So—terminal value or cash flow or both? But how do you achieve those goals? And how do you start aiming to be right more often than wrong? Just as you don’t need advanced scholarship or apprenticeship to learn to use the Questions, building a strategy can be as easy as following four rules my firm employs every day in managing money:

Rule Number One: Select an appropriate benchmark.

Rule Number Two: Analyze the benchmark’s components and assign expected risk and return.

Rule Number Three: Blend non-correlated or negatively correlated securities to moderate risk relative to expected return.

Rule Number Four: Always remember you can be wrong, so don’t stray from the first three rules.

Let’s examine these four rules more closely.

Rule Number One: Select an Appropriate Benchmark

You know the benchmark is vital to success. You know what a benchmark should be (well constructed) and what it shouldn’t be (price-weighted like the Dow). As important, your benchmark should be appropriate for you. It will dictate how much volatility you’re likely to experience, your return expectation, even to some extent what ends up in your portfolio. It’s your road map, your measuring stick. You shouldn’t change it, not soon, unless something really radical happens to you, changing the primary purpose of your money. Something materially impacting your time horizon one way or another—like your spouse passing away, which could shorten your expected time horizon, or you remarry a younger spouse, which could lengthen it. Or something materially impacting your goals—like something changes about how much future cash flow you’ll need. So it’s crucial you select the right benchmark for you.

Your benchmark can be all equity (as we discussed), all fixed income or a blend of the two. Picking a benchmark—deciding if you need an all-equity, blended or even an all–fixed income benchmark—depends primarily on four things. Throw the nonsense “risk tolerance” survey baloney out the window. The four factors for figuring which benchmark is appropriate for you are: (1) your time horizon, (2) how much cash flow you need and when, (3) your return expectations and (4) any other portfolio-specific needs unique to you. For example, you’re a senior executive for Big Company X and therefore can’t own their stock. Or you don’t want to own so-called sin stocks (tobacco, gambling, whatever you choose). Or you have weird but strong-felt views, like you hate the French or don’t want to own stocks that produce you-name-it—tofu—whatever.

Risk-Tolerance Baloney?

Since I first wrote this book, now six years ago, a few folks have criticized the line: “Throw the nonsense ‘risk tolerance’ baloney out the window.” For folks doing a surface read (i.e., not reading the many pages leading up, or any of the pages that followed), they presume that means I don’t think risk tolerance matters. They are incorrect. Risk tolerance does matter. Very much! In fact, this entire chapter (and, indeed, the entire book) is basically about risk tolerance and determining the appropriate amount of risk to take to increase the likelihood of achieving an investor’s goals!

What I believed then (and believe now) is “baloney” is the idea there is some kind of check-the-box survey that can correctly assess the amount of risk someone can tolerate. Instead, understanding what amount of risk is appropriate to increase the likelihood of reaching investors’ long-term goals requires a deeper understanding of their time horizons, goals, cash flow needs and any other factors unique to them that may impact portfolio strategy. That means doing an in-depth discovery process and then periodically revisiting the time horizon, goals, needs, etc., to ensure the strategy remains appropriate.

In my view, you can’t accurately determine someone’s tolerance for risk and build an appropriate strategy by asking them to tick a few boxes at one point in time.

The First Determinant: Time Horizon

Your time horizon may be your life expectancy but could be longer. Unless you hate your spouse, you should consider his or her life expectancy as well, which may extend your time horizon. If you like your kids and want to leave something behind for them, that also extends your time horizon. Simply put, your time horizon is how long you need your assets to last. Your time horizon is decidedly not how long it is until you retire or plan to start taking distributions. Far too many investors think wrongly about time horizon; they aren’t using Questions One and Two to see this clearly.

Cookie-Cutter Time Horizon

The financial services industry in some part has promoted wrong thinking about time horizon, in my view. You’ve probably heard the old adage: “Take 100 (or 120), subtract your age, and that’s the percentage you should have in stocks.” This presumes the only factor that matters is your age! But there are myriad other factors that should be considered. I address time horizon further in Chapter 4 of my 2010 book, Debunkery.

You very often hear people say something like, “I’m retiring, so I must become conservative, and I can’t take risk.” But suppose you’re a 65-year-old man, and your wife is 60 and likely to live to 90 (very common). Then you may have a 30-year time horizon that includes a third of her whole life! If you move heavily away from stocks, history says she’s likelier to suffer aged poverty. Now, if you really hate her, then aged poverty is a pretty good idea. My guess, though, is that’s not the intention of most people reading this book.

