7

![]()

What If Choice Is Part of the Test?

But choose wisely, for while the true Grail will bring

you life, the false Grail will take it from you.

—Grail Knight in Indiana Jones and the La& Crusade

In their search for the Holy Grail, both Walter Donovan and Indiana Jones arrived at the Canyon of the Crescent Moon with great anticipation. But after all of the other challenges had been met, the last test involved choice. The unfortunate Mr. Donovan chose first, and in the words of the Grail Knight, “He chose poorly.” The consequences were severe.

In modern society we too must pass many tests, and we too must learn to choose wisely. The consequences are sometimes serious, although hopefully not as profound as for poor Walter Donovan.

In the last chapter we discussed the issues surrounding implementing choice in any fair assessment. I fear that the message I left you with was not sanguine. Allowing an examinee to choose which items to answer on a standardized test seems like a humane way to allow people to showcase their talents most fully. But alas, we saw that too often people do not choose wisely. In fact, those of lesser ability tend to choose less wisely than those who perform better. Thus allowing choice tends to exacerbate group differences.

Is this all there is? Some defenders of choice have come out with another compelling argument, which is sufficiently reasonable that I have chosen to include this small chapter just for its consideration.

The alternative to trying to make all examinee-selected choices within a choice question of equal difficulty is to consider the entire set of questions with choices as a single item.1 Thus the choice is part of the item. If you make a poor choice and select an especially difficult option to respond to, that is considered in exactly the same way as if you wrote a poor answer.

Under what circumstances is this a plausible and fair approach? And, to the point of this chapter, what consequences result from this point of view?

It seems to me that two issues arise immediately:

1. If we want to include the choice as part of the item, we must believe that choosing wisely uses the same knowledge and skills that are required for answering the question. If not, what are we testing?

As a counterexample, suppose we asked examinees in an English literature exam to write an essay on one of two topics. Each topic was written on a piece of paper. One was under a steel dome that weighed 160 pounds, and was quite easy. The other was under an aluminum dome weighing just 5 pounds, but was relatively difficult. It was found that physically stronger examinees (most of whom were men) lifted both domes and then opted for the easier topic. Physically weaker examinees (most of whom were women) couldn't budge the heavy dome and were forced to answer the more difficult question. Since knowledge of English literature has nothing to do with physical strength, making the “choice” part of the question is neither appropriate nor fair.

2. We must believe that the choice is being made by the examinees and not by their teachers. Course curricula are fluid and the choice of which topics the instructor decides to include and which to omit is sometimes arbitrary. If the choice options are of unequal difficulty, and the easier option was not covered in a student's course, having examinee choice disadvantages those who, through no fault of their own, had to answer the more difficult question.

Let us assume for the moment that through dint of mighty effort an exam is prepared in which the choice items are carefully constructed so that the skills related to choosing wisely are well established and agreed by all participants to be a legitimate part of the curriculum that is being tested and that all options available could, plausibly, be asked of each examinee.

If this is all true, it leads to a remarkable and surprising result—we can offer choice on an essay test and obtain satisfactory results without grading the essays! In fact, the examinees don't even have to write the essays; it is enough that they merely indicate their preferences.

EVIDENCE: THE 1989 ADVANCED PLACEMENT

EXAMINATION IN CHEMISTRY

The evidence for this illustration is from the five constructed response items in Part II, Section D of the 1989 Advanced Placement Examination in Chemistry.2 Section D has five items of which the examinee must answer just three.3

This form of the exam was taken by approximately 18,000 students in 1989.4 These items are problems that are scored on a scale from 0 to 8 using a rigorous analytic scoring scheme.

Since examinees must answer three out of the five items, a total of ten choice groups were formed, with each group taking a somewhat different test than the others. Because each group had at least one problem in common with every other group, we are able to use this overlap to place all examinee-selected forms onto a common scale.5 The results are summarized in Table 7.1.

The score scale used had an average of 500; thus those examinees who chose the first three items (1, 2, and 3) scored considerably lower than any other group. Next, the groups labeled 2 through 7 were essentially indistinguishable in performance from one another. Last, groups 8, 9, and 10 were the best-performing groups. The average reliability of the ten overlapping forms of this three-item test was a shade less than 0.60.6

Table 7.1

Scores of Examinees as a Function of the Problems They chose

Suppose we think of Section D as a single “item” with an examinee falling into one of ten possible categories, and the estimated score of each examinee is the mean score of everyone in his or her category. How reliable is this one-item test?7 After doing the appropriate calculation we discover that the reliability of this “choice item” is .15. While .15 is less than .60, it is also larger than zero, and it is easier to obtain.

