Tourism marketing

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

appreciate the scope of marketing as an essential component of tourism systems

list and describe the key characteristics of services marketing and explain how these are different from goods marketing

identify the strategies that can be adopted to address imbalances between tourism supply and tourism demand

explain when and why market failure occurs in tourism marketing

describe the role of destination tourism organisations in tourism marketing

outline the rationale for and the stages involved in strategic tourism marketing

define the basic components of the 8P marketing mix model

explain the pricing strategies that tourism businesses can use to set prices

identify the costs and benefits associated with the various forms of media that are used in tourism promotion.190

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Chapter 6 examined market segmentation, or the process whereby consumers are divided into relatively uniform groups with respect to their attitudes and behaviour. This is a critical component of tourism product management in that different market segments, distinguished by one or more geographical, sociodemographic, psychographic or behavioural criteria, are likely to have distinct impacts upon the tourism system. They also have different implications for tourism marketing, which is the subject of this chapter. Following a discussion of the nature and definition of marketing in the next section, the key characteristics of services marketing, and tourism marketing in particular, are examined. The need to maintain a balance between supply and demand is then discussed, while the phenomenon of market failure is addressed in the section that follows. This section also considers the approaches and strategies that can be used to overcome this problem. Strategic marketing, and in particular the components of a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis, forms the core of the ‘Strategic tourism marketing’ section. The final section presents an overview of the elements involved in the product-focused marketing mix.

THE NATURE OF MARKETING

THE NATURE OF MARKETING

Marketing is popularly perceived as involving little more than the promotional advertisements that are displayed through television and other media. However, these advertisements are only one form of promotion, and promotion is only one aspect of marketing. Advertising and promotion, and the people who work in these industries, are important, but marketing implicates everyone in the tourism and hospitality sector, including tourists, potential tourists and residents of destinations. Thus, marketing is explicitly or implicitly pervasive throughout the tourism system.

Definition of marketing

There are numerous definitions of marketing (see, for example, Kotler & Keller 2012; Morrison 2009). The following definition, which combines elements of the most commonly cited definitions, is used in this book:

Marketing involves the interaction and interrelationships among consumers and producers of goods and services, through which ideas, products, services and values are created and exchanged for the mutual benefit of both groups.

In place of the popular perception of marketing as a one-way attempt by producers (e.g. the tourism industry and destinations) to sell their products to the market, this definition emphasises the two-way interactions that occur between these producers and the actual as well as potential tourist market. Successful marketing, for example, depends on feedback (e.g. customer satisfaction, proclivity to purchase new products) flowing from the market to the producer. In addition, it recognises the importance of financial and other benefits to both parties, and includes interactions among the ‘internal customers’ within a company, organisation or destination.

SERVICES MARKETING

SERVICES MARKETING

Services marketing applies to service-sector activities such as tourism and is fundamentally different from the marketing of goods. This holds true even though the tourism sector interfaces with goods such as souvenirs and duty-free merchandise, 191and notwithstanding the fact that many important marketing principles are equally applicable to both goods and services. In general, the key marketing characteristics that distinguish services from goods are (a) intangibility, (b) inseparability, (c) variability and (d) perishability (Kotler, Bowen & Makens 2009).

Intangibility

In contrast to physical products, services have intangibility. This means that they can be experienced in only a very limited way prior to their purchase and consumption. Furthermore, customers usually have only a receipt, a souvenir or other memorabilia such as photographs as evidence that they actually had that experience. Customers purchase tourism and hospitality services for the first time with little more than knowledge of the price, some pictures of the destination and its facilities, endorsement by some well-known personality, friends or relatives or the sales intermediary (e.g. travel agent) and, in some instances, their own prior experiences. If they observe the delivery of those services to other customers, they may also develop some insight into the experience. In the service industry, the concept of compensation for an unsatisfactory purchase is also distinctive. As with goods, money can be refunded or compensating products made available free of charge, but the product itself cannot be returned once it has been consumed.

Because of the intangible nature of the service sector, word of mouth is especially important as a source of product information, as this involves direct or indirect access to those who have already experienced a particular destination or hotel. Accordingly, word of mouth has a high degree of influence among potential customers as an image formation agent (Morrison 2009). However, word of mouth can also be problematic. Circumstances regarding the product may have changed from the time of the informant’s experience, or the information may be third- or fourth-hand (e.g. the informant knows someone who knows someone who travelled to Bali and did not like it). In addition, the psychographic profile and tastes of the informant may be different from the person who is receiving the information (see chapter 6).

Thus, even with access to word-of-mouth information, the level of perceived risk in purchasing a service, especially for a first-time purchaser, is relatively high compared to goods (although this is not to say that goods purchasing is risk free). To reduce this risk perception, service providers offer tangible clues as to what the customer can expect from the product and the producer, thereby creating confidence in the service. For example, outdoor cafes often attract passers-by who see and smell the foods that are being served. Clues may also include articulate and uniformed personnel, a clean and professional office setting, glossy brochures that convey attractive images to the potential buyer, and websites that take advantage of virtual reality technologies.

Inseparability

Tourism services are also characterised by inseparability, meaning that production and consumption occur simultaneously and in the same place. This is demonstrated by a passenger’s flight experience (i.e. the flight is being ‘produced’ at the same time the passenger is ‘consuming’ it), or by a guest’s occupancy of a hotel room. Because the consumers and producers of these products are in frequent contact, the nature of these interactions has a major impact on customer satisfaction levels. Customer-oriented staff training and initial staff selection should thus ensure that frontline employees such as airline attendants and hotel receptionists display appropriate and positive emotional labour attributes such as empathy, assurance and responsiveness (Kim et al. 2012).192

Tourists also need to respect applicable protocol and regulations, since misbehaviour on their part can also negatively affect the product. For example, patrons who smoke in a smoke-free restaurant detract from the quality of the experience for non-smoking customers. Tourists who walk into a church wearing shorts and talking loudly or filming may offend local residents or other visitors. While it is assumed that frontline service staff should receive training to be made aware of appropriate standards of service behaviour, the same assumption is seldom if ever applied to tourists, even though these two examples clearly demonstrate the negative ramifications of inappropriate tourist behaviour. At the very least, it is incumbent on the service sector to make any relevant rules and regulations evident to tourists in a diplomatic but unambiguous way.

Variability

Tourism services have a high level of variability, meaning that each producer–consumer interaction is a unique experience that is influenced by a large number of often unpredictable factors. These include ‘human element’ factors such as the mood and expectations of each participant at the particular time during which the service encounter takes place. A tourist in a restaurant, for example, may be completely relaxed, expecting that their every whim will be satisfied, while the attending waiter may have high levels of stress from overwork and expect the customer to be ‘more reasonable’ in their demands. Such expectation incongruities are extremely common in the tourism sector, given the tourist’s perception of this experience as a ‘special’, out-of-the-ordinary (and expensive) occasion, and the waiter’s contrasting view that this is just a routine experience associated with the job. The next encounter, however, even if the same waiter is involved, could involve an entirely different set of circumstances with a more positive outcome.

The problem for managers is that these incongruities can lead to unpleasant and unsatisfying encounters, and a consequent reduction in customer satisfaction levels and deteriorating employee attitudes towards tourists. Often, just one such experience can have a disproportionate influence in souring a tourist’s view about a particular destination, offsetting a very large number of entirely satisfactory experiences during the same venture that, because they were expected, do not make the same impression. This is why a tourist returning to the same hotel may have a completely different experience during the second trip — the combination of moods, expectations, experiences and other factors among all participants is likely to be entirely different from the first trip.

This uncertainty element, combined with the simultaneous nature of production and consumption (which renders it more difficult to undo any mistakes), makes it extremely difficult to introduce quality control mechanisms in tourism similar in rigour to those that govern the production of tangible goods such as cars and clothing. For tourism destinations and products, it is again a matter of decreasing the likelihood of negative outcomes by ensuring that employees are exposed to high-quality training opportunities, and that the tourists themselves are sensitised to standards of appropriate behaviour and reasonable expectations that pertain to a particular destination.

