CHAPTER 7

What You Can Learn About

Emotional Intelligence While

Riding in the Elevator

Imagine you’re at work, running to catch the elevator. It opens, and as the doors peel back you see that one of the top leaders at your company is already inside. You could experience either of the following reactions:

Oh crap, why didn’t I push the button a few seconds later? It’s going to be a painful ride filled with heavy silences wedged between awkward small talk.

Or:

Cool! I get to catch up and hear what’s going on, from a company leader.

Most of us can relate to this type of experience. What accounts for the difference between the two scenarios, one cringe-worthy and one welcome? You might think the answer is the leader’s basic social skills, and it’s true, those certainly would help make for a more enjoyable ride with almost anyone in a 4-by-6-foot box. But social skills alone won’t make a person excited to see the company’s leader. I would argue that it is the leader’s emotional intelligence, and more specifically, how connected and empathic the leader is, that makes all the difference between the responses.

Of course, another question to consider is: What’s it like to ride an elevator with you as the leader?

The elevator example illustrates the distance that people can feel from their leaders. Some leaders feel very “other” to us, while some find a way to express commonality and sameness. It’s not about being friends with direct reports, or being the person everyone wants at the party. Many leaders don’t aspire to be the boss everyone socializes with after work. (Of course, some do, and that’s fine as well.) The point isn’t to become friends; it’s to bridge the distance by making others feel comfortable enough to speak truthfully to you, and to feel a connection with you. The alternative? Discomfort leads to disconnection leads to disaffection. Not so good.

Empathy: The Killer App in Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence is defined by John D. Mayer and Peter Salovey, two of the leading researchers on the topic, as “the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions.”1 In our discussion of presence, leaders can go a long way toward emotional intelligence by simply understanding those around them better. Empathy, as the saying goes, is “the killer app.”

In creating authentic connections, trust and empathy go hand in hand. If we don’t feel that someone understands us, we are unlikely to forge a strong bond. In corporate America, the idea of the empathic leader has become a cultural prototype to which managers aspire. The theory that emotional intelligence, including empathy, is more important to leadership success than is intellectual acumen is widely accepted. In nearly every company, you can hear the term bandied about. “So and so lacks emotional intelligence” or “We don’t have emotionally intelligent leadership here.” We have Harvard-trained psychologist and former New York Times science journalist Daniel Goleman to thank for that. His mega successful 1996 book, Emotional Intelligence, and multiple bestselling follow-ups, showed through extensive research that empathy is positively related to business success.2

While Goleman may have made the concept of emotional intelligence famous, it was a much lesser known psychologist named Dr. Reuven Bar-On who did the heavy lifting scientifically around the concept a decade earlier. Starting in the 1980s, Dr. Bar-On began studying a person’s emotional quotient, or EQ. Eventually, he developed a statistically valid assessment tool called the BarOn EQ-i.3 The EQ-i test (Emotional Quotient Inventory) has been taken by tens of thousands of leaders in nearly 40 countries to study characteristics that include empathy and interpersonal skills, as well as other factors such as adaptability, stress tolerance, and self-awareness. As a coach certified to administer the assessment, I believe that the findings can be powerful because the qualities measured are recognized to be vitally important. Who doesn’t want to be more emotionally intelligent? These days it’s hard to argue that empathy and connection aren’t critical for leadership.

These are seminal leadership concepts, but I’m not going to use this book to sell you on the idea that emotional intelligence and social acumen are important to presence. I’m going to guess that by picking up this book (not to mention reading this far into it) you are already in that camp. I’d rather use this chapter to discuss what happens in real life between what we know we should do and what we actually do, or what we feel and what we express.

Most people agree that empathy is a valuable trait for leaders, but struggle with how to express it.

Empathy often falls directly through this knowing-doing gap. This chapter is about how to tap into your authentic empathic self and show it to others in the workplace in a way that enhances your presence and increases connection. When you break it down, it’s simpler than you may think. Yet, it’s a struggle for most of us, especially as leaders. As with so many other things, it’s all in the execution.

