Presume at every turn, the market is actually out to get you. I’m not being paranoid—it’s true. I don’t call the market The Great Humiliator (TGH) for nothing. Think of it as a dangerous predatory, living, instinctual beast doing anything and everything to abjectly humiliate you out of every last penny possible. Just knowing and accepting that is the first step to getting the whip hand of TGH. Your goal is to engage TGH without ending up too humiliated. In the next chapter, we talk about how to create a strategy to increase the odds you reach your long-term goals, but first, let’s talk about exactly how to use the Questions to see clearly how the market operates so you can cease being humiliated.

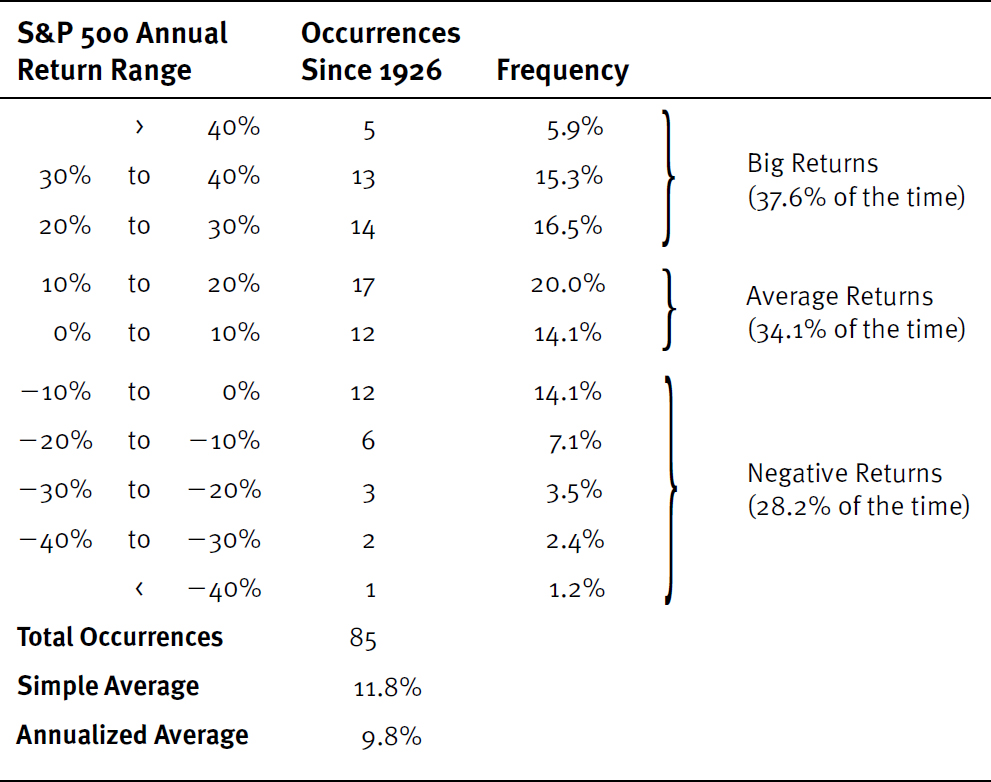

TGH headfakes you by moving in disorderly patterns. We know the market historically has averaged about 10% yearly over long time periods.1 So is it reasonable to expect about 10% absolute returns each and every year? No way. Since 1926, there have been relatively few years the stock market has actually returned something close to the long-term average. Normal market years are anything but average. This is an easy Question One truth shown in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1 Average Returns Aren’t Normal. Normal Returns Are Extreme—US

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., S&P 500 total returns from 12/31/1925 to 12/31/2010.

Not only are returns wildly variable, but it’s a global truth. Think globally and check elsewhere. In the UK, TGH goes by Ye Olde Humiliatour (YOH), as shown in Table 8.2. (In Germany, TGH is Der Grosse Demütiger.) Returns should continue to be wildly variable year to year.

Table 8.2 Average Returns Aren’t Normal. Normal Returns Are Extreme—UK

Source: Global Financial Data, UK FTSE total returns from 12/31/1925 to 12/31/2010.

