CHAPTER 1

What Are You Thinking?

Executive presence begins in your head. It resides in how you think about yourself, your abilities, your environment, and your potential.

Nearly everyone has an excellent presence; it may simply manifest itself in another part of your life. Perhaps you are charismatic and confident as your son’s baseball coach, or you are empathetic and inspiring to your best friend. You give a bang-up speech at your college friend’s 40th birthday party, or have just the right words to encourage your sister.

Most of what you need is right there in you, waiting to be tapped for your professional life.

Intentionality is the driver of presence. All the communication tips in the world won’t make up for your thought patterns.

If you are concerned that having executive presence means faking it, consider yourself reassured. The kind of presence that attracts other people to you, makes your team want to move mountains for you, and propels you ahead is the opposite of fake. It is pure authenticity—being more of the person you already are, without the mental subterfuge that gets in the way.

I-Presence starts with “intentional” presence, because it is the driver. There are no tips or tricks that will make up for a lack of intentionality. In fact, sometimes tips can make things worse. Many executives, fresh from tip-laden training in public speaking, find themselves even more nervous and less authentic than before because it feels forced. They have all the same feelings and anxieties about speech giving, but now they are also trying to remember to stand this way or gesticulate that way. You can buy an expensive car with all the latest features and a GPS, but if you don’t know the address of your destination, you won’t get where you want to go.

You need to pick up the right intentions and let go of what’s in the way.

Intentional Is as Intentional Is Perceived

You may be thinking, “Isn’t every functioning professional intentional? If I weren’t, I couldn’t keep my job.” Well, yes, you’re right. And I bet you can point to many times in your day when you aren’t as thoughtful about your actions as you could be—especially as it relates to your presence. And we can easily call out this tendency in other people, too.

Let me take a moment to describe what I mean by being intentional: I define having an intentional presence as understanding how you want to be perceived and subsequently communicating in a manner so that you will be perceived the way you want. It means aligning your thoughts with your words and actions. And it requires a keen understanding of your true, authentic self, as well as your impact on others.

There are different kinds of intentions. Some are broad and relatively stable, such as when you declare, “I want to be a visionary leader.” Other intentions are situational, such as, “In this strategy session, I must be the catalyst for change.” We’ll discuss various types of intentions in the chapters in Part 1, and how to put them into practice in your life.

Trust that intentions change your presence. I see it every day. You will, too.

You Are What You Think, Even When

You’re Not Paying Attention

In January 2001, Harvard Business Review featured an article by Jim Loehr and Tony Schwartz labeling today’s executives as corporate athletes.1 The article addressed how to bring an athletic training methodology to the development of leaders. This approach makes tremendous sense on a number of levels, and especially in terms of mental conditioning.

Anyone who follows sports knows the importance of an athlete’s focus. We all admired Michael Phelps at the Beijing 2008 Olympics as he listened to his iPod stone-faced, concentrating, before he dove into the water. We respect an athlete’s ability to use positive visualization and intention, and readily acknowledge its benefit.

Somehow, though, outside of athletics such rituals seem unnecessary or even silly. It reminds us of Al Franken’s famous Saturday Night Live character Stuart Smalley saying to himself in the mirror, “I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me.” Taking the time to have the discussion with yourself about what you want to accomplish with your presence may seem more like pop psychology/self-help than hard-core executive training.

Guess again. Taking the time to figure out what you want your presence to convey is a critical and powerful first step. That is the image of yourself you want to keep in mind as you do your own dive into the water. It’s your mental aim.

The Wrong Internal Conversation: Why I’m a

Disaster at Golf (and You Might Be, Too)

As you develop your mental aim, you also need to determine what conversation is currently in your head and how it may need to change. Even when you aren’t paying attention, your internal conversation is always happening.

Scott Eblin, author of The Next Level, convincingly describes intention as a “swing thought,” likening it to the last thing golfers think before their club strikes the ball.2 (Eblin is a coaching colleague from Georgetown, and I have to thank him for the original comparison of intention to athletic focus—a common reference that’s helpful for so many people to think about.)

