Introduction to tourism management

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

define tourism from a holistic perspective and appreciate its status as one of the world’s most important economic sectors

critique the factors that have hindered the development of tourism studies as an academic field

explain why tourism is currently a field of study rather than an academic discipline

understand the differences between the multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and postdisciplinary approaches

identify the contributions of each the four ‘platforms’ to the evolution and maturation of tourism studies

explain why the growing number of refereed tourism journals is a core indicator of development in the field of tourism studies

compare and contrast the distinctive and mutually reinforcing roles of universities and vocational education and training providers in the provision of tourism education and training.

2

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Tourism is widespread and complex, and sophisticated management is required to realise its full potential as a sustainable economic, ecological, social and cultural force. Complicating this task is its vulnerability to uncertainty, which is demonstrated by contemporary concerns about the global economy and the role of tourism in both affecting and being affected by climate change. This textbook gives students an introductory exposure to tourism that provides a foundation for further informed engagement with the sector, first in the remainder of their tertiary studies and then in their capacity as decision makers. Four themes that inform this textbook under the overarching themes of sustainability and management are:

crisis management/resilience

technology and innovation

inclusivity and diversity

the Asian Century.

This opening chapter introduces the text. The following section defines tourism and emphasises its global and national economic importance. The section ‘Tourism as an academic field of study’ traces the development of tourism studies as an academic focus and considers the factors that have hindered its evolution as such, as well as current indications of its maturation. Finally, we present the themes, outline and structure of the book.

THE PHENOMENON OF TOURISM

THE PHENOMENON OF TOURISM

This book is about tourism management, and it is therefore important to establish what is meant by the term tourism. Most people have an intuitive perception of tourism focused around an image of recreational travel. But how far from home does one have to travel before they are considered to be tourists, and for how long? And what types of travel qualify? Most people would readily appreciate that a family holiday trip qualifies as a form of tourism while the arrival of a boat of asylum seekers does not. But what about academics attending a conference, a Hindu pilgrimage, a group of international students living on the Gold Coast, or participants at the Commonwealth Games? All qualify as ‘tourists’, but challenge our perceptions of what it means to be a tourist. We therefore need to establish definitional boundaries. The questions posed here are beyond the scope of this introductory chapter, but it should be apparent that the definition of tourism depends largely on how we define the tourist, the central actor in this phenomenon (see chapter 2).

DEFINITION OF TOURISM

DEFINITION OF TOURISM

There is no standard definition of tourism. Many definitions have been used over the years, some of which are universal and can be applied to any situation. Others fulfil a specific purpose. Local tourism organisations, for example, often devise definitions that satisfy their own circumstances. The universal definition that informs this text 3builds on Goeldner and Ritchie (2012), who place tourism in a broad stakeholder context. Additions to the original, indicated by italics, further strengthen this holistic perspective:

Tourism may be defined as the sum of the processes, activities, and outcomes arising from the relationships and the interactions among tourists, tourism suppliers, host governments, host communities, and surrounding environments that are involved in the attracting, transporting, hosting and management of tourists and other visitors.

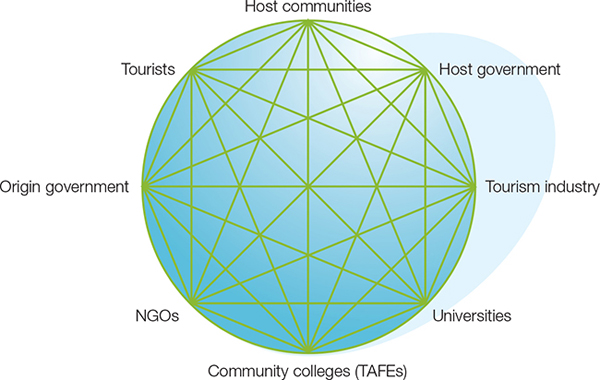

‘Surrounding environments’ include the governments in origin regions, tertiary educational institutions (universities and vocational education and training (VET) providers) and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), all of which are important tourism stakeholders. Figure 1.1 depicts these stakeholders as components of an interconnected network, with possibilities for interaction among any combination of members. Also notable in the expanded definition is the extension of the tourism dynamic to include transportation as well as the management process.

FIGURE 1.1 The tourism stakeholder system

The importance of tourism

The importance of tourism as an economic, environmental and sociocultural force will be detailed in later chapters, but it is useful at the outset to convey a sense of its economic significance. Tourism evolved during the latter half of the twentieth century from a marginal and locally significant activity to a ubiquitous economic giant. In 2014 it directly and indirectly accounted for more than 10 per cent of the global GDP, or approximately $7.0 trillion. This places tourism on the same global scale as agriculture or mining. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) (www.wttc.org), the major organisation representing the global tourism industry, 255 million jobs were dependent on the ‘tourism economy’ in 2012. During that year, for the first time, more than one billion international tourist trips of at least one night were undertaken (UNWTO 2012). Many tourism experts, moreover, believe that the global incidence of domestic tourist travel is anywhere from four to six times this volume. Such 4figures attest to the massive economic impact of tourism and its status as a primary agent of globalisation that involves billions of host–guest contacts and the incorporation of most of the world into an integrated global tourism network.