From this disorder, your brain doesn’t neatly notice the market doing one of only four things in any given year. Those four market scenarios are:

1. The market can be up a lot.

2. The market can be up a little.

3. The market can be down a little.

4. The market can be down a lot.

Markets can do myriad things in short spurts in a seemingly disordered way. But it really does just one of the four things in the course of the year.

These four conditions simply simplify possible outcomes and help you see more clearly and make more disciplined decisions. They also provide a way for you to assert self-control over your behavior—note, I said behavior, not skill—and are the essence of asking yourself Question Three.

Your brain, working with TGH, tries to persuade you the market will do any number of things. But all you must focus on is whether you think it likeliest the market will end up a lot, up a little, down a little or down a lot—looking out about a year. Everything in between is TGH distracting you. Four things! Is it nudging up or down a little, or is it a meltdown or melt-up? (Investors almost never think about a melt-up, but it’s as important as a meltdown.)

Direction, Not Magnitude

Focusing on these four market conditions helps you make the key decisions having the most impact on your portfolio—the asset allocation decisions. The four conditions are a framework for guiding your behavior and keeping your brain from leading you astray.

Also, what’s most important about your forecast is getting market direction right, not magnitude. Why? Because getting the market direction right keeps you on the right side of the market more often than not.

Also, if you expect up a lot, up a little, or yes, even down a little, you want to be maximally exposed to equities (as dictated by your benchmark). It doesn’t matter if you think the market will return 8% or 88%. Either way, if your goal is longer-term growth, your major asset allocation decision should be maximal equities. Your sector weights might be impacted by an up-a-lot versus an up-a-little forecast, but even if you get all of that wrong and still make the decision to stay fully invested in equities and are right, you should enjoy the return you get from getting the asset allocation right. This is all about getting the horse before the cart and not vice versa.

You may rebel at remaining maximally exposed to stocks in expectation of a down-a-little year. Should you try to avoid down-a-little downside by shifting to cash? In my view, only if you’re supremely confident (and not overconfident) you know things others don’t. Otherwise, you’re too likely wrong for what is only a little benefit. Trying to avoid a down-a-little year is the perfect example of a brain overcome by overconfidence. Even if you expect down a little, my view is you should focus on relative return. Beating the market is beating the market, even if your absolute return is negative.

If you think the market will be down a little and want to move heavily away from stocks, ask Question Three. First, you may be suffering from myopic loss aversion, and you should try accumulating some regret. Second, recall you may be wrong and the market might be up a little or a lot instead. The difference between up 5% and down 5% in a year can be just a psychological wiggle toward year-end based on serendipity. But even if you’re right and the market is down a little, the transaction fees you incur selling your stocks or funds, ensuing tax bills on your gains and inherent timing errors outing and inning can seriously reduce any benefit you might gain by skipping a down-a-little move.

Then ask, if you get out, will you know when to get back in? Will you time it right? Probably not and certainly not perfectly! If you’re really looking for market-like returns (and if you’re reading this book, my guess is you are), remember the long-term market average includes negative years. In the course of your long investing time horizon, you will experience periodic downside. You should expect it. Downside is intensely painful to live through but is part of the reality of the long slog that is investing in equities with an aim of getting market-like returns. Renew your faith in capitalism. Grit your teeth and know better times are ahead.

Also, many presume they’d prefer a portfolio that’s up when the market is down, but a portfolio like that likely lags when the market is up. If the market is positive more often than negative (which it is), and you have a portfolio running counter to the market or cutting off the downside at the expense of upside, you won’t average out to be happy.

Recall always: When you go to cash, you adopt massive benchmark risk. You become completely unlike your benchmark. And just think what happens if you’re really, really wrong and there is a melt-up. You incurred transaction costs, paid taxes and lost maybe 25% relatively or more, which comes to about 1% a year over the next 25 years—very hard to make up. This is exactly what people do at the bottom of major bear markets when they choose to remain out so they can wait “for things to become clearer.” In exchange for avoiding a down-a-little possibility, they forsake an up-a-lot market. In my mind, for long-term investors wanting market-like return, there’s no error more damaging.

