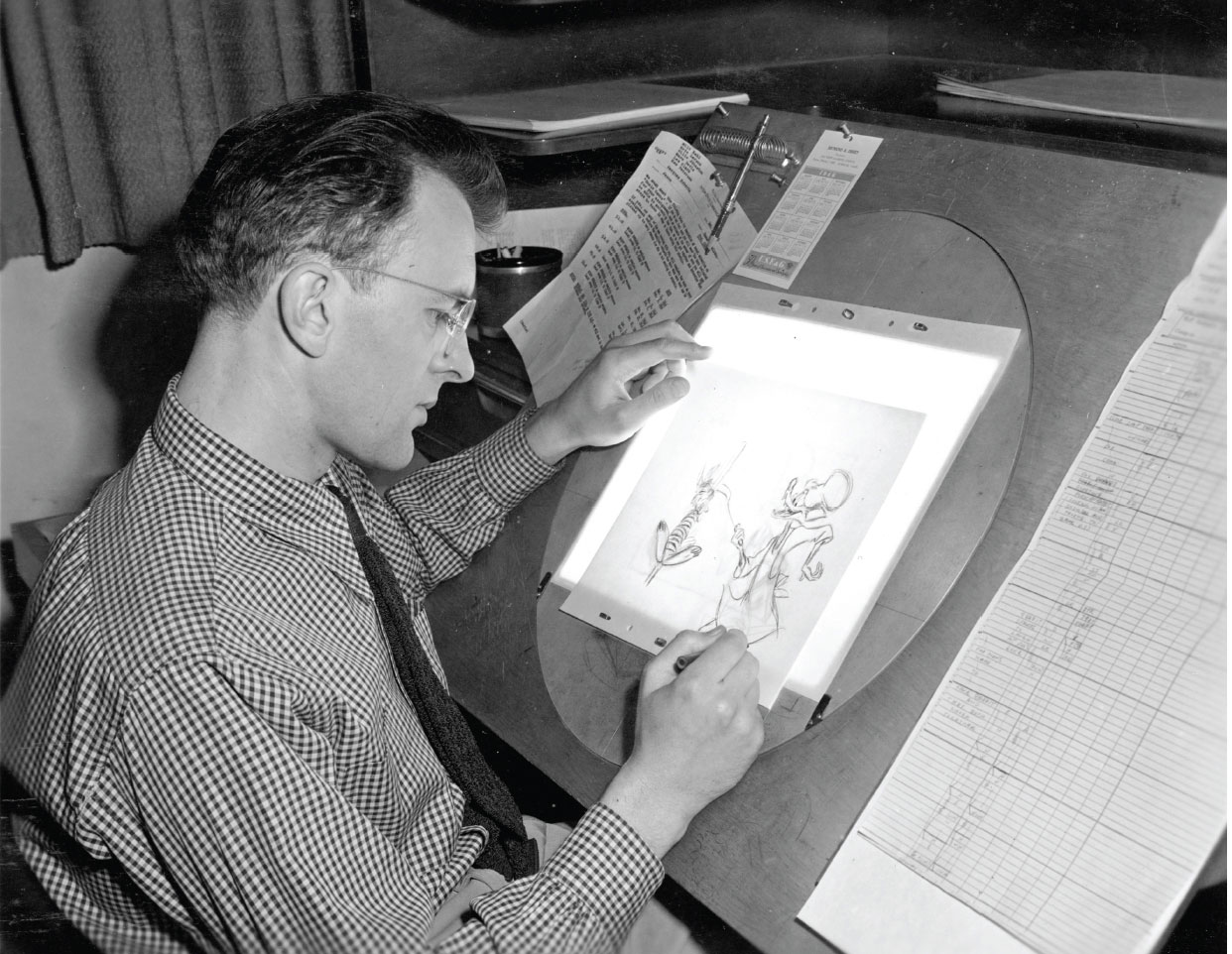

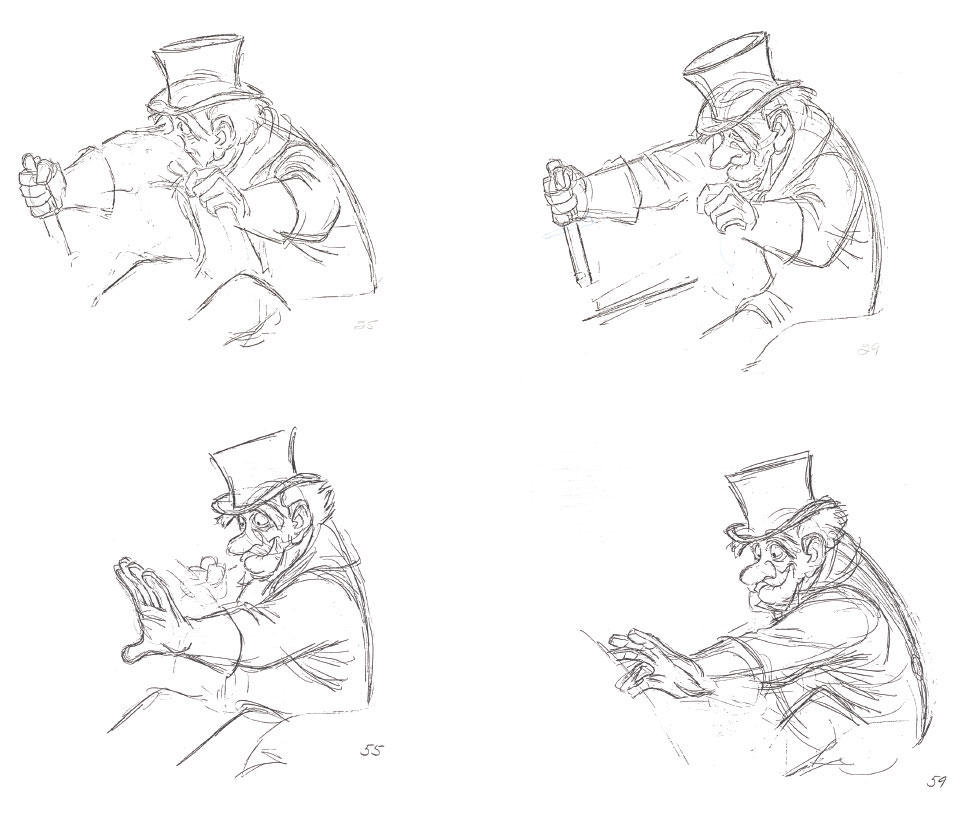

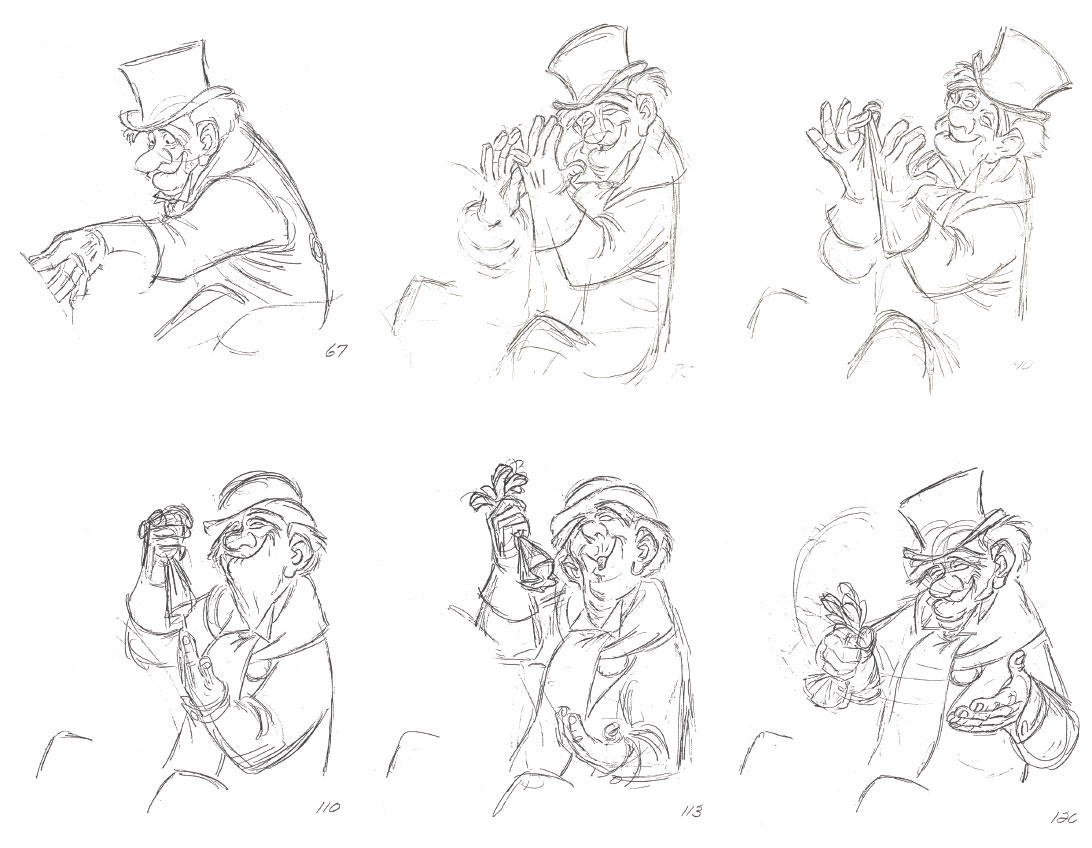

Milt Kahl’s work method always included precise planning. Before animating, Milt spent a lot of time exploring all possibilities for a scene. He often would stare at a blank sheet of paper for a long time before coming up with small pen or pencil sketches that helped him analyze various ideas for poses and acting patterns. Milt insisted that you need to think about where you are going with the scene before animation begins.

Figuring out ideas for poses and acting patterns.

