Chapter 6

Coupling the Income Statement and Balance Sheet

In This Chapter

![]() Seeing connections between the income statement and balance sheet

Seeing connections between the income statement and balance sheet

![]() Fitting key pieces into the balance sheet puzzle with operating ratios

Fitting key pieces into the balance sheet puzzle with operating ratios

![]() Adding assets to the balance sheet

Adding assets to the balance sheet

![]() Examining debt versus equity on the balance sheet

Examining debt versus equity on the balance sheet

Every time you record a sale or expense entry by using double-entry accounting, you see the connections between the income statement and balance sheet (see Book I, Chapter 2 for more about double-entry accounting and the rules for debits and credits). A sale increases an asset or decreases a liability, and an expense decreases an asset or increases a liability. Therefore, one side of every sales and expense entry is in the income statement, and the other side is in the balance sheet. You can't record a sale or an expense without affecting the balance sheet. The income statement and balance sheet are inseparable, but they aren't reported that way!

To properly interpret financial statements — the income statement, the balance sheet, and the statement of cash flows — you need to understand the links between the three statements. Unfortunately, the links aren't obvious. Each financial statement appears on a separate page in the annual financial report, and nothing highlights connections between related items on the different statements. In reading financial reports, non-accountants — and even some accountants — usually overlook these connections.

Chapter 2 presents the income statement, and Chapters 3 to 5 cover the balance sheet. This chapter stitches these two financial statements together and marks the connections between sales revenue and expenses (in the income statement) and their corresponding assets and liabilities (in the balance sheet). Book V, Chapter 2 explains the connections between the amounts reported in the statement of cash flows and the other two financial statements.

Rejoining the Income Statement and Balance Sheet

When reading financial statements, you should “see,” in your mind's eye, lines connecting related amounts on the income statement and balance sheet. Because financial reports don't offer a clue about these connections, actually drawing the lines, as done in the next section, may help you see the connections.

Seeing connections between accounts

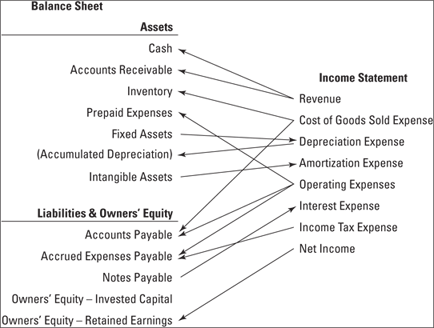

Here's a quick summary explaining the lines of connection between items on the income statement and balance sheet, as shown in Figure 6-1, starting from the top and working down:

- Making sales (and incurring expenses for making sales) requires a business to maintain a working cash balance.

- Making sales on credit generates accounts receivable.

- Selling products requires the business to carry an inventory (stock) of products. When inventory is sold, the inventory cost is posted to cost of goods sold — an expense account.

- Acquiring inventory items on credit generates accounts payable.

- Prepaying expenses (such as insurance premiums) creates an asset account balance.

- Depreciation expense is recorded for the use of fixed assets (long-term operating resources).

- Depreciation is also recorded in the accumulated depreciation contra account (instead of decreasing the fixed asset account). (For more about contra accounts, see Book IV, Chapter 3.)

- Amortization expense is recorded for limited-life intangible assets.

- Operating expenses is a broad category of costs encompassing selling, general, and administrative expenses:

- Some of these operating costs are prepaid before the expense is recorded, and until the expense is recorded, the cost stays in the prepaid expenses asset account.

- Some of these operating costs involve purchases on credit that generate accounts payable.

- Some of these operating costs are from recording unpaid expenses in the accrued expenses payable liability.

- Borrowing money on notes payable generates interest income for the lender and interest expense for the borrower.

- Net income results in income tax expense. A portion of income tax expense for the year may be unpaid at year-end. The unpaid balance is recorded in the accrued expenses payable liability.

