Steadicam® and vehicles

faster, farther, higher, lower

The very first Steadicam shot in a movie was a crane step-off in Bound for Glory. Garrett Brown was the operator,30 feet in the air on a Titan crane. The crane was lowered to the ground and Garrett stepped off to follow David Carradine across a field crowded with 900 extras.

Utilizing a vehicle with a Steadicam adds a new dimension to your storytelling opportunities. The operator's reach is extended,his stamina increased, concentration honed. The camera can literally fly through the air, speed down the road, hover next to a cyclist, or track with a cat stalking its prey.

All sorts of vehicles (dolly, crane, truck) can help you get these shots, but beware! Don't lose sight of the story. Don't move the camera for the sake of moving the camera, because it feels exciting to be strapped onto a vehicle, rig in your grasp, maneuvering around corners at a good clip.

Aesthetics of movement

Before Steadicam, the only viable option was to mount the camera directly to a vehicle or to shoot handheld. The camera was subject to all sorts of forces - centrifugal forces going around corners, hard accelerations and braking, bouncing over rough surfaces, etc. Often, if the road wasn't level, then the camera wasn't either. The Steadicam changed all that.

When shooting on a bus, train, boat, or other vehicle that is part of the story, the operator has some choice about whether to lock the Steadicam to the horizon, to the motions of the vehicle, or to some indeterminate world between the two.

In typical shots, the most realistic viewpoint is to lock the Steadicam to the horizon, as this matches our human viewpoint. However, this world view doesn't necessarily cut well with other, conventional shots in a vehicle sequence.

Conventional operators use hostess trays, hood mounts, and many other rigs that are essentially locked to the vehicle's motions. Audiences (DPs, operators, and directors, too!) have come to accept this non-realistic view as normal. Operators are often told to shake the camera during this sort of conventional shot to add realism!

Shooting from a camera car

Locking the Steadicam to the horizon tends to work best when the vehicle you are riding in is not pan of the story, but merely the camera support vehicle. Then our shots cut well with shots from grounded cameras — on a tripod, dolly, or crane — and even shots from helicopters and planes (properly stabilized, of course!).

Shooting vehicle to vehicle, you want to really watch your horizons and avoid bumps. Protect your sled from the wind as much as possible and add the heaviest Antlers that you can carry, or gyros. Let the arm absorb the bumps. New Steadicam operators often try to keep the sled in the same vertical spot relative to the vehicle, but you must let the arm float, up to a point.

Some operators like to harden the ride of the arm for this type of vehicle shot. A less isoelastic, more centerriding arm seeks the center float point more strongly and keeps the arm from rising or falling too far. However, a more center-riding arm needs more shock absorbing attention from the operator.

I find a strongly center-riding arm annoying; I like an arm that is as isoelastic as possible, so that it is less reac-tionary going over bumps, and I do less shock absorbing work. With an isoelastic arm, I only need to be con-scious of the biggest bumps.

With a G-type arm, you can instantly dial in any amount of isoelasticity or centering you like. Any arm of any design, however, can be made more center-riding (or less isoelastic), and you can make any arm resist going to the extremes of travel.

If you want a more centered ride,simply wrap the arm in a bungee cord for more lift, and dial down the lift from your arm's springs. The bungee's lift is going to be more centered (less isoelastic), so the whole arm will be more centered. You can also arrange a couple of bungees to be loose in the center of the arm's travel, and only start to pull on the arm when it gets closer to the end of travel, so you have a “normal” ride in the arm, but you protect the arm from going too far up or down.

Shooting inside a vehicle

When shooting inside a moving bus, train, or boat, etc., one tends to operate as if one was on terra firma, watching out, of course, for the odd lurch and the long and strong accelerations and decelerations. We tend to balance the sled normally (if anything with a slower drop time). It's easy to add motion to these shots, or, if you like, give the shots some extra tension by grabbing the post harder.

If we are in a larger vehicle where we can use the Steadicam, then it pays to use the Steadicam for the entire sequence, even for any static shots. Get a dolly or a tripod and hard mount to that for the static shots, and let the Steadicam lock to the horizon in all the shots.

Using a Steadicam to imply movement in the scene:

The Steadicam can be used to add movement to a scene where little or none exists.

The Bountty 0:26:26

In The Bounty, Toby Phillips rolled the camera to increase the violence of the storm sequence. Being out of sync slightly with the action increases the effect, but watch out for roosters giving it all away.

Take a look at the entire airplane sequence for The Twilight Zone (movie) — Garrett Brown yanked the camera all over to create turbulence, and he had the actors rise and fall with the camera as he lunged about the cabin.

Point of view shots

Character POVs from vehicles should generally be smooth and locked to the horizon (except for the most violent of vehicle motions), much like in a vehicle to vehicle shot. In cars, many of these POV shots are done handheld or off a bazooka in the back seat because there is no room for any other camera. Audiences, directors, and DPs arc accustomed to the old shake and bounce, and you've got to work harder to sell them the idea that it will look and feel better if shot with a Steadicam. We need to change the common language of the cinema here!

