Chapter 6. Documents, Programs & Mission Control

The whole point of owning a computer, of course, is to run programs—or, as Apple likes to call them, apps. And in macOS these days, Apple wants programs to look and work like they do on the iPad: simply. As full-screen, autosaving worlds. You’re supposed to open them from a simple Home screen arrayed with app icons, and you’re supposed to switch among them by swiping with your fingers on a trackpad or mouse.

This radical new vision of running programs is actually possible—sort of. The hitch is that a lot of the iPaddy features, including Full Screen mode and autosaving, don’t work in all programs.

In any case, this chapter covers Apple’s Way of Running Programs, and all its Capitalized Elements: the Mac App Store, Launchpad, Mission Control, Full Screen, Auto Save, Versions, and more.

The Mac App Store

For years, people installed software onto their computers by buying disks: floppies, CDs, and, later, DVDs.

But starting with the iPhone, people installed software onto their phones by downloading it directly from the Internet. Once everybody saw how convenient (and profitable) that system was, it didn’t take Apple long to realize it could bring the same convenience to the Mac.

So now there’s the Mac App Store—or, as the program is called in your Applications folder, just App Store (Figure 6-1). It’s an online catalog of software from huge software companies, tiny one-person software companies, and everything in between. You can read about the programs, check out customer reviews, and download them directly to your Mac. (As you probably know, High Sierra itself is an App Store download.)

There are some huge advantages to this system. Since there’s no box, disc, registration card, shipping, or stocking, the software can cost a lot less; Apple’s own programs certainly reflect this price advantage. Plenty of programs in the App Store are actually free.

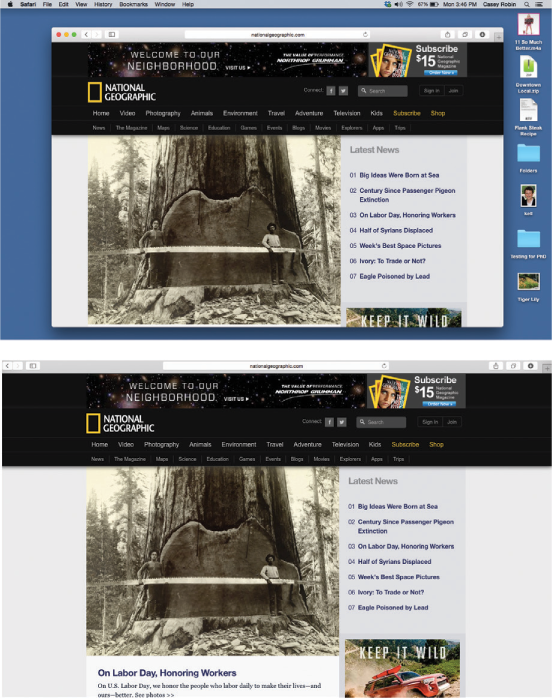

Figure 6-1. Top: Mastering the App Store won’t take you long; just about everything you need is in the toolbar at the top, including a search box and buttons like Featured, Top Charts, and Categories, which are meant to help you dive into the catalog of Mac software. The Purchased tab shows everything you’ve bought, for easy re-downloading. The final button, Updates, is where you’ll find new versions of your apps.

Bottom: You can read reviews of each piece of software, written by other people who’ve tried it.

Furthermore, Apple controls the transaction on both ends—it knows who you are—so there are no serial numbers to type in. The installation no longer interrupts you with warnings like “Please enter your password to install this software” or “This software appears to have been downloaded from the Internet.” Once you click Buy, the software downloads and installs itself automatically, without any interaction from you.

And there are no discs to store and hunt down later. If you ever get a new Mac, or if you ever need to reinstall a program from the App Store, you just re-download it from the Purchases tab; the App Store remembers that you’re a legitimate owner. Better yet, you’ll be downloading the latest version of that program; you won’t have to install all the “.01” patches that have come along since.

Tip

To hide an app you’ve bought so it no longer appears in Purchased, right-click its icon and choose Hide Purchase. (To unhide it later, click the Account link on the main page of the App Store; under the “iTunes in the Cloud” heading, choose View Hidden Purchases.)

And speaking of updates: Since Apple knows what programs you have, it can let you know when new versions are available. And it does: A numbered badge appears next to the ![]() → App Store command. The updates are small files, so they download quickly; the App Store delivers only the pieces that have actually changed.

→ App Store command. The updates are small files, so they download quickly; the App Store delivers only the pieces that have actually changed.

Some details:

You can opt to have new versions of your programs quietly and automatically downloaded and installed in the background, so you’re never bugged about their arrival. (Open System Preferences→App Store. “Download newly available updates in the background” downloads new versions but asks your permission before installing them. “Install app updates” goes the next step and installs them without consulting you further.)

“Automatically download apps purchased on other Macs” (also in System Preferences→App Store) ensures that when you download an app on one Mac, it auto-downloads on all your other ones, too (assuming they’re logged in with the same iCloud account). Handy, really.

If the App Store app indicates that new versions of your programs are available, then click the pop-up menu next to the Update All button. There, for your time-shifting pleasure, is a shortcut menu containing options like Install Now, Try in an Hour, Try Tonight, and Remind Me Tomorrow. The point is to set up a downloading session for a time when (a) you’re in a Wi-Fi hotspot or (b) you’re asleep and those big downloads won’t slow down anybody’s Internet work.

One final advantage of the App Store concept: If you decide to use Launchpad, described starting in “Launchpad”, then anything you’ve bought from the App Store is easy to delete with a single click.

In general, the App Store works exactly like the iPhone/iPad App Store. Click a program’s icon to open its details page. Here you’ll find reviews and ratings from other people, a description, pictures (screenshots) of the program, and much more information to help you make a good buying decision. See Figure 6-1 for more details.

When you buy an app, Launchpad opens automatically, so you can see where it went.

Other Ways to Get Mac Software

In general, new programs arrive on your Mac via one of two avenues: as a download (whether from the App Store or not) or, rarely, on a CD or DVD.

Downloading Compressed Files

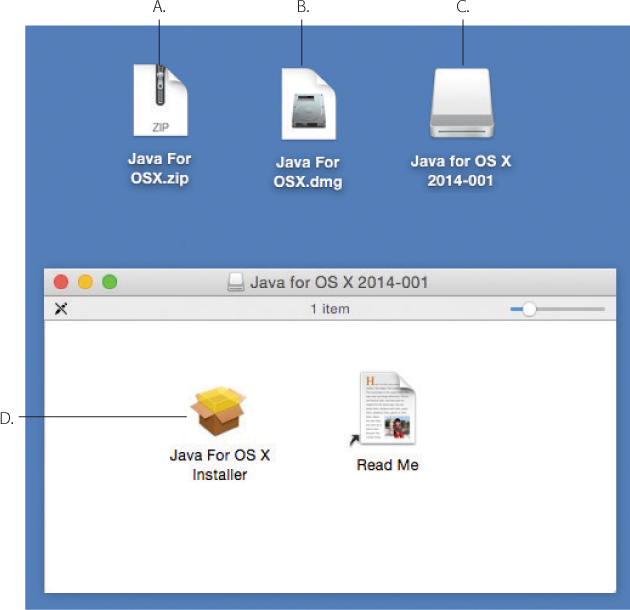

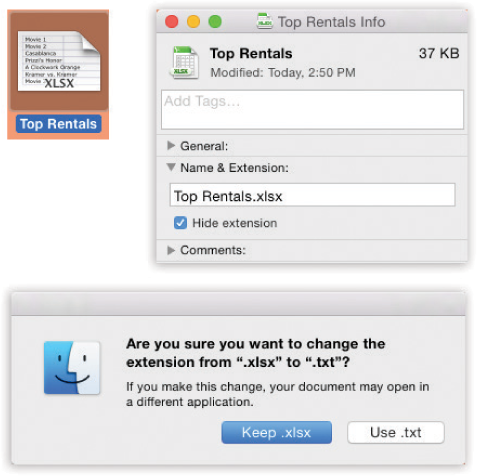

Programs you download from the web (not the App Store) generally arrive in a specially encoded, compressed form (Figure 6-2). And unless you’ve changed the settings, they arrive in the Downloads folder on your Dock.

The downloaded file’s name usually has a file name extension like .zip (the standard compression file format for Windows and Mac files) or .dmg (a disk image file, described below).

You may occasionally run into .tar files (tape archive, an ancient Unix utility), .gz (gzip, a standard Unix compression format), or combo formats like .tar.gz or .tgz.

Fortunately, you generally don’t have to worry about any of this; most web browsers, including Safari, automatically unzip and unstuff downloads of all types.

Figure 6-2. A: This is the downloaded compressed file. Double-click to get…

B: The .dmg (disk image) file. Double-click it to “mount” the disk image.

C: And now, the disk image itself. Double-click to open the installer window. (Dismiss the warning that the software came from the Internet.) “Eject” it after the installation is complete.

D: Here’s the actual installer.

After the installation, you can delete all this stuff (except maybe the .dmg file, if you think you might want to install the software again later).

Disk images (.dmg files)

Once you’ve downloaded a program, it often takes the form of a disk image file, whose name ends with the letters .dmg (middle top in Figure 6-2).

Disk images are common in macOS. All you have to do is double-click the .dmg icon. After a moment, it magically turns into a disk icon on your desktop, which you can work with just as though it were a real disk (top right in Figure 6-2). For example:

Double-click it to open it. The software you downloaded is inside.

Remove it from your desktop by dragging it to the Trash (whose icon turns into a big silver

key as you drag), selecting it and pressing

key as you drag), selecting it and pressing  -E (the shortcut for File→Eject), clicking its

-E (the shortcut for File→Eject), clicking its  button in the Sidebar, or right-clicking or two-finger clicking it and then choosing Eject from the shortcut menu.

button in the Sidebar, or right-clicking or two-finger clicking it and then choosing Eject from the shortcut menu.You’ve still got the original .dmg file you downloaded, so you’re not really saying goodbye to the disk image forever.

When you’ve finished unzipping or unstuffing a downloaded file, you may have several icons on your desktop or in the Downloads folder. It’s generally safe to throw them away—the .sit, .tar, .gz, or .tgz file you originally downloaded, for example, or the .dmg icon.