© Disney

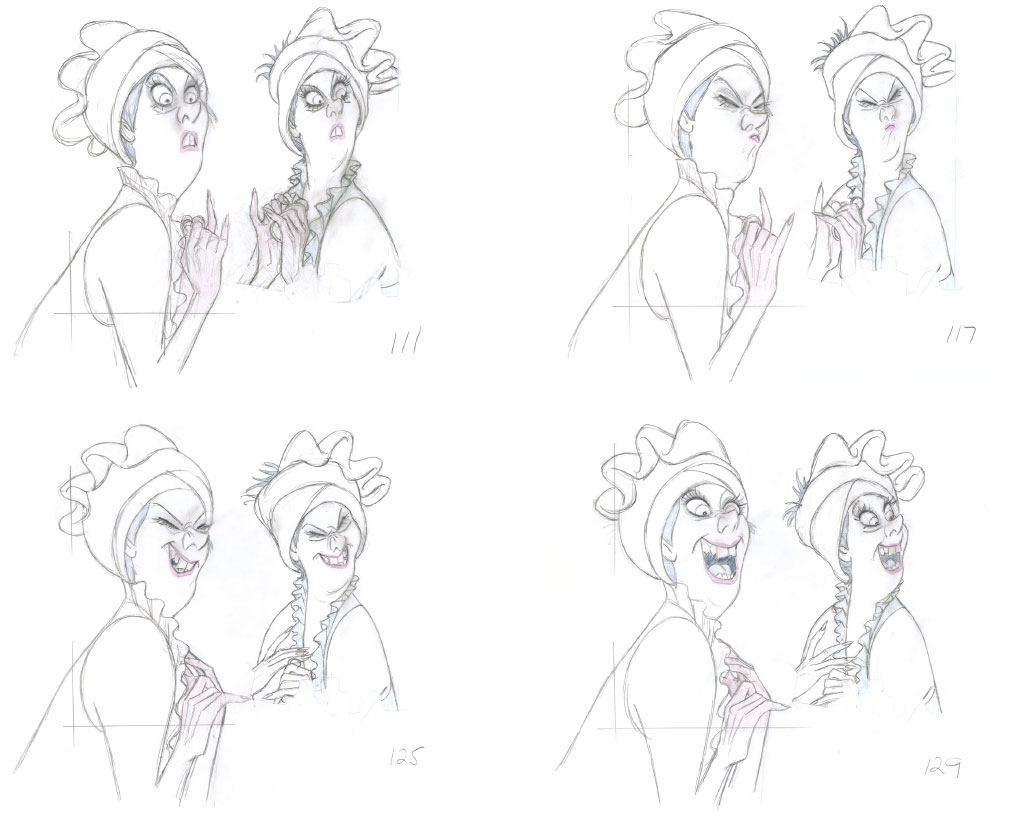

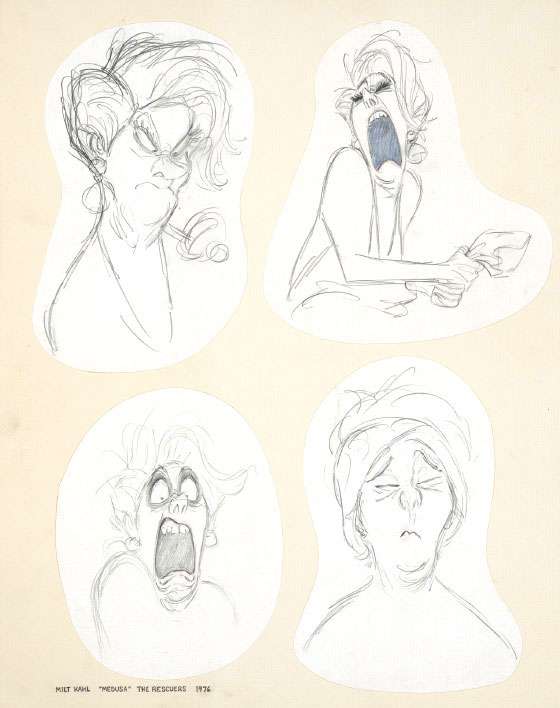

For his final assignment at Disney, Milt took on the villainess Madame Medusa in The Rescuers (1977). Being very inspired by Geraldine Page’s voice performance, Milt pulled all the stops. He would later say that he probably had more fun animating her than any other character before. Medusa is an animated force to be reckoned with—wildly eccentric while enormously entertaining to watch. No live-action reference was used, her motion is a total creation of the animator. Milt also animated her partner in crime, Mr. Snoops, as well as establishing scenes with the alligators Nero and Brutus. Medusa’s design is so unique and individual that only Milt Kahl could draw her. Broad, round shoulders contrast lower arms that look like sticks.

Her soft, flabby body allows for a great range of unusual poses. The expressions Milt invented for her are repulsive and wonderful at the same time.

It is interesting to note that Milt animated most of his acting close-up scenes on “twos,” which meant that only 12 drawings per second are seen on the screen, instead of 24. That kind of motion tends to look a little less fluid, but it sure has a crisp snap to it. He also used a mix of ones and twos, depending on what kind of feel a particular motion should have.

Milt Kahl left Disney Studios somewhat prematurely. He was still in top form artistically, but his outspoken, critical point of view on the status of Disney animation was met with resentment and frustration by other artists and management.

Nevertheless he left behind an unparalleled animation legacy of an extremely high standard, which is still admired and studied by fans and professionals today. His drawing style dominated Disney animated films for 40 years and his drive for perfection is inspirational and intimidating at the same time. There is no doubt that the work of Milt Kahl will inspire artists for generations to come.