Different types of vehicle shots:

- Looking at another vehicle without revealing or calling attention to the vehicle the camera is riding

- Including the camera support vehicle, such as people talking inside a car

- Action inside a vehicle like a subway or a bus where the outside horizon is not ever revealed

- To get the camera moving up high or fast

- To get a good angle of a crowd or a landscape

A long time ago, Cinema Products made a special vehicle kit that rearranged the Model Ills parts into a Steadicam that fit into a car.

We were going to revolutionize the way audiences expenenced shots in cars! It didn't happen... (see page 294 for a picture of the Model II compact vehicle kit.)

Aerial vehicle: The Mighty Quinn

In 1989, Jimmy Muro wowed the world with an amazing tracking shot in The Mighty Quinn. As Denzel Washington jumps out of his jeep and runs down a hill past a burning house, the camera magically flies after him like a low helicopter, and then lands next to a crowd and follows Denzel running into the jungle behind the house.

The Mighty Quinn 1:20:07

Jimmy — operating two-handed for control over the image — stepped off a three-tier high scaffolding onto a modified contraption used by the grips to haul equipment and props for the movie up and down the hill. The platform was suspended from a heavy-duty cable, and pulled up the hill (or braked on the downward run) by a secondary line.

Once aboard, Jimmy shifted to operating onehanded — his arm hand now gripping the platform for dear life — and this was the signal to let him fly after Denzel as he ran down the hill. The secondary line controlled the descent and brought Jimmy to a semi-controlled stop, where he got off and continued the shot on foot around the back of the house. Because the speed of the move and the dismount were too fast, no safety rope or bandolier was slipped on and off.

A trusted assistant cued Jimmy to step off at the bottom of the run; things were happening so fast he could not even glance away from the monitor. Take one was the safety, and then, as Jimmy wrote for the December 1988 Steadicam Letter, “Once the security of a good take was in the can, we could live a little bit on the edge. Increase the speed. More flames. The third and final take was by far the most compelling and dramatic. An early step-off (near disaster) allowed another split second for Mr Washington to run toward the camera passing in a closer shot The spontaneity of this type of moment can't be up intentionally but it's what one remembers best about the whole shoot.”

This amazing shot inspired Garrett Brown to invent the Skyman™, a fancier and more versatile platform suspended from a cable — but one that does not allow the operator to get on and off during the shot.

Stepping off a crane:

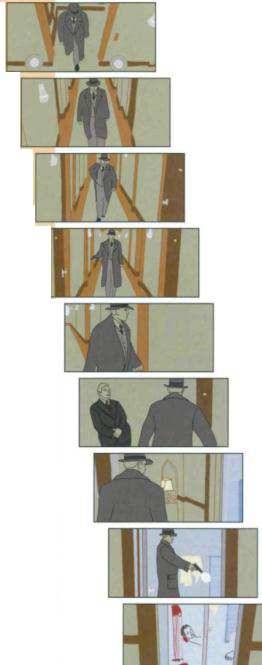

Road to Perdition

Personally, I absolutely love the spirit-like POV in the beginning of the shot, as Hanks's character ii about to commit his last murder and finish this war. We are watching from above now, he pieces have fallen into their places, it is out of our hands now. Although the camera eventually gets lower, we never clearly see his face, simply because there is no emotion to see there. He is a killing machine, efficient and cold,and the camera move accentuates that with its precision.

Road to Perdition 1:42:18

Scott Sakamoto was the Steadicam operator riding the crane, and you can see how tight his headroom is on Tom Hanks, as the ceiling pieces are rushed into position when the crane comes lower and lower. A pan is always the bestmoment to hide the step off from a crane, and Scott's step off is simply perfect.

A brilliant shot, in one of the best photographed films of all times.

—Michael Tsimperopoulos, on the Steadicam forum

On and off a golf cart:

Bonfire of the Vanities

The 5 minute opening shot of Bonfire of the Vanities is amazing in many ways, but here we want to point out how cleverly Brian DePalma and Larry McConkey worked with a golf can. The scene begins with Larry on foot, and looks like a typical walk and talk shot. Then the actors, the director, the Steadicam operator, and his assistant all climb on a golf cart, travel for hundreds of yards down a tunnel, get off the can and continue the scene — and it's all done without calling attention to itself.

Bonfire of the Vanities

Opening sequence

Look at the action (or the “misdirection” to use a magician's term) as Larry and the crew get on the cart, as the can starts and stops, and as Larry and the crew get off and continue the shot on foot. There are crosses, exaggerated business by the actors, tons of stuff to distract the audience as the tricky maneuvers take place.

A more mundane and typical method of shooting this pan of the scene would have been to use two golf carts and shoot from one to the other - so much duller and a lot less fun.