Perishability

Tourism services cannot be produced and stored today for consumption in the future. For example, an airline flight that has 100 empty seats on a 400-seat aircraft cannot compensate for the shortfall by selling 500 seats on the next flight of that plane. The 100 seats are irrevocably lost, along with the revenue that they would normally 193generate. The smaller number of meals that needs to be served does not compensate for this lost revenue. Because some of this loss is attributable to airline passengers or hotel guests who do not take up their reservations, most businesses ‘overbook’ their services on the basis of the average number of seats that have not been claimed in the past. This characteristic of perishability also helps to explain why airlines and other businesses such as wotif.com offer last-minute sales or stand-by rates at drastically reduced prices. While they will not obtain as much profit from these clients, at least some revenue can be recouped at minimal extra cost. For a tourism manager, one of the greatest challenges in marketing is to compensate for perishability by effectively matching demand with supply. An optimal match contributes to higher profitability, and therefore the supply and demand balance is discussed more thoroughly in the following section.

MANAGING SUPPLY AND DEMAND

MANAGING SUPPLY AND DEMAND

Tourism managers will attempt to produce as close a match as possible between the supply and corresponding demand for a product. This is because, all other things being equal, resources that are not fully used will result in reduced profits. When considering the supply and demand balance, there are two main cost components that must be taken into account.

Fixed costs are entrenched costs that the operation has little flexibility to change over the short term. Examples include taxes, the interest that has to be paid on loans, and the heating costs that are incurred throughout a hotel during the winter season. In the latter case, these must be paid whether the rooms are occupied or not, as otherwise building and contents damage could result.

Variable costs are those costs that can be adjusted in the short term. For example, during the low season hotels can dismiss their casual nonunionised staff and cut back on their advertising, thereby adjusting to low occupancy rates by saving on salaries and promotion. It may also be possible to obtain cheaper and smaller supplies of food if the hotel is not already under an inflexible long-term contract with a specific supplier.

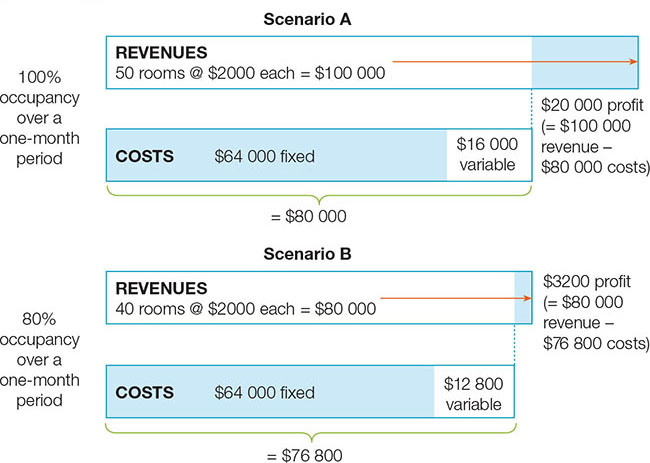

There is no set boundary between these two categories, and it is helpful to think of costs as falling along a fixed-to-variable spectrum that varies from one operation to another. Tourism businesses tend to have a relatively high proportion of costs concentrated in the fixed segment of the spectrum, implying that large amounts of money have to be budgeted whether a flight or hotel is fully booked or almost empty. As a result, even small shortfalls in occupancy can lead to significant declines in profit. Figure 7.1 demonstrates this problem by showing the contrasting profits that result from two different levels of occupancy in a hypothetical hotel with 50 rooms and monthly fixed costs of $64 000. In scenario A, full occupancy results in a $20 000 monthly profit when costs are subtracted from revenues. However, in scenario B, with just a 20 per cent decline in occupancy, the corresponding profit declines by 84 per cent to $3200. This is because the variable costs fall by 20 per cent (the same as the occupancy rate fall), but the $64 000 fixed costs cannot be moved at all. Being able to maintain a high occupancy rate is therefore absolutely critical for the hotel. Demand for tourism-related services such as accommodation, however, is usually very difficult to predict, given the complexity of the destination or product decision-making process (chapter 6), and the uncertainty factor associated with unexpected internal or external events (see Managing tourism: Getting them to visit after the bushfire). To help achieve a better understanding and thus a higher level of control over the demand portion of the supply/demand equation, daily, weekly, seasonal and long-term patterns in demand can be identified.

managing tourism

![]() GETTING THEM TO VISIT AFTER THE BUSHFIRE

GETTING THEM TO VISIT AFTER THE BUSHFIRE

Gippsland countryside devastated by bushfire

Natural and human-induced disasters affect all destinations sooner or later, yet marketers tend to take an ad hoc approach to promoting damaged destinations in the wake of such events. In 2009, the Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria collectively killed 200 people, displaced another 7500 and destroyed 3500 structures (Naidoo 2013). Following the initial period of mourning and attending to the needs of survivors, questions arose as to the content and timing of promotional material that would be most effective in attracting tourists back to affected areas to accelerate their recovery. Walters and Mair (2012) used an experimental design shortly after the bushfires to test the effectiveness of nine different taglines on potential visitors to Gippsland, one of the regions worst affected by the bushfires. Participants were 672 residents of other parts of Victoria, and they judged celebrity endorsement to be the most effective on the dimensions of ethos (i.e. trust and credibility), logos (i.e. facts and figures) and pathos (i.e. emotional response). Short-term discounts were least effective on ethos and pathos, while ‘open-for-business’ messages were least effective on logos. Also effective (although to a lesser extent) were ‘solidarity/empathy’ (‘Gippsland needs you…’), community readiness, challenging misperceptions (‘all roads are open’), curiosity enhancement (‘come see for yourself’), visitor testimonials, and festivals and events. While there was no significant relation between the type of tagline and the timeframe of a return visit, those who had visited Gippsland five times or 195more in the past were more likely to say that they would visit within six months of the bushfire, suggesting continuing loyalty. Tellingly, over 80 per cent agreed or strongly agreed that it was appropriate for affected destinations such as Gippsland to engage in post-disaster promotion sooner rather than later. A well-chosen celebrity — one, for example, who has a well-known association with the affected destination — appeared to be the most effective medium for capturing attention, providing credibility, and promoting awareness. In contrast, the open-for-business tagline was seen to lack credibility because of the dissonance between claims of a return to normality and relentless popular images of devastation released by the media.

Daily variations in demand

The level of demand for most tourism services changes throughout the day. For example, in a hotel reception area, the peak check-out time is in the morning between approximately 7am and 10 am, and in large hotels queues commonly form during that period if an efficient online check-out procedure has not been implemented. Similarly, late afternoon and early evening is a busy time, as guests arrive to check in. However, for the housekeeping department, the intervening period is usually the busiest time as rooms are cleaned and prepared before the next guests arrive. Different types of hotels also have different demand patterns. An airport hotel, for example, often faces unpredictable demand surges at any time of the day or night if flights are delayed or cancelled. In theme parks, a peak often occurs between midday and late afternoon, while country markets usually experience peak visitation in the early morning. Music festivals usually experience peak demand in the evening. When analysed from the perspective of daily demand, salaries are a fixed cost unless there is provision for sending staff home early without compensation.

Weekly variations in demand

Differential demand patterns on a weekly basis are illustrated in the hotel industry by the distinction between the ‘four-day’ and ‘three-day’ market. The four-day market is a largely business-oriented clientele that concentrates in the Monday to Thursday period. Hotels that focus on this market tend to experience a downturn on the weekend. Conversely, the three-day or short holiday market peaks on the weekend and during national or state holidays. Tourist shopping villages that draw much of their tourist traffic from nearby large cities, such as Tamborine Mountain and Maleny in Queensland, also tend to experience weekend peak use periods.