TOURISM AS AN ACADEMIC FIELD OF STUDY

TOURISM AS AN ACADEMIC FIELD OF STUDY

Tourism has an enormous impact on host destinations as well as transit and origin regions. How much this impact is positive or negative, however, depends on whether tourism is appropriately managed. For a destination, management and planning imply deliberate efforts to control the development of tourism to help fulfil the long-term economic, social, cultural and environmental aspirations and strategic goals of the people living in that destination. This is the essence of the concept of sustainability. If, in contrast, tourism is allowed to develop without formal management, experience tells us that the likelihood of negative outcomes is greatly increased, as later chapters will illustrate. The tertiary education sector has much to contribute to the evolving science of tourism management and planning, and the ongoing evolution of tourism studies is an important development that has paralleled the expansion of tourism itself.

Obstacles to development

The emergence of tourism as a legitimate area of investigation by university academics is a recent development, and one that has encountered many obstacles. It can be argued that this field, like other non-traditional areas such as development studies and feminist studies, is still not given the respect and level of support that are provided to the more traditional disciplines. Several factors that help to account for this situation are outlined here.

Tourism perceived as trivial

Many academics and others in positions of authority have regarded tourism over the years as a nonessential and even frivolous activity involving pleasure-based motivations and activities. Hence, it is not always given the same attention, in terms of institutional commitment, as agriculture, manufacturing, mining or other more ‘serious’ and ‘essential’ pursuits (Davidson 2005). Most tourism researchers can relate tales of repeated grant application rejections, isolation within ‘mainstream’ discipline departments and ribbing by colleagues who believe that a research trip to Bali or Phuket is little more than a publicly subsidised holiday. These misperceptions still occur, but there is now more awareness of the significant and complex role played by tourism in contemporary society, and the profound impacts that it can have on tourists, host communities and the natural environment. This growing awareness is contributing to a ‘legitimisation’ of tourism that is gradually giving tourism studies more credibility within the university system in Australia and elsewhere.

5

Large-scale tourism as a recent activity

Residual tendencies to downplay tourism are understandable given that large-scale tourism is a relatively recent phenomenon. In the 1950s, tourism was a globally marginal economic activity. By the 1970s, its significance was much more difficult to deny, but specialised bodies such as the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) were not yet large or well known enough to effectively spread awareness about the size and importance of the sector. The number, size and sophistication of these organisations have now increased greatly, but most people even today still do not appreciate the actual size or economic influence of tourism.

Bureaucratic inertia and echo effects

Even where there is respect for tourism and an appreciation of its magnitude, the administrative structures of tertiary institutions often make it difficult for new programs and research priorities to be introduced. Universities are bureaucratic institutions characterised by inertia and reluctance to change entrenched structures. When significant change does occur, it is as likely to be as much the consequence of government or legal pressure, interest from large donors, or the arrival of a new vice-chancellor wishing to make their own mark on the institution, as any well-considered examination of societal trends. This has resulted in an ‘echo effect’ whereby universities only started to offer specialised tourism programs in the 1980s, at least decades after its emergence as a major global industry. Even today, many universities are still trying to assess if, where and how tourism should be accommodated within their institutional structures.

Tourism perceived as a vocational field of study

To the degree that tourism in the past was accepted as a legitimate area of tertiary study, it was widely assumed to belong within the vocational education and training system. This reflected the simplistic view that tourism-related learning is only about applied vocational and technical skills training, and that relevant job opportunities are confined to customer service-oriented sectors such as hotels and restaurants. It has historically been easier therefore to incorporate emerging elements of tourism-related learning (such as managerial training) into existing and receptive VET structures than to ‘sell’ them to resistant or sceptical university administrators. Fortunately, TAFE (technical and further education) colleges and universities are now both widely recognised as important tertiary stakeholders in the tourism sector, each making distinctive but complementary contributions to its operation and management.

Lack of clear boundaries and reliable data

The development of tourism studies has been impeded by unclear terms of reference. Aside from the lack of consensus on the definition of tourism, the term is often used in conjunction or interchangeably with related concepts such as ‘travel’, ‘leisure’, ‘recreation’, ‘holiday’, ‘visitation’ and ‘hospitality’. The focus of tourism and its place within a broader system of academic inquiry is therefore not very clear. A similar lack of precision is evident within tourism itself. It is only since the 1980s that the UNWTO has succeeded in aligning most countries to a standard set of international tourist definitions. Yet, serious inconsistencies persist in the international tourism data that are being reported by member states. Attempts to achieve standardisation and reliability among UNWTO member states with domestic tourism data are even more embryonic, making comparison between countries extremely difficult (UNWTO 2012).

