There’s simply no single answer to the question: What causes a bear market? It might be monetary conditions, yield curve shifts, surpluses, a sector implosion, excess demand reverting or bad legislation impacting property rights. But it likely won’t be what it was last time. Two bear markets in a row rarely start with the same causes because most investors are always fighting the last war and are prepared for what took them down last time.

Maybe you suspect a bear market will start because the bull market has run on too long. Question One—is there a “right” time a bull market needs to last? No! There is no “right” length for a bull market. As bull markets run longer than average in duration, there is normally a steady stream of folks who say a bull market must end because it’s too old. (Read more on this phenomenon in Markets Never Forget.) That isn’t right. They all end for their own reasons and will end eventually—but age isn’t among them. People started saying the 1990s bull market was too old in 1994, only about six years too soon. “Irrational exuberance” was first uttered in 1996—again, way too early. Bull markets can die at any age.

Use your Questions to test some of these. Find a few of your favorite indicators and see if they’ve reliably led to bear markets before. You will find there is no fundamental indicator on its own, no technical indicator on its own, no single silver bullet, no nothing on its own perfectly predicting when a bear market will start. Nor can you have a “feeling” indicating when you should get out. I hear from far too many investors (even professionals) they “have a funny feeling” about the market going one direction or the other they “can’t explain,” but they “just know.” That’s TGH. If it isn’t, take an aspirin and an antacid and get over it. Then take Question Three for this one because that’s what you really need. If you believe you’ve been right about a “funny feeling” in the past, you may have been. Luck happens. But you’re also suffering hindsight bias and forgetting times you had “funny feelings” that were completely wrong.