For anyone who has played golf, you readily get the swing-thought idea. And even if you haven’t, you can probably understand how hitting that tiny ball dead-solid perfect requires a whole lot of mental focus. It’s the make-or-break factor.

When I was in my early thirties, I decided to learn golf. I took lessons, got the right clubs, and practiced diligently. At the driving range with the pro, I wasn’t half bad. However, I was terrible when I got on the course. Competitive and averse to failure, I was self-conscious about how I played compared to others around me. I’d choke when I got to the tee and have an all-around miserable game. When I was paired with other golfers, it got even worse. Still I kept trying, remaining furious at myself for hitting well in practice and then falling apart on the course. After a few years with no improvement, I gave it up.

My golf-playing days were before I was a coach. At the time, I didn’t have the ability to fully understand what was happening. When I got up to the tee, my swing thought was literally, “Don’t embarrass yourself.” Is it any wonder that I was such a disaster?

Negative swing thoughts are alive and well off the golf course. I hear them from clients all the time, either stated or unstated. They include:

— I can’t speak in public.

— I’m not a people person.

— I’ll appear self-promoting.

— I’m an introvert and can’t network well.

— I’m just not good in these situations.

— I don’t have what it takes to play the office politics game.

Any of these pretexts sound familiar? If this is where you are placing your mental focus, you can bet it’s showing up in your presence, and maybe even screaming.

Neuroleadership is discussed in-depth in Chapter 9. One of the main findings of those studying in this field is that our intentions actually shape how the human brain functions. The intentions that we hold in our head, either positive or negative, create mental shortcuts that become a veritable path of least resistance. The more we think something, the easier it is for our mind to process it. That’s why it’s critical to be fully aware of any negative thoughts blocking your progress. I’ve included an exercise (see sidebar) to help you “uncover your negative thoughts.”

The intentions we hold in our head create mental shortcuts that become a path of least resistance.

Uncover Your Negative Thoughts

Find a quiet space to contemplate what you believe to be true about your presence. Write down any negative thoughts that may hold you back.

• What do you currently think about your own executive presence and your ability to affect it?

• What assumption of yours is getting in the way or holding you back, and why? How long have you felt this about yourself?

• Try on the idea that you already possess the presence you seek in the various areas of your life. What’s your reaction?

Knowing what our limiting thoughts are, and replacing them intentionally, is the only way to create a different possibility. Eventually, the possibility becomes the new and improved shortcut.

How Intention Plays in the Course of Work

A few years ago, I was coaching Alan S., a senior executive at a Fortune 500 finance company. He was frustrated because he felt that with his experience and background, he should be perceived as a high-performer with the C-suite in his grasp. Yet he was passed over for a promotion. Believing his communication style might be to blame, Alan hired me as his executive coach to work on it.

As I do with most engagements, I started out by speaking with Alan’s colleagues to get an accurate picture of how he was perceived by other people. (See Chapter 4 for how to conduct your own presence audit.) Their take was that Alan was rarely positive about other people’s suggestions. They felt that since he was overly critical, it was best to avoid him. He had great skills, they said, but it was easier to stay clear of him than to solicit his help. Who had the time in a busy day to be dragged down?

At first, Alan bristled at this feedback. He thought of himself as a pragmatist, but overall a positive person. After we delved into his thinking patterns, it became clear that more often than not, his pragmatism caused him to look for what could go wrong in a situation. Only after debunking every negative would he entertain any positive. We also assessed situations where he had face time with his colleagues and corporate officers: executive team meetings. Because there were so many voices competing during meetings, he tended to hang in the back of the room because he didn’t see his contribution as additive (pragmatism again). When I asked what his thoughts were in the meetings, he realized his internal dialogue was, “Don’t say anything stupid.” Sometimes he even scowled without knowing it, either in reaction to a comment or his own thoughts.

Not surprisingly, Alan was unintentionally making an impression, even though he believed that being in the background would keep him from making one. As I came to learn, he was actually a very caring person, but most of his colleagues didn’t venture close enough to learn that about him.