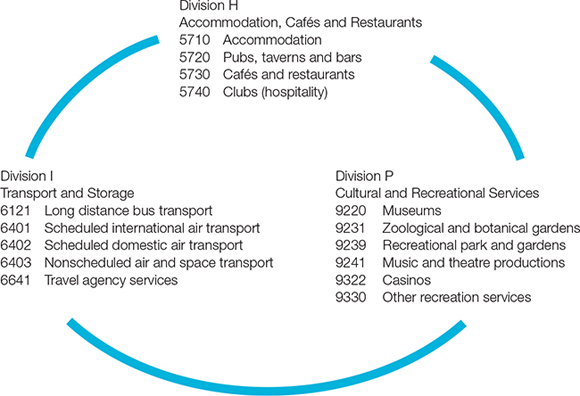

Tourism-related industrial classification codes are also confusing. Finding data on the magnitude of the tourism industry in Australia and New Zealand, for example, is impeded by the lack of a single ‘tourism’ category within the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code used by these two countries (ABS 2006). Instead, tourism-related activities are subsumed under at least 15 industrial classes, many of which also include a significant amount of nontourism activity (see figure 1.2). This system, in turn, bears little resemblance to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) used by the United States, Canada and Mexico, which subsumes tourism under more than 30 individual codes. The tourism ‘industry’, then, loses respect and influence because of official classification protocols that disguise or dilute the sector and divide its massive overall economic contribution into relatively small affiliated industries such as ‘accommodation’, ‘travel agency services’ and ‘recreational parks and gardens’. Leiper (2008) acknowledges this dilution effect and recommends the use of the plural term tourism industries.

FIGURE 1.2 Australian and New Zealand SIC classes related to tourism

Current status

Fragmentation and consolidation

For all the aforementioned reasons, tourism lacks a strong academic tradition. Before the creation of specialised programs and departments, tourism researchers were dispersed among a variety of traditional disciplines, and most notably in social sciences such as geography, anthropology, economics and sociology. Isolated from their tourism colleagues in other departments, tourism researchers could not easily collaborate and generate the synergy and critical mass necessary to stimulate academic progress. However, the gathering of tourism researchers in tourism studies schools or departments has not necessarily generated a more unified approach to the subject. Tourism academics still often pursue their research from the perspective of the mainstream 7disciplines in which they received their education, rather than from a ‘tourism studies’ perspective. Tourism geographers, for example, emphasise spatial theories involving core/periphery, regional or gravitational models, while tourism economists utilise input/output models, income multiplier effects and other econometric theories. This multidisciplinary approach undoubtedly contributes to the advancement of knowledge as tourism researchers come together in tourism departments, but inhibits the development of tourism as a coherent academic discipline in its own right, with its own indigenous theories and methodologies. Such fragmentation, reminiscent of the situation described earlier with respect to tourism-related industrial codes, helps to account for the continued identification of tourism by most tourism academics as a field of study rather than a discipline (Tribe 2010).

Theory is essential to the development of an academic discipline because it provides coherent and unifying tentative explanations for diverse phenomena and processes that may otherwise appear disconnected or unrelated. In other words, it provides a basis for understanding, organising and predicting certain behaviours of the real world and is therefore central to the revelation and advancement of knowledge in any area. Theory often seems to be divorced from the real world, but a grasp of it is essential for those who intend to pursue tourism, or any other area of study, at the university level.

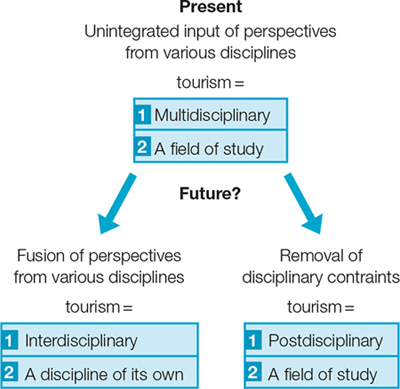

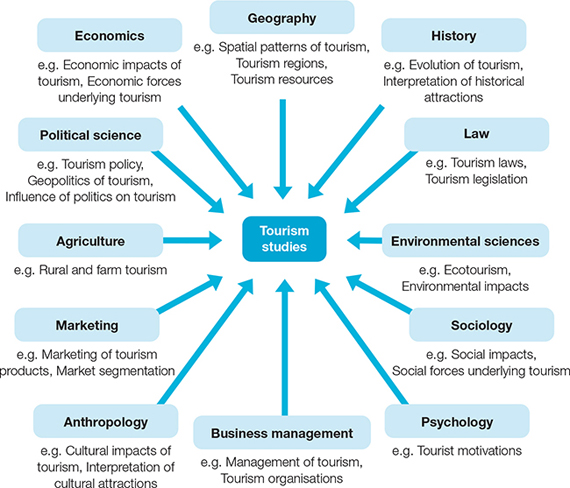

As depicted in figure 1.3, there are indications that the multidisciplinary approach is gradually giving way to a more consolidated interdisciplinary approach in which the perspectives of various disciplines are combined and synthesised into distinctive new ‘tourism’ perspectives. This dynamic is more likely to generate the indigenous theories and methodologies that will eventually warrant the description of tourism studies as an academic discipline in its own right. Others, however, argue that tourism should take a postdisciplinary approach that ‘allows scholars to free themselves from the intellectual shackles applied by disciplinary policing’ (Coles, Hall & Duval 2009, p. 87). By deliberately avoiding the disciplinary stage, researchers could focus on whatever frameworks, theories and methods best help to resolve tourism issues and problems in the real world, retaining only tourism itself as the object of unified and consolidated effort. In this case, it would be appropriate for tourism to continue as a field of study rather than a discipline.