Either Work Is Filled with Sociopaths or Empathy Is Hard to Communicate

On the one hand, the role of empathy in the workplace is so obvious it’s comical. Of course it’s important to have empathy! Unless you are born with sociopathic tendencies, you have natural empathy for others around you. It makes good sense that we relate better on a human level if we express empathy. On the other hand, in the leadership realm, expressing empathy in a company, on a team, or as part of a cross-functional project is fraught with difficulty. The lines are suddenly blurred between being understanding and being taken advantage of. We get hung up on how much emotional distance we should keep—how much we can invest personally without being sucked in. Sometimes it’s just easier to be squarely dispassionate.

Leaders hold back expressing empathy for fear of being sucked in or taken advantage of.

Recently, I was speaking to a group of business owners about lessons learned in my work coaching CEOs. One of my points was that communicating respectfully to employees requires a CEO to manage his own emotional reactions. In the rush to market, equanimity may be sorely lacking in upstart companies. Employees need to feel that they’ll be treated with dignity in order to take risks and perform over time. One example I gave to the business owners: Don’t blast people in meetings for messing up, but handle performance issues in private. This wasn’t groundbreaking content—just a reminder. I got about two-thirds through my point when one of the audience members boisterously offered that he completely disagreed. In his experience having run three companies, he said that people needed to be called out in front of their peers for their poor performance. After all, metrics were metrics. He said this raised the bar for everyone else. In fact, he claimed he used the public lambast strategy frequently as a motivational tool. I attempted to engage on my point and expound upon how his employees might view things, but I could tell by his body language that he wasn’t hearing it. He believed his way was the right way, and that was that.

Your first reaction might be “What a jerk!” I’ll be honest, it crossed my mind, too. (Okay, it more than crossed my mind. It hovered.) But there’s more to it. Having observed both sides of this issue, I can see the interplay. On one side, I’ve been a leader and now sit in intimate talks with other leaders every day. I know that for many leaders, the most vexing, internalized issues are around how to better understand and manage their teams. It’s an omnipresent topic in leadership coaching.

On the other side, I also regularly speak with employees (through the 360-degree process) about how their leaders function. As such, I hear the personal toll it takes on them when they perceive empathy to be absent. They have one foot out the door awaiting the final indignation. They look out for themselves. They aren’t vested.

And I hear the reverse: When employees sense that their leaders get them as people, they’ll forgive quite a bit on the management side. So if leaders feel empathy but employees don’t see it expressed, what gets in the way?

Employees will give more latitude to an empathetic leader.

• Time. By far, time is the biggest culprit. Many leaders would love to understand their teams better or be more personally connected, but they don’t have the time. Reaching out is time-intensive, and it simply falls to the bottom of the executive’s daily list.

• Personal Discomfort. This empathy stuff is on the touchy-feely side of the continuum, and some leaders fear getting into an emotional conversation that’s out of their comfort zone. It’s better never to go near the personal side than to risk taking off someone’s professional mask to find tears underneath. They’re businesspeople, not psychotherapists.

• Short-Term Thinking. Leaders can choose to take an autocratic style that may work well in the short term. They know they’re pushing their people too hard or managing too aggressively, but they plan to do something about it after the next hurdle (or the next one, or the one after that …).

• Accidental Success. I have a sneaking suspicion this was a factor at play with the man in the preceding story. Sometimes leaders accidentally get lucky, at one company or at one time, with a take-no-prisoners management style. I’ve seen this happen with entrepreneurial companies. When employees have a chance at cashing out substantial stock options, they can suck up anything. However, at some point, getting results from treating employees as merely a means to an end will reach a point of diminishing returns—and likely sooner than you think.

• Few Open Communication Lines. As discussed in Chapter 5, leaders find themselves distanced from the rest of the company right when they need open communications the most. Leaders need constant data to formulate the “word on the street.” This macrosentiment can be even more helpful than individual comments because it’s broad based and less biased. When communication lines are closed, leaders don’t know where to get accurate information if they want it, and no one is offering it up. If you are a leader, you need to hear straight from others what it’s like to work for you.

There’s More Than One Way to Empathize

For some, the phrase empathic leadership evokes images of group hugs, shared tears, and endless team-building sessions. Empathetic leaders might even seem like pushovers, or less ambitious. But if you’ve been lucky enough to work for an empathic leader, you know that they rarely come in this mold. In fact, they come in various shapes and sizes—just like anybody else. Only you can create the leadership style that fits your authentic self. Consider a few different styles of empathic leaders:

The Coach shows empathy through a mixture of tough love and strong support. The coach is not afraid to push you because she sees the best in you. This leader has a good sense of what’s going on in the rest of your life and isn’t afraid to mention it as it relates to your performance and potential.