After diagnosing what wasn’t working, we began to create some new intentions that felt right to Alan. To develop them, we looked at leaders he respected and wanted to emulate, both inside the company and in his personal life. He stated a personal intention that he wanted to be seen as capable, positive, and helpful—someone his colleagues actively sought out. Next, we began determining when his stated intention counteracted his actions. One was obvious: He needed to smile more. He also made a conscious decision to hold back reservations when others brought ideas to him; in fact, he would even encourage what was good about their suggestions. He began to drop by people’s offices, just to talk or offer help. And he completely changed his role in executive team meetings by sitting near the middle of the room and making a point to contribute something encouraging in every session.

An intentional presence creates the desired emotional reaction in others.

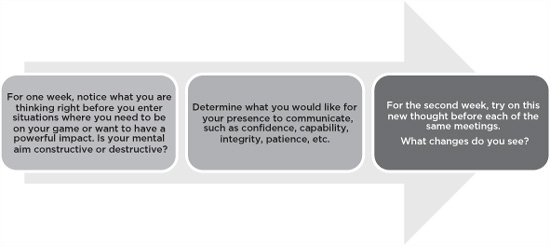

We used the exercise shown in Figure 1-1 to recognize and change Alan’s intentions. This may be a good starting point for you as well to begin noticing how intention plays in your life.

Figure 1-1. Exercise to Observe Intention.

Great Intentions Create Great Reactions

Executive presence at its core is about creating an impression on others. You want your presence to propel you ahead in your work life by getting your desired reaction. Every day is a bombardment of opportunities to persuade, influence, motivate, attract, or inspire others.

Being intentional about your presence means that you must play in the realm of emotions. Humans are emotional beings, and we process information on emotional terms. Think about how you take in the presence of other people. They create an emotional reaction in you. It could be comfort, disdain, fear, excitement, or curiosity. If you think of your favorite boss or leader, you are very likely to conjure up emotional terms to describe that person.

With your presence, you are trying to marry your intent with another person’s perception. This is where authenticity plays a big role. It’s nearly impossible to make another person feel excitement, for example, if you aren’t excited; likewise, you won’t bring out someone else’s confidence if you aren’t confident. (Many of us have endured enough halfhearted corporate pep rallies to know how in-authentic they are.)

The Story of Steve and Stan: An Internet Sensation

Macworld 2007, the huge conference for Apple computer and electronics devotees, provides a perfect example and an unexpected cautionary tale of a missed intention.

Each year, Macworld draws about 20,000 attendees fiercely devoted to all things Apple and immersed in its unique culture set by CEO Steve Jobs. It’s also where Jobs delivers the keynote debuting new Apple products and creating multimillion-dollar buzz overnight. Jobs is known for his electric presenting style. He takes the stage with a mix of humor, excitement, authenticity, and just the right touch of mischief. I’ve seen him onstage. In his trademark black turtleneck, jeans, and sneakers, he looks casual and relaxed. He talks to the audience as if they are old friends swapping stories. You can sense the energy in the room lift when he walks in. The audience can’t wait to be inspired by the visionary Steve Jobs. (As of the writing of this book, Jobs is out on medical leave battling serious illness. Despite that, he took the stage to announce the latest iCloud® offering, as the demand for his presence is that strong.)

Often, Jobs has other CEOs from partner companies join him onstage. They know what the audience expects. They match his enthusiastic tone and casual dress and understand that it’s their job to keep up the energy level. After all, part of Macworld is the experience of being caught up in—and identifying with—the excitement of the Apple brand. Apple equals cutting edge, and you’re cutting edge for being there.

A funny thing happened in 2007, the year Jobs revealed the first-generation iPhone with Apple’s distribution partner AT&T. As usual, Jobs was magnetic. Unveiling the iPhone to a hushed crowd, he garnered cheers as he described the functionality. The crowd was ripe for more. Jobs introduced Stan Sigman, then CEO of Cingular, AT&T’s wireless division. When Sigman came onstage, it was apparent that he looked different: He was dressed in a polished suit more appropriate for a boardroom than this conference hall with a rowdy crowd at Macworld. Still, the audience gave him the benefit of the doubt as he spoke enthusiastically, from the heart, about the first time he saw the iPhone prototypes.

