1 |

Dear Video Shooter:

This is your task. This is your struggle to uniquely and eloquently express your point of view. Whatever it is. Wherever it takes you. For the shooter-storyteller, this exploration can be exhilarating and personal. It’s what makes your point of view different and enables you to tell visually compelling stories like no other video shooter in the world.

In May 1988 while on assignment for National Geographic in Poland, I learned a profound lesson about the power of personal video and point of view. The aging Communist regime had amassed a thousand soldiers with tanks in front of the Gdansk Shipyard to crush a strike by workers belonging to the banned Solidarity union. I happened to be shooting in Gdansk, and despite it not being part of my assignment I ventured over to the shipyard anyway in light of the world’s attention being focused there and the compelling human drama unfolding inside.

Out of sight of my government minder, I understood I could’ve been beaten or been rendered persona non grata, but I took the chance anyway as I was convinced that history was in the making. The night before, the military had stormed a coalmine in southern Poland and had brutally beaten many strikers as they slept. Not a single photo or frame of video emerged to tell the tale, but news of the carnage spread anyway through unofficial channels. The shipyard workers figured they were in for the same fate, and I wanted to record it.

Considering the regime’s total control over the press and TV, it was no surprise that the Polish InterPress Office would deny my 16mm Arriflex and me access to the shipyard. But that didn’t stop my two Polish friends with less obvious video gear from slipping inside the complex in the back of a delivery van.

Throughout the previous fall and winter, Piotr Bikont and Leszek Dziumovicz had been secretly shooting and editing half-hour newsreels out of a Gdansk church loft. Circumventing the regime’s chokehold on the media, the two men distributed the programs through a makeshift network of church schools, recruiting young school kids to ferry the videocassettes home in their backpacks.

As this latest shipyard drama unfolded, Piotr and Leszek vowed to stay with the strikers to capture the assault and almost certain bloodbath. Piotr’s physical well-being didn’t matter, he kept telling me. In fact, he looked forward to being beaten, provided he could get the footage out of the shipyard to me, and to the watchful world.

But for days and weeks the attack didn’t come, and Piotr and Leszek held their ground, capturing in riveting detail the exhaustion of the strikers as the siege dragged on. In scenes reminiscent of the Alamo, 75 men and women facing almost certain annihilation held firm against a growing phalanx of tanks, troops, and feckless provocateurs who occasionally feigned an assault to probe the strikers’ defenses.

In the course of the siege, Piotr and Leszek made a startling discovery that their little Sony camcorder could be a potent weapon against the amassed military force. On the night of what was surely to be the final assault, the strikers broadcast a desperate plea over the shipyard loudspeakers: “Camera to the gate! Camera to the gate!” The strikers were pleading for Piotr and Leszek to come with their camera and point it at the soldiers. It was pitch dark at 2 a.m., and the camera couldn’t see much. But it didn’t matter. When the soldiers saw the camera pointed at them, they retreated. They understood the inevitability of a postcommunist Poland and were terrified of having their faces recorded!

FIGURE 1.1

Solidarity activists Piotr Bikont and Leszek Dziumowicz with the Sony camcorder that helped transform the face of Eastern Europe in the 1980s.

As the weeks rolled by, the strikers’ camera became a growing irritant to the authorities. Finally, in desperation, a government agent posing as a striker ripped the camera from Piotr’s arms. After a frantic chase, the agent ducked into a building housing several other agents, not realizing, incredibly, the camera was still running!

Inside a manager’s office, we see what the camera sees: a drab blank wall as the camcorder pointing nowhere in particular dutifully records the gaggle of agents plotting to smuggle the camera back out of the shipyard. The camera is then placed inside a paper bag, and the story continues from this point of view: The screen is completely dark as the camera inside the bag passes from one set of agents’ arms to another. Alas, the image wasn’t much—a black screen with no video at all—conveying a story to the world and a point of view that would in short order devastate the totalitarian regime.

FIGURE 1.2

When an undercover agent suddenly grabbed Piotr’s camera, no one thought about turning the camera off!