Look Out Below!

As for the fourth scenario, the down-a-lot scenario, it’s the only time, in my view, it’s appropriate to take on massive benchmark risk by moving heavily away from equities—going to cash or another defensive posture. Then, and only then, should you focus more on absolute return instead of relative return and try to beat the market by a lot. But if you’re right, you get relative return, too. If you are very confident the likeliest outcome is the market being down huge 20% or more—maybe 35%, 40% or even 50%—then it can make sense to try for cash or bond-like returns. Getting a cash-like return doesn’t sound like much, but if you are correct and the market is down a lot, you have blown the market away on a relative basis.

This should be rare and prompted only by something you are supremely confident you know that most others don’t. It shouldn’t be done by gut feel, by fear or by your neighbor’s opinion. The Three Questions should figure in largely here. And the benefits can be huge. If for 30 years, you simply invested in a passive index fund, but just once in those years you sidestepped a 25% drop while getting a 5% cash-and-bond return—over the 30 years, you would do 1% per year better than the market. In the process, you would have beaten more than 90% of all professional investors based on only one correct bet. Getting defensive successfully even just once or a couple of times, even if you don’t do it perfectly, can provide you with a major and lasting performance boost.

At a bull market peak, there is endless advice saying you should never turn bearish and you should never “time the market,” and that people who do are destined to miss the big returns of bull markets. In 2000, this advice was rampant. That is simply TGH sucking you into the bear market as it moves disorderly down a path few will fathom. Make no mistake; the rewards from occasionally seeing a bear market correctly are big enough to justify building your bear market muscle—knowing you use it exceptionally rarely.

After bear markets, the heroes are those who did “time the market” and turn bearish. Many of them will have been bearish way too early—often for years before the bull market peak—having been a “perma bear” (stopped clocks who often have miserable long-term relative returns but are short-term media heroes nonetheless). Alternately villainizing then making heroes of those who went defensive is TGH at its finest as it teases investors’ brains to keep looking backward instead of forward. The key is to keep the bear market timing skill for long periods of time when it’s never used—dry powder for the rare day you need it.

I’ve turned defensive only three times—mid-1987, mid-1990 and late 2000. I was very lucky each time. The next time, I’ll probably screw it up. (Reminding myself of that is one way of reducing overconfidence.) Avoiding a big slice of those bear markets is a huge piece of what built my career. When you avoid a slice of a full-fledged bear market, you simply buy years of excess return. If you went into the bull market peak slightly lagging the market, one successful bypass of a chunk of a bear market catches you up and moves you ahead. It’s hard keeping a skill set you use only a few times in your investing life honed and available. Most folks won’t, which is why you should. They want to hone the skills they use daily, not once a decade.

Getting It Wrong

I wrote “the next time I’ll probably screw it up” late in 2006 (this book was originally published in 2007), and as it turned out, I did not correctly foresee the 2008 bear market. Am I disappointed? Yes. Am I surprised? No. As I wrote here, seeing bear markets correctly is very tough. Making the decision to get defensive and move heavily away from equities is also tough—the toughest and possibly riskiest move a money manager can make from a relative return standpoint.

In my 2010 book, Debunkery, I write more on why, for long-term growth-oriented investors, being fully exposed to a bear market feels bad but shouldn’t derail you from achieving long-term objectives. This is hard for most investors to get—but if you want long-term growth, that is just going to come with market-like volatility and periods of being down. Even down huge. Knowing that can help you avoid making knee-jerk decisions in response to downside volatility that can have much longer-term repercussions.

Building a Defensive Portolio

Suppose you use your Three Questions and are confident the most likely market scenario over the next year (or so) is down a lot—a true bear market. What do you do? What should a defensive portfolio look like? It depends.

You may hate hearing that, I know, but it’s true. Different bear markets are different. In some bear markets, some sectors survive swimmingly, but you won’t know which until it is on you—and maybe not even then.

