When You Are Really, Really Wrong

We’ve talked about those myths perpetuated by investors inventing or imagining causal correlations where none exist. What about those myths so wrong the inverse is actually true? Sometimes, when you ask Question One, you discover you have been not only wrong but really, really wrong. Don’t fret. Discovering you have been wrong and uncovering a reverse truth gives you yet another basis for a market bet. A powerful one because you know for certain everyone is betting on the exact opposite of what you know is likely to happen.

It may be hard for you to imagine something you and your fellow investors can get so completely wrong. But there are some myths in the misguided investor doctrine held so dearly, questioning them is almost sacrilegious. Suggesting such a belief be scrutinized, if only to confirm its veracity, would bring outrage, scandal and possible excommunication. These myths, the most sacrosanct beliefs in the investor and social catechism, those no one dares question, are sometimes ones we find to be so wrong the exact opposite holds true.

The Holiest of Holies—the Federal Budget Deficit Myth

You probably believe a high federal budget deficit is bad. Everybody knows budget deficits are bad. How do we know? We know because everyone knows. Duh! Pundits, politicians, patriots, perverts, poker partners, your parents, your pet parakeet and worst of all, Sean Penn, Brad Pitt and Dolly Parton. Everyone! More important, everyone believes it. There is absolutely no reason to question this belief. I mean, how do you question Sean Penn and Brad Pitt? Which makes this sacredly held myth a great candidate for Question One. What do you believe that is wrong? Better yet, reframe and flip it on its head and ask yourself the reverse.

Is a high federal budget deficit good—and good for stocks?

Ask that question too loudly and someone may come after you with a butterfly net and commit you to a nice, safe, padded cell. Believing a budget deficit is bad is part of our collective Western-world wisdom and culture—nay, our civic duty. As stated earlier, deficit has the same Latin root as deficient. Why question something believed for thousands of years? Because it’s wrong!

We are taught as children to regard debt as bad, more debt as worse and a lot of debt as downright immoral. Right after we finished making paper turkeys for Thanksgiving, we got a cookie, some apple juice, a lecture on the immorality of debt and then naptime.

As a society, we’re morally opposed to debt. We haven’t evolved too far from our Puritan forefathers in this regard. And deficits make more debt. Abhorring a budget deficit isn’t just an American sentiment. Other inhabitants of Western developed nations fret as we do over deficits. In many places, more so! Come to think of if, they fret over ours, too—more than theirs.

Is any of this anxiety deserved? Looking at the past 20 or so years, America has run a federal budget surplus in just four years. During the budget surplus of the late 1990s, the stock market peaked, leading to a bear market and the start of a recession. That recession was fairly short-lived and shallow, but the bear market persisted three years and was huge. Clearly, the budget surplus didn’t lead to outstanding stock returns. If there is no empirical evidence supporting the hypothesis (yes, Virginia, it’s just a hypothesis) that budget deficits are bad for stocks, could the opposite be true?

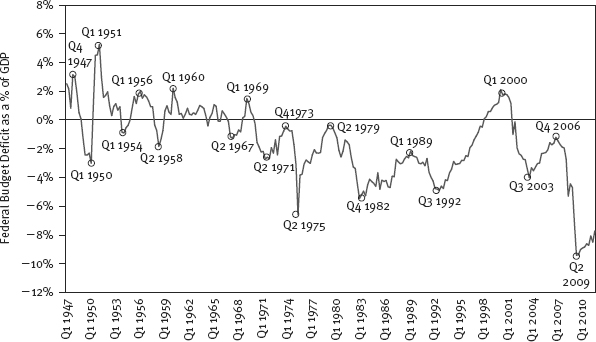

It appears so. Figure 1.6 shows the federal budget balance going back to 1947 as a percent of annual gross domestic product (GDP). Anything above the horizontal line is a budget surplus; anything below is a deficit. We’ve noted relative peaks and troughs. The counterintuitive truth is stock market returns following periodic deficit extremes have been much higher on average than surplus peaks or even decreasing deficits.