The Mentor makes you feel that your success is always top of mind. Mentors have your back to guide you along in your career. They will act as a confidante as you hash through ideas and won’t hold it against you as you iterate. Because they have done well, they operate from a point of helping others do the same.

The Truth Teller believes that you treat employees as adults and free agents who have a right to hear it straight. The truth teller doesn’t sugarcoat as a matter of principle and can be counted on to let you know what you are doing well and where you can improve. You always know where you stand.

The Buddy eschews hierarchy as a structural imperative. The buddy seeks to be considered a colleague first and foremost. He’s someone who stays in the trenches to keep a bead on the team, operating from the idea that “we’re all in it together.” The buddy leader frequently socializes with the team and can easily approach others with feedback as part of daily interactions.

The Relater has an intuitive ability to grasp the emotions of others. Whether from personal experience or keen observational skills, relaters tap into the hopes and fears of those around them and relate what they see to their own experience. They are self-revealing through shared stories. Even if you don’t know them personally, you get the feeling that “they get you” in the abstract and that you know what they’re about.

As you read through these prototypes for empathic leadership styles, you probably recognize one of these characteristics, or a blend of them, in yourself or in others. The examples are divergent in their styles, yet all seem like pretty great people to work for. No doubt you gravitate toward some of these leaders more than others, based on your own perspective. We all do.

Only you can create the leadership style that’s authentic to who you are.

The best way to incorporate—and sustain—an empathic leadership style is to do it in a way that’s authentic to you. You don’t have to fit into the touchy-feely mold, or any of those I just described. There’s wide latitude here. Keep an open mind about what empathic leadership means—the ability to understand and relate to the feelings of others—and you may find that there are behaviors that you can adopt quite naturally. One of the best places to start is by modeling the leaders who have inspired you in various aspects of your life.

For me, a resonant example of someone who embodies the exact right mix of empathetic, effective, results-focused leadership is Jim Kaitz, the CEO of the Association for Financial Professionals (AFP). The 15,000-member AFP is best known for its annual conference—billed as the largest annual meeting of corporate treasury and finance professionals in the United States—as well as for being a professional development resource and credentialing body for finance professionals. Since Jim took the helm 10 years ago, he’s been the driving force in expanding the organization from a treasury-focused niche association to a global finance thought-leader, nearly tripling revenue in the process. Some leaders achieve these kinds of results but leave a charred path behind them. Jim’s style is decidedly different. He’s a transformational leader who drives accountability and performance. People who work for Jim know that they need to bring their best to work every day. Jim is diligent and energetic and has a coveted ability to combine big-picture thinking with a clear understanding of the daily execution necessary to achieve it. Jim is not the boss to have if you want to slack off.

At the same time, Jim is one of the warmest and most empathetic human beings I know. He has fierce loyalty from his team, with retention numbers to back it up. I’ve heard from numerous people at AFP over the years that Jim is the reason they’re in the job. Jim cares deeply about his people, and it shows through in everything he does—including being direct and straight with them. He doesn’t placate or coddle; in fact, he’s so transparent that his goals, and the goals of every single person working at AFP, are visible to the entire company. When asked to explain his magic formula, Jim is self-effacing and modest.

“I believe in people and thankfully that comes through,” he explains. “It’s my job to come to work every day and be an advocate to help others achieve a common goal. I inherently believe that people want to do a good job, and why wouldn’t I want them to be successful? I make it clear that we’ll all be held accountable, but at least we’re in it together.”

Jim prioritizes his position as a team champion. He knows that greatness will be accomplished through his ability to win hearts and minds. It’s a role he accepts readily and with intention. “You have to absolutely commit yourself to the people side of this job. You build trust when people see that you genuinely care about them. If you claim to care and it’s not perceived, you’ve lost. You can look people in the eye and say we have to do a better job here when they know you care. Threats never work in the long run.”