The disk image icon, the one that contains the actual software or its installer (top right in Figure 6-2), is a phantom drive, held in memory, that will go away by itself when you log out. So after installing its software, feel free to drag it to the Trash (or select it and press ![]() -E to “eject” it).

-E to “eject” it).

Performing the installation

Once you’ve got a disk icon on your desktop—either a pseudo-disk from a disk image or a CD or DVD you’ve inserted—you’re ready to install the software. You can install many macOS programs just by dragging their icons or folders to your hard drive (usually the Applications folder). Others offer a traditional installer program that requires you to double-click, read and accept a license agreement, and so on.

Uninstalling Software

If you got a program from the App Store, it’s easy to delete from the Launchpad (“Launchpad”).

If you got it from some other source, well, there’s generally no Uninstall program. To uninstall a program, you just drag it (or its folder) to the Trash.

Some programs leave harmless scraps of themselves behind; to check for them, look for preference files or folders bearing the dearly departed program’s name in your Library folders (especially in Application Support) and in your Home→Library→Preferences folder.

Opening macOS Programs

You can launch (open) an application in any of several ways:

Single-click an icon on the Launchpad, described on the following pages.

Single-click a program’s icon on the Dock, the Sidebar, or the Finder toolbar.

Use Spotlight. Hit

-space bar, type the first letters of the program’s name, and then press Return.

-space bar, type the first letters of the program’s name, and then press Return.Double-click an app’s icon in the Finder.

If you’ve added the Applications folder to your Dock, then click the Dock icon to open the pop-up fan, grid, or list of icons. Then click the program you want (or even type the first few letters of its name and then press Return).

Select an application icon and then press

-O (short for File→Open) or

-O (short for File→Open) or  -

- .

.Use the submenus of the

menu’s Recent Items→Applications command.

menu’s Recent Items→Applications command.

Tip

Once you’ve opened the Recent Items→Applications submenu, you can hold down the ![]() key to witness a startling sight: All the program names (Preview, Photoshop, and so on) change to say “Show Preview in Finder,” “Show Photoshop in Finder,” and so on. The Recent Items command, in other words, now gives you a direct way to jump to the icon of a program you might want to open, huddling in Applications or whatever window it’s in.

key to witness a startling sight: All the program names (Preview, Photoshop, and so on) change to say “Show Preview in Finder,” “Show Photoshop in Finder,” and so on. The Recent Items command, in other words, now gives you a direct way to jump to the icon of a program you might want to open, huddling in Applications or whatever window it’s in.

Open a document icon in any of these ways, or drag a document onto the icon of a program that can open it (whether in the Dock, the Finder toolbar, the Sidebar, or a folder window).

Tip

If you press Option as you open an application (or anything else) in the Finder, you automatically close the window that contains its icon. Later, when you return to the Finder, you find a neat, clean desktop—no loitering windows.

Launchpad

The Launchpad app presents a dark background with evenly spaced icons that represent all your programs (Figure 6-3). You can open one with a single click.

Why did Apple feel the need to create yet another way to open programs?

First, because Launchpad fits right into the general theme of making the Mac look and work more like the iPad. Launchpad is a dead ringer for the Home screens of an iPad, iPhone, or iPod Touch.

Second, it’s a much less intimidating place for technophobes to learn to love than, say, the Applications folder.

And, third, it’s a lot quicker to get to than the Applications folder. You can summon it instantly, using any of these methods:

Put four fingers on your trackpad and pinch them together. The Launchpad appears instantly, no matter what program you were in; you don’t have to duck back into the Finder, navigate to the Applications folder, and so on.

Press the Launchpad key. Recent Macs have a special Launchpad icon painted right on the F4 key (

).

).Click its icon on the Dock. It’s the one resembling a rocket (

).

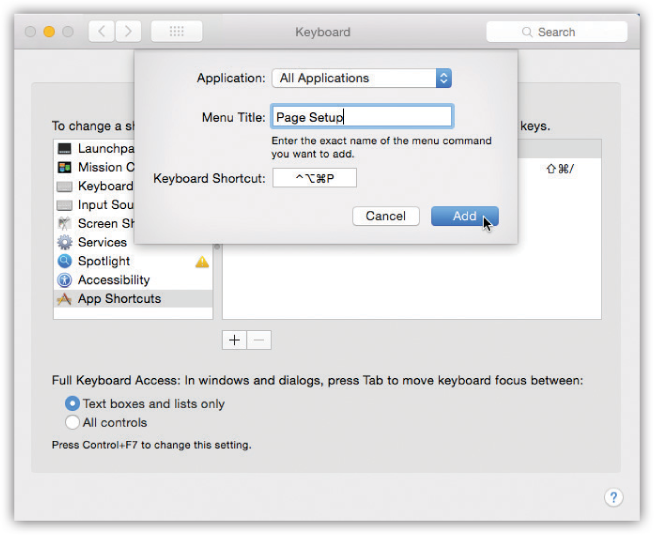

).Press a keyboard shortcut of your choice. To set that up, choose

→ System Preferences→Keyboard. Click the Shortcuts tab, and then click Launchpad & Dock in the left-side list. On the right, make sure Show Launchpad is turned on—and then double-click in the blank space to the right of it and press the key combination you want.

→ System Preferences→Keyboard. Click the Shortcuts tab, and then click Launchpad & Dock in the left-side list. On the right, make sure Show Launchpad is turned on—and then double-click in the blank space to the right of it and press the key combination you want.Move the cursor into one of the screen’s four corners. To set up these options, open

→ System Preferences→Mission Control. Click Hot Corners to choose a corner of the screen for Launchpad.

→ System Preferences→Mission Control. Click Hot Corners to choose a corner of the screen for Launchpad.Open it as you would any other program. It’s in your Applications folder.

Figure 6-3. You can open Launchpad by clicking its Dock icon or by using a four-finger pinching gesture on your trackpad. Launchpad covers your entire main monitor, hiding everything else.

Use the arrow keys to navigate a page; press  -arrow to move between pages; press Option to make the icons start wiggling, ready for deletion.

-arrow to move between pages; press Option to make the icons start wiggling, ready for deletion.

One thing’s for sure: Sooner or later, you’ll wind up in Launchpad. Only three visual elements appear there:

Icons. Each icon represents one of your programs. Apple’s programs are listed first, in alphabetical order: App Store, Automator, Calculator, and so on. Then come all your other programs, again in A-to-Z order. Click one to open that program.

Sparkly animated twinkles surround any new app you’ve installed. (You can see them at bottom in Figure 6-3.)

Note

The only program icon that doesn’t appear in Launchpad…is Launchpad’s. That’s a good thing. You wouldn’t want to wind up in an infinite loop.

Search box. This box at the top of the screen lets you pluck one needle from your haystack of apps, no matter what page it’s on. You don’t have to click there first—just start typing when Launchpad is before you. With each letter you type, Launchpad hides everything but the matching app icons.

Home-page dots. As you install more and more programs, Launchpad makes room for them by creating additional screens. You can spread your new programs’ icons across an unlimited number of launch screens.

The little white dots are your map. Each represents one Launchpad screen. If the third one is “lit up,” then you’re on the third screen.

To move among the screens, press

-arrow keys, or swipe horizontally with two fingers on the trackpad (Magic Mouse: one finger). Or tap directly on one of the little dots to jump to the corresponding screen.

-arrow keys, or swipe horizontally with two fingers on the trackpad (Magic Mouse: one finger). Or tap directly on one of the little dots to jump to the corresponding screen.

Tip

To exit Launchpad without opening anything, click a blank spot, tap the Esc key, or—most fun of all—spread the same four fingers on the trackpad.

Redesigning the Launchpad Screens

If you use Launchpad a lot, it’s worth taking a moment to arrange its icons into logical categories or a sensible sequence. As it turns out, you can freely drag them into new spots; the other icons scoot aside to make room.

Tip

You can even drag an icon directly to the Dock to install it there for quicker access.

You can create additional screens, too. To do that, drag an icon to the right edge of the screen; keep your mouse button down. The first screen slides off to the left, leaving you on a new, blank one where you can deposit the icon.

You can organize your icons on these Home pages by category, frequency of use, color, or whatever tickles your fancy.

Folders

The Launchpad just wouldn’t be like the iPad if it didn’t also let you organize your apps into folders. Folders let you organize your apps, de-emphasize the ones you don’t use often, and restore order to that horribly flat, multipage display of icons.

To create a folder, drag one app’s icon on top of another. MacOS puts both of them into a single new folder (Figure 6-4). If they’re the same kind of app, it even tries to figure out what category they both belong to—and names the new folder accordingly (“Music,” “Photos,” “Games,” or whatever). This new name is only a proposal; an editing window also appears so that you can type a custom name that you prefer.

Figure 6-4. Open a folder by clicking once, or by pressing  -

- . A panel sprouts from the folder icon, revealing its contents; the rest of the screen goes away. Now you can drag the icons around inside it. You can also edit the folder’s name (click it first).

. A panel sprouts from the folder icon, revealing its contents; the rest of the screen goes away. Now you can drag the icons around inside it. You can also edit the folder’s name (click it first).

A folder can hold several rows’ worth of icons; if you add more apps than that, Launchpad adds additional “pages” that you scroll horizontally. (Little white dots indicate which page you’re on.)

Take an app out of a folder by dragging its icon anywhere else on the screen. The other icons scoot aside to make room. If you remove all but one app from a folder, the folder disappears.

Move a folder around by dragging, as you would any other icon.

Deleting App Store Programs

If you’ve downloaded some apps from the App Store, you’ll find a bonus feature here in Launchpad: They’re especially fun to delete.

Start by holding the mouse down on any icon until, after about a second, all the icons begin to—what’s the correct term?—wiggle. (If you have an iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch, this should look familiar.)

Tip

You can also just press the Option key to trigger the wiggling. Sometimes, every second counts.

At this point, you may notice that some of them have sprouted little red ![]() ’s. Those are the ones you downloaded from the App Store.

’s. Those are the ones you downloaded from the App Store.

To delete an App Store program you don’t need anymore, click that ![]() to make it say bye-bye—instantly and for good. It doesn’t even have a layover in the Trash.

to make it say bye-bye—instantly and for good. It doesn’t even have a layover in the Trash.