FIGURE 1.3

What’s this? A dark screen? If the context is right, you don’t need much to tell a compelling story!

FIGURE 1.4

In this pivotal scene from Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), we listen to mostly unseen characters in a dark projection room. Suppressing visual content in this way forces an audience to listen, this strategy being very effective to communicate critical dialogue or exposition

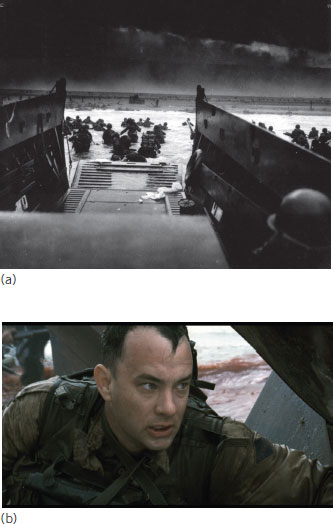

FIGURE 1.5 a,b

Conversely, we can force the viewer to focus more on the visual story by attenuating or eliminating the audio entirely. Managing the interplay of picture and sound is the essence of a filmmaker’s craft. (b) The muted audio in this scene from Saving Private Ryan (1998) reinforces the horror of the D-Day beach landing at Normandy.

FIGURE 1.6

Ninety percent of a video story is communicated visually. Given a choice, viewers always prefer to watch than to listen. They cannot do both at the same time!

FIGURE 1.7

Show me; don’t tell me! Great storytelling requires compelling visuals!

I’m often asked, “Which camera should I buy?” and “Which camera is best?” These questions are loaded and often laced with fear. My answer is always the same: It’s the camera that best supports the point of view of the story you’ve chosen to tell.

There are always trade-offs in whatever camera you choose, and you should be leery of selecting a make or model based on a single feature such as imager size or resolution. High-resolution cameras may have associated drawbacks like inferior low-light response, constrained dynamic range, and a bevy of shuttering artifacts owing to their large CMOS 1 sensors. These compromises along with a data-intensive workflow can have a negative impact on your filmmaking efforts, so is the highest resolution camera really what you want or need to convey your visual story and the desired point of view?

If a close-focus capability is crucial for your documentary work, then a small compact camcorder with servo focus may be preferable to a full-size model with manual optics. Pricey broadcast lenses will almost always produce sharper, more professional images, but they cannot usually focus continuously to the front element owing to the limitations of their mechanical design.

There is no perfect camera for every application. Every model has its strengths and weaknesses, the compromises in each camera being more apparent at lower price points. If you really know your story and the intended point of view, you can select the right camera, which need not be the most expensive or sophisticated. Similar to a carpenter, a plumber, or an auto mechanic, the smart shooter understands his or her tools and how they may advance (or hinder) his or her goals as a craftsperson. 2

FIGURE 1.8

Shooting on a public pier without a permit? A consumer Canon HF-S100 or DSLR may be ideal. Shooting a documentary for The Discovery Channel about the mating habits of the banded mongoose? The full-size camcorder with variable frame rates and a smallish 2/3-inch sensor is perfect. Secretly capturing passenger confessions in the back of a Las Vegas taxi? The lipstick camera or even the Go Profits the bill. When it comes to gear, your story and intended point of view trump all other considerations!

The notion of a shooter as a dedicated professional has been eroding for some time. For several hundred dollars and little or no training, almost anyone with a low-end Canon, Panasonic, or late-model iPhone can produce reasonably decent video, which makes for ugly competition among shooters no matter how talented or inspired we think we are.

For the shooter-storyteller to prosper in the current environment he or she must become a 21st-century Leonardo DaVinci. Classical painting, printing presses, and helicopter designs may not be our areas of expertise, but the trend is clearly toward craftspeople who can do it all: shoot, write, edit, produce, and design websites. These days, increasingly, we’re talking about the same person.

Just as strands of DNA compose the building blocks of life and heredity, so too do zeros and ones constitute the essence of every digital device and application. Today’s shooter, whether inclined to or not, must embrace the new hyper-converged reality. Whether you’re a shooter, a sound recordist, a special effects artist, or a music arranger, it doesn’t matter. Fundamentally, we’re all manipulating the same zeros and ones.