Jim believes that empathetic leadership is stable leadership. “I was told a long time ago that I’m predictable, which I take as a compliment. If leaders show volatility and inconsistency people will play it safe around them. I want their best thinking. My team [members] know what they will get from me, even in times of controversy or stress. One of my favorite sayings is that self-awareness is a powerful tool.”

Finally, he reinforces the point made earlier in Chapter 5: Exhibiting weakness alongside strength shows a leader’s humanity and fosters trust. “Having people know who you are as a person is critical,” he says. “You have to bare your soul a bit and be vulnerable or people don’t feel comfortable with you as a person.”

Empathy Outward Requires Empathy Inward

Another part of emotional intelligence that deserves to be discussed alongside empathy is the idea of self-management. On the BarOn EQ-i, it’s discussed as “emotional self-awareness,” or the ability to understand what emotion you are having while you’re experiencing it. This sounds easy enough, except that humans aren’t so good at it. We can be angry and not even know it until someone else calls us on it. Only then do we realize, hey, I am ticked off at what my coworker said yesterday. And sometimes we displace our emotions. Consider the proverbial “kicking the dog” syndrome.

When we don’t stop to examine the genesis of our feelings, it’s hard to control our impulses. We fly off the handle easily, or without even realizing it we take actions that are out of alignment with our intentions. That’s why before we can express empathy toward others, we first must show it toward ourselves. Otherwise, our own stresses and emotional baggage will drag us down. After all, how can we put ourselves in someone else’s head if we can’t figure out how to manage our own emotions?

Here’s a little background to illustrate this point: It’s a dirty little secret that most entrepreneurs walk around with a hefty, at times crushing, sense of fear. Many businesses are just a few short steps from disaster at any given moment. Products can bomb, employees can sue, customers can refuse to pay, and funding can dry up. In fact, there are so many ways to fail, and fail spectacularly, that I began to see starting a business as the opposite of the easy path to the American Dream. Thankfully, no one figures out how hard it is until they’re in the middle of it, which explains why our entrepreneurial culture continues to flourish.

Fear of failure isn’t even the hardest part. As a business owner, you are personally shouldering an enormous amount of risk. If you have employees, you are personally liable for payroll taxes, retirement savings, and possibly more, depending on how the business is structured. Your personal assets—mostly likely your home—guarantee debt and long-term liabilities. I vividly remember having dinner with a friend who was frustrated about his job and concerned his position might be at risk. “You’re lucky,” he said. “If you mess up, you won’t lose your job.” “No,” I conceded. “But if I mess up, I could lose my business, my house, and lots of other people would lose their jobs.” Touché.

If entrepreneurs can’t learn to manage this fear it will bury them. You can’t sell to new customers or motivate employees from a position of fear. You definitely can’t innovate or encourage outside investment when fear is oozing from your pores. No one’s personal presence intention is “gnawing dread” or “frenzied panic.” Worse, fear is insidious—it masquerades as frustration or anger or stress. It can make you irritable and protective. Your only hope is to label it, make it explicit, and fight it face-to-face. A mentor of mine once told me when I was in a serious place of fear to remember that things are never as good or as bad as they seem. That became my common refrain when circumstances were particularly dicey. Remembering it helped me dampen the fear and regain perspective. It took a conscious effort to force self-reflection to manage the fear, sometimes using the techniques I discussed in Chapter 3 for tackling communications anxiety. It took me a while, but I came to understand that when I reacted so strongly to an issue I needed to take a step back and analyze where my reaction was actually coming from. I’ve spent my career around entrepreneurs, and I know with certainty that it’s the same for most of us. Fear is a constant, and emotional self-awareness is necessary for survival.

And entrepreneurs are not alone. Lots of executives redirect anger, frustration, sadness, or fear without realizing it, undercutting their capability. Tempers flare, turf battles rage, words strike defensive chords, and stress pervades. In this kind of environment, simply knowing what’s actually going on provides a strong defense against unconscious reaction. You can’t manage what you don’t know.

The next time you have an extreme reaction or feel anxiety or stress, ask yourself: What’s that about?

After you answer, ask it again: And what’s that about?

Keep going with the same line of questioning until you arrive at the true emotion underlying your action. Then tackle it.