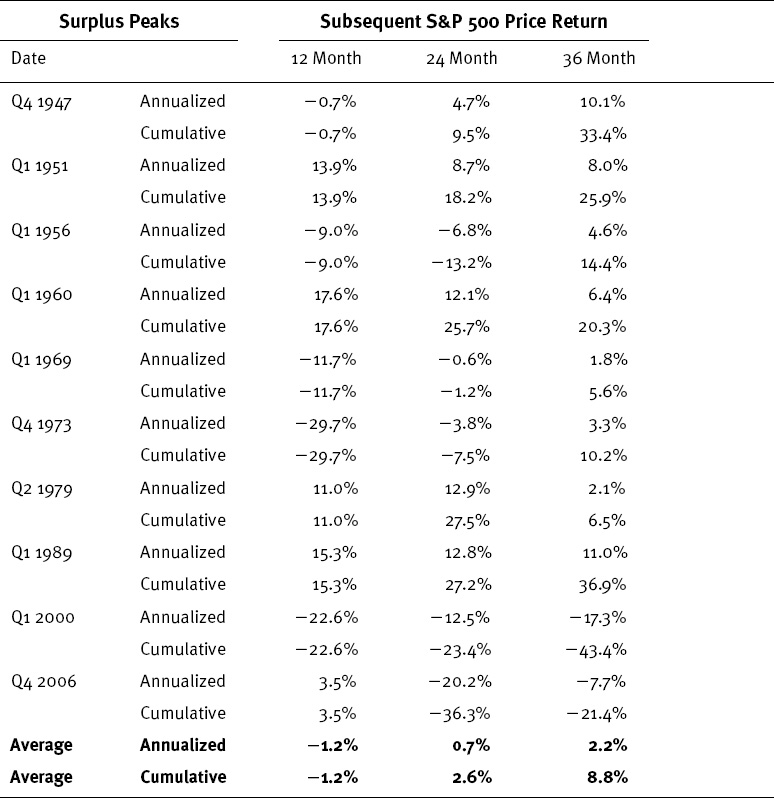

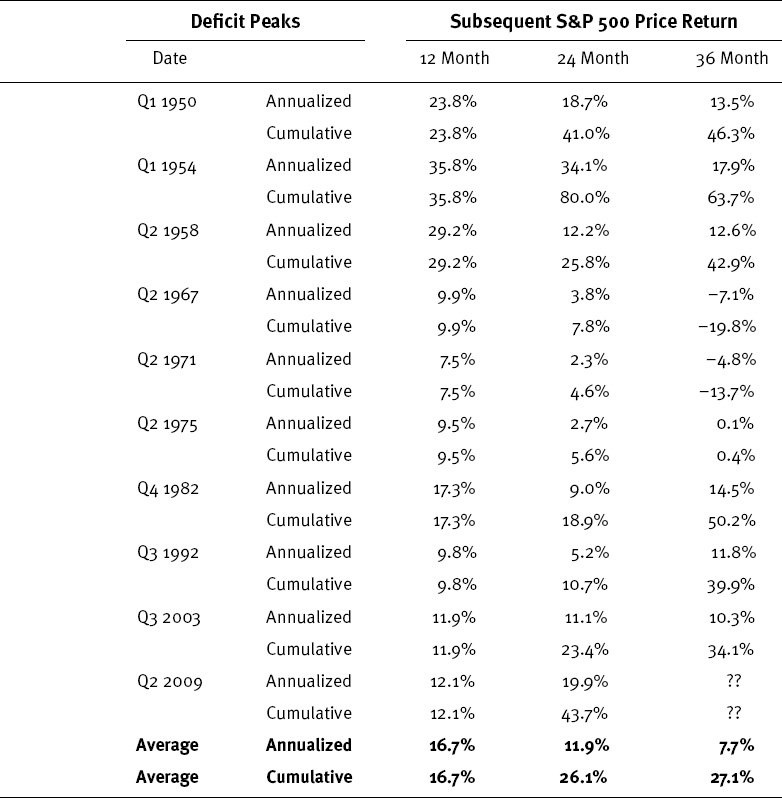

Table 1.2 shows subsequent price returns after surpluses and deficits. Look at the 12-month subsequent returns after budget surpluses and compare with the returns after the deficits. Which world do you want to be living in? The one with the average return of 16.7% or the one with the average return of −1.2%? Now look out over 36-month returns. Those appalling deficits get you an average cumulative return of 27.1% compared with 8.8% from the surpluses.

Table 1.2 Stock Returns Following Budget Balance Extremes

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Global Financial Data, Inc., S&P 500 price index as of 11/30/2011.

The plain truth is, since 1947, if an investor had purchased stocks at federal budget deficit extremes, he or she would have seen one-, two-, and three-year returns much higher on average than if purchased at high budget surplus periods. Buying in the aftermath of budget surpluses would have rendered materially below-average returns.

If you’re beginning to think perhaps budget surpluses aren’t the best thing to happen to stocks, you’re getting it. If you suspect the wry hand of TGH, you’re also getting it. Budget surpluses aren’t a panacea. They historically lead to bad markets. Don’t wish for them.