Thirty years ago on the Hawaiian island of Maui, I spent an entire afternoon chasing a rainbow from one end of the island to the other, looking for just the right combination of background and foreground elements to frame the elusive burst of color. It was, in many ways, a typical assignment for me circa 1985.

Today, I don’t think many producers for National Geographic or anyone else would care to pay my day rate for a Wild Rainbow Chase. Why? Because producers versed in the digital tools are far more likely to buy a stock shot of the Hawaiian landscape (or create one in Bryce 3D) and then add the rainbow in Adobe After Effects!

These folks like the rest of us are learning to harness the digital beast, and whereas past shooters were responsible for creating complete finished frames, today’s shooters are more apt to furnish only the frame elements for rearranging and compositing later by a multitude of downstream creative types. After completion of principal photography for The Phantom Menace (1999),3 George Lucas is said to have removed unwanted eye blinks from his stars’ performances. Alas! No one is safe in this digital run-amok world! Not even actors!

In my camera and lighting classes, I recognize that my students are receiving training at a feverish pace. And what are they learning? To composite, reposition, and alter the color and mood of scenes; to crop, diffuse, and manipulate objects in three-dimensional (3D) space; to align, mix, and dub audio tracks—in other words, to do the combined jobs of an entire production and postproduction staff!

In August 2006, director Wes Anderson (Moonrise Kingdom, Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums) asked me to shoot behind the scenes for The Darjeeling Limited,4 a story of three brothers aboard an Indian Railways train chattering across the Rajasthan desert. Wes didn’t want just an ordinary behind the scenes (BTS) show. Instead he suggested a more engaged approach, one in which my presence as a shooter and an interlocateur would figure prominently.

To fund the project and my five months in India, Fox Searchlight drew on the resources of multiple studio divisions: Publicity, Home Video, Marketing, and the Web. That’s how I came to wear several hats: shooting second unit for the movie and editing and producing a 1-hour HBO special, a 30-minute featurette for DVD, 16 podcasts for the website, and 6 EPK (electronic press kit) interviews of the director and cast for distribution to entertainment news outlets. So you see I was no longer just a shooter but an ersatz producer/editor/DVD author and a Web content specialist!

FIGURE 1.9

Prowling the streets of Jodhpur, India. A full-size camcorder is ideal for shooting high-detail city scenes and landscapes.

FIGURE 1.10

A versatile go-anywhere camera greatly expands the shooter’s storytelling palette.

FIGURE 1.11

The Darjeeling Limited (2007). Here I double for Bill Murray inside a taxi racing to the Jodhpur train station. The camera beside me offers audiences a unique point of view for the behind the scenes show.

During the last 10 years, advances in technology have transformed the capabilities of the camera, so much so that today even the most inexpensive camcorder is able to produce excellent images. Given this context for a shooter to be successful, it’s no longer a matter of who owns the tools; it’s who owns the craft.

Becoming proficient in the craft was simpler for shooters a few decades ago. We lived in a mechanical world then, which meant when our machines failed, we could look inside and figure out how they worked. We could remedy a problem and gain confidence and ability without having a theoretical understanding of bit theory or the inside track to someone at MakeItWork.com.

In past years the aspiring shooter dutifully pawed over Joseph Mascelli’s masterwork The Five C’s of Cinematography,5 which described in exhaustive detail the rudiments of effective visual storytelling. The mastery of the Five Cs—camera angles, continuity, cutting, close-ups, and composition—was imperative as shooters had to consider the implications of every creative and technical decision before rolling the camera, or face severe, even crippling, financial pain.

I remember my struggle to raise money for a PBS documentary in the 1970s. After months of frustration and finally landing a grant for a few thousand dollars, I can still recall the anxiety of running film through the camera. Every foot (about a second and a half) meant 42 cents out of my pocket—a figure forever etched into my consciousness. And as if to reinforce the sound of my dissipating wealth, the spring-wound Bolex would sound a mindful chime every second on its maximum 16.5-foot run.