You may find that when you extend a bit of empathy to yourself, it’s a lot easier to extend it to others as well. At the very least, you’ll have firmer, better-understood emotional ground from which to do the extending. Emotionally intelligent leadership sees destructive emotion for what it is, sets a positive intention, and works toward it.

It’s Easy to Be Heavy, but Hard to Be Light

The author G. K. Chesterton first coined the phrase “It’s easy to be heavy; hard to be light.” I love the resonance for executive presence. Many leaders, and especially new ones, find themselves trying to create some distance from those around them. It’s as if they need to go through a metamorphosis to redefine themselves as elevated versions of their former selves. In this new state, you’ll make sure (in a new, to-be-determined way) that everyone knows who’s boss. It will involve embodying some sort of commanding presence with just the right touch of superior attitude.

A lot of people fall into this trap, especially when promoted in the same organization. I recall talking through this issue with a mentor after I was promoted from team member to team manager. I was telling him all the things I was going to do so that everybody would know I was in charge. He simply said, “Kristi, everybody already knows you’re the boss. You need to focus on how to make your team want you as their leader.”

The distance comes naturally with any leadership position. It happens so quickly it can knock you back a few feet. You don’t have to create it. What you do have to create is the presence to bridge that distance between you, as manager or leader, and others on your team. The individual connection has to be so strong that even as you arrive at a place where you can’t possibly know everyone, everyone still feels as though they know you. I’ve never seen this happen by playing the heavy. It takes the empathy card to go the harder road and play it light.

Tony Hsieh, CEO of the hugely successful online retailer Zappos and a thought-leader on connected leadership, puts it this way: “If you think of the employees and culture as plants growing, I’m not trying to be the biggest plant for them to aspire to. I’m trying to architect the greenhouse where they can all flourish and grow.”4

Become a Commonality-Finding Machine

A conversation I frequently have with clients I coach goes something like this:

Client: I’m having trouble with someone on my team. He’s not performing as I need him to. I’m starting to see some push back and frustration. I need to talk with him, but I want to approach it correctly. What should I do?

Me: What do you know about him? What motivates him?

Client: I’m not sure. He’s hard to talk to. We don’t have much in common. I don’t know him very well. I know he’s from California originally and had a kid last year. That’s about it.

Me: Sounds like you don’t know enough about him to manage him appropriately. Let’s start there.

At the risk of presenting a scenario that seems glaringly obvious, I can’t change the fact that this type of dynamic is common. It happens for all the reasons discussed in this chapter—lack of time, comfort level, or priority. Leaders have to try hard to find connection points and commonalities with their people, or they won’t exist. It won’t happen organically. Distance happens organically. And this information is vital, not only to an empathic leadership style or emotional intelligence but to effective motivation and management.

You can learn about your teams in as many ways as humans can communicate. That’s pretty much why office happy hours and off-site gatherings exist. However, I’m a big fan of the Discovery Lunch. Meals get people out of the stuffy office and into a more relaxed setting. People let their guard down when a meal is shared. Consequently, we’re primed to show a lighter, more personal side of ourselves. As the leader, your job at this lunch is not to discuss work or upcoming projects but to gain a fuller picture of the person sitting in front of you. Similar to the discovery phase in a legal engagement—though in a kinder, gentler fashion—you are finding answers. You can discuss home life, hobbies, anything you want. Just be sure to ask these two questions:

— What do you want for yourself and your career?

— How can I, and your position, help you achieve it?

If you know the answers, then you have potent information to lead another person. You know how to motivate people. You know how to retain them. You know what you can do to increase connection. You create commonality through shared goals.

In the best possible world, you want to start with new hires so that you can set the tone for your leadership style while the person has a fresh perspective. But Discovery Lunches work for existing teams, too. Be forewarned, though: If you spring it on people out of the blue and start asking lots of questions, they might be a teensy put off—and fear something fishy is about to happen. Make an announcement to your full team that you want to catch up with everyone, and that you’ll be scheduling lunches with each person in a certain time frame. Once you initiate the idea, make it a quarterly occurrence.

Let’s go back to that elevator ride. What if the leader knew two or three things he had in common with you? Then, instead of engaging in awkward chitchat, he could mention a sports team you both liked, or remark on the college you attended, or share a skiing story. It would have been a very different elevator ride.