Consider a “choice test” built of “items” like Section D, except that instead of asking examinees to pick three of the five questions and answer them, we ask them to indicate which three questions they would answer, and then go on to the next “item.” This takes less time for the examinee and is far easier to score.

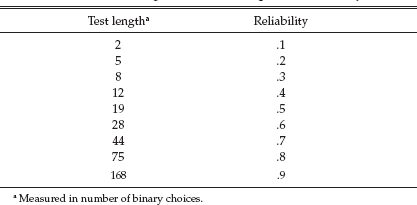

TABLE 7.2

Guide for Building a choice Test of Specified Reliability

Of course with a reliability of only .15, this is not much of a test. But suppose we had two such items, each with a reliability of .15. This new test would have a reliability of .26. And, to get to the end of the story, if we had eight such “items” it would have a reliability of .6, the same as the current form.

Thus, if we truly believe that the act of choosing is accessing the same key skills and knowledge as the specific questions asked, we have found a way to measure those skills with far less effort (for both the examinee and the test scorer) than would have been required if the examinee actually had to answer the questions.

Such a test need not be made of units in which the examinee must choose three of five. It could be binary, in which the examinee is presented with a pair of items and must choose one of them. In such a situation, if the items were constructed to be like the AP Chemistry test, the number of such binary choices needed for any prespecified reliability is shown in Table 7.2.

Of course all of these calculations are predicated on having items to be chosen from that have the properties of those comprising Section D for the 1989 AP Chemistry examination: The items must vary substantially in difficulty, and this must be more or less apparent to the examinees, depending on their proficiency.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

How much information is obtained by requiring examinees to actually answer questions, and then grading them? This effort has some reward for the AP Chemistry test, where the constructed response section is analytically scored. But how much are these rewards diminished when the test's scoring scheme is less rigorous?

Table 7.3 shows the reliabilities for the constructed response sections of all Advanced Placement tests. Note that there is very little overlap between the distributions of reliability for analytically and holistically scored tests,8 the latter being considerably less reliable. Holistic, in this context, means that the scorer, after reading the examinee's response, assesses its value as a whole, rather than by measuring different aspects separately and adding them up in some fashion. Chemistry is a little better than average among analytically scored tests with a reliability of .78 for its constructed response sections.

It is sobering to consider how a test that uses only the options chosen would compare to a less reliable test (i.e., any of the holistically scored tests). The structure of such a choice test might be to offer a set of, say, ten candidate essay topics, and ask the examinees to choose four topics that they would like to write on. And then stop.

It is not my intention to suggest that it is better to have examinees choose questions to answer than it is to actually have them answer them. I observe only that if the purpose is measurement, a great deal of information can be obtained from the choices made. Moreover, one should feel cautioned if the test administration and scoring schema that one is using yields a measuring instrument of only about the same accuracy that would have been obtained ignoring the performance of the examinee entirely.

This is what I like best about science. With only a small investment in fact, we can garner huge dividends in conjecture.

TABLE 7.3

Reliabilities of the constructed Response Sections of AP Tests

1 Using the currently correct jargon this “super item” should, properly, be called a testlet.

2 A full description of this test, the examinee population, and the scoring model is found in Wainer, Wang, and Thissen 1994.

3 This section accounts for 19 percent of the total grade.

4 The test form has been released and interested readers may obtain copies of it with the answers and a full description of the scoring methodology from the College Board.

5 We did this by fitting a polytomous IRT model to all ten forms simultaneously (see Wainer, Wang, and Thissen 1994 for details). As part of this fitting procedure we obtained estimates of the mean value of each choice group's proficiency as well as the marginal reliability of this section of the test.

6 Reliability is a number between 0 and 1 that characterizes the stability of the score. A reliability of 0 means that the score is essentially just a random number, having nothing whatever to do with your proficiency. A reliability of 1 means that the score is errorless. Most professionally built standardized tests have reliability around .9. The reliability of .6 on this small section of a test is well within professional standards.

7 We can calculate an analog of reliability, the squared correlation of proficiency (θ) with estimated proficiency ![]() from the between group variance [var(μi)] and the within group variance (which is here fixed at 100). This index of reliability,

from the between group variance [var(μi)] and the within group variance (which is here fixed at 100). This index of reliability,

![]()

is easily calculated.

8 The term holistic is Likely derived from (after Thompson 1917) “what the Greeks called ![]() . This is something exhibited not only by a lyre in tune, but by all the handiwork of craftsmen, and by all that is “put together” by art or nature. It is the “compositeness of any composite whole”; and, like the cognate terms

. This is something exhibited not only by a lyre in tune, but by all the handiwork of craftsmen, and by all that is “put together” by art or nature. It is the “compositeness of any composite whole”; and, like the cognate terms ![]() or

or ![]() , implies a balance or attunement.”

, implies a balance or attunement.”