The technology (or lack thereof) imposed its own discipline, and so by necessity, every shot had to tell a story with a beginning, middle and an end. Every frame, composition, lens choice, and background, had to be duly considered. A skilled cameraperson able to manage all this was somebody to be revered and remunerated. It is still this way for the multidimensional shooter of today, albeit the discipline of the craft must now be mostly self-imposed.

FIGURE 1.12

My ’66. When it didn’t start, you pushed it. No understanding of MXF, USB, or eSATA required.

FIGURE 1.13

The San Francisco cable car is the ultimate expression of the mechanical world we once knew and loved.

FIGURE 1.14

The spring-wound camera propelled a perforated band of photosensitized acetate around a series of sprockets and gears. The mechanism was easy to see, study, and troubleshoot.

FIGURE 1.15

The manual nature of film cameras imposed a discipline not as readily gleaned from auto-everything digital camcorders.

The DV revolution transformed the medium by empowering ordinary people to engage their passions and express their points of view in venues such as Facebook and YouTube. Out of this, we are seeing the incarnation of a new breed of shooters to whom we can now credit a litany of work including feature films captured in whole or in part with inexpensive camcorders and digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras: Super Size Me (2004),6 Once (2006),7 and Act of Valor (2012),8 shot almost entirely on the Canon 5D Mark II.

FIGURE 1.16

The DSLR as a serious imaging tool came of age with Act of Valor (2012). The sprawling action film grossed more than $200 million worldwide.

The Five Cs hallowed cinematographic principles may be more relevant than ever, but look who is applying them! It’s not just shooters. It’s anyone with a hand in the creative process: editors, directors, 3D artists, DVD menu designers—anyone with a Macintosh, a PC, or even an iPad, and that covers just about everyone.

Currently major U.S. news shows are moving rapidly to a one-person-does-it-all model, as show runners and correspondents are being increasingly asked to shoot, record sound, and in some cases even edit their own segments.

In smaller markets and for cable TV, the solo shooter-storyteller is already commonplace. Several years ago, I was asked to shoot several episodes for The History Channel’s Sworn to Secrecy series. My first assignment required that I fly with the crew to Spokane, Washington, to interview air force pilots undergoing wilderness survival training.

Of course, in shooting such a series, I naturally assumed that audio would be a priority. So on the plane out of Los Angeles, I couldn’t help but notice that my “crew” was rather small, consisting in fact of only the 22-year-old director and myself. I expressed astonishment to my boyish colleague, who thought for a moment, then smiled. I looked at him like he was nuts.

“I don’t know why you’re so happy,” I said. “We’re doing hours of interviews and we’ve got no soundman.”

“Yes,” he said, his eyes shining brightly. “But I’ve got a cameraman!”

It was then I finally understood the digital revolution. This newbie director had been hired to write, direct, shoot, and edit a 1-hour show for an award-winning TV series. It was a fantastic opportunity for the budding director; the project drawing hugely on his extraordinary skill set, but it did make me wonder about the shooter’s role in the future, and whether that role would ever really stop expanding into other disciplines such as sound.

FIGURE 1.17

Thinking about the future and the role of the video shooter? Me too.

Gaining the requisite camera skills takes lots of practice and ample work opportunities. For many folks, the latter point is the bugaboo that may require a new and more radical point of view. First, we must realize that the shooter-craftsperson cannot compete on price. Whatever rate you quote no matter how low, someone will always offer to do the job for less. If you say you’ll shoot a project for $100 per day, someone with the same DSLR will bid $50. And if you bid $50, someone will offer to do it for $25, and so forth. Working cheap is never in your interest, unless of course that is what you want to be known for working cheaply. But working for free—that can be such a beautiful thing!

It may seem counterintuitive or even insane, but consider this: Working for free is not the same as working cheaply. Working at less or much less than the prevailing rate lowers the value of your services and diminishes your stature in the eyes of a client. It exposes you to a range of abuses, long hours, and lack of respect. But working for free is a totally different matter. Now you hold the power, not your employer, because you’ve hired him. You’ve selected him or her above all others, so this person owes you, and that shifts the relationship dynamic in your favor.

So this is it. First, you identify your dream job and you go after it. You cajole. You charm. And most of all you persevere. Once you land it, you work for free yes, but you also work hard until you are indispensable. You then write what amounts to a ransom note and threaten to leave, at which point your client/employer will likely offer you a paid position, and you say … what? You say no.

That’s right. Instead you say, “Gee, I would really like to work for you and am so excited about this opportunity, but you can’t afford me.” So you turn your boss down. Whatever he or she offers, you’re not interested. Folks, this is psychological warfare. The moment your boss lets you become indispensable, you’ve already won. There’s no point in compromise. You can dictate your own terms.

This is how Hollywood and probably many other industries work. More important than the money, executives are mostly fearful of hiring the wrong person. Such a faux pas can be costly, embarrassing, or even calamitous, for risk-averse execs. On the other hand, if you’ve demonstrated with passion and confidence that you are the right person for the job, that all they have to do is hire you and their worries are over, you have eliminated their fears, which can only lead to good things, including financial rewards. If you choose your employer carefully, the days you work for free can be among the most lucrative of your career.

Thanks to the latest low-cost cameras and the ability to reach hundreds of millions via the Internet, the shooter today wields more power than ever. You can use this power for nefarious or unsavory ends as some shooter-storytellers do, or you can use it to transform the world and create works of lasting beauty for the betterment of humankind. It all depends on your point of view and the stories you choose to tell.

EDUCATOR’S CORNER: REVIEW TOPICS

1. Consider a recent news event in which the presence of a camera played a vital role. Did the camera offer a point of view that wouldn’t have been available otherwise? Is the camera’s point of view more valid than, say, a witness’s direct testimony?

2. Is a point of view necessary to create a compelling work? Is a documentary devoid of a point of view possible, given the inevitable shot selection, framing, and editorial choices?

3. Explore the advantages and disadvantages of a shooter wearing multiple hats. Do you feel that this compromises the effectiveness of the cameraperson?

4. Identify three (3) scenes from favorite movies that expertly manipulate picture and sound to maximize the story’s impact. Is the handling of sound more critical to a movie’s success than managing the picture? Please explain.

5. The proficient shooter often manipulates point of view for maximum storytelling impact. Cite three (3) examples from recent films in which the point of view was deliberately obscured to increase suspense or to add humor.

6. The video shooter has the capability to influence the world in profound ways. Cite three (3) feature films or documentaries that singularly transformed the political or social landscape.

1 Complementary metal–oxide semiconductor, a digital sensor as compared to analog CCD sensors. See Chapter 4 The Storyteller’s Box.

2 See Chapter 4 for in-depth discussion of how to evaluate camera operation and performance.

3 Lucas, G. (Producer & Director) & McCallum, R. (Producer). (1999). Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace [Motion picture]. USA: LucasFilm. Note that source information for films is provided on first mention only.

4 Ferozeuddin Alameer, S. M. (Producer), Anderson, W. (Producer & Director), Bamford, A. (Producer), Cooper, M. (Producer), Coppola, R. (Producer), Dawson, J. (Producer), … Rudin, S. (Producer). (2007). The Darjeeling Limited [Motion picture]. USA: Fox Searchlight Pictures.

5 Mascelli, J. (1998). The five C’s of cinematography: Motion picture filming techniques. Los Angeles, CA: Silman-James Press. (Original work published in 1965)

6 Morley, J. (Producer), Pederson, D. (Producer), Pederson, D. (Producer), Winters, H. (Producer), & Spurlock, M. (Producer & Director). (2004). Super Size Me [Motion picture]. USA: Kathbar Pictures.

7 Collins, D. (Producer), Niland, M. (Producer), & Carney, J. (Producer). (2006). Once [Motion picture]. Ireland: Bórd Scannán na hÉireann.

8 Clark, J. (Producer), Haggart, G. (Producer), Leitman, M. (Producer), Mailis, M. J. (Producer), McCoy, M. (Producer), Pollak, J. (Producer), … Waugh, S. (Director). (2012). Act of Valor [Motion picture]. USA: Bandito Brothers.