Note

You can’t delete non–App Store apps this way, so no ![]() appears on those icons. Why not? Because this deletion method is so fast and permanent. It’s not much of a risk for App Store apps, because you can always download them again—but that would not be true of other apps.

appears on those icons. Why not? Because this deletion method is so fast and permanent. It’s not much of a risk for App Store apps, because you can always download them again—but that would not be true of other apps.

Windows That Auto-Reopen

For decades, opening a program on the Mac presented exactly the same thing every time: a blank screen, or maybe a welcome screen. It was up to you to specify what document you then wanted to work on.

Now, though, whatever documents were open when you last quit that program magically reopen, ready for you to get back to work. Everything is exactly as it was, including your window and palette positions. Incredibly, any text that was highlighted when you last quit the program is still highlighted, and the insertion point is just where you left it.

This is all handy if you tend to work on the same documents day after day; the auto-reopened document serves as a refresher on what you were in the middle of doing. You can skip fussing with the Open command, remembering what you were doing, rearranging the windows the way you like them, and so on.

Then again, maybe you can’t stand this feature.

Fortunately, it’s easy to turn it off, either globally, on a per-program basis, or on a per-Quit basis:

Turn off auto-reopen for good. Open System Preferences→General, and click “Close windows when quitting an app.”

Prevent your current setup from being memorized. You can also prevent just one particular program from reopening its documents the next time—at the time you’re quitting it. To do that, press Option while you quit the program (for example, when you choose Safari→Quit or press

-Q). The Quit command magically changes to Quit and Close All Windows. The next time you open the program, it will have forgotten all about your window setup.

-Q). The Quit command magically changes to Quit and Close All Windows. The next time you open the program, it will have forgotten all about your window setup.(On the other hand, if you’ve turned off the “Restore windows” feature in System Preferences, then pressing the Option key makes the Quit command say Quit and Keep Windows.)

Make a program forget its window setup as you reopen it. If it’s too late for the tip in the previous paragraph, you can force a program to start up in its empty, virginal state by pressing the Shift key as it opens. That forces the program to forget the previous window setup.

Turn off auto-open for one program. Suppose you like the auto-window-reopening feature in most programs. But there’s one particular program that you never want to memorize your window setup—maybe for security reasons, or maybe because you use that app for something different every day.

Before long, some shareware program will crop up to make that easy. For now, though, you can do the job manually. It’s a quick, one-time step, but it does involve mucking around with one of the Mac’s invisible folders. See the box below.

The “Heads-Up” Program Switcher

Only one program can be in front, or active, at a time.

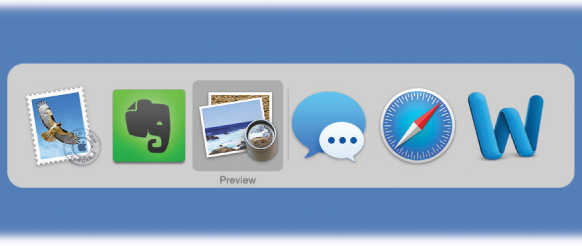

To switch to a different program, you could click or double-click its icon (in the Dock, the Applications folder, Launchpad, or wherever). But the fastest method is often to use the ![]() -Tab keystroke (Figure 6-7).

-Tab keystroke (Figure 6-7).

You can use this feature in three different ways, which are well worth learning:

If you keep the

key pressed, then each press of the Tab key highlights the Dock icon of another program, in left-to-right Dock order. Release both keys when you reach the one you want. MacOS brings the corresponding program to the front. (To move backward through the open programs, press Shift-

key pressed, then each press of the Tab key highlights the Dock icon of another program, in left-to-right Dock order. Release both keys when you reach the one you want. MacOS brings the corresponding program to the front. (To move backward through the open programs, press Shift- -Tab.)

-Tab.)If you leave the

key pressed, you can choose a program by clicking its icon with your mouse or by pressing the

key pressed, you can choose a program by clicking its icon with your mouse or by pressing the  or

or  keys.

keys.A single press of

-Tab takes you to the program you used most recently, and another, separate

-Tab takes you to the program you used most recently, and another, separate  -Tab bounces back to the program you started in.

-Tab bounces back to the program you started in.Imagine, for example, that you’re doing a lot of switching between two programs, like your web browser and your email program. If you have five other programs open, you don’t want to waste your time

-tabbing your way through all the open programs just to get back to your web browser.

-tabbing your way through all the open programs just to get back to your web browser.

Tip

Here’s a related keystroke, equally awesome. If you press ![]() -~ (the tilde key next to the number 1), you switch to the next window in the same program.

-~ (the tilde key next to the number 1), you switch to the next window in the same program.

Figure 6-7. Apple calls this row of open program icons a “heads-up display,” named after the projected data screen on a Navy jet windshield that lets pilots avoid having to look down at their instruments.

Full Screen Mode

Features are great and all. But the more of them your software accumulates, the more toolbars and icon panels fill the screen, and the bigger the clutter problem becomes. After a while, all that “chrome” (as software designers call it) winds up crowding out the document you’re actually trying to work on.

That’s why Apple invented Full Screen mode. It’s not available in all programs, but it’s showing up in more and more of them—including almost all Apple programs: App Store, Calendar, Chess, Final Cut Pro, Font Book, GarageBand, iBooks, iMovie, iTunes, Keynote, Mail, Maps, Messages, Notes, Photo Booth, Photos, Preview, Safari, and so on.

To take a program into Full Screen mode, click the Full Screen button: the round, green dot in the upper-left corner of the document window. (And how do you know if your program even offers Full Screen mode? As your cursor approaches the green dot button, a tiny double-arrow logo appears inside: ![]() . If it’s a

. If it’s a ![]() instead, then the app isn’t eligible for Full Screening.)

instead, then the app isn’t eligible for Full Screening.)

When you click the green ![]() , the Mac hides the menu bar, scroll bars, Dock, status bars, and any other bars or palettes surrounding your work area. The window’s edges expand all the way to the edges of the screen (Figure 6-8, bottom).

, the Mac hides the menu bar, scroll bars, Dock, status bars, and any other bars or palettes surrounding your work area. The window’s edges expand all the way to the edges of the screen (Figure 6-8, bottom).

Tip

You may as well learn the keyboard shortcut to enter Full Screen mode: Control-![]() -F. The same keystroke leaves Full Screen mode, but you can also tap the Esc key for that purpose.

-F. The same keystroke leaves Full Screen mode, but you can also tap the Esc key for that purpose.

The menu bar is available—it’s just hidden. Move the pointer to the top of the screen to make it reappear.

To exit Full Screen mode, make the menu bar appear, and then click that green dot in the upper-left corner of the window (which now looks like this: ![]() ).

).

Figure 6-8. Top: So much for the glorious web. You’re seeing a web page segment, swimming in an ocean of toolbars, scroll bars, status bars, menu bars, and distracting desktop.

Bottom: In Full Screen mode, Safari stretches to the very edges of your screen, and everything else disappears. (Your address bar and tab bars are still available in this case.)

Each full-screen app becomes its own desktop in Mission Control. And you can put a full-screen app on each of your monitors, too.

To leave Full Screen mode, move your cursor to the top of the screen so that the menu bar reappears. Click the green dot once again (top left of your document window).

Split Screen Mode

Once Apple gave us Full Screen mode, the next step was obvious: split Full Screen mode. In this arrangement, two windows fill the screen, edge to edge and top to bottom. Just as in Full Screen mode, the menu bar, Dock, and all other cluttery extras are hidden to maximize screen space; the only difference is that two apps are now sharing that big monitor canvas.

This combination works very well when you want to keep a continuously updating app visible—Twitter, Mail, or FaceTime, for example—while continuing to do work in a second app. It’s also handy when you’re referring to one app (a recipe in your web browser) and making notes in another (an ingredients list in Notes).

Once again, though, Split Screen doesn’t work in all apps—only the ones that work in Full Screen mode.

Starting Split Screen Mode, Method 1

There are two ways to get in and out of Split Screen mode, but this one is quickest:

Click-and-hold the green

button at the top-left corner of Window #1. (See Figure 6-9, top.)

button at the top-left corner of Window #1. (See Figure 6-9, top.)The weirdest thing now happens: Whichever half of your monitor contains this window (usually the left side) becomes shaded blue (Figure 6-9, second from top). That’s the Mac’s way of telling you: “When you release your mouse or trackpad, this window will snap to fill only this half of the screen.”

Tip

At this point, you could, if you liked, drag the window to the opposite side of the screen—still holding down the mouse or trackpad—to make it fill that half.

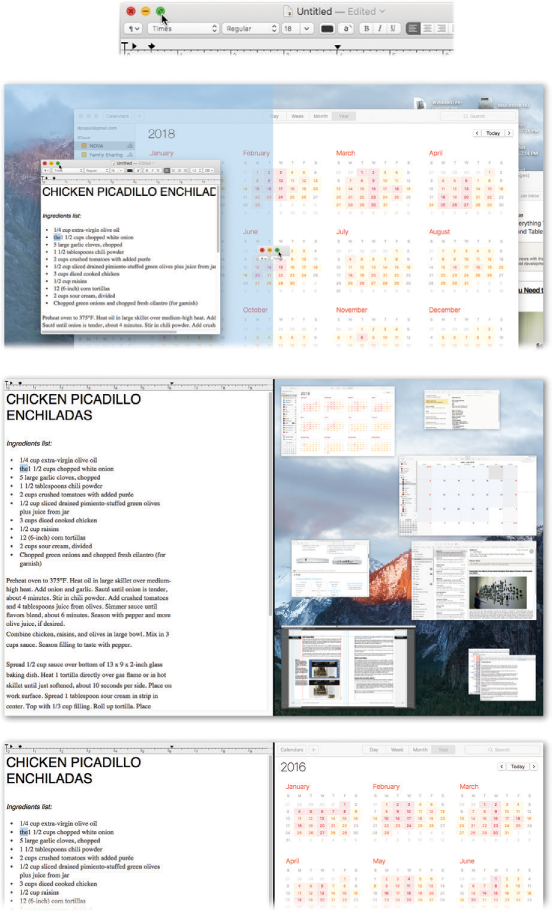

Figure 6-9. Here’s the complete tutorial for turning on Split Screen mode.