Then it all fell apart. Sigman reached in his pocket, brought out cue cards, and proceeded to read for seven of the longest minutes in the history of Macworld. His comments were disconnected and uninspired, sounding as though they came straight from the boilerplate of an AT&T press release. He looked physically stiff and uncomfortable. While we can’t be sure that he didn’t have an intention for his talk, he certainly didn’t convey one. He overlooked the emotional reaction his presence should have had on the audience, and instead left everyone feeling bored, at best, and at worst, disappointed that Apple had picked such a dull partner.

The Stan Sigman experience became an Internet sensation immediately. Bloggers wrote about it, audience members posted comments, and journalists picked it up. YouTube videos went viral. He became the poster child for poor executive presence.

I show this video frequently in workshops where people are stunned that someone at Stan Sigman’s level would present so badly. But it is about more than presentation skills. Sigman rose through the ranks of telecommunications and built a hugely successful company. He knows how to present. He failed to determine the emotion he wanted to impart and then set the intention that would inspire that emotion in others. His presence should have conveyed excitement, creativity, and innovation. If he had succeeded, 20,000 people would have been a lot happier. It was an anemic beginning, unbefitting a culture-changing product.

Build a Strong Intention (or How to Be More Steve than Stan)

Intention has the power to work for us or against us, so why not cultivate it for good? In this book I discuss cultivating two types of intention:

— Your personal presence brand

— Situational intentions

Taking the time to consider, develop, and use both kinds of intention have far-reaching implications for your presence.

Your Personal Presence Brand: The Big Intention

Your personal presence brand is what you want your presence to convey overall. It shows your core values and beliefs. It reflects your personality. Forward-looking and far-reaching, it is how you aspire to present yourself at work, and potentially in the rest of your life as well. Your personal presence brand is backed by your actions, which I discuss in detail in Chapter 2. Like any brand, your personal presence intention doesn’t change on a whim. It’s relatively static, building over time. Ideally, it’s an internal touchstone, a reminder of how to present the best version of you.

The sidebar “Determine Your Personal Presence Brand” contains an exercise to help you cultivate yours.

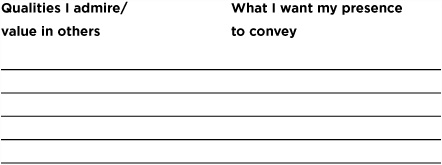

Determine Your Personal Presence Brand

1. Fill out the following chart. Start with whichever column is easiest or go back and forth as necessary.

2. Look at the column of qualities you want to convey and condense or rank them into a top 5 list.

3. Reflect on your list. What do these qualities have in common? Try to create a sound bite, acronym, or archetype for these qualities. For example, “Jack Welch of the education industry.” Also abbreviate as much as possible: “Credible and Compelling; Visionary and Vocal—C2V2,” or “Catalyst for innovation—CFI,” or “Pinch hitter for critical programs.” It can be anything you can keep in your thoughts—all that matters is that it has meaning and resonance for you.

Once you have your personal presence brand figured out, keep it top of mind. Post it on your desk or on your computer desktop if that helps. Return to it at times when you need to communicate strategically, exhibit presence, or even make an important decision. It is an always-available reminder of what you want to reinforce about yourself to others.

Your Situational Intention: “In the Moment” Calibrations

So, your personal presence brand—and the intentions that drive it—remains steady. But you are constantly calibrating your situational intentions depending on the circumstances at hand. And while situational intentions should build and never detract from your personal presence brand, different situations require different actions. A leader’s personal presence brand may be “inspirational visionary,” but that’s going to be applied differently in a sales pitch than in a corporate meeting to announce a restructuring.

Your situational intention is about creating a desired impact. Rarely is it a one-size-fits-all scenario. I mentioned that people process information and events in emotional terms, and often this is a good place to focus your situational intention. Consider what emotion you want to invoke in your audience and you are generally close, if not spot on, to what your intention should be.

Craft a Situational Intention

Before your next communications event, answer these questions:

1. How do you want your audience to feel about this exchange?

2. What emotion do you need to embody?

The answers to these two questions outline your situational intention. (Hint: Because you need to embody what you want to impart, the answers are generally the same.)