FIGURE 1.3 The evolution of tourism studies

8

Departments and programs

Regardless of the deliberations about theories and disciplinarity, the maturation of tourism studies is indicated by its visibility within university-level education and research in Australia and elsewhere. This is apparent in the large number of specialised departments and programs within Australian and New Zealand universities. Many tourism academics are still based in traditional disciplines such as geography and economics, but an increasing proportion are located within more recently established tourism-related entities and programs. This is extremely significant, given its impact on the field’s visibility and its effect of transforming tourism into a formally recognised and structured area of investigation within the university structure. This process has also played an important role in creating the critical mass of tourism specialists necessary to progress beyond the multidisciplinary stage.

Notably, in Australia it was the newer universities (e.g. Griffith University, La Trobe University), the satellite campuses of older universities (e.g. Gatton Agricultural College of the University of Queensland) and former polytechnic institutions (e.g. RMIT University, Curtin University of Technology), that played a leadership role in the development of such units, as they were less constrained by disciplinary constraints and greater structural rigour of some of the more established institutions. As of 2014, more than half of Australia’s universities hosted departments or programs with a formal tourism component, most commonly within business or management faculties. This holds true for New Zealand’s universities as well. Departments within these faculties that accommodate tourism also typically house complementary or related fields such as hotel management, sport and/or leisure, thus contributing even more to the academic fragmentation and fuzzy boundaries of tourism studies.

Refereed journals

The evolution of tourism studies can also be gauged by the increase in the number of tourism-related refereed academic journals, which consolidate tourism research into a single location and sometimes encourage multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary discourse, depending on the scope of the publication. Because the articles they publish are subject to a normally rigorous procedure of double-blind peer review, refereed academic journals are widely considered to be the major showcase of a field or discipline and the best indicator of its intellectual development (Park et al. 2011). A ‘double-blind’ process means that the author does not know who the editor has approached to assess the submitted manuscript, while the reviewers (two or three are usually employed) do not know the identity of the author.

Disadvantages of refereed journals include:

the likelihood that experts who are asked to referee a submission can identify the author(s) because of their familiarity with research activity in the field, thereby compromising the objectivity of the double-blind review process

the use of ‘academic’ terminology, vocabulary and methods that are not readily understood by the practitioners and destination residents who are most likely to benefit from an understanding of the material

their location within (increasingly electronic) university library collections that cannot easily be accessed by practitioners and residents because of the ‘firewalls’ erected by for-profit publishers.

This latter issue is being resolved in some academic fields through the introduction of open access (or ‘no cost’) journals, though this trend has not yet significantly affected tourism studies. Another problem of the past was the large interval (often 9several years) between the time the research is submitted to the journal and the time of publication (by which time it may no longer be relevant). This is being at least partly addressed by publishers through the increasingly widespread practice of releasing online versions long before the publication of the printed copy. These digital versions are often available just two or three weeks after the final draft of a manuscript has been accepted. The internet also allows supplementary material such as completed questionnaires to be made available to the reader in non-paper formats.

In tourism, only four ‘pioneer’ English language journals existed prior to 1990, three of which (Annals of Tourism Research, Journal of Travel Research and Tourism Management) are interdisciplinary outlets widely regarded as the most prestigious in the field. As of 2014, there were about 60 refereed English-language tourism journals, some of which are combined with related fields (e.g. Journal of Sport Tourism, Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Research). As the amount of tourism-related research increased, many of these journals were established to accommodate specialised topics (e.g. Tourism Economics, Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, Journal of Heritage Tourism) and geographical foci (e.g. Journal of China Tourism Research, Tourism in Marine Environments). Broadly speaking, the topical journals tend to encourage the multidisciplinary approach, while the geographic journals, like the aforementioned pioneer journals, encourage interdisciplinary engagement. It should also be mentioned that there are several hundred refereed tourism journals published in languages other than English, very little content of which is cited in the English language journals.

A sequence of tourism platforms

As tourism has become increasingly visible within the university sector, the perspectives through which academics in the field of tourism studies view the world have also evolved. Jafari (2001) identified four tourism platforms that have sequentially and incrementally influenced and enriched the development of the field.

Advocacy platform

The early literature of the 1960s was characterised by a supportive and uncritical attitude towards tourism, which was almost universally regarded as an economic saviour for a wide variety of communities. Although this advocacy platform can be seen in retrospect as strongly biased and naïve, it must be interpreted in the context of the era in which it emerged. Europe and Asia were still recovering from the devastation of World War II, and the issue of global economic development was focused on the emergence of an impoverished ‘Third World’. As a potential economic stimulant, tourism offered hope to these regions, especially as there were then few examples of unsustainable, large-scale tourism development to serve as a counterpoint.