Top: Hold down the green button in the first app.

button in the first app.

Second from top: That half of your screen gets a blue tint.

Third from top: Release the mouse; that window now fills half your entire screen. Meanwhile, all other open windows appear in miniature so that you can choose the one you want to fill the other half of your screen. (There may even be a little pile of additional window cards at the bottom corner. These are apps whose software companies have been too lazy to make them compatible with the Full Screen/Split Screen feature.)

Bottom: And voilà: Two apps, perfectly splitting your screen’s full height and width. Feel free to drag the divider line sideways to adjust the proportions.Release the mouse or trackpad.

And sure enough: Window #1 now fills exactly half the screen (Figure 6-9, third from top). Meanwhile, all other open windows shrink down into miniature cards. That’s the Mac’s way of telling you: “Please choose Window #2, the one you’d like to fill the rest of the screen.”

Click the miniature window you want to fill the remaining half of the screen.

Now you’ve got two windows sharing your screen space 50-50 (Figure 6-9, bottom).

If you like, you can now grab the divider line and drag it, thereby adjusting the proportion of the screen occupied by each app.

Figure 6-10. Drag a window onto an existing Full Screen–mode window’s thumbnail. The + shows you which side of the screen this new window will occupy in Split Screen mode. Release the mouse, and then click the split thumbnail to make it fill your screen.

Starting Split Screen Mode, Method 2

The second method makes sense only after you’ve read about Mission Control and Spaces, starting on the next page. Bookmark this spot, go read that, and then return here.

Back so soon? OK, great!

Now that you know what the Spaces bar is, here’s the tip: You can drag a second window onto an existing full-screen app’s thumbnail in the Spaces bar; see Figure 6-10 for details.

Exiting Split Screen Mode

Just as there are two ways to enter Split Screen mode, there are also two ways to exit it.

The title-bar method. Move your cursor to the top edge of either window and pause; its title bar appears. Now click the green

button.

button.That window becomes a normal floating window. (The other window remains in Full Screen mode, on its own desktop; you can switch to it as described in “Switching Spaces”.)

Mission Control method. Enter Mission Control, as described next. (For example, press the

key on your keyboard.) Move your cursor to the top of the screen to make the Spaces bar expand. Point to the desktop icon that contains the split screen; click the

key on your keyboard.) Move your cursor to the top of the screen to make the Spaces bar expand. Point to the desktop icon that contains the split screen; click the  in the top left.

in the top left.In this case, both windows exit Full Screen and become floating windows again.

Mission Control: Death to Window Clutter

These days, managing all the open windows in all the open programs can be like herding cats. Off you go, burrowing through the microscopic pop-up menus of your Dock, trying to find the window you want. And heaven help you if you need to duck back to the desktop—to find a newly downloaded file, for example, or to eject a disk. You have to fight your way through 50,000 other windows on the way to the bottom of the “deck.”

Mission Control tackles this problem in a fresh way. The concept is delicious: With one mouse click, keystroke, or finger gesture, you shrink all windows in all programs to a size that fits on the screen (Figure 6-11), like index cards on a bulletin board. Now you feel like an air-traffic controller, with all your screens arrayed before you. You click the window you want, and you’re there. It’s efficient, animated, and a lot of fun.

Tip

If you use Mission Control a lot, the zooming animation might get a little tiresome. Fortunately, you can turn that off. Open System Preferences→Accessibility→Display, and turn on Reduce Motion. From now on, Mission Control simply pops to the screen instead of zooming.

The window miniatures are scattered all over your screen. The placement isn’t entirely random; macOS tries to place the thumbnails on the screen relative to their full-size windows’ positions, relative to the top, bottom, and sides of your monitor.

You can impose a little more order on all of this, though. Open System Preferences→Mission Control, and turn on “Group windows by application.” The windows still don’t overlap, but at least the windows of each program are laid out near one another in Mission Control.

Starting and Stopping Mission Control

Mission Control is a program, just like any other. So you can open it with a click on its Dock icon, from Launchpad, from the Applications folder, and so on.

But it’s really meant to be opened quickly, fluidly, naturally, whenever the mood seizes you—with a gesture. On the trackpad, that’s a swipe upward with three fingers. (On the Magic Mouse, it’s a double-tap with two fingers—taps, not clicks.)

Note

You can change this gesture so that it requires four fingers, if you like, in System Preferences→Trackpad (or Mouse)→More Gestures→Mission Control. Use the pop-up menu.

Or you can press the dedicated ![]() key (formerly the Exposé key), if you have one, on the top row of your keyboard.

key (formerly the Exposé key), if you have one, on the top row of your keyboard.

Or you can press Control-![]() .

.

And even that’s just the beginning of the ways you can open Mission Control; read on.

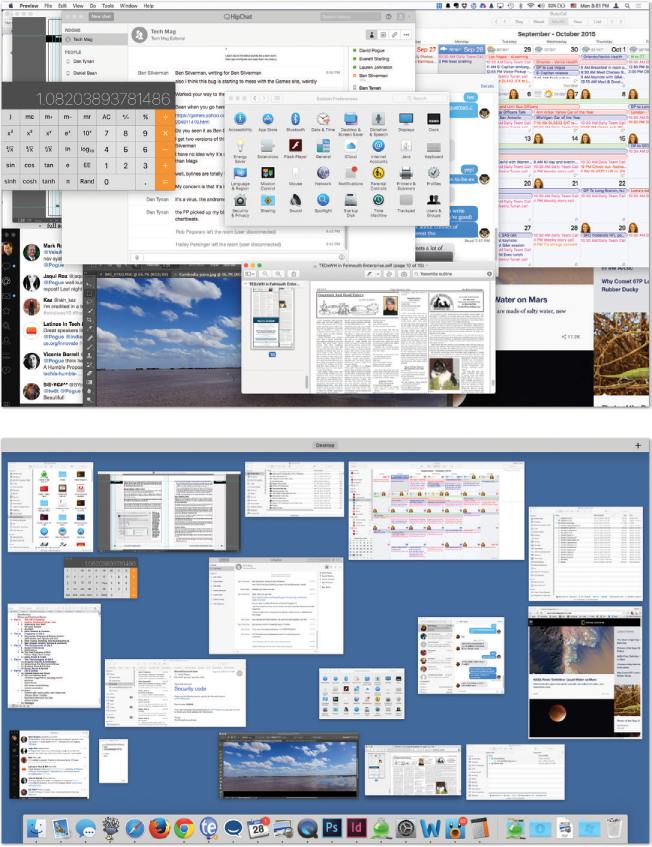

Figure 6-11. Top: Quick! Where’s the Finder in all this mess?

Bottom: With a three- or four-finger upward swipe on the trackpad, you can open Mission Control and spot every window, shrunken but not overlapped. These aren’t static snapshots of the windows at the moment you Mission Controlled them. They’re live, still-updating windows, as you’ll discover if one of them contains a QuickTime movie or a web page that’s still loading.

Note

To exit Mission Control without clicking any of your windows or virtual screens, swipe down with three fingers. Or tap the Esc key. Or click a spot in the empty background.

Mission Control keystrokes

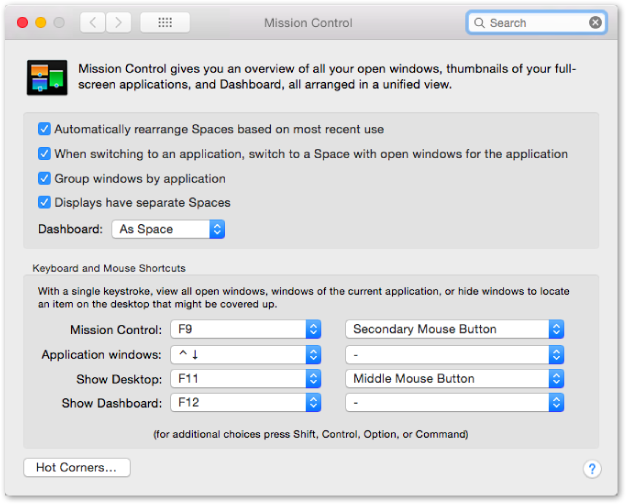

You can reassign the Mission Control functions to a huge range of other keys, with or without modifiers like Shift, Control, and Option. To view your options, choose ![]() → System Preferences and then click the Mission Control icon.

→ System Preferences and then click the Mission Control icon.

Here you’ll find four pop-up menus (Figure 6-12). The first, Mission Control, lets you specify how you want to open Mission Control. The other three—Application windows, Show Desktop, and Show Dashboard—correspond to the three functions of the older Exposé and Dashboard features, described later in this chapter.

Figure 6-12. You can trigger Mission Control in any of five ways: by clicking its icon, with a finger gesture, by twitching your cursor into a certain corner of the screen (Hot Corners), by pressing a key (bottom half of this box), or by clicking the extra buttons on a multibutton mouse, including the Apple Mouse. Of course, there’s nothing to stop you from setting up all of these ways, so you can press or swipe in some situations and twitch or click in others.

Within each pop-up menu, for example, you’ll discover that all your F-keys—F1, F2, F3, and so on—are available as triggers. If, while the pop-up menu is open, you press one or more of your modifier keys (Shift, Option, Control, or ![]() ), then all these F-key choices change to reflect the key you’re pressing; now the pop-up menu says Shift-F1, Shift-F2, Shift-F3, and so on. That’s how you can make Shift-F1 trigger Mission Control, for example.

), then all these F-key choices change to reflect the key you’re pressing; now the pop-up menu says Shift-F1, Shift-F2, Shift-F3, and so on. That’s how you can make Shift-F1 trigger Mission Control, for example.

These pop-up menus also contain choices like Left Shift, which refers to the Shift key on the left side of your keyboard. That is, instead of pressing F9 to open Mission Control, you could simply tap the Shift key.

Note

This is only an example. Repeat: This is only an example. Actually using the Shift key to open Mission Control is a terrible, terrible idea, as you’ll quickly discover the next time you try to type a capital letter. This feature is intended exclusively for hunt-and-peck typists who never use the Shift key on one side.

If you have a laptop, you’ll also find out that you can tap the fn key alone for Mission Control—and this time, it’s a great choice, because fn otherwise has very little direction in life.

If your mouse has more than one button, you’ll see a second column of pop-up menus in System Preferences (Figure 6-12). Each pop-up menu offers choices like Right Mouse Button and Middle Mouse Button. Use these pop-up menus to assign Mission Control (or Exposé or Dashboard) to the various clickers on your mouse: Right-click to hide all windows, middle-click to reveal the desktop, and so on.

Note, by the way, that on a laptop, the wording isn’t “right mouse button”—it’s “secondary mouse button.” Which means “right-click.” Which means that on a laptop, you can set it up so that a “right-click” trackpad gesture triggers one of these functions. See “Notes on Right-Clicking” for all the different ways you can trigger a right-click.

Screen corners

If you click Hot Corners, you see something like Figure 10-13 (“Activating the screen saver”). The four corners here represent the corners of your screen. Using these menus, you can assign a window-management feature to each corner; for example, if you choose Mission Control from the first pop-up menu, then when your pointer hits the upper-left corner of the screen, you’ll open Mission Control. (Launchpad and Notification Center are options here, too.)

Depending on the size of your screen, this option can feel awkward at first. But if you’ve run out of keystrokes that aren’t assigned to other functions, be glad that Apple offers you this alternative.

Note

In previous versions of the operating system, whipping the pointer into a corner was one good way to turn on your screen saver. Apple hasn’t forgotten about that, which is why you’ll also find commands called Start Screen Saver and Disable Screen Saver in the pop-up menus. Apple wants to make sure you don’t get confused and assign two different functions to the same corner.

Managing Windows in Mission Control

Once you open Mission Control, you can click any window’s thumbnail to open it.

Tip

Try holding down the Shift key as you do it. You’ll enjoy watching all your windows shift around with macOS’s patented slow-motion animation, which can be quite a sight.

Or, if you decide to abandon ship and return to whatever you were doing, swipe downward with three fingers on the trackpad (two on the Magic Mouse), or press the Esc key.

The trouble with miniaturized windows is that, well, they’re miniaturized. The more windows you have open, the smaller they are, and the harder it is to see what’s in them.

If you need a little help identifying a window miniature, you have three options:

Point to a window thumbnail without clicking. MacOS displays a label for that window.

If that’s not enough information, press the space bar. That, of course, is the Quick Look keystroke, and it works here, too. It magnifies the window you’re pointing to, making it full size—big enough for you to read its contents and identify it.

Press

-~. That keystroke takes you into Exposé, described later in this chapter.

-~. That keystroke takes you into Exposé, described later in this chapter.

Spaces (Virtual Desktops)

Mission Control’s other star feature, Spaces, gives you up to 16 full-size monitors. Ordinarily, of course, attaching so many screens to a single computer would be a massively expensive proposition, not to mention detrimental to your living space and personal relationships.

Fortunately, Spaces monitors are virtual. They exist only in the Mac’s little head. You see only one at a time; you switch using Mission Control or a gesture.

But just because the Spaces screens are simulated doesn’t mean they’re not useful. You can dedicate each one to a different program or kind of program. Screen 1 might contain your email and chat windows, arranged just the way you like them. Screen 2 can hold Photoshop, with an open document and the palettes carefully arrayed. On Screen 3: your web browser in Full Screen mode.

You can also have the same program running on multiple screens—but with different documents or projects open on each one.

These desktops are also essential to macOS’s full-screen apps feature, because each full-screen app gets its own Spaces desktop.

Now, virtual screens aren’t a new idea—this sort of software has been available for years. But the Mac was the first to make it a standard feature of a consumer operating system.

It’s still what most people would consider an advanced feature, and it’s definitely confusing at first. But it’ll be here when you’re ready for it.

Creating a Desktop

Mission Control generally starts you off with just one Space (or “desktop,” as it’s labeled)—the one you’ve been using all along. If you’ve clicked the ![]() button in an app to make it full screen, it fills an additional desktop unto itself.

button in an app to make it full screen, it fills an additional desktop unto itself.

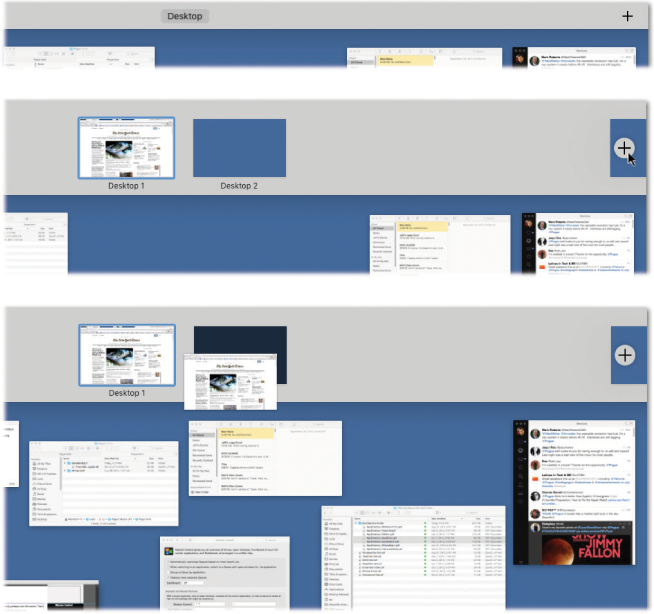

To create another desktop, enter Mission Control. At the top edge of the screen, the gray strip—the Spaces bar—is the command center for creating, deleting, rearranging, and configuring your virtual desktops.

Note

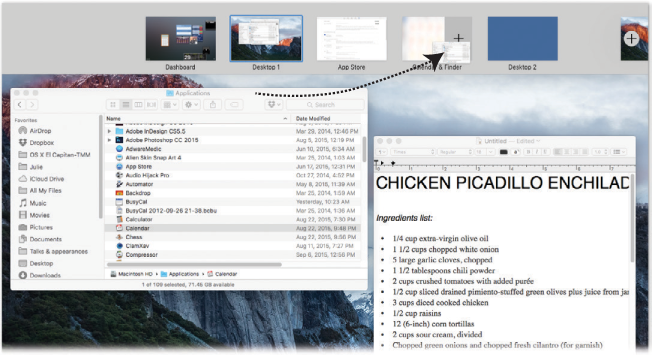

To save space, the Spaces bar starts out as a very thin strip bearing only the names of your desktops (Figure 6-13, top). Move your cursor into this strip to expand it vertically, so you can now see the actual thumbnail images of your desktops (Figure 6-13, bottom).

Figure 6-13. Top: When you enter Mission Control, the Spaces bar is thin and collapsed.

Middle: Click the  button to create a new blank desktop, numbered sequentially.

button to create a new blank desktop, numbered sequentially.

Bottom: Drag one of the window miniatures onto this new desktop. Or several.

Once you’re in Mission Control, you can proceed in either of two ways:

The long way. See Figure 6-13 for the step-by-steps of clicking the + button in the upper-right corner.

Note

If you’ve positioned your Dock against the right side of the screen, then the + button appears when you point to the upper-left corner. And to create a new screen by dragging a window’s icon (see “The short way,” next), drag to the upper-left corner of the screen.

The short way. Drag one window thumbnail onto any blank spot on the Spaces bar. The Mac creates a new desktop to hold it.

Switching Spaces

Once you’ve got Spaces set up and turned on, the fun begins. Start by moving to the virtual screen you want; it’s like changing the channel. Here are some ways to do that:

Swipe horizontally on your trackpad with three fingers. (On the Magic Mouse, it’s two fingers.) If you have a trackpad or a Magic Mouse, this is definitely the method to learn; it’s fast, fluid, and happy.

You can change this gesture so that it requires an additional finger, if you like, in System Preferences→Trackpad (or Mouse)→More Gestures.

Tip

If you perform this swipe slowly, you can drag the next Space only partway onto the screen. That’s sometimes handy when you want to get your bearings or to just peek into the next screen.

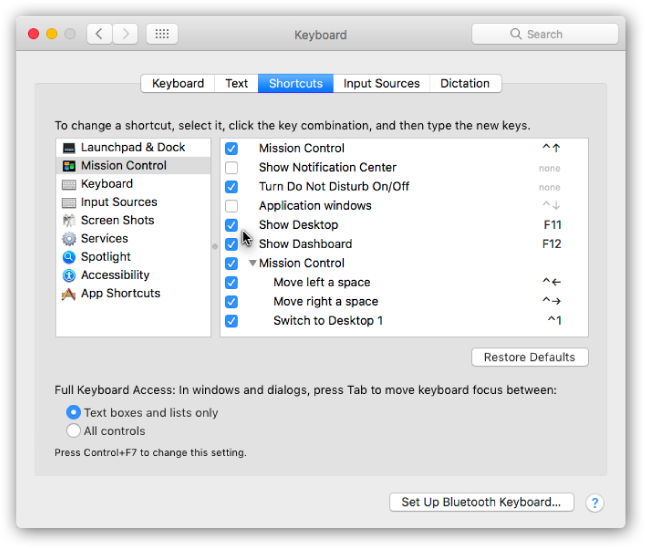

While pressing the Control key, type the number of the desktop you want. For example, hit Control-3 to jump to your third screen. (You have to turn on this feature first, though. See Figure 6-14.)

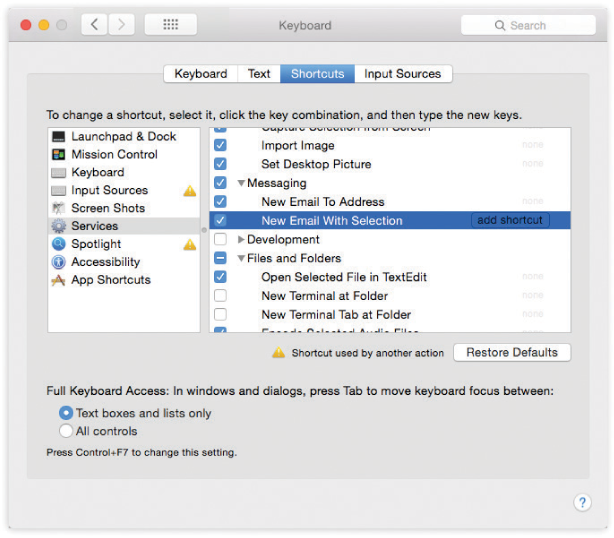

Figure 6-14. To control Spaces from the keyboard, open

→ System Preferences→Keyboard. Click Keyboard Shortcuts and then Mission Control. As shown here, Apple has preassigned keyboard shortcuts to your various Spaces—but they’re not turned on yet. Turn on the checkboxes for the shortcuts you want. (You can change those shortcuts here, too.)

