Step 2. Craft Your Presentation

This part of the book should have fireworks exploding all around it, because this is the part of the book that lays out for you a foolproof way to craft a presentation that will be effective, persuasive, and engaging. It pulls together everything else in all the other chapters and explains how to craft, organize, and structure your presentation.

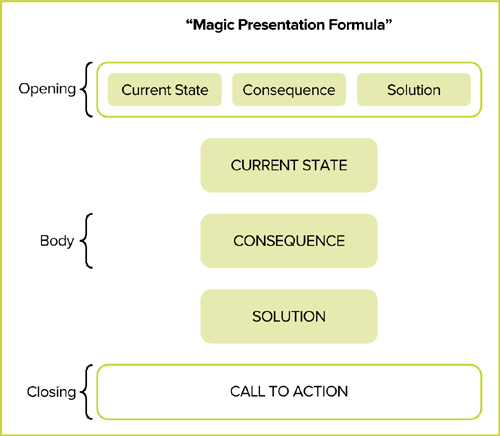

This template for how to structure a presentation is, of course, only one idea. You don’t have to organize your presentation this way. However, it is a powerful formula that works for many people, and it is the formula that I recommend most people use for most types of presentations. I call it the Magic Presentation Formula.

The Magic Presentation Formula

It’s actually pretty simple. Figure A.1 shows the order in which you will actually deliver your presentation, but I’m going to skip around the diagram as I explain each part.

Figure A.1. The Magic Presentation Formula

The call to action

Let’s start at the end of the diagram, which is the end of your presentation. If you completed Step 1 of this chapter, and you’ve therefore done your research, then you should have a clear idea of the goals and objectives of the presentation, as well as the appropriate gap between where people are at the start of the presentation and where you want them to be at the end. The next decision you have to make is what to have as your call to action. What will you ask your audience to do after your talk is over—what will bridge that gap?

For example, if you are preparing a presentation in order to persuade people to donate to a charity, then the call to action will likely be something like writing out a check for $100 to the charity.

You can have more than one call to action; for example, you could have:

• Write out a check for $100 or fill out a credit card form.

• Get three friends to donate as well.

• Volunteer to help at the next fund-raising event.

Because you’ve read the rest of the book, you know that you don’t want too many options in the call to action, or people won’t choose any of them. Don’t offer more than four choices. But there should always be at least one call to action, even if it is something mild, such as reading a book for more information or signing up for a newsletter.

Without a call to action, you are just another person talking; with a call to action that you can build your presentation around, you are a presenter.

The current state

Now that you know your call to action, the next place to spend time is the “current state.” In this book I’ve talked about the old brain. The old brain is very interested in “me, me, me, I, I, I.” It’s easy as the presenter to think that other people will be as excited about your topic as you are. But to other people, it might not be so intrinsically interesting. You’ve got to figure out how to grab the attention and interest of your audience. This is another place that your audience research is so important. If you know your audience, you will know what will grab them.

Here’s an example. A few years ago I was giving a presentation to the CEO and president of a company. I had just completed a study for them in which I looked at how they might want to change their sales process. The study had taken several weeks, including interviews with the CEO and president, several of the sales staff, and other employees. I had lots of data and some important conclusions for them to consider. The call to action would require that they make some fairly major changes in roles, staffing, and their sales process. The result would be worth it, but I had to figure out how to make them see that. Change is not easy.

What is the current state from your audience’s point of view?

I built the presentation around the Magic Presentation Formula, and I focused the presentation on what they cared about. In the body portion of the diagram, you will see a box labeled Current State. You want to spend time in your talk discussing the current state of affairs from the audience’s point of view. In the example that I gave in the previous section, the current state that would get the attention of the president and CEO was that their sales people were spending a lot of time working on their computers rather than being on the phone with, or visiting, customers. This valuable resource was wasting time struggling with formatting Word documents. I had data about how the amount of time spent interacting with customers had declined over the past year, and about how time spent on writing complicated proposals had increased.

The Current State part of your presentation describes what the problem or issue is that needs to change. You want to include stories, pictures, data, statements from others, charts, and graphs to make your point that this is indeed the current state.

The consequences of staying the course

Look again at the body of the magic formula. The next box is labeled Consequences. At this point in the talk, you have outlined the current state, and if you’ve done so from your audience’s point of view, then you should have the attention of your audience. Now you show the consequences of keeping the current state.

In my example, what were the consequences of continuing to have a broken sales process? It’s important that the consequences be stated in terms of what the audience cares about. I could have said that the consequence of not changing the sales process is that the sales people will get frustrated and won’t enjoy their job anymore (which was actually true), but that’s not what the president and CEO really cared about.

From my previous interviews with them, I knew that they cared about a) revenue coming in the door, b) the length of time it was taking to close sales, and c) the ability of the sales people to take on larger territories. Because I knew that this is what they cared most about, that’s what I focused the Consequences part of the talk on. I painted a picture, using stories and potential future numbers, of how these factors would be affected if they stayed the course with the current sales process.

The Consequences part of your presentation describes what is likely to happen in the future if the current state continues, Again, you want to include stories, pictures, data, statements from others, charts, and graphs to make your points.

You have a solution

Next in the magic formula is the solution. In your presentation so far, you’ve described the current state and the consequences of not making any changes. Now it’s time to offer your solution. Instead of keeping the current state, what should they do? What impact will the solution have? What will be different?

In my example, I laid out a revised sales process and also showed how each part of the new sales process addressed their revenue and other goals. If you’ve described the current state and consequences in terms that your audience cares about, then they will be ready to listen to your solution and ready for your call to action.

Here are some more examples.

For a presentation to your team about why the timeline should be changed:

Current state: We’re behind on the project.

Consequences: If we stick to the current milestones, we’ll have to cut back on features or sacrifice quality.

Solution: Let’s see if we can get the final deadline date moved by two weeks.

Call to action: Put together a revised timeline and go talk to our supervisor.

For a presentation to the school board about why they should fund a new playground:

Current state: The current playground is out of date. It doesn’t meet suggested guidelines for safety. We are getting complaints from parents.

Consequences: At some point, someone is going to get hurt and the school will have to deal with a lawsuit.

Solution: Do some targeted fundraising this year, and take advantage of a matching offer from a local business to replace the equipment.

Call to action: Agree to a meeting with a committee that has prepared a plan and budget for the new playground and the fundraising.

The opening

Ironically, I’ve saved discussion of the opening of your presentation for last. That’s because it is so critical to your success. In the magic formula, the opening is actually a mini version of the body of the presentation. In 30–60 seconds, you describe the current state, the consequences, and the solution. This is really hard to do in less than a minute, but it’s important that you keep it short.

In my first example, here was the opening:

“Your sales people are wasting hours every day sitting at their desks formatting Word documents instead of talking to customers. Your sales process is broken. It’s causing you to lose up to four million dollars a year in revenue, doubling the time it takes to get a sale to close and preventing your sales staff from taking on more territory. You can change your sales process and get back on track. In this presentation, I’m going to show you how to increase your revenue by 30 percent in the next 12 months, cut your closing time by half, and increase each sales person’s territory by 20 percent.”

I’m not exaggerating when I say that both the CEO and the president were on the edge of their seats. I had their attention, and I maintained their attention for the next hour.

The Magic Presentation Formula might not work for all your presentations, but it will work for many if not most. Try it out, and I think you will be amazed not only by how effective it is, but also by how much easier you find it to decide what content to put in your presentation, and in what order.