To create connection, leaders need to be commonality-seeking machines. Every interaction is an opportunity to bridge the difference by seeking out areas that create sameness and understanding. Even if you lead a team of thousands of people around the globe, if you use distinct interactions to be inquisitive about others you’ll build that individual connection. It enhances the interpersonal dynamic like nothing else.

The Zero Degrees of Separation Game

Write down the name of each of your direct reports. Can you name two or three things you have in common with them? (Working at the same company doesn’t count! However, if you used to have a similar job to theirs, that does.)

How many people could you easily find common ground with?

For anyone you missed, you know what to ask next time you share an elevator.

The Virtuous Circle of Empathy

For many people, the concept of empathy is clear, but in the moment of an interpersonal exchange or a slight conflict, it becomes elusive. When you are faced with a situation that requires more demonstrable empathy than comes readily to you, it is helpful to have a strategy to fall back on, to prepare for your part in the discussion.

Being more empathetic boils down to being open, listening, and acknowledging what you hear. (For years I searched for something easier so that I might avoid the inevitable question: You mean I have to spend more time listening?) The most admired leadership scholars and authors have all covered it—Peter Drucker, Stephen R. Covey, Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner, Peter Senge—to name but a few.5 The EQ-i emotional intelligence assessment offers an entire development section on ways to listen and acknowledge others in a person’s everyday work life. Nearly every executive communication book I’ve ever read (which is a lot, given my penchant for beating to death any topic I care about) mentions the same empathy strategies. In Leadership Presence, Belle Linda Halpern and Kathy Lubar lay out a straightforward and compelling case for how leaders can use the techniques honed by actors to empathize with anyone through listening, acknowledging, and sharing.6

Empathy gets lost in the heat of the moment.

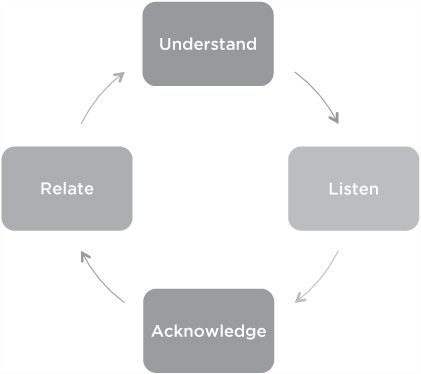

Although the time-honored strategies are the ones that work, many of us have a hard time putting the pieces together in situations where empathic connections are especially critical. I’ve found it can be helpful to view empathic communications as a process. To that end, I use this virtuous circle of empathy, outlined in Figure 7-1, as a model. It can be used for tough conversations with employees, to get to the bottom of derailed projects with colleagues, or to help out a friend. It serves as a reminder to develop an executive presence that others consider open, considerate, and connected. The specific situation is irrelevant.

Figure 7-1. Virtuous circle of empathy.

Let’s examine what the four boxes in Figure 7-1 mean in this context.

Understand

As the jumping-off point, understanding is the willingness to go into the conversation from a position of learning, not of knowing. It is the 5th habit of Stephen Covey’s 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: “Seek first to understand, then to be understood.”7 Your job is to understand everything you can about the person, the situation, the background—everything. Take a step back and ask yourself, “What if this person were me?” At some point, it may have actually been you. Consider yourself an information gatherer and collect feedback on the situation from various angles. Then in the discussion, ask questions of the other person in an attempt to paint a fuller picture. Don’t assume you already see it.

Listen

When you are trained as a coach, you spend a tremendous amount of time learning to listen. I thought I was a fairly good listener beforehand, but it turned out that I had a long way to go. Most of the time, when others speak we only half-listen. The other half of us is listening to the dialogue in our head, which is going over the next question we want to ask, comparing what was said against what we thought would be said, thinking about that conference call we have to jump on next, wondering if our spouse called the plumber. We drift. In fact, we drift a lot. And though we may think we’ve gotten good at disguising it through steady eye contact and reflective head nodding, drift shows.

It takes effort to listen well, but it feels amazing on the receiving end. We feel heard, validated, and supported. We gain clarity from processing our thoughts out loud. There are entire industries, such as coaching and therapy, built around listening because it’s so valued. To truly listen, you must be entirely present and focused on the full measure of the other person. Good listeners:

It takes effort to listen well, but it feels amazing on the receiving end.