Osama Bin Laden, Katrina and Foghorn Leghorn Walk Into a Bar

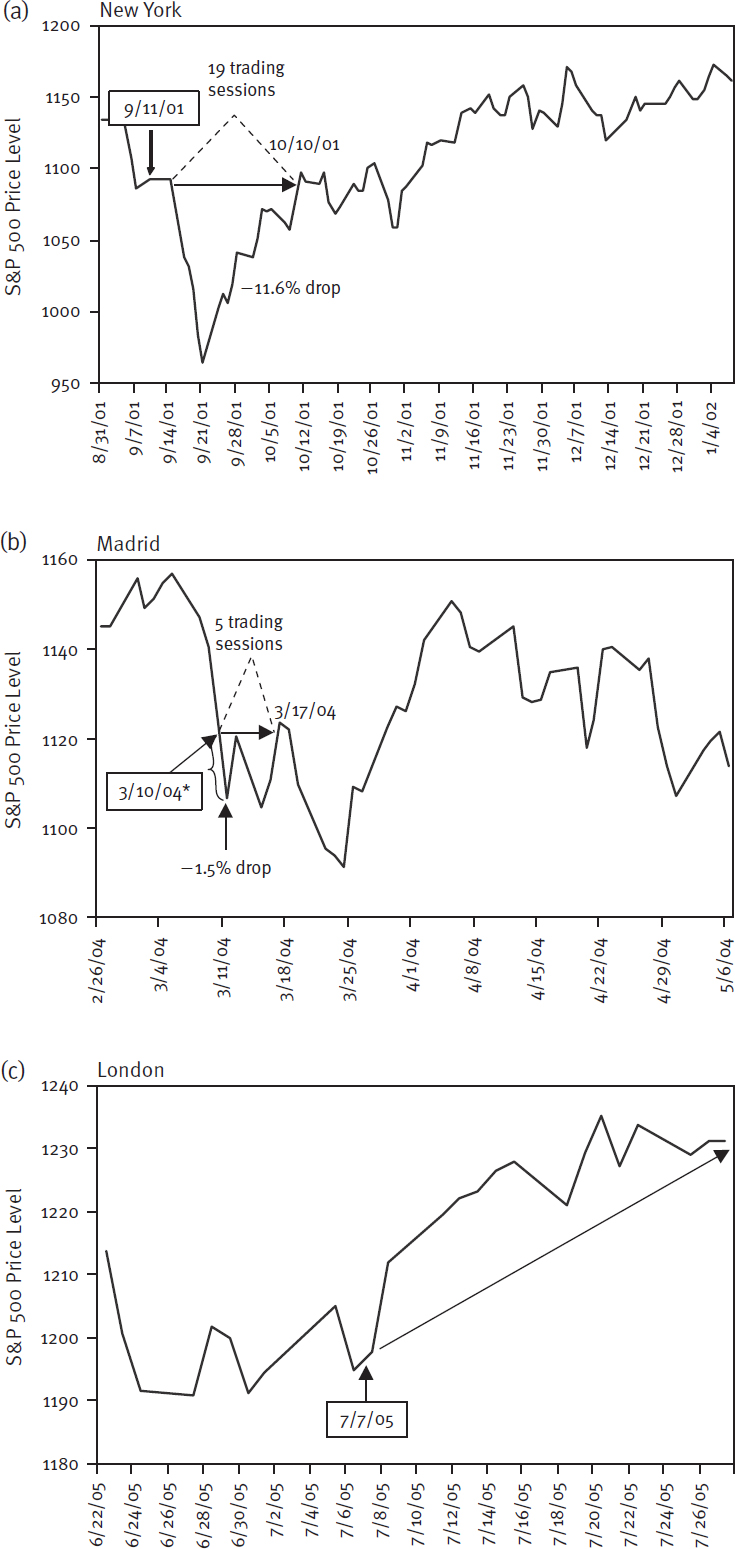

Some may say, “But we live in a different world now. A terrorist attack would break the market, right?” That’s a fair question. The tragic attacks on September 11, 2001, came two-thirds of the way through a material preexisting bear market and a recession—possibly stalling off market resurgence (though we have no way to measure if that’s true or not). So pull a Question One. Is it true September 11 had a lasting, devastating impact on the market?

The US stock market closed that day and stayed closed until September 17 when trading resumed. The S&P 500 nosedived when the market opened—down 11.6% by September 21. 6 But amazingly, in only 19 days, the US market was trading above September 10 levels. And it remained above those levels for months. We remember this differently because long before the attack, the global economy was in a recession and bear market. Did the attack exacerbate the situation? Maybe! But, again, the market retreaded the steep fall and stayed above pre-9/11 levels for months. Note the higher period included all those fears in the fall of 2001 about anthrax. Remember anthrax? The market moved higher right through it without interruption, lifting to prices steadily higher than on September 10.

As always, think globally to see how more recent terrorist attacks on Western nations have impacted the stock market in Figure 8.7.

On March 10, 2004, al Qaeda took credit for a massive train bombing in Madrid. The Spanish referred to the event as “Our 9/11”—a devastating national tragedy. And yet the S&P 500 dropped 1.5% that day and traded at pre-attack levels five trading sessions later. On July 7, 2005, al Qaeda bombed the London Underground, and the S&P 500 was positive that day. The market was indifferent to the attack.