- Earning net income increases retained earnings, which also increases the equity section of the balance sheet.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-1: Connections between income statement and balance sheet accounts.

Using transactions to explain the connections

Figure 6-1 provides a nice visual tool to connect balance sheet and income statement accounts. Keep that tool in mind as you consider some common accounting transactions, as explained in the following sections.

Estimating a receivable balance at year-end

Figure 6-1 shows how the sales account (in the income statement) is connected to accounts receivable in the balance sheet. An accountant can use historical trends in these two accounts to project an accounts receivable balance at year-end.

Suppose for the year just ended, a business reports $5,200,000 sales revenue, as shown in Figure 6-2. All sales are made on credit (to other businesses). Historically, the company's year-end accounts receivable balance equals about five weeks of annual sales revenue; in other words, an amount equal to five weeks of annual sales revenue is not yet collected at the end of the year.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-2: Income statement of a business for the year just ended.

Sales are level throughout the year. To determine the amount of accounts receivable to expect in the business's year-end balance sheet, divide the $5,200,000 by 52 weeks to get $100,000 per week. After that, multiply by 5 weeks to get $500,000 of sales revenue in accounts receivable.

Projecting ending inventory balance and accounts payable

If historical trends allow you to project accounts receivable, you may also be able to forecast an ending balance in inventory and a year-end accounts payable figure.

Assume the same business has an annual cost of goods sold expense of $3,120,000 (refer to Figure 6-2), and its ending inventory balance historically equals about 13 weeks of annual sales. You can expect the amount of inventory in its year-end balance sheet to be: $3,120,000 ÷ 52 weeks = $60,000 average cost of goods sold per week × 13 weeks = $780,000.

Historically, the business's accounts payable for inventory purchases equals about four weeks of annual cost of goods sold. (Note: The accounts payable balance also includes an amount from purchases of supplies and services on credit, but this example concerns only the amount of accounts payable from inventory purchases.) Here's how you calculate the amount of accounts payable for inventory purchases you'd expect to see in its year-end balance sheet: $3,120,000 ÷ 52 weeks = $60,000 average cost of goods sold per week × 4 weeks = $240,000.

Accruing other year-end expenses

A company has other expenses in addition to cost of goods sold. You may be able to estimate the amount of other expenses that are accrued at year-end (see Book I, Chapter 3 for more about accruals).

Assume a business has annual operating expenses of $1,378,000 (which excludes depreciation, amortization, interest, and income tax expenses). Historically, its year-end balance of accrued expenses payable equals about six weeks of its annual operating expenses. Ignoring accrued interest payable and income tax payable, you'd expect the amount of accrued expenses payable in its year-end balance sheet to be: $1,378,000 ÷ 52 weeks = $26,500 average operating expenses per week × 6 weeks = $159,000.

For this same business, the average amount borrowed on notes payable during the year was $1,500,000. The average annual interest rate on these notes was 6.5 percent. To determine the amount of interest expense you'd find in the business's income statement for the year: $1,500,000 average notes payable × 6.5 percent interest rate = $97,500.

Introducing Operating Ratios

One way to connect a balance sheet account to the income statement is to use a ratio. Accountants use a variety of ratios to measure financial performance. This section explains the use of operating ratios.

An operating ratio expresses the size of an asset or liability on the basis of sales revenue or an expense in the annual income statement. A normative operating ratio refers to how large an asset or liability should be relative to sales revenue or its related expense. You can use operating ratios to judge how a business is performing compared to its own past performance and to the performance of other companies in the same industry.

Comparing expected with actual operating ratios

To manage businesses, managers compare expected performance with actual results. As explained previously, a normative operating ratio is a benchmark. It's a result that's expected or planned. Your actual ratio may differ. The process of evaluating the difference between planned and actual results is called variance analysis.