→ System Preferences→Keyboard. Click Keyboard Shortcuts and then Mission Control. As shown here, Apple has preassigned keyboard shortcuts to your various Spaces—but they’re not turned on yet. Turn on the checkboxes for the shortcuts you want. (You can change those shortcuts here, too.)Enter Mission Control, and then click the desktop you want.

Press Control-

or Control-

or Control- to rotate to the previous or next desktop.

to rotate to the previous or next desktop.

When you make a switch, you see a flash of animation as one screen flies away and another appears. Now that you’re “on” the screen you want, open programs and arrange windows onto it as usual.

Tip

What if you’re using Spaces, and you want to drag something from one screen (like a photo in Photos) into a window that’s on a different screen (like an outgoing email message)?

There are two ways; take your pick. First, you can start dragging whatever it is—and then, in mid-drag, press the keystroke for Mission Control (usually fn-F9); complete the drag directly onto the other Space, and even into the relevant window in that Space.

Another approach: Start dragging. With the mouse button still down, press ![]() -Tab to open the application switcher. Continue the drag onto the icon of the receiving program, and still keep the mouse button down. MacOS switches to the appropriate virtual screen automatically.

-Tab to open the application switcher. Continue the drag onto the icon of the receiving program, and still keep the mouse button down. MacOS switches to the appropriate virtual screen automatically.

Deleting a Desktop

To delete a desktop, enter Mission Control. Point to one of the screen thumbnails without clicking until a ![]() appears in its corner; click it. The desktop disappears, and whatever windows were on it get shoved onto your main desktop.

appears in its corner; click it. The desktop disappears, and whatever windows were on it get shoved onto your main desktop.

Tip

If you don’t have the 1½ seconds to wait for the ![]() to appear, then press Option as you point. The Close button appears instantly.

to appear, then press Option as you point. The Close button appears instantly.

In apps using Full Screen mode, the symbol is different; instead of ![]() , it looks like this:

, it looks like this: ![]() . When you click, the desktop flies off the Spaces bar into the main part of your screen. That app is now a plain-vanilla window thumbnail , just like all the others in Mission Control.

. When you click, the desktop flies off the Spaces bar into the main part of your screen. That app is now a plain-vanilla window thumbnail , just like all the others in Mission Control.

The Finer Points of Spaces

Yes, Spaces is an advanced feature. But there are actually advanced features within this advanced feature. For example:

Rearrange your Spaces. Open Mission Control, and then drag the Space thumbnails around horizontally.

Note

If you’ve decided to turn on the Dashboard as a Space, as described later in this chapter, you can even drag the Dashboard out of its traditional left-side position. Put it off to the right of the other Spaces, for all Apple cares.

Multiple monitors. If you have a second monitor connected to your Mac (or even several), each one can have its own set of Spaces.

If “Displays have separate Spaces” is turned on in the Mission Control panel of System Preferences (Figure 6-12), then each monitor has its own set of Spaces. When you use one of the gestures or keystrokes for switching Spaces, you affect the Spaces on only one monitor: the one that contains your cursor at the moment.

Move a window to a different Space. Of course, you can always move a window to a different Space by dragging its tiny icon within Mission Control. But there are two faster ways.

First, you can drag a window (using its title bar as a handle) all the way to the edge of the screen. Stay there with the mouse button still down. After about a second, the adjacent screen slides into view; you’ve just moved the window.

Second, switch to the new Space. Hold your mouse down on the app’s Dock icon; from the shortcut menu, choose Options→Assign To→This Desktop. The Mac whisks that app’s windows from whatever other screen they’re on to this screen.

Move a window to all Spaces. Usually, you slap each app (or each window) onto only one Spaces desktop. Your web browser on Space 1. Email on Space 2. And so on.

Sometimes, though, you might want one app’s windows on all your desktops—perhaps because you use it so often, you want it always with you. The Finder and System Preferences are great examples. Or maybe your calendar app, your browser, or your email program.

To do that, hold the mouse button down on the program’s Dock icon until the shortcut menu appears. From this menu, choose Options→Assign To→All Desktops.

Wallpaper for every desktop. Coolly enough, though, you can set a different wallpaper photo (desktop photo) to each Space. You might find it easier to get your bearings that way. When you restart the computer, the Mac will remember not just which Spaces you had open and what was on them, but also what pictures lay behind them.

You can go about assigning desktop pictures in two ways. First switch to the Space whose picture you want to change. Then either open System Preferences→Desktop & Screen Saver→Desktop, or right-click or two-finger click a blank spot on the existing desktop background, and choose Change Desktop Background.

Note

In both cases, you may have to move the System Preferences window onto your current Space. You can do that by popping into Mission Control.

Either way, you wind up in the Preferences panel for choosing desktop wallpaper. Click the backdrop you want for this screen. Then switch to the next Space and repeat.

Two Eccentric Spaces Settings

In System Preferences→Mission Control, two settings govern the way Spaces works:

Automatically rearrange Spaces based on most recent use. If this option is turned on, then macOS will constantly rearrange your virtual desktops so that the most recently used ones are first. (The most recent one becomes Desktop #2, since Desktop #1 is always your main desktop.)

The point, of course, is to make it quick and easy to return to whatever you were doing most recently. But if you find it disorienting to have your desktops constantly changing their sequence, you can turn this option off.

When switching to an application, switch to a Space with open windows for the application. There must be some clearer way to write this checkbox.

In any case, it means that when you click the Dock icon for a running program, you jump to the Space that contains that program’s open windows already, instead of leaving you on the current Space.

For example, suppose you’re working in your browser on Desktop #3. Then you click the Mail icon on the Dock. If this option is turned on, you jump to Desktop #2 (or wherever you’ve been already working in Mail). If it’s not turned on, Mail jumps to the foreground, but you won’t see any windows—they’re stranded back on Desktop #2.

Dashboard

As you know, the essence of using a computer is running programs, which often produce documents. In macOS, however, there’s a third category: a set of weird, hybrid entities that Apple calls widgets. They appear, all at once, on a virtual desktop called the Dashboard (Figure 6-15).

Truth is, the Dashboard’s days are numbered. For one thing, this feature comes turned off in High Sierra. For another, the information modules of your Today panel (Figure 6-15) are also called widgets—and they feel a lot newer and more immediate than the Dashboard’s.

Figure 6-15. The Dashboard is a fleet of miniprograms that convey or convert all kinds of useful information, on a Spaces screen all their own. You get rid of the Dashboard either by pressing the same key again (F4 or whatever), by swiping three fingers to the right on your trackpad, or by clicking anywhere except on a widget.

But if you’re still interested, here’s how the Dashboard works.

Turn on the Dashboard Feature

Open System Preferences→Mission Control. From the Dashboard pop-up menu, choose either As Space (the Dashboard will appear on its own desktop) or As Overlay. That option makes the Dashboard widgets float on top of whatever you’re doing.

Opening the Dashboard

Once you’ve brought the Dashboard back from the dead, here’s how you open it:

If you’ve set up the Dashboard as a Space, well, it’s one of your virtual desktops. Swipe to the left with three fingers on your trackpad—repeatedly, if necessary—until you reach the far-left “desktop.” (On a Magic Mouse, swipe with two fingers.)

Or just open Mission Control, and then click the Dashboard thumbnail at the top left of the screen.

If you’ve set up the Dashboard as an overlay, press the Dashboard keystroke.

On older Macs, that would be F4, bearing the Dashboard logo (

). On more recent Macs, where the F4 key bears a Launchpad icon (

). On more recent Macs, where the F4 key bears a Launchpad icon ( ) instead, the keystroke is F12. (If F12 adjusts the volume when you press it, then you must hold down the fn key as you press F12.) In all of these cases, you can change the Dashboard keystroke to whatever you like, as described in “Dashboard Preferences”.

) instead, the keystroke is F12. (If F12 adjusts the volume when you press it, then you must hold down the fn key as you press F12.) In all of these cases, you can change the Dashboard keystroke to whatever you like, as described in “Dashboard Preferences”.

Tip

Dashboard is an actual program, with an icon of its own in your Applications folder. If you’re desperate, you can always open it with a double-click or by using any of the usual program-opening tricks.

Using Dashboard

If you do, in fact, manage to open Dashboard, you now see the display shown in Figure 6-15. Welcome to the Dashboard.

These weird, hybrid entities are like little web pages. They’re meant to display information, much of it from the Internet, and they’re written using web programming languages like HTML and JavaScript.

Mastering the basics of Dashboard won’t take you long at all:

To move a widget, drag it around the screen. (Click anywhere except on a button or a control.)

To close a widget, press the Option key as you move the mouse across the widget’s face. You’ll see the

button appear at the widget’s top-left corner; click it.

button appear at the widget’s top-left corner; click it.To open a closed widget, click the big

button at the bottom of the screen. Now the Widget Browser appears (Figure 6-16), as described in the next section. Open the widget you want by clicking its icon.

button at the bottom of the screen. Now the Widget Browser appears (Figure 6-16), as described in the next section. Open the widget you want by clicking its icon.To hide one of Apple’s widgets, or to delete one you’ve installed yourself, use the Widget Browser described next.

The Widget Browser

The Widget Browser screen appears when you click the big ![]() button at the bottom of the Dashboard. As shown in Figure 6-16, it’s simply a master collection of every widget on your Mac, even the ones that you haven’t dragged onto the main Dashboard screen. Its goal in life: managing all your other widgets.

button at the bottom of the Dashboard. As shown in Figure 6-16, it’s simply a master collection of every widget on your Mac, even the ones that you haven’t dragged onto the main Dashboard screen. Its goal in life: managing all your other widgets.

For example, you can enter icon-deleting mode by holding your cursor down on any one of them; they all start wiggling—and displaying the ![]() button at the top-left corner.

button at the top-left corner.

Note

Even in wiggling-icon mode, you’re not allowed to delete Apple’s widgets—only ones you’ve downloaded and installed yourself.