Seasonal variations in demand

Variations can also be identified over the one-year cycle, with a distinction being made between the high season, the low season and shoulder periods in many types of destinations and operations. 3S resort communities and facilities often experience 100 per cent occupancy rates during the high season, which is in the summer for high-latitude resorts and in the winter for tropical or subtropical pleasure periphery resorts. This may then be offset by closures during the low season due to very low occupancy rates, with subsequent negative impacts throughout the local community if appropriate adjustments have not been made (see chapter 8). In contrast, business-oriented city hotels and urban attractions often experience their seasonal downturn during the summer, when business activity is reduced.196

Long-term variations in demand

The most difficult patterns to identify are those that occur over a period of several years or even decades. Long-term business cycles, which have been identified by many economists (Ralf 2000), do not necessarily affect the usual daily, weekly and seasonal fluctuations, but can result in lower-than-normal visitation levels at all of these scales. Some tourism researchers have also theorised that destinations and other tourism-related facilities, irrespective of macro-fluctuations in the overall economy, experience a product lifecycle that is characterised by alternating periods of stable and accelerated demand. This very important concept is discussed more thoroughly in chapter 10.

Supply/demand matching strategies

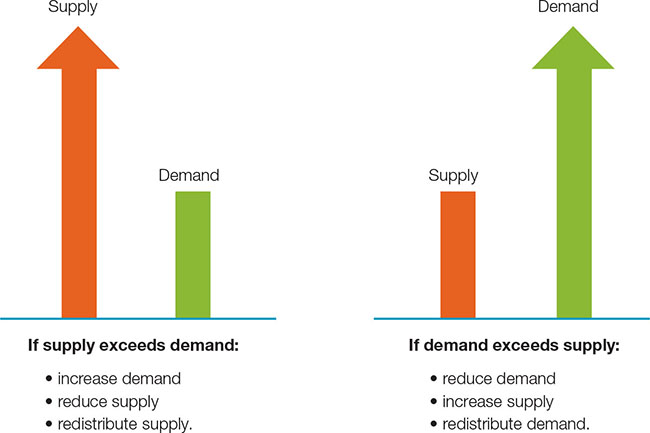

Most tourism managers operate in an environment that is largely capacity restrained — that is, supply is fixed and cannot be expanded rapidly. They therefore concentrate on optimising the volume of demand, although there is usually some scope for modifying supply as well. There are two broad circumstances in which a manager needs to take action — when supply exceeds demand and when demand exceeds supply — each of which is accompanied by its own set of strategies (see figure 7.2). The strategies that are adopted depend in large part on whether the imbalances are daily, weekly, seasonal or long term in nature.

FIGURE 7.2 Supply/demand imbalances and appropriate strategies

If supply exceeds demand: increase demand

The assumptions underlying this strategy are that either the total demand is below capacity or the demand is low only at certain times. Potentially, demand can be increased through a number of strategies.

Product modification or diversification is illustrated by attempts since the mid-1990s to incorporate the rainforests and farms of the Gold Coast’s exurban hinterland into that destination’s tourism product. To prevent supply from exceeding demand, during the 1990s many casinos in Las Vegas developed ‘family-friendly’ attractions and ambience 197to diversify their client base beyond hardcore gamblers, but then returned to an edgier approach with the slogan ‘What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas’ when growth in the family market slowed. Another strategy is the alteration or strengthening of distribution channels, as when a small bed and breakfast operation is linked with a large tour operator through its membership in a bed and breakfast consortium. Attempts since the early 2000s to cultivate the Chinese tourist flow to the Gold Coast, and to encourage domestic tourism within Australia, indicate the identification of new or alternative sources of demand, without necessarily modifying the existing product to any great extent. Another example is the increasingly popular practice of targeting people whose ancestors originally lived in the destination (see Breakthrough tourism: Going full circle with roots tourism). Pricing discounts, such as those provided by wotif.com (see preceding section), and redesigned promotional campaigns that focus more effectively on the existing product and market mix are other options.

breakthrough tourism

![]() GOING FULL CIRCLE WITH ROOTS TOURISM

GOING FULL CIRCLE WITH ROOTS TOURISM

The term ‘diaspora’ refers commonly to the movement of people away from their ethnic homeland, or the people themselves who have been affected in this way personally or through the migration of their ancestors. Roots tourism — the travel of diaspora members back to their ancestral lands as tourists — is a particularly attractive marketing option for a destination when diaspora numbers greatly exceed resident numbers, a strong sense of ethnic identity persists through the generations, and much of the diaspora resides in wealthy countries. All three criteria apply to Ireland. Globally, people with Irish ancestry are estimated to number 80 million (Simpson 2012), compared with Ireland’s current resident population of about five million. Most of these diaspora Irish live in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia or other wealthy countries, and many retain a very strong sense of ‘being Irish’. Although the diaspora has long been an important inbound tourist market in Ireland, Tourism Ireland recently made an ambitious year-long attempt to attract this market in its Gathering 2013 campaign (www.thegatheringireland.com). This involved clan gatherings, festivals, sporting events and concerts conducted throughout the year in different parts of the country. It was billed as a ‘spectacular celebration of what it means to be Irish’ (Simpson 2012). Not all Irish, however, were enthusiastic about the initiative, which some labelled as a cynical attempt by the financially struggling country to exploit cashed-up diaspora Irish who really don’t have that much of a connection with Ireland. Despite such dissent, many countries are assessing Ireland’s experience to see how their own large diaspora can be attracted. Notably, the neighbouring Scots launched their own Homecoming year in 2014 to attract some of the estimated 50 million overseas Scots. As more people move to other countries, and as interest grows in discovering one’s ancestral roots, roots tourism is likely to become a more prominent feature of destination marketing throughout the world.

Reduce supply

This strategy assumes that it is not possible or desirable to increase demand in any substantial way, and that it is desirable or essential to reduce costs. Supply can be reduced in hotels by closing individual rooms or wings, or by closing the entire hotel in the low season as an extreme measure to reduce fixed and variable costs. This strategy is commonly adopted in the Caribbean at the level of individual operations. Airlines react in a similar fashion by putting certain aircraft out of service, leasing these out to other companies, or cancelling flights.

Redistribute supply

Redistribution or restructuring of supply is necessary when the existing product is no longer suited to the demand it was originally intended to satisfy. In the case of a hotel, rooms can be modified to better reflect contemporary demand. This could involve the conversion of two rooms into an executive suite, or other rooms into ‘courtesy suites’ (used only during the day for showers and resting). New non-smoking rooms can also be provided. The conversion of hotel rooms into timeshare units is an illustration of a long-term adaptive strategy in the accommodation sector. Theme parks usually introduce new rides or renovate old rides periodically to sustain demand, while the conversion of scheduled flights to charter flights in the airline industry is another example of adaptive supply redistribution.

If demand exceeds supply: reduce demand

Where demand for a product exceeds its capacity, tourism product managers can raise the price of a seat or room, thereby reducing demand while obtaining additional revenue per unit. A similar demand reduction strategy is to increase entrance fees in national parks that are being negatively impacted by excessive visitation levels (see chapter 9). Another option often applied to protected areas and other natural or cultural sites but seldom to countries or municipalities is a formal quota on the number of visitors allowed per day, month, season or year. Peak season whitewater rafting on the Colorado River in Grand Canyon National Park (United States), an extremely high-demand experience, is regulated by a dual waiting list/lottery system that can result in a 20-year period between registration and participation. Some destination managers may also take the controversial move of proactively discouraging visits from some or all tourists on a temporary or permanent basis. This demarketing can be ‘general’ when it attempts to restrict visits by all potential tourists, or ‘selective’ when it focuses on a particular (usually undesirable) segment such as football hooligans or sex tourists (Armstrong & Kern 2011).