Suppose a business, Company X, makes all its sales on credit and offers its customers one month to pay. Very few customers pay early, and some customers are chronic late-payers. To encourage repeat sales, the business tolerates some late-payers. As a result, its accounts receivable balance equals five weeks of annual sales revenue. Thus, its normative operating ratio of accounts receivable to annual sales revenue is 5 (weeks) divided by 52 weeks, which equals 9.615 percent of sales revenue.

The 5:52 operating ratio is the normative ratio between accounts receivable and annual sales revenue; it's based on the sales credit policies of the business and how aggressive the business is in collecting receivables when customers don't pay on time. When you consider actual results, minor deviations from the normative ratios are harmless. However, significant variances deserve serious management attention and follow-up. Check out Book VII, Chapter 4 for more on variances.

Generating balance sheet amounts by using ratios

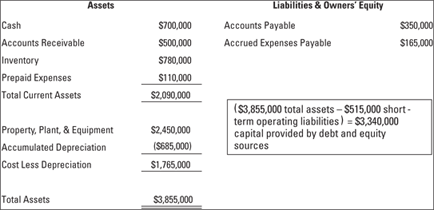

Figure 6-2 presents the annual income statement of Company X. From the sales revenue and expenses reported in the income statement, you can determine the balances of several asset and liability accounts by using the normative operating ratios for the business.

Presenting ratios used for balance sheet calculations

Operating ratios can be expressed in terms of a number of weeks in a 52-week year or as percentages of annual sales revenue or annual expense. The normative operating ratios for the business whose income statement is presented in Figure 6-2 are as follows (expressed as weeks in a year):

- Cash: 7/52 or seven weeks of annual sales revenue

- Accounts receivable: 5/52 or five weeks of annual sales revenue

- Inventory: 13/52 or 13 weeks of annual cost of goods sold

- Prepaid expenses: 4/52 or four weeks of annual selling and general expenses

- Accounts payable for inventory acquisitions: 4/52 or four weeks of annual cost of goods sold

- Accounts payable for supplies and services bought on credit: 4/52 or four weeks of annual selling and general expenses

- Accrued expenses payable for operating expenses: 6/52 or six weeks of annual selling and general expenses

Calculating balance sheet amounts

Using the operating ratios for Company X, whose income statement appears in Figure 6-2, you can determine the balances for the assets and liabilities driven by its sales revenue and expenses. Take the following steps:

- Determine the revenue or expense account to be used for the operating ratio.

- Divide the revenue or expense dollar amount by 52 weeks to compute a weekly level of activity.

- Multiply the fraction you calculated in Step 2 by the total dollar amount of revenue or expense. The result is the dollar amount in the balance sheet account.

Using the operating ratios presented in the earlier section, “Presenting ratios used for balance sheet calculations,” you can calculate dollar amounts for the balance sheet accounts:

- Assets

- 7/52 × $5,200,000 sales revenue = $700,000 Cash

- 5/52 × $5,200,000 sales revenue = $500,000 Accounts receivable

- 13/52 × $3,120,000 cost of goods sold = $780,000 Inventory

- 4/52 × $1,430,000 selling and general expenses = $110,000 Prepaid expenses

- Liabilities

- (4/52 × $3,120,000 cost of goods sold) + (4/52 × $1,430,000 selling and general expenses) = $350,000 Accounts payable

- 6/52 × $1,430,000 selling and general expenses = $165,000 Accrued expenses payable

These asset and liability balances are normative, not the actual balances that would be reported in the business's balance sheet. See the section, “Comparing expected with actual operating ratios” earlier in this chapter for additional guidance.

Tackling other balance sheet issues

You may find the list of ratios to be straightforward. Calculating other amounts in the balance sheet requires more explanation. These balance sheet accounts aren't typically derived by using an operating ratio. Consider these points:

- Intangible assets: The business doesn't own intangible assets and therefore doesn't have amortization expense. An intangible asset, such as a patent or trademark, isn't usually derived by using an operating ratio.

- Accrued interest payable: This year-end liability typically is a relatively small balance compared with the major assets and liabilities of a business. Also, the expense that drives this balance isn't an operating expense. The year-end balance of accrued interest payable depends on the terms for paying interest on the business's debt.

- Accrued income tax payable: Income tax payable is similar to interest payable. This balance is typically smaller than the other amounts in the balance sheet. The expense that drives this balance is the income tax status of the business and its policies regarding making installment payments toward its annual income tax during the year. Income tax expense isn't considered an operating expense.

- Fixed assets: The ratio of annual depreciation expense to the original cost of fixed assets can't be normalized. Different fixed assets are depreciated over different estimated useful life spans. Some fixed assets are depreciated according to the straight-line method and others according to an accelerated depreciation method. (See Book III, Chapter 1 for more about these and other depreciation methods.)

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-3: Partial balance sheet with asset and liability balances.

Adding Fixed Assets, Depreciation, and Owners’ Equity

One asset is obviously missing in the partial balance sheet shown in Figure 6-3: the fixed assets of the business. Fixed assets are usually physical, tangible assets you use to make money in your business (see Chapter 3). Virtually every business needs these long-lived economic resources to carry on its profit-making activities. This section adds fixed assets, depreciation, and owners’ equity to the balance sheet detail.

Dealing with fixed assets and depreciation

Unfortunately, you can't use an operating ratio method to determine the balance sheet amount for fixed assets or depreciation expenses for two reasons:

- Different fixed assets are depreciated over different estimated useful life spans, using different depreciation methods (such as straight-line and accelerated), so you can't simply divide total depreciation expense by the original costs of the fixed assets to compute a consistent ratio for expensing fixed assets.

- Generalizing about the cost of fixed assets relative to annual sales revenue is very difficult. As a ballpark estimate for this ratio, you could say that annual sales revenue of a business is generally between two to four times the total cost of its fixed assets, but this ratio varies widely from industry to industry and even among companies in the same industry.

The cost and accumulated depreciation of a business's fixed assets depend on these factors:

- The type of depreciation method used

- When the assets were purchased (recently or many years ago)

- Whether the business leases or owns these assets

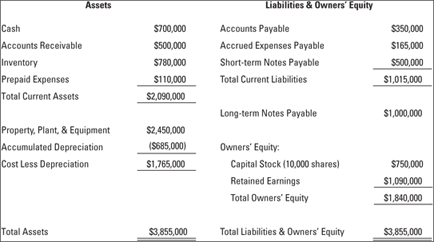

Fitting in fixed assets and depreciation to the balance sheet

Next, you see where fixed assets and depreciation fit into the balance sheet. Take a look at the partial balance sheet shown in Figure 6-4. Notice the following:

- The total current asset number ($2,090,000) is the same number you see in Figure 6-3.

- Figure 6-4 adds three numbers to the asset column. Note that these three numbers are below current assets. That means that the added numbers are long-term assets — assets that will be used over several years.

- Total assets in Figure 6-4 are $3,855,000. Note that this total doesn't balance with total liabilities and equity ($350,000 + $165,000). In fact, the right column doesn't list any equity. That issue is addressed in the “Tacking on owners’ equity” section later in the chapter.

Book I, Chapter 1 explains the fundamental accounting equation, which dictates that Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ equity. Because that isn't the case in Figure 6-4, this balance sheet is incomplete. You fill in the remaining balance sheet numbers as you move through the chapter.

Book I, Chapter 1 explains the fundamental accounting equation, which dictates that Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ equity. Because that isn't the case in Figure 6-4, this balance sheet is incomplete. You fill in the remaining balance sheet numbers as you move through the chapter.

Calculating depreciation

Now that you see where fixed assets and depreciation show up in the balance sheet, you can go over the calculation of depreciation. Book III, Chapter 1 covers deprecation in detail. This section gives a more general discussion.

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-4: A partial balance sheet that includes assets and liabilities.

Here are the accounts related to fixed assets in Figure 6-4:

$2,450,000 property, plant, and equipment – $685,000 accumulated depreciation = $1,765,000 cost less depreciation

Accumulated depreciation is the total of all depreciation expense since the asset was purchased. Property, plant, and equipment is a common term for fixed assets.

If all the assets were bought on the same day, and no depreciation had been expensed, the total property, plant, and equipment balance would be ($2,450,000 + $685,000 = $3,135,000). As you see in the earlier section “Dealing with fixed assets and depreciation,” there is no single method for calculating depreciation. So, the $685,000 is a combination of different depreciation methods. Some methods recognize depreciation evenly each year; others record more depreciation expense in the early years. For this chapter, assume that the $685,000 accumulated depreciation is a combination of different methods.

Tacking on owners’ equity

At this point, you've seen all the components that make up the total assets (refer to Figure 6-4). In the right column of the figure, you see two liability numbers — but no data for owners’ equity.

You can use the fundamental accounting equation to calculate total equity. As explained in Book I, Chapter 1, the fundamental accounting equation looks like this:

- Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ equity

- or

- Assets – Liabilities = Owners’ equity

Using the numbers from the balance sheet shown in Figure 6-4, you can calculate owners’ equity.

$3,855,000 assets – $515,000 liabilities = $3,340,000 owners’ equity

Completing the Balance Sheet with Debt

If you own Company X, whose balance sheet is depicted in Figure 6-4, how should you raise the $3,340,000 in capital? You can debate this question until the cows come home, because no answer is right or best. The two basic sources of business capital are interest-bearing debt and equity (more precisely, owners’ equity). Company management decides what percent of capital is raised by using debt, and how much from equity.

Going over the debt section of the balance sheet

Figure 6-5 presents the complete balance sheet for Company X, including its debt and owners’ equity accounts. These are the final pieces of the balance sheet puzzle (if you start at the beginning of this chapter, this is what you're working toward).

©John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 6-5: Complete balance sheet of Company X.

The business has borrowed $500,000 on short-term notes payable (due in one year or less) and $1,000,000 on long-term notes payable (due in more than one year). Interest rates and other relevant details of debt contracts are disclosed in the footnotes to the financial statements. For example, debt covenants (conditions prescribed by the debt contract) may limit the amount of cash dividends the business can pay to its shareowners. (See Book V, Chapter 4 for a discussion of footnotes.)

Tying in the new equity section

Note that Figure 6-5 displays a more detailed equity section than the simple equity total presented in Figure 6-4. The following sections describe the sources of these details.

Bringing up common stock

The shareowners in Company X invested $750,000, for which they received 10,000 shares of capital stock. Typically, a footnote is necessary to fully explain the ownership structure of a business corporation.

As a general rule, private business corporations don't have to disclose owners — the owners of their capital stock. In contrast, public business corporations are subject to many disclosure rules regarding the stock ownership, stock options, and other stock-based compensation benefits of their officers and top-level managers. Stroll over to Chapter 5 for more on equity topics.

Addressing retained earnings

Retained earnings represent the sum of all net income earned by the company since inception, less all dividends paid to shareholders since the business started. For more, head over to Chapter 2.

Over the years, the business in this scenario retained $1,090,000 of its yearly profits (see retained earnings in Figure 6-5). Two details aren't explained in the retained earnings line item:

- You can't determine how much of the cumulative total is from any single year's net income.

- Retained earnings don't reveal how much of the company's $255,125 profit for the year just ended (see Figure 6-2) was distributed as a cash dividend to shareowners during the year just ended.

One purpose of the statement of cash flows (explained in Book V, Chapter 2) is to report the cash dividends paid from net income to shareowners during the year.

Many businesses use debt for part of their capital needs. This practice makes sense as long as the business doesn't overextend its debt obligations.

Many businesses use debt for part of their capital needs. This practice makes sense as long as the business doesn't overextend its debt obligations.