This may not make sense at first blush. Conventional wisdom depicts a deficit as some sort of gigantic anchor, holding down the economy and ramming debt down its over-indebted throat. As consumers, we’re careful to not overdraw our checking accounts and believe the government should do the same. Many politicians will have you believe deficits must be reduced, and now. There are no politicians saying more debt is good (although there are often politicians advocating tax cuts, which can cause a similar effect).

Let’s Kill the Bloodsuckers

If you don’t know the origin of the word politics, let me enlighten you. The word politics comes from the Greek poli, meaning “many,” and tics, meaning “small bloodsucking creatures.” Unless a poli-tic stands up and announces, “I routinely lie, cheat and steal to help my career and care nothing about you, whoever you are,” you should take anything he says with a grain of salt.

People have some difficulty with this. You know you dislike any poli-tic saying things ideologically you dislike. And you know he is dishonest, a slimeball and someone if whom your daughter planned to marry, you would instead seek a cult deprogrammer to protect her. What you have difficulty accepting is when another poli-tic says things you like and believe in, that he or she is simply lying. Of course, that’s just my view. Suppose I’m wrong.

Poli-tics, overwhelmingly, aren’t students of capital markets. More than anything else they tend to be lawyers (some exceptions—like Presidents Eisenhower, Carter, Reagan and Bush. Or even Arnold Schwarzenegger). Don’t look to them to be experts in finance or economics. They may be honest enough until they become Beltway blowhards, but they still aren’t experts on markets and economics and will never use the Three Questions. Poli-tics never think about when they’re wrong, how to fathom what others can’t fathom and how to see when their brains are misguiding them. Poli-tics couldn’t use the Three Questions if they had to. (Perhaps I’ve been bombastic for comedy’s sake in the past few paragraphs, but you’ll be a better investor and sleep better at night if you tune out approximately 97% of what poli-tics say.)

That budget deficits are good for stocks isn’t a lucky fluke. Economically, it makes sense if you can get yourself to think about debt and deficits correctly. (We cover that in Chapter 6.) For now, suppose budget deficits really are good for stocks in America and surpluses really are bad. If that is true, we ought to be able to see it happening close to the same way in other developed Western nations. That trick is a really nifty one most folks never use. And we do see it overseas.

In other developed nations (as I demonstrate for you in Chapter 6), budget deficits have preceded good stock market returns and surpluses have preceded gloomier times. This isn’t a socioeconomic-political statement. All we are doing is looking at cold hard facts and encouraging you to do the same. Folks who are hamstrung by bias are plagued with misconception and can’t see the truth even when it’s right there in front of them. Instead, always ask if what you believe is actually false.

What About Those Other Deficits?

The federal budget deficit isn’t the only deficit boogeyman getting investors’ knickers knotted. As soon as I tell you the budget deficit isn’t bad for stocks, your reaction may be dismissal, anger and then a framework shift—that other deficits, like the trade deficit, must be bad. You’ve heard it so often. You’ve also heard it’s bad for the dollar.

We look at such assertions in both Chapters 6 and 7, where I show these two forms of deficits aren’t bad for stocks or the dollar. I mention this here as another version of something everyone believes that is false. Note you’ve heard it, accepted it, believed it was true, winced every time a new record trade deficit number was announced but never stopped to ask, “I know I believe it’s bad; but is it really, and how would I check?” Because you know in your heart, if everyone is wrong, and trade deficits aren’t bad for the stock market and the dollar, it would be tremendously bullish because that would be one less thing to fret that to most folks is a huge burden. And that is something you can know others don’t.

It’s All Relatively Relative

Part of the reason investors freak out about deficits—budget, trade and otherwise—is they forget to think relatively (a cognitive error). They hear we have an estimated $500 billion trade deficit (as of the end of 2010).11 “Holy cow! That’s a lot of moo-laa!” they think. “Five hundred billion??? I don’t have five hundred billion. Not even Bill Gates has that much.” News editors and talking heads lambaste whomever they think is responsible, using words like “record breaking,” “staggering” and “irresponsible” to describe the deficit’s size. Well, of course it sounds high. But is it? Are our perceptions right?

To see this correctly, we must scale. We must look at our trade deficit as a percentage of our overall economy. If you think $500 billion is a lot, what do you think about $14.5 trillion? That’s the comparable size of America’s GDP (also at year-end 2010).12 As a percentage of our national income, the trade deficit is a mere 3.4%. What’s more, as a historical average, it’s nothing to sweat about either.

The media won’t mention the trade deficit as a percentage of GDP, however, because they assume you’re rational and won’t get exercised over a trade deficit that is 3.4% of our overall income.