Increase supply

As an alternative to induced demand reduction, managers can accommodate higher demand levels by expanding current capacity. Many 3S resort communities respond effectively to short-term demand fluctuations by making their patrolled beaches available on the basis of daily or weekly patterns of demand. A hotel can build an additional wing, acquire new facilities or utilise external facilities on a temporary basis. To increase bed capacity in a single room, cots and convertible sofas are often provided. Primitive hut-type accommodations, such as the bures provided by some Fijian hotels, have the great advantage of being highly attractive to 3S tourists. However, at the same time, they can be erected and disassembled rapidly depending on seasonal fluctuations.

A similar principle applies to the tent-like structures available commercially at various eco-resorts in Australia and elsewhere. At Karijini Eco Retreat in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, deluxe ‘eco tents’ can be easily erected and dismantled 199with minimal environmental disturbance (see figure 7.3), but include a private ensuite bathroom, front and rear decks and other high end features (see figure 7.4). Solar power, natural ventilation and recycled timber flooring add to their strong environmental credentials. As with bures, they are an effective means of meeting the problem of high fixed costs associated with ‘permanent’ facilities.

FIGURE 7.3 Deluxe eco tent at the Karijini Eco Retreat, Western Australia

Source: Christian Fletcher (Photographer) & Karijini Eco Retreat

FIGURE 7.4 Typical interior configuration of a deluxe eco tent

Source: Christian Fletcher (Photographer) & Karijini Eco Retreat

200

200

Redistribute demand

This strategy works by transferring demand from times of excess use to times of low demand. The differential seasonal price structure in many Caribbean resorts, for example, is an attempt to redistribute demand from the high-demand winter period to the low-demand summer season. At the weekly scale, many attractions attempt to divert traffic from the busy weekend period to the rest of the week by offering weekday discounts on entrance fees and other prices.

MARKET FAILURE

MARKET FAILURE

Tourism is an industry where market failure occurs frequently. Mainstream economic theory suggests that market demand and product supply will attain equilibrium in the long term. Companies that identify a need for promotion to fill their hotel rooms or aircraft seats, therefore, will spend the necessary funds on that promotion. In return, they will benefit financially from their investment when the anticipated increase in demand materialises. In destination marketing, however, the case is not so straightforward. It is widely recognised that tourists usually decide first on a particular destination, and then select specific tourism products (e.g. accommodation) within that destination. However, specific tourism operators are rarely willing to invest money directly in destination promotion, since this type of investment will provide benefits to their competitors as well as to themselves. Hence, the situation arises where financial investment is required for destination promotion to achieve demand/supply equilibrium but operators are unwilling to contribute since the returns do not accrue directly to the individual companies. The market therefore does not function as it should in taking action to attain supply and demand equilibrium.

Destination tourism organisations

Destination promotion, as a result, is normally the responsibility of destination tourism organisations (DTOs) established as government or quasi-governmental agencies at the national, regional, state or municipal level. This is a role that serves to reinforce the importance of destination governments within the overall tourism system. Historically, such bodies have been funded from general tax revenues, and therefore individual tourism operators receive direct benefits from destination promotion that the wider community (including the tourism businesses) has funded. However, this public funding is usually justified by the tax revenues, jobs and other economic benefits that trickle down from prosperous tourism businesses to the broader community (see chapter 8).

Market failure has implications not only for destination promotion and marketing but also applies to the provision of infrastructure (i.e. the roads and airports that benefit businesses but are also funded through general tax revenues), specific tourism facilities (e.g. convention centres) and tourism research. However, in the present context of tourism marketing it is the area of promotion and those related activities that are particularly relevant. The following subsections will therefore discuss some of the marketing functions that are usually performed by DTOs such as Tourism Australia (www.tourism.australia.com), Tourism and Events Queensland (www.tq.com.au) and Gold Coast Tourism (www.visitgoldcoast.com), depending on mandate and level of available funding.201

Marketing functions of destination tourism organisations

Historically, the principal marketing role of DTOs was promotional. However, despite widespread funding reductions, this is changing as the contemporary international tourism industry becomes more competitive and complex, and tourists become increasingly sophisticated in their destination choice behaviour. Progressive elements within the tourism industry, accordingly, recognise the importance of collaboration between the public and private sector in implementing effective marketing strategies.

The following sections describe the activities ideally carried out by a well-funded and collaborative destination tourism organisation.

Promotion

Advertising directed at key market segments is a core activity and is often focused on fostering destination branding, or efforts to build a positive destination image that represents that destination to certain desired markets (Tasci 2011). The extremely successful ‘100% Pure New Zealand’ campaign, for example, employs the common logo and slogan but different activities and images in the key inbound markets of Australia, Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and Singapore. For example, the ‘100% Pure New Zealand’ website for Australia emphasises the capital city of Wellington, the Te Papa national museum, native animals, wineries, boat cruises on the Marlborough Sounds and the Queen Charlotte Track. It links to the Qantas website to facilitate the online flight bookings. Six entirely different experiences are recommended on the Singapore website — that is, Milford Sound boat cruises, the beaches of the Coromandel Peninsula, Rotorua’s geothermal features, glaciers, Waitomo’s glow worm caves, and jet boating. More recently, this campaign has been applied in a highly successful way to New Zealand’s association with the Lord of the Rings and the Hobbit movie trilogies (see the case study at the end of this chapter). To expedite these campaigns, larger DTOs often maintain offices in the major cities of key market countries. Related activities include participation in domestic and international tourism trade shows, the organisation of familiarisation tours for media and industry mediators, handling media inquiries and coordinating press releases. DTOs also produce and distribute or coordinate the production and distribution of promotional material and work to promote a favourable destination image in key origin regions. Some organisations engage in joint promotion with other jurisdictions.

Research

Research, or the informed acquisition of strategic knowledge (see chapter 12), is an increasingly important activity pursued by destination tourism organisations. This can focus on visitation trends and forecasting, identification of key market segments and their expenditure and activity patterns, perceptions of visitor satisfaction and effectiveness of prior or current promotional campaigns. If resources are available, these bodies may also try to identify the key threats and opportunities presented by external environments.

Direct support for the tourism industry

Although the tourism industry and its constituent subsectors maintain their own representative bodies, DTOs often provide support to new and existing tourism businesses, advise on their product development and otherwise assist in educating and encouraging the industry (see Technology and tourism: E-helping small businesses with the tourism e-kit). They may also function as a lobby group to represent the interests of their constituents in relevant political or industry arenas.

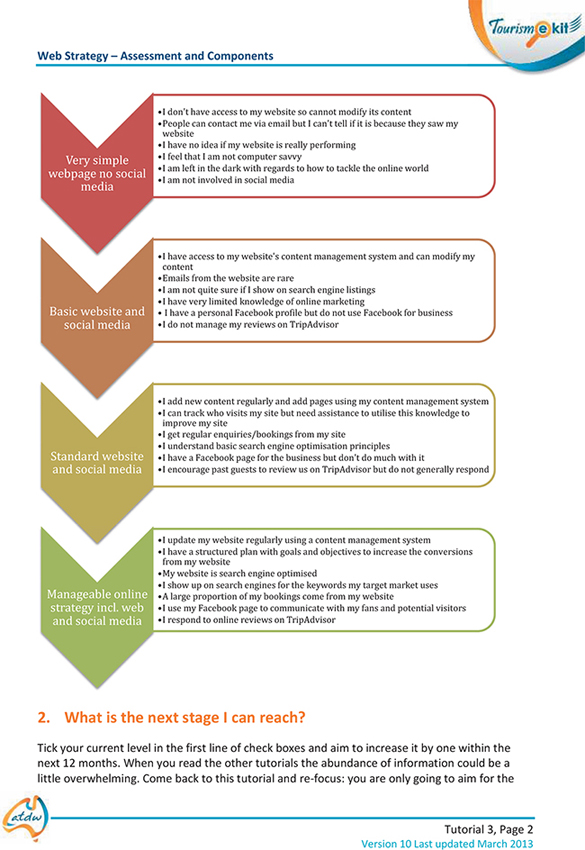

![]() E-HELPING SMALL BUSINESSES WITH THE TOURISM E-KIT

E-HELPING SMALL BUSINESSES WITH THE TOURISM E-KIT

The Australian Tourism Data Warehouse (ATDW) was established in 2001 as a joint initiative of Tourism Australia and all Australian State and Territory Government tourism organisations to fill an identified need to market a comprehensive range of Australian tourism products. As a service to industry the ATDW developed the Tourism e-kit, a free online tool which helps business operators maximise their online marketing capabilities (ATDW 2012a). The e-kit is a self-paced adult learning tool which can be consumed online, in print, in video and through formal and informal 204workshops held by qualified trainers. The product is divided into 64 tutorials across 9 subject areas, available as PDF files or as YouTube videos downloadable from the Tourism e-kit microsite (www.tourismekit.com.au).