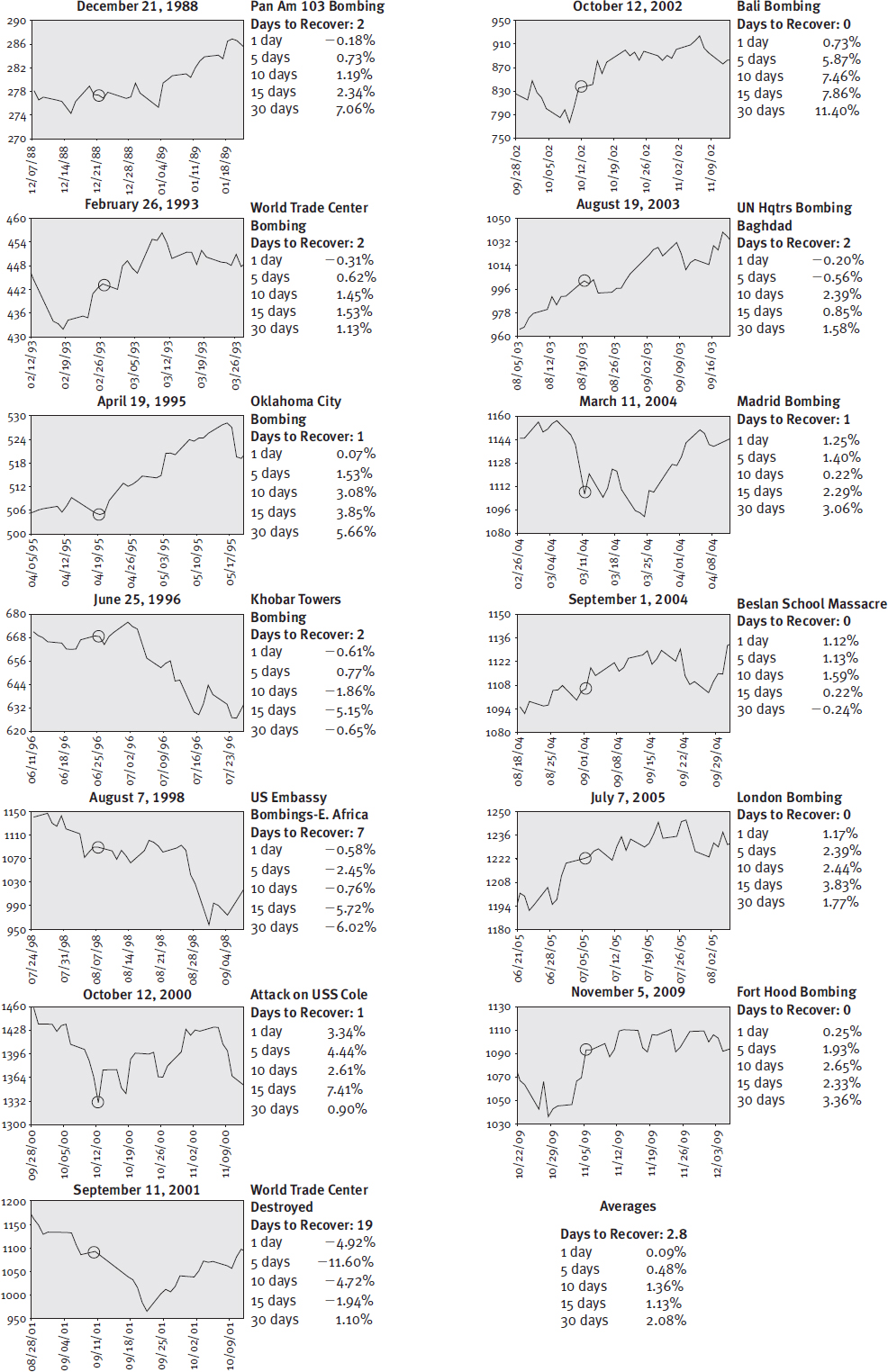

Terror attacks have since continued, and markets largely shrug them off—continuing whatever trend they were on anyway. Whether all future attacks have already been discounted or not is debatable. But since 9/11, there has been no market panic to terror anywhere. How can investors be so blasé about terrorism? This is a new, terrible and very real threat to us wherever we live, work, travel and defend ourselves and our friends. Or is it? We have had previous terror attacks here in the US and on US interests. There was the USS Cole bombing in 2000. And the Khobar Towers were bombed in 1996. And that first attack on the Twin Towers in 1993. And the attack on the Marine barracks in Lebanon in 1983. And Pan Am Flight 103. And the entire history of Israel. And the Irish Republican Army in Britain. The British lived with terrorism on their soil seemingly forever, and their markets did fine then. World War I was sparked by a terrorist act. There were the Barbary pirates and Tripoli. You get what I am saying. Terrorism isn’t new, devastating as it is at a human level. But we are resilient, and so are our markets. Figure 8.8 shows a number of terror attacks in recent history and the time the markets took to recover.

Figure 8.8 Have No Fear: The Market Doesn’t—Historical Perspective

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., S&P 500 price return.

But would a large terror attack now break the market? First, ask if another terrorist attack would surprise you. You may be more surprised—knock on wood—we’ve yet to experience another major American attack (as of this writing still in 2011). Put yourself back to September 10, 2001. No one fathomed 19 thugs armed only with box cutters would perpetrate a coordinated attack using planes and their passengers as bombs. That what happened would happen seemed unthinkable.

Today, it would take a lot to have a major market-moving surprise—and even the biggest terror attack in recent history had limited direct market impact.

What If They Destroyed a Major American City?

What if terrorists destroyed a major American city? Certainly, that would be terrible. But how big would the market impact be? Again, it might be less than you might think, and the way you know is partly by looking at the market impact of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans.

In 2005, New Orleans and parts of the Gulf Coast were obliterated by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Much of the Gulf of Mexico’s oil-refining capability came to a screeching halt. Hundreds of thousands in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi were homeless or displaced. Businesses closed; employees were jobless. And yet the day Katrina hit Louisiana, August 29, 2005, the market rose 0.6%.7 A pretty normal day given the flooding and ensuing chaos. And GDP growth for Q4 2005 was 2.1%, and the S&P 500 was up 2.1%. 8 Not blow-your-socks-off growth, but not the economic Armageddon many pundits predicted. Think about it this way: US stocks were up 2.1% in Q4 2005, and global stocks were up 3.1%—so the US market, even post-Katrina, was not too far off from the world.9 Of course, maybe stocks would have risen more without Katrina. But who can prove that?