— Communicate with only the people in front of them (phones, email, and outside interruptions are ignored).

— Ask questions from a place of genuine curiosity, not to lead the other person to their agenda (accordingly, they use more What or How questions than Why questions).

— Focus on the other person’s answers, not on their own thoughts.

— Probe in areas that seem important to the other person, not necessarily to them (e.g., Tell me more about what concerns you with that …).

— Aren’t worried about being right or having a pithy reply.

— Notice the person’s body language as a form of feedback.

— Observe their own body language to keep an open posture.

— Can take disparate answers and reflect back patterns.

— Are willing to flow with the conversation.

Acknowledge

Acknowledgment means verbalizing that you see the view the other person has from her seat. It’s a validation of another person’s position. Notice I didn’t say that it’s a validation of another person’s position as your position. This is why acknowledgment can be difficult, especially when we patently disagree with the other person’s perspective. Acknowledgment may look like acceptance, but it’s not. Acknowledgment is not agreement. It’s not even close.

Acknowledgment is neither acceptance nor agreement.

It doesn’t take much to show acknowledgment. It simply is letting someone know:

I can see why you would say that …

I understand where you’re coming from …

I get that you are disappointed …

Of all the aspects of the virtuous circle of empathy, acknowledgment has the ability to completely change the conversation. It’s like an “I’m sorry” when you are arguing with a loved one. Everyone takes a deep breath and some steam goes out of the fight. The problem is still discussed, but less confrontationally.

Acknowledgment has the ability to move two people at cross-purposes to the same purpose. It lowers defenses by demonstrating that you understand the other person’s viewpoint. The other person’s opinion is rational and valuable—even if it’s not your own.

Relating is the last and most straightforward stop in the circle. It means comparing another person’s experience to one that you’ve observed. For instance, if you are talking to colleagues about their struggle with a part of their job, you let them know that you’ve had a similar issue in the past—or that you’ve watched a colleague overcome the same thing. It need not be an exact comparison. As a matter of fact, it can be affirming to note that while you don’t have direct experience of the particular situation, you are familiar with similar situations and share a common work ethic or approach. You get the point. By relating, you are bringing yourself into the discussion. Stories are a perfect vehicle to use here. When we relate to someone fully, it reinforces that we know what it feels like to walk in his shoes.

One caveat: While sharing your experiences is important, be mindful not to share too much. You don’t want to hijack the conversation. If the conversation is becoming about you, find a way to steer it back to the other person.

Two Ways Empathic Leadership Plays Out

Demonstrating an empathic leadership style produces positive results in engagement, retention, motivation, and camaraderie. The benefits are hard to exaggerate. However, when situations get tenuous, that’s when connected leadership can draw a line in the sand. Leaders who can bring that individual connection to their teams create transformational outcomes. They save companies, redefine purpose, and change lives. Here are two divergent examples of empathic leadership at work. The venues and the scales vary, yet you can see the virtuous cycle in both.

Example 1: Empathy Creating Possibilities

Kevin, a CEO of a management-consulting firm, was grappling with how to part ways with his managing director, Dana. For the past year, he had tried everything to improve Dana’s performance. After much hand-wringing, he knew that she was simply not right for the job. She had solid skills in key areas, just not the necessary ones for the broad management role he needed filled. The prospect of firing Dana filled Kevin with angst. She was well liked inside the company and had significant industry contacts. For personal and professional reasons, he wanted her to leave on positive terms, and with a soft landing. He knew she couldn’t keep taking a high salary in his company, yet he didn’t know how to encourage her to move on and couldn’t imagine walking her to the door. He was stuck.

We took a walk around the virtuous circle of empathy. Our first stop: understanding. When Kevin thought about Dana outside of his firm, he realized that she was someone who was highly motivated by status and by maintaining a large circle of relationships. She had also shown signs of interest in entrepreneurship, although he had never explored that topic with her. When he began to see a path toward a win-win situation, he prepared for a big conversation with Dana.

When they talked, Kevin acknowledged how she must be feeling, knowing she was not as successful as she wanted to be. He related it to his last job before he started his firm, and how that encouraged him to chart his own course. They listened to each other and spoke unguardedly for two hours. At the end, Dana decided to try to start her own consulting practice with Kevin as her first client. He was happy to oblige.