Initial content is concerned with introductory topics such as an evaluation of the viewer’s current website, formulating an overall web-based marketing strategy, considerations of cost and timing, finding good professional assistance, and best practice for effective use of email. Subsequent tutorials focus on developing an effective website and include topics such as registering a domain name, Web 2.0, visual design, content management and catering to smart phone users. Other tutorials focus on search engine optimisation, e-marketing, analysis and statistics of site use, online distribution options and online bookings (which has proven to be the most popular tutorial to date). One of the largest segments covers social media topics such as online tourism communities, Facebook, Twitter, online reputation management, TripAdvisor, YouTube, Flickr and blogging. The final five tutorials all deal with working digitally to access the China market, emphasising, for example, how Chinese search engines and social media usage differ from their Western counterparts. Tutorials average about 20 minutes each, with a total time of 15 hours, and no prior knowledge of or experience with online technology is required. These characteristics make the e-kit especially appropriate for small businesses that lack specialised expertise, available time or the financial resources to access this type of information elsewhere.

With the fast-changing digital environment, it is critical that the e-kit maintains its relevance and accuracy. This is achieved through 6-monthly updates by ATDW and expert contributors. Since its inception, the e-kit has grown and new topics have been added, based on regular industry consultation and feedback. As of 2013 the e-kit has been downloaded over 300 000 times, indicating effective exposure to the intended market. The e-kit was awarded first place at the 2011 and 2012 Queensland Tourism Awards in the Education and Training category (ATDW 2012b) and was also awarded Silver in the National Tourism Awards in 2012.

Information for tourists

This function is distinct from promotion in its emphasis on providing basic information to tourists who are already in the destination through tourist information centres at key destination sites and gateways. Related functions are usually informed by and directed towards the overriding strategic objectives of the DTO. In the case of Tourism Australia, a national DTO, the latter include:

influencing tourists to travel to Australia to see sites as well as to attend events

influencing visitors to travel as widely as possible throughout Australia

influencing Australians to travel within Australia, including for events

fostering sustainable tourism within Australia, and

helping to realise economic benefits for Australia from tourism (Tourism Australia 2013a).

Such broad objectives are usually shared and/or developed in conjunction with the destination tourism authority (DTA), which is the government agency (usually a department or office within a department, and sometimes the same agency as the DTO) that is responsible for broad tourism policy and planning.

National DTOs are normally mandated to promote the country as a whole, which can generate conflict with states or provinces that perceive an imbalance in coverage with respect to their own jurisdiction. For example, South Australia and Western 205Australia might complain that Tourism Australia places too much emphasis on iconic attractions such as the Sydney Opera House, the Great Barrier Reef and Uluru, thereby reinforcing the tendency of inbound tourism to concentrate at these locations. While DTOs are sympathetic to such concerns and do try to integrate less frequented locations into their publicity and strategic planning (as per the mandate of Tourism Australia), the presentation of icons serves to reinforce distinctive and positive images that are pivotal for inducing potential tourists to favour Australia over its competitors. One way that DTOs can compromise between the more popular and less-known internal destinations is to portray generic lifestyles and landscapes that do not evoke specific places. Frequently, these images are varied to target particular markets identified by segmentation research. As of 2013, Tourism Australia focused on seven core ‘experiences’ that each apply to most states or territories. These were ‘Aboriginal Australia’, ‘Nature in Australia’, ‘Aussie Coastal Lifestyle’, ‘Outback Australia’, ‘Food and Wine’, ‘Australian Major Cities’, and ‘Australian Journeys’ (Tourism Australia 2013b).

STRATEGIC TOURISM MARKETING

STRATEGIC TOURISM MARKETING

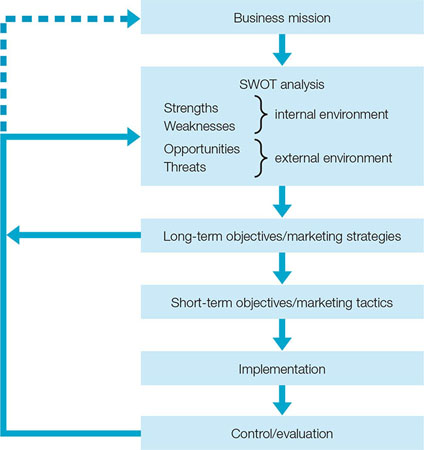

Whether undertaken nationwide by a DTO and/or a DTA, or by a business just for itself, effective tourism marketing must take into account the basic mission statement of the organisation, and both the internal and external environment of the destination or company (see figure 7.5). The mission statement is usually some very basic directive that influences any further statement of objectives or goals. For example, a DTO’s mission statement usually espouses a viable, sustainable and expanding tourism industry as a means of improving the national economy, and hence quality of life for citizens. A business, in contrast, may have a mission of offering the highest quality products within a particular sector.

SWOT analysis and objectives

SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) is a popular and proven method for facilitating strategic marketing and management. The strengths and weaknesses component refers to the internal environment of the destination or business, while opportunities and threats are factors associated with the external environment. Internal and external factors, however, often overlap.

The external environment includes not only elements of the general environment (i.e. the external technological, political, social, cultural and physical environments of tourism systems, as discussed in chapters 2, 3 and 4), but also an analysis of competing destinations or businesses. Key questions when examining the external environment include the following:

Who are our competitors? (For example, New Zealand is a competitor of Australia, but Queensland competes with New South Wales within Australia.)

What strategies are being employed by our competitors?

What are their strengths and weaknesses?

Who are their customers, and why do they purchase their products?

What are their resources?

What kind of relationships do we maintain with these competitors?

What nontourism external environments are affecting or are going to affect us? How much can we influence these environments?

206FIGURE 7.5 Strategic tourism marketing

Questions that are pertinent to the internal environment of the destination or company include the following:

What is the current level of our visitation or patronage, and how does this compare with past trends?

What products do we have available, currently and potentially?

Who are our customers, and how are they segmented?

What are the activities and behaviour of our customers?

How satisfied are our customers with our available products?

What are the reasons for these satisfaction levels?

How effective are our current destination branding efforts?

What are our available financial and human resources?

Objectives

A SWOT analysis assists in the identification of long-term objectives for the company or destination. Such horizons may extend to the next ten or 15 years, but are usually not less than five years. Given the complex and unpredictable nature of the factors that will influence tourism over that timeframe, it is not sensible to stipulate specific long-term objectives. Rather, the objectives should reflect characteristics that are likely to remain desirable in ten or 15 years whatever else transpires. Relevant long-term objectives for a destination might include:

increase the average length of stay

increase average visitor expenditures per day

increase the proportion of inputs (e.g. food, labour) that are obtained from within the destination, in order to assist other local businesses207

achieve a more dispersed distribution of the tourism sector

diversify the market base to reduce dependence on the primary markets

ensure that tourism development occurs in an environmentally and socioculturally sustainable way.

Given a different set of priorities, the long-term objectives for a company are likely to be very different to those identified by destination managers — for example, to be the most highly capitalised company and to capture the largest share of consumer dollar in the sector.