This doesn’t work just with deficits. Anytime the media tries to scare you with huge numbers, think about it relatively—think scale.

Question Everything You Know

Success in investing requires you to question everything you think you know—particularly those things you think you really, really know. Using Question One properly gives you discipline to start preventing some basic errors. The ability to just avoid mistakes is key to successful investing. As you examine mythology and begin discovering faulty logic, don’t simply correct it once and forget about it. Investing is an applied science, not a craft. If you get a validated answer to a hypothesis, don’t assume you can apply the results always and everywhere and get the same result. TGH is an ever-changing opponent requiring constant re-testing of hypotheses.

Knowing big federal budget deficits don’t necessarily signal bad times ahead and may in fact signal the reverse is fairly shocking, though undeniably true. Someday, in some future universe, the investing public may relinquish this myth and realize the whole world has been wrong on this point. Should that occur, you will have lost your edge. Then you will no longer know something others don’t. When everyone knows federal budget deficits are to be cheered not jeered, the market will efficiently price it in. By using Question One and constantly retesting your investing doctrine, you won’t fall prey to such an event, implausible though it is.

You may say (and it’s a great thing to say), “But if you tell me in this book the market’s P/E has nothing to do with future returns and big budget deficits are bullish not bearish, won’t the whole world know? And then won’t it stop working?” If the world embraces these truths, then because the market is a discounter of all widely known information, these truths would become priced into markets and knowing them wouldn’t give you an edge. They wouldn’t work because you wouldn’t know anything others don’t widely know.

But that didn’t happen after I first published this book in 2007. Most of the myths in this book persist. I bet it doesn’t happen in 2012 either. I’ll bet most folks who read Chapter 1 will think the notions expressed about P/Es and deficits are so screwy, they ignore them completely and fall back on the mythologies. That would be comfortable and easy. Most investors will never see this book, and of those buying it, half won’t read it. Of those who do, many won’t get past this chapter in disgust. They will reject the truth, prefer mythology and see me as silly. I hope they do because when I see them see me as silly and wrong, I know I will be able to use these truisms for a long time. If they adopt most of these truisms, I’ll need to come up with new ones to know something others don’t.

Whereas the Campbell-Shiller paper was rapidly embraced and quickly became globally famous and popular because it supported the standard mythology, evidence contradicting market mythologies fortunately tends to be about as noticed as a rock thrown into a lake—a minor ripple followed by near-instant absence from societal memory. This isn’t the first time I’ve written about the high P/E myth. I first started 15 years ago. I’ll bet it is as prevalent 5 and 10 years from now as it is today, and you can still make gameable bets on it. But of course, I could be wrong and then you move onto the next myth. That’s life.

The real benefit of Question One is it allows you to know something others don’t know by knowing where you otherwise would have been wrong but thought you were right. Once you master the skill of doing this, you can improve yourself forever with it. You can keep learning things others don’t know while reducing your own propensity to make mistakes.

Discovering new investing truths is a coincidental result of asking Question One—a lucky accident. If you’re purposefully seeking what no one else knows, you must also learn to use and apply Question Two: What can you fathom that others find unfathomable? Even contemplating such a thing seems pretty unfathomable to most people, but that is exactly what we start doing if you simply turn the page and continue to Chapter 2.

Notes

1. John Y. Campbell and Robert J. Shiller, “Valuation Ratios and the Long-Run Stock Market Outlook,” Journal of Portfolio Management (Winter 1998), pp. 11–26.

2. Kenneth L. Fisher and Meir Statman, “Cognitive Biases in Market Forecasts,” Journal of Portfolio Management (Fall 2000), pp. 72–81.

3. See note 1.

4. See note 1.

5. See note 1.

6. If you’re inclined to data and statistics, I refer you to another scholarly article Meir Statman and I did in the Summer 2006 issue of the Journal of Investing where we show the data for the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan.

7. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk,” Econometrica, vol. 47, no. 2 (March 1979), pp. 263–292.

8. Richard H. Thaler, Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman and Alan Schwartz, “The Effect of Myopia and Loss Aversion on Risk Taking: An Experimental Test,” Quarterly Journal of Economics (May 1997), pp. 647–661.

9. Daniel Kahneman, Paul Slovic and Amos Tversky, Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982), pp. 480–481.

10. Bloomberg Finance, L.P., Bloomberg Fair Value USD Composite (BBB), as of 12/07/2011.

11. US Census Bureau, Thomson Reuters.

12. US Bureau of Economic Analysis, as of 12/31/2010.