You may have some reasonable date in mind for when you plan to start living off your assets, but the money still needs to work your whole life or beyond, or you or your loved ones will suffer. That whole period is your time horizon.

You might have a shorter time horizon for some reason—maybe you’re a 32-year-old who needs every penny to pay for that first home in three years. But in most cases, investors tend to grossly underestimate their time horizons. Because both my parents lived well into their 90s, it’s easy for me to envision long time horizons. It’s late in life people need their money because there are so many comforts that benefit the aged that aren’t covered by any form of health insurance.

Stocks or Bonds? The 896% Question

If your time horizon is over 20 years—and if you’re reading this book, it probably is—an all-equity benchmark may be most appropriate for you. Not guaranteed, because you must also consider cash flow needs and other factors. But over long time periods, stocks are by far the best-performing liquid asset class historically, and the likelihood stocks outperform bonds is great. Since 1926 through year-end 2010, there have been 66 20-year rolling time periods. In 64 of them stocks have outperformed bonds by a wide margin. 2 That’s 97% of the time. In return for investing in stocks over a 20-year period, folks got an average return of 896% compared to 245% for bonds. During the two 20-year periods when bonds beat stocks, bonds returned an average 262% and stocks 243%—bonds outperformed by a 1.1-to-1 margin. 3 Not much—and stocks were still positive. Over history, it’s been better to take on the odds and get the superior return.

Over even longer periods, there’s simply been no contest. Measuring 30-year rolling periods, on average, stocks have returned 2,473% and bonds 532%—stocks beat bonds by a 4.6-to-1 margin on average. And bonds have never beat stocks over 30 years. 4

You may feel as though I’m banging an equity drum. I am a big fan of stocks because of their superior longer-term returns (and lots of other reasons—recall that I pray at the altar of Capitalism’s multitudinous blessings, and you can’t have Capitalism without stocks), and I do believe folks frequently underestimate the proportion of stocks they should have in their benchmark. However, there are times when stocks do lousy—in a bear market—and avoiding a down-a-lot world through cash holdings can be a great tactic. But it’s not a strategy.

The Second Determinant: Cash Flow

After determining time horizon, next consider cash flow needs. But it’s not as easy as saying, “If you need 3% cash flow, you should have X% fixed income in your benchmark. If you need 4%, you need Y%.” You must weigh such considerations against your other objectives and the likelihood of long-term survival of the assets.

Said another way: Two couples with identical time horizons, similar size portfolios and identical cash flow needs as a percent of their portfolio may well need very different benchmarks. Just because they are different people with different long-term objectives.

For a couple who needs 4% cash flow, a 100% equity benchmark may be appropriate if they are equally (or more) focused on growing their portfolio. The other couple may care much more about just the cash flow—doesn’t want to leave anything to kids or grandkids. They just need their portfolio to stretch enough to cover the cash flow. For them, a bigger allocation of fixed income in their benchmark may be appropriate.

Still, even with a blended benchmark—60% equity and 40% fixed income or 70%/30% or whatever—there may come a time when you should boost your cash to 100% to be defensive temporarily, and you shouldn’t get lulled into a false sense of security with a blended benchmark. Your benchmark is your road map but not necessarily what you own all the time. In a major bear market, you’ll still lose money with a rigid fixed allocation. Sometimes you need a detour. Or a dividend!

Homegrown Dividends

Another reason investors hit a panic button at or near retirement and believe they should plow all of their hard-earned assets into bonds and high-dividend-paying stocks is they may think they need the coupon payments and dividends for income. They believe if they kick off a decent percentage in income, they can sit back and let the portfolio provide for retirement. As mentioned earlier, this confuses income with cash flow.

Use Question One for this myth (and it is a myth). Is it true a portfolio stacked with bonds and high-dividend stocks will provide income throughout retirement? Maybe! Maybe you’re worth $10 million and want only $50,000 a year. Maybe you don’t need your assets to grow so your income doesn’t get degraded by inflation. Maybe it doesn’t matter much if you see your assets diminished through reinvestment risk or if the high-dividend-paying stocks tank in value.