Example 2: Empathy Creating Hope

While the last example was about empathic leadership on an individual basis, consider the broader-scale case of Fannie Mae. If you have a home mortgage, there’s a good chance that Fannie Mae had a hand in it as a guarantor. For much of its history, Washington, D.C.-based Fannie Mae, with its skyrocketing stock prices and progressive work policies, has been viewed as a model company and a destination workplace.

That all changed abruptly in 2008 when Fannie Mae suddenly became synonymous with the housing crisis and found itself in the thick of a media and political storm. As part of the government’s efforts to stabilize the financial sector, Fannie Mae was placed under conservatorship. Instead of the company’s leadership deciding Fannie’s future, Congress would.

Fannie Mae employees were morally devastated by what had happened. The whole country seemed to be blaming them for the housing market collapse. Every day it seemed the media was conjuring up a new negative spin on Fannie Mae. Personal net worths and retirement savings plummeted with Fannie Mae’s stock prices. Employees went from workplace pride to workplace embarrassment. And worst of all, no one knew what Congress planned to do with the company after the new Obama administration stepped in. People feared for their livelihoods and their futures.8 (As of this writing in 2011, the verdict is still out on Fannie Mae’s precise future.)

In September 2008, Herb Allison was appointed by Fannie Mae’s conservator to step in as the CEO. During his tenure, Allison was a model of what empathic leadership could do. First and foremost, he was a communicator. He made sure everyone across the company—in all locations—knew what the corporate values were. He modeled brave leadership by making tough decisions and taking accountability. He spoke frankly about what he could control and what was out of his hands. He held weekly town hall–style videoconferences where any person could ask any question and he would answer it. People were scared, frustrated, and angry. But having the opportunity to take a question straight to the top every week spoke volumes. Allison showed Fannie’s employees that he knew what they were going through, and that he would go to bat for them and the company. He was inspiring because he reached out, understood, and connected. He had authentic presence. (He was so effective that after only a few months President Obama tapped him to run the Treasury Department’s Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, created to buttress the nation’s financial services industry.)

During this period, you could hear employees from the VP level to the custodial staff commenting that they felt Allison was looking out for them. People who had never laid eyes on him came to work every day feeling that they knew him.

Chris Segall, then director of talent management at Fannie Mae, put it this way: “When Herb spoke, you could hear a pin drop in the room. He projected wisdom, sincerity, and a firm conviction of what was right versus wrong. His capacity for listening to others was equally impressive. Regardless of your level in the company, you had his full attention. He listened as though each word you said mattered and might just contain the next revolutionary idea.”9

Herb Allison’s leadership was a bright light in an otherwise very tough time. He created hope.

It’s a Circle for a Reason

Each time you go around a virtuous circle it gets easier. If you seek to understand, listen, acknowledge, and relate, then you’ll ask better questions, strengthen your connections, and gain a deeper understanding of the situation.

Empathy creates better relationships and more successful outcomes. If there is a relationship that’s weakened, empathy can build more intimacy and enhance overall trust. Think about what’s holding you back. Then, if necessary, take a step out of your comfort zone.

Empathy that stays in your head unexpressed has zero effect.

Here’s the big point for leaders: It’s not enough just to have empathy; you have to show it. We all have empathic thoughts, but just like any killer app, if the idea stays in your head, the world remains unchanged.

Key Takeaways from Chapter 7

1. Most executives have been conditioned to aspire to an empathic leadership style. The breakdown is between knowing and doing.

2. Leaders often cite lack of time, personal discomfort, short-term goals, or a past incident as reasons they fail to get inside the heads of their team members.

3. There are multiple styles in empathic leadership. The stereotype of the group hugger is not the norm. Find a way to apply your authentic self in an empathic way.

4. Become a commonality-seeking machine. Look for authentic connections continuously in your interactions.

5. Creating empathy is a virtuous circle. When you are searching in the moment to truly identify with someone, remember to understand, listen, acknowledge, and relate.

6. It’s not enough to feel empathy—you have to express it. If a tree falls in the forest … you know the rest.

Ideas I Want to Try from Chapter 7: