Owing to the proliferation of broadcast, cable, and Web outlets, and an emerging global media cloud supporting 2D and 3D content, the demand for skilled craftspeople has never been greater, with resourceful shooters regularly pursuing an array of interesting and worthwhile projects. Of course, given today’s fragmented marketplace, the shooter must learn to do a lot with relatively little—and that’s the focus of this chapter.

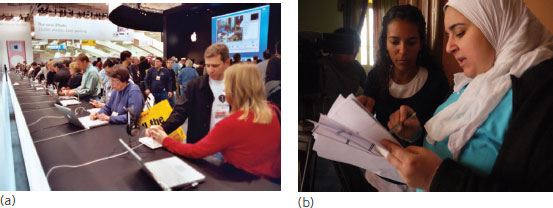

FIGURE 3.1

Along every path and byway, the world is rife with compelling stories waiting to be told.

In today’s media environment, achieving a professional look can be a challenge, for all the scrimping and cutting of corners in budget and schedules, viewers still demand a high level of craft whether watching American Idol, The Situation Room with Wolf Blitzer, or a high school play. No doubt as a shooter, you want to meet your audience’s expectations despite the monetary or time limitations imposed upon you.

Craft—not which manufacturer’s camera you use, what flavor of flash media you prefer, or whose recording format you ultimately employ—will always be the principal factor in your success. Craft is the most intangible of all commodities, the elusive quality that places you head and tripod above the next guy who just happens to have the same mass-produced camera with all the bells and whistles and useless digital effects.

FIGURE 3.2

The antithesis of small-format video. American photographer and filmmaker Willard Van Dyke prepares to shoot with an 8 × 10 view camera in 1979. To the great shooters of the past, every shot had to count. Composition, lighting, and point of view all had to work and work well in service to the story. Once upon a time, the economics of the medium demanded clear uncluttered storytelling.

Go ahead. What do you see? In the 1970s, in lieu of a social life, I strolled the Dartmouth College campus flaunting a yellow index card with a rectangle cut out of it. Holding the card to my eye, I’d frame the world: Oh, there’s a maple tree; there’s an overflowing dumpster; there’s my friends streaking naked through the dining hall. It sounds silly in retrospect, but this simple exercise forced me to think about what makes a visually compelling story, and oddly it has little to do with the subject itself.

Indeed I discovered that almost any subject could be engaging given the proper framing and point of view. Paradoxically what mattered most was not what I included inside the frame but what I left out. To a young shooter developing awareness in the art of seeing and framing the world, this was a major revelation!

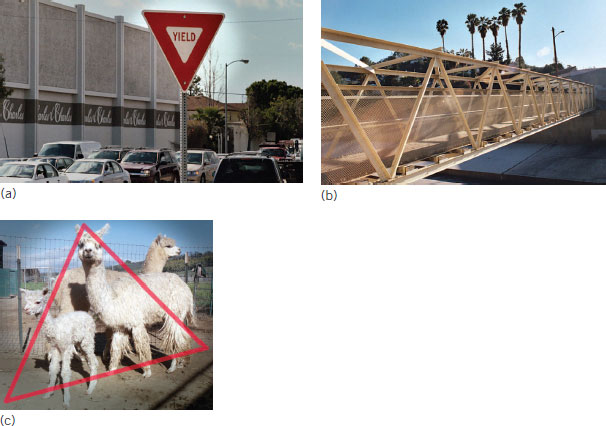

FIGURE 3.3

Put a frame around the world. What do you see? The world is a chaotic place.

FIGURE 3.4

These old masters from Hoboken, New Jersey, rigorously control the frame boundary, excluding everything not helpful to the visual story.

FIGURE 3.5

You can help contain the world’s chaos by placing a frame inside the frame by shooting through a doorway or window.

If you like my card idea, you can go further by placing a second card behind the first. Holding the cutout cards to your eye and altering the distance between them simulates the variable field of view of a zoom lens. Expensive gear manufacturers might not appreciate this (almost) no-cost gimmick, but it can be invaluable to the new shooter developing his eye and visual storytelling skills.

This is your mantra! Your raison d’être! It’s what guides and empowers you as a shooter and storyteller. You understand that every object, every frame element is included for a reason. Every light, prop, and shadow has a function. Every movement of the camera or change in field of view is deliberate and supports the story in a clear and identifiable way.

As we go about our daily lives, we don’t notice the irrelevant details in the story around us; the processor 1 in our brains being adept at framing the world and effectively isolating only what is relevant. In our minds, we frame an establishing scene when we enter a new location. We walk into a coffee shop and our eye is drawn to a friend at a table, and as we move closer, our focus narrows on the story details in her face—maybe a tear, a runny nose, or a bloody lip. We see these details and try to decipher their meaning, and ignore the nonpertinent elements behind, around, and in front of her. Our brains work to reframe the world, creating a virtual movie in our mind, composing, cropping, and placing into sharp focus only those elements deemed essential to the “story.”

For some folks, the brain’s ability to exclude is subject to overload. Feel blessed you’re not the great comic book artist Robert Crumb, who was reportedly so tormented by the visual clutter around him that it eventually drove him mad. Indeed, most of us living in large cities are only able to do so because we’ve learned to exclude the aural and visual noise that constantly bombard us. Just as we don’t notice over time the roar of a nearby freeway, so too do we come to ignore the morass of ugly utility lines crisscrossing the urban sky. The camera however placed in front of our eye interrupts the brain’s natural filtering process; the latest cameras from Sony, Panasonic, or JVC, having no ability (yet) to exclude, exclude, exclude!

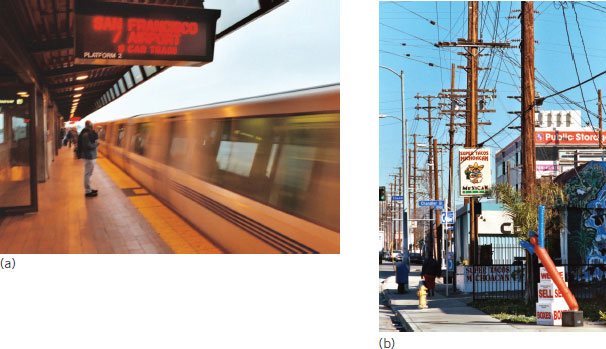

FIGURE 3.6

The movie in our mind. Without giving it a thought, the eye frames the scene at right, excluding what is not relevant to the story. Your nifty new camcorder or DSLR has no such capability.

FIGURE 3.7

Visual noise can be just as oppressive as aural noise. In framing a scene, the shooter must consciously exclude the clutter that undermines clear visual storytelling.

Just as in any intimate relationship, it’s a good idea to consider your loved one’s needs. What do viewers really want when entering a theater and seeing your images flicker across the screen? Above all, they want to be shown the world in a way they haven’t seen before, and they are willing to work hard, even suffer, to make it happen.

FIGURE 3.8

Show me a world I haven’t seen before! This is your goal, your mission, and your main responsibility as a shooter!

FIGURE 3.9

“Curves Ahead” (Photo of Gypsy Rose Lee by Ralph Steiner).

I recall interviewing the great curmudgeon photographer Ralph Steiner at his Vermont home in 1973. Ralph was one of the 20th century’s most gifted storytellers, and his photographs, like his manner of speaking, were anything but boring. One afternoon he clued me in to his secret:

If you’re going to just photograph a tree and do nothing more than walk outside, raise the camera to your eye, and press the shutter, what’s the point of photographing the tree? You’d be better off just telling me to go out and look at the tree!

“Constantly searching for a unique perspective is not easy. It’s painful!” Ralph bellowed, his voice shaking with passion. “You have to suffer! Running around with a camera can be fun once in a while, but mostly it’s just a lot of suffering!”

This suffering notion is worth exploring because I truly believe the viewer wants to share our suffering. It’s a noble reassuring thought. It also happens to be true.

FIGURE 3.10

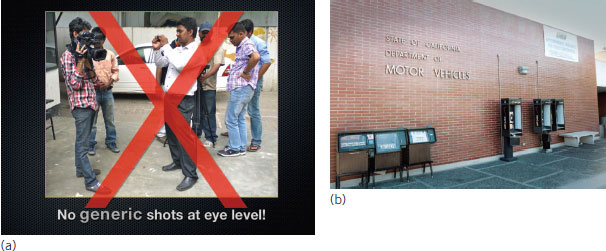

Interesting angles are an adventure in seeing. They challenge the viewer and increase the perceived value of your story.

FIGURE 3.11

No medium shots at eye level! Not now! Not ever! Such shots are boring. It’s what we see every day when we stroll past the 7-Eleven or DMV office.

FIGURE 3.12

Hey! What’s in focus here? What am I supposed to look at? Make your audience work. Make ‘em suffer and they will appreciate you more for it.

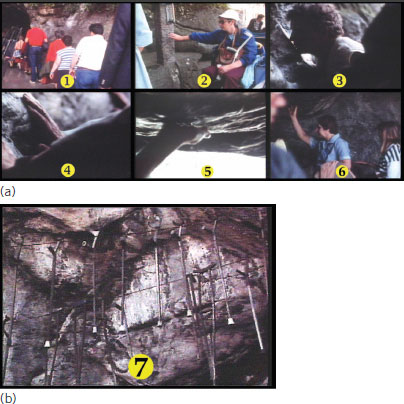

FIGURE 3.13a

Shoot far.

FIGURE 3.13b

Shoot close.

FIGURE 3.13c

Shoot high.

FIGURE 3.13d

Shoot low.

FIGURE 3.13e

Shoot up.

FIGURE 3.13f

Shoot down.

FIGURE 3.14

(a) The wide angle lends grandeur to a scene and communicates expanse and scope. (b) This close-up says, “Look at this! This man is important!” (c) Sometimes a close-up may inflict actual pain in an audience, as in the slitting of the eyeball from Salvador Dali’s Chien Andalou (1929). Most viewers do not appreciate this much suffering!

We gain this primarily through close-ups and by (a) placing less important objects out of focus, (b) cropping distracting elements out of frame, (c) attenuating the light falling on an object, or (d) de-emphasizing the offending object compositionally.

FIGURE 3.15

Go close. Get personal. Get in the face of your subject and bear her wrath!

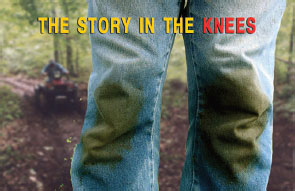

FIGURE 3.16

A shooter searching for a unique perspective will inevitably soil the pant knees. Make sure yours are plenty dirty at the end of the day!

FIGURE 3.17

Selective focus helps isolate elements inside the frame and assigns them a relative value to the story.

FIGURE 3.18

Prudent cropping excludes what isn’t helpful to the visual story.

FIGURE 3.19

The adept use of color and contrast helps direct the viewer’s eye inside the frame.

FIGURE 3.20

Strong compositions de-emphasize the less essential elements. Here, my son’s pointing finger gains weight in the frame while his mom (partially obscured) is compositionally reduced in importance.

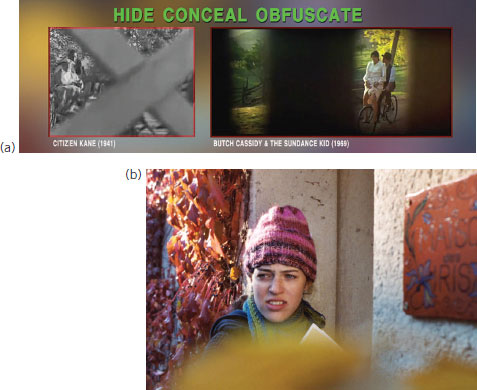

The principle of exclusion must be applied with skill and good taste. If you look at great cinematographers’ work, you’ll notice that many like to shoot through and around foreground objects. This helps direct the viewer’s eye inside the frame and strengthen the (usually) desirable 3D illusion.

But what are we really doing by obscuring or completely concealing our subject at times, then revealing it, then hiding it again? We’re making the viewer suffer. We’re skillfully, deliciously, teasing the viewer, defying him to figure out what the heck we’re up to. Yes, point your viewer in the right direction. Give him or her a clue or two. But make it a point to obscure what you have in mind. Smoke, shadow, and clever placement of foreground objects can all work. The key is not to make the visual story too easy to decipher. Make your viewers wonder what you’re up to, make them squint, squirm, and suffer—and they’ll love you and your story for it.

FIGURE 3.21

“What comes lightly is valued lightly,” noted America’s first postmaster, inventor, and adorner of the $100 bill. No doubt Ben Franklin would’ve made a great video shooter. Now if I can just see around those damn cumulus clouds!

FIGURE 3.22 a,b

The strategic placement of foreground objects imparts mystery in a scene and increases the audience’s desire to see around the obstruction. When your audience must make this effort, it is more likely to appreciate the story and your images.

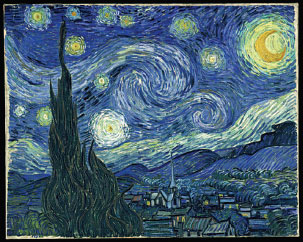

FIGURE 3.23

The 19th-century Impressionists didn’t make it easy for viewers and neither should you! Viewing a Van Gogh is an adventure! Your images and compositions should be just as challenging.

A shooter’s primary responsibility is to represent the 3D world in a 2D medium. Communicating a third dimension is usually desirable because it helps to promote the illusion of real life, that is, real players operating at a real time in a real place.

For the artist, there are two principal ways to foster the illusion of a third dimension: through skillful use of perspective and texture. Usually we want to maximize both.

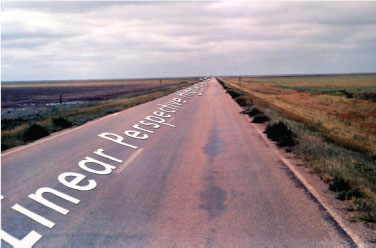

The lonely highway converging on the horizon is a classic example of linear perspective. Linear perspective offers a powerful monoscopic2 depth cue, conveying a strong 3D sense without resorting to stereographic depth cues that would require special glasses and complex stereo capture (see Chapter 7). Linear perspective often has a strong storytelling component as well, helping to guide the viewer’s attention appropriately inside the frame.

Aerial perspective is gained from looking through multiple layers of atmosphere over expansive landscapes. Owing to the usual high contrast and fine detail in such scenes, aerial perspective is seldom used effectively by shooters with lower-end cameras and equipment.

Besides linear and aerial perspectives, the shooter usually strives to maximize the texture apparent in scenes. This can be achieved through lighting by producing a raking effect as in Figure 3.26, or by exploiting the natural quality and direction of the sun as in Figure 3.27.

FIGURE 3.24

Linear Perspective Highway, Kansas. In most cases, the shooter seeks to maximize the 3D illusion. This scene, photographed by the author while bicycling across the United States in 1971, conveys the story of a journey and highway that seem to have no end.

FIGURE 3.25

Aerial perspective seen through increasing layers of atmosphere is common in classical art and photography but is seldom used to advantage in small-format video.

FIGURE 3.26

The texture and shadow in this boy’s face suggests that he is real, that he exists. A story in which he appears will also therefore seem more real.

FIGURE 3.27

The shadows in this backlit scene strongly suggest a three-dimensional world.

FIGURE 3.28

Reduced texture in the skin is usually desirable when shooting close-ups of your favorite starlet. It can be best achieved via soft frontal lighting, application of a diffusion filter, or enabling the reduced skin detail feature in the camera.

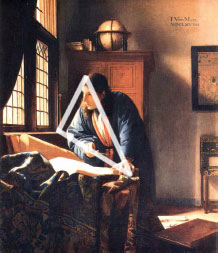

Composition plays a vital role in communicating the desired visual message. Consider the most memorable shots from movies, the great pyramids of Giza, and box-girder bridges, and it is easy to see how the triangle can be the source of great strength, lying at the heart of our most engaging and seductive creations.

FIGURE 3.29

The triangle as a source of compositional strength was widely exploited by the Old Masters, as in The Geographer (1668) by Vermeer.

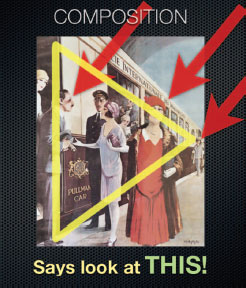

FIGURE 3.30

The key points of interest in this travel poster form a triangular pattern.

The essence of developing a shooter’s eye is learning to see the triangles around us. These triangles serve our storytelling needs by appropriately directing the viewer’s eye inside the frame. In tiny-sensor cameras with great depth of field,3 the relative inability to focus in clearly defined planes means we must rely more on composition and less on selective focus to highlight key picture elements. The video shooter, like a builder of steel-girder bridges, can derive great strength and storytelling prowess from compositions built on the power of the triangle.

FIGURE 3.31

Like steel girder bridges, strong compositions rely on the power of a triangle for strength. Whether realized or not, seeing the world as a series of triangles is a core capability of every competent shooter.

FIGURE 3.32

Is this the beginning of a beautiful friendship? The ensemble cast obligingly forms a triangle in the climactic scene from Casablanca (1942).4

For centuries, the strength of the triangle has been recognized by artists and engineers. The Rule of Thirds divides the frame into roughly three horizontal and vertical sections, the artist typically placing the center of interest at one of the intersecting panes. A composition built on the Rule of Thirds is the de facto approach for many shooters. Keep in mind this “rule” is in fact only a tool, a starting point for further exploration.

FIGURE 3.33

The Great Masters seldom placed the center of interest in the middle of their canvases. As an artist you can apply the Rule of Thirds to achieve powerful compositions. This is Turner’s Dutch Boats in a Gale painted in 1801.

FIGURE 3.34a

The columns of the Pantheon dwarf the figures at the lower third of frame. Television’s horizontal perspective generally precludes such compositions, although this may change with the streaming of content to vertically held mobile devices.

FIGURE 3.34b

The eye is drawn naturally to the laundry lines and couple trisecting this Venice alley.

FIGURE 3.34c

This trio of Bangladeshi women stakes out favorable positions inside the frame.

FIGURE 3.34d

Three pelicans in a triangle are observing the Rule of Thirds. Thanks pelicans.

Centuries ago, the School of Athens recognized the power of the widescreen canvas to woo audiences. Today shooters have much the same capability, capturing images in the 16:9 format. Most camcorders today no longer shoot 4:3 in any flavor, shape, or form!

FIGURE 3.35

Raphael’s School of Athens. The Golden Rectangle, aka 16:9, captivated the art patrons of the Renaissance. Audiences today remain no less drawn to the format.

FIGURE 3.36

The Golden Rectangle can be highly seductive! There’s a reason credit card companies choose 16:9!

As filmmakers and storytellers, we usually want to connect with our audience and form an intimate bond. But suppose our story requires just the opposite. Tilting the camera at a Dutch angle connotes emotional instability or disorientation. Cropping someone’s head off makes that person seem less human. Running the frame line through a subject’s knees or elbows is painful and induces the same pain in the viewer. Maybe this is what you want. Maybe it isn’t.

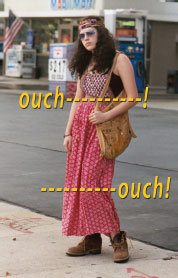

FIGURE 3.37

Ouch! Cropping through sensitive areas of the body can evoke pain in your viewer. You dig?

FIGURE 3.38

When shooting a close-up, the upper one third of frame normally passes through the subject’s eyes. Most viewers accept this composition as correct.

FIGURE 3.39

Where is the president traveling today? Respecting cinematic conventions can greatly improve the efficiency of your visual storytelling. Here Air Force One is flying eastward from Los Angeles to New York.

FIGURE 3.40a

A good story has no rules! These “poorly” composed scenes for National Geographic recreated the rocking and rolling earthquake that devastated Mexico City in 1985.

FIGURE 3.40b

A wrecked building after the 1985 earthquake. The Dutch angle helps tell the story.

Every location has a unique visual character. When I scout a location, I ask myself, “Is this place consistent with the story I wish to tell?” Is it a 3D or a 2D kind of place? Is it a wide-angle place or a telephoto place? Recognizing the character of a location and how it may or may not support the desired visual story is critical to my success as an effective shooter.

FIGURE 3.41a

Zanzibar is a 3D place. The low sun reveals exquisite texture.

FIGURE 3.41b

Sydney is a bright, pleasant day place.

FIGURE 3.41c

Provence is a 2D place, flat like a painting populated by color swatches.

FIGURE 3.41d

New York is a vertical telephoto place.

FIGURE 3.41e

Prague is a rainy/snowy night place.

FIGURE 3.41f

Los Angeles is a horizontal wide-angle place.

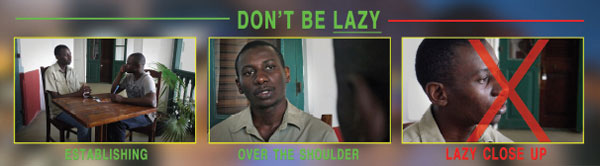

Effective storytelling with a camera requires that you have a point of view and that you assert it. The asserted point of view may be one you’re paid to represent, but it is your point of view nonetheless—and it is your story, at least visually. So press on. Express your view of the world. Express it with gusto. Make Jean-Paul Sartre proud!

A clear point of view demands precise camera placement, eyeline, and lens choice. After more than 100 years, the conventions of cinema are well established, and today’s video shooter would be wise to understand them. Fundamentally, the shooter’s craft can be reduced to only three shots:

1. We see the protagonist.

2. We see what the protagonist sees.

3. We see the protagonist react.

That’s it. This triptych is then repeated over and over until our documentary, feature film, or corporate program concludes, maybe hours later.

Some filmmakers like the famed French director Jean-Luc Godard may pursue various detours along the way, but most cinema (especially American cinema) is constructed on this simple premise. Indeed, one reason why Hollywood stars command such huge fees is because audiences are conditioned to experience the film story though their point of view. This intimacy with the mass audience has the effect of contributing hugely to the market value of a relatively few stars.

The expression of a clear point of view is the hallmark of a great director. In Citizen Kane,5 25-year-old Orson Welles masterfully used point of view to propel the story. At a political rally, when the scene opens the camera drifts in slowly and assumes a very low angle of Kane the candidate in front of a towering campaign poster of himself. It is soon revealed that the low perspective belongs to Kane’s son who (literally) looks up to his dad. As the scene progresses, however, the point of view shifts subtly until we are looking down on the candidate; the stature of the candidate is demeaned and reduced by the overhead perspective. This turns out to be the point of view of Kane’s political rival, who then goes on to expose the extramarital affair that will ruin the man and sink his candidacy.

FIGURE 3.42

The cinema distilled to its essence: (a) the protagonist, (b) what the protagonist sees, and (c) the protagonist’s reaction. Entering the protagonist’s point of view quickly helps build intimacy with the viewer. Stories and characters in which the viewer feels a strong connection need not be technically flawless.

FIGURE 3.43

From his son’s point of view, Kane appears larger than life, but as the scene evolves the point of view shifts to the condescending down angle of Kane’s political nemesis. The change in point of view propels the scene and story forward. For the shooter point of view determines where to place the camera!

Given the bulk of assignments today with tiny budgets, shooters must necessarily adopt a more disciplined approach, and because digital video’s perceived low cost tends to work against such discipline, the successful shooter must impose the discipline on himself—a challenge to many of us for the same reason that we tend not to eat right, get enough sleep, or go to the gym.

In the days of film cameras and pricey film stocks, the penalty for inefficiency and lack of skills was severe, so the posers lurking among us were quickly weeded out and returned to their day jobs. Today such weeding out seldom occurs or at least in quite the same way. Hoping to capture something, anything, of use the undisciplined shooter simply churns away, memory card after memory card, until fatigue or boredom sets in, which mercifully finally compels him to stop.

And does it matter if these posers are not getting anything interesting or useful? They keep rolling and rolling. Hard drive space is cheap, they’ll tell you, as if that’s the issue. OMG!

A better approach is having a clear shooting strategy in the first place. When shooting documentaries, I watch for moments of crossing action, objects entering and leaving the frame, and verbal cues and moments of dialogue that will make for a more easily editable show. It’s really a matter of knowing what you want, which also implies knowing what you don’t want and therefore don’t have to shoot.

In the days when the recording medium (film) was expensive, shooters might barely shoot two 35mm magazines for a 30-second commercial. This happened to me on a health club spot in 1980. If I had shot more than 8 minutes of film, I’d have risked being seen as wasteful or incompetent. Now on some assignments, if I don’t shoot 500GB by the end of the day, I am accused of dogging it. “What am I paying you for?” I heard one producer complain to me on a recent cable shoot.

C’mon. What are we talking? Sure, bits of data stored in whatever form are relatively cheap. But that’s not the whole story. Consider the poor devil (maybe you!) who has to review, log, and capture, the endless hours of rubbish. Regardless of how cheap it may have seemed to roll the camera without any plan or forethought, the shoot-everything-in-sight approach is hardly a wise system. Not by a long shot. Better that the cameraperson edit as he or she rolls and watch and listen for the cut points that will make the show later.

Today, despite the advances in technology, there is still a severe penalty for a shooter’s lack of discipline. Burning through a truckload of memory cards will not save you if you’re not providing what the story and the editor needs. In most cases, this means providing adequate coverage, that is, the range of shots required to tell a compelling story.

In 1987, I was on assignment in Lourdes, one of the most visited tourist destinations in the world. Every year millions of devout Catholics flock to the grotto in the south of France where the young Bernadette was said to have interacted with the Virgin Mary in 1858. To the faithful legions, the water in the grotto offers the promise of a miracle, and indeed, many pilgrims in various states of failing health come seeking exactly that.

From a shooter’s perspective, the intensity etched into each pilgrim’s face tells the story, and if there were ever a reason for close-ups this would be it. I knew I needed at most two wide shots, the first to establish the grotto and streams of pilgrims and the second to reveal the crutches abandoned at the grotto exit, presumably by those who’ve been miraculously cured.

In practical terms, I work my subjects from the outside in, meaning I do my establishing shots first and then move in, exploring interesting angles along the way. Thus, the viewer shares in my exploration, as I uncover compelling details in tighter and tighter close-ups.

For an audience, this exploration can be exhilarating. In the grotto, I moved in steadily in back-and-forth angles, the camera riding atop my Sachtler tripod, an indispensable tool for capturing riveting close-ups. Here the close-ups were particularly emotional: the pilgrims’ hands rubbing across the well-worn rock, a woman in semi-silhouette kissing the grotto wall, the believers’ hands shakily clutching a crucifix or rosary.

FIGURE 3.44

This grotto scene from a 1987 Lourdes documentary illustrates good coverage. In the opening shot I establish the grotto. I reverse and work closer in shot 2. Close-up shots 3, 4, and 5 do most of the storytelling in the scene. The pilgrims crossing in shot 6 provide a transition to the tilt up to the crutches (b) abandoned presumably by miraculously cured pilgrims.

CLOSE-UPS ARE YOUR MEAT AND POTATOES

Any shooter worth his lens cap understands that close-ups do most of the heavy lifting. That close-ups should play such a major role should not be surprising as television has been traditionally a medium of close-ups. With laptop computers and mobile devices becoming increasingly popular, the viewing limitations of a small screen are not likely to change; the smart shooter knows that effective stories in the future will continue to rely primarily on close ups to help focus and engage the viewer.

FIGURE 3.45

It’s not the amount of footage you shoot. It’s the coverage you provide! Partake heartily.

FIGURE 3.46a

A tear running down a cheek. This is a sad story.

FIGURE 3.46b

Getting married. This is the story of a happy couple.

FIGURE 3.46c

Zoe and Theo. This is one incredible love story.

I often describe my job as analogous to a plumber. To assemble a working system I need a range of fittings—a way in, a way out—plus the runs of longer pipe, that is, the close-ups that do most of the work and ensure functionality. Similar to the plumber with boxes of useless tees or elbows, the video storyteller can do little with umpteen cases of tapes or memory cards if he isn’t providing the range of shots to craft a compelling tale.

Just as a tiger won’t attack its prey too head-on, so, too, should you not approach your subject too directly. Sometimes a lazy cameraman will simply push in with the zoom to grab a close-up. This lazy close-up should be avoided, because the point of view becomes unclear and the story’s natural flow and shot progression are disrupted. Better that the camera come around and unmistakably enter one or the other character’s perspective.

FIGURE 3.47

Don’t just zoom in! Come around! The lazy close up is confusing because it has no clearly associated point of view.

SHOT PROGRESSION AND FRAME SIZE

The shooter-craftsperson understands the importance of shot progression and maintaining proper frame size. In narrative-type projects employing less professional gear, this can be a challenge because many cameras’ controls for zoom and focus preclude a high degree of precision from one setup to the next.

FIGURE 3.48

The story is in the close ups so most shooters want to get in close and stay close, widening out only to introduce a new character or event that moves the story forward.

The usual shot progression serves up a series of alternating singles of each actor and his respective point of view. If the talent on screen is not consistently sized or if the eyeline is not as expected, the viewer may become disoriented, and the visual story may stall.

To ensure continuity and a smooth, visual story, note the lens focal length and the distance for each setup by referencing a tape measure or a camera readout to ensure accurate placement of talent in subsequent close-ups or reaction shots.

In the campaign rally scene from Citizen Kane, the eyeline from below imparts great power and stature in the Kane character whereas the downward angle has the opposite effect. With multiple actors in a scene, the level and direction of an eyeline helps orient the audience to the geography and relative positions of the players. When shooting interviews, we generally place the camera slightly below eye level. This imparts the respect and authority we usually want without appearing heavy-handed or manipulative.

FIGURE 3.49

Who is heck is the actor at right looking at? Proper eyeline helps ensure a seamless continuity. In this case, the incorrect eyeline suggests a third character has entered the scene.

FIGURE 3.50

A documentary or news shooter must often adjust his position up or down to achieve the proper eyeline. Strong thigh muscles are a must!

FIGURE 3.51

In narrative projects, the focal length, f-stop, and subject distance from camera should be recorded for every setup. On a crowded set a cloth measure (not steel) is preferred because it is quieter, more flexible, and less likely to snap back and decapitate an actor.

SHOOTING THE LESS THAN PERFECT

Eyeline can also serve to de-emphasize shortcomings in an actor’s face. A double chin or broad large nostrils are much less noticeable with the camera set slightly above eye level. Conversely, a self-conscious man with thinning hair might appreciate a lower eyeline that reduces the visibility of his naked pate.

Here are a few tips to handle more potentially delicate issues:

• Shooting someone with an unusually long nose? Consider a more frontal orientation. For someone with a broad, flat nose consider more of a profile.

• Shooting someone uncomfortable with a facial scar or disfigurement? Turn the imperfection away from camera. If this is not possible, reduce the camera detail, use a diffusion filter, and/or light flatly and frontally to reduce texture in the face.

FIGURE 3.52a

Be careful. In the case of some actors an unusually long nose may BE the story!

FIGURE 3.52b

Facial scars and other imperfections may help support an actor’s character. Use caution when mitigating, and let the story be your guide!

FIGURE 3.53

Working with a narcissistic screen star? Be sure to study his or her facial features to determine the most flattering perspective. This is excellent career advice for the aspiring shooter!

The smart shooter is eager to exploit cues within the frame to more effectively convey the visual story. At public events, protests, and film festival screenings, a plethora of signs and placards can often be seen amid the crowd; use such native elements to give your story impetus and clearly establish the point and the point of view of a scene.

FIGURE 3.54

Signage, newspapers, and handwritten placards are great communicators of story. Look to exploit such organic elements whenever possible.

FIGURE 3.55

The “story” of this Uganda school is inscribed on the buildings’ walls.

BACKGROUNDS TELL THE REAL STORY

It came as a revelation to me that backgrounds often communicate more than foregrounds or even the subject itself. This is because audiences are suspicious, continuously scanning the edges of the frame for story and credibility cues: Are they supposed to laugh or cry? Feel sympathy or antipathy? Believe what someone on screen is saying or not? The audience seeks such cues in order to determine the truth of a scene.

Poor control of background elements may undermine your story and may communicate the opposite of what you intend. In the 1970s, I recall a radical soundman friend who invested every dollar he earned in pro-Soviet propaganda films. His latest chef d’oeuvre sought to equate Watergate-era America with Nazi Germany and to ultimately open the minds of Westerners to the enlightened Soviet system. The world has changed since 1976, and few folks would care to make this movie today, but at the time, intellectuals ate this stuff up.

Now, you have to remember this guy was a soundman, so it was understandable that he would focus primarily on the audio story. Indeed, the film was little more than a series of talking heads of out-of-touch university professors and fellow radicals. I recall one scene in front of an auto plant in the Midwest. The union foreman was railing against his low wages: “Capitalism is all about f—ing the working man!” he ranted.

Not surprisingly, the message and film played well in the Soviet Union where officials were eager to broadcast the anticapitalist message on state television. When the show aired, it drew a large appreciative audience much to the delight of government apparatchiks and the filmmaker, but not for the reason they imagined.

In the scene at the car plant, the foreman came across as compelling. His remarks were well expressed, and he sounded sincere. But Soviet audiences were focused on something else. Something visual.

In the background by the entrance to the plant, viewers could glimpse a parking lot where the workers’ cars were parked. This was unfathomable to the Soviet workers at the time that the employees could actually own the cars they assembled. To Russian audiences, the workers’ cars in the background told the real story; that glimpse and the tiniest fragment of the frame completely undercut what the union foreman was articulating.

So the lesson is this: The most innocuous background, if not duly considered, can have a devastating effect on the story you’re trying to tell. When you take control of the frame, you take control of your story!

FIGURE 3.56

Is this rickshaw driver pulled over on a busy street or stranded in the middle of nowhere? Background elements not serving the intended story must be removed or de-emphasized.

As honest and scrupulous as we try to be in our daily lives the successful shooter-storyteller is frequently required to misrepresent reality. Skateboard shooters do this all the time, relying on the extreme wide-angle lens to increase the apparent height and speed of their subjects’ leaps and tail grinds.

I recall shooting (what was supposed to be) a hyperactive trading floor at a commodities exchange in Portugal years ago. I’ve shot such locales before, with traders clambering on their

desks while shrieking quotes at the top of their lungs. This was definitely not the case in Lisbon, where I found seven very sedate traders sitting around, sipping espressos, and discussing a recent soccer match.

Yet a paid assignment is a paid assignment, and I was obligated to tell the client’s story, which included capturing in all its glory the wild excitement of what was supposed to be Europe’s latest and most vibrant trading floor.

So this is what I was thinking: First, I would forget the wide angle. Such a perspective would have only made the trading floor appear more deserted and devoid of activity. No, this was clearly the time for the telephoto to narrow and compress the floor space to take best advantage of the few inert bodies I had at my disposal.

By stacking one trader behind the other, I created the impression (albeit a false one) that the hall was teaming with brokers. Of course, I still had to compel my laidback cadre to wave their arms and bark a few orders, but that was easy. The main thing was framing the close-ups and filling them to the point of busting, suggesting an unimaginable frenzy of buying and selling outside the frame. The viewer assumed from the frenzy of the close-ups that the entire floor must be packed with riotous traders when, of course, the reverse was true. What a cheat! What a lie!

So there it is again: What is excluded from the frame is more critical to the story than what is included! Exclude, exclude, exclude!

FIGURE 3.57

The shooter-storyteller is often required to creatively interpret reality. Using tight framing, a long lens, and abundant close ups, this nearly abandoned trading floor appears full of life.

FIGURE 3.58

Psst. The “speeding” train isn’t actually moving. What a lie! What a cheat!

Question from reader: My boss thinks he looks fat on camera. Do you have any tried and true ways to make him look and feel thinner on camera? I can’t shoot him above the waist or behind a desk all the time.

Barry B. responds:

One suggestion: Light in limbo. The less you show, the less you know! You can use a strong sidelight to hide half his mass. Keep it soft to de-emphasize the fat rolls. You can also add a slight vertical squeeze in the NLE [nonlinear editor]. A few points in the right direction can work wonders!

FIGURE 3.59a

Shooting the rotund (before).

FIGURE 3.59a

Shooting the rotund (after).

FIGURE 3.59b

Applying the squeeze. Hey, it’s a lot quicker than Jenny Craig!

It’s frustrating to work with directors who don’t know what they want, and unfortunately these days, the business attracts them in droves. One reason may be simply the increased number of low- and no-budget productions as newbie directors think it’s somehow OK not to do their homework when the financial stakes are low. The experienced shooter can help these shopper types choose a direction by clearly defining the visual story well before the first day of shooting.

A director’s storyboard encapsulates the visual story and helps communicate that vision to the crew.

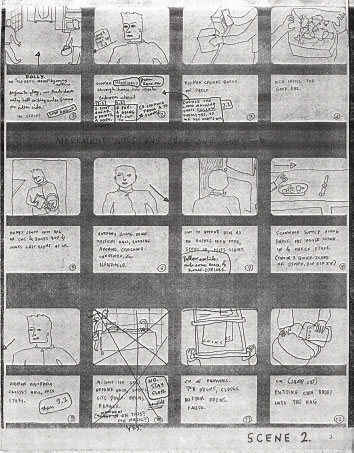

FIGURE 3.60

No shopping allowed! If you’re a director, do your homework, know what you want and communicate it to your collaborators. A shooter needs clear direction to do his or her best work!

FIGURE 3.61

A director’s storyboard is a blueprint of the visual story and shot progression.

The ability to manage and survive difficult personalities is a skill worth developing. On any given production, you’re likely to encounter these types—maybe you’re one yourself—so it stands to reason that shooters should acquire the interpersonal skills necessary to collaborate most successfully.

I know a lot about this subject because I used to be one of these difficult people. I took myself way too seriously. Sure I was good at what I did and was widely recognized for it. But I was also a prick. And it cost me in my relationships, the quantity and the quality of my assignments, and the evolution of my craft. It was bad for me on all fronts.

It’s no secret that strong personal and professional relationships contribute to our success as a video shooter. This is a business after all where freelancers rule the roost, and most of us work from project to project and client to client. We rely on our relationships almost entirely for our financial and creative wellbeing.

In my own career spanning more than 30 years, I’ve never had a staff job. As a freelancer, I know one phone call can change my life and whisk me off to some exotic land. This may sound exciting and it is much of the time, but it is also highly unpredictable. No wonder then that freelance shooters in general are such a fearful and insecure lot.

Thus, I have learned only late in life how important it is to separate who I am from what I do. Whether you’re an actor, a writer, a director, or a cameraperson, rejection is inevitable. When my collaborators reject my work or ideas, it is only me as a cameraman and not me as person who is being repulsed. Yes, I am an artist skilled in my craft and I understand that completely, but I am also able to listen and respond constructively to a collaborator, even when disagreeing to the core with his or her opinions or unreasonable dictates.

FIGURE 3.62

Egomaniacs. Deal with them. Learn from them. Don’t include yourself among them.

FIGURE 3.63

Disagreements with collaborators are part of the creative process. How you handle these conflicts is pivotal to your success as a shooter-storyteller, and human being.

Once I adopted this attitude, I was finally able to grow as an artist. In fact, many of my collaborators’ suggestions that I thought asinine at the time I now consider strokes of genius and have integrated them into my craft and into this book! I am a better shooter and a happier human being for it.

EDUCATOR’S CORNER: REVIEW TOPICS

1. Consider the video shooter’s mantra to exclude, exclude, exclude! Explain how this principle might apply to other cinema crafts—direction, script, sound, acting, and editing. The shooter is not alone seeking to exclude elements that may interfere with a compelling story.

2. Explore the wisdom of making your viewers suffer. What strategies can you use—focus, lighting and composition—to pursue this noble goal?

3. Think about the critical role of close-ups to convey effective visual stories. Some directors do not use close-ups and are nevertheless successful. How do you explain this? What other factors might be in play?

4. Discuss the storytelling implications of eyeline and camera placement in the following scenes: an interrogation in a police station, a political rally, a mother reprimanding her child, and a day in the life of a dog.

5. Every video shooter is a liar. Do you agree?

6. Los Angeles is frequently used as a stand in for New York. The look and light are much different. How do different textures of light impact the visual story?

7. Identify and photograph six (6) triangles in the world around you. Are the triangles subtle or relatively obvious? Is there any point to this exercise?

8. Egomaniacs are some of the most successful artists and businessmen in the world. Is egomania the price we must pay to excel at the highest levels of our craft?

1 See Chapter 4 for a discussion of the brain as a digital signal processor.

2 See “3D Shooter” in Chapter 7 for an in-depth discussion of “monoscopic” versus “stereoscopic” depth cues.

3 Depth of field (DOF) may be defined as the range of objects in a scene from near to far that appear in sharp focus.

4 Warner, J. L. (Producer), Wallis, H. B. (Producer), & Curtiz, M. (Director). (1942). Casablanca [Motion picture]. USA: Warner Bros.

5 Welles, O. (Producer & Director), & Schaefer, G. (Producer). (1941). Citizen Kane [Motion picture]. USA: RKO Radio Pictures.