Based on the broad and deliberately vague objectives and goals that are formulated for this extended timeframe, more specific short-term goals and marketing tactics should be established that have a horizon of six months to three years, depending on feasibility. Short-term goals that parallel the long-term objectives noted above might include:

increase the average length of stay from 2 days to 3 days within the next two years

increase average expenditures from $100 to $150 per day over the next two years

initiate legislation within the next year that requires hotels to obtain at least one-half of their food inputs from local suppliers

increase the promotional budget for regional tourism attractions by 10 per cent in the next financial year

open three new tourist offices in large but nontraditional markets over the next three years

limit the increase in annual arrivals to 5 per cent a year over the next two years.

Control/evaluation

These precise figures and target dates inform the implementation process, and allow for a performance evaluation — have they been achieved or not? The control/evaluation process provides feedback for further SWOT analyses, which reassess the internal and external environmental factors that have helped or hindered the attainment of the objectives. This in turn may lead to a reassessment of the long-term and short-term objectives, as well as associated marketing strategies and tactics. It is also useful to periodically evaluate the SWOT procedures themselves to ensure that the best methodologies are used to assess the best quality information.

Strategic marketing recognises that a tourist destination or company does not exist in a vacuum. Such entities are just one component in complex tourism systems that are in turn affected by myriad factors generated in environments that are external to those systems. It also recognises that the managers of successful destinations, however success is defined, must have a vision for the future, an awareness of the strategies that are required to achieve success and the will and means to carry out those strategies. Only with long-term thinking will destinations and businesses minimise negative impacts and attain a sustainable tourism sector (as discussed in the following four chapters).

MARKETING MIX

MARKETING MIX

The critical components that determine the demand for a business or destination product are collectively known as the marketing mix. Several different marketing mix structures have been proposed, a popular one being the 8P model (Morrison 2009), which includes the following:

All these components need to come together in a mutually reinforcing way to achieve maximum effectiveness. In many respects the marketing mix factors discussed below overlap with the pull factors that were considered in chapter 4 and — if successful — have the cumulative effect of ‘pulling’ tourists to the destination. One major difference is that the 8P model reconfigures those factors in a way that facilitates marketing and promotional efforts. That is, they are conceptualised as factors that can be marketed and managed to the greatest possible extent. In addition, the marketing mix is applicable to individual companies and products as well as destinations.

Place

As indicated in chapter 4, place is essential because tourists must travel to the destination in order to directly consume the tourist product. Relative location (proximity to actual and potential markets and competitors) is a critical element of place, as is coverage (the other places that are identified or not identified as target markets for marketing and promotional efforts). Australia, for example, maintains a highly visible presence in East Asia, New Zealand, western Europe and North America, but places a low priority on emerging markets in Africa, eastern Europe and Latin America. Accessibility represents the extent to which the markets and destinations are connected, and this too must be taken into account in marketing strategies. Essentially, these three elements encompass the three geographical elements of tourism systems, as discussed in chapter 2 — destination regions, origin regions and transit regions.

An increasingly important concept in the marketing mix is sense of place (see chapter 5), which brands the destination as a unique product offered nowhere else, thereby enhancing its competitive advantage by positioning it at the ‘unique’ pole of the scarcity continuum. This strategy, moreover, has important implications for a destination’s environmental and sociocultural sustainability, because it counteracts the tendency towards uniformity and community alienation that characterises many destinations as they become more developed (see chapters 9 to 11) (Moskwa 2012). A desirable outcome from sense of place is place attachment, which is associated with high loyalty.

Product

The product component encompasses the range of available goods and services, their quality and warranty and aftersales service. ‘Range’ is a measure of diversification, and can be illustrated by a tour operator that offers a broad array of opportunities, as opposed to a niche operator. Similarly, a destination may provide a large number of diverse attractions, or just one specific attraction. The concepts of quality and warranty must be approached differently when comparing a destination with a specific operator. In the case of a specific operator, the manager of the business exercises considerable control in ensuring that the customer receives certain specific services in a satisfactory way, and that some kind of restitution is available if the customer is unsatisfied. In a destination, however, there is relatively little that the manager can do about litter-strewn streets, unfriendly residents and the persistence of rainy weather during a tourist’s entire visit. This is because much of the ‘product’ consists of generic, public resources over which the tourism manager has minimal control and no scope or direct obligation to provide any warranties for unsatisfactory quality. Similarly, the notion of aftersales service is difficult to apply to tourism services or destinations, and is mainly restricted to determining tourists’ post-trip attitudes about their tourism experience.209

People

People enter the marketing mix equation in at least three ways:

service personnel

the tourists themselves

local residents.

The service personnel issue was considered earlier under the topics of inseparability and variability, which demonstrated the critical role of highly trained employees and emotional labour at the consumer/product interface. The importance of fostering tourist sensitivity and awareness was also stressed, since inappropriate tourist behaviour can reduce the quality of the product for all participants. For many destinations, the local residents also fall into the category of product, since tourists may be attracted by the culture and hospitality of the resident population. Again, tourism managers can attempt to control public behaviour towards tourists through education programs, but there is very little that can be done in the way of quality control if some local residents maintain a hostile attitude, unless this is expressed in unlawful behaviour.

It has been argued that the treatment of residents as a mere element of ‘product’ that can be manipulated for the benefit of the tourism industry and tourists is an approach that breeds hostility and resentment within the local community. As a result, a community-based approach to tourism management and planning, which gives first priority to the needs and wants of residents and acknowledges their lead role as decision makers, has become more popular — however, it is also more difficult to implement than conventional models (Iorio & Wall 2012). High-level input from the community is, additionally, more conducive to the development and presentation of a product that effectively conveys the destination’s sense of place.

Increasingly sophisticated computer software and data analysis techniques have greatly facilitated the incorporation of the ‘people’ component into the marketing mix by allowing a comprehensive array of behavioural and demographic tourist characteristics to be compiled and analysed. Such developments make possible the identification of the niche markets and markets of one described in the previous chapter, and also allow managers to identify and target market the type of consumer who is most likely to patronise their products. Loyalty schemes such as airline frequent flyer programs, promoted as a concession to loyal customers, greatly benefit their sponsors through the customer databases that they generate (Vogt 2011).

Price

Affordability is a critical pull factor in drawing tourists to particular destinations. Airlines, attractions and hotels commonly reduce their prices until a desirable level of occupancy is achieved (i.e. a strategy of increasing the demand), given the profit implications of empty seats or rooms for products that have high fixed costs (see figure 7.1). However, the relationship between reduced price and increased patronage is not entirely straightforward, as many consumers perceive price as an indicator of quality — if the price is too low, this might indicate a poor-quality product. For this reason, reduced price may dissuade wealthier travellers who can afford higher prices, and may convey a lasting image of poor quality. Permanent or temporary discounts, nevertheless, are often used to target specific groups who are sensitive to high prices, including older adults, families and students.210

Given the importance of price in a high fixed cost environment, it is important for tourism managers to be aware of the pricing techniques that can be employed by businesses. The emphasis here is on companies, since the cost of a destination is mostly based on the cumulative pricing decisions of the businesses and operations, public and private, that function within that destination. Destination managers might possibly influence those prices through tax concessions, grants, regulations and other means, but cannot by themselves determine the pricing structure. The pricing techniques can be separated into four main and largely self-explanatory categories as follows.

Profit-oriented pricing

Pricing techniques that are oriented towards profit include typical approaches such as the maximisation of profits and the attainment of satisfactory profits (however these might be defined) and target return on investment. Such strategies do not place the priority on what the competition is doing.

Sales-oriented pricing

There are many varieties of pricing techniques that focus on consumer sales. These include basing the strategy on the prices that the market, or some target segment thereof, is willing to pay for a product, maximising the volume of sales, increasing market share through (for example) aggressive promotion and reduced prices, gaining market penetration through low initial entry prices, and maintaining high prices as a signal of outstanding quality (prestige pricing).