But most folks reading this probably can’t afford to have their assets stagnate or decrease significantly throughout retirement. What happens when you reinvest a maturing 6% bond from 2001, and the only thing you can buy in 2011 that isn’t risky yields 1.5%? And how about when that dandy utility stock paying an 8% dividend depreciates 40% in price? That company likely slashes its dividend—a rational thing to do. Then, too, a lower percent of a lower market value is probably not what you were banking on. And what about inflation?

It’s simply not true coupon payments and dividends are a surefire “safe” way to garner income from your portfolio. But how else do you get cash? If you have an all-equity benchmark and you need cash flow, you don’t want to sell stock to provide cash for yourself. Do you?

Well, why the heck not? What’s it there for? This is a Question Two solution I’ve come up with for maintaining growth while providing cash flow from portfolios, and I call it homegrown dividends.

Let’s say you have a million-dollar portfolio, and you take $40,000 a year in even monthly distributions of $3,333 a month—give or take. You should keep about twice that much in cash in your portfolio at all times so you don’t rush to sell a nitpicky number of stocks each month. Then you can be tactical about what you sell and when. But you’re always looking to prune back, planning for distributions a month or two out. You can sell down stocks to use as a tax loss to offset gains you might realize. You can pare back overweighted positions. You’ll probably always have some dividend-paying stocks to add some cash, but that is a derivative of picking the right kinds. Homegrown dividends are tax efficient, cheap to raise and keep you fully and appropriately invested.

The Third Determinant: Return Expectation

The third factor in selecting an appropriate benchmark is return expectation. If you’re 50 and want to retire in five years and need $500,000 a year in cash flow to maintain your lifestyle and have $2 million total saved in your portfolio, you’re in for a caught-with-your-pants-down rude awakening. Your return expectations are gonzo high. Unless you anticipate a windfall on the order of $10 million (or so) sometime in the in-your-dreams future, plan instead on taking $80,000 a year or less and get over it. Or keep working. Start figuring out a way to explain this to your wife (or husband) now.

But imagine an investor, call her Jane, who has a reliable income source lined up for her retirement (a pension, perhaps, with some rental income). She doesn’t need her assets to grow to provide for her and her husband. Jane intends to leave her money to her kids but doesn’t really care about maximizing terminal value. Instead, she is nervous about volatility and looking for that sleep-at-night factor.

For her, an all-equity benchmark may still be appropriate. Maybe not. You’d need to know more about her—but don’t automatically rule out any options yet.

Why? Because Jane has a long time horizon and needs no income. I’d want to understand more of what she thinks volatility is and how that would impact her. And I’d want to more deeply understand her goals. And what is it that’s keeping her from sleeping at night, exactly? What makes investors sleep at night can differ radically. As stated earlier, few investors envision their future risk orientation correctly. If you base a long-term strategy solely on how you feel right now and ignore all other factors, you could be making a major mistake. Will Jane feel differently in three months, nine months or a few years? And, 20 years from now, will Jane find she really can’t sleep at night because she avoided stocks too heavily and now has much less of a portfolio cushion than she envisioned? You have to consider that among the other factors that influence a benchmark decision.

The Fourth Determinant: Individual Peculiarity

Just because most investors have similar goals and aren’t as unique as they think doesn’t mean they’re not peculiar. This isn’t about “being uncomfortable” with foreign investing, Health Care stocks, Tech, Emerging Markets or whatever because that could be more stubbornness than peculiarity. This is about having strong feelings about a particular company or a narrow sector deriving from personal belief, peculiarity or some other situation unique to you. And it’s ok to create a customized benchmark reflecting your own weird idiosyncrasies.

You may simply want to never, ever own a French stock. Or the stock of a firm making tobacco products. Or a firm making tofu (ugh!). Or maybe you work for publicly traded firm ABC and can’t own its stock. Whatever! It’s fine to have a customized benchmark that is the World ex-France. Or the World ex-France and ex-tofu. Or ex-ABC. All fine reasons, and all should be considered as you select your benchmark.

Since all major categories should have similar long-term returns, the degree of return variation caused by those slight variances from a vastly bigger and maybe global benchmark won’t be enough to count. And they’ll make you feel better about what you’re doing so you’re more likely to keep doing it. There are no investors who have had a bad investing history having otherwise done portfolio management right because they chose to create their own customized benchmark that was the World ex-Iowa (for those of you who divorced someone from there once. Still, were I you, I’d rather get my revenge on the Iowans by buying Iowa stocks too cheap).