Medusa is an animated force to be reckoned with—wildly eccentric while enormously entertaining to watch.

© Disney

1940

PINOCCHIO

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 8.5, Sc.24

The story of Pinocchio takes a dark turn when the title character suddenly realizes that little by little he is turning into a donkey. He had just watched in horror as the boy Lampwick went through the same transformation.

Milt animates Pinocchio turning left and right to show his confusion, ending up in a pose with his back to the camera. At that point the character holds very still, when all of a sudden a tail appears. That isolated piece of action reads very clearly because the tail is the only thing moving at this moment. In realizing his escalating physical change, Pinocchio’s body stretches upward. Milt uses this pose in anticipation for the down motion during which Pinocchio grabs the tail and holds it in disbelief.

From a technical point of view, this is a very well-choreographed scene with short pauses, just long enough to show the character’s emotion. The audience is left with a feeling of anxiety and suspense.

© Disney

© Disney

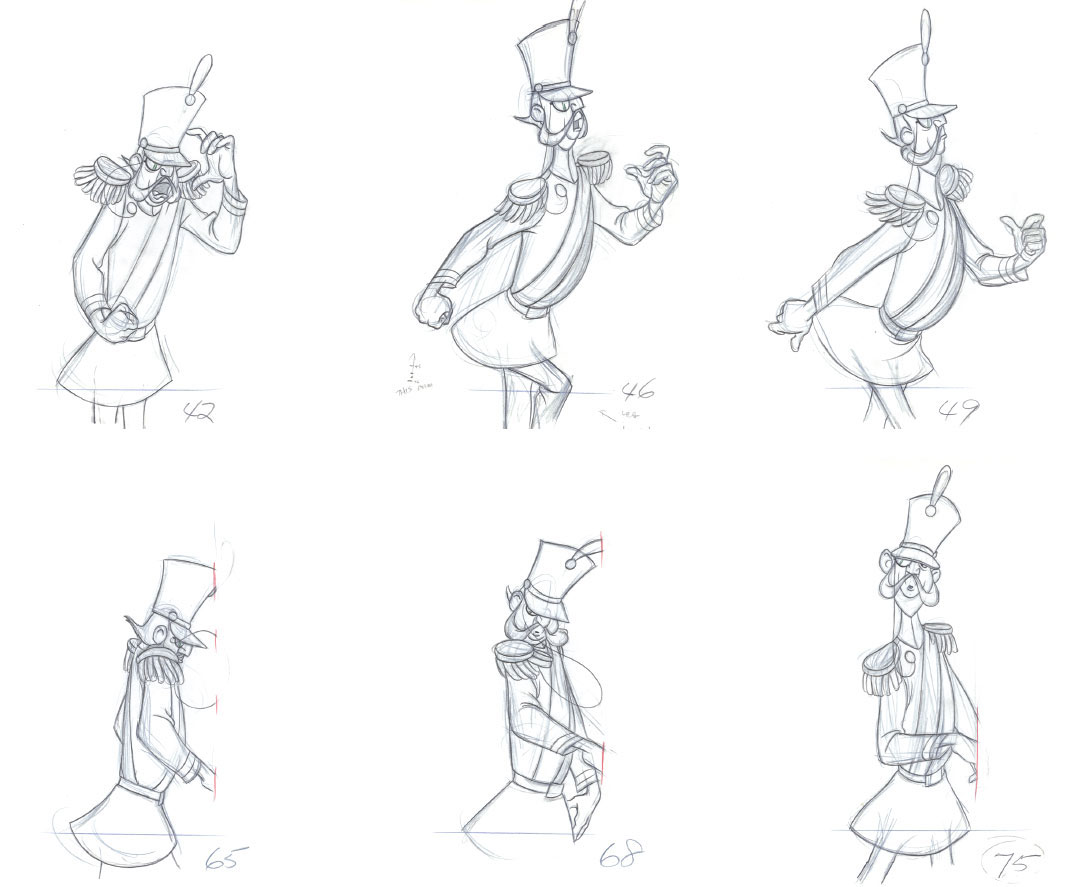

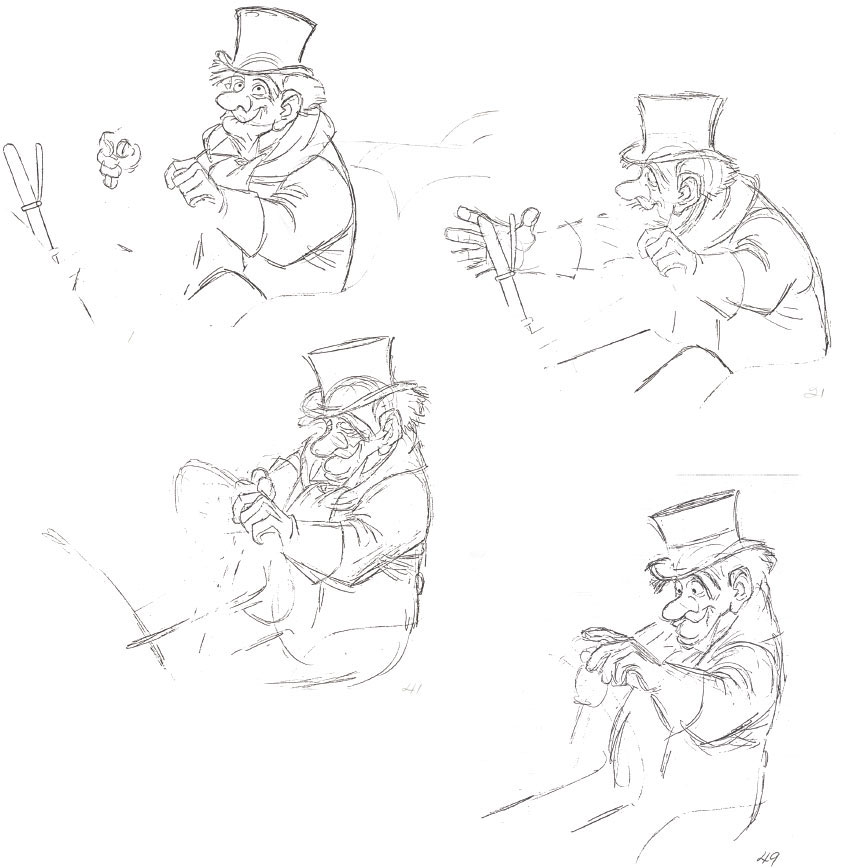

1950

THE GRAND DUKE

ROUGH AND CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 5.1, Sc. 193

The Grand Duke is about to leave the home of Lady Tremaine after being informed that no other girl beside Drizella and Anastasia, who did not fit the glass slipper, lives in the house. He turns towards the door while putting on his hat. Suddenly from upstairs a voice appears: “Your grace…” The Duke stops and looks over his shoulder in the direction of the voice.

This is a short scene, but full of personality. It shows Milt Kahl’s ability to portray emotions during a brief moment, which otherwise might be considered a second rate continuity scene, a scene of lesser importance.

The Duke’s motion and dialogue “Good day… good DAY!” signals that he has had enough of these ladies. The slipper didn’t fit, he has wasted his time, and is eager to move to the next house in search of the mystery girl from the ball.

Milt draws a theatrical pose, as the character lifts his hat up high, before putting it firmly on his head. His march-like walk shows determination and annoyance. It offers a nice contrast to the abrupt stop that follows.

