A great walk and talk

Walk and talks are typical long Steadicam shots. We see them all the time in movies, TV shows, industrials, and commercials. It's the bread and butter shot for Steadicam operators, plowing through pages and pages of dialogue, yet often these shots are very unsatisfying or uninteresting. So what makes a good walk and talk shot? They do exist! What makes for a dull one?

Dramatic tension

Earlier in the book we talked about dancing with the Steadicam and maintaining a tension with the rig. It is important to maintain this tension, this relationship, even when the camera is still. It is similar to the tension that must be maintained between the dancers in a tango, even when the dancers pause. The Steadicam's tension is defined by its weight and mass (it's a very consistent partner!), and we hold a physical relationship to it throughout the shot.

A similar tension or relationship must exist in the scene. In Acting 101, one learns that dramatic tension is created when an actor's intention or goal meets an obstacle. Often the obstacle is another character's intention. If there is dramatic tension, there is usually some physical manifestation; for instance, one actor grabs another and spins her around. Sometimes the battle is more cerebral, with one actor winning an argument, and the physical manifestations are very small, such as a look or a drop in the shoulders, a turn of the head.

If there is dramatic tension, the characters can have a relationship to one another, and then the camera can have a relationship to them. As Steadicam operators, we can dance with the action.

Far too often in walk and talks, the actors walk simply to reach their end marks, an activity without dramatic tension. Moving though space substitutes for real dramatic action. It feels like an important shot and many pages are covered, but it is very dull.

An example

A good walk and talk manages to get the actors to their end marks, cover lots of pages,and use the space without subverting the dramatic action. A brilliant walk and talk shot can be found in Carlito's Way. directed by Brian DePalma and operated by Larry McConkey.

The scene is late in the movie, when Gail (Penelope Ann Miller) says she is late. Carlito (A1 Pacino) has to stop her physically, find out what is going on, prevent her from going to the doctor to end the pregnancy, and get closer to her. She wants to escape, get to the doctor's, keep Carlito in the dark, keep him physically away. There is plenty of dramatic tension here. Who is going to win the battle?

Actors move

Watch the scene several times. Note how the characters use the space, and how they change their relationship to each other. They move toward and away from each other, change their tactics as they hear new information, stop and start again, all in the service of the drama. Add they also get to their end marks.

Move the camera

Watch how Larry's camera moves with them, changes framing to help the dramatic tension (shorting, centering, raking), and starts and stops with the action.

Carlito's Way 1:14:45

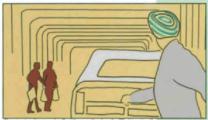

At the beginning, the space between the characters is great, both emotionally and physically. Gail is not only on the far side, but the camera is placed to maximize the separation between the characters. As the characters get closer at the end, notice the subtle push-ins. And Larry arrives at a precise end frame, in sync with the actors. Even the background action is folded into this plan. There is a tailing FBI agent who is carefully revealed and hidden throughout the shot.

A lot of what makes this shot interesting is how the camera reveals the space, and, at the same time, emphasizes the dramatic action. Imagine if the actors had been told to walk side by side, and keep walking until they got to the end marks. What could the camera have done? Not much, and the result might have been okay. Okay, but not brilliant.

Use the space

Look again at the opening frames. Angling the camera off of the line of camera movement (i.e., raking the camera) emphasizes the space between the characters. Remember, raking the camera to the line of movement creates two vanishing points — the “normal one” that the lens points at, and a second point, also called “the appearing point,” that the camera moves away from. The two vanishing points help to create the sensation of three dimensions. At other moments in the shot, the composition is more formal and centered, reflecting a different relationship between the characters.

Stops and starts

Check out the clear, clean and precise stops and starts, all in tune with the action. It all works to emphasize the story. Larry often talks about urging the Steadicam into the proper frame. You can almost feel him slowly shifting the perspective, just barely panning enough to keep Carlito in frame as he comes around Gail. The camera moves just enough to keep up with the action, just enough to get to the right spot to reveal the next story point. Carlito doesn't want to frighten Gail away, and the camera doesn't get too pushy or close either — until the end when Carlito makes his move to get close to her.

Watch this shot again and again, and you will discover even more about great operating.

Watch out

There should be some automatic warning system on your sled that activates sirens, flashes lights, and spews dark smoke out of you monitor when the actors are asked to do a scene in reverse — start at the end marks and walk and talk the scene to discover their starting positions. Then when they walk from this mark, they will end up at their end marks. Clever, right? Not really. The walk becomes all about getting to the end mark, and the biggest physical action the actors have to work with is subverted to this mundane goal.