Whatever it is, you may have strong enough personal feelings to warrant a particular benchmark free from some offending stock or microsector. But watch if you start having feelings about whole sectors because that might be driven more by loss aversion and hindsight bias than your own individual freakiness. Plenty of investors decided they had developed a severe allergic reaction to Tech post-2002. That is a cognitive error, not a peculiarity.

So, the amount of risk appropriate for your long-term goals should be driven primarily by (1) time horizon, (2) income needs, (3) return expectation and (4) extreme individual peculiarities. Jane may consider herself risk averse now, but in 1999, did she consider herself aggressive and overweight to Tech stocks? She might feel differently again, depending on what the stock market has done in the near and immediate past. That can be a dangerous way to build a long-term strategy. Feelings can change fast. What typically don’t change much, not without a major event, are how long your assets must last and how much cash flow you will take. And, of course, if you’re morally opposed to tobacco now, you probably will be in the future, too. That won’t go up in smoke.

I’m not saying you must have an all-equity benchmark if it will cause (or exacerbate) ulcers. I’m just saying the cause of the ulcers may be something else. Explore it a bit before committing to a benchmark, long term.

Heat Chasing—To Shift or Not to Shift

Choose your benchmark carefully because once selected, it’s yours for a very long time—maybe the entire life of your assets. Superficial benchmark shifting is a recipe for disaster. Let’s call benchmark shifting what it really is—heat chasing. When someone shifted their benchmark from the Nasdaq in 1999 to the Russell 2000 Value Index in 2005, you know they were matching their benchmark to what had been hot—simple heat chasing. People chasing heat forget about transaction costs and taxes and invariably in-and-out relatively backward—lagging the market by going into what used to work instead of what is likely to work moving forward.

You now know all well-constructed benchmarks should get to about the same place over the very long term. If you get the urge to switch benchmarks, check yourself and ask Question Three. Benchmark switching can be the direct result of regret shunning and pride accumulation, possibly some order preference and overconfidence to boot. Don’t give in. If you switch, you may end up chasing heat and missing returns altogether. Only heartache and harm come from it.

There are two good exceptions to this rule—only two. One is if something happens to drastically change the primary purposes of your money, including your time horizon. This is the 75-year-old in bad health from a short-lived family with a 70-year-old wife in good health from a long-lived family where the wife dies unexpectedly in a car crash. No kids, no charity and his time horizon just collapsed. That’s a good justification for switching to a benchmark more appropriate for a new shorter and sadder time horizon. Or the other way around: Maybe late in life you remarry a younger or healthier person, extending your time horizon. It would be ok to switch to a more appropriate benchmark then, too. Included here would also be a change to cash flow needs. Maybe later in life you discover you need more cash flow from your portfolio. Or less! Either one would warrant a reexamination of the benchmark.

The second reason to switch benchmarks, beyond a change in the fundamentals of your life, is if a future benchmark is created reflecting the same universe as your current benchmark—but the new one is somehow better constructed. This is purely tactical. Here is an example: The MSCI World Index is an excellent, broad benchmark, but it doesn’t include Emerging Markets, restricting itself to developed markets. Then MSCI created the ACWI. Same construction but broader. That should be better for the whole world.

Should you use one over the other? In my mind, it isn’t a big deal one way or the other, and I’m prone to not switching—it’s hard to argue the one is drastically superior to the other. If you’re currently using the MSCI World, the time to switch would be when ACWI was older, after a period when Emerging Markets had done lousy for years.

The whole World-versus-ACWI issue is sort of like choosing either the northern 80/90 route or the southern 70/44/40 route to motor across America. Either is an ok benchmark and gets from East to West Coast just fine. But if there were a new world index—improved and drastically more reflective of the whole world stock market—that would justify switching, too. What I want you to see is it takes something pretty material to justify a benchmark switch.

Rule Number Two: Analyze the Benchmark’s Components, Assign Expected Risk and Return

The second rule of portfolio management helps determine what exactly belongs in your portfolio, how much and when. Your benchmark, particularly if you use a broad one, will be made up of different components, as discussed in Chapter 4. The Nasdaq is fairly easy—do you think Tech will do well this year or not? But unless you seek an exceedingly bumpy ride, we’ve already established you probably shouldn’t use Nasdaq as your benchmark.

No matter which benchmark you pick, it’s your guide for building your portfolio. If your benchmark is about 60% US stocks, your starting point for your portfolio should be about 60% US stocks—unless you’ve used the Questions to know something others don’t. (If you have, you might at a point in time own no stocks at all.) If your benchmark is about 10% Energy, you should be about 10% Energy if you don’t know something others don’t. (But if you think you know something others don’t, you might own no Energy, 5% Energy or be double weight at 20% Energy because you have the basis for a bet.) Your aim is to perform similarly to your benchmark if you don’t know something others don’t and better than the benchmark if you do believe you know something. Of course, the more you know that others don’t, the bigger you might make your bets, and the more dissimilar you might be to your benchmark. (If you can’t recall how the heck to tell what “components” are in your benchmark, flip back to Chapter 4.)

Nervous about doing it right? Don’t be. If you have less than $200,000 or so to invest, you will probably and primarily be buying funds anyway. There are plenty of index funds that can get you the exposure you need. For example, if the S&P 500 is your benchmark, you’re covered beautifully with an S&P 500 index fund. Using the MSCI World or ACWI as your benchmark? Check www.msci.com for the approximate weight of the United States relative to the world (it’s been fluctuating around 50/50). Buy the aforementioned S&P 500 index fund with half your dough and an MSCI EAFE (Europe, Australia, Far East) index fund with the other half. Want to beat the market? It’s harder to do if you have fewer choices to make, as you will with funds. This is why a broad benchmark with lots of components gives you more market-beating opportunities. You can use your Three Questions to make foreign versus US bets. And you can use other ETFs to make bets on sectors or styles without ever owning individual stocks, which is hard to do with a smaller portfolio.

If you’re richer, you can and should buy individual stocks. The more money you have, the higher the proportion that should be in underlying stocks because, in large volume, stocks are cheaper to own than anything including mutual funds, ETFs or any other form of equity. One benefit of stocks is they’re cheap to buy and pretty much free to hold. But whether ETFs or individual stocks, start paying attention to individual sectors and subsectors now. All this information is also on the index’s webpage. For example, your components and their weights will look something like Table 9.1, where we have listed the percentage weights of countries and sectors in the MSCI World Index as of September 30, 2011.

Table 9.1 MSCI World Index Weights—Sectors and Countries

| Sector | Weight |

| Energy | 10.9% |

| Materials | 7.3% |

| Industrials | 10.7% |

| Consumer Discretionary | 10.4% |

| Consumer Staples | 11.1% |

| Health Care | 10.5% |

| Financials | 18.1% |

| Information Technology | 12.2% |

| Telecommunication Services | 4.6% |

| Utilities | 4.2% |

| Country | Weight |

| Austria | 0.1% |

| Australia | 3.7% |

| Belgium | 0.4% |

| Canada | 5.2% |

| Switzerland | 3.8% |

| Germany | 3.4% |

| Denmark | 0.4% |

| Spain | 1.5% |

| Finland | 0.4% |

| France | 4.0% |

| Greece | 0.1% |

| Hong Kong | 1.2% |

| Ireland | 0.1% |

| Italy | 1.0% |

| Israel | 0.3% |

| Japan | 10.1% |

| Netherlands | 1.1% |

| Norway | 0.4% |

| New Zealand | 0.1% |

| Portugal | 0.1% |

| Sweden | 1.3% |

| Singapore | 0.8% |

| United Kingdom | 9.7% |

| United States | 50.9% |

Source: Thomson Reuters, as of 09/30/2011.

You should check back periodically to ensure nothing has gotten out of whack. Don’t feel compelled to rebalance if your portfolio or the benchmark has shifted a few percentage points here and there. Don’t sweat the small stuff. Think about rebalancing once or twice a year unless there is a major sector or country move or you come upon something in between where suddenly you know something others don’t. You’ll make fewer mistakes and pay fewer fees. Trading too often is a byproduct of overconfidence (thinking you have the basis for a bet when you don’t).

With benchmark components in hand, move on to assigning expected risk and return. Suppose you’re using the ACWI. It’s made up of 45 countries, including America.5 Which countries should perform well this year, and which should lag? Use the Three Questions to see if you can find something that might make you favor one country or region more, another less.

The same goes for sectors. Use the Three Questions to decide if what you know about current economic, political and sentiment drivers favors one sector more than another. (Also, if you want more of a primer on analyzing sectors, I recommend the Fisher Investments On series, published by Wiley.)