In sustained bear markets, if you forecast them well, a mostly cash portfolio can make the most sense. Liquidity is key—markets move fast as bull markets begin, so you need to be prepared to get back in. If you’re illiquid or you ease your way back into the market, you’re likely to miss the big bang off the bottom. You can use money markets and short-term government bills. You probably don’t want to buy anything with a long maturity unless it can be sold instantly. Be defensive but liquid.

Market Neutral

As an example, during the 2000 to 2002 bear market, I wanted a portfolio that acted cash-like but with better-than-cash returns. I wanted to be immunized against downside volatility and to be very liquid so I could quickly get back into the market. I wanted tax efficiency. And I wanted to take advantage of knowing something others didn’t by overweighting certain sectors and underweighting others. Since I expected Tech to be weak and had dedicated significant resources to that call, I wanted to get some juice from it. To do that, I had to be market neutral—own equities with sector exposure but no net exposure to owning equities. What does that mean?

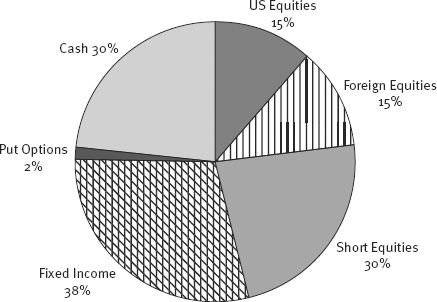

I created what I called a “synthetic cash” portfolio encompassing all those goals. My asset allocation during that time added up to 130% of my real portfolio. (See Figure 8.1.) Here’s how.

Figure 8.1 Hypothetical Defensive Portfolio Allocation

Note: For illustrative purposes only. Not to be interpreted as a forecast.

First, I had 30% in huge, blue-chip, defensive European and US stocks—big drugs, banks and consumer staples. Anything that was considered “defensive,” so cyclicals were out. I wanted companies with inelastic demand for their products, not elastic, since during bear markets folks tend to dial back their discretionary spending. A lot of these were super-cap stocks bought in the late 1990s with capital gains I didn’t have to realize because I didn’t have to sell them. Effectively, you can think of it this way: When the time comes to create synthetic cash, sell what you can that doesn’t involve a capital gain, and then do the index shorting (mentioned shortly) to ensure you don’t lose capital from the bear market decline.

Next, I had about 38% in liquid US government bonds (not too risky).

I had 2% in index puts against the S&P 500. I bought puts expiring about a year out. Index puts are a classic dream—they’re relatively cheap insurance with relatively low premiums at the right time (market tops) and very expensive insurance at the wrong times (market bottoms). Index puts are just like casualty insurance where the casualty is the index dropping big. The puts would pay off handsomely if that happened and simply expire worthless if it didn’t. I had little to lose with such a small position. A 2% loss, if they didn’t pay off, would largely be covered by my bond income. But the portfolio would get considerable juice if the bet paid off. Every time the stocks sagged the puts soared in value.

Then with 30%, I sold short the Nasdaq 100 and the Russell 2000 (20% and 10% respectively), took the proceeds and held it in cash—another 30%. (30% + 38% + 2% + 30% + 30% = 130%. That’s how I had 130%.) My bet was the combination of the Nasdaq and Russell would drop more than the stocks I held. So I borrowed the indexes and sold them short with the hope when they dropped, I could buy them back at a lower price, and the difference was all profit—and bigger than the losses I had on my stocks that fell. Instead of reinvesting the proceeds from shorting the indexes, I held the cash in the event I was wrong. But even the cash earned some income.

This time I wasn’t wrong, and the market fell a lot during those bear market years. This portfolio fared very well in those conditions. The Nasdaq 100 short did a lot better than the Russell 2000, but together they worked just fine, rising in value as the stocks I held fell. I don’t know how I’ll construct my next bear market portfolio, but next time, based on the conditions then, I’ll likely try to create contemporary synthetic cash that is nonvolatile, liquid, tax efficient and still allows for some stock and sector picking.