The prevalent attitude, therefore, was that communities should do all they can to attract and promote tourism activity within a minimally constrained free market environment. The primary role of government, accordingly, is to facilitate tourism growth through pro-tourism legislation and by maintaining law and order. Notwithstanding such ‘anti-regulation’ or ‘anti-management’ sentiments, the 10advocacy platform has made a valuable contribution to the tourism management field by raising awareness of the potential of tourism to serve as an agent of economic development, especially for poverty-stricken regions or places where there are few other viable alternatives.

Cautionary platform

The cautionary platform emerged in the late 1960s as an ideological challenge to the advocacy platform by the political left. Where the advocacy platform endorses free markets and is suspicious of ‘big government’, supporters of the cautionary platform endorse a high degree of public sector intervention and are suspicious of ‘big business’. Tourism’s rapid expansion into new environments, and the Third World in particular, produced numerous tangible examples of negative impact by the early 1970s that called into question the logic of unrestrained ‘mass tourism’ development. The contribution of the cautionary platform to tourism management, therefore, has been to emphasise the need for restraint and regulation. Only the most extreme proponents of this platform have called for the elimination of tourism from particular destinations. Classic and highly politicised works representing this platform include Finney and Watson (1975), who edited a book (A New Kind of Sugar: Tourism in the Pacific) which views tourism as an activity that perpetuates the inequalities of the colonial plantation era. Another is The Golden Hordes: International Tourism and the Pleasure Periphery by Turner and Ash (1975), who compare mass tourists to a barbarian invasion (see chapter 4 for more discussion of the pleasure periphery).

Adaptancy platform

Supporters of the adaptancy platform are ideologically aligned with the cautionary platform; what sets them apart is their proposal of various modes of tourism that they allege to be better ‘adapted’ to the needs of local communities. Specifically, they introduced ‘alternative tourism’ in the early 1980s as a catchphrase to describe small-scale, locally controlled and highly regulated modes of tourism that provide a preferable alternative to mass tourism (see chapter 11). Holden’s examination of alternative tourism options for Asia is a classic application of the adaptancy platform (Holden 1984).

Knowledge-based platform

According to Jafari’s model, the academic study of tourism has moved towards a knowledge-based platform since the early 1990s, in response to at least three factors:

earlier perspectives are limited by their adherence to ideologies of the right or left, which provide only a narrow perspective on a complex issue such as tourism

they are further limited in their emphasis on impacts (advocacy and cautionary) or solutions (adaptancy)

the alternative tourism proposed by the adaptancy platform is a limited solution that is not feasible for the great number of destinations already embedded in mass tourism.

The knowledge-based platform addresses these limitations by shifting from the emotive, limited and ideologically driven perspectives of previous platforms to one that is more objective and aware that tourism of any type results in positive as well as negative impacts, and winners as well as losers. It also adopts a holistic view of tourism as an integrated and interdependent system in which large scale and small scale are both appropriate and potentially sustainable, depending on the circumstances of each particular destination. To use extreme examples, large-scale tourism is appropriate for 11a major urban area such as Shanghai or Sydney, while small-scale tourism is logically more appropriate for Antarctica or south-western Tasmania.

Effective management decisions about such complex systems should be based not on emotion or ideology, but on sound knowledge obtained through the application of the scientific method (see chapter 12) and informed by relevant models and theory. It is through the adherence of tourism academics to the knowledge-based platform, which is strongly associated with the emergence of ‘sustainable development’ and ‘sustainable tourism’ in the early 1990s (see chapter 11), that the field of tourism studies is most likely to achieve interdisciplinarity. An emerging counterargument, however, is that the knowledge-based platform is overly technical and insufficiently informed by the ethics of human need. Accordingly, Macbeth (2005) has called for a new ‘value-full’ platform as the next logical progression in this sequence of perspectives.

Universities and VET providers

The emphasis in this chapter on the evolution of tourism studies within the university sector is in no way intended to imply an inferior role or status for TAFEs or their equivalent. Rather, it is worth reiterating that both play a necessary and complementary role within the broader tertiary network of educational and training institutions. TAFEs and similar institutions have had, and will likely continue to have, a dominant role in the provision of practical, high-quality training opportunities across a growing array of tourism-related occupations. These will increasingly involve not just entry-level training, but also staff development and enhancement.

Universities often provide or at least require similar training credentials (e.g. it is becoming increasingly common for students to earn an advanced diploma in tourism at a VET provider and then transfer to a university to complete a bachelor’s degree in tourism), but their primary responsibilities are in the areas of education and research. Specific roles coherent with the knowledge-based platform include the following (no order of priority is intended):

provide relevant and high-quality undergraduate and postgraduate education, directed especially at producing effective managers, planners, researchers, consultants, analysts and marketers for both the public and private sectors

conduct scientific research into all aspects of tourism

accumulate and disseminate a tourism-related knowledge base, especially through refereed journals, but also through reports and other avenues that are more accessible to practitioners

apply and formulate theory, both indigenous and imported, to describe, explain and predict tourism-related phenomena

critically analyse everything related to tourism

position this analysis within a broad context of other sectors and processes, and within a framework of complexity, uncertainty and resilience

contribute to policy formulation and improved planning and management within both the public and private sectors.