The object is to make bets that are right more often than wrong while managing risk relative to the benchmark. Correlate the size of your bet according to how confident (but not overconfident) you are. Yes, a bigger over- or underweight has the potential to pay off big if you’re right. But big bets can just as easily go the other way.

If Technology is 20% of your benchmark, and you’re really, really confident it will hugely outperform, maybe you double that weight—to 40%. But that’s a huge overweight—maybe as big as you ever want to go. Remember you must take that weight away from something (or somethings) else. If you’re right, that’s a big win for you—this time. But if you’re wrong and Tech tanks, you may have taken weight away from something that performed better—dinging yourself twice. Are you prepared to handle that? Use your benchmark as a leash to keep your bets in line with how confident you are.

What if you can’t find something others don’t know, and you don’t feel comfortable making a particular forecast for a country or sector? Just be neutral. The idea is to be right more often than wrong, not lucky and right some and unlucky and wrong more.

Rule Number Three: Blend Non-Correlated or Negatively Correlated Securities to Moderate Risk Relative to Expected Return

Most investors, even new investors, understand intuitively diversification helps reduce risk. Remember the poor Enron employees with their 401(k)’s all or mostly in Enron stock? Huge stock-related losses can be avoided through diversification. Companies go bankrupt for many reasons. Stocks implode for even more reasons. The CEO may have done nothing wrong—just couldn’t compete with fire-breathing competitors. The stock of a perfectly healthy firm can tank for no seeming reason—with no forewarning. This is why no one stock should make up too much of your holdings.

My father was a lifelong advocate of concentrated portfolios. Warren Buffett has always been an advocate of concentrated portfolios. Yet I say to you the only basis for a concentrated portfolio is near-infinite faith you know a lot others don’t know. That won’t allow for overconfidence. You must be certain you’re not overconfident. If you don’t really know a lot others don’t know, concentrating portfolios is simply an exercise in overconfidence and increased risk. Stick to the general guideline of never owning more than 5% of one stock.

Owning less than 5% of one stock doesn’t mean in just one account. If you have a 401(k), an IRA and a taxable brokerage account, make sure you keep single stock ownership to less than 5% across all of your accounts.

The 5% Rule?

In my 2010 book, Debunkery, I clarify this rule a bit more. The 5% rule applies if you’re buying publicly traded stocks. But many super-rich founder-CEOs got that way by plowing everything into one stock—the firm they founded, own and operate. The entrepreneur road to riches can be insanely lucrative, but it is a very rocky road. (Read more on that topic in my 2008 book, The Ten Roads to Riches.)

You’ve heard the saying, “You must concentrate to get wealth, diversify to protect wealth.” Those who got rich on 1, 2 or 10 stocks are, very likely, insanely fortunate. Yes, with one stock you can experience thrilling upside. You can also experience crushing downside. Note the guy who gets lucky and wins this way likely accumulates pride and assumes he is smart. His wife and kids will know better and the more so for his success. (Of course, by this I don’t mean owning one stock that is a firm you started and control. That’s how Bill Gates and any number of other super-rich people got their riches—they started and built a firm, nothing else, and along the way got phenomenally rich. I’m talking about being concentrated in one or a few stocks you don’t control.)

The Magic of Diversification

Since no one equity type outperforms all of the time (which you can test for yourself again using Question One), diversification helps spread risk among countries, industries and companies.

Though there are really many types of risk, standard finance theory defines risk as volatility measured by the standard deviation or variance of returns. Most investors think when the market is up, it’s good and when it’s down, it’s volatile. But volatility is a dual-edged sword and ever present. Your question should be: Is this category or stock more or less volatile than its peers? Diversification reduces the volatility of your overall holdings and therefore reduces risk. Modern portfolio analysis has shown even a random mix of investments is less volatile than putting everything in a single category.

Make sure your portfolio has elements behaving differently in different market scenarios—which happens naturally if you have a broad enough benchmark and obey it. Each sector or country in your benchmark moves differently than the others. Maybe a bit differently, maybe very differently—but different all the same. If you follow Rule Number Three and keep those sectors and countries that have low or negative correlation in your portfolio at all times, even if you suspect they won’t be your portfolio MVP, you’ll reduce overall volatility.