We know of at least one walk and talk on a high definition TV show that was as long as the crew could wind the fiber optic cables through the set. The cable length determined the start marks, and the result was the same: the walking was for movements sake, unrelated to whatever drama was in the script. Although the operator thought it looked cool and it was fun to do at the time, he now thinks it was pretty unremarkable as a shot.

Without the dramatic tension, the relationship of the camera to the action is arbitrary or patterned: we are stuck maintaining a size, a relationship between foreground and background, holding so many characters in frame, a given raking angle, etc.

So what can an operator do when presented with a big,

let's-plow-through-pages-of-dialogue walk and talk?

Sometimes nothing. Maybe not every shot has to be so well conceived. The old line is that one should not pee on every fireplug. Some moments in the movie are more important and worthy of the time and effort than others. But such an attitude is defeatist -every shot can be interesting and appropriate. There are only a few precious moments to tell this story, so let's make every one count!

Designing a better walk and talk

All too often, you will find yourself consumed with just getting to the end of the shot (like the acton are) and avoiding reflections and lights and tripping over the curb. But if you can, try to suggest camera positions, speed changes, and even stops and starts to emphasize the drama. Suggest that you would love to be in one position to see this moment and in another position to see a different moment. Try to be really, really positive about how you can help what is already in the script and happening with the acting and the location. Try not to wed yourself to one long continuous shot.

Breaking up a long walk and talk

On the set of The Gum I was presented with a long exterior walk and talk shot that started under some elevated subway tracks and ended up several blocks later at an apartment door. During the scout and rehearsal, I began to feel (as did the director and DP) that we did not have the extras and set dressing to fill the entire shot, that there were a couple of dead areas that might be best served by a cut, and that no matter what the camera did, some of the flavor of the new location would be lost if it was all shot on one wide lens.

The Guru 0:31:46 (one shot becomes three, then four)

Director Daisey von Scherler Mayer, DP John de Borman, and A-camera operator Ken Ferris came up with a series of shots to take maximum advantage of the location and production realities. We started the sequence with the A-camera. We used an extreme telephoto shot and a sliding dolly move to introduce the neighborhood and emphasize the graphic shadows from the train tracks. This shot was followed by two shorter Steadicam shots.

This approach allowed us to time the shots to have a train in frame at one point, concentrate our extras and set dressing, and give the actors a chance to get each part of the dialogue right and to alter their physical action. It also saved my legs, so I could concentrate on getting good framing, rather than just trying to get from the beginning to the end of a long shot.

In the final cut, the editor split the first shot in two. No one watching the movie seemed upset that we used four shots instead of one.

Make a plan, make it happen

It's really tricky to assert oneself creatively and change the plan at the last moment. The sooner one has the conversations, the easier it is on production to alter the big plan. Some people will like your making suggestions, others will not. Be sensitive to the people and the situation you find yourself in. Ask for help from the director and the actors to improve your relationship to the action.

The major key to creating better walk and talks is tuning in to the dramatic action. Read the script, listen to the director, and watch the actors rehearse. Try to adjust your framing and timing to accentuate the director's goals.

Be wary of shots where the actors don't change size — as if they are walking on a treadmill in front of a green screen. Sometimes it works, but most often it's a sign that everyone is just aiming for the end mark. Try to change the angle of the shot to emphasize spacewhen appropriate and to shoot straight forward or backward when a formal composition is required. Even a slight rake will take the shot into a more naturalistic realm.

Use your feet. Speed up, slow down. Get closer, move away. The Steadicam's big weapon is movement, and there's generally no good reason — beyond convention — to lock your movement to that of the actors'. (Our apologies to focus pullers here.) We're not advocating movement for movement's sake. When appropriate, let the actors change their size and position in the frame.

Use your arms, too. Try to micro-adjust your framing by moving the camera rather than panning or tilting. This keeps the background from shifting, which pulls the audience's attention away from the actors. Pan or tilt when you need to, but be careful.

The wider the lens, the more conscious you need to be of vertical lines keystoning at the edges of your frame. With really wide lenses, keep the Steadicam level fore and aft. You might want to add another bubble level to the sled to help you keep the post perfectly vertical.

Use marks where you can. The more precise everyone tries to be, the more specific, clear, and full the shot can be. All departments can be on the same page and contribute to the overall effect of the shot. Don't let all the regular production quality of filmmaking drop just because the Steadicam can move freely and correct for missed marks and timing. You do not want the shot to stick out like a sore thumb.

Suggestions for better walk and talks;

- Design a shot! Don't just walk along with the actors

- Enhance the drama: change the angle, size, distance, and speed.

- Make corrections with the arm instead of tilting or panning, thus minimizing angular change.

- Use marks, especially for key story points.