Producing involves bringing everything together for a successful production. The discipline of thorough preproduction planning cannot be emphasized strongly enough. The success of every production is determined to a very great extent by the way problems are anticipated before they occur. The techniques needed for producing include a great deal of organizational ability and attention to detail. With experience, successful producers develop a feel for the type of material that has the potential for success. They also develop a good instinct for people that enables them to hire the appropriate cast and crew members who will bring the project to fruition.

Types of Producers

The nature and scope of a project determine how many people are involved in producing. A short film planned for YouTube might have one “guiding light” who produces, writes, and hosts the show and handles the expenses out of his or her own pocket. A network reality series might have one or more executive producers, one or more producers, a line producer, and a number of assistant and associate producers.

Sometimes, producer credits are given to people who are not involved in the start-to-finish production process but who render some special service, such as introducing an executive to someone who provides funding for the show. Sometimes, writers are given producer credits so that they can earn extra money in the form of residuals when the program is rerun. The Producers Guild of America is the professional organization for producers in motion pictures, television, and new media.

Executive Producers

Executive producers are generally people who oversee a number of different productions. If an independent production company produces a show or series, the owner of the company might take an executive producer credit on all the productions from that company (e.g., the CSI family of shows). Generally, the executive producer makes the deals with the networks and makes decisions regarding the overall scope and direction of a series. In a similar vein, if the network itself produces its own programs, it has employees who serve as executive producers and oversee several projects. Your instructor probably serves as the executive producer for your class projects.

Producers

Producers, as opposed to executive producers, have a more hands-on role in a series or program. A producer is involved in hiring cast and crew and might be the one who came up with the original idea and secured the funding. Although producers are not always on the set once production begins, they keep watch over the production’s progress and make decisions related to schedules and money. They also handle legal and promotional matters, such as clearing copyrights and making sure that photos are taken and sent to publicity outlets.

For news programs, producers have a slightly different role. There is usually a producer for each newscast who decides which stories should be aired. This person is in the control room during the newscast and is involved in making decisions while the program is in progress. For example, the news producer would make the decision to air a breaking news story instead of a planned story. Additionally, a newscast might have a segment producer assigned to each news package that airs, though in today’s world of converging technology and shrinking budgets, most reporters serve as their own segment producers.

Associate and Assistant Producers

Many productions have associate or assistant producers: people who help producers by assuming responsibility for one or more producing tasks. For example, a game show might have one assistant producer whose job is to acquire free prizes for contestants, while another assistant producer is in charge of screening potential contestants. In news, associate producers might rewrite wire copy. Whether someone is an assistant or associate producer does not relate as much to the job as it does to his or her level of experience and skill. An associate producer is paid more than an assistant producer, so people often start out as assistant producers and move up to associate, then to producer.

Line Producers

Some productions have a line producer, also known as a supervising producer. This person represents the producer and is on the set each day making sure that all is progressing properly. Specifically, the line producer ensures the TV episode or movie will finish on budget and in time for its scheduled airing or release.

Line producers sometimes work closely with unit production managers (UPMs). UPMs deal specifically with aspects of budgeting and scheduling equipment. Sometimes they are hired by the line producer; other times they are hired by the producer; and often they are employees of a production facility. Occasionally, a show operates with a UPM but not a line producer.1

Hyphenates

Sometimes people are hyphenates. They take on multiple roles, such as producer-director, producer-writer, or even producer-writer-director. There are advantages and disadvantages to handling a number of different roles. Most people evolve into hyphenates because they want creative control. A writer who is displeased with how a director interprets his or her script might decide to become the director for the next script. Directors who feel that cost-conscious producers unnecessarily curtail them might want to make their own decisions about how to prioritize spending. Producers who work hard to develop a project and raise the funding might want to ensure that their vision is carried out during the production phase.

Although being a hyphenate can provide greater creative control, it is also more work. Given the time pressures of most TV productions, one person can become exhausted trying to polish a script, find Civil War–era guns, and plan camera angles all at one time. Also, few people have all the aptitudes necessary to undertake multiple jobs. Someone who is highly skilled in getting the best performance from actors might not be equally skilled in handling financial statements. Multiple people with different abilities and points of view who work together harmoniously can enrich a production. Conversely, one person who is given too much responsibility can flounder—or become an egomaniac. Often, the reasoned judgment that comes from bouncing ideas off others leads to a richer end product. (See Figure 3.1.)

Regardless of how the producing chores are divided, somewhere along the way they involve idea generation, budgets, personnel, schedules, legal considerations, promotion, and evaluation.

Budgets

You may not think much about budgets at this point, especially if your production’s monetary needs are small and you have access to free equipment via your department and unpaid student talent. But in the reality of production, budgets are very important. A producer who spends over budget is not likely to stay employed. Graduating students who understand the procedures of budgeting will be considered more valuable than graduates who have mastered only creative or technical talents. For that reason, it behooves you to practice budgeting by figuring out what it would cost to produce your class projects if you were doing them in the professional world.

Costs of Productions

Production expenses are categorized as either above-the-line or below-the-line. The above-the-line costs are the salaries and benefits of the top creative people who make the key decisions and shape the production: producers, directors, writers, name talent, and sometimes others who are well-known for their crafts and can negotiate top salaries (e.g., top cinematographers and sound designers). Below-the-line costs are for both people and fixed costs, including the salaries and benefits of the technical crew, rental of sound stages and equipment, supplies such as scenery and makeup, and other non-creative costs, such as craft services (food).

Costs vary greatly depending on many factors, including whether the crew is union or nonunion, the recognition value and reputation of the talent, the length of the production, the number of complicated effects needed, the part of the country or world in which the production takes place, and whether the equipment and facilities being used belong to the production company or are rented from other companies.

Pay Rates

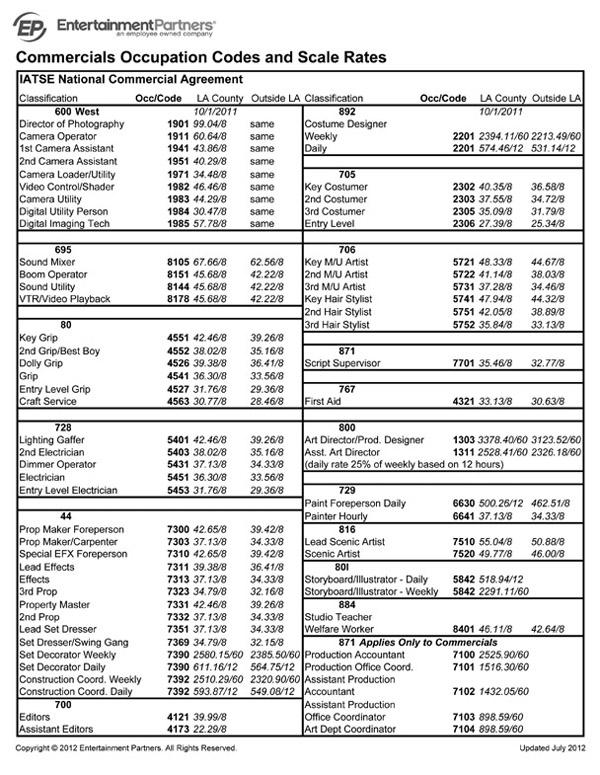

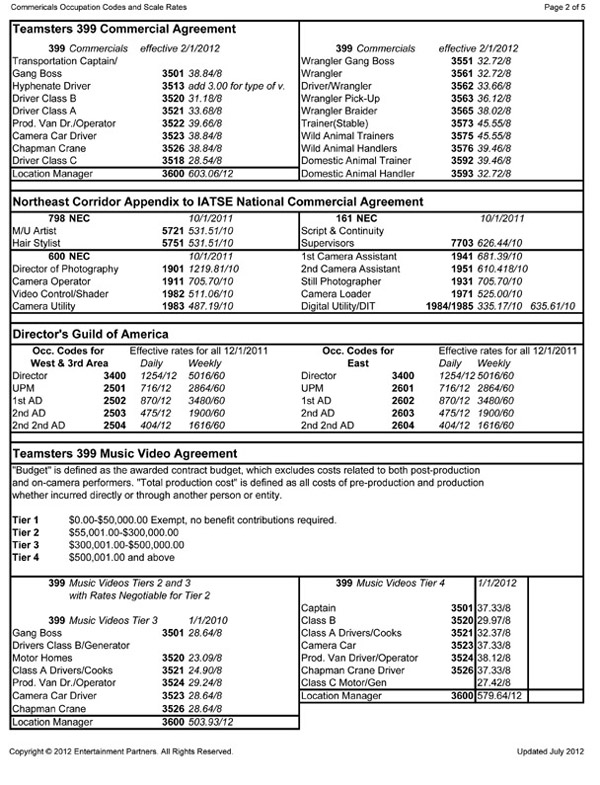

Most major production companies, most networks, and some local stations are unionized and agree to pay at least the minimum cast and crew wages stipulated by the various unions. Two of the unions that represent technical personnel are the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) and the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States, Its Territories and Canada (IATSE). Four guilds that represent above-the-line people are the Producers Guild of America (PGA), the Directors Guild of America (DGA), the Writers Guild of America (WGA), and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA).

Shoots that are nonunion can pay whatever the payers and payees negotiate. Note that the unions and guilds fine their own members if they work for less than union rates. However, student producers and other low-budget or no-budget producers can request waivers from the unions to secure union employees for less than union wages, thereby avoiding the fines. At the higher end of the budget scale, people whose skills are highly prized can demand much more pay than that stipulated by the union and guild minimums.

The television industry tends to hire freelance cast and crew by the hour, day, or project. (See Figures 3.2a and 3.2b.) However, sometimes, people are hired on a more permanent basis, usually referred to as staff positions. A local station, for example, might hire a news producer to work with the local news day after day, year after year. That same station might have a staff director who directs a public-service show one day and a sports program the next. Staff people usually receive less pay per hour than freelance people, but they are assured of steady employment and benefits, while their freelance counterparts must constantly seek new jobs.

Facilities and Equipment

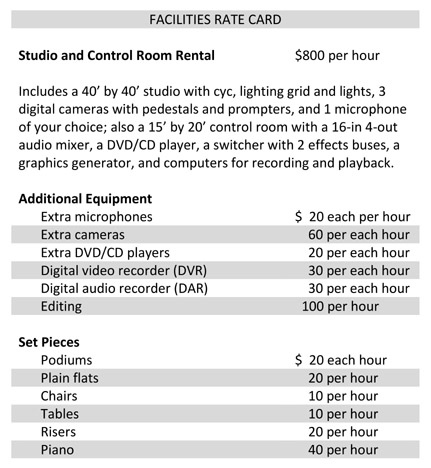

Facilities and equipment are major below-the-line costs of production. If a program is produced in house—that is, within a production facility that has its own studio and equipment—the cost could be considered next to nothing, because everything that is needed is already in place. However, the facility must be maintained, and equipment must eventually be replaced, so even a local show produced at a local station is usually “billed” in-house for use of the facilities.

When a producer rents an outside facility, costs are real and can be easily budgeted. Most organizations that rent out studios or equipment have a rate card listing the cost for a fully equipped studio (“full facilities” or “full facs”) or for the various pieces of equipment that the client might wish to use. The rate card shown in Figure 3.3 lists the costs for a studio with three cameras and other commonly used production equipment, as well as the rates for additional equipment. (Rates for portable equipment and editing are given in Chapter 12.) Again, you can use these numbers for constructing practice budgets, keeping in mind that the numbers vary greatly depending on the city in which the production takes place.

Supplies are figured at what they actually cost. If the production calls for a wig, the producer (or assistant producer) must locate an appropriate wig (often with the help of the Internet) and find out how much it costs. Craft services are another supply cost, as are transportation, real props (not standard set pieces provided in the studio rental fee), and anything else necessary for a production.

Constructing and Adhering to the Budget

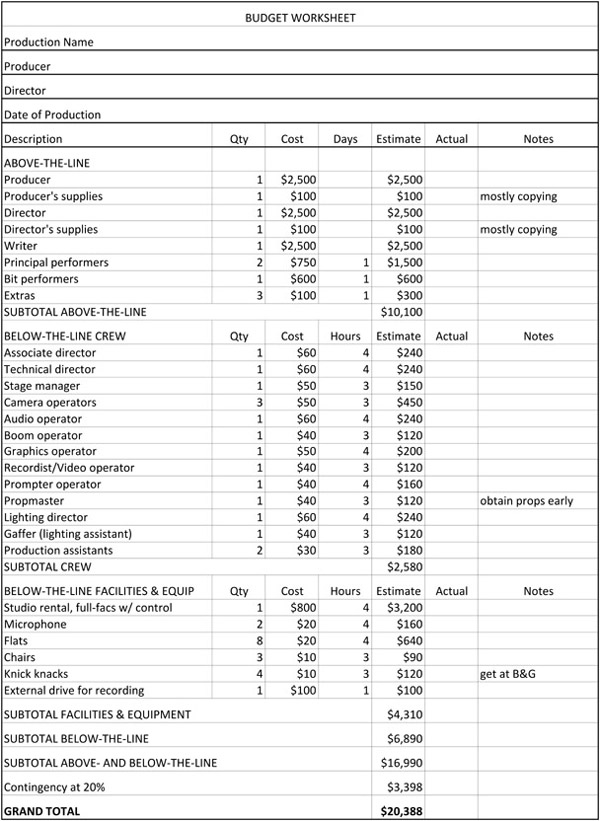

Once all the cost information has been gathered, the producer must construct the budget. It is laid out with the above-the-line costs separated from the below-the-line costs. After all the costs have been listed and totaled, a contingency of 15 to 20 percent is added to cover the unexpected.

Figure 3.4 shows a budget worksheet for a typical TV production. You can use this form to devise theoretical budgets for your productions, or you can make up your own layout. Many different budget forms are used in the industry. Some list the associate director as above-the-line rather than below-the-line. Not all of them have one column for cost estimate and another column for actual cost, but comparing estimates with the actual costs is good experience for someone just learning to budget. Undoubtedly, there will be things or people you need for your productions that are not listed on this budget. Doing a little research to discover their costs is another good way to learn the intricacies of budgeting.

Computer spreadsheets are particularly helpful for budgeting. They allow producers to determine what costs would be under various circumstances— with three cameras versus four cameras, hiring two different audio operators versus paying one audio operator overtime, with and without the scene that requires renting a helicopter. Although any spreadsheet can be used to prepare a budget, those made especially for the entertainment industry are helpful because they contain film and television terminology. The program most frequently used is Movie Magic Budgeting, which is available through Entertainment Partners.

Budget Overruns

If too much money is being spent, the producer is the one who must solve the problem. At times the producer can raise additional money to cover the shortfall. Sometimes, the producer can convince the director to work faster. Other times, some element of a program must be cut to save money.

Budgeting is a difficult process. Costs must not be exaggerated, or people will not be willing to undertake the production. But sufficient money must be provided so that the program can be successful. As money becomes tighter, more care must be given to drawing up and adhering to the budget.

Personnel

In addition to overseeing the development of the script and budget, another major duty of the producer is hiring people. The most important person the producer hires is the director. Sometimes, the producer bows out of the hiring process once he or she hires the director, allowing the director to hire the rest of the cast and crew. Of course, if the producer, director, and crew members are all on staff at a production facility, no actual hiring takes place, but the producer might lobby to have the most appropriate (and skilled) of the available directors and crew members assigned to the project.

Casting

If the project is a drama, sitcom, or web series, casting is crucial, and producers often want to be involved. The usual procedure is for the producer and / or director to draw up a list of the characters, along with their physical and psychological traits. (Often this is taken from the treatment or script.) This list is given to various agents, who then select actors they represent and send them to an audition, where they read lines of the script. Then the director, producer, and others who have a vital interest in the production select the cast members. Big-name actors usually do not audition; the producer and director know of their talents and negotiate with their agents to bring them on board. Sometimes, casting agencies are hired for productions with large casts, such as made-for-TV movies. The director might be involved with hiring the principal actors, but the casting agency alone fills the minor parts.

Although dramas present the greatest challenges for finding talent, other types of shows also involve hiring or selecting talent. For example, great care goes into selecting contestants for game shows. The number of people wishing to try their luck far exceeds the number needed, so producers and associate producers look for people who are lively or unusual and who have the potential to perform well when the cameras are on. Reality-show producers are interested in the potential dynamics among the people they select. Talk-show producers try to line up people who are well-known or eccentric and who will interact well with the host or hostess. Public-affairs producers look for people with something to say who can present their points in a dynamic (or at least not boring) manner.

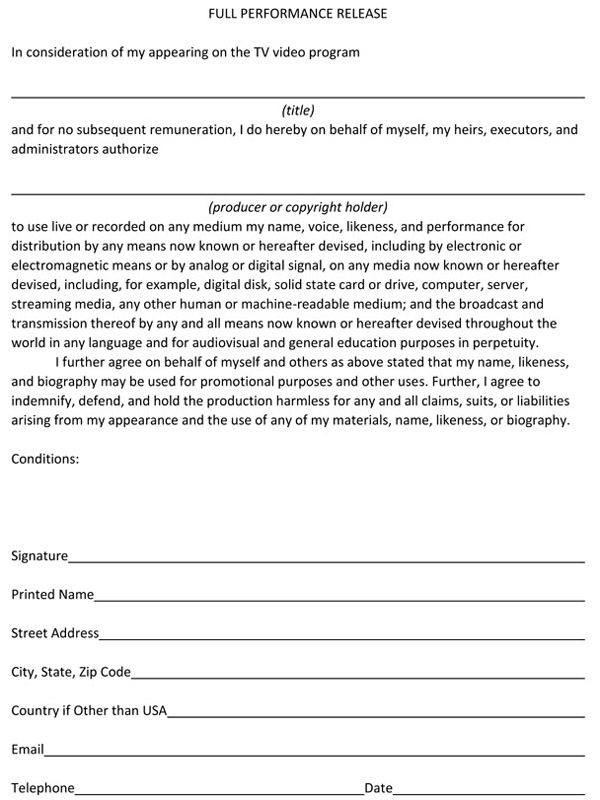

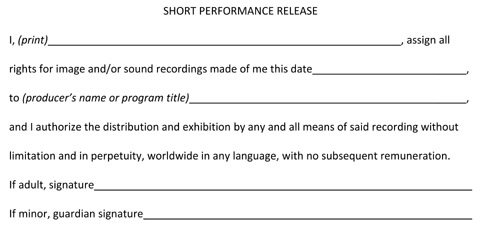

Actors who appear on dramas or sitcoms sign contracts that stipulate how much they will be paid and what their general obligations and working conditions are. Nonprofessionals should also be asked to sign performance releases so that they cannot come back later and ask for money or other privileges. (See Figures 3.5a and 3.5b.)2 One student producer learned this lesson the hard way. A sword swallower appeared in his student production, and he neglected to get the proper release form signed. Later, the production aired on a cable-TV public-access channel, and the sword swallower, thinking the student was making huge amounts of money distributing the video, sued for $100,000 in retroactive pay and residuals. Although the student managed to avoid paying the sword swallower, he had to hire and pay a lawyer to fight the suit.

Crew Selection

The producer hires the unit production manager and assistant producers, if needed. She or he might also be involved with selecting camera operators, scenic designers, makeup people, and the like. One of the most important considerations is gathering a group of people who will work harmoniously as a team. Frequently, producers and directors seek out people they have worked with in the past because they share a common approach to and understanding of the TV production process. This makes it hard for new people to break into the business, but it usually ensures a successful production. If talent or crew must be brought in from a great distance, if the production lasts for many hours, or if any of the shooting is done at a remote location, then the producer must make arrangements for transportation, lodging, and meals.

Schedules

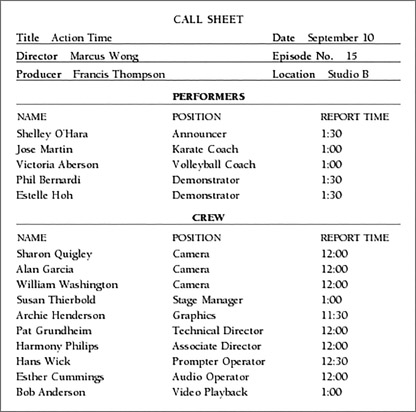

Scheduling is another part of the producer’s duty. Sometimes, this is relatively easy. An ongoing series produced in a studio is likely to record at the same time each day or each week. The set is the same each time, and, for the most part, the cast and crew remain unchanged. For such productions, the producer usually posts a call sheet on the studio door or e-mails it to all the cast and crew. (See Figure 3.6.) This lists the time that everyone is to appear and gives a general idea of what will be shot. The time may generally be the same from week to week, but the call sheet takes into account aberrations. For example, if a complicated makeup job is called for in a particular episode of a series, the person being made up and the makeup person need to report earlier than usual.

Scheduling is more complicated for a studio show that is produced only once. The producer must find a time or times when all the performers are available, often a difficult task because people appearing on a one-time-only basis are likely to have other obligations. The producer must also make sure that a studio is available at a time when all the performers are available. If a producer wants a particular crew member, such as a certain audio operator, that further complicates the scheduling process. Many producers like to work with timelines that list everything that needs to be done for a production according to when it needs to be completed—a month before production, a week before, a day before, or the day of production.

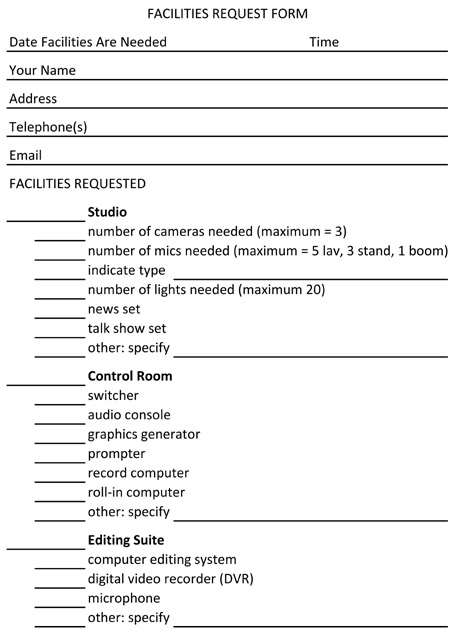

Whether the programming is ongoing or one time only, a producer or assistant needs to fill out a facilities request form (often abbreviated as FACS) reserving specific equipment or a specific studio and control room. (See Figure 3.7.) Such a form is needed (even in university settings) so that people don’t show up and find others using the equipment they need. The specific FACS request depends on the budget; full FACS are for larger budgets, and individual items are for smaller budgets.

Shoots that cover real events, such as news and sports, have their schedule set for them. The equipment and crews must be available and in place when the event takes place. The scheduling is easiest if the time of the event is known well in advance. However, news, by definition, does not occur that way. For this reason, most stations and networks have equipment dedicated to the coverage of news events.

Scheduling field production and remotes is quite complicated. Multiple locations add to the complexities associated with having cast and crew available. Also, being a long distance from the studio makes it difficult or impossible to return for something that was forgotten. For these reasons, producers draw up thorough breakdown sheets, shooting schedules, and stripboards that list all the elements needed at each location (see Chapter 12). If a studio shoot is particularly complicated, the forms used for field production might be used in the studio setting to ensure that everything goes smoothly.

Legal Considerations

It is the producer’s responsibility to oversee legal procedures related to a production. If problems arise, a lawyer should be brought in to deal with them. Sometimes, producers have law degrees because legal considerations have become a larger and larger part of the producing job.

Copyright Clearance

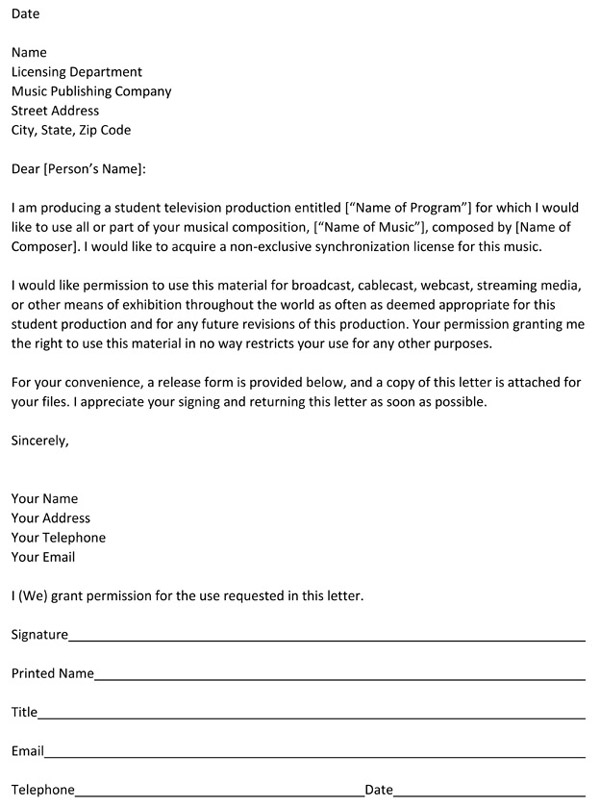

Copyright is one of the major legal considerations. Nothing that has been copyrighted (e.g., a poem, photograph, music, film footage) can be used on a show unless the copyright owner grants permission. The U.S. Copyright Office provides information about the kinds of materials that can be copyrighted and require permission to use. Obtaining permission involves sending written requests via e-mail, fax, or mail to copyright holders and then keeping careful track of what has and has not been cleared. (See Figure 3.8.) Sometimes, copyright holders specify particular stipulations, such as special wording in a credit at the end of the program, and many charge a fee. Producers must make sure these requirements are executed.

The most commonly used copyrighted material in programs is music. Some TV stations and networks pay music licensing companies (ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC) for the right to use music represented by those companies, which includes most popular music. Most independent productions (including student productions that are going to be shown outside the classroom) must clear copyright or use material that is not copyrighted.

Clearing copyright can be a difficult chore for the producer. Often, determining who owns a copyright requires extensive research, although online databases have made this task much easier. With music, the copyright holder might be the composer, the arranger, the publisher of the sheet music, the record company, or some combination of these. Usually, once they are contacted, they want money, so copyright clearance can be expensive.

Some music may be used without copyright clearance and for free. One category of copyright-free music is music that is old enough to be in the public domain. Usually, this means the composer has been dead at least 50 years; still, a particular arrangement of a public-domain song can be copyrighted, and the rights to that arrangement might not be in the public domain. A second type of free music is stock music from a music library. Most production houses, and maybe your university, purchase royalty-free music libraries. These require a one-time purchase fee and sometimes an annual renewal fee, but, once the fee is paid, all the music in that collection may be used in productions with no additional fees or copyright clearances.

Another way to acquire music without searching for and obtaining permission from a copyright holder is to have music composed specially for the production. This can be expensive if the composer is to be paid. However, student productions have an advantage: Universities usually have music students eager for composing experience in return for a production credit. In addition, services exist that provide copyright-cleared music very inexpensively, and computer programs are available that include snippets of copyright-cleared music that you can piece together easily to create your own music. RoyaltyFreeMusic.com lists numerous sources for obtaining copyright-cleared music.

The producer’s problems are similar with regard to video footage. If the opening credits require a shot of an airplane taking off, you cannot simply copy a takeoff from a movie you have seen on TV and use it without permission. You could have someone take portable equipment to the nearest airport and get the shot, or you could acquire it from a company that supplies stock footage, such as Stockfootage.com or Fotosearch.com. The price is high (a minimum fee of $300 is not uncommon), but these companies have video and photos that cover a wide variety of situations. You might also look at videos that others have posted online, such as on Vimeo or YouTube, and, if you see something you’d like to use, you can contact that person individually for permission and to ask for a high-quality, clean copy of the footage.

You might also find video and photos you can use in the public domain. As noted above, this usually means the creator has been dead for at least 50 years. Additionally, any content created by a government agency (federal, state, local) is in the public domain because the public’s tax dollars paid for the crew and materials that recorded the footage or image. The Library of Congress is the official repository of government archives, so that’s a good place to start a search for government-created content. Moreover, the Creative Commons has become a popular place for users to share content freely. Anyone can upload video clips, photos, images, or other materials and share them freely with the world. Often, the copyright holder requests credit for his or her creation if it is used in a production, book, article, exhibit, and so on. Sometimes, a fee is involved. As with any material that seems to be free out there on the Internet of things, in the absence of a statement stating you may use the content freely, you should contact the copyright holder and ask for permission.

Permission to use written material (such as poems, stories, or charts) can usually be obtained from the publisher of the publication in which it first appeared. In contrast, permission to use a painting that appears in an art book might require permission of the artist, the photographer who took the picture of the painting, the publisher of the book, the museum that owns the painting, or some combination thereof. For big budget productions that use a lot of copyrighted material, a person or agency might be hired to obtain the rights to everything. The upfront cost of assuring copyright clearance can save lots of money by preventing expensive lawsuits down the road. For low-budget and no-budget productions, it is best to search for public domain material, royalty-free material, or friend material—ask talented colleagues to create the material for you (e.g., music, artwork) in exchange for pizza and a credit.

Other Legal Issues

U.S. Congress, the Federal Communications Commission, and state and local governments pass laws and create regulations that affect TV production. For example, while the First Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees, among other things, freedom of the press (understood to mean all media, not just traditional media that “pressed” ink onto paper), it is legal for someone who feels he or she has been libeled or slandered by something shown on TV or in other media to sue a station or network. News producers must be particularly careful to make sure reporters have checked facts so that a person’s character is not falsely defamed. There also are laws related to invasion of privacy, most of which state that a person has a right to be left alone. Again, these laws affect how news is gathered, particularly in relation to hidden cameras and microphones. Legal considerations of privacy can also come into play in dramatic projects. For example, a person has the right to sue a network planning to make a movie about his or her life if the person does not want the movie made.

Laws governing indecency and obscenity affect costuming and nuances of scripts for drama and comedy programs. During election periods, regulations govern the appearance of political candidates on TV. Producers, with the aid of legal counsel, are the ones who have the responsibility to make sure programs do not run afoul of the law.

Record Keeping

The producer must keep careful records, including legal documents, receipts for all purchases, logs of any damage to sets or locations and any injuries to talent or crew, and other paperwork that is generated during preproduction, production, and postproduction. This paperwork is necessary for a number of reasons. First, if the producer leaves and a new producer is hired, he or she will have the necessary information to continue production. Second, detailed records supply the cast and crew with specifics so that they can do their jobs correctly. Third, some of the paperwork is used for tax purposes. Fourth, some is needed in case of (or, hopefully, to prevent) lawsuits.

Computers make record keeping relatively easy. To the extent possible, the producer should create both an electronic and a hard-copy folder for each production. In addition to the items mentioned above, this folder should contain a copy of the treatment or proposal; the budget; the script; the various schedules, contracts, and releases; and a list of cast and crew that includes their contact information—e-mail addresses, cell phone numbers, backup numbers, and so on.

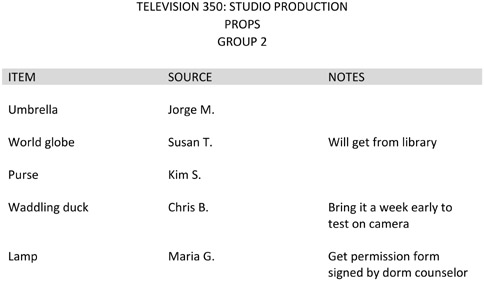

Because one of the duties of the producer is to make sure all elements of the program are in the right place at the right time, producers usually make and double-check many lists. The types of lists vary from production to production. A drama needs lists that detail costumes, sets, props, and who is responsible for each. (See Figure 3.9.) An ongoing talk show needs a list of upcoming guests and dates when they are scheduled to appear. A game show needs a list of prizes that have been or may be acquired for free. A producer and the people who work for a producer must be very organized. Production is expensive, and forgetting about a simple prop can lead to cast and crew standing around with nothing to do—a very expensive proposition indeed.

Promotion and Evaluation

Promotion has become much more important than it used to be. When there were fewer networks, it was easier for people to find shows, so the shows did not need to be promoted as heavily. Now it is possible for an excellent program to get lost in the crowd. Promotion used to be handled primarily by the promotion department of a network or station, but now people involved with a production must do some of their own promotion. Producers usually see that photographers are on the set to take pictures to be used in advertisements and press kits. Sometimes, they write promotional copy or oversee the creation of promotional ads that are aired on the network or on Internet sites such as YouTube. Often, producers oversee the creation of a website that is launched in conjunction with a program. They must integrate the website with the program and make sure that anything mentioned as being on the website is actually there. If audience members are asked to e-mail or text or call the program, the producer must assign someone to respond to the messages. Additionally, a great deal of promotion occurs with social media, so producers have to make sure accounts are created, maintained, and updated on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and whatever else is “hot” in the coming years.

Once a program is finished, the producer has another function: evaluation. The program should meet its goals. For network TV, the main evaluation process is ratings. A series with high ratings stays on the air; one with low ratings is canceled. Other types of programs need much more sophisticated evaluation. The producer of a cooking show designed to show people how to bake a cake should test participants after they have viewed the program to see if they really can bake the cake. Demographic studies should be undertaken to make sure a program designed to appeal to 8- to 11-year-olds is actually watched by that age group. Web-based material, either stand-alone programming or sites that are built in conjunction with TV programming, requires a great deal of evaluation, some of it to make sure the goals are being met and some just to make sure the technical aspects are working. Only by honestly evaluating past productions can producers create even better programming.

Scriptwriting

An idea for a TV show can come from anywhere: a story in a newspaper, a dream, a casual conversation, research on the Internet, a brainstorming session with other writers. Getting from the idea to an actual production is a road full of potholes, and that journey begins with writing. Writers can be responsible for everything from a treatment or proposal to an actual script, using the appropriate script form or format for the production. Writers can also be involved in creating storyboards, if storyboards are used; even if an artist is hired for the drawings, a writer is responsible for the story.

Treatments and Proposals

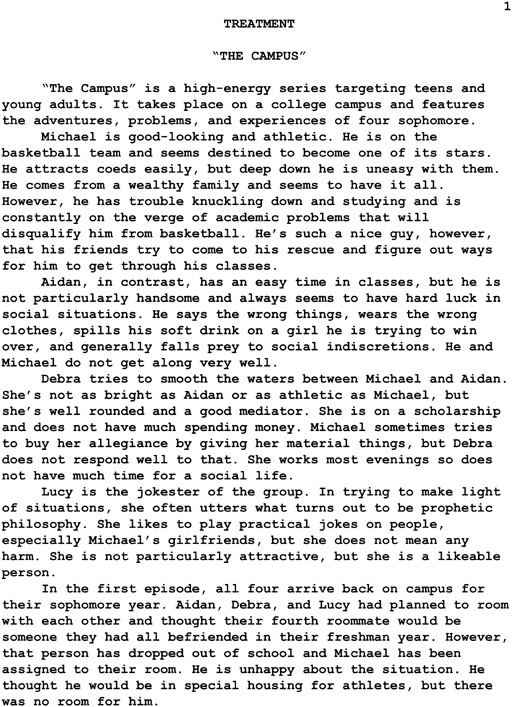

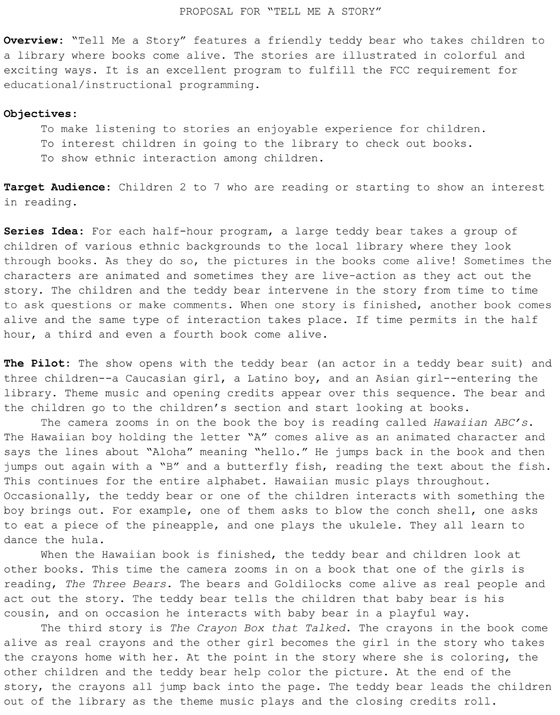

Most drama and comedy series start with a treatment. (See Figure 3.10.) This is a document of several pages, written in regular prose and in the simple present tense, that—to use a TV series as an example—tells the overall premise of the series, describes the main characters, outlines the basic plots for the first few episodes, and highlights the strong points of the idea. In some cases, a producer (or executive producer) with a track record of success from an outside production company makes an appointment with the appropriate network executives for a pitch meeting. A pitch can last from a few minutes to half an hour or more, during which the producer tries to convince the executives that they should buy the series idea. Often, they do this by comparing their idea to something that is already popular (e.g., Modern Family meets The Voice, in which dysfunctional, stressed-out families are singing contestants). The producer presents the information in the treatment orally and sometimes provides written material for the executives to study.

If the network executives like the idea, they might commission (i.e., pay for) one or more complete program scripts. If they like the scripts, they might order a pilot, a produced program that is usually, but not always, the first episode of the series. If they like the pilot and decide to schedule the series on a regular basis, they greenlight (give the go-ahead for) more scripts and productions. Throughout this process, the production company’s producer negotiates with the network regarding both creative and financial elements.

In other instances, ideas come from people at the network. In these cases a treatment is still needed, but the pitch meeting and pilot process are more informal. One-shot dramas, such as movies of the week (MOW, aka made-for-TV movies), often have a treatment as a starting point, but obviously the treatment outlines a single movie and not several TV episodes.

Many other types of programs that are not fiction-oriented also start with a written idea. Sometimes these are called treatments, but more often they are referred to as proposals. Magazine, talk, documentary, and game shows that are planned for syndication, cable or satellite TV, the Internet, or local broadcast often evolve from proposals. So do children’s programs and programs intended for educational or corporate outlets. Proposals define the purpose of the project, list the objectives, indicate the demographics (quantitative statistics such as age and gender) and psychographics (qualitative characteristics such as environmentalists or free spenders) of the target audience, give some details as to how the programs will be produced (e.g., animation, field production, studio), outline some of the planned segments, and provide information about the proposed budget and potential sponsors. (See Figure 3.11.)

A newscast proceeds very differently. If a network or station decides to present the news, no one needs to spell out specific ideas with a treatment or proposal: The ideas come from the news of the day. Parts of the newscast script are written during the course of a day (or several hours) as the producer and news director decide which stories are most important. Reporters and writers put together individual stories and transitions between stories that are to be read by newscasters. If a story seems to merit further investigation, a reporter or news producer might propose developing it as a special piece, though the proposal is likely to take the form of a verbal pitch rather than a written document, given the time constraints of news turnaround.

Script Forms

Because programs and circumstances differ, script forms also differ. The type of script needed for a drama would be overkill for a talk show. A music video that is highly postproduced can use a script with less structure than a news script that must give accurate, mistake-proof guidance for a live broadcast. An interactive multimedia game needs a different type of script than a non-interactive TV game show. Although many different script forms have evolved over the years, the main ones that you, as a student, are likely to encounter are two-column scripts, rundowns, outlines, film-style scripts, and storyboards.

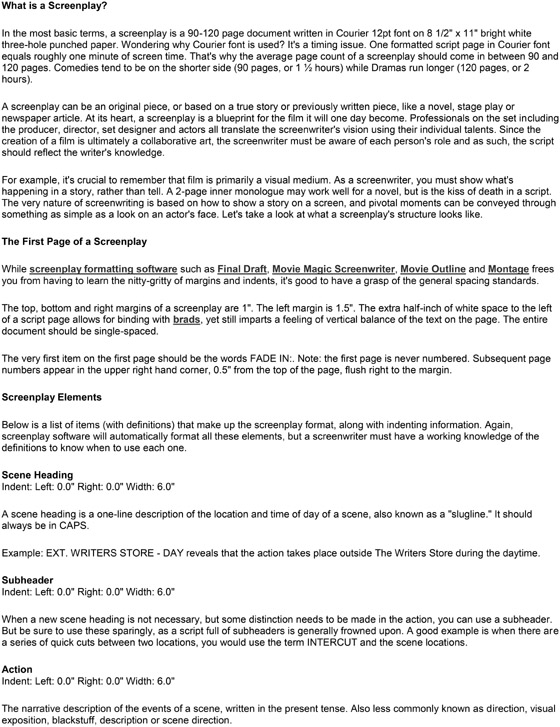

Two-Column Scripts

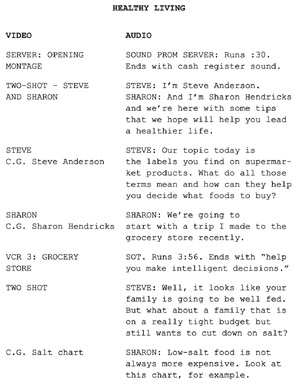

Two-column scripts are the ones most frequently used for multi-camera studio productions that are shown live or are live-recorded (“live-to-drive”). This script format, also called the split-page or the AV (audiovisual) format, is sometimes used for commercials and public service announcements (PSAs) because it lines up each visual element (live image, graphic, text) with its corresponding audio elements (dialogue, sound effects, music), making it easy for clients to visualize the production. The video descriptions are on the left-hand side, and the audio elements are on the right-hand side. (See Figure 3.12.) This layout makes it easy for the producer to gather all the materials needed. Additionally, the director can see what visual images should be on the screen as the talk progresses and can set up cameras for what will come next. Usually, the left-hand margin of a two-column script is wide enough to let the director jot down notes.

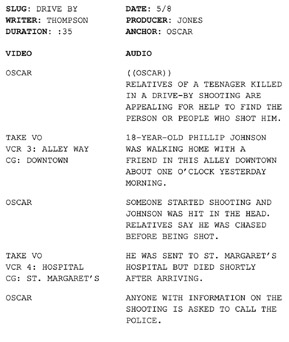

There are many variations on two-column scripts, depending on the type of program for which they are used. Some include every word of dialogue. Editorials and commercials, for example, need to be precise: No ad-libbing allowed. Other programs, such as magazine shows and newscasts, include all the words to be spoken by the anchors but only basic information about edited field reports that are to be rolled in (e.g., length, one-sentence summary, in-cue and out-cue), so that the director can bring them in and take them out without any flubs. Most newsrooms have a computerized form of a two-column script that all the writers use for their individual sections of the newscast. It contains such elements as the slug (story title), the date, the length, the writer’s name, and the newscast producer’s name. Usually, each segment of the newscast is on a separate piece of paper so stories can be juggled easily as news breaks—even during the newscast itself. (See Figure 3.13.) Still other programs, such as talk shows and game shows, indicate the general topics to be discussed or questions to be asked, but the answers cannot be scripted ahead of time (at least not normally).

Many scriptwriting software programs include a template for a two-column script, in addition to templates for other types of script. If you do not use a scriptwriting program, or the one you use does not include the AV format, you can easily create your own two-column script in Microsoft Word and some other basic writing programs. Create a header with the slug information: your name, program title, company or client or class number, date, and so on. Then select the “Table” function and set up two tables. In the left cell, type the video information: camera shot, subject, any special camera moves or effects, and the like. Tab over to the right cell, and type the audio information that corresponds to that shot: dialogue, music, sound effects, and the like. Then tab back to the left column to write the next visual shot, and over to the right column for the corresponding audio, and so on. If the default setting puts a border around the cells, and if you don’t want those borders, you can “select all” and then choose “no border” from the border menu.

Rundowns

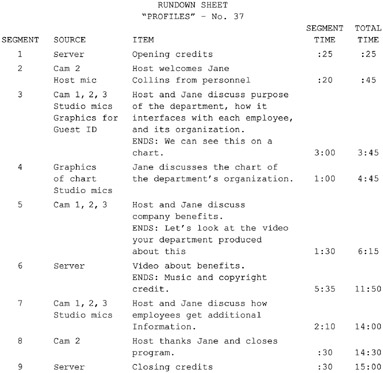

Rather than using a two-column script, some talk and game shows—and other programs for which little can be scripted ahead of time—use rundowns. (See Figure 3.14.) These list each segment to be included in the program, in sequence. Rundowns are often used for programs that are produced on a daily or weekly basis, such as Today and Meet the Press.

Specific information is given for each segment. This information may vary from one type of program to another, but generally it includes the source for that segment (computer or server roll-in, studio cameras, graphics, remote feed), a short description of what the segment contains, and how long the segment should run. If a program has a set length, such as one hour, the total running time might be indicated so that the director can tell if the overall program is running short or long. In-cues and out-cues—the opening and closing lines of dialogue, respectively—can help the director prepare for transitions.

Producers use the rundowns to make sure all the guests are confirmed and ready to appear in order. Usually, the same person directs these programs day after day, so he or she has a routine and is mainly concerned with anything unusual on a given day. A segment featuring statistics may require additional graphics to help viewers visualize the issue, or a piece with a live animal in the studio may require greater flexibility in timing.

News programs usually use both rundowns and two-column scripts. The rundowns indicate the order of the stories, and the scripts contain the actual words. The rundown is generally placed on screens near the anchors and most of the crew members. (See Figure 3.15.) The producer, stationed in the control room, changes the order of program elements as needed while the program is on the air, and those changes are reflected on each computer. The anchors, director, and others quickly rearrange their two-column scripts according to the producer’s changes.

Sometimes, rundowns include fully scripted material that can be written ahead of time. When they do, they look somewhat akin to a two-column script, in that they include a column for video and another for audio. The line between a detailed rundown and a nonspecific two-column list can be blurry, but how the script is categorized is not nearly as important as whether or not its format is useful for the talent, producer, and director.

Outlines

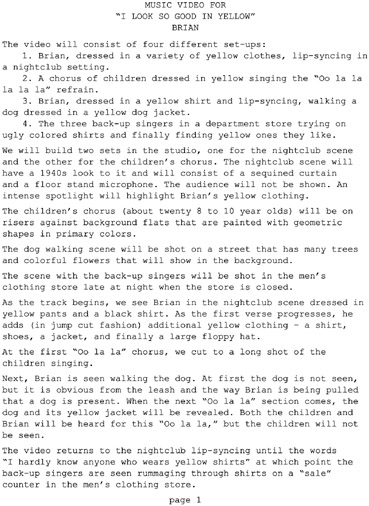

The line between rundowns and outlines can also be blurry. Outlines list the various elements of a program, usually in less detail than rundowns. They are often used for pieces such as music videos that are shot and then edited. (See Figure 3.16.)

Documentaries often lend themselves to outlines. The outline can indicate general items, issues, or circumstances to be investigated, but the real conclusions and findings cannot be planned until the material has been shot. Outlines must indicate to the producer the props, sets, locations, and other production elements that are needed to ensure a successful shoot. They need to give the director a general idea of what to shoot but allow plenty of room for improvisation.

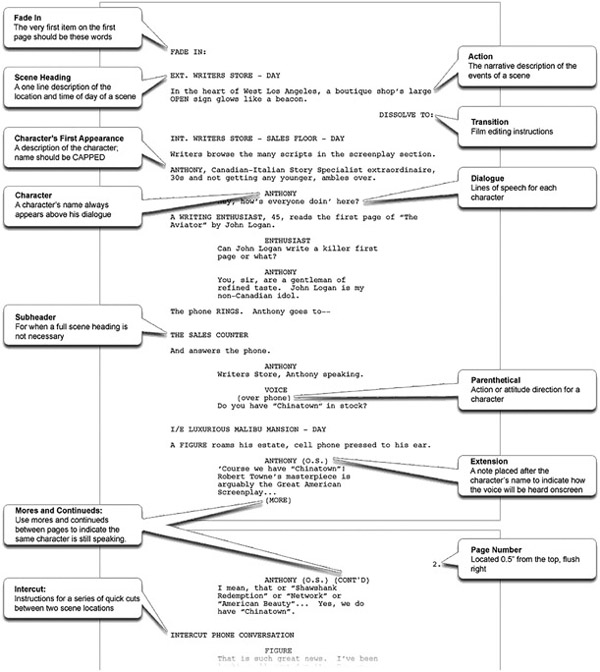

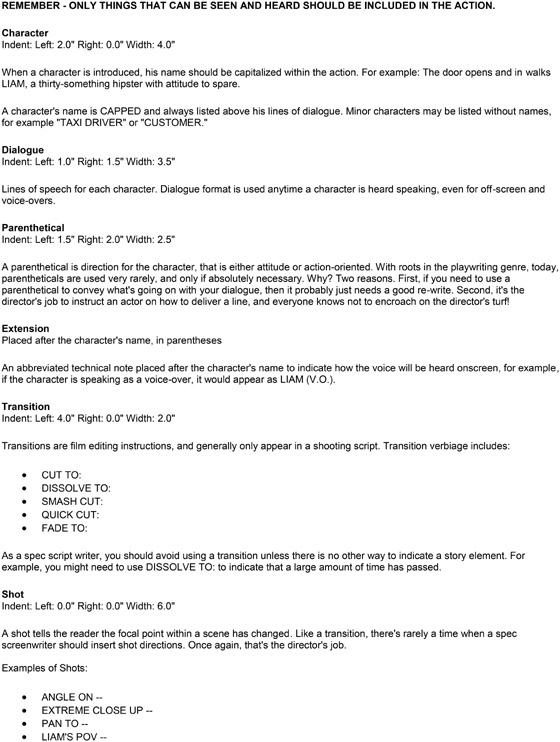

Film-Style Scripts

As might be evident from their name, film-style scripts use a format that has evolved over the last 100 years to produce theatrical movies. Figure 3.17a offers a sample film-style script page, and Figures 3.17b and 3.17c provide the basic screenplay format guidelines, all courtesy of The Writers Store. Within the movie business, film scripts are referred to as screenplays; in television they are often called teleplays. The generic term is simply script. The general form of the film-style script is used for TV programs that are shot single-camera style rather than multi-camera style, particularly hour-long dramas and movies of the week (MOWs), as well as single-camera comedies. One main characteristic of this script is that each scene is separated from the next so that each can be considered individually. Materials produced from film-style scripts are usually shot in a number of different locations, with all the scenes from one location being shot on the same day or succeeding days. This script style uses a “slug line” that highlights whether these locations are indoors (interior—INT.) or outdoors (exterior—EXT.), the location, and either DAY or NIGHT. These slugs can help a producer with preproduction planning. The producer also uses the descriptive paragraphs, or action lines, to determine what is needed in the way of props, set pieces, and so on. Additionally, the character names and corresponding dialogue are indented, keeping them separate from the writer’s descriptive material. This indentation gives the director and others room for notes and helps the actors pinpoint their lines.

Moreover, the director usually shoots each scene a number of times. Typically, the first time the camera films an overall shot of the scene, say a two-shot of a man and woman arguing. This master shot records the full scene (actors’ blocking, gestures, etc.) and is used for reference in editing as well as serving as one potential shot in the final cut. After the master shot, other angles are recorded, such as over-the-shoulder shots, medium shots, and close-ups. These are called setups because the camera has to be set up again from a different perspective each time, and the lights, mics, background elements, and so on might also need to be set up differently or at least adjusted slightly for optimal framing, composition, and sound. All of these other angles make up the coverage for that scene: the totality of shot perspectives available for the editor to assemble the final scene. In our example of the man and woman arguing, the second time the scene is shot, the camera records a close-up of the woman delivering her lines and reacting to the man’s lines. The third time, the close-up is of the man.

The film-style script, by showing each distinct scene, helps everyone involved figure out what to shoot under the guidance of the director who has the final say. Film-style scripts are very thorough. They include all the dialogue spoken by the actors, describe all the action that takes place, and indicate moods and emotions. Of course, the director and actors have creative freedom to alter the words. The final interpretation and execution of actions, dialogue, and emotion are the province of the director (hence, the occasional conflict about creative control).

For complete details on the format of the film-style script, consult the Writers Guild of America or any of a number of excellent screenwriting books that cover this topic.3 Also, there are a variety of scriptwriting software programs that format scripts in the film style, as well as other script styles. The most-used program among professional screenwriters is Final Draft, and there are others, such as Scriptware and Movie Magic Screenwriter. Some free programs can also be downloaded, such as Celtx and others. Additionally, some writers set up their own screenplay template in Microsoft Word or other writing programs. The online Writers Store is a good resource to learn about the screenplay format and writing programs. Perhaps your university or organization has purchased a license for a scriptwriting software program you can use.

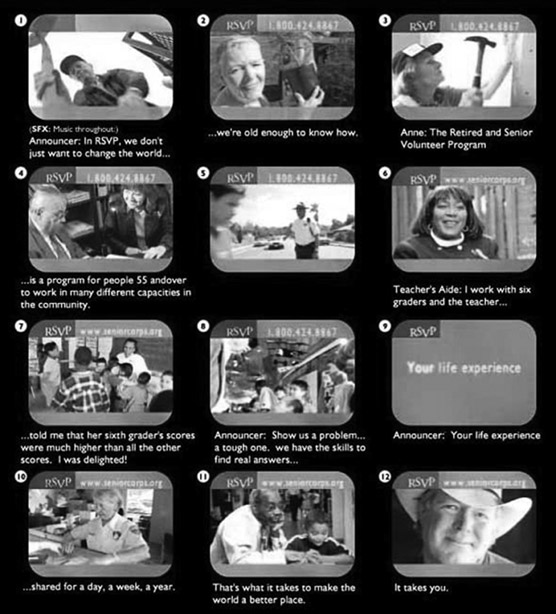

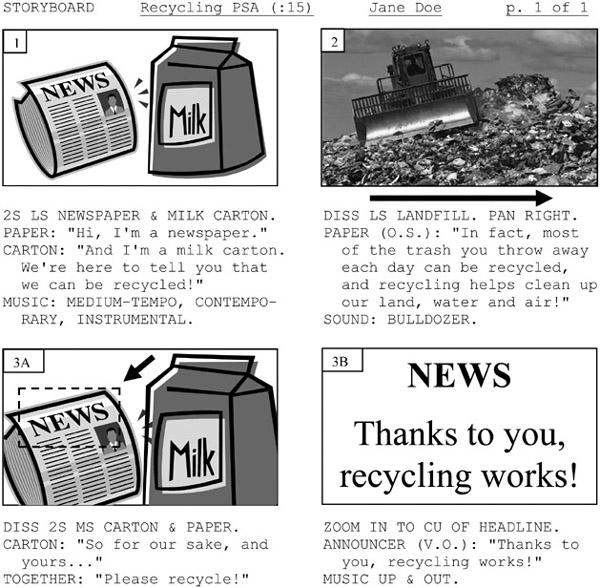

Storyboards

Storyboards show pictures of a production’s visual elements and often describe the shots, actions, and any visual effects, as well as indicate any dialogue, music, and sound effects. Storyboards vary from one production to another and from one artist to another. They all incorporate sketches of each shot, though, or at least each principal shot. In addition to the sketches, sometimes called panels, written descriptions might include the script itself (Figure 3.18) or some or all of the following (Figure 3.19):

Video Description

- Shot size (e.g., long shot, medium shot, close-up)

- Subject (e.g., man, woman, Ted, Alice)

- Action (e.g., Jane walks screen left, car screeches around corner)

- Camera moves or special effects (e.g., pan right, zoom in, camera flashes, smoke rises)

Audio Description

- Dialogue (in- and out-cues are okay for lengthy lines)

- Sound effects (e.g., gunshot, alarm clock)

- Music (e.g., contemporary rock, classical, country, jazz up-tempo, slow tempo)

Additional Storyboard Conventions

- Drawings should be in the correct aspect ratio for the production (e.g., 16:9 for HDTV).

- Drawings should follow the conventions of framing and composition (e.g., long shot = head-to-toe; medium shot = waist-up; close-up = shoulders-up; two-shot; rule of thirds; look space; head room; see Chapter 4).

- A straight cut between shots is the assumed transition; there is no need to write “cut to” between sketches; only indicate other transitions (e.g., dissolve, fade, wipe, key).

- For subject movement within the frame (e.g., person walking, car driving), indicate the direction of the movement with a dashed line inside the frame.

- For camera movement, indicate the direction with a solid line outside the frame (e.g., an arrow below the frame pointing left indicates a pan or truck left; an arrow to the right of the frame pointing up indicates a tilt or pedestal up).

- For a zoom or dolly in or out, draw the widest shot and then within that shot draw a smaller frame with dashed lines around the part of the image that is the tighter shot; a solid arrow indicates the direction (in or out).

- For pans, trucks, tilts, and pedestal (crane) shots that start on one image and end on another, draw two panels—one for the start and another for the end—and label them with the same shot number, followed by “A” and “B” (e.g., 3A, 3B).

Storyboards are usually used for short productions such as commercials or music videos. Most animated films are also “previsualized” in storyboards. A live-action drama can certainly be storyboarded, but that involves a great deal of artwork and pages and pages of paper. Sometimes, directors storyboard complicated scenes to visualize them better. Some noted directors, including Alfred Hitchcock and Steven Spielberg, are known for extensive storyboarding as part of their preproduction. Producers should examine storyboards closely to make sure all the props and other production elements are ready.

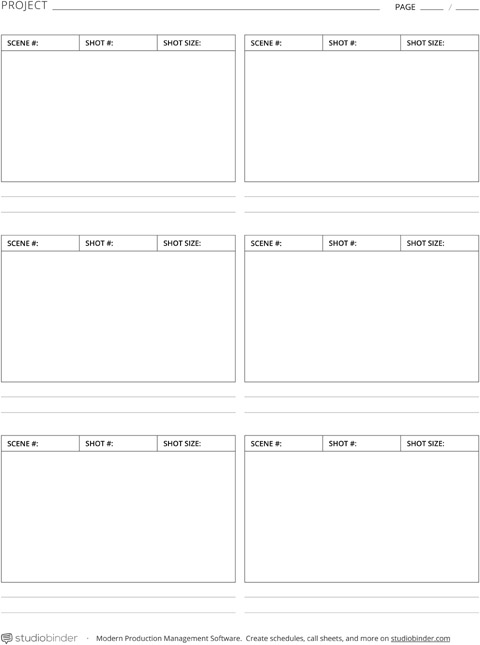

Clear visualization is more important than great art in storyboarding; after all, a storyboard is a planning tool and not a final production (though professionally drawn storyboard sketches are sometimes sequenced into animated videos). For your storyboards, you can sketch simple stick figures, or use an easy drawing program (e.g., insert shapes in Microsoft Word), or search clip art files and download images that are close to what you visualize. On the Video Production website, a blank storyboard sheet is provided to copy and use. Additionally, many sample storyboards and storyboarding software can be found online. Usually, these programs contain a large selection of ready-to-go artwork: people and objects that can be placed in a frame and manipulated—turned, made larger, made smaller, and so forth. These programs also let you sketch your own storyboard panels. There are many storyboard software programs, with names like FrameForge, Storyboard That, StoryBoard Quick (Power Production), and StoryBoard Pro (Atomic Learning). You can also download free storyboard templates from StudioBinder. One sample blank storyboard is included in Figure 3.20, which you may copy and use.

The type of script you choose to use—two-column, rundown, outline, film-style, or storyboard—depends on the type of program you are undertaking and the type of material with which you feel most comfortable. Scripts and storyboards are primarily blueprints for production. People who try to produce without a script are asking for trouble, in the same way as a builder attempting to construct a house without a basic blueprint.

Focus Points

After reading this chapter, you should know . . .

- About the different types of producers (executive, line, associate, assistant) and how their jobs differ.

- Why producers sometimes opt to be hyphenates and what their duties involve under those circumstances.

- How to build a budget and adhere to it.

- The process of casting and selecting a crew.

- Methods for preparing schedules for different types of shoots.

- How to deal with legal issues such as copyright.

- The types of records producers need to keep digitally and as hard copies.

- Why it is important to promote and evaluate programs.

- How to construct and utilize a treatment and / or proposal.

- About the different forms of scripts (two-column, rundown, outline, film-style, storyboard) and how and when to use each.

Review

- How do the duties of executive producers, line producers, and associate producers differ? Which one would you prefer to be, if any?

- What differences would you encounter between budgeting an action-oriented movie-of-the-week for a network and budgeting a company president’s “state of the company” talk for an in-house corporate video? What would be some differences in terms of casting and selecting the crew? In terms of devising a production schedule?

- Come up with an idea for a sitcom series and discuss the major points you would include in a treatment. What type of script do you think you would eventually use?

- Come up with an idea for a video that highlights some program or event at your university. What points would you include in the proposal? What type of script would you eventually use?

On Set

- Acquire several script forms—such as a two-column script, a rundown, and a storyboard—from a local television facility or from a site such as simplyscripts.com. Analyze them, and explain why the form of script is appropriate for the particular production and how the director might use each script. If possible, also acquire the budgets for the productions.

- Using the rate sheets provided in Figures 3.2a and 3.2b and the budget sheet in Figure 3.4, create a budget for a hypothetical production.

- Using the blank FACS form in Figure 3.7, fill out a form for a hypothetical production. If possible, obtain some FACS sheets from other production facilities and compare them to the one used in your facility.

Notes

1The job of the UPM and its title have evolved. Historically, a unit manager worked for a production facility, and a production manager worked for an independent production company. On the one hand, a unit manager worked for a network or station that produced some of its own shows and rented out its facilities to others (corporations, advertisers, or production companies). The unit manager was in charge of drawing up and adhering to the rate card and scheduling the facilities for use by both in-house producers and outside clients. On the other hand, production managers were usually associated with a particular project rather than a particular facility. They determined what costs would be incurred by the project: people, facilities, supplies, and other requirements. But this line has blurred over time. For many projects, the two titles have been combined, and the person dealing with schedules and budgets is called the unit production manager.

2Your university most likely has a similar form that you should use. If not, your university’s attorneys should be consulted before you use this form.

3This book does not pretend to be a text in scriptwriting. What is given here is merely an overview of script forms. For more information on scriptwriting, see such books as the seminal Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, rev. ed., by Syd Field (Delta, Crystal Lake, IL, 2005); Edward J. Fink, Dramatic Story Structure: A Primer for Screenwriters (Routledge / Taylor & Francis, New York, 2014); Marie Drennan, Vlad Baranovsky, and Yuri Baranovsky, Scriptwriting 2.0: Writing for the Digital Age (Routledge / Taylor & Francis, New York, 2012); Jule Selbo, Screenplay: Building Story through Character (Routledge / Taylor & Francis, New York, 2016); Frank Barnas and Ted White, Broadcast News Writing, Reporting, and Producing, 6th ed. (Focal Press, Waltham, MA, 2013); Claudia H. Johnson, Crafting Short Screenplays That Connect, 4th ed. (Focal Press, Waltham, MA, 2014); Alex Epstein, Crafty TV Writing: Thinking Inside the Box (Henry Holt, New York, 2006); Robert L. Hilliard, Writing for Television, Radio, and New Media, 11th ed. (Cengage Learning, Boston, 2014); and Milan D. Meeske, Copywriting for the Electronic Media, 6th ed. (Wadsworth / Cengage, Boston, 2008).