12

CHARACTERISTICS, OUTLINE AND STRUCTURE

This fifth edition, like previous editions, provides university students with an accessible but academically informed introduction to topics and issues relevant to tourism management in the Australasian region. It is not, strictly speaking, a guidebook on how to manage tourism; those skills will evolve through the course of the undergraduate program, especially if the tourism component is taken in conjunction with one or more generic management courses or as part of a management or business degree. No prior knowledge of the tourism sector is assumed or necessary.

Characteristics

This book maintains a strong academic focus and emphasises methodological rigour, objective research outcomes, theory, critical analysis, curiosity and healthy scepticism. This is evident in the use of scientific notation throughout the text to reference material obtained in large part from refereed journals and other academic sources. The inclusion of a chapter on research (chapter 12) further supports this focus. At the same time, however, this book is meant to have practical application to the sustainable management and resolution of real-world problems, which the authors believe should be the ultimate goal of any academic discourse.

FIGURE 1.4 Multidisciplinary linkages within tourism studies

Second, this book provides a ‘state-of-the-art’ introduction to a coherent field of tourism studies that is gradually moving away from a multidisciplinary towards an interdisciplinary or postdisciplinary focus. Either approach is compatible with figure 1.4, which recognises that an integrative and comprehensive understanding of tourism requires exposure to the theories and perspectives of other disciplines and fields (Holden 2005). Prominent among the disciplines that inform tourism studies are geography, business, economics, sociology, anthropology, law, psychology, history, political science, environmental science, leisure sciences, and marketing.

Third, the book is national in scope in that the primary geographical focus is on Australia, yet it is also international in the sense that the Australian situation is both influenced and informed by developments in other parts of the world, and especially the Asia–Pacific region.

Chapter outline

The 12 chapters in this book have been carefully arranged so that together they constitute a logical and sequential introductory tourism management subject that can be delivered over the course of a normal university semester. Chapter 2 builds on the introductory chapter by providing further relevant definitions and presenting tourism within a systems framework. Chapter 3 considers the historical evolution of tourism and the ‘push’ factors that have contributed to its post–World War II emergence as one of the world’s largest industries. Tourist destinations are examined in chapter 4 with regard to the ‘pull’ factors that attract visitors. Global destination patterns, by region, are also described. Chapter 5 concentrates on the tourism product, including attractions and sectors within the broader tourism industry such as travel agencies, carriers and accommodations.

The emphasis shifts from the product (or supply) to the market (or demand) in the next two chapters. Chapter 6 considers the tourist market, examining the tourist’s decision-making process as well as the division of this market into distinct segments. Chapter 7 extends this theme by focusing on tourism marketing, which includes the attempt to draw tourists to particular destinations and products. Subsequent chapters represent another major shift in focus toward the impacts of tourism. Chapters 8 and 9, respectively, consider the potential economic, sociocultural and environmental consequences of tourism, while chapter 10 examines the broader context of destination development. The concept of sustainable tourism, which is widely touted as the desired objective of management, and an appropriate framework for all engagement with tourism, is discussed in chapter 11. Chapter 12 concludes by focusing on the role of research in tourism studies. The textbook, through these 12 chapters, prepares the reader for further university-level pursuit of the topic.

Chapter structure

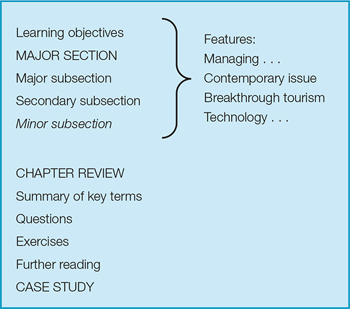

Chapters 2 to 12 are all structured in a similar manner. Each begins with a set of learning objectives that students should achieve at the completion of the chapter. This is followed by an introduction and subsequent text that is arranged by topic area into 14major sections, major subsections, secondary subsections and minor subsections, as per figure 1.5. Four features that support the text through their management implications are dispersed throughout these sections, as appropriate:

the ‘Managing …’ feature focuses on situations related to the chapter theme that have important ramifications for the management of the tourism sector

the ‘Contemporary issue’ feature examines a broader current theme or trend relevant to the chapter

the ‘Breakthrough tourism’ feature identifies new developments that could have important influences on tourism management that are not yet apparent

the ‘Technology …’ feature considers the actual or potential role of technological innovations in shaping the tourism sector.

