CRAIG WILSON

Flying High

When Craig Wilson’s shutter releases, he is twenty to a hundred feet below his camera as it gently floats through the air hanging from a kite. He doesn’t see what the camera is focused on, and he’s not using his right index finger but rather his left thumb. He says it’s kind of a Zen thing. He just has a feel for where to put the camera.

Wilson admits this kind of photography likely would drive most photographers nuts: you can’t control the lighting and the framing, and there are no test shots or meter readings. Yet he captures images with such grace and beauty that his book, Hanging by a Thread, is now in its third printing since 2006.

Kite delight

As a boy, Wilson flew the usual box kites.

But kites have historically been more than kid’s stuff. The Wright brothers used kites to study aerodynamics so they could build an airplane. Kites lifted antennas for the first transatlantic radio transmission, and kites delivered early weather instruments to the skies. In ancient times, kites were used for signaling during Genghis Khan’s reign, and, religiously, they were used to carry prayers to the gods.

In his late twenties, while working as a carpenter, Wilson gained a renewed appreciation of the kite.

“I fell in love with building kites, because when I build a bookcase it just sits there,” he says. “It can be beautiful and lovely and do its little job, but it doesn’t really do anything. I’d be walking along, and I’d see a place and think, ‘Oh, that would be a lovely place to fly a kite.’ When I build a kite, I take it with me, and then it takes me places.”

His first kite was about 3 feet wide. Within a year, he had built three or four different kites, and fairly soon came the kite with a 20-foot span. “I’m raising this huge kite on its maiden flight with my Canon AE1 around my neck, thinking I better get a picture because I’m not sure I built it to proper scale,” said Wilson. “The bigger the kite, the greater the stress on it. How much bigger do I make the sticks? How heavy a line do I need? Is the stitching going to hold? And there weren’t any books to read with precise directions.”

That’s when it happened, he said. “I’m holding this big beautiful kite with my left hand and taking a picture with my right hand and the light goes on in my head. That kite could lift this camera, and I realized I had to figure it out.”

Wilson designs all of the kites and camera controllers that he uses for his aerial photography.

Other flyers

The very first aerial photos were taken from a hot air balloon in the 1850s. But the idea of sending cameras aloft without their photographers dates back to the 1880s in France where Arthur Batut is credited as the first to use a kite to lift a camera.

How did Batut get the shutter to release? “Perhaps a burning fuse, or a slow burning punk or an ice cube in a clothes pin—I haven’t figured that out,” says Wilson. “Whatever he did, he got only one shot with each lift, and there was little control over when the shutter would release.”

In this country, Wilson’s research uncovered, the revolutionary photographer George Lawrence from Chicago, who built huge cameras that he lifted by kites to take panoramic photos. Probably his most famous aerial photo is one of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake. It is a panoramic view of the city still smoking from all the fires. Lawrence earned a lot of money from that photo, and afterwards he made a career out of shooting aerial photos of cities.

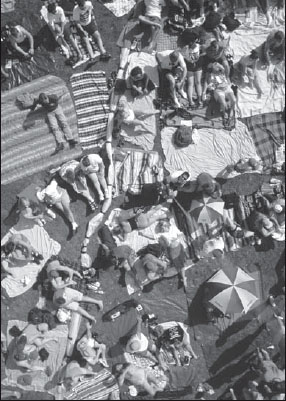

Wilson’s overhead shots change the viewer focus. This shot of a bicycle race, Wilson observes, is “more about the shadow than the cyclist.”

Armed with his research, Wilson set out to begin flying and refining his craft.

Lift off

Once the airplane came along, using kites for aerial photography became less desirable. So, when Wilson began lifting cameras with kites in 1986, he was part of a rare group still doing it.

“I’d guess there were fewer than 100 people lifting cameras with kites when I started, and most of them were very primitive using duct tape and rubber bands, which is how I started,” says Wilson. Even though it had been done years before, Wilson says it was like starting from scratch because everything was still so amateurish.

The first camera Wilson lifted was a Canon. He built a little timer with a rubber band that after so many minutes would pull the arm, and the camera would take a picture. That meant for a roll of thirty-six exposures he had to lift thirty-six times. Up and down, up and down. It would take a whole afternoon to shoot a single roll of film, and he didn’t necessarily get to set up his shot. When the minute was up, click. But that didn’t stop him. Neither did the fact that the first photos he took were awful. They were blurry and poorly aimed.

Recalling that first lift, Wilson says, “It was exciting, I was in my backyard taking photos of my house, just above treetop. That’s maybe 40 or 50 feet, a bird’s-eye view. It was awesome, everything worked as it should. I couldn’t wait for the pictures to develop, but they were awful. I realized I had many improvements to make and that might include buying a better camera.”

The next camera had an interval timer that would take a picture every 60 seconds and advance until film was gone. That made the process a lot easier by eliminating the up and down, but it still had limitations. There was still no precise control over when the shutter would release. But he kept trying and finally thought he had something.

According to Wilson, kite photography can give the pictures humanity that cannot be achieved from the wing of a plane.

“I took a shot of the Madison state capitol that I thought was really nice,” he said. “I brought the photo to Madison magazine. I thought the editor would love it. It was such a unique view.” The editor got out a really big loupe and dashed Wilson’s hopes. The camera couldn’t shoot at a fast enough shutter speed, and the photos weren’t sharp enough. So Wilson went back to the garage to design a new camera controller for his next camera.

Perseverance pays off

After a few months Wilson emerged from the garage with a remote control paired to the camera that would launch his success. “The first place I took my new set up was to the parking lot by Camp Randall football stadium where the University of Wisconsin Badgers were playing football,” recalls Wilson. “I launched the kite, lifted the camera and shot a twenty-four-exposure roll. Then I scurried off to get them processed and was blown away by what I saw.”

There are things you can do from a kite that you can’t do from an airplane or a helicopter. For example, you can hover at tree line or float over a picnic, a park or a building. You can give the pictures humanity that cannot be achieved from the wing of a plane, Wilson explains.

Wilson’s photos from the football game were so good that a postcard company bought about six of them, and they became the company’s bestselling postcard for several years. “I think they even landed in Madison magazine and another well respected local magazine,” Wilson recalls.

This is Wilson’s twenty-fifth year of flying, and he tries to average one lift a week. He estimates he has lifted his camera probably 10,000 times.

Digital opens floodgates of possibilities

“I love digital. I can bring the camera down and leave the kite up,” says Wilson. “Perhaps I see something that is behind a row of trees, or perhaps I wasn’t aware of the way the shadows were falling. I can quickly send the camera back up and get a great photo from a wonderful hidden surprise that the camera showed me, something that was happening at that moment that I would have missed if I had to get a roll of film developed.”

Wilson enjoys events with movement like bicycle races or boating events. He explains, “I look to where the bicycle racers are going to cast a shadow and try to set up for that shot, making the photo more about the shadow than the cyclist. It changes the viewer focus. Is the picture of the cyclist or the shadow?”

Living in Wisconsin, Wilson has many beautiful photos of ice events, from kites on ice to ice fishermen, skiers, skaters, and ice boating. Often when looking at one of Wilson’s photos it takes a moment to figure out what you are looking at because the perspective is so different from what we usually see.

Finding a niche market

Some of Wilson’s best clients are engineering firms. If they are designing a new roundabout for an intersection, they want to see before and after photos. “My camera might only be at 100 feet off the ground, and they can see in great detail exactly how their project will interface with the site,” says Wilson. “They can literally count bushes and estimate how it will all work out. It’s not like the aerial shots that lose the perspective of the human scale, which a lot of aerials do. You don’t see human sized objects from an airplane. You can read the name on a mailbox with a camera flying from a kite. You can even find yourself in a group photo.”

There are a variety of reasons why companies want a photo by Wilson. Some clients might simply want to see what a view will look like from various floors at a location where they plan to build an office, or they want to closely match original design renderings and models. They can avoid the expense of using a large crane to get a similar shot. Kite shots also provide an environmentally green method that won’t have a negative impact on the wildlife or habitat in sensitive areas.

Engineering firms are some of Wilson’s best customers. He frequently takes before and after pictures of new roundabout intersections like this one.

Wilson currently uses three cameras and several different kites, depending on the job. “It’s like golf,” says Wilson. “You wouldn’t take just one club—you need different clubs for different shots. I need a different kite depending on the wind speed or the launch area. Another challenge I enjoy is designing kites that can be broken down easily, which is especially helpful if a part needs to be replaced. Or, sometimes I need a kite that is small enough to fit in a backpack.

“I am often in city areas and places that people wouldn’t necessarily think of to fly a kite, and it becomes a performance,” said Wilson. “I sometimes draw a crowd in urban environments. People see this beautiful kite and they say, ‘What’s he doing … oh, it’s a camera, and then they just watch. It’s very satisfying and a lot of fun.”

Wilson shoots with a Nikon and two Pentax cameras, 12-14 megapixels. He uses fixed focus wide-angle lenses for the greater depth of field and better focus, and to stay light. If he wants to zoom in on something, he just moves the camera closer.

Each camera has its own controller, which is part of the fun for Wilson. He designs and builds the camera controllers and the kites. Does he ever hope to advance the technology to the point of seeing what his viewfinder sees? “Not really. If I’m looking down at what the camera sees, then I’m no longer flying the kite,” Wilson says. “It’s a lot more fun not knowing what I will see until I bring the camera down. I’ve got different ways that give me clues to what the camera is doing, but having that direct visual feedback isn’t as important as you might think.”

Also important to Wilson is maintaining a system that doesn’t require a helper. That way he is free to fly whenever he wants to, and, in particular, to meet his goal of flying once a week.

Ice boating is one of the many ice events Wilson photographs in Wisconsin.

Constant challenges and new opportunities

Wilson may have found a unique application for kiting, but he remains an enthusiast of kiting for its own sake. Wilson is part of a performance troupe called Guildworks that uses specialized kites to entertain and amaze. The Guildworks group has flown its kites for Ben Franklin’s 300th birthday party at the Ben Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, the opening ceremonies at the Rider Cup golf tournament in Kentucky, Kites on Ice in Wisconsin, and at the grand opening of the Desert Living Center in Las Vegas.

Within the small community of kite devotees, Wilson enjoys a tremendous reputation. Wilson was invited to China to fly a kite on ice skates to celebrate the opening of a world ice arena in Hangzhou and has flown kites for a Starbucks coffee advertisement filmed in New York City.

He earned a trip to South Africa in the late 1990s to help a group planning a kite fund-raising festival for Cape Mental Health in Capetown. The group flew him in a week early to take photos of the local tourist sites and of the sponsors’ facilities. Some of his photos were framed and auctioned off as part of the fund-raiser.

The highlight of that trip and of his photographic career (so far) was being taken to Robben Island, the prison where Nelson Mandela had been held for twenty-six years. It was in the process of becoming a memorial and museum after having been closed a year or two earlier.

“Here I am flying this kite in this razor wire compound,” he recalled. “It was very symbolic, I am looking at this beautiful kite in the beautiful blue sky, and I am standing in this prison ground looking at a very depressing razor wire covered facility. My camera caught a tiny little cemetery. The headstones seemed to have been sandblasted bare. It was an almost ghostlike experience, and to get these aerial views of it was astounding.

“It’s always discovery and an adventure,” Wilson says. “I guess my experience is a bit beyond the normal photography adventure, because I am tapping into this magnificent energy—the wind—and I am at its mercy. I have to relinquish an element of control and just go with the natural element, which ultimately dictates what’s going to happen.”

Wilson’s career isn’t for everyone, but he believes if you take your camera and put it into the part of your life that you genuinely have an interest in and love, you might possibly end up doing something that no one else is doing. “If you want to do what someone else is doing, they are already there, and you have to chase them,” he says. “So whatever you are into, be it tulips or bicycling or dog grooming, that’s probably where you should bring your art. That’s what makes it really fulfilling. It will never get tiring or boring. I am always pushing the limits and looking to try something new.”

Deb Heneghan is a freelance writer and photographer based in Madison, Wisconsin.