© Disney

© Disney

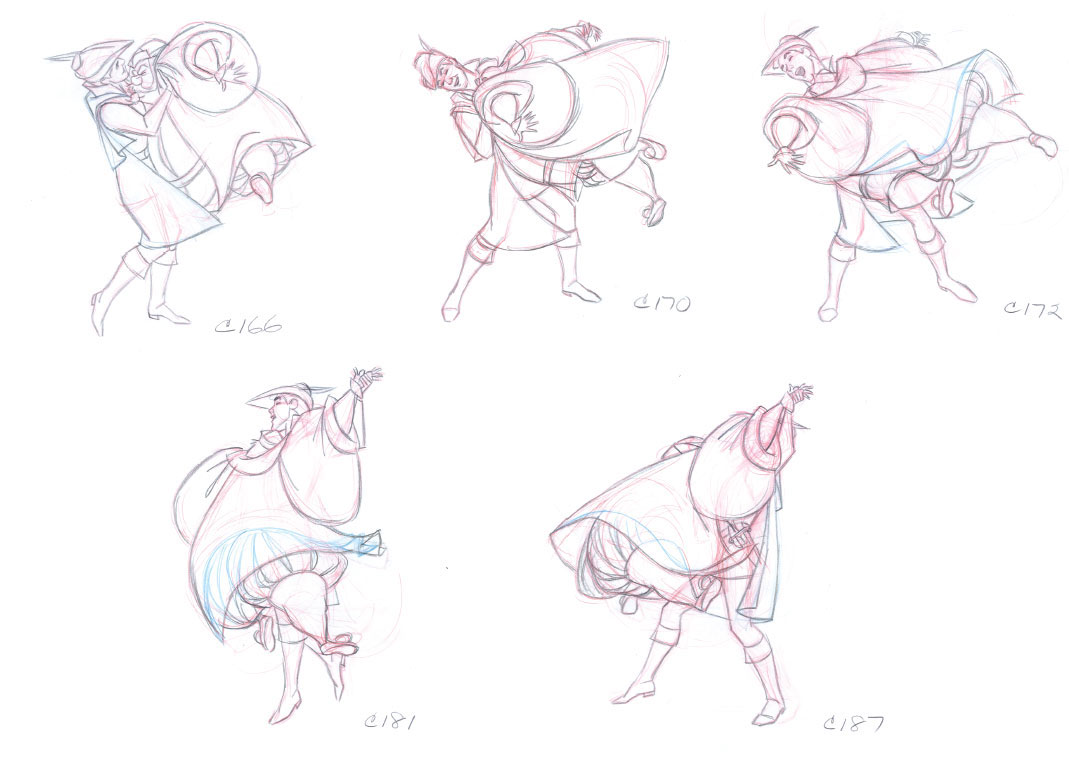

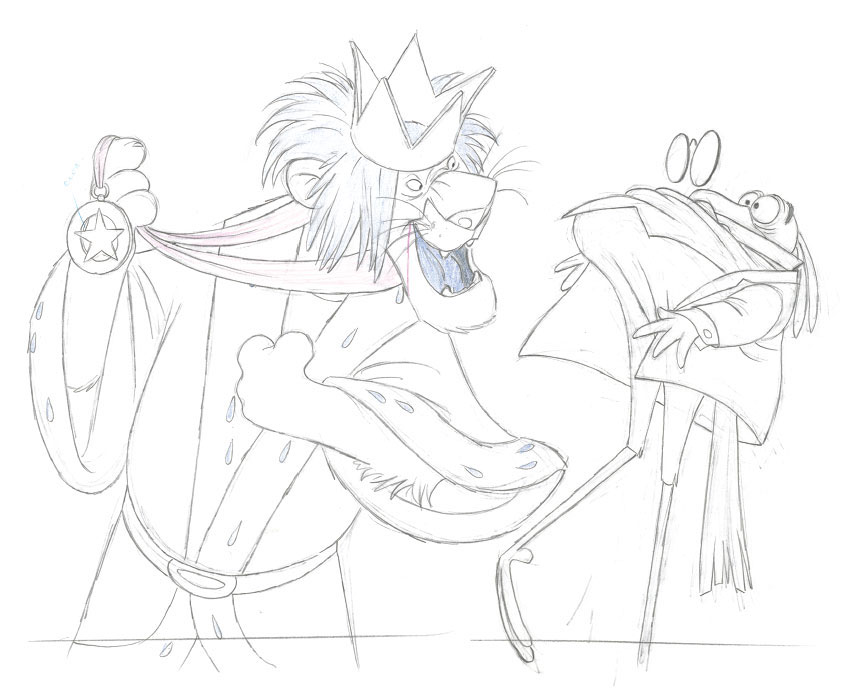

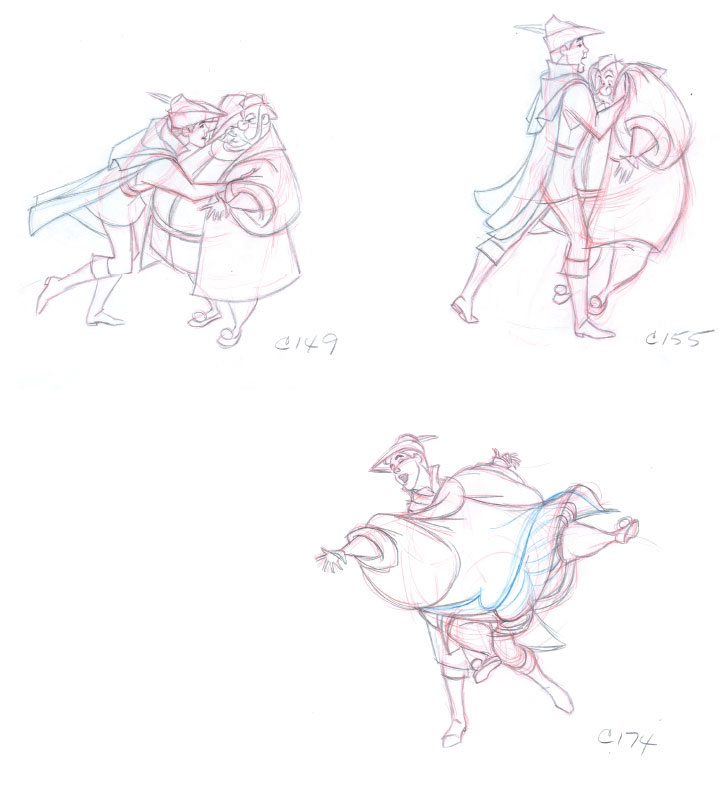

1959

KING HUBERT AND PRINCE PHILLIP

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 13, Sc. 52

This scene shows Prince Phillip as a character who is capable of projecting strong, even silly emotions. He just told his father, King Hubert, that he met the girl he is going to marry. Phillip then picks up the bewildered king and swirls around in a waltz-like fashion. Technically the scene is a tour de force, which required accurate analysis of the footwork involved in this type of dance.

© Disney

The way Phillip leans into the action demonstrates his elation as well as playfulness.

Animated without the help of live-action reference, Milt demonstrates his skills for musically choreographed motion. At the time, the scene was met with some criticism by colleagues who questioned the believability of a regularly built person being able to lift up such a heavy character as Hubert.

But the empowering feeling of love enables this animated prince to do the impossible, and to most audiences the scene looked entirely plausible.

It is interesting to see how Hubert’s coat was shortened with blue pencil, most likely to enhance the comedy by showing more of his puffy underpants.