FIGURE 1.5 Chapter structure

Following a review of the content, each chapter concludes with a sequence of additional features. The ‘Summary of key terms’ defines important concepts and terms in bold type within the chapter. Relevant questions and exercises follow which allow the student to engage and discuss chapter content beyond the level of reiteration. An annotated ‘Further reading’ section suggests additional sources that allow the pursuit of specific topics in greater depth. Finally, each chapter ends with an expanded case study that incorporates multiple themes relevant to the chapter.

15

CHAPTER REVIEW

This chapter defines tourism and provides a preliminary indication of its status as a major global economic activity. The evolution of tourism studies as an emerging field of academic inquiry within the university system is also considered. It is seen that this development has long been hindered by the widespread perception of tourism as a trivial subject and the recent nature of large-scale tourism. Also important are the echo effects produced by the bureaucratic inertia of university administrative structures, the traditional association between tourism and vocational training, the lack of clear definitions and reliable databases, and the diffusion of tourism-related activities among numerous categories of the Standard Industrial Classification code.

Within the contemporary university system, tourism displays the fragmentation of the multidisciplinary approach, which has impeded the development of indigenous theories and methodologies. However, movement toward an interdisciplinary approach indicates greater consolidation, though it is questionable whether tourism will ever become a discipline in its own right. Concurrent with increased research output, tourism has been increasingly recognised in the formation of specialised departments and programs. More than half of Australian and New Zealand universities offer such opportunities, which tend to be newer and less tradition-bound institutions. This has been accompanied by a proliferation of refereed tourism journals, many of which are focused on specific topics or places.

Philosophically, the field of tourism studies has evolved through a sequence of dominant perspectives or ‘platforms’. The advocacy platform of the 1960s contributed to the field by emphasising the role of tourism as an effective tool of economic development. Regarded by many as insufficiently critical, it gave rise to a cautionary platform in the 1970s that identified the potential negative impacts of uncontrolled mass tourism and argued for a high level of regulation. The adaptancy platform that followed in the 1980s proposed small-scale alternative tourism activities that are supposedly better adapted to local circumstances. The current knowledge-based platform arose from the sustainable tourism discourse that began in the early 1990s. It is alleged to be more scientific and objective than earlier perspectives, regarding tourism as an integrated system in which both large and small-scale tourism can be accommodated through management based on sound knowledge. This book provides an academically oriented introduction to tourism management that adheres to these aspirations of the knowledge-based platform.

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

SUMMARY OF KEY TERMS

Academic discipline a systematic field of study that is informed by a particular set of theories and methodologies in its attempt to reveal and expand relevant knowledge; e.g. psychology examines individual behaviour, while geography examines spatial patterns and relationships

Adaptancy platform a follow-up on the cautionary platform that argues for alternative forms of tourism deemed to be better adapted to local communities than mass tourism

Advocacy platform the view that tourism is an inherent benefit to communities that should be developed under free market principles

Asian Century the projected economic and cultural dominance of Asia during the twenty-first century, including its status as a major destination region and source of outbound tourists

Cautionary platform a reaction to the advocacy platform that stresses the negative impacts of tourism and the consequent need for strict regulation16

Double-blind peer review a procedure that attempts to maintain objectivity in the manuscript refereeing process by ensuring that the author and reviewers do not know each other’s identity

Indigenous theories theories that arise out of a particular field of study or discipline

Interdisciplinary approach involves the input of a variety of disciplines, with fusion and synthesis occurring among these different perspectives

Knowledge-based platform the most recent dominant perspective in tourism studies, arising from the sustainability discourse and emphasising ideological neutrality and the application of rigorous scientific methods to generate knowledge so that communities can decide whether large-or small-scale tourism is most appropriate

Multidisciplinary approach involves the input of a variety of disciplines, but without any significant interaction or synthesis of these different perspectives

Postdisciplinary approach advocates moving beyond the theoretical and methodological constraints of specific disciplines so that tourism studies are free to address critical issues in the most appropriate ways

Refereed academic journals publications that are considered to showcase a discipline by merit of the fact that they are subject to a rigorous process of double-blind peer review

Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) a system that uses standard alphanumeric codes to classify all types of economic activity. Tourism-related activities are distributed among at least 15 codes.

Theory a model or statement that describes, explains or predicts some phenomenon

Tourism the sum of the processes, activities, and outcomes arising from the relationships and the interactions among tourists, tourism suppliers, host governments, host communities, and surrounding environments that are involved in the attracting, transporting, hosting and management of tourists and other visitors

Tourism industries a term recommended by some over ‘tourism industry’, to reflect the distribution of tourism activity across a broad array of sectors

Tourism platforms perspectives that have dominated the emerging field of tourism studies at various stages of its evolution; they are both sequential and cumulative

Tourist a person who travels temporarily outside of his or her usual environment (usually defined by some distance threshold) for certain qualifying purposes

QUESTIONS

QUESTIONS

Lack of respect for tourism, or appreciation of its magnitude, are among the factors which have hindered the acceptance of tourism as a legitimate topic of academic inquiry.

What is the best way of changing these perceptions of tourism?