Yet, shouldn’t GDP have been hurt hugely based on work stoppage and disruption of refining in the Gulf? New Orleans was decimated. That is a great Question Two to explore. Let’s flip this one on its head: Why shouldn’t GDP and stock returns be healthy following such a major natural disaster? Scale it, like always!

Suppose every person in Louisiana was suddenly unemployed after the two storms. Didn’t happen, but suppose the worst-case scenario. There are 4.5 million Louisianans. Louisiana’s income per capita is historically only about three-fourths as high as America’s average.10 So think about the population of Louisiana instead as about 1% of the United States’ population. If every single person in the state of Louisiana stopped contributing to GDP as a result of the hurricanes, GDP growth would have been shaved by about 1%, one time. For one year, instead of maybe 4% growth, we would have gotten 3%, then moved on normally.

I don’t mean to say Louisianans aren’t productive people and important—but you shouldn’t be surprised there was little impact on the overall economy’s growth. America is huge. Louisiana is too small to impact America’s GDP much. Then remember it’s a global market and global economy, and America is only 23% of global GDP, so the impact on global growth would be smaller still. 11 Simple scaling.

Remember Grampa Fisher?

We also have history to use conveniently. The first thing I did when Katrina struck was pull out my stock charts and history books to remind myself of the natural disaster that devastated my hometown. When the 1906 fire and earthquake leveled San Francisco on April 18, 1906, little was left. Grampa Fisher (see Chapter 5) had to put off his wedding to my grandmother until later that year. They and their families lived with most of the rest of the city in tent camps in Golden Gate Park. My grandfather’s medical practice was on hold for months as he devoted himself to pro bono work for those injured by the tragedy.

But the market didn’t buckle. The US market dropped a hair in April, which might have happened anyway and might have been caused by other things (I don’t really know) but was higher again in May and June and didn’t implode that year. The major buckle was the next year, 1907, with a New York–based banking panic and the market dropping 49%, peak to trough.12 But San Francisco in 1906 was more important to America than New Orleans in 2005. San Francisco’s demise not causing the market to implode in 1906 was a pretty good guideline from history to tell you not to worry about Katrina too much from a stock market perspective. And to tell you not to worry about markets too much if the terrorists, heaven forbid, ever do succeed at causing real havoc in an American city.

You can use the Questions and this methodology to attack other presumably “bearish” events, such as outbreaks of SARS, the bird flu, Ebola, hanta virus, anthrax, chicken pox, etc. Just as SARS was a big 2003 health scare (now long forgotten), in 2005 and 2006, concerns about bird flu morphing to a human-transmittable form were rampant—and again, markets were fine.

Use your Questions to test if any geopolitical event, natural disaster, health crisis, anything we all worry about, plan for, fret about and hear on the news is inherently likely to move the market materially. You will find none of these events is a silver bullet for predicting bear markets.

Now that you have Question Three tools for recognizing the likely direction of the market and can understand what a real bear market does (and doesn’t) generally look like, you are ready to build a real strategy to serve you your entire life. Read on.

Notes

1. Global Financial Data, Inc., as of 02/12/2012. The annualized average total return of the S&P 500 Index from 12/31/1925 to 12/31/2011 is 9.7%.

2. Michael J. Mandel, “The New Economy,” BusinessWeek, (January 31, 2000).

3. Standard & Poor’s Research Insight, top 30 stocks by market capitalization of the S&P 500 Index.

4. Global Financial Data, Inc., Nasdaq Composite Index price return and S&P 500 total return.

5. Global Financial Data, Inc., S&P 500 total return from 12/31/1925 to 12/31/2010.

6. Global Financial Data, Inc.

7. Global Financial Data, Inc., S&P 500 total return.

8. US Bureau of Economic Analysis; Thomson Reuters, S&P 500 total returns and MSCI World Index net returns from 09/30/2005 to 12/31/2005.

9. Thomson Reuters, MSCI World net return.

10. US Census Bureau, “State & County QuickFacts: Louisiana,” http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/22000.html.

11. Bloomberg Finance, L.P., US GDP as of 12/31/2011.

12. Ned Davis Research, Inc., return on Dow Jones Industrial Average.