© Disney

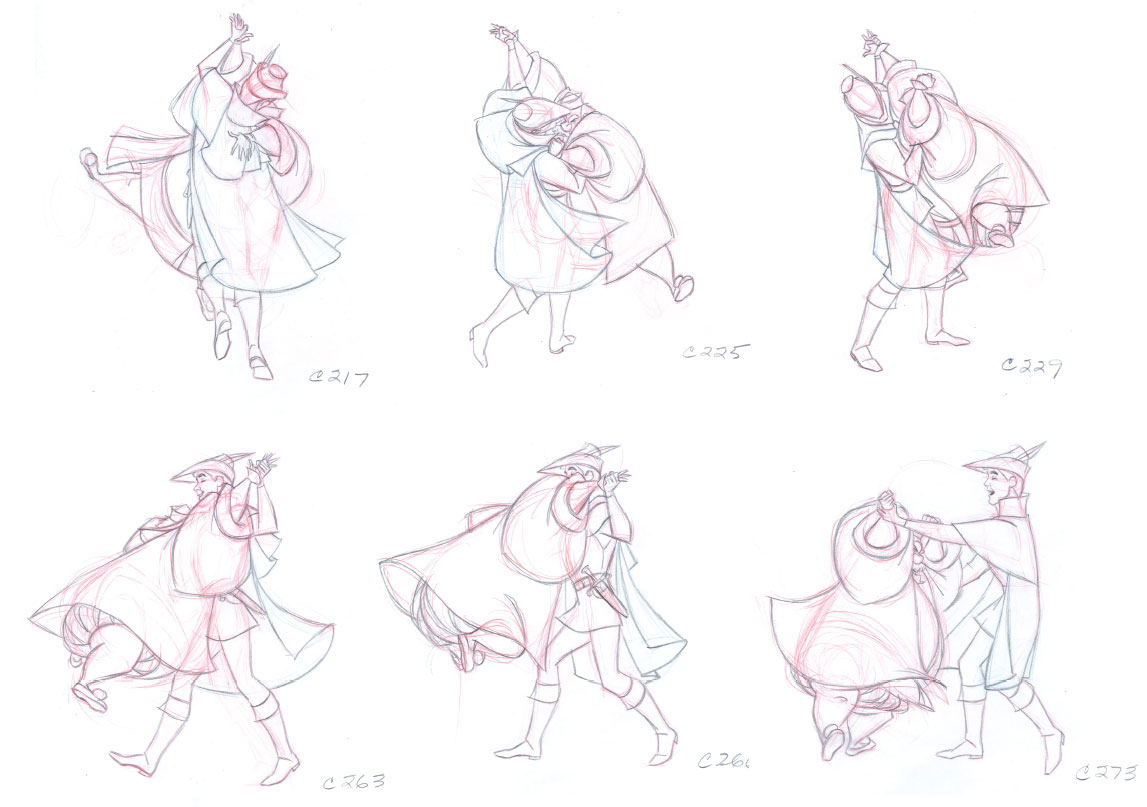

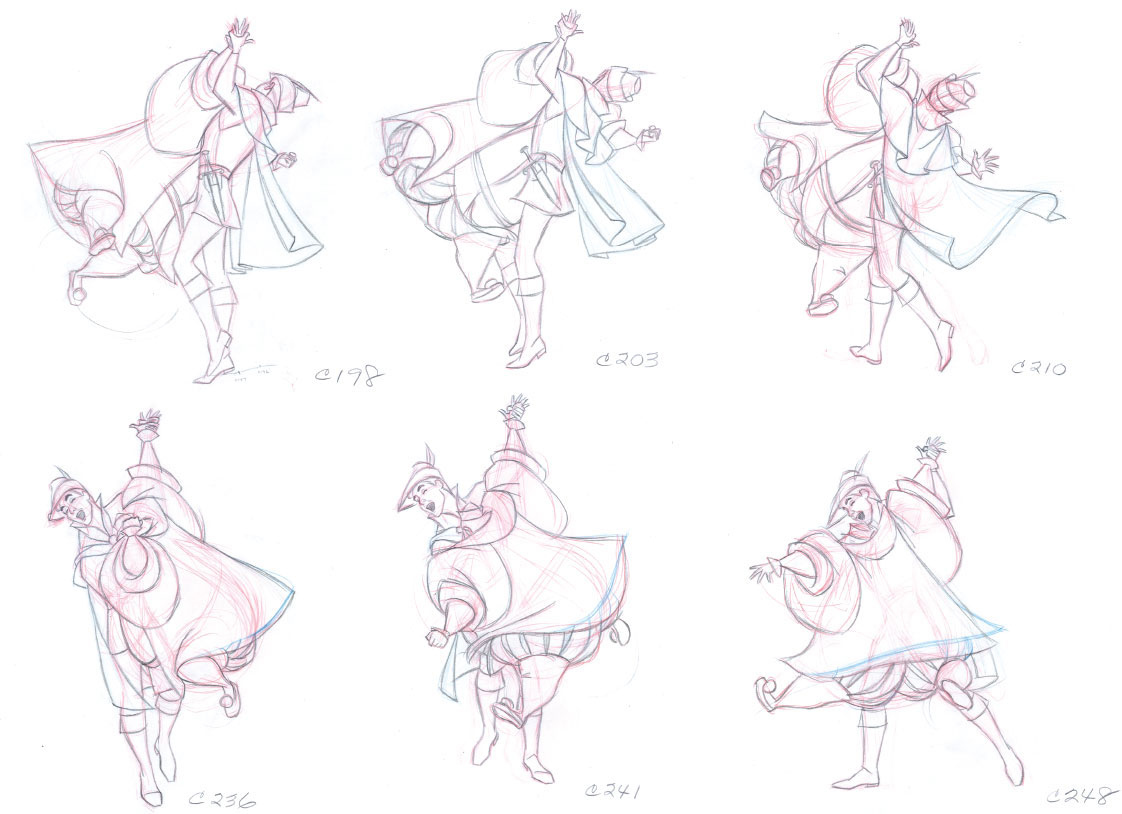

1970

GEORGES HAUTECOURT

ROUGH ANIMATION

Seq. 4, Sc. 1.1

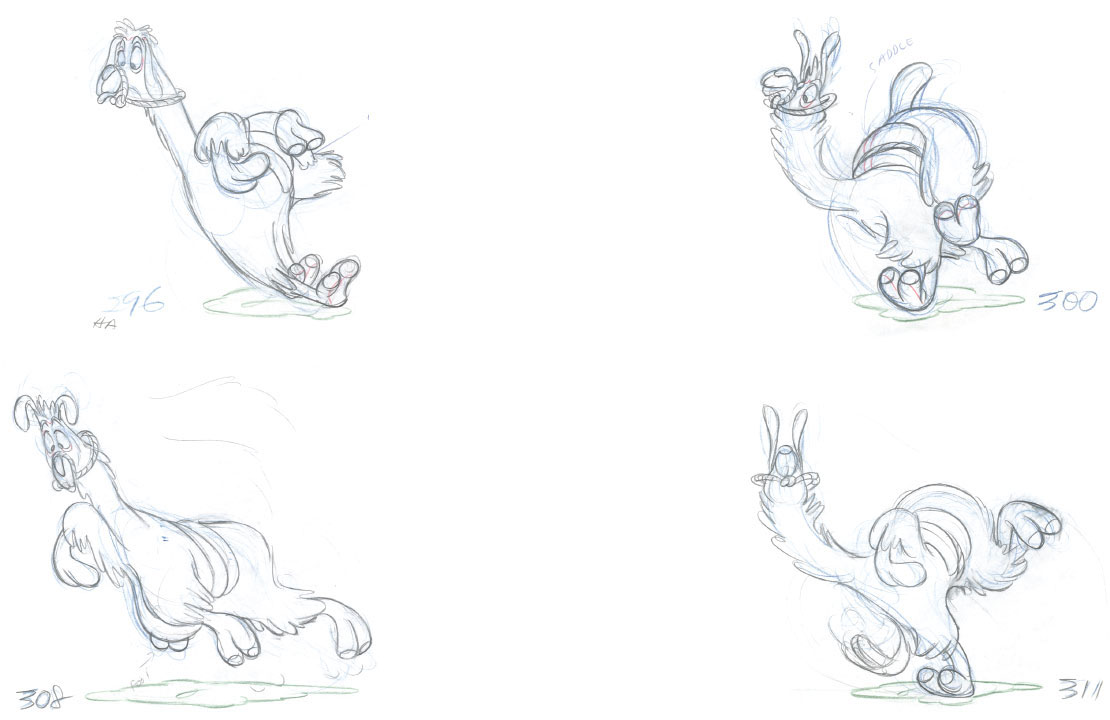

The introduction of Madame Bonfamille’s lawyer Georges Hautecourt is pure delight. He might look like he is 100 years old, but his spirit is youthful and energetic.

After he arrives in his car in front of Madame’s house, the lawyer turns off the engine and removes his gloves in rhythm to the tune he is humming. Motionwise, there is a lot going on at the same time, yet everything reads beautifully as a whole. Hautecourt’s head is tilting from side to side as he sings along, while each finger is loosened before a glove is removed. The squash and stretch involved gives the gloves the appearance of soft leather. The same can be said about his face which is full of squishy wrinkles.

The hands’ movements are drawn with masterful precision, and the overall bounciness of this performance reveals the character’s optimistic personality. He is in a joyful mood and ready to tackle any legal issue coming his way.

© Disney

© Disney

1977

MADAME MEDUSA

ROUGH/CLEAN-UP ANIMATION

Seq. 7, Sc. 300

Medusa just sat down in front of a mirror to remove her make up. She is irritated and furious because the kidnapped girl Penny hasn’t been able to find a big diamond for her, called the Devil’s Eye. Medusa removes her earrings when she is interrupted by Penny at the door. She immediately changes her attitude from anger to false delight. “Come in, come i-hin!”

Often when there is a strong change in a character’s mood, the animator would close the eyes, before opening them with a new expression. This method is a standard for an emotional transition.

For Milt Kahl this approach wasn’t good enough. During Medusa’s quick mental change he added a couple of deliciously bizarre expressions that still communicate a spiteful annoyance. The audience doesn’t fully register these grimaces at the speed of 24 frames per second, but rather feels the character’s madness.

As soon as she addresses the girl, Medusa’s attitude is completely fake and acted out.

© Disney