How could the improvement of these perceptions help to overcome the remaining obstacles discussed in the ‘Obstacles to development’ section?

What are the advantages and disadvantages, respectively, of a multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and postdisciplinary approach toward tourism studies?

Why is theory so important to the development of an academic discipline?

How can theory be made more interesting for students and practitioners?

What are the advantages and disadvantages, for students and the field, of incorporating tourism into the same departments as hotel management, sport and leisure studies?

What is the most appropriate ‘division of labour’ between universities and VET providers in terms of the provision of tourism education and training?

What are the advantages and disadvantages, respectively, of integrating or differentiating between the university and VET systems?

EXERCISES

EXERCISES

Randomly select any three stakeholder groups as depicted in figure 1.1.

Describe a tourism management scenario in which these three stakeholder groups would be required to work closely together to solve an important problem.

Prepare a 1000-word report in which you:

Provide an example from your place of residence (country, state, town, etc.) of tourism-related activity (e.g. projects) or discourse (e.g. legislation, reports, letters to editor) that represents each of the four tourism platforms this chapter describes. Clearly show how each example represents its respective platform.

Describe the strengths and weaknesses of each project or discourse with respect to their potential impact on your place of residence.

Identify the stakeholders (e.g. developers, residents, interest groups, administrators) responsible for each of the identified projects or discourses, and speculate why they hold these views.

FURTHER READING

FURTHER READING

Davidson, T. 2005. ‘What are Travel and Tourism: Are They Really an Industry?’ In Theobald, W. (Ed.) Global Tourism. Third Edition. Sydney: Elsevier, pp. 25–31. Davidson argues that not only is tourism not a single industry, but it is counterproductive to treat it as such when attempting to gain respect for the field.

Jafari, J. 2001. ‘The Scientification of Tourism’. In Smith, V. L. & Brent, M. (Eds) Hosts and Guest Revisited: Tourism Issues of the 21st Century. New York: Cognizant, pp. 28–41. This article updates Jafari’s analysis of tourism as having experienced four distinct philosophies or ‘platforms’ in the post-World War II period.

Leiper, N. 2008. ‘Why “the Tourism Industry” is Misleading as a Generic Expression: The Case for the Plural Variation, “Tourism Industries’’ ’. Tourism Management 29: 237–51. This offers another perspective on the status of tourism as a series of discrete industries.

Park, K., Phillips, W., Canter, D. & Abbott, J. 2011. ‘Hospitality and Tourism Research Rankings by Author, University, and Country Using Six Major Journals: The First Decade of the New Millennium’. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 35: 381–416. The rankings of major universities and academics are discussed with respect to tourism research output in influential tourism journals.

Tribe, J. 2010. ‘Tribes, Territories and Networks in the Tourism Academy’. Annals of Tourism Research 37: 7–33. Based on feedback from prominent tourism academics, this paper critically discusses the issue of fragmentation and disciplinarity in the contemporary field of tourism studies.18

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

ABS 2006. Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC), 1993. Catalogue No. 1292.0. www.abs.gov.au. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Coles, T., Hall, C. & Duval, D. 2009. ‘Post-disciplinary Tourism’. In Tribe, J. (Ed.) Philosophical Issues in Tourism. Clevedon, UK: Channel View, pp. 80–100.

Davidson, T. 2005. ‘What Are Travel and Tourism: Are They Really an Industry?’ In Theobald, W. (Ed.) Global Tourism. Third Edition. Sydney: Elsevier, pp. 25–31.

Finney, B. & Watson, K. (Eds) 1975. A New Kind of Sugar: Tourism in the Pacific. Honolulu: East–West Center.

Holden, P. (Ed.) 1984. Alternative Tourism With a Focus on Asia. Bangkok: Ecumenical Council on Third World Tourism.

Goeldner, C. & Ritchie, J. 2012. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies. Twelfth Edition. Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: John Wiley.

Jafari, J. 2001. ‘The Scientification of Tourism’. In Smith, V. L. and Brent, M. (Eds) Hosts and Guests Revisited: Tourism Issues of the 21st Century. New York: Cognizant, 28–41.

Leiper, N. 2008. ‘Why “the Tourism Industry” is Misleading as a Generic Expression: The Case for the Plural Variation, “Tourism Industries’’ ’. Tourism Management 29: 237–51.

Macbeth, J. 2005. ‘Towards an Ethics Platform for Tourism’. Annals of Tourism Research 32: 962–84.

Park, K., Phillips, W., Canter, D. & Abbott, J. 2011. ‘Hospitality and Tourism Research Rankings by Author, University, and Country Using Six Major Journals: The First Decade of the New Millennium’. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 35: 381–416.

Tribe, J. 2010. ‘Tribes, Territories and Networks in the Tourism Academy’. Annals of Tourism Research 37: 7–33.

Turner, L. & Ash, J. 1975. The Golden Hordes: International Tourism and the Pleasure Periphery. London: Constable.

UNWTO 2012. ‘1 Billion Tourists 1 Billion Opportunities’. http://1billiontourists.unwto.org.