Competition-oriented pricing

The emphasis here is on competitor behaviour as the major criterion for setting prices. This reactive approach can involve the matching of a competitor’s prices, or the maintenance of price differentials at a level above or below the competitor’s prices, depending on the type of market that is being targeted.

Cost-oriented pricing

These strategies base pricing structures on the actual cost of providing the goods or services. First, costs are established, and then an appropriate profit margin is added. This margin can be either a fixed sum (e.g. $50 per ticket) or a relative amount (e.g. 10 per cent profit per ticket). It is a common practice in cost-oriented pricing to calculate break-even points — that is, combinations of price and occupancy where revenues and costs are equal (e.g. $100 per room at 84 per cent occupancy, or $120 per room at 70 per cent occupancy). Any incremental increase in occupancy above the break-even point represents a profit margin.

Packaging

Packaging refers to the deliberate grouping of two or more elements of the tourism experience into a single product. This is best illustrated in the private sector by the provision of set-price package tours that integrate transportation, accommodation, visits to attractions and other complementary tourism components (see chapter 5). For destinations, the packaging element can be more ambiguous and informal, involving attempts by NTOs or subnational tourism organisations to market the destination as an 211integrated ‘package’ of attractions, activities, relevant services and other tourism-related opportunities. For Australia’s Gold Coast, the ‘Green Behind the Gold’ campaign in the 1990s was an explicit attempt to package the rainforest experience with the beach experience.

According to Morrison (2009), packaging is popular because it provides greater convenience and economy for customers, allows them to budget more easily, and eliminates the time required to assemble the constituent items themselves. From an operator perspective, packages can stimulate demand in off-season periods (e.g. ‘summer special packages’), attract new customers, encourage the establishment of partnerships with operators offering the complementary services, and make business planning easier (in part because packages are often paid for well in advance of the experience). Interestingly, the package tour became a symbol of standardised mass tourism in the modern tourism era, although it is now increasingly approached as a ‘boutique’ service in which unique packages are assembled for individuals according to their specific wants and needs.

Programming

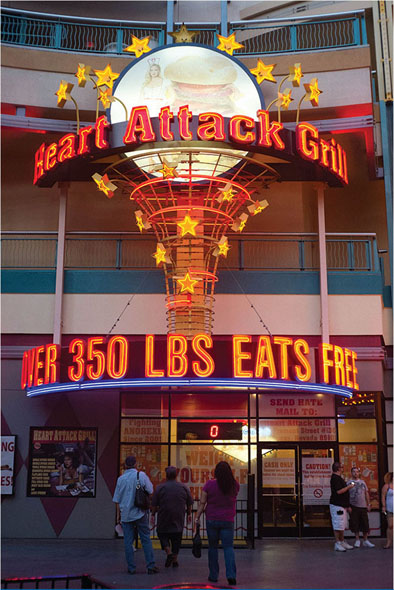

Programming is closely related to packaging in that it involves the addition of special events, activities or programs to a product to make it more diverse and appealing (Morrison 2009). Examples include the inclusion of scuba diving lessons or academic lectures on a cruise, ‘chance’ encounters with historical impersonators at a heritage theme park, broadcasting live rugby matches at a sports bar and the periodic announcement of prizewinners at a convention. For the theme park or sports bar (or, potentially, the destination), such program add-ons allow the operator to alter their product package frequently and inexpensively without having to undertake risky and costly actions such as introducing new rides or menus. Moreover, the programs could be altered to draw specific market segments (e.g. broadcasting women’s hockey to attract young adult females). An unusual application of programming is found at Heart Attack Grill, a chain of restaurants in the United States which unapologetically offers extremely high calorie and unhealthy food (e.g. the Triple Bypass Burger) (see figure 7.6). Customers are required to wear hospital gowns and have their temperature and blood pressure periodically taken by waitresses dressed as nurses. Customers who manage to eat the Triple or Quadruple Bypass Burger are escorted out to their car in a wheelchair by their ‘personal nurse’.

FIGURE 7.6 The Heart Attack Grill

Promotion

As indicated earlier, many people see promotion as being synonymous with marketing. Promotion attempts to increase demand by conveying a positive image of the product to potential customers through appeals to the perceived demands, needs, tastes, values and attitudes of the market or a particular target market segment.

presentation

personal selling

sales promotion

publicity

merchandising

advertising.

Presentation can include the provision of uniformed and well-groomed staff and an attractive physical environment, which give potential customers a favourable impression of the company. Personal selling entails a direct approach to a particular client, usually a large corporation whose potential patronage justifies the added costs of this individual approach. Sales promotions are short-term strategies that promote a product through temporary discounts (e.g. special discount of 80 per cent off a product for one day only in order to increase exposure to consumers).

Publicity

Publicity can occur through press releases and is one of the least expensive means of promotion, and one that can be readily used by destination managers. Even better is coverage by way of a National Geographic magazine article or television special accessed by millions of consumers. However, there is a higher risk in such unsolicited media coverage that the publicity, and resulting product image, will be negative. One example is the negative national media coverage that attends the annual Schoolies Week event on the Gold Coast, which forces the destination managers to engage in damage control by releasing its own counterbalancing publicity.

Merchandising

Merchandising can be used very effectively as a promotional tool when it involves the sale of products, at on-site gift shops or online, that are readily associated with a particular company or destination (Schauder 2012). This might involve items of clothing on which a resort or tour operator’s logo is prominently displayed, or custom furnishings used in a hotel room. There are several advantages associated with well-formulated merchandising strategies.

First, unlike other forms of promotion, merchandising also generates direct income, and all the more so since logo products often sell at a premium.

Second, since such products are usually purchased as souvenirs, they tend to be prominently displayed as status symbols back in the origin region, thereby maximising exposure to potential customers.

Third, it is commonly the more frequently worn items of clothing, such as baseball caps and T-shirts, that are merchandised, and therefore the purchasers of these products are likely to spend more time acting as walking billboards for the company or destination.

Hard Rock Café illustrates the effective application of merchandising to the tourism sector. More of the company’s revenue is generated from the sale of Hard Rock Café-branded merchandise than from food and beverages. The range of available items has expanded from simple but enormously popular T-shirts to lapel pins, teddy bears and beer glasses. Because of their desirability as collectables, many consumers purchase two items — one for display as a status symbol (e.g. a T-shirt or key chain) and one preserved in mint condition for its future resale value. More ingeniously, names of individual locations (e.g. Surfers Paradise, Las Vegas) are included on certain items of merchandise, making each one a discrete collectable, prompting dedicated collectors to obtain specimens from every Hard Rock Café worldwide.213

Advertising

Advertising is the most common form of promotion, and constitutes a major topic of investigation and management in its own right. An important distinction in advertising can be made between a ‘shotgun approach’ and a ‘rifle approach’. In shotgun marketing, an advertisement is placed in a mainstream media source that is accessed by a broad cross-section of the tourist market. As with a shotgun, much of the delivery will miss the target audience altogether (unless the market is an inclusive one, as in the case of a Disney theme park), but the high level of saturation will ensure that the target audience will also be reached. For example, an advertisement for a backpacker hotel in Time magazine will be ignored by most readers, but will almost certainly reach a large number of backpackers who read this magazine. Shotgun marketing also attracts new recruits to the product, that is, non-backpackers whose interest is aroused by a compelling advertisement. The high costs associated with the mainstream media, however, are a major drawback to this approach, as is the steady loss of customers to more specialised online media.

In contrast, rifle marketing occurs when the advertisement is directed specifically to the target market, like a single bullet fired from a rifle. This would occur if the aforementioned hotel advertisement were placed in a backpackers’ magazine or posted on the online forum of a specialty organisation or online community. Its major disadvantages are the lack of product exposure to the broader tourist market and competition with the advertisers of similar products. Beyond the shotgun/rifle dichotomy, a major decision in advertising and public relations dissemination is the selection of a media type that will best convey the desired message to the target market. Major media outlets will now be discussed, (with the exception of travel guides, which were discussed in chapter 5 as a form of merchandise).