Figure 6-16. The Widget Browser works exactly like the Launchpad. Move widget icons around by dragging. Drag one widget on top of another to create a folder. Search using the box at the top of the screen. Start them wiggling, for ease of mass deletion, by holding your cursor down on any icon, or by clicking the big  button. Read “Launchpad”–“Windows That Auto-Reopen” again, taking care to mentally substitute the word “widget” for “app.”

button. Read “Launchpad”–“Windows That Auto-Reopen” again, taking care to mentally substitute the word “widget” for “app.”

But what you’ll do here most often is simply click a widget’s icon to install it onto the main Dashboard screen.

(To close the browser without pulling a new icon out of it, click anywhere on the background.)

The Widget Browser also harbors the godlike power of the More Widgets button, described in Figure 2-2.

Dashboard Tips

Dashboard is crawling with cool tips and tricks. Here are a few of the biggies:

To refresh a certain widget—for example, to update its information from the Internet—click it and press

-R. The widget instantly twist-scrambles itself into a sort of ice-cream swirl (you’ve got to see it to believe it) and then untwists to reveal the new data.

-R. The widget instantly twist-scrambles itself into a sort of ice-cream swirl (you’ve got to see it to believe it) and then untwists to reveal the new data.You can open more than one copy of the same widget. Just click its icon more than once in the Widget Browser. You wind up with multiple copies of it on your screen: three World Clocks, two Stock Trackers, or whatever. That’s a useful trick when, for example, you want to track the time in more than one city, or when you maintain two different stock portfolios.

If you keep the Shift key pressed when you click the big

button, the Widget Browser fades in, in gorgeous slow motion. Aren’t you just glad to be alive?

button, the Widget Browser fades in, in gorgeous slow motion. Aren’t you just glad to be alive?

Dashboard Preferences

To change the Dashboard keystroke to something other than F4 or F12, open System Preferences→Mission Control.

Here you’ll discover that you can choose almost any other keyboard combination to summon and dismiss the Dashboard, or even choose a screen corner that, when your mouse lands there, acts as the Dashboard trigger. This works exactly as described in “Mission Control keystrokes”.

Note

Yes, you can also change the Dashboard keystroke on the Keyboard→Shortcuts pane of System Preferences. But if you use the Mission Control pane instead, then you can set up a screen corner or a mouse button to trigger Dashboard—not just a keyboard combo.

Widget Catalog

Apple starts you off with 15 standard widgets: Calculator, Calendar, Contacts, Dictionary, ESPN, Flight Tracker, Movies, Stickies, Stocks, Tile Game, Translation, Unit Converter, Weather, Web Clip, and World Clock. They look awfully simple, but some of them harbor a few secrets.

For a detailed guide to each of these widgets, see the free downloadable appendix, “Dashboard Widgets,” on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

More Widgets

Thousands of new widgets, written by other people, are available on the web: games, chat and email notifiers, gas-price reporters, calculators and translators, news and sports updaters, finance and health trackers, and on and on.

To see Apple’s current list of goodies, use one of these tactics:

The short way. Right-click or two-finger click the Dashboard icon in the Dock. From the shortcut menu, choose More Widgets.

The long way. In Dashboard, open the Widgets browser; click More Widgets.

Either way, you go to the Apple Dashboard downloads page. Here you’ll find offerings like the Yahoo Local Traffic widget (gives you the traffic conditions in your area), Air Traffic Control (identifies wireless AirPort base stations within range of your laptop), and TV Tracker (shows what you could be watching on TV right now instead of working). There are also FedEx package trackers, joke-of-the-day widgets, comic-strip-of-the-day widgets, and many other varieties.

When you download a widget, macOS asks if you’re sure you want to install it. If you confirm, macOS downloads it and then displays it proudly in the Widget Browser. Click it to open. (Behind the scenes, it’s been copied into your Home→Library→Widgets folder. Only you will see that Dashboard widget, because it’s been copied into the Widgets folder of your account. Anyone else who has an account on this Mac won’t see it.)

Exposé

Before Mission Control, there was Exposé. It was flexible, it was novel, it was a little confusing. A few years ago, Apple incorporated the main functions of Exposé into Mission Control—but Apple didn’t want to break all those Exposé fans’ hearts. So Exposé is still there, for the benefit of old-timers who don’t like change.

Well, it’s mostly there. There used to be three different Exposé modes. One showed you miniatures of all windows in all programs, one showed you miniatures of all windows in just one program (Figure 6-17, top), and one hid all windows in all programs so you could see the desktop (Figure 6-17, bottom).

These days, only the second and third Exposé functions still exist. (The first one—showing all windows in all programs—is what Mission Control is for.)

You can trigger both of these modes using different combinations of the mouse and keyboard. The following pages cover all of them, but of course you’re not expected to learn all that. Just find the one trigger that seems most convenient, and stick with it.

One-App Exposé

When you trigger Mission Control, you see the thumbnails of all windows in all apps.

But sometimes it’s useful to see only the windows of one app arrayed before you—the app you’re using.

That’s great when you’re web browsing or word processing. This Exposé function makes the program’s windows spread out, and shrink if necessary, so you can click the one you want (Figure 6-17, top).

Here’s how Apple intends for most people to trigger this option:

Swipe down on your trackpad with three fingers. You’re shown the miniatures of your current app’s windows. If you point to an icon on the Dock before you swipe, you trigger Exposé for that app instead. (There’s no equivalent on the Magic Mouse—although if you install the free BetterTouchTool, you can dream up a gesture of your own.)

Note

You have to turn this feature on in System Preferences→Trackpad→More Gestures. Once you’ve done that, you can change this gesture to four fingers on the trackpad using the pop-up menu—handy if you find yourself triggering the function by accident.

Press Control-F3 (

). That’s the keystroke on aluminum keyboards. (If you have a plastic keyboard, press F10.)

). That’s the keystroke on aluminum keyboards. (If you have a plastic keyboard, press F10.)

Tip

As noted in the box on the facing page, you can also press fn-F10 or, with some tweaking, F10 alone. Or you can change the keystroke altogether, as described in “Redefining a Keystroke”.

Enter Exposé from the heads-up display. The heads-up display is the macOS application switcher—the row of “These are your open programs” icons—which appears when you press

-Tab.

-Tab.

Figure 6-17. Top: When you trigger one-app Exposé, you get a clear shot at any window in the current program (TextEdit, in this example). In the meantime, the rest of your screen attractively dims. In model Apple apps, like TextEdit and Preview, you even get a little row of icons at the bottom. They represent recently opened files, ready for clicking.

Bottom: Trigger desktop Exposé when you need to duck back to the desktop for a quick administrative chore. Here’s your chance to find a file, throw something away, eject a disk, or whatever, without having to disturb your application windows.

Tap the same key again to turn off Exposé.The cool thing is that once you’ve got that heads-up display open, you can press

or

or  to enter Exposé for whatever program’s icon is highlighted! From there, release the keys and hit Tab to cycle through your open apps.

to enter Exposé for whatever program’s icon is highlighted! From there, release the keys and hit Tab to cycle through your open apps.Use Dock Exposé. Click the program’s Dock icon and hold the button down for half a second. (Or, for faster service, right-click or two-finger click the program’s Dock icon.)

This feature has one chief advantage over the keystroke method: You can Exposé-ize any program’s windows, not just the one you’re using at the moment.

Shove your mouse into whatever corner of the screen you’ve chosen. See “Screen corners” for instructions.

Once you’ve triggered Exposé, you’re not quite finished yet. As shown in Figure 6-17, beneath the window thumbnails, you get to see the icons of documents you’ve worked on recently in this app (at least in enlightened Apple programs like TextEdit).

Desktop Exposé

The other flavor of Exposé is surprisingly handy. It sends all windows in all programs cowering to the edges of your screen, revealing the desktop beneath in all its uncluttered splendor (Figure 6-17, bottom).

Here’s the keystroke scheme:

Current keyboards: Press

-F3 (

-F3 ( ). That’s the trigger for current aluminum keyboards and laptops.

). That’s the trigger for current aluminum keyboards and laptops.

Note

Once again, you can also press fn-F11, or (if you set it up) F11 by itself. See the box on the previous page. You can also install a Show Desktop button on the Touch Bar, if you have one (“The Complicated Story of the Function Keys”).

Plastic keyboards: Press F11.

The windows fly off to the edges of the screen, where they remain—forever or until you tap the keystroke again, click a visible window edge, double-click an icon, or take some other window-selection step.

This trick saves headache and hassle in situations like these:

You’re writing an email message, and you want to attach a file. Tap the desktop Exposé keystroke, and then root around in the Finder until you locate the file you want. Begin to drag it, and then, without releasing the mouse button, tap the desktop Exposé keystroke again to bring back your email window. (Or drag the attachment directly onto your email program’s icon on the Dock and pause until its window thumbnails appear.)

Move your cursor, with the file in mid-drag, directly over the outgoing message window; release the cursor to create the attachment. You’ve just added an attachment from the desktop in one smooth motion.

Tip

You can apply the same life-changing shortcut to dragging a graphic into a page-layout program, a folder of photos into Photos, a sound or graphic into iMovie, and so on.

You want to open a different document. For many people, having access to the entire Finder beats having to use the Open dialog box. Double-clicking the icon you want automatically opens it and turns off Exposé.

You’re on the web, and you want to see if some file has finished downloading. Trigger desktop Exposé to survey the situation on your desktop.

If the layer of open programs is the atmosphere, the Finder is the earth below—and the ability to teleport back and forth is a huge time-saver.

Exposé Tip-O-Rama

Just having your world o’ windows spread out like index cards is magic enough. But these windows are live. You can work with them. Let us count the ways:

Tab through Exposé’d apps. Once you’ve started one-app Exposé and a program’s windows are arrayed before you, press the Tab key. With each tap, you cycle through the open apps, each getting the Exposé treatment in turn. It’s an informative way to inspect what’s happening in each open program without losing your way. (Pressing

-~ does the same thing.) Shift-Tab, as usual, cycles through the programs in the opposite direction.

-~ does the same thing.) Shift-Tab, as usual, cycles through the programs in the opposite direction.

Tip

You can also switch to another app’s microwindows by clicking its Dock icon.