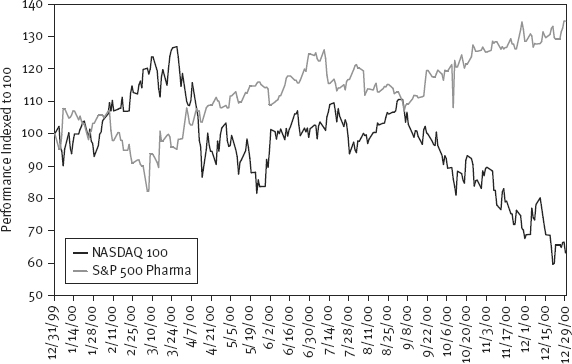

A good example is Technology and Health Care: These two sectors often have a short-term negative correlation—one is up when the other is down. Notice in Figure 9.1 the performance of the two in 2000 is nearly a mirror image.

Rule Number Three, blending dissimilar elements, is about managing risk relative to return. The standard deviation, which is a risk measure, for each sector during the time period was 3.5% for Tech and 2.5% for Health Care. But if you had half your portfolio in each sector (not a good idea, but pretend for illustration’s sake), your standard deviation, and therefore your volatility risk, was actually 2.0%.6 You got lower risk simply by holding two differing kinds of stocks which, over this time period, had a negative correlation.

Then again, maybe you used the Three Questions to develop a strong confidence one would best the other. By all means, overweight the one and underweight the other. Rule Number Two helps you—just be sure to include all your benchmark’s components and you should have a well-blended portfolio.

But having reverse-correlated positions in your portfolio is like paying an insurance premium against being wrong. This doesn’t just work for components with negative correlations. Finance theory is clear: having any blend of dissimilar categories—whether they have negative, low or no correlation—should improve return over time while lowering risk. (Use Question One to test it out. Take any two, four or six stocks from different categories and test over long periods.)

Rule Number Four: Always Remember You Can Be Wrong, So Don’t Stray From the First Three Rules

Rule Number Four, possibly the most important rule, is about controlling your behavior. It’s a way to ensure including Question Three—always. Without this rule, you can be carried away by cognitive errors. Rule Four forces you to accumulate regret and shun pride. With Rule Four, you reduce the risk of being overconfident. Anytime you’re tempted to disregard the first three rules and make a decision not based on the Three Questions but on some herd mentality or Stone Age inclination, Rule Four keeps you in line. With every decision you make, regardless of how confident you are, you can always be wrong. Once you accept that, you’re less likely to do something too crippling.

Rule Four forces you to use your benchmark like a leash for a puppy in training. With a short leash, your pup can’t get in too much trouble. The same dog on a long leash can dig up a garden, get hit by a car or chase a stray cat across town.

For example, suppose you’re confident Tech will do well this year. Tech is 15% of your benchmark. But you’re not satisfied with overweighting it to 20% or even 25%. You know Tech will be tops. Your confidence tempts you to jettison all your Health Care stocks for an even larger Tech allocation because you know Health Care typically lags when Tech is hot. Before changing your portfolio, ask yourself, “What if I am wrong?” Are you prepared for the consequences of such a big bet?

Core Versus Counterstrategy

This rule is the primary reason I manage money with a core strategy and a counterstrategy. The core strategies are market bets I make—relative benchmark overweights—based on what I believe I know that others don’t. For example, if I believe America will outperform foreign, Tech will outperform Health Care, Consumer Discretionary will outperform Consumer Staples, I make overweights relative to the benchmark in those areas. Those are my core strategies.

Then I build my planned counterstrategies. These are areas I don’t expect to do well. I have them there because—what if I am wrong? Hey—I’m wrong a lot. I’ve been fortunate to be right more often than wrong in my career, but I know I’ve been wrong and will definitely be wrong again and plenty of times. Each of the counterstrategies is an area I expect to do well in the event one of my core strategies fails and does badly. If I’m wrong about Tech, Health Care will likely be a better-performing sector. Either American or foreign stocks will be the lead pony, so I don’t want to miss out if I’m wrong about that. I always ask myself, “What will do really well if what I think will do well actually does badly for some reason I can’t foresee?” I want some of that, too. Most investors never think this way.

Having a counterstrategy means you’ll always have “down” or “laggard” stocks. If you’re really right like you expect, your counterstrategy stocks should be down or lagging. Counterstrategy stocks being down isn’t bad. They can keep you from getting killed when you’re wrong. That’s managing risk, which is good. One thing about my career I’m pleased with is when I’ve been wrong and lagged, I haven’t lagged by a lot. And I haven’t lagged by a lot because I’ve built in the counterstrategies.