Internet and social media

The internet and social media are rapidly overtaking traditional media outlets such as television and hard copy newspapers in magnitude, although this is difficult to quantify because of their diffuse nature. The creative use of the internet as a promotional tool and distribution channel is illustrated by the rapid development of webcasting technologies, which deliver interactive multimedia (video and audio) in real time. Configured effectively, webcasting can help to overcome the intangibility dilemma discussed earlier. Other internet platforms that are being increasingly implicated in formal and informal marketing of tourism products and destinations include Facebook, Twitter, wikis and microblogs. Given the rapid development of such technological innovations, it is not surprising that the internet continues to grow in popularity as a means of accessing information about potential destinations and other tourism-related goods and services.

An extremely important characteristic of the internet is its democratising effects. That is, almost anyone can develop and update a website due to their low cost and technical simplicity, which means that even the smallest operator or destination can obtain the same potential exposure as any large corporation. Similarly, internet features such as blogs and chat rooms allow almost anyone to expose their opinions to a potentially large audience. In both senses, the internet is therefore instrumental in levelling the promotional ‘playing field’ through electronic word-of-mouth communication, or eWOM (Litvin, Goldsmith & Pan 2008). One practical implication is that consumer reviews on many products can influence their pricing (see Contemporary issue: Good reviews = higher prices).

214

![]() GOOD REVIEWS = HIGHER PRICES

GOOD REVIEWS = HIGHER PRICES

The magnitude of social media’s influence on travel-related decisions is well established; for example, online reviews from reputable websites such as TripAdvisor attract more user trust in regard to hotels than advice from travel agents (Gill 2010). Consumers value such reviews because they are up-to-date and express the opinions of actual product users who do not have a vested interest in making a sale (Ong 2012). Until recently, however, the effect that online reviews have on the prices operators charge for the reviewed services was unclear. The Centre for Hospitality Research at Cornell University investigated this issue by examining data provided by ReviewPro, STR, Travelocity, and TripAdvisor to calculate the return on investment (ROI) from social media reviews of hotels in selected US and European cities (Anderson, Chris 2012). The first finding was that the proportion of consumers who consult TripAdvisor reviews before booking a room is steadily increasing along with the number of reviews that are read. Second, transactional information from Travelocity revealed that a one-point rating improvement on a five-point scale (for example, from 3.9 to 4.9) translates into an ability to raise the room cost by 11.2 per cent without suffering any decline in occupancy rate. Finally, the data from ReviewPro and STR demonstrated that a one per cent increase in a hotel’s online reputation score translates into a 0.89 per cent increase in price, an occupancy increase of 0.54 per cent and a 1.42 per cent increase in revenue per available room. Notably, it wasn’t just online sales that improved, but also reservations made over the phone, lucrative group bookings and corporate negotiated rates. Despite such evidence, many operators do not have clear strategies for influencing or responding to online review information, including whether the hotel should itself maintain a customer review section and/or links to third party travel sites such as TripAdvisor (Ong 2012).

Television

The attraction of television as a media outlet is based in part on its ubiquity and frequency of consumer use, even within less affluent societies. Moreover, television is more effective than any other contemporary mainstream media in conveying an animated, realistic image of a product. To be cost-effective (since television advertising time is relatively expensive), television-oriented advertisements must capture the viewer’s attention quickly (else the viewer may leave to visit the kitchen or toilet) and convey the message within a short period of time (e.g. 30 seconds). Also, they should be timed to optimise exposure to the target audience. For example, it is a wasted effort to target young children during the late evening hours. Similarly, it is critical to match the product with the program. Highly educated viewers, for example, are more likely to watch news programs or documentaries. A major trend is the expansion of television from a small number of standard networks to a large number of specialised networks accessed through cable or satellite. One implication is television’s increasing transformation from a shotgun marketing to a target marketing medium.

215

Radio

As a mass media outlet, radio has long been overtaken by television, but it is still important in Phase Two and Three societies as a promotional device. In Phase Four societies radio remains important as a source of information during work time, either through advertisements or through the pronunciations of popular talk show hosts. From 9 am to 5 pm radio may reach as many potential customers as television. Although less expensive than television, a major disadvantage of radio is the inability to convey visual information. Effective auditory stimuli, however, can evoke desirable and attractive mental images.

Newspapers and magazines

Newspapers and magazines have the advantage of containing messages that can be accessed at any time, and may persist for many years in the form of accumulated or circulating copies. However, this also means that the advertisement becomes obsolete as prices increase and the product is modified. In addition, the images are static and the quality of reproduction can be quite crude in newspapers, even when colour is used. Print media also assumes a literate market, which is a serious impediment in Phase Two and some Phase Three societies. An added complication in highly literate countries is the abundance of newspaper and magazine options, which requires marketers to conduct extensive research in order to identify the most effective target outlets. During 2012, Australians purchased 161 million magazines with a retail value of $843 million, a growing proportion of which is being delivered digitally (Magazine Publishers of Australia 2013).

Brochures

Tourism brochures are perhaps the most utilised form of promotion across the tourism industry and within destinations, and are an important and high-credibility means through which package tours and products within particular destinations are selected (Molina & Esteban 2006). A characteristic that distinguishes brochures from television or other printed media is their specialised nature — they are not provided as an appendage to a newspaper article or a television program, but concentrate 100 per cent on the promotional effort. Brochures are usually printed in bulk quantities, and made available for distribution through travel agencies, tourism information centres, hotels, attractions and other strategic locations, as well as by mail. Brochures can range in complexity from a simple black-and-white leaflet to a glossy booklet, such as those commonly available from large tour operators. Brochures are often retained as trip souvenirs, especially if acquired in the visited destination.

A way of making brochures more attractive and of minimising their disposal is to include practical information (e.g. safety suggestions, directions) and discount coupons or to treat the brochure itself as a means of gaining discounted entry at qualifying attractions. Nevertheless, research among Swiss consumers indicates that they are preferred by older and less educated consumers rather than the more educated potential visitors sought by many destinations (Laesser 2007).

Partnerships

As illustrated by the formation of airline alliances (e.g. Star Alliance and oneworld) and credit cards that feature a particular business or organisation (e.g. the Marriott Rewards VISA card), mutual benefits can result when similar or dissimilar but complementary businesses embark in cooperative product development and marketing on a 216temporary or longer-term basis (Zach 2012). These include exposure to new markets, expanded product packages, greater ability to serve customer needs, more efficient use of resources through sharing, image improvement through association with well-regarded brands and access to partners’ databases and expertise (Morrison 2009).

Partnerships are especially important for small operations that lack the economies of scale to engage in these efforts efficiently and effectively on their own. For example, ‘farm stays’ in certain countries, such as Austria, have formed consortiums of ten or more operators who all benefit from the collective pooling of resources. Another illustration at the multilateral scale is the Mekong Tourism initiative pursued by countries in South-East Asia. Partnerships can also be created between suppliers of products and their customers, as demonstrated by repeat-user programs.

217

CHAPTER REVIEW

Marketing involves communication and other interactions among the producers and consumers of tourism experiences. The marketing of a service such as tourism differs from goods because of the intangibility, inseparability, variability and perishability of the former. These qualities present challenges to managers and marketers in their attempt to match the supply of tourism products with market demand. For example, intangibility means that the consumer cannot directly experience the product before its consumption, while inseparability implies that production and consumption occur simultaneously, thus limiting the scope for employing quality control mechanisms. Because profit margins in the tourism sector are narrowed by high fixed costs, and because demand varies considerably over a daily, weekly, seasonal and long-term timeframe, managers must be aware of the strategies that can be implemented to foster equilibrium between demand and supply. Depending on the circumstances, these involve the reduction, increase or redistribution of supply or demand.