Hold down instead of two presses. Most of the time, you’ll probably use Exposé in two steps. You’ll tap the keystroke once to get the windows out of the way and tap it again to bring them back (if, indeed, you haven’t clicked a window to bring them back).

In some cases, though, you may find it easier to hold down the relevant key. For example, hold down

-F3 (Show Desktop) to see if a file is finished copying to the desktop, and then release the keys to bring back all the windows. (Actually, you can let go of the

-F3 (Show Desktop) to see if a file is finished copying to the desktop, and then release the keys to bring back all the windows. (Actually, you can let go of the  key as soon as you’ve entered Exposé.) For quick window-clearing situations, that method saves you the step of having to press the keystroke a second time to turn off Exposé.

key as soon as you’ve entered Exposé.) For quick window-clearing situations, that method saves you the step of having to press the keystroke a second time to turn off Exposé.Use the spring-loaded Dock. This trick is great when you want to drop a file from one program into a particular window belonging to another.

The most common example: You want to add an attachment to an outgoing email message. In the Finder, locate the file’s icon. Drag it directly onto your email program’s Dock icon—and pause with your finger still on the button. After a half-second, Exposé happens, showing all your email program’s open windows. Now continue your drag onto the miniaturized window of the outgoing message so it’s highlighted, tap the space bar to open it, and then release. Presto! The file is attached.

This trick also works great when you want to drop a photo into a newsletter, for example, or a text clipping into a word-processing document.

Dip into Quick Look. Once you’ve got shrunken windows on the screen, tap your arrow keys to highlight a window (or point with your mouse at one without clicking). A bright-blue border moves from window to window.

At any point, you can press the space bar to make that one window return to life size. You haven’t really activated it—you can’t edit it—but at least you can see it at full size.

And here’s the very cool part: Once you’ve triggered Quick Look like this, you can press the arrow keys to zap other miniwindows back to full size, without having to exit Quick Look. Or, again, point to other windows without clicking. Each zooms in to 100 percent size. (All of this is much easier to do than to imagine.)

You can keep examining your windows at full size until you spot the one you’re after; now tap Return (or click the mouse in the window) to exit Quick Look and Exposé. You’ve just opened that window, and you’re ready to roll.

Tip

Keep in mind that you can change all of these Exposé triggers—keyboard shortcuts, hot corners, and so on. See “Mission Control keystrokes”.

Hiding Programs the Old-Fashioned Way

When it comes to getting windows out of your way, nothing can touch Mission Control and Exposé for speed and entertainment value. Once you’ve mastered those features, the traditional rituals of hiding windows will seem charmingly quaint. “When I was your age,” you’ll tell your grandchildren, “we used to have to hold down the Option key to hide windows!”

But you know the drill at software companies: They giveth, but they never taketh away. All the old techniques are still around for the benefit of Mac fans who use them by force of habit.

Hiding the Program You’re Using

For the purposes of this discussion, when a program is hidden, all its windows, tool palettes, and button bars disappear. You can bring them back only by bringing the program to the front again (by clicking its Dock icon, for example).

If your aim is to hide only the frontmost program, macOS offers a whole raft of approaches. Many of them involve the Option key, as listed here:

Option-click any visible portion of the desktop. The program you were in vanishes, along with all its windows.

Option-click any other program’s icon on the Dock. You open that program (or bring all its windows to the front) and hide all the windows of the one you were using.

Option-click any visible portion of another program’s windows. Once again, you switch programs, hiding the one you were using.

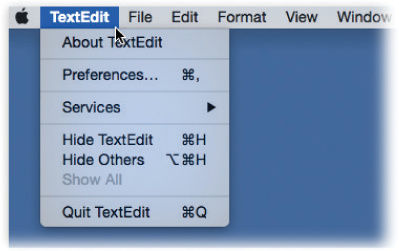

From the Application menu, choose Hide Photos (or whatever the program is). The Application menu is the boldfaced menu that bears the program’s name.

From the program’s Dock icon shortcut menu, choose Hide. You open the shortcut menu, of course, by right-clicking or two-finger clicking. You also get a Hide button if you click-and-hold on the Dock icon for half a second.

When you’ve highlighted a program’s icon by pressing

-Tab to rotate through the running programs, press the letter H key. The program hides itself instantly. Leave the

-Tab to rotate through the running programs, press the letter H key. The program hides itself instantly. Leave the  key down the whole time and, after pressing the H, press Tab again to move on to the next program. If you release the keys while “stopped” on the program instead, you’ll bring it forward rather than hiding it.

key down the whole time and, after pressing the H, press Tab again to move on to the next program. If you release the keys while “stopped” on the program instead, you’ll bring it forward rather than hiding it.Press

-H. This may be the easiest and most useful trick of all (although it doesn’t work in a few oddball programs). Doing so hides the program you’re in; you then “fall down” into the next running program.

-H. This may be the easiest and most useful trick of all (although it doesn’t work in a few oddball programs). Doing so hides the program you’re in; you then “fall down” into the next running program.

Tip

Consider this radical time-saving proposal: Never quit the programs you use frequently. Instead, simply hit ![]() -H whenever you’re finished working in a program. That way, the next time you need it, the program launches with zero wait time.

-H whenever you’re finished working in a program. That way, the next time you need it, the program launches with zero wait time.

In general, macOS’s virtual-memory scheme is so good that there’s almost no downside to leaving your programs open all the time.

To unhide a program and its windows, click its Dock icon again, choose the Show All command in the Application menu, or press ![]() -Tab to summon the heads-up application display.

-Tab to summon the heads-up application display.

Tip

The Dock continues to display the icons of all running programs without any indication that you’ve hidden them. Fortunately, that’s easy enough to fix. All you need is the free program TinkerTool, which is available on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com. It offers a simple checkbox that makes hidden programs appear with transparent Dock icons.

Hiding All Other Programs

Choosing Hide Others from your program’s Application menu means, of course, “Hide the windows of every program but this one.” It even hides your Finder (desktop) windows, although desktop icons remain visible.

Better yet, there’s a keystroke for this command: Option-![]() -H. That’s one small step for keystrokes, one giant leap for productivity geeks.

-H. That’s one small step for keystrokes, one giant leap for productivity geeks.

Tip

If you right-click or two-finger click a program’s Dock icon, you get its shortcut menu, including a Hide command. If you press Option, it changes to say Hide Others. It’s a lot more work than the methods described already, but…you know. One strives for thoroughness.

If this trick interests you, then you might also enjoy its corollary, described next.

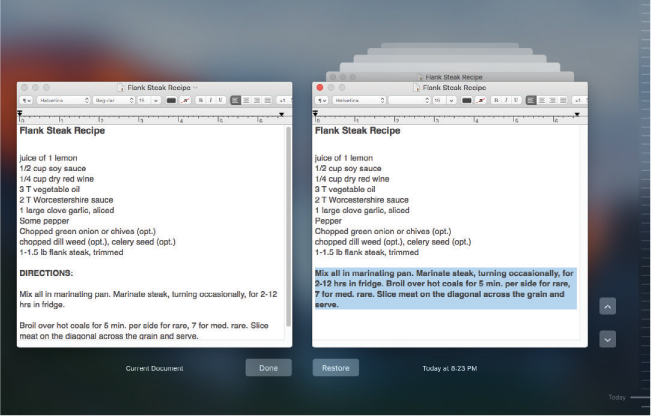

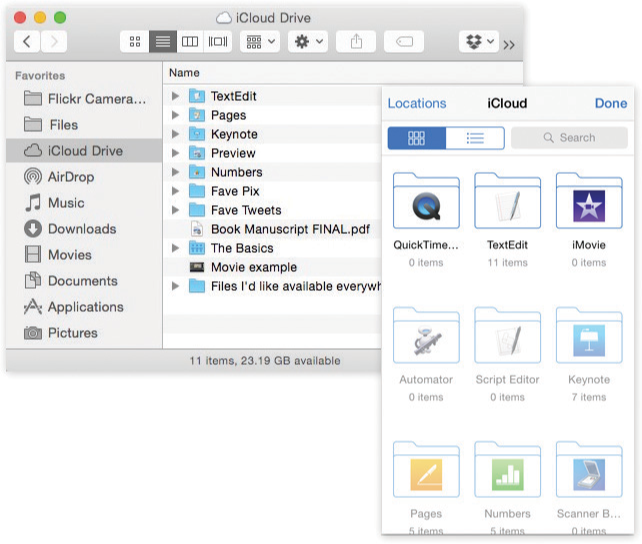

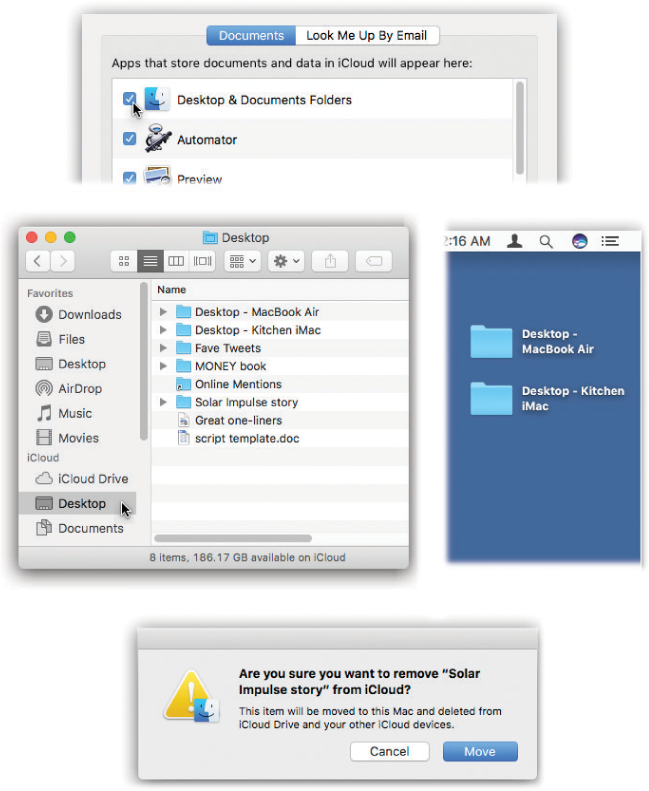

The Bring-Forward, Hide-All-Others Trick