The exercise I’ve outlined in the sidebar “Craft a Situational Intention” isn’t the only approach that will work, but it is one of the most effective. Again, just as in the personal presence brand, it is less about specific verbiage or semantics and more about what creates the mind frame for you. A former workshop participant of mine once told me that she’d applied a situational intention of “We deserve to win!” and landed a multimillion-dollar client. You can’t argue with that!

Now Try This: The Intentionality Frame

Typically, employees are most likely to interact with leaders at meetings. Meetings are, in fact, a fertile training ground to learn to use intentions effectively. And because of the repeated exposure (most meetings occur on a regular basis), the rewards are huge.

The types of meetings you attend (e.g., small groups, board meetings, sales calls) may be different depending on your position, but the dynamics are the same. Many of us overlook the importance of meetings. Some of us even approach them with disdain because they get in the way of “real” work. Actually, meetings are your best chance to make a positive impression on others. Learning how to contribute effectively, manage your points adeptly, and display confidence are part of moving up the ranks of any company. Careers are made (and waylaid) from interactions in meetings.

For many executives, meetings are also the places where important ideas are communicated and where other people assess their thought patterns and strategic ability. All eyes are watching—and determining what the person speaking is made of. Here’s a tool called the Intentionality Frame to help you align your intentions to your contributions in meetings. The Intentionality Frame can be adapted to practically any situation.

Let’s say, for example, that you need to have a meeting with an underperforming team that you supervise. You want to learn the root cause of the performance problem so that you can correct the issue. It helps if you have a personal presence brand you can reflect upon first. Then you know to set a situational intention for how you want to come across and what your presence needs to convey. For the sake of this discussion, let’s make your situational intention “gravity with openness.” Your situational intention goes in the center of the frame, as shown in Figure 1-2. Normally when we assemble the points we want to make, we do it either in our head or in a vertical list. Instead, use the Intentionality Frame to make your points along the outer edge of the frame. If your intention is gravity with openness, your points around the frame might be (1) there’s a clear issue though the cause is uncertain, (2) let’s focus on solutions rather than blame, (3) it’s important for everyone to commit to change from this meeting … and so on as you go around the frame. When you use this tool, your points stay in greater alignment with your intention. It’s a visual trick—a mental reminder—to communicate your intention. You can also see that if your initial reaction were to start with some version of “If you don’t improve performance, there’ll be serious consequences,” it would not support your intention. That’s too heavy on gravity with no room for openness

Figure 1-2. Intentionality Frame.

I often use the Intentionality Frame to help people have tough conversations. I start by having them write lists of points they want to make to the other person. Then they apply the Intentionality Frame. It’s always amazing to me how much their points change! That’s why this tool is useful for keeping conversations focused, on track, and close to the goal. Again, it demonstrates the power of intentions.

Meetings are a fertile training ground for trying intentional communications.

The Intentionality Frame can be used for public speaking, executive briefings, one-on-ones, and sales meetings—virtually any type of human interaction.

You’ve Got the Power of Intention, Now Use It

You started this book with an idea that you wanted to strengthen your executive presence. After reading this chapter, hopefully you are beginning to see how negative thoughts can hold you back and how setting a positive intention enhances your presence. It’s a mental game, but as with any game, it takes practice. Ideally, you will have a consistent and overarching intention for your leadership style, as well as an ability to create situational intentions. It’s critical to stop, determine the reaction you want to elicit, and set the right intention. In the next chapter we’ll discuss how to support your intention through your body language and actions.

Key Takeaways from Chapter 1

1. Being intentional about your presence is similar to having an athlete’s mental focus.

2. Uncover any negative thoughts you have about your presence that are getting in your way. Know what’s playing just below your consciousness.

3. Set a positive intention for the kind of presence you want to convey overall. That’s your personal presence brand. For inspiration, consider what leaders had an influence on you.

4. Set unique intentions for situations where you interact with others. Your intention should match the desired reaction from others, usually in emotional terms.

5. Use meetings as an effective training ground for establishing an intentional executive presence.

Ideas I Want to Try from Chapter 1: