So you’re outputting your show for the Web, mobile phone, or DVD, and you face the following option: Would you prefer good, better, or best?

Hmm. I wonder why would anyone settle for good or better when you can have best? Best is definitely better than better, and better inherently has to be better than good. On the other hand, I suppose it’s a good thing that worse is not an option, because worse is surely worse than good, but it is better than much worse, and much, much better than much, much worse.

All this mental wrangling raises the greater issue: Can there ever really be a Best button?

A Best button certainly has its appeal. We wouldn’t need to spend a lifetime learning lighting, composition, framing, how to use texture and perspective or understanding the intricacies of the animal brain. We wouldn’t have to learn the technical razzmatazz, the aesthetic subtleties, and silly names for things on sets. We could forego the stress and discipline of having to exclude, exclude, exclude all the time. A Make It Awesome button could do it all for us.

I recall 15 years ago working with Master Tracks Pro, a popular sequencing program for quasi-serious musicians. The program offered a humanize feature I hadn’t seen before and haven’t seen since. Now as it turns out, I’m a really rotten piano player and I play in the most mechanical way. When I see a quarter note, I play the quarter note precisely as written without a lot of interpretation. So the program worked great for me. After one of my robotic performances devoid of feeling, I’d add a dash of humanization and presto—an inspired musical tour de force worthy of Carnegie Hall!

Well no, not really. The program didn’t really produce anything inspired at all; it merely moved my regular quarter notes off the beat by some random amount. This had the effect of transforming my machinelike performance into the work of someone simply playing badly—hardly the makings of a virtuoso.

FIGURE 14.1

Hmm. A tough choice. Assuming you have any self-respect at all, which would you choose?

It stands to reason that a story in whatever medium cannot be fashioned in an automatic way according to a generalized algorithm. Stories with nuance and taste must be individually crafted and finessed; for all the technical mumbo-jumbo we spew about in this book and elsewhere, our digital-powered video stories are emotional experiences as far from the soulless technology as we can get.

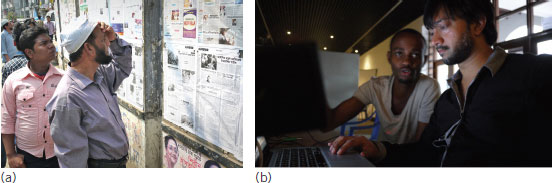

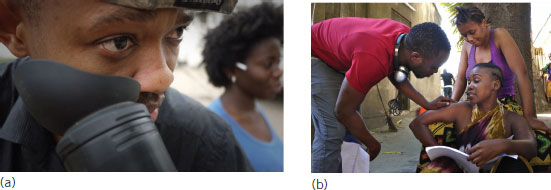

FIGURE 14.2

Effective storytelling requires forming a personal bond with our audience. The task can be challenging. We need collaborators.

It permeates our brains. It frames the questions we pose, the discussions we pursue, and the opinions we espouse. Currently we are seeing enormous pressure on manufacturers to produce cameras with large very high-resolution sensors. But is this what we really want or need? Why is more resolution better? The 2K ARRI Alexa has become the standard for big-budget Hollywood films projected on 60-foot cinema screens, yet many shooters of far less demanding fare won’t settle for anything less than 4K original capture. Damn the expense and nightmare workflow, they say, this is what they want—the more resolution the better—8K? 10K? 12K? Where does it end?

FIGURE 14.3

Understand what really matters. It’s not a camera with a sensor the size of a battleship.

FIGURE 14.4

If operation or workflow is too convoluted, we won’t use a camera regardless of its sensor size or resolution claims.

Our audiences aren’t counting pixels on a screen or assessing our ability to capture the most stunning resolution test chart. Our stories fraught with human emotion and nuance are hopefully more interesting than that.

What we really want is a camera that offers superior color fidelity, smooth gradients, and sharp clean images, combined with efficient operation and workflow. The hype says pay attention to sensor size and pixel count; the craft says pay attention to optics. Choice of lens is far more critical and relevant to the success of our visual story, especially given the more than adequate resolution from most HD and 2K cameras these days.

The hype of the Internet and fretful online boards can lead us to believe we need much more than we do. The chatter mills remind us constantly that somehow we don’t measure up, that our camera doesn’t have enough pixels, that the sensor isn’t big enough, or our shooting 4:2:0 will reduce us to gutter trash.

The truth is we need don’t need much to do outstanding work. I learned this lesson from a shipyard worker wrapped in rags shooting 8mm video newsreels in 1987 Poland. I learned it in 2007 from a Tanzanian filmmaker shooting a police drama without a single working light. And I learned it in Cairo in 2011 from a genius young director who fashioned the most remarkable, touching story of an artist painter and young boy set amid the chaos of revolution and mayhem in the streets. Regardless of the project, we all do better, much better, to resist complexity whenever we can.

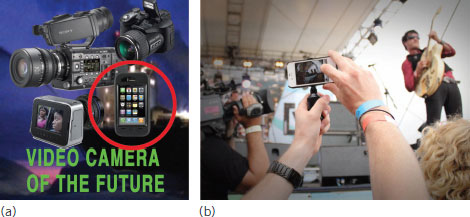

FIGURE 14.5

The current large-sensor-narrow-depth-of-field fad will soon pass. Next up … the ease and simplicity of the smartphone.

FIGURE 14.6

The camera in your hand right now is perfect. It’s perfect because it’s yours. You don’t need more.

FIGURE 14.7

Do we really need a truck full of gear to light a scene well? Probably not.

In regions of the world that lack broadband connectivity, there has been an explosion of tiny viewing parlors called bandas. These micro-theaters can be as simple as the back of a van in Nigeria or the corner of a ramshackle home in Bangladesh. The advent of tiny screens in bandas and in mobile devices is transforming the medium and how audiences see and appreciate our work. The presentation of cinema, TV, and all style of programs is becoming more intimate and personally directed at the viewer.

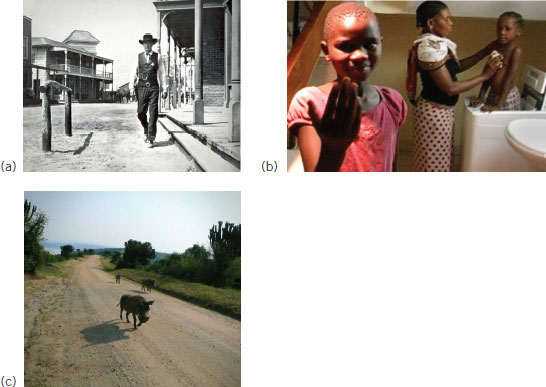

FIGURE 14.8

There is disruptive change in the air. The cameras and massive storytelling machines of yesteryear are disappearing fast.

FIGURE 14.9

A local viewing hall in small town Uganda.

FIGURE 14.10

The iPhone’s small screen strongly favors close-ups, so you have yet another reason to use close-ups to tell visually compelling stories.

Today’s cameras are lighter and more compact, with a wider dynamic range so we need fewer lights, which means smaller crews, fewer grips, and fewer hungry Teamsters. Routine editing and digital effects can be done on a laptop while sitting on a sofa, which means fewer post houses and fewer high-paid specialists. Add to that the self-distribution of titles via the Web, and it’s easy to see the reduced need for manpower from studio grips to studio chiefs.

FIGURE 14.11

From Hollywood to Swahiliwood, if you tell compelling visual stories, they will come. They always have. They always will.

It’s a dog-eat-digital world out there, and some of us will always be more talented than others in lighting it and framing it. For folks able to capture the most compelling visual stories there will always be a demand for these specialists. But for everyone else and for the vast majority of shooters today, the economics of digital media are such that adept use of the camera is just one element in a much greater skill set. To stay relevant, today’s shooter must understand and embrace the entire process from the script and storyboard through shooting and display in a cinema or streamed via the Web. The process is long and complex, and the shooter who understands it all, the opportunities and perils, will continue to do well wherever the journey may take him.

FIGURE 14.12

Filmmaking is a collaborative process. Whoever makes the most mistakes wins!

FIGURE 14.13

Go forth, dear shooter. Travel the world and seek great footage and capture great stories. Our job and responsibility is to harness that power and use it effectively, creatively, and wisely.

FIGURE 14.14

EDUCATOR’S CORNER: REVIEW TOPICS

1. Following up this question from Chapter 1: Identify three (3) feature films or documentaries that changed the world for better or for worse. Your examples need not be well-known works or even a single work. Explain the impact of each film at the time and on the course of history.

2. Describe the range of skills that today’s shooter should master, from Photoshop and green screen to speaking multiple foreign languages. Not to sound mean, but if you’re in school, are you studying the right things?

3. List five (5) strengths that you possess as a filmmaker. How do these skills infuse in you a unique storytelling perspective?

4. Identify three (3) feature films or documentaries with significant visual shortcomings. Describe how these shortcomings might positively or negatively impact the viewer experience.

5. The story of your life is not your life—it’s a story. Consider your own life story with two different scenarios. Create a poster and log line for each. Is your life a drama or a comedy? Is the premise compelling? Is the protagonist someone with whom your audience would like to spend two hours? At $12 per ticket, which version of your life do you think folks would more want to see in a theater?

6. Describe the different looks for versions I and II of Your Story. Consider lens choice, diffusion, depth of field, color balance, and lighting. How much of a factor is genre when determining Your Story’s look?