Here’s a practical example of core and counterstrategies, again using Tech and Health Care for consistency. Pretend you’re benchmark neutral on every sector but Tech and Health Care. You’re new to this Three Questions thing, so you focus on just Health Care to start. You believe you’ve uncovered something no one else is seeing which should make Health Care super hot. Maybe you discovered every member of Congress hit their heads over the weekend (I’d vote for that). You also know the congressmen (and women) have a vote pending Tuesday on drug regulation. They want their new pain relief medicine, and fast, so they’ll do something contrary to their nature—reduce governmental control. As such, you believe the FDA will begin green-lighting a whole slew of insanely efficacious drugs. (I said we were pretending.) No one else sees this. Everyone else thinks congressmen with headaches are bearish because they believe it will make them groggy and stupid. But you know better! (You know they were already idiots.)

Based on your unique view, you decide to overweight Health Care. You’re confident—but not insanely confident—so you decide to increase your Health Care holdings to 15% from a benchmark weight of 10%. That is a 50% overweight and constitutes your core strategy.

Now, unless you’re using margin, your assets must add up to 100%, not 105%, so you must reduce holdings elsewhere. Where? Suppose Tech is also 12% of your benchmark. If drug stocks do badly, your full 12% Tech weight will soften the blow—that’s a counterstrategy. But if you’re very confident about your drug play, you could take the whole 5% out of Tech, decreasing your Tech weight from 12% to 7% and increasing the real size of your bet by minimizing how much counterstrategy you have. You still have a 7% weight, but it is a smaller counterstrategy than if you took the 5% haircut from elsewhere.

Thinking it through with the Questions, you discover most folks agree Tech is undervalued because Tech P/Es are low. Also, the dollar has been strong recently (for argument’s sake) and folks expect that to continue, and from that, they think US stocks will be strong. Everyone remembers the 1990s when America led and so did Tech.

But you know low P/Es aren’t automatically low risk, high return. You know a strong dollar last year doesn’t mean a strong dollar this year. You also know a strong dollar doesn’t make American stocks beat foreign. Noting the near-universal bullishness on Tech, you conclude you really won’t need a full counterstrategy and decide to underweight Tech by the full 5%—putting your weight at 7%.

Still you have a counterstrategy that helps if your core drug strategy fails. If you’re right about Health Care, you’ll probably (but not necessarily) also be right about Tech, and you’ll have participated more in a hot sector and less in a lame one. You beat the market, just from getting one core and one counterstrategy right (in this case by betting big and minimizing your counterstrategy).

Now, you could have been more extreme. You could have moved your Health Care weight from 10% to 22% and your Tech weight from 12% to 0%. And if it worked, you would have won huge. But you didn’t. You kept that 7% in Tech.

Suppose you’re wrong about your head injury theory. Congress convenes with nothing more than a few mild headaches. The poli-tics ban all pharmaceuticals except aspirin. No one expected that, so Health Care tanks, and folks flock to a “hotter” sector, like Tech. Two sector bets wrong. You’ve participated less in the hot sector and more in the lame one. Ugh! You lag benchmark. But not by much, because you didn’t go nil in the hot sector, and you didn’t grossly overweight the laggard.

It’s never all that bad to lag the benchmark by a few percentage points in a single year—maybe you do 16% or 17% when the benchmark does 20%. After all, this isn’t a game where slight differences in one year’s performance count all that much. If you lag by a little for a few years, you can always make that up (the operative words being “lag by a little”). You have the rest of your life to be more right than wrong.

In a year when more of your core strategies are right, you meet or beat your benchmark. There have been up years when I’ve been wrong about most of my core strategies, but because I got the big decision right—the decision to hold stocks instead of cash or bonds—I lagged my benchmark but not too badly and not by an amount I couldn’t make up later. Why? Because I never aim to beat by more than I am comfortable lagging. The counterstrategies save you from lagging too much in years you’re wrong.

The only time I am ever comfortable beating the benchmark by a lot—taking on massive amounts of benchmark risk—is when I believe down a lot is by far the likeliest scenario. Then, if I forecast down a lot, I will try beating the benchmark by a lot to avoid the bulk of a bear market. It’s a much riskier move than folks realize—huge benchmark risk—and must never be undertaken lightly. But over long time periods, if you beat the benchmark modestly on average and beat the occasional bear market by a lot, you put serious spread on TGH. It’s the only time I want to embrace huge benchmark risk.